INTRODUCTION

Macao, a small city on the coast of south China, close to Hong Kong, was the first permanent Western port settlement in the Far East. The Portuguese managed to install themselves there, between 1552 and 1557, at the mouth of the Pearl River, overlooked by a temple dedicated to Ama from which the city's Western name has derived. Soon Macao became a hub for constant, profitable trade with the Far East, serving as a gateway into China and generating trade between China and Japan which lasted for around one hundred years (1543-1639) and for the Western commercial monopoly over China until the creation of Hong Kong in 1841.

For these reasons Macao has been a meeting point for the most varied people until the present, and it is still a cosmopolitan city. Its History is one of the most important relating to contacts between East and West since the sixteenth century, although not always well covered by the historiography of Asia.

The passage1 of individuals through Macao occured due to a plethora of different reasons, mostly commercial, diplomatic — such as the wellknown embassy led by Macartney (1792-1794) — or scientific — such as La Pérouse's expedition (1787) or that by the survivors of Cook's last trip in 1779 —, but also the propagation of the Catholic faith and the search for a safe refuge. For these reasons Macao was the stage for numerous adventures and a safe port in passing for all kinds of unusual and controversial figures.

This was the case of Count (or Baron) Benyowsky (°1746-†786), a little known adventurer who accidentally appeared and was made welcome in Macao in the late eighteenth century. His brief life held more than its fair share of trials and tribulations, and reflected the restless, brave, courageous nature of the classic Romantic figure, a man without roots, a traveller.

Of Polish origin, Mauritius Augustus Benyowsky (Móric Benyovzky) was born in 1746 in the county of Nyitra in present-day Slovakia. He was the son of Count Samuel Benyowsky, a cavalry General in the Austrian army.

He enlisted in the Austrian army at a very young age (in around 1758) and fought in the Seven Years War (1756-1763). Later, as a result of disputes which arose when relatives appropriated the inheritance he was due on the death of his father,Benyowsky was declared persona non grata and stripped of his property by Maria Theresa of Austria. He fled the country and settled in Poland, travelling through Britain and Holland where he studied the arts of sailing and shipbuilding.

Although he began to prepare to leave for India in 1766, in 1768 or 1769, he joined the confederated Catholic troops2, fighting bravely to protect Poland which was by that point already under the political yolk of Russia. Thanks to its greater military strength, Russia had been able to place Stanislaw II on the throne in 1764. Following various incidents, including a conspiracy against the King himself in 1768, Benyowsky was imprisoned by the Russians in Krakow in 1769 and exiled to Kazan, now holding the rank of Captain. Although he was placed under guard, he enjoyed a free life and was able to participate in a fresh conspiracy, this time against the Russian government. When the uprising was overthrown, the Count and his companions-in-arms were exiled once more, this time to Siberia.

Benyowsky arrived in Kamchatka, on the 2nd December 1770 after a journey lasting almost one year during which he tried to escape on several occasions. Forced to earn a living in exile, he taught French to some pupils including the children the city's Governor, Niloff, winning the latter's confidence. However, he never gave up hope of escaping. After Benyowsky's plot was discovered, there was an armed struggle which led to the death of the Governor and left the Count injured. In May 1771 he commandeered a naval vessel, the "corvette" [sloop] St. Peter and St. Paul, and managed to flee with his companions. All in all, the boat carried around ninety six people, most of them soldiers but also five or nine persons dressed as women.

There can be no doubt that one of them was Aphanasia, Niloff's eldest daughter, an act which led to the story of a romance between the two. Marques Pereira3 insists on this Romantic vision and the belief that it was Aphanasia who opened the prison gates for the Count, thus betraying her country and her own family (given that her father was Governor). He is convinced that the young woman died in Macao, either abandoned or from shock, on finding out that her lover had prior marital commitments.

The Count had planned to escape from Kamchatka to Guangzhou from whence he hoped to sail to Europe. His voyage was, however, extremely difficult. They sailed at the height of the typhoon season and their ship was blown as far as the coast of California, passing through the Aleutian islands. From there he sailed back to the West, dropping in at the Kurila and Bering islands and at Japan. On the 14th of August he dropped anchor at Usmai Ligon, an island located at twenty-nine degrees North. 4 From there he sailed to Formosa where more adventures awaited him.

§1. FIGHTING ON THE PRINCE HUAPO'S SIDE

He sailed to Formosa at his companions' demand — they had heard about the island and intended to visit it in search of new adventures. 5 Arriving on the 26th of August they first dropped anchor on the East coast at 23° 32' North, fifty miles North of Pilam.

But first contacts with the natives were not so friendly. The Count was forced to fight6 them in order to defend the members of his own party who went ashore in search of fresh food.

After the incident they left and headed North where they found an excellent harbour named "Port Maurice"7 by the Count, where they anchored.

Offered fresh fruits, rice and other supplies, the visitors received friendly welcome by the inhabitants who were commanded by a European dressed in a strange way "[...] partie en européen, partie à la manière du pays [...]" ("[...] half in the European way, half in the country way [...]"); 8 called Don Hieronimo Pacheco.

Don Hieronimo, a former Cavite port (Manila) captain was himself a refugee from the Philippines for having killed both his wife and a Dominican priest, as he had caught them in flagrante, seven or eight years before.

Once in Formosa he became the confidant of several tribes and remarried with a local woman who had already given him several children.

Benyowsky and Don Hieronimo got along nicely. The Count offered him a complete uniform, several shirts and one sabre and even suggested he join his own party and depart to Europe. But the Spanish answered "[...] qu'il la connaissait assez et qu'il remerciait le Ciel d'en être sorti." ("That he already knew [the Europe] and that he thanked Heaven by being aware of it.")9 and added that he was already used to the wild life, that he had a reputable wife and lovely children that he did not want to lose at any price. Davidson10 gives us a perhaps more real account: "To secure the aid of this man as interpreter and friend, Benyowsky gave him valuable presents and promises of more if he found him faithful during his stay at the place."

Don Hieronimo got the chance to persuade the Count to take Prince Huapo's11 party — a powerful native chief who could muster over twenty thousand men — in war against the Chinese12 invaders and neighbour' tribes, who were quickly exterminated. 13 The military superiority of Benyowsky's men equipped with muskets and swivels guns against the lances and the arrows led to a complete victory over the enemies and to the Prince Hapouasingō's surrender. He was the Huapo's most important adversary14 and an ally and a tributary of the Chinese.

According to Formosa's historians, we also know that Benyowsky had been introduced to Prince Huapo by Don Hieronimo as: "[...] un grand prince qui visitait Formose avec l'intention de se rendre compte de la position des Chinois et de délivrer les habitants du joug de ce peuple." ("[...] a great Prince who intended to visit Formosa with the pourpose of evaluate the extent of the Chinese domination over it and how to free its inhabitants."). 15 On the other hand, the Prince had shown himself persuaded that"[...] the Count must be the stranger predicted by their divines, who was to break the Chinese yoke from the neck of the Formosans."16

Following the same sources, a kind of 'Treaty' had been established between Benyowsky and Prince Huapo who "[...] entered more into the details of his plans, and left no reason to doubt that vanity induced him to declare war upon the Chinese [...]," according to Davidson, 17 who also points out the Count's position and way of persuading the Prince: "[...] as the count already cherished the idea of returning later on and founding a Colony on the island, he foresaw that the friendship of a native chief would be very serviceable, not merely on the ground of present safety but also by rendering the proposal of a Colony more reasonable in the eyes of some European power. He resolved, therefore, to secure by all means the friendship of Huapo. For this purpose he showed him the ship, gave him an exhibition of fireworks, and upon retiring, the chief gave in return his belt and sabre, as a token that he would share with him the power of the army. The Count also prepared presents for the chief, consisting of two pieces of cannon, thirty good muskets, six barrels of gunpowder, two hundred iron balls, besides fifty Japanese sabres, probably a part of the spoil from a Japanese junk which our adventurers had previously captured."

As a reward for his military support Benyowsky had been promised Prince Huapo's support in establishing a Colony in Formosa to be settled in Hwangsin's department, economically based on the commercial exchange of local products such as gold, crystal, cinnabar, corn, sugar, cinnamon, and mostly its. fine woods, in exchange for European products such as iron and stuffings.

The 'Treaty' terms are closely described by Davidson18 as followed:

"That the count should leave some of his people on the island until his return; that he should procure for the prince armed vessels and captains to command them; that he should aid him in expelling the Chinese, on condition of receiving at once the proprietorship of the department of Hwangsin, and when completely successful, that of his whole territory; that he, the count, should assist him in his present expedition against one of the neighboring chieftains, in consideration of the payment of a certain sum of money and other advantages; and, lastly, that they should enter into a permanent treaty of friendship.

To all these propositions, except the first, the count assented, and stated the cost of procuring the required supplies of men and shipping. They then prepared to ratify the agreement of perpetual friendship, by means of ceremonies19 very similar to those which are observed in several islands of the Eastern Archipelago when a savage chief would assure a guest of his friendship.

When these ceremonies were ended [Davidson adds] the count was dressed in a complete suit, after the fashion of the country, and was received with every demonstration of joy. Accompanied by the chiefs, he rode through the camp and received the submission of all the officers, which was signified by each touching with his left hand the stirrup of the count."

It must be said that before he had committed himself to giving military support to his new friends, Benyowsky had previously consulted his party, who were particularly well impressed with the island's resources and beauty.

As Imbault-Huart points out it seems that it was an arduous task for Benyowsky who "[...] eut beaucoup de peine à decider ses compagnons à quitter Formose: tous, trouvant le pays si beau et si riche, voulaient rester dans ce séjour enchanteur; ils essayèrent de persuader leur chef de fixer sa résidence dans la province que Houapô leur cédait; ils représentèrent que leur troupe était suffisante pour fonder une colonie et que, plus tard, on pourrait envoyer des émissaires par la voi de Chine, pour enganger quelque puissance européenne à s'intéresser à la colonie naissante, ou, en tous cas, lever des recrues." ("[...] to persuade his companions to leave Formosa: as all of them found the country so good and rich that they would like to remain in this enchanted isle; they tried to convince him to be stationary in the province offered by Prince Huappo; they added that his troops were good enough to start up the colony and that it would be possible for them to send, later on, through China, some envoys to some European country asking for support to the new colony or, even, requesting recruits."). 20

The most important reason presented by Benyowsky to reject both his companions' and Prince Huapo's proposals to remain in the island was that he was married and had a child and mostly that his own presence in Europe should be more convenient for the common project. And he clarifies: that "[...] une personne sur les lieux valait mieux qui messages écrits [...]" ("[...] one person on the spot is more valuable than several messages [...]."). 21 and also that he was sure that, once in Europe, he would be able to get the support of some powerful country, as soon as he could convince them of some advantages such as, for example, the opening of commerce with Japan! Even, in case all those intents failed the Count, to whom it seemed that impossible jobs, did not exist, concluded that "[...] si aucun gouvernement ne veut nous aider, [...] il nous sera toujours loisible d'exécuter nos projets à nos risques et périls!" ("[...] without a foreign government's help [...] we will always be in position to pursue our intention at our own risk and using force!"). 22

FACING PAGE:

Hungarian Man.

"Hungary is South of Bosnia. The Hungarians look like the Mongols. They usually dress in short vests and trousers, close-fitting, to their legs. They are intelligent and courteous. Expert horse-riders, their short necked horses are extremely fast. They usually carry daggers 4 chi long. They cavort their horses, and whenever they ride [them] they spin and turn brandishing curved swords 4 chi long."

In: The Tributaries Scroll of the Qianlong Emperor, in "Review of Culture", Macao, 2(23) April/June 1995, pp. 33-55, pp. 38-39.

FACING PAGE:

Hungarian Man.

"Hungary is South of Bosnia. The Hungarians look like the Mongols. They usually dress in short vests and trousers, close-fitting, to their legs. They are intelligent and courteous. Expert horse-riders, their short necked horses are extremely fast. They usually carry daggers 4 chi long. They cavort their horses, and whenever they ride [them] they spin and turn brandishing curved swords 4 chi long."

In: The Tributaries Scroll of the Qianlong Emperor, in "Review of Culture", Macao, 2(23) April/June 1995, pp. 33-55, pp. 38-39.

After sixteen days of a busy sojourn in Formosa, Benyowsky was able to leave on the 12th of September to Macao, but not before Prince Huapo had shown his gratitude. According to our sources he offered the Count and his party valuable presents of which he "[...] distributed the whole [...] among these associates, officers, and women, reserving nothing for himself. [...] This act of generosity[adds Davidson]23 gave him unbounded influence over his companions, but no more was necessary, as immediately appeared [...]," referring to the already appointed reluctance of his party to leave Formosa. We will later address this subject with some more detail according to its relevance to events during the Macao stay.

Once again Davidson24 seems to be more faithful as he says that Benyowsky's military help had been promised "[...] in consideration of the payment of a certain sum of money and other advantages." In any case, Benyowsky says that he received "[...] some fine pearls, eight hundred pounds of silver, and twelve pounds of gold [...]"25 and "[...] for his private use [...] a box containing one hundred pieces of gold which together weighed thirteen pounds and a quarter, and the general was charged to attend him with one hundred and twenty horsemen and to provide subsistence [...],"26 despite his considering it very doubtful. 27

Before leaving, the Count gave written instructions to Don Hieronimo to follow up their projects and "[...] left with the chief the parteraroes, whose usefulness he had seen so fully tested [...]."28

Furthermore, he gave him permission to keep a young boy with him to learn the native language and to help him until his return to Formosa... Loginow, who had just lost his brother in the recent fights in Formosa was the chosen one.

It seems that once in Europe the Count did not forget29 this commitment and even offered — probably without too much credibility30 — "[...] to the country which would support him [...] to pay an annual tax, to assist his patron in time of war with soldiers and sailors from the island, and furthermore he guaranteed to return all funds invested with interest within three years [...].",31 but he never returned to Formosa.

§2. IN THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF MACAO

The party took around one week to sail from Formosa to Macao, where they finally dropped anchor in Macao on the 22nd of September 1771 after five long months at sea.

Benyowsky's Memoirs [...], published by Teixeira32 from the entry on the 11th of September 1771 when he was still on Formosa, allows us to follow the voyage from Formosa to Macao, and the party's stay in Macao and Canton until setting sail for Europe. The most interesting, unusual points shall be transcribed and examined.

They came into contact with the coastal fishing communities in the region and were able to arrange two pilots who, for one hundred piastres, 33 brought them into Macao. It is interesting that Benyowsky was able to communicate with these men (although with some difficulty) by speaking Portuguese, 34 the lingua franca of the seas. These pilots guided him to Tanasoa35 because, in the words of the pilot, "[...] Mandarin hopchin malas, Mandarin tanajou bon bon malto bon [...]." in other words, as Teixeira clarifies, "[...] the Mandarin of Hopchin is wicked; the Mandarin of Tanajou (Tanasoa) is good, good, very good [...]."36

In fact it seems that the pilots were absolutely correct as the foreigners were able to establish very cordial relations with the authorities at Tanasoa, despite the fact that the Chinese were somewhat surprised at encountering Hungarians in their country. The mandarin who paid a visit to the ship with an interpreter required them to explain their reasons for being there and state where they were going. All the information was noted down by the Chinese official and then he gave permission for some men to go ashore to stock up on necessary provisions. Benyowsky, who had introduced himself as "[...] a European and one of the nobles of Hungary; that the ship belonged to the Russians but having taken it from them, who were my enemies, it now belonged to myself; that I came from Kamchatka; was on my return to Europe, and proposed to put in at Macao [...]," politely sent ashore two of his officers, carrying a beaver skin and two sables as gifts for the Governor of the area. Following the rituals of Chinese étiquette, the Governor responded by offering a porcelain dinner service, two chests of tea, six cows, a dozen pigs, poultry and "[...] a kind of arrack [...]." In turn, Benyowsky's envoys returned with "[...] a hundred different kinds of sweetmeats, and some toys, very nicely wrought."

The detailed account of Benyowsky's adventures by the Chinese authorities is not surprising: at the time the Chinese had what Europeans regarded as a model administrative structure. China took particular care in inspecting its coastal regions and so this kind of report was normal. There was something more, however, to their interest in other peoples. On orders from the Qianlong Emperor (°1736-†1795) a record was being compiled of information on minorities and foreigners with whom China came into contact. This information served as the basis for the famous Tributaries Scroll, a work in which China sings its own praises over its contribution to the pacification of the world. 37 Obviously, it is not my intention to imply that Benyowsky contributed directly to the above-mentioned work — particularly in view of the fact that a large portion of it had already been completed by 1760. Rather I wish to emphasise China's openness to 'the other' during the eighteenth century, even though dictated by an approach based on hegemony and superiority, and despite the geographical and other errors contained in the document. What we do know is that the mandarin of Tanasoa was perfectly able to identify them as Hungarians and as such was surprised to see them in China, his curiosity naturally whetted by the event. 38

In addition to the protocol, the Count also describes what we can regard as the normal mode of behaviour on these occasions — smuggling, which seems to have been lucrative, and its pay-off in the flower boats. 39

The intense maritime activity that still marks the South China Seas was not lost on the Count. Following on from this, he describes a tributary fleet. 40

Another aspect of the voyage and the party's stay in Macao that Benyowsky takes care to note in great detail is the travellers' state of health, including his own, and their opposition to his command. In Macao, after the death of a significant number of his companions, he reaches some conclusions as to the insalubrious nature of the climate. Although this is a common thread running through almost all the accounts of European travellers in China — who indeed were subject to much higher rates of mortality — it is also true that the conditions under which Benyowsky's voyage was prepared and took place did little to promote the good health of the participants. Benyowsky himself suffered from a violent fever near the Ladrone islands41 as the ship drew near to Macao. His Chinese pilots recommended a remedy which he notes in his Memoirs [...]: "[...] an orange, roasted in its juice, with sugar, and a good deal of ginger; they prepared this remedy for me, and it produced a strong perspiration, which dissipated my complaint."42

The Count also provides some information on sailing conditions and the route plied from Formosa to Macao. They sailed primarily by coastal navigation at the demand of the pilots. Benyowsky displays a concern with record-keeping, as would a true captain, along with an interest in pursuing his knowledge of geography and natural history. He even managed to include a Japanese and an American at least in his party although it is not clear how this came about. All of this points to the significance of the Count's travel notes, records which would be greatly coveted in Macao as shall be discussed below.

He provides little information about his ship, which he describes as a "corvette ", other than its draught. We know that it required more than eight feet of water to sail for it was because of this that the Count had to wait for the tide on the 19th of September. He used this opportunity to note the existence of under currents in the region of 22° 32' North.

The documents held in Macao note his vessel as a "chalupa" ("sloop"), a description followed by Benyowsky himself. However, sailing vessels in the period were often subject to vague classification and were sometimes given more than one description. 43 In view of this, I would proffering risk44 of stating that the Count arrived in a sailing ship with two masts and rectangular sails, which would have been highly mobile and a loading capacity of between two and three thousand piculs, 45 despite its description, in the English records quoted, as having an "[...] unusual appearance [...]."

The final stage of their voyage to Macao has still to be covered. Two days after the entry concerning tides and currents, they anchored at about six o'clock in the evening at Ladrones island. From there they set off again on the 22nd of September, taking five hours to catch sight of Macao. They came into port at around two o'clock in the afternoon, according to Benyowsky's log.

§3. RECEPTION, STAY AND BUSINESS IN MACAO

When Benyowsky arrived in Macao on the 22nd of September 1771 with his depleted company of sixty five (all of them suffering from bad health), the party was welcomed with generous hospitality and provided with accommodation and food until their departure, paid for predominantly out of the city coffers. Benyowsky was given an audience with Governor Diogo Fernandes Salema de Saldanha (1771-1777) on the day that he arrived. He asked him for protection and assistance, not only for himself but also his companions, "[...] having arrived at this city by necessity and in the final stages of human endurance [...],"46 requesting "[...] permission to rent houses in the town and to accommodate my people, till I could find a favourable opportunity of conveying them to Europe." To avoid suspicions the Count placed his ship "[...] as a deposit, in the hands of the Governor." Similarly, his weapons were "[...] likewise deposited in the castle [...]" (Mount Fort) [Port.: Fortaleza do Monte], apart from those which were deemed indispensable for the personal protection of each of his companions. The Governor gave his permission for them to rent houses until such time as they could return to Europe. The Governor charged a certain Hiss (or Hies), a Frenchman who had been living in Macao for a long time, to assist the Count and his party and to serve as interpreter.

Let us introduce here the issue47 of allowing foreigners to enter, reside and trade in Macao. This was one of the most divisive, constant issues to be debated in Portuguese administrative circles or to be discussed by the Portuguese and Chinese during the eighteenth century. The major European powers had been trying to gain a foothold in China, particularly Guangzhou, since the previous century. Because of Macao's proximity to China, it was the target of repeated attempts to gain control. The fact that during the same period China swayed between granting permission (1685; 1730; 1757) and placing restrictions or prohibitions (1717; 1725; 1760) on direct trade with foreign countries meant that there was ever-greater interest in seeking out Macao as an alternative. This also fell in with the imperial desire on several occasions (1719; 1732) to limit China's foreign trade to the city of Macao. 48

Consequently, the Portuguese administration frequently issued prohibitions on commercial exchange with foreigners in Macao going so far as to forbid them from residing in the territory as is the case of the Carta Régia (Royal Letter) dated the 9th of March 1746, sent from Goa on successive occasions throughout the rest of the century (1757; 1773;1776).

This became a futile exercise in 1760 when the Qianlong Emperor who promulgated the well known Eight Regulations49 concerning trade with foreigners50 in Guangzhou — open to all the countries since 1730 —, making Macao an integral part of this process, although it had refused to be the centre for it. It meant that the French and Dutch Companies were able to establish themselves in Macao in as early as 1761. They were followed by the Danish and Swedish Companies with the English only arriving between 1771 and 1773.

But the issue was still debated long after this period and it was only in the following century, on the 20th of November 1845, that Macao was declared a free port.

Until then the Macao merchants found some alternative solutions.

Consequently, in exchange for entry into the Territory — where, contrary to Guangzhou, trade could be conducted throughout the year — it was compulsory for foreign traders to be associated with local agents. Lord Macartney, the British ambassador who visited China between 1792 and 1794 in order to gain a more stable trading status for his country or even a territorial base like Macao for storing products and allowing their nationals a place for transit, reported:

"The Portugueze settlers lend their names, for a trifling consideration, to foreigners belonging to the Canton [Guangzhou] factories, who reside part of the year at Macao. These, with more capital, credit, connections, and enterprize, are more successful; but require to be nominally associated with Portugueze, in order to be allowed to trade from the port of Macao."51

According to William C. Hunter, from 1772, Macao became the "[...] summer resort of the residents of Canton [...]."52 Foreigners had to introduce somebody who would take responsibility for them selected from amongst the residents of Macao. They also had to state how long they intended to remain. All these procedures were retained until the late nineteenth century, as the author reports.

The fact that this was a non-official practice dictated rather by the people of Macao's extraordinary ability to adapt to new situations has been demonstrated over the centuries. According to G. Bryan de Souza53 this must have been one of the greatest sources of income for local traders at the time.

Coming back to Benyowsky, two decisions were taken by the Leal Senado** to help the Hungarians, on the 16th of October and on the 7th of December 1771. They state the Senado's desire to assist the travellers by paying for their food, accommodation and officers' and soldiers' salaries.

All in all, Benyowsky and his party enjoyed Macao's hospitality, a fact noted by the Count although with a certain distance and indifference. The Governor, whom Benyowsky calls "Mr. Saldagna" [sic], not only provided the assistance referred to above, he also made personal gestures such as providing him with furniture from his own palace so as to fit out his quarters in the appropriate manner. He also visited him in the company of two of the city Fathers and together they went to pay a visit to the Hoppo, or Chinese customs official54 in Macao. He met with him privately on several occasions and also protected him, going so far as to accommodate/shelter him in the palace for about a month when he was ill.

In turn, the city also displayed its support for the travellers. In no time at all, "[...] the Portuguese ladies undertook to provide the apparel for our female fellow travellers [...]," and, according to Benyowsky, "[...] the town made me a present of one thousand piastres in gold, with forty-two pieces of blue cloth, and twelve pieces of black satin."

Despite the warmth and care with which they were welcomed in Macao, twenty one of the Hungarians died in the territory, some of them from indigestion after having over-indulged themselves on their arrival. The Count mentions this fact:

"For the first day, my companions lodged in a public house, and the excess and avidity with which they devoured the bread and fresh provisions, which they were now supplied with, cost thirteen of them their lives. These died suddenly, and twenty-four others were seized with dangerous illnesss."

Aphanasia, the young Russian girl buried in St. Paul's Church, also died in Macao. It is unlikely that the stories of her dying of despair on discovering that Benyowsky was already married are true. According to the Count, she died three days after arriving in Macao. Other than indicating his sorrow at her death, the Count mentions his plans to marry her off to "[...] the young Popow, son of the Archimandrite, to whom I had given the surname of my family [as a means of] repaying her attachment." His wording is too vague to reach any conclusions about how intimate they were. He must certainly have wished to take her under his wing and include her, broadly speaking, in the family, proof of his paternalistic behaviour. His move to give his family name to the son of the Archimandrite — a religious figure who most probably served his domain — provides further evidence of this attitude.

Other than the occasional aside, the Count provides no description of the city of Macao, as Manuel Teixeira is quick to point out. Neither landscape nor social environment is recorded. Nor does there appear to be any surprise at the location of the city at the edge of China or its inhabitants. The only exception is his expressed desire to visit Beijing, a wish that makes him hesitate between travelling to the imperial capital or returning to Europe when the opportunity arises. In this regard he writes:

"I was in doubt with myself this day, whether I should go to Beijing. I was greatly affected; for I should have been exceedingly gratified with the view of the capital, and interior parts of the Chinese empire: and a favourable opportunity now presented itself; but to have embraced it, would have required me to abandon my project, and defer my return to Europe. It was not till after much deliberation, that I at last determined to give up my intention [...]."55

Despite this, he mixed not only with the Governor but also with several of the most important local residents and authorities. He visited the various monasteries, the Hoppo, and the Bp. of Metelopolis, Mgr. Le Bon56 who served as his adviser, guardian and go-between in his dealings with the French East India Company. He was also, obviously, in contact with Hiss, who was one of several people whom the Governor placed at his disposal. However, Benyowsky makes no mention of these people, how they lived and socialised, other than how they affected the interests of himself and his party. It is particularly strange that a European travelling in the late eighteenth century, during which the influence of the Enlightenment and the fascination with exoticism were so strongly felt, should have been so indifferent to his fellow man in Macao, Guangzhou and the surrounding areas. It is as if geographical information and the collection of specimens — including those of the human variety, as is reflected in his interest in his Japanese companion — was only of interest insofar, perhaps, as they could improve his profit margin.

As an indication of his perceived right to represent his party, we see all the concerns and gestures that confirm acceptance and recognition of his status. Right from the beginning he deals with the Governor and local authorities on an equal footing, be they Portuguese or Chinese, civil or religious. He sets himself up in dignified quarters ordering the members of his party, including the officers, to dress in red and white. Within his own party, he saw fit to punish, pardon, liberate or terminate the services of those whom he no longer felt able to trust as in the case of a certain Stephanow to be discussed below.

His status as a leader — at times markedly military in nature — is clear on their arrival in the gun salute they fire on passing the fort and the frigate anchored at the mouth of Macao's harbour. Benyowsky keeps his men armed although he hands over some weapons to the Governor, and he controls them with an iron hand as shall be seen. His men are subject to his authority, power and even his meting out of justice, a something he does whenever deemed necessary to resolving the various conflicts that arise in Macao, problems that he always describes as "conspiracies".

When he fell ill he transferred command to a trusted man, Crustiew and, most significantly, when the Chinese authorities began to question his presence in Macao he dispensed with the assistance of the Governor and negotiated directly with the Chinese.

Benyowsky's attitude in his journal reflects an authoritarian stance, calling on his status as a nobleman and military commander of a company (to quote him), both in his capacity as a representative and as a reflection of the military and paternalistic power with which he believed himself to be endowed. This very much fell in with the European standards of the day.

On the other hand, he took responsibility for the fate of his party, to the very end. It was he who decided to sail to Macao and he alone who was responsible for negotiating with the various companies. The final decision was taken exclusively by him but this also meant that he was responsible for meeting all undertakings. Nevertheless, there were odd occasion57 when decisions were taken — or, rather, authorised — after a meeting with his associates.

Various business ploys were suggested to the Count during his stay in Macao, including purchasing the information collected during his dangerous voyage across the Pacific which he later published in his Memoirs [...]. These were presented by agents of the various European companies operating in China. In exchange they offered gifts, money, return passages to Europe and even employment in their service. In the end, Benyowsky opted to negotiate with the French Company.

We know that he had already sold his sloop, the St. Peter and St. Paul, through the Leal Senado. He received one thousand and seventy taels for it58 and the Senate even suggested valuing his arms and buying them for "[...] a fair price [...]" in another attempt to assist him. It is not clear whether he actually did sell, although the Count writes that"[...] the Governor reserved to himself all the arms [...]." Using Fr. Zurita as a go-between, 59 Benyowsky arranged to sell the furs he had brought from Siberia.

But, let us now turn to the troubles caused by the Hungarians' stay in Macao.

Canton, Sancian, Ma - Kao — detail.

("CHINA as Surveyed by the Jesuit Mi∫sionariesbetween the Years 1708 † 1717 with Korea & the adjoining parts of Tartary ").

In: Cartografia de Macau através dos tempos [Catálogo da Exposição/Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, [p. n. n.] (Dia da Marinha), 1986, Estampa [Illustration] II.

Canton, Sancian, Ma - Kao — detail.

("CHINA as Surveyed by the Jesuit Mi∫sionariesbetween the Years 1708 † 1717 with Korea & the adjoining parts of Tartary ").

In: Cartografia de Macau através dos tempos [Catálogo da Exposição/Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, [p. n. n.] (Dia da Marinha), 1986, Estampa [Illustration] II.

§4. TROUBLES IN MACAO

We have little information as to the Count's relations with most of his associates prior to the voyage, if indeed he had any, the exception to this being Wyndbladth, his old companion, Andreas Masynski and Boleslaus Sipsky, also Polish members of the Confederacy of Bar, and some Russian political exiles also. We do not even know how fate brought them together on the adventure that took them from Kamchatka to Europe, it was unless the common purpose of escaping from exile. What is evident, however, is that a faction questioned his command both regularly and actively. The most vocal member of this faction was Stephanow who is always referred to as the Count's opponent and the instigator of attempts to steal information and the ship's log in Macao. Finally, Benyowsky did not allow him to accompany the party to Europe as a result of his mistrust of him. Because of this, on leaving he paid him "[...] four thousand piastres, with leave to go where he pleased. He immediately took part with the Hollanders, whose director, Mr. L'Heureux, expecting to derive some information from him concerning our voyage, received him, and sent him to Batavia."60

Benyowsky arrested him on several occasions, starting as early as their visit to Formosa, probably on the 11th of September, when he was forbidden to go on shore, because of his violent reaction to the Count's decision on departing from Formosa. The Count was already clearly distrustful of this member of his party. Shortly afterwards, on the 20th of September, he repeated his actions after Stephanow had formed a party which intended to submit a complaint to the Governor about the Count as soon as they arrived in Macao. Once in Macao, the Count released him after four days, after having received "[...] a formal apology [...]" from the miscreant.

The Count appears to have placed his trust in Crustiew, handing over command to him when he fell ill. On two occasions he charged him with travelling to Guangzhou carrying letters addressed to both the directors of the French Company and the Viceroy. He also appears to have trusted Sibaew and Kuzneczow, as well as those members of his party who informed him of the various attempts at betrayal made by Stephanow — joined later by Wyndbladth — and even took up arms to protect him.

What was it that occurred in Macao?

The Count was inclined from the very beginning towards assistance from the French East India Company, using Olivier Simon Le Bon, Bp. of Metelopolis as adviser and intermediary. He reached an agreement with the directors of the Company on the 29th of September.

The representatives of the other European Companies operating in Guangzhou and with offices in Macao also tried to engage the Count, visiting him with proposals which he regarded as self-interested and which he thus rejected. The Count thanked them but excused himself saying that he had already given a commitment to the French and arguing that, with respect to entering the service of the English Company,"[...] it did not appear to me to be so easy; because it was not only necessary that I should be assured of a superior station, but that in the meantime all my people should be provided for; and that our common lot, and the execution of several projects should be secured."

This response did not find grace with Gohr who "[...] took his leave in an affected manner [...]," attempting to make use of Stephanow — who had accompanied him on this occasion — to pursue the aims of the English Company. Three days later, other representatives of the English Company, Jackson and Beyz, returned "[...] to offer a present of fifteen thousand guineas [...] in consideration of my consigning my manuscripts, and entering into their service." In addition to this, the Company would "[...] grant a pension of four thousand pounds sterling, reversible to my children; and that they should settle on each officer a pension of one hundred pounds, and each associate thirty pounds."

The attempts by the English Company went even further. What happened next can be regarded as typical of the atmosphere in Macao at the time. Macao, it should be remembered, with its location at the gateway into China, was one of the most lucrative trading posts of the period where the major European powers had gained a foothold. Because of this, it is worth describing what ensued in some detail. The European Companies were particularly interested in the discovery of other places where they could establish new markets and as such they were prepared to make major concessions in order to obtain pioneering geographical information. This attitude meant that any new lead or information became the focus of major disputes leading to the kind of entangled intrigues that occurred in this case, a case that could almost be described as espionage.

Six days after the last meeting with the representatives of the English Company, the Count found out that there was a conspiracy against him led, obviously, by Stephanow "[...] who had engaged to deliver my journals and papers to the English, for the sum of five thousand pounds sterling." It was Kuzneczow who had informed him, providing "[...] a letter of Mr. Jackson's, wherein that merchant asserted that Messrs. Gohr, Hume, and Beg, were ready to pay the sum on the delivery of all my papers [...]" as proof. On discovering this, Benyowsky made haste to entrust his papers to the Bp. of Metelopolis, Mgr. Le Bon.

Some days later, on the 15th of November, he tried to solve the problem by calling a meeting of his men and informing them that "I was assured that a number among them were discontented with me [...]," and that he thus wished to dispense with their services:

"I thought proper to declare to them that all those who were desirous of seeking their fortune elsewhere, were at liberty to quit me; and that as they had all received a retribution at my hands at the island of Formosa, I thought myself acquitted from them."

It was precisely at this moment that the conflict boiled to a head:

"I had scarcely made an end, before Mr. Stephanow loaded me with invectives, and charged me with an intention of depriving the Company of their share of the advantages I was about to receive, from the knowledge I had acquired during the voyage; and that the moderation I had shewn at Formosa, in delivering my share of the presents of Prince Huapo, was merely a scheme to deprive them of greater advantages. He then excited the companions to throw off my authority, by assuring them that he would secure them a large fortune they instant they should determine to put my papers in his hands, and follow his party. He adds that when I understood that he was supported by Mr. Wyndbladth, my ancient Major, the companion of my exile, and my friend, I was incapable of setting bounds to my indignation, and could not avoid declaring that their proceedings were highly disgraceful; and to confound them, I displayed their secret projects to the company, and justified my words by shewing Mr. Jackson's letter, which convinced them that Messrs. Stephanow and Wyndbladth, under pretence of serving the company, were desirous of securing the five thousand pounds to their own use. They were highly irritated, and threatened them; but Mr. Stephanow preserved a party of eleven, with whom he went to my lodgings; and [...] he seized my box, in which he supposed my papers were deposited."

The climax of the incident, which involved the use of arms, occurred when Stephanow "[...] fired a pistol at me, which missed. In consequence of this attempt, I gave orders for seizing and keeping him in secure confinement."

The situation had become so serious that Benyowsky managed to gain the Governor's permission to imprison them in Mount Fort, or "castle" as he calls it. Later on he discovered that the specimens he had collected during the voyage had been removed by his opponents:

"Mr. Sibaew assured me, that the Jew had bought the whole for one thousand five hundred piastres; whereas the pearls alone which I had, were worth five times that sum."

This account indicates that the Hungarians had a far from peaceful stay in Macao as was probably true of many Europeans. The men who had remained loyal to the Count even organised an ambush against members of the English Company which ended up in their capturing and flogging a Jewish agent in the service of the British. The Jew was carrying papers which contained the proposals offered to the "traitors":

"1. That the English would pay to each associate one thousand piasters, in case they would serve the Company, and put my papers in his hands.

2. That in case the associates refused to take the English party, the company would arrest them by force, in the name of the Empress of Russia, to deliver them up.

3. That the Company would answer for obtaining the Empress's pardon for them, if they would determine to make a voyage to Japan, and the Aleuthes Islands."

If this was really the approach taken by the English Company (which Benyowsky doubted, regarding it rather as a plot conjured up by the Jew in conjunction with Stephanow), it provides an insight into the importance that the Count's interests had locally. It was even deemed acceptable for foreigners to be arrested in a foreign land, moreover while they were enjoying the protection of the city and the Governor as we have seen! The way in which it was done seems clearly to have been to call the situation to the attention of the Chinese authorities who would certainly have used the usual threats of cutting off food supplies as a way of exerting pressure on the local government. This is exactly what happened.

The Count, who in the meantime had fallen ill61 and accepted the hospitality of the Governor, writes that the Chinese had approached the Governor over the presence of the Hungarians in Macao "[...] because the English Directors had informed them, that I was a pirate, and deserter from the Russians; and that upon this information, the Governor or Viceroy of Canton, had required the Governor to deliver me up, or, at all events to make me depart immediately. For this reason he advised me to pretend that my illness still continued, until the time the French vessels should be ready to sail. From his embarrassment, I perceived he was apprehensive that he might find my affair troublesome to himself. I therefore begged him to remain neuter, and undertook to terminate the business with the Chinese myself."

This, in fact, was what he did.

But the most likely scenario is that the Governor, was not only being courteous by helping him and letting him stay in his own palace. He would probably have wished to accompany at first hand the events, intrigues and conflicts surrounding Maurice Benyowsky and his companions, fearing that they might evolve into something demanding greater Chinese intervention.

Now we should ask what was the stance of the other Companies.

Nothing that could be compared to that of the English Company which, according to Benyowsky, was imperious, aggressive and totally unscrupulous. After the English Company's first overtures in early October, the Dutch tried their hand. On the 4th of October, the Count received a letter from the Director of the Dutch Company, L'Heureux making similar proposals to that of the English and attaching "[...] a present of cloth, wine, beer, brandy, some provisions, and two thousand piastres. His letter and present were accompanied with the offer of a passage for me to Batavia, and the assurance that I should be received into the Company's service. "

Benyowsky was, once more, unwilling to commit himself: "But as he made the same proposal as the English, I refused the acceptance of his presents, except the liquors."

It seems that the Dutch did not pursue this contact although they did end up providing assistance to Benyowsky's main opponent, Stephanow, which is slightly odd in view of the fact that he had served the English so well.

The ultimate winners in this denouement turned out to be the French Company to which Benyowsky had committed himself within days of arriving in Macao although he does not indicate the benefits which derived from this.

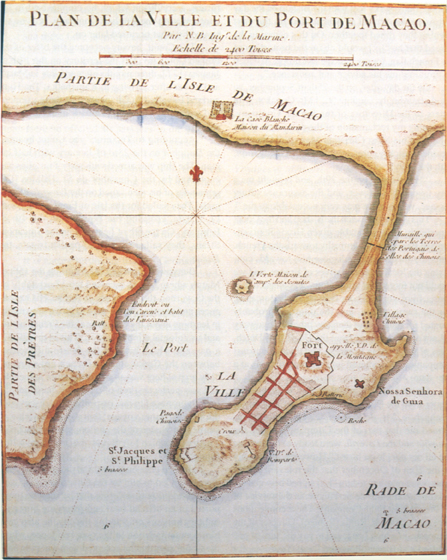

Carte de l'Entrée de la Rivière de Canton.

("Plan de la Ville et du Port de Macao.").

In: Cartografia de Macau através dos tempos [Catálogo da Exposição/Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, [p. n. n.] (Dia da Marinha), 1986, Estampa [Illustration] VI.

A reading of his Memoirs [...] indicates that the contacts were established by Mgr. Le Bon and it would be reasonable to suppose that Hiss, the interpreter appointed by the Governor, served as intermediary, including introducing him to the Bishop. Benyowsky met with the Bishop on the day following his arrival in Macao and on the next evening they dined together. On this occasion, he agreed that he "[...] would claim the protection of the French flag, for my passage to Europe, in which he promised me his advice and assistance."

On the day after, on the 25th of September, he acted accordingly, sending "[...] Mr. Crustiew with letters to the Directors of the French Company, containing my reclamation of the protection of the colours of his Most Christian Majesty." Crustiew returned quickly, presumably from Guangzhou, with the reply:

"He returned on the 29th, and brought me a very favourable answer, and the assurance of my passage, which news was very acceptable to me."

This affinity between the Bishop and the Count is perfectly understandable given Hiss's intervention and Benyowsky's empathy towards the French. Naturally this would predispose him towards contacting the local representatives of France, and we should not forget that this country was an enemy of Russia, from whose prisons Benyowsky had escaped. For the same reason, and the one that probably counted for much more than any other, Benyowsky did not opt for support from the English or Dutch, allies of the Russian Empress, and these countries' Companies only entered into the negotiations at a later date.

On the 12th of November, the Count received a letter from the Director of the French Company in Guangzhou, Mr. de Robien "[...] wherein he informed me that two of the Company's ships, the Dauphin and the Laverdi, were ready to receive me and all my people on board." However, it was only on the 20th of December that the relevant agreements were returned to him "[...] signed between me and the captain, Mr. de St. Hilaire, in the service of the French East India Company. These conventions were ratified by Mr. Robis [Robien], Director of the Company; in which I engaged to pay the sum of one hundred and fifteen thousand livres Tournois, for the passage of myself, and all my people."

That this contract implied a commitment between the Count and France to pursue projects in the future, a condition which he emphasised in his contacts with the English Company, will be revealed by what occurred later on.

The Count, having accepted the offer of the French Company, left the territory on the 14th of January 1772, three months after arriving in Macao and a year after arriving in Kamchatka. The Hungarians travelled to Guangzhou in three sampans and were only able to disembark in exchange for money.

According to Teixeira, 62 the Count boarded the Dauphin on the 23rd of January with half his men. The ship was armed with sixty-four guns and captained by the Chevalier de St. Hilaire. The remainder of his men sailed on the Laverdi, of fifty guns. They sailed for the Isle of France along with Fr. Zurita, crossing the Equator on the 4th of February. On the 6th of February, in the Singapore Straits, they sailed on with a Spanish frigate, the Pallas.

Benyowsky reached Mauritius on the 16th of March where he was received most hospitably by the Governor, the Chevalier de Roche. His experiences and meetings there were to prove very useful in learning about the character of the French nation and its colonial administration. This is revealed in a passage which hints at the future differences between the Count and the French government: "My arrival here was so much the more agreeable, as I was perfectly tired of the many questions the French proposed to me, respecting my discoveries during my former voyage: this voyage gave me an ample knowledge of the predominant character of a nation, to which I shall probably attach myself in future."

He then goes on to describe the courtesies that were extended to him by the Governor.

In addition to ordering that he shall be transported in an official boat and receiving him with military honours on entering the city, he also gave him accommodation in his own residence, which the Count says that he accepted with a certain selfinterest, hoping that his influence might be useful in future contacts with the French Court and Ministry.

On the very next day, however, after having visited an island in the company of the Governor, he notes his disagreement with French colonial policy: "[...] and these little journeys made me acquainted with some of the interests of French government, though I could never agree to call this establishment a colony. For the Isle of France can never be made any thing more than a military post."

From Mauritius he travelled to Fort-Dauphin (which fascinated him) reaching France by June. Here he offered his services to the government to establish a Colony on Madagascar63 — planned by the French since 1642 (under the mandate of Cardinal Richelieu, who founded Fort Dauphin in the following year) [sic] which only became effective rulers of the island from 1895 to 1960 —, as is well known, where he died on the battlefield in May 1786. He was only forty years old; his life had been filled with adventure and constant upheaval.

It is hardly surprising that the German playwright August von Kotzebue64 should have recorded his character in Die Verschwörung aut Kamtschatka (The Kamchatka Conspiracy), 65writing a verse novel on Benyowsky and his loyal companion Pal Ronto66 and that he should have become quite a popular hero in the central European countries where we know that he had inspired a movie and several works even in the field of children's literature.

Benyowsky's biographers67 are not in agreement as to his character which is hardly surprising in the face of such a controversial personality and one whose life has been little studied, particularly the period he spent in Macao and South Asia. They all recognise his bravery and daring but some (Lesseps and Rochon) regard him as a perfidious, cruel tyrant and even an impostor68 or a visionary (Davidson) while others (Wadstrom) exalt his noble generous character suggesting that his memory should be rehabilitated.

The evidence lives on in the Count's muchdisputed Voyages et Mémoires [...] (Memoirs [...]), written in French. Three years after his death, in December 1789, the original text was translated into English and published69 London by the mathematician and chemist William Nicholson under the title The Memoirs and Travels of Mauritius Augustus Count de Benyowsky, Magnate of the kingdoms of Hungary and Poland, one of the chiefs of the Confederation of Poland, &, &, Written by himself. Translated from the Original Manuscript. It has not been possible to find out how he gained access to the manuscript, which it seems eventually fell into British hands. Similarly, it has not been possible to find out if the period covered in the journal lasts from 1747 to 1786. 70

Between 1790 and 1792, the two volumes of the French version were published under the title Voyages et Mémoires de Maurice-Auguste, Comte de Beniowsky, Magnat des Royaumes d'Hongrie et de Pologne, son exil au Kamtchatka, son evasion, et les détails de l'establissement qu'il fut chargé par le Ministre François de former à Madagascar. 71 They were the subject of the following comment by Feller: "[...] ne sont à beaucoup d'égards qu'un roman, où il est difficile de distinguer les faits réels de ce qui est purement le fruit de l'imagination."("[...] they seemed to several people no more than a novel where it is difficult to separate reality from the imagination."). 72

Fact or fantasy, this is still an interesting document, of which there are several versions in other European languages such as Polish, Hungarian and German. 73 It records one man's path through life while reflecting some of the uncertainties of the period and, particularly with regard to Macao, it is an example of one of the many individual paths that crossed in the territory in search of the famous, exciting trade in China that attracted (and consumed) so many nations, interests and people. ***

Translated from the Portuguese by: Marie Macleod.

NOTES

** Town Council.

*** This article is a reformation of two papers presented at the FOURTEENTH CONFERENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF HISTORIANS OF ASIA, Bangkok, Chulalongkorn University, 20-24 May 1996, as a representative of the Cultural Institute of Macau, and in the 35th ICANAS, Budapest, Budapest University of Economics, 7-12 July 1997, where the author went with the support of Fundação Macau (Macao Foundation), the Instituto Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macao) and the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation).

1 JORGE, Cecília - COELHO, Beltrão, Viagem por Macau. Comentários, Descrições e Relatos de Autores Estrangeiros (Séculos XVII a XIX), 2 vols., Macau, Governo de Macau / Gabinete do Secretário-Adjunto Para a Comunicação, Cultura e Turismo - Livros do Oriente, 1997, vol. 1.

2 According to Account of an Extraordinary Adventure in a letter from Canton, in "The Annual Register", London, 1772; apud TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Maurício Benyowsky, in "Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões", Macau, 1 (2), Março [March] 1966, pp. 129-147, p. 136

3 PEREIRA, João Feliciano Marques, A Gruta de Camões: Impressões e reminiscências, "Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo: 《大西洋国》 Arquivos e Annaes do Extremo-Oriente", 4 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação Cultural -Arquivo Histórico de Macau, 1984 [1st edition: Lisboa, Antiga Casa Bertrand-José Bastos, Livreiro-Editor; facsimile 2nd edition: — 1889-1900; facsimile 3rd edition: 3 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação e Juventude - Fundação Macau, 1995 — 1863-1866 and 1889-1900], vols. 3-4, pp. 30-38, 84-91, 383-391, pp. 85- 91.

4 DAVIDSON, James W., The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. History, People, Resources, and Commercial Prospects. Tea, Camphor, Sugar, Gold, Coal, Sulphur, Economical Plants, and Other Productions. By James W. Davidson, Taipei, SMC Publishing Inc., 1992, p.84 — The author mentions the Loo-choo archipelago.

5 IMBAULT-HUART, L'Ile Formose. Histoire et Description par Imbault-Huart, Taipei, SMC Publishing Inc., 1995, p. 111.

6 Which he did in an extremely violent manner, if we trust both, IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p. 112, and especially, DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., p.85.

7 DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., pp. 84-85.

8 IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p. 112 — The author describes him: "Il avait un chapeau galonné sur la tête, un sabre pendait à son côté; ses bas étaient d'éttofe et ses souliers devaient avoir été frabiqués par lui-même [...]." ("He was wearing a galloned hat, one sabre; his breeches were made of stuff and his shoes should have been made by himself [...].").

9 DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit.

10 Ibidem., p.85

11 Ibidem., p.86 — According with Don Hieronimo he was: "[...] one of the independent chiefs of the country[...]; that his residence was about thirty miles inland; that he was much annoyed by Chinese on the west; and that his central territories were civilized, but that the eastern coast, excepting of course Huapo's division, was possessed by savages."

12 Who had ruled Formosa since 1683. It became a prefecture of Fujian province, but there are several reports of frequent rebellion against the Chinese, mostly in the Western districts where Koxinga's followers' descendants were located.

See: DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., pp. 63-101.

13 IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p. 112 — According to the author: "Les coalisés marchèrent sur le village inhospitalier, massacrèrent plus de mille ennemis et brûlèrent toutes les maisons." ("The confederate attacked the inhospitable village, exterminating more than one thousand enemies and firing on all the houses.").

See: DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., pp. 84-86 — The author agrees with that violent description but shows also some humanity in the Count's behaviour: "Benyowsky now declared that he would fire on his own party if they continued the massacre longer."

14 Ibidem., p.88— Benyowsky describes him as: "A native chief allied and tributary to the Chinese, had demanded that Huapo should punish with death several of his subjects on account of certain private quarrels: but [...] Huapo, instead of acceding to the request, made an unsuccessful war against Hapuasingo, and was compelled to pay him a considerable sum as an indemnity; [...] the Chinese governor, under the pretence of obtaining further reimbursement for his expenses, had in conjunction with Hapuasingo seized one of his finest districts; [...] his [...] capital was not more than a day and a half's march distant; [...] his army did not exceed 6,000 men while the Chinese were about 1,000 with fifty muskets [...]."

15 IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p. 115.

See: DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., p.87 — The author confirms: "[...] he [Benyowsky], therefore, offered to aid him to the full extent of his power in carrying out his design of liberating the island. "This beginning", says Benyowsky, "and the representation of Don Hieronimo that I was in fact a great prince, insensibly led me to play a new part, as though I had visited Formosa for the purpose of satisfying myself concerning the position of the Chinese and of fulfilling the wishes of the inhabitants by delivering them from the power of that treacherous people." The count was, indeed, no stickler for the right, whenever he could gain his ends by playing a new or a double part."

16 Idem.

17 Idem.

18 DAVIDSON, William J., op. cit., pp. 87-88.

19 Idem. According to Benywosky: "We approached a small fire, upon which we threw several pieces of wood. A censer was then given to me and another to him. These were filled with lighted wood, upon which we threw incense, and turning towards the east, we made several fumigrations. After this ceremony the general read the proposals and my answers, and whenever he paused, we turned towards the east and repeated the fumigation. At the end of the reading the prince pronounced imprecations and maledictions upon him who should break the treaty of friendship between us, and Don Hieronimo directed me to do the same, and afterwards interpreted my words. After this we threw our fire on the ground and thrust our sabres in the earth up to the hilts.

Assistants immediately brought a quantity of large stones, with which they covered our arms: and the prince then embraced me and declared that he acknowledged me as his brother [...]."

20 IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p. 116.

See: DAVIDSON, James W. op. cit., p.89 — The author points to the same description.

21 IMBAULT-HUART, op. cit., p.116.

22 Idem.

23 DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., p.89.

24 Ibidem., p.87

25 Ibidem., p.89.

26 Ibidem., p.87

27 Ibidem., pp. 89-90 — "It is extremely doubtful whether the aborigines were in possession of horses. Travellers on the East coast, at least, have not met with roads made by the aborigines which struck them as suitable for cavalry, nor have they known of the Formosan savage who possessed either gold or silver, especially, the latter, in large quantity, or even pearls, although some rubies have been seen. But as the author was no doubt inclined to give a favorable aspect to his proposed enterprise of colonizing the island, the gold, silver, and pearls were probably included as a relish to his description."

28 Ibidem., p.89.

29 PEREIRA, João Feliciano Marques, op. cit., p.86 — The author confirms that Benyowsky: "[...] was able to persuade the local indigenous of the advantages of European colonization and that, once in France, he had even tried to promote the Formosa project."

30 DAVIDSON, James W., op. cit., pp. 89-90 — The author remarks: "In Europe, however, Benyowsky's scheme was considered to be rather a visionary one. This was no doubt due to the fact that the rewards promised were greater than any careful statesman would be inclined to believe possible [...]," also warning the reader as to the fidelity of Benyowsky's descriptions: "In conclusion we would say that we have quoted from this curious book, rather because it speaks of a subject otherwise quite unknown than because it is of undoubted veracity in all its statements."

31 Ibidem., p.90.

32 TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Benyowsky em Macau e Count de Benyowszky: A Hungarian Crusoe in Asia, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1966, pp. 21-34.

33 Piastra = Silver coin whose value varied depending on where it was used.

See: PEREIRA, João Feliciano Marques, Uma resurreição historica, in "Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo: 《大西洋国》 Arquivos e Annaes do Extremo-Oriente", 4 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação Cultural - Arquivo Histórico de Macau, 1984 [1st edition: Lisboa, Antiga Casa Bertrand-José Bastos, Livreiro-Editor; fac-simile 2nd edition: — 1889-1900; fac-simile 3rd edition: 3 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação e Juventude - Fundação Macau, 1995 — 1863-1866 and 1889-1900], vols. 1-2, pp. 31-41, 113-119,181-188, p.39—The author places silver coin value at that of the Spanish Pataca, adding that in the nineteenth century it had fallen into disuse, replaced by the Mexican Pataca.

34 This Portuguese was a simplified, non-uniform form of the mother tongue mixed with other languages of the region, primarily Malay and those of the Indian subcontinent, particularly from the coastal regions, such as Gujarati, Maratha and Konkani. Being a language of a maritime network, that Portuguese was used from the sixteenth to the ninetenth centuries throughout the Orient as a new lingua franca, replacing in some regions the Malaio, the previously used one by the pilots sailing the Indian and Pacific Ocean.

Portuguese was used to write the official documents used in contacts between the various Eastern peoples and Westerners. It was also used for communications between different Europeans such as the Dutch, British, Danish and Spanish over a geographical area spreading from India to the Mauritius, Sumatra to Japan, Batavia to Sri Lanka, the Celebes to Nicobar and even China, as well as present-day Thailand and Burma. This linguistic contact led to the introduction of countless Portuguese words in Oriental languages (and vice-versa), particularly in Japanese and Malay, which reflect of the kind of relations established.

35 TEIXEIRA, Manuel, op. cit., p.21 — According to Benyowsky: "Tanajou" [sic]. According to Teixeira: "Tanasoa".

From the latitude given and the number of sailing days from Macao, this may have been the harbour at Ti-Li-Soa (Ty Lo So) or Ta-pong-song, otherwise known as Beias, or Bias Bay. "Hopching" may have been Ping-Hay-Soa or "Harlem Bay" in English charts.

36 TEIXEIRA, Manuel, op. cit., p.47.

37 See: XU Xin, Macao and the Tributaries Scroll of the Qianlong Emperor, in "Review of Culture", Macau, ser. 2 (23) April-June 1995, pp. 25-32.

38 For the same reason, we are moved to transcribe the description of Hungarians that appears in the abovementioned Tributaries Scroll, an exceptionally interesting document.

See: The Tributaries Scroll of the Qianlong Emperor, in "Review of Culture", Macau, 2nd series, (23) April/June 1995, pp. 33-55, p.38 (text) [and p.39 (illustration)] —

"Hungarian Man

Hungarian Woman

Hungary is South of Bosnia. The Hungarians look like the Mongols. They usually dress in short vests and trousers, close-fitting, to their legs. They are inteligent and courteous. Expert horse riders, their short necked horses are extremely fast. They usually carry daggers 4 chi long. They cavort their horses, and whenever they ride [them] they spin and turn brandishing curved swords 4 chi long. The women know how to read and write, and are experts at making embroidery. They must cover themselves with a veil when going out. It is an extremely plentiful country, particularly in minerals, being unexhaustive in their gold, silver, copper and iron deposits. They are so many cows and sheep, that they export abroad much of their cattle." Also see: Ibidem., pp. 40-41 — For an equally fascinating description of the Poles (p.40) and the accompanying illustration (p.41) of a bear in chains, given that "At home, they raise up bears both to eat, and for ammusement."

39 As they are commonly known.

See: NUNES, Isabel, The Singing and Dancing Girls of Macau. Aspects of Prostitution in Macau, in "Review of Culture", Macau, 2nd series, (18) January/March 1994, pp. 61-84 — The author emphasises that the association between the flower world and prostitution is not an exclusively Oriental phenomenon. She writes (p.70) that despite the lack of documentation on the subject, this tradition seems to date back to the reign of Liu Ch'ao, Emperor during the Six Dynasties (265-589),, and lasted in Guangdong until the Cultural Revolution. It was divided into two types of activity, "[...] on the basis of the kind of boat or the kind of surroundings."

Benyowsky provides no details that give any insight into which of the two kinds of boat might have been visited by his men. Nevertheless, it is a succinct record of one typical feature of the South China Seas, noted not only by this traveller but also by many other Europeans, some of whom give more details.

40 See: NEEDHAM, Joseph, Science and Civilization in China, 8 vols. [cont.], Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1954-1996, vol. 4, part. 3, 1971, pp. 225-227,310 — For more on the importance of China's tributary policy in maintaining the status quo and developing domestic communications — the construction of the Grand Canal from the Sui dynasty (AD 581-618) to the Yuan (1279-1368) being the greatest undertaking in this direction; ibidem., p. 487 ff. — For information on China's foreign policy.

Also see: PTAK, Roderich, China and Portugal at Sea. The Early Ming Trading System and the Estado da India Compared, in "Review of Culture", Macau, (13/14) January/July 1991, pp. 21-38; BLUSSÉ, Leonard - ZHUANG Guoto, Fuchienese Commercial Expansion into the Nanyang as Mirrored in the Tung Hsi Yang K'ao, in "Review of Culture", Macau, (13/14) January/July 1991, pp. 140- 149.

41 Islands in the South China Sea, thus named because it was there that pirates sought shelter. They are located to the Southeast of Macao at the mouth of the Pearl River: Port.: Ladrone Grande (Lao Wan Shan), and Port.: Ladrone Pequeno (Pocking Shan). They also appear under the name "Yong-ngao".

See: PEREIRA, João Feliciano Marques, Uma resurreição [...], 1984, op. cit., pp. 119; PEREIRA, João Feliciano Marques, A questão do Extremo-Oriente e o papel de Portugal no "desconcerto" Europeu, in "Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo: 《大西洋国》 Arquivos e Annaes do Extremo-Oriente", 4 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação Cultural - Arquivo Histórico de Macau, 1984 [1st edition: Lisboa, Antiga Casa Bertrand-José Bastos, Livreiro-Editor; fac-simile 2nd edition: — 1889-1900; fac-simile 3rd edition: 3 vols., Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação e Juventude - Fundação Macau, 1995 — 1863-1866 and 1889-1900], vols. 1-2, 587-595, 639-654, p.640.

42 The medicinal properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) have been known since Antiquity, in the West as well, as a treatment for stomach complaints and violent fevers. It was even used as a precaution against the plague. The aphrodisiac properties of the same root-stock have also been highlighted for a long time.

43 PIRES, Benjamim Videira, A Vida Marítima de Macau no Século XVIII, Instituto Cultural de Macau - Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1963, p.106 — "The seventeenth expedition was that of the "corvette" St. Peter and St. Paul, in which I had the good fortune to quit Kamchatka on the 12th of May, 1771, and arrived at Macao on the 22nd of September in the same year".

Benjamim Videira Pires and Benyowsky both refer to the ship as a "corvette":

44 OLEIRO, Manuel Bairrão, Notas Sobre o Comércio Marítimo de Macau nos Finais do Século XVIII, in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, (13/14) Janeiro/Junho (January/June) 1991, pp. 96-104, pp. 97-100.

45 Picul = Measurement of weight used in the Orient which varied but could be divided into catties and taels. Each picul usually had one hundred catties (kan). It generally weighed between 60.453 and 60.471 kilograms. Each catty consists of 16 taels, or around 630 grams, making a kilo something between 1 catty and ten taels.

See: Note 46.

46 See: "Arquivos de Macau", Macau, 3rd series, 4(1) Julho (July) 1965, p.43 — For a reliable transcription of the Record concerning the "Hungarians", included in the Livro de Termos dos Conselhos Gerais do Leal Senado (1752-1786), fol. 56 held in the Arquivo Histórico de Macau (Historical Archive of Macao).

47 NO

48 See: 0 SENA, Tereza, A Questão da Entrada de Estrangeiros em Macau nos Finais do Século XVIII, in SEMINÁRIO INTERNACIONAL DAS RELAÇÕES LUSO-CHINESAS: "TEMAS E PROBLEMAS DA HISTÓRIA LUSO-CHINESA. O ESTADO DA QUESTÃO" (INTERNATIONAL SEMINAR ON SINO-PORTUGUESE RELATIONS: "PROBLEMS AND ISSUES OF THE SINO-PORTUGUESE HISTORY. CURRENT ASSESSMENT"), to be held in Macao this coming October.

49 JESUS, Montalto de, Macau Histórico, Macau, Livros do Oriente, 1990, pp. 109-117; JESUS, Montalto de, Historic Macao, Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 1984, pp. 124-137 [2nd edition: Macau, Salesian Printing Press - Tipografia Mercantil, 1926].

50 In fact this was no more than a systematic presentation of the regulations which already existed. As far as concerns this research, they restricted the presence of foreigners on Imperial territory to the duration of the trading season and disallowed the presence of women.

In broad terms, the following rules were also made:

— Ships had to remove all their weapons prior to entering the port of Guangzhou;

— All business had to be completed by the close of the season, free from debts and credits until the next season;

— All business had to be conducted through the Co-Hongs — a corporation of Chinese traders expressly set up for this purpose in around 1720;

— Foreigners were forced to remain in their factories and could only walk out in very limited areas and times. They were not allowed to enter the city of Guangzhou.

51 By "foreigners" and "foreign countries", I mean with Western countries and obviously not those Asian countries with which China had maintained relations over centuries under its tributary system.

52 HUNTER, William C., Bits of Old China, Shangai, 1886, p. 156; apud BRAGA, José Pedro, The Portuguese in Hongkong and China. Their Beginning, Settlement and Progress during One Hundred Years, Offprint "Renascimento", Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1945, p.60.

53 SOUZA, George Bryan de, A Sobrevivência do Império: Os Portugueses na China (1630-1754), Lisboa, Publicações Dom Quixote, 1991, pp. 263, 262; SOUZA, George Bryan de, The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630-1754, London, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

54 The term "Hoppo" was a bastardisation of 'Hó-p'ó so' or 'Hai kuan pu' [Hepo] and was the name commonly used for the Chinese official at the head of the Maritime Customs at the port of Macao which existed from ca 1684 (on the excuse of preventing large ships sailing up as far as Guangzhou) until 1849.

55 TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Benyowsky em Macau [...], 1966, op. cit., p.14.

56 Oliver Simon Le Bon (°1710-†1780), a Frenchman who left his country in 1745 to join the Siam Mission. In 1754 he was appointed Procurator of the Paris Foreign Mission in Macao and in 1764 titular Bishop of Metelopolis and Coadjutor of Siam.

See: TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Benyowsky em Macau [...], 1966, op. cit., pp. 25, 29; TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Maurício Benyowsky [...], 1966, op. cit., pp. 138-139), — According to the author he would have been in Macao at the time of his way back to his Mission in Siam.

57 On Formosa as mentioned above.

See: TEIXEIRA, Manuel, O Conde Benyowsky em Macau [...], 1966, op. cit., p.45 — On one occasion when Stephanow seems to have wished to go ashore; ibidem., p.58 — And in Macao on the 10th of December when Benywosky says: "I assembled all my companions, and proposed to them to embark on board the French ships, in order to return to Europe [...]," although he had in fact taken this decision in September, "[...] they consented, and submitted entirely to my orders."