A lifetime, these now sixteen years in Macau. And it feels as though I had arrived only yesterday! How different the "before" and the "after" of this period of time, so rich in living experience, so surprising to my European eyes.

The first contacts were of confusion and strangeness: a multitude of faces, a different language, different behaviour, and even the warm, damp atmosphere of that late May, all of it seemed to strike the 24 years of 'portugueseness' I had brought with me. I intimately though: I'm going to make a fast retreat - how can I ever stand life here for two long years?!" We were in 1970!

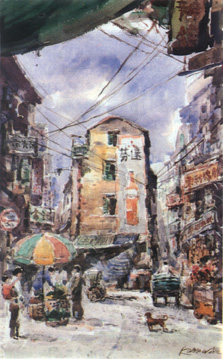

That which was, which has been being, destroyed, was both typically Portuguese and typically Chinese. We had a city which was worthwile seeing, visiting. We now have a city devoid of almost its entire picturesqueness, despoiled of its attractions, uncharacteristic, shapeless. (...)". And he was certainly right, one has only to look at old pictures to believe he was. But there was yet enough matter left for my delight when I arrived here. The pupils, my companions in this adventure, would ask questions as if they were looking at all those things for the very first time, in spite of the fact that many of them had been born and raised right here in Macau. They usually walked three or four of the main streets and had never before noticed how the houses had an upper floor, nice friezes upon the windows and the balconies, roofs with artistic and copious ornaments.

</p>

<p>

The overall tone of the old houses, of an ochre-yellow, seemed to diffuse itself in a sort of golden powder when the evening sun obliquely caressed the narrowest alleys, just before the evening shadows settled upon them.

</p>

<p>

The magic gradually took possession of ourselves: the Lilau, with its spring of spell-casting water - he who drinks it shall forever be bound to Macau! - the calm rhythm of façades all over the city, outlining residential quarters, well aired and protected from the excessive sunlight by the neat sequence of window-blinds; the Portuguese-looking paved street; the surprise of a community well whereto little streets with naive names written on tiles in the corners would converge: Handkerchief and Fan alleys Dissimulation and Eternal Happiness courtyards, Tea-Pot and Hook lanes, Ivory and Ambassador causeways, Fire-wood Boat Street!

</p>

<p>

<B>A</B>unique "book" on world diplomacy, daily written by the man-on-the-street not with words, but with events, Macau represents the most fecund example of that which can be considered, in the Portuguese world, a spontaneous complementarity of values.

</p>

<p>

But why, teacher? Why the names, why all of it? Why?

</p>

<p>

Oh, how grateful I am for all those <I>Why) They made me obey, pay attention, learn! For the love of my pupils I began loving Macau, wanting to know more about its people, its history, a delicate, flexible web which has resisted the not always easy dialogue between the East and the West. A unique "book" on world diplomacy, daily written by the man-on-the-street not with words, but with events, Macau represents the most fecund example of that which can be considered, in the Portuguese world, a spontaneous complementarity of values.

They made me obey, pay attention, learn! For the love of my pupils I began loving Macau, wanting to know more about its people, its history, a delicate, flexible web which has resisted the not always easy dialogue between the East and the West. A unique "book" on world diplomacy, daily written by the man-on-the-street not with words, but with events, Macau represents the most fecund example of that which can be considered, in the Portuguese world, a spontaneous complementarity of values.

Armando Martins Janeira states his belief in the balance which Eastern serenity can bring to Western restlessness for the benefit of general peace, if the emphasis is given not to the politics of power but to cultural solidarity.

As far as this question is concerned, I have my own opinion. I think that experience presuposes the identity of both, and that is the safest way of reaching the truth of things.

Considering all I have been able to gather up to this day, I may say that I can discover the benefits which the dialogue I have been establishing between me and myself in Macau has transmitted to my life: what I was, what I keep, what I have rejected, what I have acquired, what I am. Today, I value everything that surrounds us, for it will remain and speak of us, as a collective body, much more than I do the social, transient emergences of our personal lives. I can now fight anxiety and conquer peace of mind, as though in a cell inside of me. I have become used to waiting, with silent stunbborness and a smile on my lips, although I often forget this acquired behaviour and let myself plunge into my Latin roots in the most unexpected manner!

I got used to the idea that there are natures which are completely different from ours, capable of unknown, surprising reactions, in endless sequence and combination. The Chinese people are permanently unforese eable. Living side by side with them is fascinating. But one must know how to! How often, during all these years, have a sought a resting-place near Grandfather where I could get away from this "diplomatic exercise"! He had been a diplomat in China himself and now lived in an old quarter tucked up among enormous trees, and possessed the best living memory in town. Many used to come to him just for the pleasure of listening to the reminiscences which his tired, trembling hand could no longer register. But his voice, his liveliness, the fine irony which his lips so often silenced but his eyes could not hide, were reasons enough for a worthwhile visit.

I would always wait until the evening to meet him, when the breeze would be coolinng the ample arcades in the balcony.

There were several rituals to be performed at that hour: take the bird's cage inside, water the plants, order a lemonade, avoid disturbing thr swallows which were building their nests in the light globe. And, by the way, that light was seldom used at all. The pleasure of nightfall was deliberately prolonged, when the inebriant symphony of lights and perfumes became stronger as the warm night was being born.

Today, I value everything that surrounds us, for it will remain and speak of us, as a collective body, much more than I do the social, transient emergences of our personal lives.

The straw chairs would squeak and Grandfather, lost in his contemplation, broke the silence as one who is just wrapping off a thought:

..."in those days..."

Bound to it, almost as wonderfully and almost as simply as I used to be in my childhood when someone started the telling with "Once upon a time...", there I would be absorbing all his words, his power of evocation so expressive that the scenes described seemed to become alive in the telling. The barkings of 'Tejo', the dog, playing with my sons in the garden, would only vaguely reach us. In the dining room, nibbling watermelon kernels, the rest of the family waited for dinner to be served. And in those brief moments, the two of us in the balcony, oh, the memories! The city would gain a soul of its own and I started to understand it and love it more and more:

"The big house at the bend that leads to the Hill, hidden behind camellias and magnolias... - Grandfather would tell - there lived an old friend of mine... you know... hum... well, So and So is his granddson... his mother was a very beautiful day... his father, a most distinguished officer... he killed himself, well, it's a very sad story..."

And I, as in the poems of Lopes Vieira on Schumann's Childhood Scenes, insisted: "Tell me... tell me... tell me!"

Meakly led by the telling, my imagination made scenes as were never seen and others which can only seldom be, materialize: the time of jinrikishas, the 'coolies' with their long pigtails, the peddlers offering hot buttered buns to groups of children on their way to school, 'achares' of papaya and sweet-and-sour turnip arranged in bamboo sticks, freshly made caramel candies, noodles and fritters, and also the chicken broth, hoarsely announced from door to door in a centennial street cry.

Alongsidde with such small delights, there was the other side of life: epidemics, promiscuity, the self--denial of a certain doctor, the reluctance against vaccination, the visits and the assistance provided by the self-forgetful missionaries running a permanent risk of infection, the pain and the desolation with which death had marked such times - of all of it Grandfather would tell.

And I started to feel that after such vivid 'watercolours', I needed to search out documents and fundament all the news on a more solid basis.

Designer by Ung Wai Meng © Copyright

The history of Macau, aroused in me by the wonder of it, as in Wagner's operas, has screated the necessity for a scientific approach. I was soon appointed the director of the Historical Archives, and found myself surrounded by pages and pages of Past which seemed to be looking at me like a challange. To have accepted and to have done that work was one of the nicest things in my life. I started to feel Macau differently, to respect its phisical outline, its cut sillouette, the green patches which are like a pedestal to the Guia lighthouse. And I started to understand, by the confrontation of documents and reality, the strategy of the fortresses, the urban irradiation around convents and churches, just like in the old medieval European towns.

Macau seemed to become more and more familiar to me with each passing day, revealing itself as a little nook with a soul of its own, a big soul such as the Portuguese possess, open kto both the Eastern and the Western minds, welcoming, with a charm like the one which once threatened Ulysses, soothing his homesickness. Or was it that the water I had drunk at the spring of Lilau was starting to have an effect upon me?

Will I be able to explain this very complex and unexpected love for a land which has nothing in common with my roots in Coimbra, the harbour of my youth, which I had left, breaking off the chains of illusion in a 'Should I go? Should I stay?' dilemma eventually solved by the altantic side of myself in an clear option for adventure?

For me, Macau was and will forever be that which I have kept inside my heart. I am glad that the mark is there, indelible, when I close my eyes. Because - when I open

Tears come to my eyes and, for a moment, I think that I fail to see it on account of my emotion. But, also! So many things have been, and are, disappearing, swept by the machines which today's man calls the progress of this century!

Such an involving atmosphere was the one in which the 'children of the place' were raised, giving them an intuitive existential sequence which has disappeared in the name of often standardized and impoverishing 'vanguardisms'!

When, in the future, we want to talk about, and prove, our four-century old presence in China, will it be necessary for us to turn old pages and watch 'slides' with images of what was, having effaced the marks we had left here, as though it could make the retreat any easier?

And a problem of identity faces the people of Macau, who, when they look around, can no longer recongnize their own hometown. And, which is even worse, who let themselves be deceived by hypothetical advantages of comfort from which they believe they can derive some benefits when, in the long run, they shall end up by losing them. It will not take too long before a psychological crisis arises, born out of the lack of living space, in the behive-like buildings which are exhausting, where noise is multiplied, where no one knows, let alone help, anyone. Children want an ample space in which to grow up but in order to have it they have to go out of their homes, where their growing process should be taking place and love should be prodigalized, and resort to public gardens, often by themselves, risking so many dangers! Parents and children will soon be better acquainted with anxiety - and they are already beginning to be than with harmony.

In Macau, where the islands are a yet-unexplored outlet, Macau, which has up to this day been proud of the balance of its population, is letting itself be swept by unhealthy winds. Countless voices have lately been heard both in the press and in our daily conversations, here and there, claiming against the destruction of the city's most typical features. The case is -it is absolutely necessary to avoid, at all costs, late and useless comments such as "it was a real pity, in fact" My house, a solid 40 year old building, has got a rustic little eaves edge over the front door, somewhat in the Raul Lino style. On the stone pillar which helps define the entrance, the name of the constructor, Sin Chung Kwan, is carved. The house is, therefore, a 'signed' piece. But that fact is of no use at all to it: it has been sold and will be replaced by a block with several storeys. My Grandfather's house, along with the residential quarter I have known in full exhuberance, is now a bare, dry area where the foundations are being laid for a car--parking site by means of a deafening pounding hammer which produces earthquakes in the whole neighbourhood!

As withnesses for our old patrimony, we have countless exhibition catalogues and photographic albums which do keep images of "paradise lost". When, in the future, we want to talk about, and prove, our four-century old presence in China, will it be necessary for us to turn old pages and watch 'slides' with images of what was, having effaced the marks we had left here, as though it could make the retreat any easier?

From this room where I am writing from inside these walls which I know will be pulled down, I feel something collapse farther away, as if in a Dante--inspired dream: the staircases, the roof eaves, the old palace in the corner of the garden, all among a growing, dense powder which the dying sun paints in gold.

No, I do not want to open my eyes, hoping that poetry may help me overcome this moment.

Again, Manuel Bandeira:

"They're pulling this house down

But my room will remain

Not as an imperfect form in this world

of appearances:

It will remain in eternity

With its books, with its pictures, intact,

suspended in the air!"•