Designer by Yuan Zhi Qing © Copyright

Designer by Yuan Zhi Qing © Copyright

Dayanhe, my wet-nurse:

Her name was the name of the village which gave her birth;

She was a child-bride:

My wet-nurse, Dayanhe.

I am the son of a landlord,

But I have been brought up on Dayanhe's milk:

The son of Dayanhe.

Raising me Dayanhe raised her own family;

I am one who was raised on your milk,

Oh Dayanhe, my wet-nurse.

Dayanhe, today, looking at the snow falling makes me think of you:

Your grass-covered, snow-laden grave,

The withered weeds on the tiled eaves of your shut-up house,

Your garden-plot, ten-foot square, and mortgaged,

Your stone seat just outside the gate, overgrown with moss,

Dayanhe, today, looking at the snow falling makes me think of you.

With your great big hands, you cradled me to your breast, soothing me;

After you had stoked the fire in the oven,

After you had brushed off the coal-ashes from your apron,

After you had tasted for yourself whether the rice was cooked,

After you had set the bowls of black soybeans on the black table,

After you had mended your sons' clothes, torn by thorns on the mountain ridge,

After you had bandaged the hand of your little son, nicked with a cleaver,

After you had squeezed to death, one by one, the lice on your children's shirts,

After you had collected the first egg of the day,

With your great big hands, you cradled me to your breast, soothing me.

I am the son of a landlord,

After I had taken all the milk you had to offer,

I was taken back to my home by the parents who gave me birth.

Ah, Dayanhe, why are you crying?

I was a newcomer to the parents who gave me birth!

I touched the red-lacquered, floral-carved furniture,

I touched the ornate brocade on my parents' bed,

I looked dumbly at the "Bless This House" sign above the door-which

I couldn't read,

I touched the buttons of my new clothes, made of silk and mother-of-pearl,

I saw in my mother's arms a sister whom I scarcely knew,

I sat on a lacquered stool with a small brazier set underneath,

I ate white rice which had been milled three times.

Still,

I was bashful and shy! Because I,

I was a newcomer to the parents who gave me birth.

Dayanhe, in order to survive,

After her milk had run dry,

She began to put those arms, arms that had cradled me, to work,

Smiling, she washed our clothes,

Smiling, she carried the vegetables, and rinsed them in the icy pond by the village,

Smiling, she sliced the turnips frozen through and through,

Smiling, she stired the swill in the pigs' trough,

Smiling, she fanned the flames under the stove with the broiling meat,

Smiling, she carried the baling baskets of beans and grain to the open square where they baked in the sun,

Dayanhe, in order to survive,

After the milk in her had run dry,

She put those arms, arms that had cradled me, to work.

Dayanhe was so devoted to her foster-child, whom she suckled;

At New Year's, she'd busy herself cutting winter-rice candy for him,

For him, who would steal off to her house by the village,

For him, who would walk up to her and call her "Mama",

Dayanhe, she would stick his drawing of Guan Yu, the war god, bright green and bright red, on the wall by the stove,

Dayanhe, how she would boast and brag to her neighbors about her foster-child.

Dayanhe, once she dreamt a dream she could tell no one,

In her dream, she was drinking a wedding toast to her foster-child,

Sitting in a resplendent hall bedecked with silk,

And the beautiful young bride called her affectionately, "Mother."

…………………………

Dayanhe, she was so devoted to her foster-child!

Dayanhe, in a dream from which she has not awakened, has died.

When she died, her foster-child was not at her side,

When she died, the husband who often beat her shed tears for her.

Her five sons each cried bitter tears,

When she died, feebly, she called out the name of her foster-child,

Dayanhe is dead:

When she died, her foster-child was not at her side.

Dayanhe, she went with tears in her eyes!

Along with forty-nine years, a lifetime of humiliation at the hands of the world,

Along with the innumerable sufferings of a slave,

Along with a two-bit casket and some bundles of rice-straw,

Along with a plot of ground to bury a casket in a few square feet,

Along with a handful of ashes, from paper money burned,

Dayanhe, she went with tears in her eyes.

But these are the things that Dayanhe did not know:

That her drunkard husband is dead,

That her eldest son became a bandit,

That her second died in the smoke of war,

That her third, her fourth, her fifth,

Live on, vilified by their teachers and their landlords,

And I - I write condemnations of this unjust world.

When I, after drifting about for a long time, went home

On the mountain ridge, in the wilds,

When I saw my brothers, we were closer than we were 6 or 7 years ago,

This, this is what you, Dayanhe, calmly sleeping in repose,

This is what you do not know!

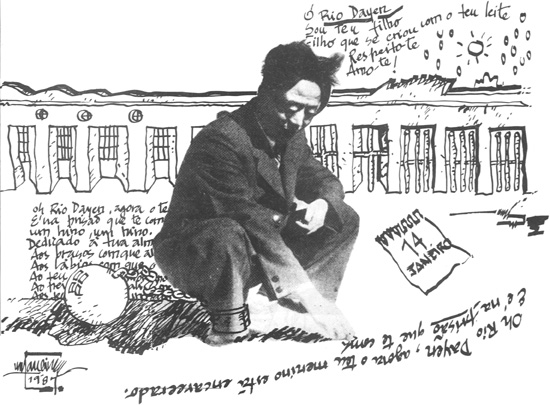

Dayanhe, today, your foster-child is in jail,

Writing a poem of praise, dedicated to you,

Dedicated to your spirit, purple shade under the brown soil,

Dedicated to your outstretched arms that embraced me,

Dedicated to your lips that kissed me,

Dedicated to your face, warm and soft, the color of earth,

Dedicated to your breasts that suckled me,

Dedicated to your sons, my brothers,

Dedicated to all of them on earth,

The wet-nurses like my Dayanhe, and all their sons,

Dedicated to Dayanhe, who loved me as she loved her own sons.

Dayanhe,

I am one who grew up suckling at your breasts,

Your son.

I pay tribute to you,

With all my love.

On a snowy morning, January 14, 1933

(Translated by Eugene Chen Eoyang)

Illustrations by Carlos Marreiros~&C Copyright

start p. 58

end p.