With this title, my intention was to express what has now become a global issue for the development of art in the twentieth century: the differentiation and assimilation of Eastern and Western cultures. Whether from a historical or comparative perspective, this movement has already become the most significant cultural phenomenon confronting the contemporary art world of today.

The term "Neo-Orientalism" first originated during a visit paid to me in the late 1980s by the art critic and poet Huang Xiaofeng. 1 During the visit, I was asked whether I could define my artistic aims, ideas and techniques in a few, brief words. My response to this was to confess that I was confronted with a dilemma as to whether my art should be governed by historic or more personal considerations.

During the 1950s, the abstract form dominated the international art world. Artists emphasized what is termed 'poetic abstraction'; the traces left by gesture and speed. These traces were sometimes associated with Chinese calligraphy. A few examples of work suggesting a certain 'orientalism' started to appear at that time by artists such as Mark Tobey and Hyrlogink, both of whom had studied Chinese calligraphy in Asia. Despite a seeming oriental connection, however, the work they produced was thoroughly Western in conception. In the 1960s, Dadaism, which had originated a few decades before other art movements concerned with the connection between time and space and sensory experimentation, — Happenings, Installations, Environmental Art and Land Art movements — underwent a revival with the appearance of Neo-Dadaism. In the 1980s the last vestiges of tradition were destroyed, which for some was the negative result of what could be termed an over-developed culture.

My involvement in the Modernist movement had always been slight. I had also never had any desire to be confined by my own cultural traditions. My work was influenced by stronger cultural influences than mere nationalism. What I had managed to discover, I told him, was a new language: "Neo-Orientalism".

I first starting thinking along the lines of "Neo-Orientalism" in the early 1960s at the time of the Cultural Revolution in China. This was a time when 'real' art was forbidden and consequently thought replaced practice. Where, I asked myself, did the future of Chinese, and by association, my own painting, lie? Gradually, my ideas formed into a framework which became the basis for my work in the 1970s and 1980s.

The concept of "Neo-Orientalism" began to take shape through the examination of contemporary culture. On the one hand, an interest in primitive and Oriental art (Japanese prints) began to surface among European artists in the late nineteenth century, and to have an influential effect on their work. In the twentieth century Mark Tobey was influenced by Oriental calligraphy and Yves Klein studied judo in Japan. The Western perception of Oriental culture changed: from a mere curiosity, it became a subject worthy of serious study. Ancient Chinese philosophy, such as Confucianism, Daoism, the Yijing• and Zen Buddhism, attracted more and more interest in the West as a new attitude towards Oriental culture began to emerge. An example of this can be seen in the DOCUMENTA exhibition held in Kassel, Germany, every five years. While the main focus of this exhibition was contemporary European and American art, a supplementary exhibition, the K18 Exhibition, was also held focusing on the theme of "Contacts with non-Western Cultures", where the principal characteristics of non-Western contemporary art were presented. Similarly, both the recent Venice Bienale Exhibition in Italy and the Les Magiciens de la Terre exhibition in France were composed entirely from works originating from outside Europe and the United States of America. Whatever the purpose or success of these exhibitions, they represent firm proof that the art world in the West was starting to pay a great deal more attention to Eastern and non-Western art.

On the other hand, great changes have taken place in Asia since the end of the Second World War. China, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have begun to assume a more significant economic and political role in world affairs and new economic centres have developed in southeast Asia which have started to change the balance of the global economy. The time has come for Asian culture to assert its identity and assume its rightful place alongside its Western counterpart.

When I use the term 'Eastern', I am exclusively referring to China. That is not to say that a wider field of Oriental culture worth studying does not exist, merely that unlike most of the other great ancient civilizations, Egypt, Mesopotamia and India, which have largely lost their former glory, China alone has maintained a cultural tradition spanning five thousand years.

The first contact between Eastern and Western artistic traditions occurred during the Ming and Qing• dynasties when Jesuit missionaries came to China, bringing Western methods of painting with them. These methods had little impact, however, in face of the strength of Chinese artistic traditions at the time. Only in the twentieth century did traditional Chinese rise to the great challenge of Western art. Chinese intellectuals finally began to question the traditional values and ways of thinking only once the historical tragedy of China became evident after the Opium Wars. Since then, Chinese society has been subject to a series of Westernization movements, which have seen the systematic introduction of Western politics, economic reforms, philosophy, science and technology, and art and literature into China. This infusion of Western culture has fundamentally altered the social structure and cultural development of the nation.

In the 1980s, Chinese artists re-discovered the dignity and individuality they had lost during the Cultural Revolution. They now face a completely new dilemma, however. On the one hand, they face great difficulties in freeing themselves from new political constraints, the attractions of foreign culture and their reliance on traditional culture. On the other hand, the worldwide commercialization of art is a difficult temptation to ignore. In reaping the greater financial benefits on offer, artists are in danger of losing their spiritual and moral values.

This is a problem which is also coming to haunt Chinese society on a larger scale. The open door policy followed by China has led to the appearance of Western-style social problems: environmental degradation, feminism, racial prejudice and violence. After awakening from the political madness of Maoism, a new set of values has gained acceptance in China; that of greed and materialism. The big contrast between theory and reality and rich and poor has changed the spiritual make-up of Chinese society. The old beliefs have been discarded, but nothing has filled their void. The present generation is 'lost'. 'Official' art has lost its authority and its audience. In much 'unofficial' art we see dull and uninteresting images, the absurdity and coldness of which reveal a progressively more degenerate and cynical view of present-day life.

Chinese culture is in need of transformation. Not only is the visual language of art in need of reform as a means of enhancing national culture, but also contemporary culture must be re-examined in every aspect. In place of official art, art for amusement's sake and self-critical art, a new cultural system must be established which can cleanse and re-affirm the spirituality of life.

In using the term "Neo-Orientalism", I do so from the perspective of Western culture. A distinction must also be drawn between 'Oriental' and 'Chinese'. We unconsciously have a deep love as well as preference for our own culture which restricts our objectivity and prevents us from analysing that which is closest to us. When one is part of the established system, it is easy to lose direction. For that very reason I decided to withdraw myself from this system, to become, effectively, an 'outsider'. As a result, I now no longer suffer from the confusion I previously felt with regards to Chinese culture. I have become more sober-minded. My own opinion has been echoed in the words of the well-known art critic, Shui Tianzhong:• "Modern Chinese artists feel sandwiched between Eastern and Western art. They feel stranded in a valley and anxious to find a way out. They call themselves 'the tragic ge-neration'. Mio Pangfei, however, is different. He has learned and absorbed from both arts with an ease and confidence which befits his position on the 'outside'. Despite the tendency for the old to replace the new, the respect and understanding which "Neo-Orientalism" has for Oriental culture sets it apart from previous forms of Orientalism. The vision of the Orient which it gives us is not that fixed in the minds of European explorers and travellers, but that of Eastern artists who have a great knowledge and a deep love for their own culture, and who can extend out beyond their own national boundaries to re-establish Oriental culture according to Western concepts."2

In order to explain what "Neo-Orientalism" is, therefore, we must attempt to discover the point where Western and Chinese, contemporary and traditional, cultures meet.

§2. THE ATTITUDE TOWARDS TRADITION

A Bridge on the Sichuan Road, in Shanghai 上海四川路桥

MIO PANGFEI 缪鹏飞 (°1941).

Oil on canvas.

A Bridge on the Sichuan Road, in Shanghai 上海四川路桥

MIO PANGFEI 缪鹏飞 (°1941).

Oil on canvas.

The following is taken from the article Shizimen duihua pian•(Dialogue at the Cross Gate):

A — "As a Modernist painter, why is it that you appear trapped by the attractions and impulses of traditional aesthetics? Traditional aesthetics, which besides Chinese calligraphy and scholarly painting includes art from Giotto to Impressionism and even Egyptian, Mesopotamian, Greek and Roman art, is clearly displayed in your art, seemingly saying that you are unable to rid yourself of the influence of tradition."

R — "It is not really a question of not being able to rid myself of tradition, more one of not wanting to. Tradition is a fact. Some people consider it an overburdening presence, but I personally see it as an enlivening influence. This is not meaningless rhetoric but what I truly consider to be real. Change transforms tradition into a relevant entity. Studying and analyzing the styles from the past from a modern perspective permits them to be reevaluated and reassessed."3 Tradition can teach us many things once it has been redefined according to new concepts.

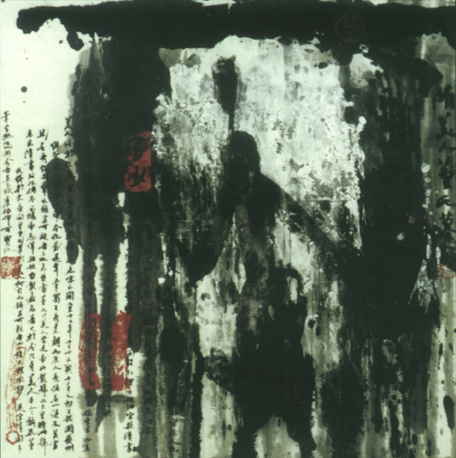

The old master Ling Fengmian· had the idea of giving up traditional scholarly painting and focusing his attention on Chinese folk art. Since there are generations of artists studying and refining traditional calligraphy and scholarly painting, it was a wise decision to take. And he has been highly successful since changing direction. Even if one chooses to withdraw from the cultural establishment, there are still many avenues within calligraphy and scholarly painting that can be explored. For example, my recent work "Zhengheng"• ("Conflict")4 is an extension of the art of calligraphy. There is also a wide range of other traditional Chinese cultural art forms worth studying and refining, from stone engravings, ancient bronzes, figurines, porcelain pictures, colour ceramics, masks, and eaves tile decorations, to puppets, leather silhouette shows, paper window decorations, guardian pictures, stone rubbing inscriptions, clay sculptures, murals, cave sculptures, cliff drawings, wall hangings, New Year pictures, military tallies, and royal seals, etc. Chinese folk customs are also rich. Traditional stringed music with drum accompaniment exists, as does village theatre and the so-called 'jiuqiu'• (lit.: nine turns'). This combines environment with performance, the whole project requiring three hundred-and-sixty oil lamps and flags to create a mysterious atmosphere of either magic or religion. 5

China is rich in underground treasures. Ever since the discovery of the Dunhuang• cave murals, ever more cultural artefacts have emerged, such as the turtle-back inscriptions of the Yin•-Shang• dynasty (16th-11th centuries BC), the bronzes of the Shang and Zhou• dynasties (16th-3rd centuries BC), and the stelae inscriptions of the Northern Wei dynasty (AD 4th century), etc. While he was alive, the famous master Huang Binhong• sensed that the revival of Chinese art was imminent. At the time, his opinions were never taken seriously. Later, however, a great many artefacts were discovered, including figurines, eaves tiles, murals, stone carvings, bamboo writing slips and other utensils, which led to a great upsurge in academic study. Modern Chinese art did not benefit greatly from this explosion of interest, however. 6

If a way can be found to combine timeless spirituality with our own mission, and the law of the development of art with the sensitivity of Chinese history, then we will be able to discern modern life from ancient art forms.

§3. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN EASTERN AND WESTERN CULTURE

An unequal dialogue presently exists between Western culture, namely European and American, and other 'marginal' cultures. European and American cultural systems have become international. Western philosophy, science, democracy, values, lifestyles and art over the centuries have greatly influenced the world and have come to form the basis of the cultural system and lifestyle of contemporary society. No other cultural system has managed to exert such a strong global influence and therefore, as a logical consequence, the West has become the cultural centre of the world. As yet, marginal cultures have not developed a strong enough international voice to make any impact on this hegemony.

However, it must be questioned whether the extremes of cultural phenomena that have arisen are in any way productive. The modern spirit of rebellion and criticism has died away to be replaced by a movement emphasising anti-rebellion. This new culture, or anti-culture, can only lead to new problems. Cynicism and the shattering of beliefs will push society into a deep spiritually-void crisis.

Contemporary art is becoming more and more commercialized. Art is practical and utilitarian and often relates to the conflict of interests between the individual and the group. Contemporary art finds itself in a cultural no-man's land after the 'suicidal' period of Post-Modernism. Marginal culture and artistic conscience should therefore be promoted as a means of producing a more rational culture as well as a more rational society.

Looking for the meeting point between traditional and contemporary culture, Zhuang Zi, • the ancient Chinese Daoist philosopher, expressed the need for spirituality in art. In the essay Paoding jienu• (The Butcher Slaughters the Cow), he sets out his ideas through the words of a butcher: "What I am striving for is the Great Dao. When I first began to slaughter cows, all I saw was cows. But after three years, I no longer see cows." The butcher's act of slaughtering is transformed from a mere skill into a spiritual act. In fact, as the writer mentions in the same essay, it becomes an act of artistic creation and a source of artistic enjoyment: "Meeting the mind instead of the eyes. The senses know when to stop but the mind wants to continue. This is the Great Dao fitting into Nature." The great problem facing popular culture today, however, is that the spiritual side of art has been completely engulfed by materialism.

Art has no immediate effect or use. Writing, meanwhile, is a practical activity. When, however, in the form of calligraphy, it is elevated to the status of an art, and thus a spiritual activity, it loses its practical value, becoming "useless". "What is useless has great use." Here is a fundamental assessment of the value of art. In his essay Renhijan• (The Human World), Zhuang Zi states: "Only when one understands what is useless can one speak of what is useful.".

In the essay Waiwu• (The Things Outside), Zhuang Zi tells all those striving for the Great Dao (we may think of them as people pursuing art) to forget everything and to free themselves from 'use' in order to ascend to the state of beauty, which is spiritual freedom. This process of forgetting is a form of purification. As Zhuang Zi says, "[...] the spirits of Sky and Earth [...]" are the painter's greatest inspiration. The exploration of one's inner world and experience of life is the road to freedom and independence from external controls. In other words, the 'false I' who is controlled by materialistic needs must be discarded in order to reach the 'Real self'. It is this very spiritual aspect which is most lacking in contemporary culture today.

The spirituality of ancient Chinese philosophy, Confucianism, yin• and yang,• Yijing and Zen Buddhism, permeates every aspect of Chinese culture. Chinese medicine, Qi Gong,• literature, painting, music and theatre have all combined to form a distinct Oriental culture which has had a great influence on the development of world culture. The importance of this culture, and the basis upon which it rests, spirituality, explains why we must re-study ancient philosophy if we hope to re-establish a healthy culture and a rational society. For this to be achieved, the interaction between cultures and philosophies from East and West must also be examined.

There is an essential difference in the way of thinking between the East and West. In the West, emphasis is placed on methods of analysis and the definition of concepts. Oriental philosophy, however, focuses on the inexplicable experience of man's inner world, on achieving enlightenment. In art, Chinese tradition emphasizes 'Qi', which means 'vital spirit'. This differs greatly from the concept of 'Imaginary space' invented during the European Renaissance.

In Guhua pinlu• (Critique of Ancient Painting), the ancient Chinese art critic Xie He, who lived during the Southern Qi• dynasty (5th century), asked: "What are the six principles of painting? The first is the vital spirit." Guo Rouxu• of the Song• dynasty (10-13th centuries), also in reference to the six principles, stated: "The six principles are the classical cannon which will never change." Both comments reveal the importance with which the six principles were regarded and, through inference, the vital spirit. According to Dong Qichang•, the great painter of the Ming dynasty (14th-17th centuries), "The vital spirit cannot be learned. It is a natural gift." He also added: "Nevertheless, there are a lot of things to be learned. One must read ten thousand scrolls and travel ten thousand miles. Then one may clean away all the dust and filth from one's chest." A natural gift also needs cultivation, therefore. However,in traditional scholarly painting, 'Qi' is always opposed to 'Form'. Su Dongpo, • the great poet of the Song dynasty, said: "If a painting is merely realistic, it represents nothing more than a child's perception."• In Jiu Fanggao xiangma• (Jiu Fanggao Discerning the Horse) he states that Ji Fanggao• is a great master of the horse even though he cannot distinguish which is male and which is female. Bole,• another great master of the horse, said: "The way Gao discerns the horse is nature's mystery. He can grasp the essence and forget the rest, get the inside and forget the outside. He sees what is necessary and never sees the unnecessary." This, if we take it a step further, would seem to be the basic prerequisite for an artist. Shen Kuo•, in Bixi mengtan• (The Writing besides the Dream Stream), states: "The most important thing for an artist is to achieve perfect unity of mind and hand. Strength comes from natural inspiration." This, I think, explains the mystery behind art.

The above guidelines were the inspiration behind a series of works I have undertaken. For example, some of the elements in "Shengsitu"• ("The Picture of Life and Death") are taken from the facial imagery seen in Beijing Opera, which has then been transformed into organic images. The "Shuihu xilietu Wu Yong biantihua zhi si"• ("Fourth of Wu Yong Version") in the series of paintings on the well-know Ming dynasty novel Shuihu• (Shuihu), is similar in its treatment of colour to the sanzai• ('three-couloured') pottery of the Tang• dynasty. The "Taoli tu"• ("Peach and Plum") is derived from folk art, but the image created is purely Western. 7

Based on several thousand years of tradition, line is the most essential element in Chinese painting and calligraphy. Western art also makes use of line but in a very different way. Besides its relation to form, the manner in which line is employed often expresses, in a natural form, the painter's personality and temperament. Tradition also dictates correct brush techniques. As Zhang Yanguan, of the Tang dynasty, once said: "Structure, spirit and form all stem from the brush."

Whatever the weight of tradition, however, cultural characteristics must be re-assessed according to modern concepts. In such a manner, cultural language can be enhanced and purified and a completely new discourse with modern aesthetics cultivated. This is an approach which differs significantly from that prevailing in the West at this moment.

Strictly speaking, today's world is the product of Western culture. In recent centuries, cultural forerunners such as Picasso and Marcel Duchamp systematically changed the values and concepts on which modern society is based. If Chinese art remains unfamiliar with the ideas and techniques of Western art, it will be limited to perpetuating traditional forms, in the manner of the old Chinese literati masters, or studying folk and decorative art. Finding modern expression would then become an impossible task.

It used to be said that "Art would be more international if it were more national." The logic behind this statement is unfounded quite simply because it neglects the relationship between time and art. Art, after all, is a product of its time. There is a tendency amongst those engaged in traditional art forms to forget this fundamental issue of contemporaneity. The modern age has been moulded by the productive forces unleashed in the West. Western philosophy, science, culture and art in this century all reflect the historical movement that those productive forces brought into being.

The historical experience of China this century has been significantly different, however. The defining movement in recent Chinese history has been nationalism, which offers no challenge to Western modernism. A new cultural system cannot be established if Chinese painters do not understand and practice traditional art. This is essential if a concept and language other than that developed in the West is to be promoted.

My own art has always been influenced by both cultures. From the 1950-1960s, I studied Western traditions of art; the Russian drawing system, and the European realist masters such as Rubens, Rembrandt, Velasquez etc. Gradually, I turned to Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, Cubism, and eventually, to Abstract painting. In the 1960s- 1970s, I discarded Western in favour of Chinese art. Here, I concentrated on two aspects. The first of these was calligraphy: Zhuan style (the engraving of ancient style Chinese characters on bronze vessels), di• (the inscribing of ancient style Chinese characters on stelae) and xing• ('grass style'— the calligraphy of old masters such as Huang Shangu, • Mi Fei,• and He Shaoji). The second was painting. The painters I studied were those I felt most closely mirrored my own style. These included masters who were working at the beginning of this century, Huang Binhong, Wu Changshuo, •, and also others from earlier eras, Shi Xi, • Shi Tao,• Shen Zhou• and 'the four masters' of the Yuan dynasty. They all belong to the Southern school of Chinese art. I also studied the Dunhuang cave murals of the Northern Wei,• Northern Liang,• and Northern Zhou• dynasties, as well as the tomb murals of the Han• dynasty, and folk art. My next step was to try and combine the techniques of both Eastern and Western painting. In the mid-1970s, I was mainly interested in experimenting with tools and materials. But throughout these years of experimentation, I always paid close attention to cultural developments and trends both inside and outside China.

At around the turn of the century, Chinese painting entered a new period known as 'seal cutting', referring to a new style of brush stroke and line. To a certain extent, art forms became abstract and symbolic, and similarities could be seen with Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and other, later styles. It is very interesting that similar trends should have appeared on both sides of the globe at the same time. The huahui• ('bird and flower') style paintings of the Chinese artist Wu Changshuo's• are almost written rather than painted in a very similar way to calligraphy. The landscape paintings later produced by Huang Binhong display elements of deconstructionism, in that details are resolved into separate points and lines. If dialogue is to be achieved between art from the East and the West, then it will undoubtedly be based on the recognition of abstract elements.

From a personal perspective, the study of abstract elements plays an extremely important role in my own art, allowing me to express my desire for oriental ideas and humanity. What is more, it will form the essential basis, of "Neo-Orientalism".

What, then, of the future of "Neo-Orientalism"? It will, I believe, become the very core of artistic activity for a whole generation of Eastern literati. Does it belong to the ancient Orient, or to today's West? Or will it become the common cultural reference point for both East and West in the future? "Neo-Orientalism" is an examination of Eastern culture from a Western perspective. It absorbs and reforms tradition, transforming it into artistic language. It uses the calligraphy, signs, brushstrokes and colour (ink) of Oriental art. It contains the 'vital spirit' of Chinese tradition, is filled with the inspiration of enlightenment and it is expressed through Western concepts. It uses the most effective media, materials and methods, such as displacement, separation and reconstruction, to arrive at many different layers of meaning. It is filled with a concern for humanity and the meaning of life.

Orientalism, as a global art form, will bring East and West together in cultural harmony, engineering a new path to enlightenment and thus challenging the superficiality of today's popular art. It is art bridging the gap between past and present. It is destined to become the common spiritual expression of mankind in the future.

Dongshi's Grave-A Beauty of the Sui dynasty 隋美人董氏墓

MIO PANGFEI 缪鹏飞 (°1941). Watercolour.

NOTES

1 XIAOFENG, Huang 黄晓峰, • Aomen xiandai yishu he xiandai shi pinglun 《澳门现代艺术和现代诗评论》 (A Review of Macao Modern Art and Poems), section: Shizimen 《十字门对话篇》 (Dialogues at Cross Gate).

2 TIANZHING, Shui 水天中, • Mio Pangfei he ta de xin dongfang zhuyi 《缪鹏飞和他的新东方主议》 (Mio Pangfei and his Neo-Orientalism).

3 XIAOFENG, Huang 黄晓峰, op. cit., section: Shizimen 《十字门对话篇》 (Dialogues at Cross Gate).

4 “争衡”("Conflict") — 1995, mixed media, 324.0 cm x 480.0 cm.

5 “初民图” ("People of Chu"), “神龟图” ("Sacred Tortoise"), “水浒系列图之吴用变体画之一”(局部) ("The "Outlaws of the Marshes" Series: Wu Yong I" (Section)), “有鱼图” ("Fish), “水浒系列图鲁智深变体画之一”(局部) ("The "Outlaws of the Marshes" Series: Luo Tsu-sun I" (Section)), “地下文明图” ("Underground Culture"), “水浒系列图卢俊义变体画之三”(局部) ("The "Outlaws of the Marshes" Series: Lung Chun-yi III" (Section)): Ills. pp. 44, 72, 74 — Refers to stone sculptures on Xiaotang Shan and the tomb of Ho Chubing; ills. pp. 40, 43, 62 — On relief sculptures; ill. p.52 — On writing on bamboo strips; ill. p.38 -- On murals.

6 DEFU, Jian 姜德溥, • Mio Pangfei zai Shanghai 《缪鹏飞在上海》 (Mio Pangfei's Life in Shanghai).

7 “生死图” ("Life and Death"), “水浒系列图吴用变体图”(之四) ("The "Outlaws of the Marshes" Series: Wu Yong IV" (Section)), “桃李图” ("Peach and Plum"): Ills. pp. 49, 53, 73 — On the handling of the brushwork.

start p. 175

end p.