B. Videira Pires, S.J.

(...)"the Portuguese is perhaps the least metaphysical and the most 'lyrical'character in Europe and, for that reason, the one which is, in terms of living experience, closer to the Chinese. We have seen that as far as popular proverbs and aphorisms are concerned. Lyrical Parnassianism and the bucolic love of Nature, the love for history, the rhythmic vitality of his art - a revenge of, or a compensation for the repressions of a very strict family system - the rural way of life considered an ideal by taoism, pacifism taken so far as to becoming indifference towards politics (a social attitude that is often necessary, because of the absence of legal protection and the egoism of the powerful), the simplicity of customs, frugality and sobriety as means of keeping physical and moral health, scepticism before the radical and revolutionary enthusiasm of unexperienced youth, traditionalism - those are other similarities between the Chinese and the Portuguese temperaments and human natures".

"In Canzusa (Katsusa), on the 14th June 1585", Father Luís Fróis, the Portuguese Jesuit, wrote and printed a "Tratado em que se contêm muito susinta e abreviadament algumas contradisões e diferenças de custumes antre a gente de Europa e esta provincia de Japão" [a Treaty in which are very succintly and briefly contained some contradictions and differences in the customs of the peoples of Europe and of this province of Japan], a book which was discovered, re-published and translated into German by Josef Franz Schütte, SJ, in 1955(1).

I would like to do the reverse in relation to Portugal and China, looking for the meeting-points of similitude and affinity between the two civilizations and preferably in relation to those which separate, divide, and possibly antagonize, us.

Only through such attitudes of open-mindedness, dialogue and good-will may we be able to reach an harmonious synthesis of understanding, esteem and sociability, a genuine form of universal cultural adaptation.

Tchak Seng Ló-Hón - the "star hunter"(Clay statuette by Sek Wan)

Tchak Seng Ló-Hón - the "star hunter"(Clay statuette by Sek Wan)

First of all, what is the real meaning of the term 'yellow race' with which, in a stereotyped and traditional manner, the Chinese are characterized in official identification documents (identity cards and passports) in history and geography books, etc.?

The first Portuguese who saw them and spoke to them described them as "white people", as much or even more than us (2). Let us expand the subject:

Huang-ti, or the Yellow Emperor, founded his capital in Yu Hsiung, in the Hsin Cheng district of the Honana Province, which is situated on the border of the 'loess' (yellow humus) area, a region from where the monarch's own name was derived. That district is, then, considered as the place of origin of the yellow tribe.

In the remotest antiquity, still bordering upon legend, China was divided into three spheres of political influence: the east, dominated by the T'ai tribe; the south, controlled by the Yen tribe; and the northwest, by the Yellow tribe. This last tribe, through their military and cultural achievements (among which we can count the old, old invention of written characters), transformed the other tribes and races into a great nation.

'Yellow race' is, then, derived from the colour of the territory which was the cradle of the Chinese civilization properly speaking and which included the margins of the Yellow River (Huang Hó). The reference does not spring from the actual colour of the skin of its inhabitants. The white race cannot, therefore, be opposed to the so-called 'yellow race' on the grounds of their skin colour. (3)

The term 'race' cannot, in fact, be accurately defined, being only applicable to such tremendous generalizations as 'black', 'white', 'yellow', and 'red'. The concept of a "pure race", with fixed elements of structure and pigmentation has been refuted for a long time.

Excluding the Northern Europeans, the Chinese, the Japanese and the Koreans do in fact have a lighter epidermis than the so-called 'whites', especially the Portuguese. That feature, then, does not differentiate, and even less divide, us. The somatic features of mongoloid origin are more of a yellow or tanned type than those of Indo-European or Germanic origin, but the original Han type, which is even nowadays predominant in most Chinese provinces, is white.

Three cocks among peonies and marigolds-Dish of the Kien Lông period

Three cocks among peonies and marigolds-Dish of the Kien Lông period

And, in fact, at a higher level of analysis, 'race' as representing the continuity of a physical type is equivalent to a natural group which can have noting in common, and generally does not, with people, nationality, language and customs, all notions which correspond to purely artificial groups, devoid of anthropological bounds, and justified only by the history of which they are but the products. There is, then, no British race, but a British people; no French race, but a French nation; no Arian race, but Arian languages; no Latin race, but a Latin civilization.. And there is no Chinese race, we might add, but a Chinese civilization. (4)

Mind cannot be sacrificed to matter, nor psychic values to the determinism of biological factors, nor even animal phenomena (like race) to that which is specifically human: culture. The key to the problem of civilization is not biology, but history.

It is in popular sayings and aphorisms that the enlightened humanism (wisdom) and the moral quality of a people are best revealed. The late Chanter of the Cathedral Church of Macau, António André Ngan, demonstrated in an extremely good collection of texts, the ideological and often even metaphorical agreement between most of the Portuguese and the Chinese popular sayings. The importance of this discovery will never be too much emphasized. (5)

"(Portuguese proverbs and aphorisms) show a striking coincidence with those of China. There is only one pitagoric-budhist element wich the Portuguese ones do not include: the transmigration of Foulds".

In fact, "wisdom or sapience is the perfection of knowledge, which consists in the understanding of both divine truth and of the others which are dependent upon it." (St. Thomas Aquinus). In other words, sapience is the practical consciousness of the primacy of moral and spiritual values and the living experience of the total meaning of life. For man, as all created beings, can only be understood in his relation to the Absolute. That is what the Japanese call "amaeru", i.e., the radical sensation of being able to communicate with 'another', being loved and enjoy living under the dependence of the love of one's mother, family, society and, finally, God, our Father, "from whom all perfect gifts come". And God's action is an eternal present.

In the history of the concept of knowledge, some specific aspects are progressively emphasized, such as the technical aspect of 'savoir-faire', or ability, the theoretical (which, according to Pitagoras, corresponds to philosophy), the theoretical-practical (Aristotle and the Indian Vedas), the moral (Stoicism, Egypt, Babylon, Descartes, Leibnitz, Spinoza, Kant and Hegel) and the religious (Filon, Plotinus and Kierkegaard). The most usual literary expressions of the practical 'side' (moral value and common sense) of the term "wisdom" have always, and among almost all peoples, been proverbs and aphorisms (sometimes in their longer versions - 'apologues') of which the Portuguese, as we have already mentioned, show a striking coincidence with those of China. There is only one pitagoric-budhist element which the Portuguese ones do not include: the transmigration of souls.

Keyserling tried to harmonize the Eastern and the Western traditions of the notion of knowledge, criticizing the exaggerations of the Western techno-intelectualist culture in which the sense of life's totality is almost completely lost. He has, however fallen into the mistake of attributing knowledge to magic and to teosophism, which are but degenerated or corrupted forms of it.

A ccording to modern psychology, the Western way of life and of thinking is based upon psychic reality, i.e., pasyche as the main and the only condition of existence, which is considered more as a psychological and temperamental sort of fact than a result of philosophical reasoning. That is an introverted point of view or state of consciousness.

Introversion and extroversion are, in fact, temperamental attitudes or even attitudes dependent on individual constitution and which are never intentionally adopted in normal circumstances.

Well then, introversion "is the style of the East". Freud thought, therefore, that it went against communitarian feeling and the philosophy of National Socialism and so condemned it. We know, however, that the notion of the superiority of the Arian-German race is an aprioristic myth. On the other hand, Schopenhauer's pessimism - founded upon a false reading of Budhism - is one of the 'deformities' of that psychological type (the predominance of the 'anima' or feminine element).

Nevertheless, the introverted mind has a great power of self-liberation. It easily forgets aggravation and is able to sleep better after depressing moments.

There are states of mind which transcend consciousness, but there are no conscious states which do not refer to a subject (a self). Only by indirect means (dreams, hypnosis, etc.) does the self become aware of the movements of the unconscious. That compensation of the unconscious is situated, as we have said, beyond man's normal control.

The mind of the East is not as egocentric as the mind of the East.

The Eastern culture tends to be existential, with no artificial or abstract divisions. Poetry, painting, the tea ceremony of the Zen budhist school, flower arrangements, miniature plants, respiratory gymnastics, martial arts (kông-fu), etc., all insist on the vertical attitude of the mind (the penetration of the object, the union with it, the oblivion of self, the attention to neither the past nor the future, but to the present moment only). The Western thought on the contrary, before Existentialism and the philosophy of the real (Kierkegaard, Gabriel Marcel, and others) was generally concerned with the essential and silogistic being and tended to underestimate intuition and mysticism.

Those two points of view, although opposed (or in opposite poles: positive and negative) have, each of them, their own justification. They are both unilateral and tend not to take facts which do not fit thier attitude into account. The East underestimates the world of reflexive consciousness, the West, the world of the Super-ego (the Universal mind, the collective sub-conscious). The result is that each of them - East and West-in their extremism loses half of Man and half of the Universe. The unconscious belongs to us, too, and it constitutes a formidable reserve of life.

In the West, there is the 'mania' of objectivity, of "clear, distinct ideas" as in Descartes, the Greek dualisms (form and matter, mind and body, natural and supernatural, essence and existence, etc.) of the scientist and the stock-dealer's asceticism, throwing away or at least hurrying over the beauty and the universality of life, in a sort of blind love for their ideal or, should one say, their instinct. The East does not 'dichotomize' reality, it does not create the "ens rationis".

"The East underestimates the world of reflexive consciousness, the West, the world of the Super-ego (the Universal mind, the collective sub-conscious). The result is that each of them - East and West - in their extremism loses half of Man and half of the Universe".

In the East, there is Wisdom, peace, unattachment, non-action (which are a force or the spring of all energy, for they are concentration, resistance, inertia, the accumulating dam). (6)

The two modes of thought (intuitive and discursive) are important and each of them can gain from the union of the horizontal and the vertical so as to integrate a future-world culture. The two tendencies of the Western and the Eastern soul have a magnificent common purpose: both make desperate efforts, using different ways and different means, to conquer the genuine naturalness of life.

In a word, China is more feminine and intuitive and Europe more masculine and metaphysical. If they unite, they can make each other whole.

"The East prefers immobility as the form of the infinite: the West prefers movement. For the latter has a passion for detail and the vanity of the individual, of the multiple. (...) Another of the services which Christianity renders us is this eastern element in our culture. It serves as a counterweight to our tendencies to the finite, the transient, the instable, concentrating the mind through the contemplation of eternal things - platonizing a little our affections, which are constantly deviated from the ideal world, leading us from dispersion to concentration, from worldliness to retirement - bringing calm, graveness, noble-mindedness back to our souls made febril by petty narrow desires." (7)

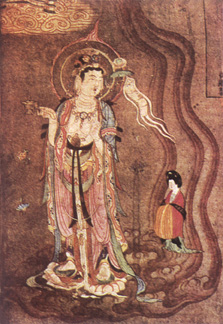

The feminine representation of the same Buddha - Song Dynasty.

The feminine representation of the same Buddha - Song Dynasty.

The qualities of feminine intelligence and logic - Lin Yutang wrote - are those of Chinese mentality: common sense, or intuition, and an horror of abstract terms. In fact, the Chinese mode of writing and of thinking is simple, concrete in its images, practical and it reveals itself especially in proverbs and metaphorical expressions, as it happens in women's conversations in general. The Chinese personify logic and science, they make Law an art. They do not take to superior mathematics and have never developed logics as a science nor grammar in speech and writing. Their mathematics and astronomy were, to a great extent, imported from the Moslems in the Middle Ages and, after the seventeeth century, from the Europeans. (8)

The Chinese derive enormous pleasure from ethical and sapiential concepts, creating a sensation of bashfulness and superficiality, and also from concrete terms. That is why they are naturally vague in their discussions, merely skimming over their subjects.

They hate scientific treatises, because their intelligence is essentially analytical. They have not developed a science as such, based on the relative immutability of the laws of Nature and on the consequent axiomatic principle of causality. China has recognized, maybe intuitivelly, that natural law is composed of static truths, but not of absolute truths - and they necessarily admit exceptions. The West is now also able to admit the unforeseen in its calculations, thus escaping dogmatism.

The Chinese avoids defining the essence of things, partly because he lacks the verb 'ser' [T. N.: a translation of 'ser' as 'to be' would not be exact, for the Portuguese language has two different verbs which correspond to it: 'ser', a more 'essential' reference, and 'estar', a more 'accidental' form of being.]. He does not distinguish between accident (attribute) and substance. He even admits that 'existential' truth cannot be proven, it can only be felt through intuitive perception (Chuangtsé). It is clear that our perception of truth in the world is not ever absolute, it is necessarily partial.

"The two modes of thought (intuitive and discursive) are important and each of them can gain from the union of the horizontal and the vertical so as to integrate a future-world culture. In a word, China is more feminine and intuitive and Europe more masculine and metaphysical. If they unite, they can make each other whole".

Continually experiencing this fact in every area, the Chinese is not so much worried about the definition of "what this is" (the mystery of being touches everything), but instead he wants to know, as far as it may be possible, "how this is". He leaves the distinction between substance and attribute or accident aside; that distinction was, by the way, imported by Budhist thought by means of its discussions. There is among the Chinese no epistemology, no criticism of knowledge. They concentrate their faculties of knowledge (common sense, or intuition, and pragmatism, especially) upon man's actions and matters and not on the problems of Nature and the Universe as such. Reasoning and cold deduction, the meticulous induction of the Germans, do not interest them.

Avalokiteçvara showing the way. (Painting on silk by Touen - houang - London, British Museum, Stein Collection, Tang Dynasty)

As we refer this difference - which is not a difference of constitution but a psychological - function between the Chinese and the westerner, we must note that the Portuguese is perhaps the least metaphysical and the most 'lyrical' character in Europe and, for that reason, the one which is, in terms of living experience, closer to the Chinese. We have seen that as far as popular proverbs and aphorisms are concerned. Lyrical Parnassianism and the bucolic love of Nature, the love for history, the rhythmic vitality of his art - a revenge of, or a compensation for the repressions of a very strict family system - the rural way of life considered an ideal by taoism, pacifism taken so far as to becoming indifference towards politics (a social attitude that is often necessary, because of the absence of legal protection and the egoism of the powerful), the simplicity of customs, frugality and sobriety as means of keeping physical and moral health, scepticism before the radical and revolutionary enthusiasm of unexperienced youth, traditionalism - those are other similarities between the Chinese and the Portuguese temperaments and human natures.

Confucius once said to a disciple of his: "the same and single thread runs throughout my doctrine". He meant to say that all men share the same mentality that penetrates all things, like the same blood feeds all the cells in the body. We, westerners, continually face the same problem as the Chinese: that of reconcilling our primitive and individual self with the external, social and conventional self. Within the same human nature which we all possess, we are as much Chinese as they are. Deep down, our struggles are their struggles, our longings and our conquests, their longings and their conquests. It is easy to exaggerate or to undervalue our differences. The average term, or golden rule, (a combination of prudence and temperance) is a cardinal virtue both for the Confucionist and for the Christian ethics. Is not "Chông-Yông" (average) a classic in China, and perhaps the key and the summula of all the others? (9)

"Two other features of the Chinese character which are close to the Portuguese are fanciful idealism and the negligence or carelessness as far as 'finishing touches' are concerned. This tendency to indolence leads to the absence of dialectics and of a scientific method, to the lack of planification, to improvisation - which are also Portuguese faults. The Chinese is too prone to believing in the impulses of his common sense and intuition".

The love of Nature, the ideal of country life are a permanent presence in the Chinese and in the Portuguese art. The contemplative and involving relationship of the Chinese with Nature and Nature as a state of the soul are well illustrated in these two paintings (a painting by Chóu Ying of the Ming Dynasty; "The Appletree" by Sousa Pinto in Museu Soares dos Reis)

Two other features of the Chinese character which are close to the Portuguese are fanciful idealism and the negligence or carelessness as far as 'finishing touches' are concerned. To illustrate this double similarity, it will be enough to think of the Chinese novels of the eighteenth century (the period of Emperor K'ien Lung), the arhat or budisava "Star-Catcher" (Tchack Seng-Ló-Hón) the old Chong K'uai folk tale (Attracting hapiness, symbolized in a bat, home) and the modern Wu Sek (or Hsi) novel, Mr. More or Less (Chá Pat Tó Sing-Sang). (10)

This tendency to indolence leads to the absence of dialectics and of a scientific method, to the lack of planification, to improvisation - which are also Portuguese faults. The Chinese is too prone to believing in the impulses of his common sense and intuition.

"The Chinese also lacks a patriotic and a nationalist sense and abounds in individualism. And, by the way, the term and general concept of 'society' (sé wui) was introduced in China only about eighty years ago".

The Greeks launched the foundations of science, because their intelligence was specifically analytical. Analysis demands a special attention to detail, hard work and perseverance. The Chinese, on the contrary, did neither develop abstract thought, nor did they possess the awareness of universal ideas. They over-emphasize their perception of the concrete or of the whole reality (essence and existence) and they derive much pleasure from the practical form of complex multiplicity. Thence their love of nature, which is taken as far as that which we call Pantheism, or an exaggerated emphasis upon the immanence of God. Thence also their esteem for hierarchy and history and their tendency for the reconcilliation, sometimes even in paradoxical terms, of opposites.

The Far East is, in fact, the land of social compromise and of religious sincretism. The Chinese also lacks a patriotic and a nationalist sense and abounds in individualism. And, by the way, the term and general concept of 'society' (sé wui) was introduced in China only about eighty years ago. (11)

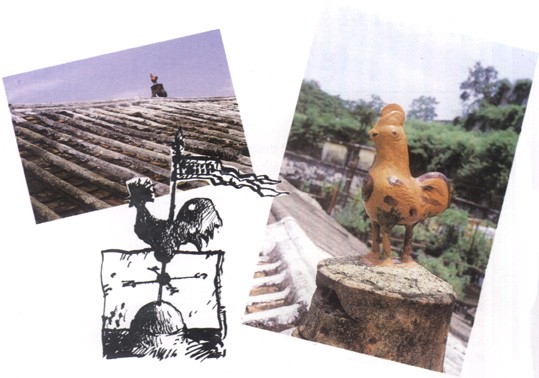

To conclude this analysis, we should also refer, in the area of symbology and folklore, the cock's crow, during the night and at dawn, which is yet another parallelism between the lusiad and the Chinese cultures.

As a matter of fact, the 'galo de Barcelos' (cock of Barcelos) represents, in the tourist register, our country. I recall - and I miss - the 'festa do galo' (cock party) which we, the graduating students of the Torre de Da Chama Primary School, organized. I evoke the cock fights in Indonesia, the Marianas, and in Macau - and also the Chuang Tzu legend of the "unperturbed cock".(12).

The cock is, both in the West and in the East, a herald of the sun, not only because of his merry songs which stab the night, but also because of his crest, of his fiery crown. The cock is a devil-dispeller, for he calls for daylight which draws nearer and nearer scaring away the 'evil spirits' which haunt the night. A Catholic liturgical hymn agrees with this interpretation: the cock's crow makes Peter, the Apostle, aware of his (and our) sins of the denial of Christ (13). In Portugal, the weathercock upon so many church roofs reminds the churchgoers of the importance of prayer in order to avoid temptation. Several 'quadras populares' [T. N: a popular form of four-line stanza] also refer the cock as both watcher and prophet. Both the Greeks and the Romans used cocks for decipherating their presages which, they hoped, would spell out victory. France, with its 'calembours', maybe playing with the words Galia and galo, adopted the bird as a national emblem.

A cock's statuet, upon the old roofs of Macau, protects the house against the white ants which feed on wood, under the dark blanket of the little sawdust tunnel in which they penetrate and work.

"A cock's crow suggests to me mirages of a world of delights, country alacrities, village glee, a quiet family life, with a wife and many children... I must have had a remote ancestor who never saw the sea, who never dreamt of travelling or of exotic places, content with tilling his land, with listening to his ox bellowing, his watch-dogs barking, his cock's crowing, and out all of the rustic orchestra of a plain life, a pleasure for my old and unknown relative, the love for the cock-crow at dawn has, perhaps, remained in me." (14)

The bucolic quality of the cock-crow is part of the taoist ideal which was so imperative to Chinese art and philosophy. I quote Lao Tsu's "Tao Te Ching", according to the already-mentioned translation: "A small village has few inhabitants... they are happy in their way of life. Although they live within the sight of all their neighbours, and the cocks's crows and the dogs' barks may be heard all over, they bear one another in peace, as they grow old and die." (15). We could almost visualize Macau and Ch'in Shán, on the other side of the 'Portas do Cerco', from 1557 to the beginning of the First World War with the flood of countless refugees who sought shelter here.

The big village of 'Ou-Mun-Kai' (Macau street) - as the Cantonese used to call this city forty years ago, became (for better or for worse?) a miniature of Manhattan. The building fever and the destructive hammer of material progress - devoid of a total unity - have made the small-farms, the green-gardens, the backyards vanish with their fig-trees, their vines, and their pomegranate-trees, where the cry of those night--watchers came from.•

Bell tower cock (drawing) and cocks on the old roofs of Macau; the herald, vigilant cock dispelling evil spirits and the dangers of the white ant.

NOTES

(1) Luís Fróis, SJ KULTUR GEGENSATZ EUROPA-JAPAN (1585), Tokyo, Sophia Universität, 1955.

(2) Cf Letter by Father Manuel Teixeira, SJ. of the 10th December 1565, in Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau, Vol. 62, Out. e Nov., pp. 787-788.

(3) Cf Chang Chi-yun, Chinese History of Fifty Centuries, transl. by Chu Li-hen, Taipeh, 1962, Vol. 1.

(4) Cf M. Boule, Les hommes fossiles, p. 320. Cf E. Pittard, Les Races de l'historie. Introduction ethnologique à l'Histoire. Paris, 1924.

(5) Chantre, António André Ngan Concordância Sino-Portuguesa de Provérbios e Frases Idiomáticas, Macau, 1973.

(6) Joseph Cambell, The Portable Jung, Penguin Books, 1977, pp. 178-269, 480-502. William Johnston, The Still Point, reflections on Zen and Christian Mysticism, Fordham Univ. Press, N. Y., 2nd printing, 1980, pp. 98-99, 119 and following. Lao Tsu Tao Te Ching, a new transl. by Gia-Fu Feng and Jane English, N. Y., 2nd ed., 1982, poems number 8, 10, 16, 22, 37, 42, 43, 45, 47, 56 (spontaneity, naturality of taoist non-action is the constant element in Lauciu's mysticism.).

(7) Cf Henri-Frédéric AMIEL, Diário Íntimo, Vol. I, Porto, 1944, Liv. Tavares Martins, pp. 171-173.

(8) Cf Lin Yutang, My country and my people, 10th printing, pp. 85-88

(9) Ben-Ami Scharfstein, The Mind of China, Basic Books, N. Y., pp. 4, 29,134-139. Fung Yu-lan, A History of Chinese Philosophy, transl. by Derk Bodde, Princeton, 1953 (2 vols.). Hagime Nakamura, Ways of thinking of the Oriental Peoples, Honolulu, 1974, pp. 380-500.

(10) Transl. into Portuguese by A. Teixeira, in "Jornal de Macau", 15 Dez 1982, p.3.

(11) Hajime Nakamura, op. cit., pp. 175-294

(12) Reproduced in "O Clarim", Macau, 12 Dez., 1983, p.8

(13) The 'officium lectionis' hymn, Friday c. t. (the Liturgy of the Hours).

(14) Cf Wenceslau de Morais, Ó Yoné e Ko-Haru, ed. "A Renascença Portuguesa", Porto, 1923, p. 254.

(15) Cf Lao Tsu, Tao Te Ching (same transl.), 80th poem.

start p. 14

end p.