[INTRODUCTION]

In Imperial China's state cult system the granting of titles and ranks to those deities who had been admitted to and integrated into the state cult pantheon formed an essential expression-form of the communication between this worldly and the otherworldly, between the spheres of the human and the divine. These bestowments - by means of which the state could differentiate among deities worth regard to its appreciation of their abilities, importance and efficacy - are recorded, e. g., in the texts of official Imperial Decrees and Proclamations on special occasions. These and other measures of the state were jointly characterized by the principles of reward and encouragement. 1

The diversity of these titles and ranks provides a vivid impression of the state-cultic careers of Chinese deities. In this context it becomes conspicuous that not all of the titles' contents are merely describing abstract values and general virtues. Instead, some also seem to relate to more concrete occurrences. There arises the question whether the overall historical development of such titles was stereotyped and mechanical or whether connections can be confirmed between the more 'individual parts of longer titles' (Titulaturen) and the historical occurrences on which their bestowment had depended upon.

Below I will consider this question, taking the titles of the Chinese female deity Mazu as an example. In the state cultic context Mazu is well-known under several other, more 'official' names, e. g., Tianfei• (Heavenly Princess), Tianhou• (Heavenly Empress), or Tianshang shengmu• (Holy Mother in Heaven). 2

As a textual source I will use the Tianfei xiansheng lu• (The Records of the Manifested Holiness of the Heavenly Princess - hereafter TF). This officious compilation contains the well-known legend of the famous deity as well as a representative collection of documents concerning Tianfei. 3 These documents are preserved in the following two sections of the TF: Lichao xiansheng baofeng gong ershisi ming• (The Complete Twenty-Four Decrees on the Occasions of Granting of Honorific Titles Due to Manifestations Throughout the Successive Dynasties) (TF, pp. 1-2), and Lichao baofeng zhiji zhaogao• (The Imperial Proclamations of Honorific Bestowments and Ordered Sacrifices Throughout the Successive Dynasties) (TF, pp. 3-16). Comparisons with other relevant sources, e. g., the dynastic histories, have been made but will, due to limitations of space, not be dealt with here.

PREVIOUS PAGE.

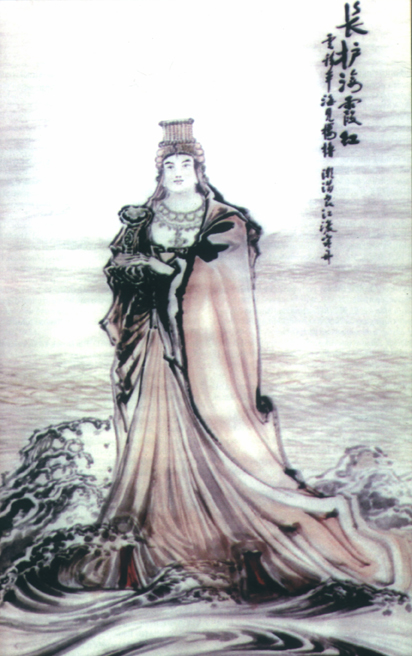

Ama, Godess of the Sea[Tianfei天妃].

YAN JINHUA 顏金華

1996. Coloured inks on rice paper. 28.8 cm x 46.4 cm.

PREVIOUS PAGE.

Ama, Godess of the Sea[Tianfei天妃].

YAN JINHUA 顏金華

1996. Coloured inks on rice paper. 28.8 cm x 46.4 cm.

§1. THE STATE AND THE REALM OF THE GODS: THE RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

In Chinese, polytheism, the divine personae of the pantheon are specified according to their individual competencies and supernatural efficacy (ling), even though this does not totally exclude overlapping. They represent a parallel as well as hierarchically structured order. A relative movement of individual deities within this structure obviously seems to point to an underlying specific development which can be expressed in terms of gain or loss of importance and meaning.

Knowledge of the supernatural competence of a deity is of vital help to the human petitioner in deciding which deity to turn to with a particular request in order to receive the most effective help or response.

Within the Chinese cult system, however, it is not the individual but the state - that is, its representatives - that performs before the deity. And the response of the deity does not apply to the individual problem or a single worshipper but refers to the need of the state.

The anthropomorphism of the deities is instrumental in the effective functioning of this model of communication with the divine realm. And, in the case of China, we can add to this the structuring of the realm of the deities as a hierarchy which is parallel to the mundane world with its offices and officials. Thereby the connection between state and pantheon - as well as that of the proxy petitioner, i. e., the official, with the respective deities in charge - cult be conceptualized in a way which, in principle, transferred and transformed the immanent structure into the sphere of the transcendental.

The state transferred the modes of this-worldly bureaucratic communication into the divine world. In analogy, it could thus promote or degrade deities and extend their competencies by means of official recognition, the bestowment of titles and ranks, and the like, as is well-known. 4 This kind of communication was construed as a dialogue and the reciprocal co-operation according to the principle of xuyuan, comparable to the ancient Roman do ut des.

The cult system (i. e., in those instances that were of special interest to the compilers of the TF and therefore included in the text) the state instead of the individual performs. The respective competence and supernatural usefulness of a certain deity, its effectiveness and efficacy as well as the formerly proven and henceforth expected response are the coordinates for careful deliberation. That notwithstanding, many of the formulations and phrasings of imperial proclamations leave us with the impression that the performer of sacrifices, offerings, and proclamations was very acutely aware of his own indispensability for the deity receiving them. 5

The Emperor, being the Son of Heaven, is occupying the highest position in representing the state in fulfillment of cultic activities, presenting offerings, etc. As the supreme mediator, his position is hierarchically below heaven indeed, but still well above man - and deity. 6 His granting titles and honours to deities bind them to the state and at the same time both stresses and helps to advance their loyalty and divine willingness to care about the state's concerns and interests. A deity's 'co-operation' with the state effects - respectively, confirms - its orthodox status of official recognition and legitimacy. At the same time this diminishes the potential danger the state traditionally (and often, with good reasons) attributed and, to some extent, still does attribute even nowadays to all heterodox folk religious cults that thus far lack official recognition. 7 An integration could put an end to this insecurity for the state, while a particular cult no longer had to be forbidden, fought, and subdued. 8 Besides, officials who promoted official recognition of local cults by means of submitting Memoranda to the throne, etc. could thereby give tokens of their own - as well as their real of administration's - reliability and loyalty. To be supporting of temple cults was advantageous to officials not only in abstract terms but also by yelding more concrete benefits.

§2. THE TITLES: CONCEPTION AND FUNCTION

The essential individual title-parts [or 'individual parts of longer 'titles' (Titularen)] (i. e., two Chinese characters each) and the rank of a deity taken together form what will be termed 'titles' (Titulatur) here. These elements can be differentiated according to quantity (i. e., title-parts) and quality (ranks). The titles are a distinguishing attribute of a deity and their development and growth describes its state cultic career. They give evidence of both the historical continuity and quality of a deity within the state cult system, and they are an expression of the public orthodox integration of its cult.

The titles, the parts of which fulfill the function of epithetae ornantiae, render the deity, i. e., its divine competencies and abilities, namable and susceptible for the adorant; at the same time they define the deity buy limiting it. 9 In accordance with the anthropomorphism in Chinese religion the deity, to a certain extent, becomes limited, 'finite', since even the longest accumulation of titles is a limited enumeration of attributes. 10 Taking the growth and development of the titles of Tianfei as an example. there arises, for instance, the question whether it would be tenable in this context to speak of a "[...] confinement by means of extension [...]."

All title-parts can be distinguished by their Chinese characters but, with regard to their contents, many of them are either similar and redundant. But there are also titles which allude to special abilities or competencies attributed to a particular deity, titles that highlight certain characteristics. The question remains whether the combined contents of individual titles also individualizes a deity unambiguously or not.

The state cult was construed as expressing a kind of relationship between two freely acting parties. It insinuated that the deity also played an independently acting and active role of its own. This construction at the same time provided the state with the opportunity to impinge upon hitherto purely folk religious cults whenever deemed necessary. In doing so, however, the state seemed less intent on an integration of heterodox values with regard to cultic content or a reformulation of content rather than a formal absorption, 11 which might be termed 'absorption by means of integration'.

Considering these factors according to quantity and quality by taking the Tianfei-titles as an example is consequently closely connected with an evaluation of this particular deity's 'career' which in turn relates to Tianfei's efficacy in devoting herself to the state and its interests. The accumulated length of her titles demonstrates her extraordinary significance within the state cult system. Tracing them through the course of history, we may also gain, in tendency, an impression of the developments and changes in the relationship between state and deity, between this world and the other world.

§3. THE TIANFEI-TITLES

3.1. GENERAL SURVEY

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, before the termination of the Chinese Empire and, along with it, of the state cult system, the complete accumulated titles of the goddess Tianfei read:

"Huguo bimin miaoling zhaoying hongren puji fuyou qunsheng chenggan xianfu xianshen zanshun chuici duhu anlan liyun zetan haiyu tianpo xuanhui daoliu yanqing jingyang xizhi enzhou depu weicao baotai zhenwu suijiang jiayou Tianhou zhi shen"

“护国庇民妙灵昭应宏仁普济福佑群生诚感咸孚显神赞顺垂慈笃祜安澜利运泽覃海宇恬波宣惠导流衍庆情洋锡祉恩周德溥卫漕保泰振武绥疆嘉佑天后之神”

("Goddess Heavenly Empress Who Watches Over the Country and Cares for the People, Who is of Miraculous Efficacy and Clear Responsiveness, Great Humanity and All-Encompassing Assistance and Fortunate Helper of the Masses, Whose Sincere Feelings are Absolutely Credible, Who is Manifested Godliness and Supportive Complaisance, Yielding Leniency and Magnanimous Blessings, Who Calms the Billows and Thereby Renders Services to Transports, Whose Favours Extends All Over the Maritime Regions, Who Dwarfs the Waves and Thereby Shows Her Mercy, Who Directs the Currents and Thereby Spreads Good Fortune, Who Pacifies the Ocean and Thereby Confers Blissfulness, Whose Favour and Graciousness are Widely Dispersed, Who Safeguards the Transports at Sea and Secures Peace, Who Incites Combativeness and Pacifies the Sovereign Territory, and Provides Excellent Assistance"). 12

These titles comprise sixty-six Chinese characters, sixty-two of which are individual titleparts. As a whole (Titulatur), they represent the climax of a development that had started already in the early twelfth century (AD 1122) with the beginning of the state cultic career of the goddess. But even before the state paid attention to the late Tianfei, she had already gained a substantial popularity as the patron goddess of the inhabitants of the south Chinese coastal regions, and her supernatural activities showed a close connection with the maritime surroundings of those areas. 13

The first section of the TF, The Complete Twenty-Four Decrees on the Occasions of the Granting of Honorific Titles Due to Manifestations Throughout the Successive Dynasties (pp. 1-2), gives a good impression of the beginnings and development of the Tianfei-titles. Here we find listed twenty-four different honours conferred upon the deity between the years 1122 and 1684. Of these, seven are registered without further mentioning individual occasions but with general allusions to Tianfei's godly help and fulfilled omina. As for the other honours, we can attest the following reasons for their conferment: protection during (envoy-) travel of a state official (three times); protection and fighting against bandits and pirates (six times); help during drought and famine (three times); general protection of country and people (one time); protection for grain/rice transports by water (five times, all during the Yuan dynasty). A concrete name of the place where the honours were bestowed in a local temple of the goddess is mentioned eight times; the name of a protagonist, in each case an official, is mentioned four times.

The second section of the TF, The Imperial Proclamations of Honorific Bestowments and Ordered Sacrifices Throughout the Successive Dynasties (pp. 3-16), starts its report sixty-eight years later than the first section but is more detailed and covers a longer period of time, the years between 1190 and 1727.

The last part of the TF (pp. 17-46) gives the legend of Tianfei in fifty-four episodes which start with introducing her parents and family, give the story of her miraculous birth, and tell about her supernatural feats, first as a human being, the girl Lin Moniang,• and later, after her apotheosis, as a deity.

3.2. SONG

In Song• times (960-1279), the miracle-working of the young goddess, shortly after the apotheosis of Lin Moniang (presumably 960-987), is still quite unspecified. Many dream revelations of the goddess to common people are described in the legendary episodes of the TF (pp. 17-46), as well as minor magical 'conjuring-tricks'; but we can also read about the elimination of droughts or the termination of an excess of rain.

With regard to the admission of Tianfei into the state cult system, it was of vital importance that the people who believed in her and who, by means of official Memoranda, brought to the notice of the emperor their personal miraculous experiences - for example, their being saved from a tempest, or her divine responses to their implorations in times of extreme distress - were 'official' persons, i. e., civil servants, state-officials, eunuchs, ambassadors, etc. Upon receipt of such Memoranda via the official procedure, the Emperor could bestow honours upon the deity. A belief in Tianfei and, simultaneously, an official position, an incumbency, were necessary for the petitioner to be able to officially communicate the miraculous feats to the Emperor. 14

In the beginning these forms of 'testimony' were relatively scarce and the TF duly reflects this situation: state-officials as recipients of her assistance are mentioned only in TF episodes nos. (10), (14), and (16). In this respect, peasants, fishermen or merchants were not counted among the representatives of state orthodoxy. 15

In general, there is no special profile of the goddess discernible which would hint at her usefulness to the state in the Song-time episodes of the TF and the honours registered in the text are relatively common ones. In the first place, the legend illustrates the workings of the goddess while still in her human, pre-apotheosis, form, when there was not yet a goddess Tianfei and the state cult system had not yet started paying attention to her. Her significance during this period of time was still limited to the popular and regional levels. 16

In the case of Tianfei, as the TF tells us, the initial announcement to the throne of her divine help happened after the official Lu Yundi in 1122, upon having running into distress at sea on a legendary journey to Korea, attributed his survival exclusively to her divine interception. 17 The goddess had become eligible for an official recommendation to the throne and a public reward, exactly because she had, in the first place, saved the state-official Lu Yundi and only to a lesser extent the gentleman Lu. 18

The first section of the TF lists thirteen honours in Song times, among them the conferment of an honorary plaque, the bestowment of the ranks "furen" ("Lady") and "fei" ("Princess"), plus honorary titles for the family members of Lin Moniang (1200).

In 1259, Tianfei is promoted to "Princess of Manifested Assistance". After this there is a report lacuna in the text until the Yuan dynasty: 19

3.3. YUAN

In the Yuan dynasty (1206-1368) things remain relatively quiet around the goddess who, during this period is - due to her origin - still strongly attached to the maritime context of Southern China. It may well be so that a more 'upcountry' orientation of the Mongol Court contributed to this situation. All honours mentioned in the TF for this dynasty took place exclusively in connection with grain/rice by means of coastal or inland navigation shipping's from the south to the capital which had been transferred to the North.

Altogether twenty entries during the Yuan dynasty inform us that the public transports had reached their destinations "[...] completely and undamaged [...]" and that the goddess had thereby helped secure the sustenance of the population - an immediate concern of the state. In this context special offering ceremonies were conducted (between the 25th of August 1329 and the 20th of January 1330) along the south Coast of China in fifteen temples that are identified by their names; the texts of these offerings usually evoke the importance of the sea transports to the state as well as the dangers of "[...] winds and waves [...]", which were weathered with the help of the goddess.

DATE |

TF PAGE |

TITLE |

1122

1155

1156

1157

1183

1190

1198

1208

1253

1255

1256

1259

|

1,27f.

1,28

1,28

1,29

1,29

1,29

1,30

1,31f.

1,32f.

1,33

1,33

1,33

|

Shunji• (Compliant Assistance)

Chongfu Furen• (Lady of Superior

Happiness)

Linghui Furen• (Lady of Divine Grace)

Linghui zhaoying Furen• (Lady of Di-

vine Grace and Clear Responsiveness)

Lingci zhaoying choingshan fuli

Furen• (Lady of Divine Mercy, Clear

Responsiveness, Superior Grace, and

Lucky Prosperity)

Linghui Fei• (Princess of Divine Grace)

Zhushun• (Helpful Complaisance)

Huguo zhushun jiaying yinglie Fei•

(Heavenly Princess Who Watches

Over the Country, Who is of Helpful

Complaisance, Excellent Respon-

siveness, and Superior Chastity)

Linghui zhushun jiaying yinglie

xiezheng Fei• (Princess of Divine

Mercy, Helpful Complaisance, Excel-

lent Responsiveness, Superior Chasti-

ty, and Supportive Uprightness)

Linghui zhushun jiaying ciji Fei•

(Princess of Divine Mercy, Helpful

Complaisance, Excellent Responsi-

veness, and Compassionate Aid)

Linghui xiezheng jiaying shanqing Fei•

(Princess of Divine Mercy, Support-

ive Uprightness, Excellent Responsi-

veness, and Good Blessings)

Xianji Fei• (Princess of Manifested

Assistance) |

The first section of the TF (p.2) lists five bestowments of honorific titles: the report continues with the year 1281, i. e., twenty-two years after the last TF entry of 1259, with the appointment of the goddess to "Heavenly Princess Who Watches Over the Country", and "Who is of Bright Manifestation" (TF, pp. 2-3). Here, for the first time, the goddess is awarded the rank of "Tianfei" ("Heavenly Princess"). This re-investiture (the title-part of "huguo", • "Who Watches over the Country", had already been granted in 1208) contains the following exculpatory passage: "Since the unification of the empire We did not find time and leisure to bestow upon you nobility titles. The civil authorities have now brought this fact to Our notice [...]." (TF, p.3).

For the first time since the year 1329 we find here the combination of three title parts which had been granted on separate occasions before and which point to the increasing significance to the state of the goddess: "huguo" ("Watches Over the Country", 1208), "fusheng" ("Supports the Emperor"; 1299), and "bimin" ("Cares for the People"; 1299).

3.4. MING

During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) the activities of Tianfei are characterized by a few, albeit new, themes, while earlier ones are no longer recorded in the TF. The activities of the goddess respond to the outward-bound orientation and policy during this period of the Ming dynasty. They have extended from a national to an international context. The construction of a temple near the capital (i. e., far away from Fujian's• coasts) dedicated to Tianfei reflects this newly enhanced significance.

The belief in Tianfei as a protecteress and maritime patron deity gives, for instance, evidence of the psychological need of sailors, fishermen, and merchants to compensate and overcome the then still existing technological and nautical under-development with divine assistance on a supernatural level, specially when facing the imminent dangers at sea. 21 But also during Ming times when the Chinese navigation and nautical technology had reached a climax and large 'treasure ship' fleets under the command of the Court eunuch Zheng He conducted naval expeditions to Southeast Asia - Borneo, Bengal, and "[...] foreign countries of all kinds [...]" (TF, p.9), and even all the way to the east coast of Africa - Tianfei also went abroad as an additional protection for the ships, when her statues were worshipped in small shrines. 22

DATE

|

TF PAGE

|

TITLE

|

1281

1289

1299

1314

132920

|

2,3

2,3

2,4

2,4

2,4-5,34

|

Huguo mingzhu Tianfei• (Heavenly

PrincessWhoWatchesOverthe

Country,andWhoisofBrightMa-

nifestation)

Xianyou• (ManifestedHelp)

Fusheng bimin• (SupportstheEm-

peror,andCaresforthePeople)

Guangji• (ExtensiveAid)

Huguo fusheng bimin xianyou guangji

linggan zhushun fuhui huilie mingzhu

Tianfei• (HeavenlyPrincessWho

WatchesOvertheCountry,Supports

theEmperor,CaresforthePeople,

WhoisofManifestedHelp,Support-

iveComplaisance,BlessedMercy,

HonourableChastity,andBright

Manifestation)

|

The internationalization of Tianfei's realm of activities had become possible only through this mobilization: because of the shrines that were installed on board ship and, thus, were 'portable', Tianfei's sphere of influence expanded much faster than it would have been the case in a more conventional development and spread of the cult. The usually existing barriers of local, regional, territorial limitations, etc. fell away abruptly. 23

The TF lists ten maritime expeditions for the time between 1409 and 1432. 24 Zheng He is mentioned two times in person, and it is always Tianfei who distinguishes herself through her protection and aid during storms at sea, dangerous encounters with "barbarians" of Southeast Asia, etc.

Accordingly, the first section of the TF (p.2) registers two bestowments of honours (1372; 1409, simultaneously with this second date the construction of a temple for her near the capital and the installation of a temple plaque) are mentioned, as well as seven special sacrificial offerings - all in connection with the expeditions overseas and the ambassadorial journeys - and a temple renovation (1430-1431). The second section (TF, pp. 7-9) lists for the same report period two of the texts of the title proclamations. The section that contains the legend Tianfei has eleven Ming time episodes.

The TF dates the first Ming time entry into 1372 (Taizu• reign, year 5) who in his Decree, similar to Yuan Shizu• (Kublai Kahn) in 1281, apologizingly remarks: "Since We have ascended to the throne, We did not find the opportunity to grant you glorification." (TF, p.8).

The title-contents are more general again and resemble earlier ones. What is new is the promotion to "Shengfei" ("Holy Princess") under Ming Taizu [Hongwu] (r.1368-†1398) in 1372. Ming Chengzu [Yongle] (r.1403-†1425) changed this back to "Heavenly Princess" in 1409. Since 1407 regular offerings were conducted in the capital on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month (at the lantern festival), and on the twenty-third day of the third lunar month (the 'birthday' of the goddess.)25

For the first time we find the topos of the phenomenon of divine "Luminous Piety"26 - her favourite form of manifestation on sea - as well as divine manipulations of the weather, dream manifestations as a means of communicating with humans, etc.

Following the year 1431, there is again a lacuna in the report of the TF, which ends only with the beginning of the Qing• dynasty.

3.5. QING

Between the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) we have in the TF a lacuna that spans nearly two hundred and fifty years. In the section of the Qing dynasty we find several very detailed episodes whose 'plots' are interwoven, taking place between 1680 (Kangxi reign, year 9) and 1727 (Yongzheng• reign, year 4). A greater attention to historical credibility can be observed here. Besides, it seems likely that the closer temporal distance between the reported events and their recording and compilation in the TF have contributed to this prolixity, all the more since one of the protagonists, Lin Linchang,• is the author of he third preface of our text.

DATE |

TF PAGE |

TITLE |

1372

1409

1415-

-1431

|

2,7/8

2,8,37

2,8-9,39

|

Zhaoxiao chunzheng fuji ganying

Shengfei• (Holy Princess Who is of

Luminous Piety, Pure Uprightness,

Trustworthy Aid, and Affecting

Responsiveness)

Huguo bimin miaoling zhaoying hon-

gren puji Tianfei• (Heavenly Princess

Who Watches Over the Country, Cares

for the People, Who is of Mysterious

Efficacy, Clear Responsiveness, Great

Benevolence, and All-Encompassing

Aid)

Further sacrificial offerings/monetary

rewards to her family/temple renova-

tion |

Again, the goddess' main area of activities has changed. The times of the spectacular maritime expeditions of Zheng He are over, and it is only once that her help is now mentioned in connection with an ambassadorial journey by sea - this time to the Liuqiu islands (the Ryukyu archipelago). Instead, we now find high ranking military and civil officials, pestered by bandits and pirates, rebels and Ming-loyalists such as the notorious Zheng Chenggong• (Koxinga).

Mustering all her proven resources and abilities, Tianfei during this time shows herself to be on the height of her divine power and efficacy. The big successes won by the goddess in this belligerent context and her great merits are reflected in the amount and quality of her public rewards. Besides gifts of Imperial incense and silk, ceremonials offerings to her, temple renovations as well as the construction of new temples, monetary rewards, horizontal plaques and steles with commemorative inscriptions the bestowments of titles are just one kind of many diverse forms of public gratification and honours. 27

In the TF we can differentiate the narration into the following three main episodes, whose plots are, as mentioned above, partly intertwined:

1. 1680 (Kangxi reign, year 19): Admiral Wan Zhengse• fight successfully against bandits/pirates near Xiamen• and Jinmen• and receives Tianfei's divine support (TF, pp. 9-10)

2. 1683 (Kangxi reign, year 22): Ambassadors Wang Ji and Lin Linchang• are sent to the Liuqiu islands. Following a record-time passage to the islands, they get into a tempest on their way back, which they only survive with the help of the goddess (TF, pp. 10-11).

3. 1682-1684 (Kangxi reign, years 21-23): Admiral Shi Lang• undertakes the pacification of the Penghu• islands (the Pescadores) and of Taiwan. While on campaign, the goddess supplies his troops with fresh spring-water by means of miracles (TF, pp. 11-13). In 1684, a Director of the Ministry of the Rites, Ya Hu,• conducts in the Meizhou• temple of Tianfei the special sacrificial; offering of thanks (TF, pp. 12-13).

4. This episode takes place between 1721 (Kangxi reign, year 60) and 1727 (Yongzheng reign, year 4): Beginning of the pacification campaign, with Admiral Lan Tingzhen• as the protagonist.

18th February 1726: Admiral Lan requests to the throne the bestowment of honours upon Tianfei. The goddesses had rendered support, for instance, in connection with a speedy passage to Taiwan and the procreation of drinking water in barren places for the marines; in order to facilitate the navigation of the battle fleet she raises the water level; by employing heavenly ghosttroops she assists during battles (TF, pp. 13-16). As a reward for this, a horizontal plaque with four characters written on it by Imperial calligraphy is installed in each of the three temples at Meizhou, Xiamen, and Taiwan. These events are described in some detail in the TF. Lan's letter of acknowledgment dated the 11th of January 1727 (Yongzheng reign, year 4, month 12, day 20) and at the same times marks the latest date mentioned in the TF (cf. above).

At this period of time Tianfei's realm of activities and supernatural power had - starting from the South Chinese coastal provinces ofd Fujian• and Guangdong - continued to spread over Taiwan, the Liuqiu and Penghu islands, the island of Meizhou (her place of birth), down to Southeast Asia and East Africa (with Zheng He's expeditions). The former local deity had become a powerful international goddess.

DATE |

TF PAGE |

TITLE |

1680

(1683-)

1684

(1682-)

1684

(1721-)

1727

|

2,7/10,41

2,10/11,41ff.

22,11

/13,41ff

13-14,16

|

Huguo bimin miaoling zhaoying

hongren puji Tianfei• (Heavenly

Princess Who Watches Over the

Country, Cares for the People, Who

is of Mysterious Efficacy, Clear

Responsiveness, Great Benevo-

lence, and All-Encompassing Aid)

Spring and Autumn sacrifices

Sacrificial ceremonies

Horizontal plaque: Shenzhao haibi

ao• (Divine Brightness Above the

Oceans) |

The first section of the TF (p.2) records the granting of titles (1680), Spring and Autumn sacrifices (1684), and special sacrificial offerings as well as the bestowment of a temple plaque (1727). The very detailed report of this last occurrence is given in the second section of the TF (pp. 9-16). The last eight episodes in the legend-part of the TF also deal with Qing time events.

§4. RECAPITULATION

The main name of Tianfei's divine working as presented in the TF is, as we have seen, her supernatural assistance of the state, her protection for officials and ambassadors while exercising their official tasks. Ultimately, this means of support of the emperor and the state-orthodoxy represented by him.

The goddess 'specialized' functionally in accordance with the different dynasties and adapted her activities to their respective 'needs', i. e., the goddess was 'adjusted" by the state by a changing employment which, in fact, meant a continuous reinterpretation of the goddess. During Qing times the titles granted her increasingly (at least, a little bit) reflect these changes with regard to the relationship between title contents and the underlying historical cause for their bestowments.

Would it, then, be tenable to deduce from this evidence the above-mentioned "[...] confinement by means of extension [...]"? And, how concrete is the connection between the contents of title-parts and their historical background? Excerpt for those parts that stress the general numinous efficacy ling, the orthodox loyalty to the state, and other pro-Confucian virtues of the goddess, surely titles with more concrete contents were granted her as well. The more the 'titles' (Titulatur) of Tianfei grew in quantity and the closer the connection between the reason for the granting and the contents of the title became, the stronger the titles confined to the goddess and bound her to their contents. But I would consider it, on the limited grounds of evidence that I have adduced here, too bold to speak of a real "individualization".28

Nevertheless, the development of omnipotent characteristics, comparable to those of conceptions of God in monotheistic universal religions, was effectively inhibited. In this respect the 'young' goddess during Song times had more indefinite power - quasi still 'undefined' ling - than the later one. Her ling had not yet manifested itself into diverse aspects but formed a still untapped source of divine efficacy as a whole.

The title-parts are similar to individual elements of a big and complex unit construction system (or, a box of bricks, if you prefer) which included the above mentioned numerous further possibilities of public honours and state-cultic measures. This provided the officials, whose duty it was to conduct offerings, etc. on behalf of the Emperor, with a versatile tool which they could apply to all kinds of situations with considerable subtlety. This does not touch upon the question whether a definite title-part was only granted once or to only one particular deity, but whether we would be able to identify the title-parts because of their contents with one and only one particular deity. Again, we cannot confirm this. Ultimately, the title-contents are rarely unambiguous enough to warrant their identification with only one particular historical event that might have been the reason for their bestowment or with one particular deity.

On a meta-level we can relate some of the titles to more general topoi, such as 'transport', 'battle', escort', 'protection for shipping', 'pacifying the boundaries'. But even this evident observation does not apply to a part of the later-granted titles.

The above-mentioned 'absorption by means of integration' seems to be easier to be confirmed, since its describes a formal, quantitative phenomenon: every bestowment, i. e., every further addition of a title-part, had exactly the effect of formally integrating the deity further into the state cult system and the orthodox context. In this context the reason for the bestowment or the contents of the title-party were of no importance.

If single title-parts are not sufficient for an easy identification, would it be permissible, then, to identify and individualize a particular deity maybe by means of the total sum and concrete combination of all of the title-parts?! In short, would be Titulatur as a whole serve this purpose? In order to answer this interesting question we would, however, first of all have to carry out further research and compare, e. g., different 'titles' (Titulaturen) of other important deities of the state cult pantheon. Such an investigation, however, must presently await another occasion. **

NOTES

** Revised version of the paper: WÄDOW, Gerd, Lun Tianfei chenghao zai guojia chongbai zhong de yiyi «论天妃称号在国家崇拜中的意义», in INTERNATIONAL MAZU CONFERENCE (澳门妈祖信俗历史文化国际学术研讨会), Macao, 21-25 April 1995 - [oral communication...]. See: T'ien-fei hsien-sheng lu. "Die Aufzeichnungen von der manidestierten Heiligkeit der Himmelsprinzessin." Eileitung, Übersetzung, Kommentar (T'ien-fei hsien-sheng lu. "The Records of the Manifested Holiness of the Heavenly Princess." Introduction, Translation, Commentary), in "Monumenta Serica Monographs, (29) 1992, Institut Monumenta Serica/ Sankt Augustin - Steyler Verlag/Nettetal - For a more detailed discussion of this paper which contains the complete Chinese text of the TF, as well.

1 Punishment and coercion were, as a rule, employed more reluctantly.

2 In the documents under consideration here, the popular name 'Mazu' does not occur.

3 Tianfei xiansheng lu «天妃显圣录» (The Records of the Manifested Holyness of the Heavenly Princess), in "Taiwan wenxian congkan" «台湾文献丛刊» ("Documental Corpus of Taiwan"), Taiwan yinhang jingji yanjiu 台湾行经济研究室 Bureau of Economic Research of Taiwan, (77) 1960 - In this edition, the textual story of the TF is related in some detail in an afterword by one of the editors, Bai Ji (pp.79-85). According to him, the textus receptus of the TF was compiled in three phases and in its present form postdates 1727 (See: TF, loc. cit.).

4 The individual petitioner and private worshipper, however, should only indirectly rely on securing for himself the benevolence and help of a deity, in more or less the same way he used when approaching an this-worldly official: He asked a favour of the deity and formulated his request; he presented the deity with appropriate gift (not heavy- handed bribes) and promised further attention and offerings, provided his problems and affairs were dealt with by the deity in a satisfactory manner.

5 Thus, e. g.: "If We [i. e., the Emperor] did not bestow upon you [i. e., the deity] the grace of commendations, how would your holy traces become known?!" (TF, p.4); or: "If there were no praiseful commendations, how could one give notice of your extraordinary superiority?!" (TF, p.9); "And, if We, for this special reason, would not confer a title of reputation, there would be no way to praise the admirability of her secret help or to promulgate her awe-inspiring efficacy." (TF, p. 12). The purport here seems to imply that it depends on the goddess herself to secure her fame, the offerings presented to her, her wellbeing and, last but not least, her existence in the consciousness of her believers.

6 Which is why he can bestow honours on them.

7 In the religious history of China, these unofficial or heterodox cults have more than once been the point of departure for 'messianic' or subversive movements. Even today, in the People's Republic of China, for example, folk religious practices and customs are defined as mixin huodong (superstitious activities) and thus are excluded from the protection of religious freedom under Article 36 of the Chinese Constitution of 1982. This exclusio per definitionem provides an eloquent example of the unchangeable traditional distrust of the state against 'heterodox' forms of religion.

See: WÄDOW, Gerd, Neues zum Thema 'Religion heute' aus der Volksrepublik China, in "China Heute. Informationen über Christentum und Religion in chinesischen Raum", 9 (76) 1994, pp.186-188 (especially p.187); WÄDOW, Gerd, Shi Youxin: Bei abergläubischen Aktivitäten darf man die Dinge nicht gleichgültig laufen lassen, in "China Heute. Informationen über Christentum und Religion in chinesischen Raum", 2 (30) 1987, pp.24-28.

8 YANG, C. K., Religion in Chinese Society, Berkeley -Los Angeles - Oxford, University of California Press, 1970, [repr. Taipei, Southern Materials Centre, 1978], pp. 145-146, passim - The author pays closer attention to the distinction between "orthodox" and "heterodox". He stresses that the differentiation between guansi• (official) and minsi• (folk religions) offerings relates less to their content than to their 'sponsorship' (p. 145). See: LIU, Kwang-Ching, ed., Orthodoxy in Late Imperial China, Berkeley - Los Angeles - Oxford, University of California Press, 1990 - On orthodoxy.

9 This reveals an essential difference polytheism and its multitude of deities, gods, and goddesses on the one hand and monotheism with a single, almighty God (whose name may even be taboo) on the other hand. Such a translation of the single and highest god and a layer of mediators in between his sphere and that of ordinary people can, of course, be found in different variations in different religions.

10 This means that the deity embodies everything and is able to do anything which is confirmed or attributed to it in its titles; everything else which is not expressly stated, however, in reverse, the deity does not embody, cannot do (or not yet).

11 WATSON, James L., Standardizing the Gods: The Promotion of T'ien Hou ('Empress of Heaven') Along the South China Coast: 960-1960, in JOHNSON, David -NATHAN, Andrew J. - RAWSKI, Evelyn S., eds., "Popular Culture in Late Imperial China", Berkeley - Los Angeles -Oxford, University of California Press, pp.292-324 - The author has investigated this question in the context of the Tianfei cult.

12 Tianfei had already been promoted to Tianhou (Heavenly Empress) at that time. The last-mentioned title-part, jiayou, was presumably granted her in 1872 (Tongzhi reign, year 11) by the state cult system, and at the same time was the title she was to receive. See: KUN Gang, comp., Da Qing huidian shili «大清会典事例» (A Collection of Exemplary Facts Occured During the Qing Dynasty), 北京 Beijing, Huidian guan 会典馆 Documental Repository, 1899, juan• 445, p.21; juan 446, p.9.

Also see: ZHAO Ergang, Qing shi gao «清史稿» Draft of the History of the Qing Dynasty, 北京 Beijing, Zhonghua 中华 China Publishers, 1977, ce 10, juan 84, p.2549 ff. - For a different date: 1901 (Guangxu• reign, year 27).

13 Her folk names, as well as the folk religious dimensions of the Mazu-cult, cannot be dealt with here, however, since this would go far beyond the scope of this paper.

14 WATSON, James L., op. cit., p.293 - The author points out that this procedure was an often-employed method for officials to prove their loyalty to the state. This seems to be the reason why, through state sponsorship of such officially approved cults in south China during the middle of the Qing dynasty, a relatively small number of such 'approved' deities had superseded local deities.

15 Merchants too, are mentioned explicitly only once in the first nineteen episodes. This surely does not reflect their historical importance; members of the merchant class are very likely to have implored to the goddess many more times than their rather negligent treatment in the TF suggests. Again, this shows the above-mentioned officious intention and the selectiveness of the compilers of the TF.

16 In connection with the different stages of development - from local beginnings, regional and national spreading, to an international significance - this marks a rather early stage. Notwithstanding the continuity and length of a cult's existence, of course, not all local cults survived and thrived to experience such a territorial expansion.

17 TF, pp. 1, 27 ff. - episode 24: Zhuyi zhuling «珠衣著灵».

18 Such reports to the throne and the responding issuing decrees rewarding the deities served the promulgation of an 'orthodoxized' cult as well as the support of an orthodox Confucian world view, the well-ordered and stable condition of the empire, and the stabilizing and consolidation of the imperial power and sphere of influence. COUVREUR, S., S. J., ed., trans., Li Ki [Liji «礼记»] ou Mémoires sur les Biensséances et les Cérémonies. Texte chinois avec une double traduction en français et latin par S. Couvreur S. J., 2 vols., Hou Kien Fou, Imprimerie de la Mission Catholique, 1913 [2nd edition - Chinese text with a double translation in French and Latin] vol. 2, p.268, juan 20: "Ji fa" ("珩法") - Already here are mentioned the criteria and necessary qualifications: "D'après les règlements des sages souverains de l'antiquité, on faisait des offrandes aux grands hommes qui avaient donné des lois au peuple, à ceux qui avaient porté leur dévouement jusqu'au sacrifice de leur vie, à ceux qui par leurs travaux avaient affermi l'État, à ceux qui avaient pu détourner un châtiment du ciel, à ceux qui avaient pu éloigner un grand malheur causé par les hommes." At this particular occasion Tianfei was honoured with the granting to her of a temple plaque, a temple tax abatement, and a sacrificial offering in the temple at Putian.

19 WIETHOFF, B., Der staatliche Ma-tsu Kult, in "Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft", 116 (2) 1966, pp.311-357 - For a detailed presentation of the Tianfei titles.

20 In connection with the 1329 title bestowment the following dates and temples as places of sacrifice had been advised (see: TF, pp.4-7): 25th of August 1329: Zhigu miao (temple); 9th of September 1329: Huaian miao; 22nd of September 1329: Pingjiang miao; 24th of September 1329: Kunshan miao; 26th of September 1329: Lucao miao; 3rd of October 1329: Hangzhou miao; 6th of October 1329: Yue miao; 11th of October 1329: Qingyuan miao: 28th of October 1329: Taizhou miao; 2nd of November 1329: Yongjia miao; 9th of November 1329: Yanping miao; 7th of December 1329: Lingci zhi miao / Min gong; 14th of January 1330: Baihu miao; 15th of January 1330: Meizhou miao; 20th of January 1330: Quanzhou miao.

21 A similar case is the ahistorical deity Christopher, who was in the West counted among the Fourteen Helpers in Need (Nothelfer) since the Middle Ages.

22 MILLS, J. V. G., ed., trans., Ma Huan Ying-yai Sheng-lan 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores' [1433]. Translated From the Chinese Text Edited by Feng Ch'eng-Chün With Introduction, Notes and Appendices by J. V. G. Mills, (Hakluyt Society Extra Series 42), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1970 - For the report of Ma Huan, Zheng He's companion of his voyages.

23 HANSEN, Valerie Lynn, Changing Gods in Medieval China, 1227-1276, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990, passim. To this bear analogy her gaining ground upon the interior of China aboard the merchant-ships, and, as the folk religious patron deity of the fisherman, she has successfully kept her place on board their fishing-boats up to this day.

24 DUYVENDAK, J. J. L., The True dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century, in "T'oung Pao", (34) 1939, pp.341-412.

25 WIETHOFF, B., op. cit., pp.327-338.

26 Together with an especially fragrant smell, this widespread phenomenon belongs to the standard topoi which accompany divine manifestations, as for example, in Buddhism. In navigation at sea it is a widely known electrostactical phenomenon called St. Elmo's Fire, which we find described already by Pliny the Elder (AD °23/24-†79) in his Historia Naturalis.

27 Due, of course, to its officious perspective and intention of the compilers, it is mentioned nowhere in the TF that in such confrontations Tianfei was also implored by the pirates for assistance in battle [...]. See: WATSON, James L., op. cit., pp.292-324 - For this ambivalence of deities, who could mean different things to different groups and individuals at the same time and even the same occasion This antagonism sheds also light in the in praxis sometimes rather blurred distinction between the heterodox and the orthodox - in this instance, with regard to the relative position of different groups of Tianfei's worshippers and their relationships to the goddess.

28 WÄDOW, Gerd, T'ien-fei hsien-sheng lu. "Die Aufzeichnungen von der manidestierten Heiligkeit der Himmelsprinzessin." Eileitung, Übersetzung, Kommentar, in "Monumenta Serica Monographs, Institut Monumenta Serica/Sankt Augustin - Steyler Verlag/Nettetal, (29) 1992, passim - For a different perspective.

* Ph. D. in Sinology, Science of Comparative Religion and History of East Asian Arts, by Bonn University. Full-time member and scientific collaborator of the editorial office at the Monumenta Serica Institute, Sankt Augustin, Germany. Librarian of the Sinological Seminar, Bonn University. Researcher on the history of Chinese religions; Chinese folk religion and the relationship between folk cults and the orthodox Chinese state cult, Chinese moral, ethics, and philosophy; and the history of Chinese art and architecture. Author of numerous articles and publications on related topics. including T'ien-fei hsien-sheng lu: "Die Aufzeichnungen von der manidestierten Heiligkeit der Himmelsprinzessin": Eileitung, Übersetzung, Kommentar (T'ien-fei hsien-sheng lu: "The Records of the Manifested Holiness of the Heavenly Princess ": Introduction, Translation, Commentary).

start p. 35

end p.