[INTRODUCTION]

Earlier this year, I undertook two projects at the Museu da Macau (Aomen bowuguan• / The Macao Museum) of Macao. The first entails research into the religious life of the people of Macao. In the course of frequent fieldwork research visits to temples in Macao, in particular the three principle temples: the Mazu ge (miao) • (Ama Temple), Lianfeng miao• (Lotus Temple) and the Puji chanyuan• (Temple of All Encompassing Aid), I have made a string of new discoveries. The conclusions I have arrived at enable me to correct a number of mistakenly held beliefs which are prevalent both popularly and in academic circles. The present paper comprises a special report on some important discoveries concerning the Ama Temple and a commentary of the accompanying illustrations.

PREVIOUS PAGE: View from the hill path leading to the Ama Temple hill down towards the Inner Harbour. ZHAO SHAO 杨绍. 1996. Oil on canvas. 50 cm x 40 cm.

PREVIOUS PAGE: View from the hill path leading to the Ama Temple hill down towards the Inner Harbour. ZHAO SHAO 杨绍. 1996. Oil on canvas. 50 cm x 40 cm.

§1.

Three lines of text are carved on the stone of the rear wall of the shrine in the Shenshan diyi• (First Hall of the Holy Mountain). The uppermost line reads: "Qinchai zongdu Guangdong Zhuchi shiboshui jian jianfyanfa taijian Li Feng jian•" ("The Imperial Envoy, Governor General of Zhuchi in Guangdong, collector of municipal shipping tax and enforcer of the salt laws / Built by the Eunuch Li Feng") (illustration 1) The second line reads: "haiyue zhongying•" and the third: "ruzai•". (illustration. 2) Because these inscriptions have been constantly concealed in semi-darkness by the statue of the Tianfei (Heavenly Princess) and the holy shrine, they have remained unnoticed for several hundred years, so it has been impossible for scholars to study them and publish their findings. On one occasion when I was visiting the site, I watched the caretaker at the temple cleaning the shrine, and took the opportunity to ask for permission to take a closer look. This was the first time I saw that there really was an inscription there. At first, I could only see the two ends of the first line of characters, which seemed to be split into two parts: "The Imperial Envoy, Governor General of Zhuchi in Guangdong [...]" and then "Built by the Eunuch Li Feng." Although there were more than ten characters which I had not yet seen, I could already guess that the two were part of a single sentence describing Li Feng's official title. I immediately recognised that this stone inscription concealed an important historical secret and was of some academic interest. It was necessary to work out the whole inscription as soon as possible and study it in detail so that the information could be published. Now, thanks to a great deal of support from people in various places, and after many visits to the site to look and take photographs, I am finally able to present a photographic survey. On the basis of this newly-discovered stone inscription, in particular the line about Li Feng, I can ascertain that the inscription was made at the behest of the builder of the temple to record the date of the temple's construction. This evidence is corroborated the inscription "Built by the merchants of Dezi jie• [Dezi Street] in the year yisi• [1605] of the reign of the Wanli Emperor the Ming dynasty" on the stone lintel of the doorway into the Shenshan diyi• (First Hall of the Holy Mountain). Further evidence is found in Aomen Jilue (Monograph of Macao), written during the reign of the Qing dynasty Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-† 1796) by Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin, tongzhi• (Superintendents) of Macao. There is a reference to the ghost of the Heavenly Princess at the time of the Wanli Emperor which appeared at Ma Jiao shan• (Ma Kok Hill). This is the popular legend of why the Temple of the Heavenly Princess was built in that place. 1 Further collateral evidence is provided by references to this temple in the oldest surviving early Qing stone inscriptions of poetry and other texts found on the hill where the temple is located.

1.1.

It is certain that this shrine and the hall were built at the same time in the 1605 (Wanli reign, year 33, yisi•) because no temple could have existed with just the hall or just the shrine alone. Therefore, both must have been built at the same time and been parts of the original temple, which would have been small and simple. If at that time either the Ama Temple (Temple to the Heavenly Princess) had existed for a number of decades or even for a century or more, then the earlier building would simply have been extended or rebuilt on the old foundations. Also, one might have expected the inscription in the shrine hall to read 'Rebuilt by Li Feng', rather than "Built by Li Feng". Similarly, the record of the original date of the original construction and subsequent renovation in the inscriptions carved on the lintel of the door into the First Hall of the Holy Mountain would not read: "Built by the merchants of Dezi jie in year yisi of the reign of the Wanli Emperor in the Ming Dynasty" but would indicate a different year and different benefactors. **(illustration. 3)

In addition, if it was common knowledge in in Macao that there was a temple which had been built earlier than the Qianlong period of the Qing dynasty or even the Wanli period (r. 1573-† 1620) of the Ming dynasty, then Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin, as compilers of the Monograph of Macao, would certainly have known about it. They would not have recorded the following in their writings: "Legend has it that in the time of the Ming Emperor Wanli [...]," but would instead have included the date of the earlier legend. We might well ask on what grounds Macanese people today claim to understand the history of the construction and renovation of the temple better than the people who left records in the form of inscriptions on stone door lintels. Furthermore, how can people prove that their legends about why the temple came to be built are in any way more informative, authentic or credible than Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin's records? Unless we have cause to question or contradict the records of the building and renovation of the temple inscribed on the stone lintel, which constituted information freely available to people in the past, we cannot question the authority of Yin Guangren and Zhang Rulin's records about the original story of how the temple was constructed. Indeed, there are no documents or writings which might prompt us to do so. Yet when in 1984 it was suggested that the Ama Temple was built during the reign of the Ming Emperor Chenghua• (r. 1465-†1488), the suggestion was accepted as indisputable fact, without scholars having published on the subject or having been to the temple to look for themselves. (illustration. 4) For this reason a number of mistaken impressions have come to be widely believed. In fact, the Aomen shi gouchen• (Treatise on the History of Macao) by the well known Macanese historian Huang Wenkuan• is the only work which cites the evidence of the stone inscription on the door lintel with the date "yisi of the reign of the Wanli Emperor [...]" [i. e., Wanli reign, year 33], and goes on to put the date of the construction of the temple at 1605. 2 This is a brilliant deduction which was arrived at only after intelligent thought, and it is regrettable that it has been consistently rejected out of hand by gullible Macanese who have been misled by information on a recently erected monument, so that Huang Wenkuan's deduction has not until now been subjected to proper scholarly scrutiny. 3 The folly of current thinking cannot be contradicted convincingly, and the real truth in this issue is difficult to prove. Now, this newly discovered inscription saying that Li Feng built the temple and the shrine can be compared with the already known stone inscription describing the history of the temple's building and renovation to form doubly convincing evidence. Add to this the poetry carved inside the temple during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor and the record in the Monograph of Macao that the generally accepted date of the construction of the original Tianfei miao (Temple of the Heavenly Princess) was during the Wanli period and the facts are watertight: the authority of these pieces of evidence are incontrovertible. Therefore on the basis of this cast-iron proof and by rigorous logic, we can conclude that the temple was built originally in 1605. One recent story of the modem era, popularly believed for the last ten years or so, maintains that the Ama Temple was built during the reign of the Ming dynasty Chenghua Emperor, and so is more than five hundred years old. This theory is not corroborated by evidence in the way that the 1605 theory is, and is not in fact supported by any convincing proof. So by bringing evidence to support the 1605 theory, we are at the same time able to disprove completely the groundless claims that the temple has a history of five hundred years. As was pointed out by the famous Macanese historian Dai Yixuan: • "A fact is only as valuable as the evidence which proves it; nothing should be believed without proof."4 This is a basic principle of our profession which we must adhere to when we undertake historical research.

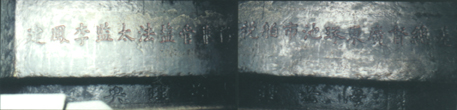

Illustration. 1

The newly discovered inscription carved on the back of the shrine in the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain). The inscription reads:

"Constructed by the Imperial Envoy. Governor General of Zhuchi in Guangdong, the Eunuch Li Feng, collector of municipal shipping tax and enforcer of the salt laws."

This discovery is of considerable archaeological value, and provides direct evidence with direct significance for research into the date of the temple's original construction and subsequent renovation, its relationship the contemporary bureaucracy, the scope of the Ming administration's influence in the Macao peninsula in 1605 (Wanli reign, year 33), the original appearance and configuration of the temple, its original name and other important issues.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yao lin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 1

The newly discovered inscription carved on the back of the shrine in the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain). The inscription reads:

"Constructed by the Imperial Envoy. Governor General of Zhuchi in Guangdong, the Eunuch Li Feng, collector of municipal shipping tax and enforcer of the salt laws."

This discovery is of considerable archaeological value, and provides direct evidence with direct significance for research into the date of the temple's original construction and subsequent renovation, its relationship the contemporary bureaucracy, the scope of the Ming administration's influence in the Macao peninsula in 1605 (Wanli reign, year 33), the original appearance and configuration of the temple, its original name and other important issues.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yao lin 邝耀林.

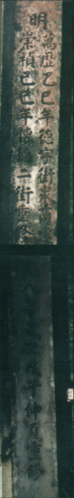

Illustration. 2

More of the newly discovered inscription: "ruzai" and "haiyue zhongying".

These two inscriptions indicate clearly that the Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess) was originally conceived within the context of orthodox Confucian officialdom.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 2

More of the newly discovered inscription: "ruzai" and "haiyue zhongying".

These two inscriptions indicate clearly that the Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess) was originally conceived within the context of orthodox Confucian officialdom.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 3

Inscription carved on the front face of the lintel of the original Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The inscription reads:

"Built the merchants of Dezi jie [Dezi Street] in year yisi [1605] of the reign of the Wanli Emperor in the Ming dynasty. Rebuilt by the merchants of Huaide Second Street in year yisi• [1629] of the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor."

This is a reliable record of the history of the temple's construction and subsequent restoration. A comparison of the first line of this inscription with the newly discovered inscription on the shrine,"[...] built by the Eunuch Li Feng [...]", proves that this temple was owned by the official government and supported by the commercial community, and that both the temple and the shrine were built in the same year.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 3

Inscription carved on the front face of the lintel of the original Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The inscription reads:

"Built the merchants of Dezi jie [Dezi Street] in year yisi [1605] of the reign of the Wanli Emperor in the Ming dynasty. Rebuilt by the merchants of Huaide Second Street in year yisi• [1629] of the reign of the Chongzhen Emperor."

This is a reliable record of the history of the temple's construction and subsequent restoration. A comparison of the first line of this inscription with the newly discovered inscription on the shrine,"[...] built by the Eunuch Li Feng [...]", proves that this temple was owned by the official government and supported by the commercial community, and that both the temple and the shrine were built in the same year.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 4

The Mazuge wubai jinian beiji (Monument to Commemorate the Quincentenary of the Ama Temple).

Erected in 1984, it incorrectly records the date of the temple's construction as 1484.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 4

The Mazuge wubai jinian beiji (Monument to Commemorate the Quincentenary of the Ama Temple).

Erected in 1984, it incorrectly records the date of the temple's construction as 1484.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

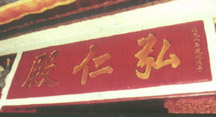

Illustration. 5

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The inscription reads:

"Worship the Imperial Dynasty".

It proves that the construction of the temple was an official government project.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao谭世宝.

Illustration. 5

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The inscription reads:

"Worship the Imperial Dynasty".

It proves that the construction of the temple was an official government project.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao谭世宝.

Illustration. 6

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the front entrance to the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

It is the evidence that this is the oldest structure in the temple complex.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao谭世宝.

Illustration. 6

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the front entrance to the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

It is the evidence that this is the oldest structure in the temple complex.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao谭世宝.

Illustration. 7

Poetry about the temple carved in stone in the early Qing dynasty.

It explains that the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain)is both the oldest and the most important of the buidings in the temple complex.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 7

Poetry about the temple carved in stone in the early Qing dynasty.

It explains that the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain)is both the oldest and the most important of the buidings in the temple complex.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

1.2.

According to historical sources from the Ming and Qing dynasties, such as the Guoque• (A Ming Chronicle), Mingshi (Ming History), Guangdong tongzhi: qianshi lüe• (Guangdong Records: A Sketch of Past Events) and Xiangshan xiangzhi• (Xiangshan County Records), the eunuch Li Feng was the most senior tax official of the Imperial Envoys to Guangdong from 1573 until 1620 (Wanli reign, year 27, month 2 - year 41, month 10). 5 Rong Houling• has done thorough research into the official duties for which Li Feng was responsible as Imperial Envoy in Guangdong. Today, judging from the historical evidence mentioned above and the inscription on the stone at the back of the shrine hall in the Temple of the Heavenly Princess, we know that while Li Feng was overseeing the building of the Temple to the Heavenly Princess in Macao, other than his duties as a eunuch, one of the highest-ranking officials of the time, his additional responsibilities as tax inspector for the Governor of Guangdong included supervising:

1. Pearl farms, located primarily in Lianzhou•, which produced pearls specially for the Imperial household,

2. The municipal fleet of ships, which were used to collect taxes from foreign trading vessels which came to China. At that time, a ship from Haojing was operated by a government office located next to the present-day site of the Ama Temple,

3. All tax-related affairs for the province of Guangdong, and

4. Salt taxation laws. The well-known Xiangshan saltworks were in Xiangshan county.

According to Mingshi: zinguanzhi - er• (Ming History: Officials - Part Two): "In the third year of the Emperor Wanli, the role of the Governor with jurisdiction over Guangdong was changed to include enforcement of the salt laws."

Clearly if Li Feng was described as "[...] Governor of Guangdong in charge of the salt taxation laws [...]," he must already have taken over the principle powers of office as provincial Governor of Guangdong. In fact, the authority of Governor still fell to Dai Yao, the Governor of Guangdong and Guangxi. The two facts that the building containing the shrine to the Heavenly Princess was built and consecrated by the eunuch Li Feng, Imperial Envoy and tax inspector for Guangdong, and, according to the stone inscription in the First Hall of the Holy Mountain, that the funds for building the temple were provided collectively by merchants of Dezi Street, we may conclude that this temple was built under official supervision but with funds provided by local businesses. Another look at the phrase "ruzai" in the inscription leads us to an entry in the Lunyu: ba yi• (Analects of Confucius: Eight Ranks): "The ruzai ceremony means to worship the gods as if they exist physically." This shows that the construction of the temple was conceived within the context of official orthodox Confucian doctrine. But on the two stone lintels in the First Hall of the Holy Mountain there are two separate inscriptions which read: "yingling xianying" ("Show due respect to the spirits of the departed") and "guochao sidian" ("Worship the Imperial Dynasty") (illustration. 5) All of these were carved when the temple was first constructed, and reflect the temple's official function as a place for offering sacrifices to the Imperial Court. The new temple to the Heavenly Princess (Lotus Temple), which was built slightly later near the custom house gate in Macao is a similarly jointly organised construction, built under official supervision but funded by local merchants. Both temples were built in the immediate vicinity of the local government offices and so were available to officials visiting Macao for use as temporary offices. As late as the reign of the Qing dynasty Daoguang Emperor (r. 1821-†1851), Lin Zexu made temporary use of the Lotus Temple and then went into the Ancestors' Hall in the Ama Temple to light incense and offer sacrifices when he visited Macao. 6 Both of these temples have the special political, religious and commercial significance which both of these temples have for Macao is obvious from this. These facts also provide sufficient evidence to disprove as erroneous recent suggestions that it was Fujianese shipping merchants who built the temple. 7 This misapprehension arose only since the recent immigration to Macao of large numbers of Fujianese merchants, who helped with the renovation and management of the Ama Temple. In fact, around the end of the Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Qing, the merchants of the shops and businesses in Macao's streets were mainly Guangdongnese or non-Chinese rather than Fujianese. This point is made in the Monograph of Macao: "The craftsmen, stallholders and shopkeepers are mostly Guangdongnese. They live in rented foreign houses, from where the tobacco smoke comes billowing down."8 This may be taken as additional evidence.

The same government officials whose main duties were to oversee the movement of traffic, shipping, trade and tax collection on the seas and rivers, were also responsible for overseeing the construction of the Ama Temple. This was the longestablished and traditional way of organising such a project; it was not a random ad hoc arrangement. For instance, the Haining xianzhi• (Haining County Records), fascicule 3, on Cimiao• (Ancestral Halls and Temples) notes that "The Temple to the Heavenly Princess in Haining***• consists of ten temples, built collectively by many different households."

The Haining xianzhi (Haining County Records) from Kangxi reign, year 14 (1676) state that: "[...] in the early Ming dynasty, Imperial officials were spread far and wide and each built a temple to the Heavenly Princess."9 Huang Keqian• writes in Hangzhou Youwei suo tianfeigong ji (Notes on the Temple to the Heavenly Princess at Youwei in Hangzhou) that: "All those employed by the military were engaged in transporting materials along the waterways for the construction of the Temple to the Heavenly Princess."10 This had been common practice from the time of the Hongwu• Emperor [r. 1368-† 1399]. The construction of temples to the Heavenly Princess by government officials such as Zheng He• and Wang Guitong• was a practice which began as early as the reign of the Yongle• Emperor (r. 1403-†1425). 11 The Guangzhou government shipping authority and tax inspection departments were situated next to the Temple to the Heavenly Princess outside Guide men• (Guide Gate) in Guangzhou. 12 In Xiangshan county, in addition to the Temple to the Heavenly Princess which was built next to the government tax and customs offices during the Ming dynasty, there was a Temple built right in front of the Hepo's• office by Chen Yu •during the reign of the Hongwu Emperor (r.1368-†1399). 13 There were even statues of the Heavenly Princess built inside the government sea defence and tax offices, for example one was built during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor (r. 1506-†1522) by Sheng Shaode• and another built in 1546 (Jiajing reign, year 24) under the command of Tian Ni,• situated at the government boatyard where the boats to defend again pirates were constructed. 14 Further examples of temples to the Heavenly Princess built by officials during the Ming dynasty are recorded in Fujian Jilue• (Monograph of Fujian), fascicule 6, Cimiao (Ancestral Halls and Temples): "[...] on Patane• county in Xiangshan• prefecture the Temple to the Heavenly Princess was built by the people of the neighbourhood, with funds donated by the eunuch of the garrison, Chen Dao."15 This temple was built by officials under the guidance of eunuchs. In Qiangzhou shihuo (Records of Qiangzhou) from the reign of the Emperor Daoguang (r. 1821-†1851), it is recorded that: "In Wanli reign, year 25, dingyou,• the Tianhou miao• [Temple to the Empress] was built by merchants under the supervision of officials."16

§2.

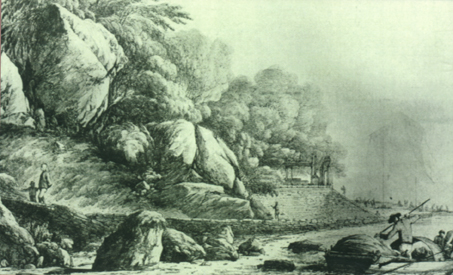

Where the hall with the carved stone plaque "Shenshan diyi"• ("First Holy Mountain") is today, there was originally an empty space more than three metres wide. This space separated two buildings, one in front and one behind. The one in front is the often-mentioned stone pavilion with carved stone inscriptions of literary texts which was built during the early Qing dynasty on the Ama Temple hill. (illustration. 6) Quotations from the reign of the Emperor Qianlong such as Zhang Daoyuan's:• "Far away from the Lotus Island is a pavilion made of natural stone [...]," Ximi Yang'a's:• "The Lotus island floats in the distance, the temple facing up towards the clouds [...]," and Zhao Yuanru's:• "Inside the temple is the First Hall of the Holy Mountain" all go to prove that until the end of the Qianlong period the Temple to the Heavenly Princess that people saw still consisted mainly of only one building. (illustration. 7) In one painting by the Western artist J. Webber of the Ama Temple seen from the side, the first building seen after entering the gate to the temple site was a pavilion style building without side walls. (illustration. 8) It was probably not until substantial alterations were made in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 8) that it was connected to the shrine hall behind to form the single building which is seen today. This modification was carried out by adding two decorative carved screens to in the spaces between the pillars at the sides, while the space between the central pillars was filled with a low fence-like wall with a gate in it. Finally, connecting walls were built on both sides of the empty space between the pavilion and the shrine hall, and a tiled roof was constructed on top. By viewing the temple in its present-day state from the side, this unusual structure can be made out quite clearly, as the roofs on the front, middle and rear sections are all different: at the front is the pavilion roof, at the back is the shrine hall roof, both of similarly complex design. But the roof in the middle is just a simple pyramid shape, obviously built at a different time. Likewise, the side walls of the three separate sections are all different: at the front are twenty-one window frames with carved screen panels, arranged in three rows, taking up all the space between the base of the wall and the roof beam. It is clear that this pavilion with windows for walls was not there originally. At the back there is a stone wall without windows which is much narrower than the front and middle sections (it is set back about one metre), which is an indication that in its original form the shrine hall had a separate stone wall, because the inner face of the wall is covered with engravings of ancient religious images. The middle section is of small bricks, with a square central window in four cut panel sections. The panels are the same as those in the pavilion at the front, suggesting that the two were installed at the same time. (illustration. 9)

Illustration. 8

The Ama Temple.

J. WEBBER.

This nineteenth century pencil drawing clearly depicts the first building behind the Shanmen• (Hill Gate) as a pavilion style structure with no side walls. The sketch was done in the late eighteenth century, and is one of the earliest known Western pictures if the temple according to Xu Xin's• The Ama Temple of Macao in Western Art. It is kept in the Jia Mei shi bowuguan• (Jia Mei shi Museum), at Fundação Orient (Orient Foundation), in Macao.

Illustration. 8

The Ama Temple.

J. WEBBER.

This nineteenth century pencil drawing clearly depicts the first building behind the Shanmen• (Hill Gate) as a pavilion style structure with no side walls. The sketch was done in the late eighteenth century, and is one of the earliest known Western pictures if the temple according to Xu Xin's• The Ama Temple of Macao in Western Art. It is kept in the Jia Mei shi bowuguan• (Jia Mei shi Museum), at Fundação Orient (Orient Foundation), in Macao.

Illustration. 9

Side view of the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The earliest Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess) was a simple construction and small in size. Its major component was the shrine built under the supervision of the eunuch Li Feng and the First Hall of the Holy Mountain which was contributed by the merchants of Dezi Street. The present-day form of the temple clearly shows how its front elevation consists of four pillars on a single base which was originally separated from the shrine hall behind by an empty space of about three metres.

The subsequent alterations are simply a a low fence-like wall with a gate in it between the pillars on the front façade and walls consisting mostly of decorative carved screen panelling. Finally, connecting walls were built on both sides of the empty space between the pavilion and the shrine hall, and a tiled roof was constructed on top, so the overall effect was of another small temple hall.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 9

Side view of the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain).

The earliest Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess) was a simple construction and small in size. Its major component was the shrine built under the supervision of the eunuch Li Feng and the First Hall of the Holy Mountain which was contributed by the merchants of Dezi Street. The present-day form of the temple clearly shows how its front elevation consists of four pillars on a single base which was originally separated from the shrine hall behind by an empty space of about three metres.

The subsequent alterations are simply a a low fence-like wall with a gate in it between the pillars on the front façade and walls consisting mostly of decorative carved screen panelling. Finally, connecting walls were built on both sides of the empty space between the pavilion and the shrine hall, and a tiled roof was constructed on top, so the overall effect was of another small temple hall.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

§3.

An inscription was discovered on the stone pillar on the right hand side of the stone shrine in the Hongren dian (Hall of Great Benevolence), which reads: "The auspicious day in the midsummer month of Daoguang reign, year 8 [1828], wuzi."• (illustration. 10) On the pillar to the left the inscription is: "Rebuilt respectfully by the grace of Zheng Shutang."• These characters were originally covered up by hanging brocades and could only be seen once these were removed, so in the past people have been unable to see them or comment on them. The date of the construction of the stone shrine and the date on the sign at the entrance into the hall indicating when the hall was rebuilt are identical, so it would seem possible to infer from this that the inclusion of the word "Rebuilt" on the sign in the hall refers to the renovation of the entire temple. (The same date is also recorded in other places, for instance on the stone balustrade which originally surrounded the main entrance and on the most important of the shrines to Guanyin.)• It does not mean that the hall was older and was renovated separately at this time, since there cannot have been a time when only the hall existed and not the shrine. This disproves the currently held idea that the Hall of Great Benevolence is the oldest part of the Ama Temple. One scholar has said that: "The phrase "hongren"• ("Great Benevolence") in the name of the Hall is a title of respect used during the Ming dynasty. [...] In Yongle reign, year 7 [1409], the temple was dedicated to the "Heavenly Princess Who Watches Over the Country and Cares for the People, Who is of Mysterious Efficacy, Clear Responsiveness, Great Benevolence, and All-Encompassing Aid." This dedication was made as a Memorial to the Emperor on Zheng He's return from his first visit to the West. At the same time as this dedication, an enormous temple to the Heavenly Princess was built overlooking the Longjian• (Dragon River) outside the Yifeng men• (Yifeng Gate) in Nanjing•, which was formally named "Palace of the Heavenly Princess, Who is of Mysterious Efficacy and Great Benevolence."[...] This enables us to deduce that the Hall of Great Benevolence must have been constructed later than Yongle reign, year 8 [1410]. The events which led from the initial dedication of the temple to the Imperial household up to the time when the temple was constructed and the plaque with the temple's name was chosen were all part of a single process. Yet in this case, the Imperial dedication was made in 1409 (Yongle reign, year 7) but it was not until either the Chenghua period [r. 1465-1†1487] or the Hongzhi reign, year 1 [1488], some fifty to eighty years after, far away from Nanjing in Macao, that the Hall of Great Benevolence was privately built. The facts are simply incompatible."

Another scholar has written in support of this idea that: "The construction of the Hall of Great Benevolence is popularly believed to have taken place during the reign of the Chenghua Emperor Xianzong• [r. 1465-†1487] or the first year of the Hongzhi Emperor Xiaozong• [r.1488]. Although this time frame does not necessarily encompass the exact date when the Hall of Great Benevolence was built, it cannot be far off. This is the author's own conclusion drawn from the choice of words "hongren" ("Great Benevolence") in the name of the temple."17

It is quite illogical and somewhat risky to set about calculating the date of the Hall of Great Benevolence's construction on the basis only of a likely earliest date but without defining a latest possible date. By this methodology, we could conclude similarly that the Temple of All Encompassing Aid was built during the Chenghua period (r. 1465-†1487) or in the first year of the Hongzhi Emperor's reign (r. 1488-†1505), just because when the temple was dedicated in 1409 (Yongle reign, year 7) and the dedication included not only the words "hongren" ("Great Benevolence") but also "puji"• ("All Encompassing Aid"). We might argue on the basis of the above argument that while the Chenghua (r.1465-†1487) or Hongzhi Emperors' periods might not fix the date of the construction of the Hall of Great Benevolence exactly, they are not wildly inaccurate, and we could go on to deduce from the latter argument that the Temple of All Encompassing Aid was built around the same time as the Hall of Great Benevolence. Using the same logic, we could conclude that any temple named after the Heavenly Princess in Macao or in any other place must have been built around the same time as the Temple of All Encompassing Aid and the Hall of Great Benevolence, because the last words in the temple's formal name in the dedication made in 1408 (Yongle reign, year 7) are "tianfei" ("Heavenly Princess"), and so they ought to be just as effective a method of proof as the word "hongren" ("Great Benevolence"). Carrying the same logic yet further, we might, on the basis of instances of temples being dedicated to the Heavenly Princess as early as the Yuan• dynasty18 (1206-1368), conclude that temples of this name were all built in the Yuan dynasty. And we might go on to say that since the Heavenly Princess was originally known as 'Ma'• ('Mother') or 'Mazu'• ('Ancestral Mother'), the name 'Mazu ge' (miao) ('Ama Temple') on the temple gate must be the oldest of the buildings in the temple complex and must predate the Hall of Great Benevolence by at least five hundred years. Naturally, this sort of reasoning does not stand up to logical scrutiny, just as we cannot use the fact that Yao, •Shun• and Yu• are among the oldest Chinese names to reason that people with these characters in their names were born earlier than people without these characters in their names. If we wish to know if one person was born earlier than another person, and do not have access to accurate records, the key method is to work out the latest possible year of birth, after which it is known that the person in question must have been born before that year. But whether it be a matter of people or of temples, it is generally very difficult to determine any date limit, be it earliest or latest. Although the temple dedication the "Heavenly Princess Who Watches Over the Country and Cares for the People, Who is of Mysterious Efficacy, Clear Responsiveness, Great Benevolence, and All-Encompassing Aid." was used for the first time in the Ming dynasty, in 1409 (Yongle reign, year 7), the name Heavenly Princess was in fact used again in the Qing dynasty, in 1681 (Kangxi reign, year 19). 19 Clearly, only if there were evidence to show that the Imperial Court forbade its use from a certain year onwards would it be possible to make use of this name to fix a latest date; otherwise it has to be admitted that any temple built after 1409 or indeed after 1681 might have a formal name containing these words, which might apply either to a whole temple complex or to a single hall or temple within it. Then again, the reasoning described above entertains no more than the possibility of inferring the earliest possible year in which the Hall of Great Benevolence could have been built, and fixes it as 1409. But why does this researcher make no attempt to determine a latest possible date? The reason is that it is impossible to make any reliable deduction from this evidence. According to the available sources, the Hall of Great Benevolence was constructed in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 8), so if the researcher can prove that the Hall of Great Benevolence came into existence as a result of renovations to an older Hall of Great Benevolence, then it would be known that the Hall of Great Benevolence must have been constructed before 1828 at the very latest. However, at present there is no evidence to support the idea that any building called the Hall of Great Benevolence existed prior to 1828, and so it will never be possible to prove false the current false assumption that the Hall of Great Benevolence in its presentday form is a reconstruction of an older Temple of Great Benevolence. Consequently, it is also impossible to substantiate the latest possible date of construction suggested above. But some time after 1828, the stone name plaque bearing the name of the "Hongren dian" ("Hall of Great Benevolence") was installed inside the Ama Temple, supposedly in 1488 (Hongguang• reign, year 1), and it is on the basis of this evidence that we can see that in 1912 (the first year of the Republic of China) Wang Zhaoyong's• memory was at fault. Wang Zhaoyong's mistake can be found out by looking in detail at the fourth part of his normally expert analytical reasoning. Briefly put, at no time during the history of the Ama Temple did there ever exist an earlier building called the "Hongren miao" ("Temple of Great Benevolence"). It is not possible to deduce the earliest possible date of construction from a non-existent building, much less to infer the date of the whole temple from this. In other words, this tells us that the researcher must be mistaken. Naturally, if we were to change our approach and investigate the issue of when the Hall of Great Benevolence was built, we would have to discover whether the Hall of Great Benevolence is older or more recent than the First Hall of the Holy Mountain or the shrine hall. We would have to reject Wang Zhaoyong's reasoning as false before beginning any valid comparison, and then look a route which might lead to an accurate solution of the problem. As stated earlier, there is both circumstantial and objective evidence to suggest that the First Hall of the Holy Mountain was built in 1605 (Wanli reign, year 33, yisi) of the Ming dynasty, while evidence of a similar weight can be brought to bear to suggest that the Hall of Great Benevolence was built in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 7, wuzi) of the Qing dynasty. Since the former was the principal and fundamental structure of the Ama Temple when it was first built, the latter is an additional building which was constructed as part of the subsequent development and expansion of the temple complex.

§4.

Wang Zhaoyong recalls that in 1911 he saw a stone sign at the entrance of the Hall of Great Benevolence inscribed with the "Hongguang reign, year 1" (1488). This idea is wholly a figment of Wang Zhaoyong's imagination, or else a false memory or fabrication, but has nonetheless had a profoundly adverse effect on subsequent research. Even today there are a number of scholars who have been led to draw erroneous conclusions on the basis of this information. There is ongoing debate on the issue, more than just taking for granted what the experts have to say. In fact, from looking at and analysing actual objects on site, we know that from the time of the inscription of the tablet carved with the name of the Hall of Great Benevolence in "Daoguang reign, year 8 [1828], wuzi" until today, there simply cannot have existed a different hall of Great Benevolence dating from "Hongguang reign, year 1", predating the stone plaque on the Hall of Great Benevolence. In 1911 Wang Zhaoyong simply cannot have looked at the place where the Hall of Great Benevolence is located today and seen a tablet bearing the date "Hongguang reign, year 1". What he could have seen might in actual fact be the stone tablet from "Daoguang reign, year 8, wuzi" which we can see there today. (illustration. 11) Just as he misread the date of the "Jinghai" inscription from year guimao• to year renzi• (this slip is recounted in §5. below), in this case he has incorrectly used the word "miao" ("Temple") instead of "dian" ("Hall") when referring to the Hall of Great Benevolence, and furthermore has wrongly stated that the stone tablet dates from "Hongguang reign, year 1" in the Ming dynasty and not from "Daoguang reign, year 8" in the Qing dynasty. In fact, if one deliberates slightly further, one can deduce that it is impossible for this temple to have a stone plaque inscribed with "Hongguang reign, year 1". If such a tablet existed, it could not have been preserved throughout the whole of the Qing dynasty. because Hongguang is the title of the reign of the acting Emperor of an Imperial Court in a small enclave of Ming authority in Nanjing which resisted the Qing dynasty. This Court existed for a period of only five months, approximately from February to June of 1645. For this reason, is it highly doubtful that the title of this Emperor's reign could have become known in Macao so quickly and then used immediately on a stone tablet of the Temple of the Heavenly Princess. Even if the title of this Emperor's reign were inscribed on the stone, at a time during the early years of the Qing dynasty when anti-Qing feeling was brutally suppressed and movements to throw out the Qing and restore the old Ming dynasty were put down, the Qing government officials in Macao would never have allowed a tablet with the name of this Emperor to be hung in a temple, let alone leave it there until 1911 to be seen by Wang Zhaoyong. Still more unbelievable is the suggestions that this stone tablet should have inexplicably and mysteriously vanished, having allegedly survived intact through the Qing era and beyond into the twentieth century, more than ten years into the Republican period, although no major mishaps befell this or any other building in the temple during this time. The weird and wonderful stories surrounding the bizarre fate of this stone carving are all the testimony of one man - Wang Zhaoyong. Why are they not corroborated by anyone else? It is clear that the description of this stone carving is either an honest mistake or of sheer fabrication on the part of Wang Zhaoyong and that it never actually existed. Whether mistake or invention, this amounts to uncommonly eccentric behaviour for a historian, quite outside the bounds of conventional research practices. Even though researchers were already aware of the flaw in his argument, when they drew attention to it, they were only ever bold enough to say that the mistake was a trivial one, that he had mistakenly recorded "Hongguang reign, year 1" instead of "Hongzhi reign, year 1." The reticence of Wang's critics makes the effects of his mistake difficult to rectify, and in fact simply adds to the general muddle. 20 Wang adopts the same disastrous approach as Fang Kuanlie's• mistaken attempt to clarify the date when the "Jinghai" carving was made, recounted below. It is difficult to imagine that wild errors such as these might issue from the pen of a distinguished scholar of Wang Zhaoyong's calibre, but these are the facts, and while they are a source of heartfelt regret for me, they must be stridently and absolutely refuted. Reportedly: "At present, certain people in Macao maintain that the Hall of Great Benevolence, the oldest building in the Ama Temple, was built in Hongzhi reign, year 1 [1488], so construction was begun during the Chenghua period [r.1465-†1487], of the Ming dynasty more than five hundred years ago."21 If the Hall of Great Benevolence is the oldest building in the Ama Temple complex, it would logically date from the time when the temple was first constructed, but those who support this line of thinking also say that the whole of the temple was built at least one year earlier than the Hall of Great Benevolence. This is clearly an attempt to reconcile the "Chenghua period" 'theory' with the "Hongzhi reign, year 1" 'theory', though the only result is a self-contradiction which does not hold water.

So, is it really possible to continue to believe 'recorded fact', namely the false supposition that the Hall of Great Benevolence is the oldest of the temple buildings, built earlier than the First Hall of the Holy Mountain and Li Feng's shrine, and that the inscribed stone tablets recording the building dates were destroyed at the time of the renovations in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 8)? The author has undertaken exhaustive research into this matter and found this deduction to be quite untenable, for the following reasons:

1. As argued in the § 1. above, if the Hall of Great Benevolence were the part of the temple which was built earlier than the First Hall of the Holy Mountain and Li Feng's shrine, then the relevant stone inscriptions on both of these buildings and the records in the Monograph of Macao would show different registers. That this is not the case constitutes counterevidence to suggest that the Hall of Great Benevolence must have been built later than the First Hall of the Holy Mountain, funded by the merchants of Dezi Street, and later also than the shrine built by Li Feng.

2. If the Hall of Great Benevolence were the earliest of the main temple buildings, then the stone tablet on the First Hall of the Holy Mountain would not have been carved in the doorway of this hall, but rather in the doorway of the Hall of Great Benevolence. Similarly, the early Qing poetry inscription would not refer mainly to the First Hall of the Holy Mountain, but would be concerned only with the Hall of Great Benevolence. This serves to show that what these poets saw at the time was the First Hall of the Holy Mountain and not the Hall of Great Benevolence.

3. If the existing stone plaques dating from the time of the original construction were not destroyed at the time of the rebuilding in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 8), then judging from the inscription on the stone plaque on the First Hall of the Holy Mountain, there would be a record first of the year of the original construction and then the year of the reconstruction. But the date of construction which can be seen on the pillar at the side of the shrine and the rebuilding date on the tablet over the main door are one and the same: "Daoguang reign, year 8 [1828], wuzi", which shows that the people who carried out the renovation inside and out were unaware of any hall or shrine which existed before, or else they would surely have indicated the date of construction of the earlier building.

4. The shrine in the hall and the shrine built by Li Feng are similar, but the inscriptions bearing the names of the people who built them are different. There is only the carving on the left side pillar bearing the name "Zheng Shutang" and the date of the shrine's construction as "Daoguang reign, year 8, wuzi" on the right side pillar. As discussed earlier, this evidence proves conclusively that this shrine built in 1828 was an imitation of Li Feng's shrine, and proves also that the Hall of Great Benevolence, which honours this shrine, was built in the same year.

§5.

Zhang Yinglin's• (alias Zhang Yutang•) cliffface inscription of the characters "Jinghai" was carved in Daoguang reign, year 23 [1843], guimao in the Ming dynasty. (illustration. 12) Wang Zhaoyong's theory that it was done in "Daoguang reign, year [?], renzi" had been current since the early years of the Republican era, but as has been pointed out by Fang Kuanlie, there was no year renzi in the Daoguang period, so Wang Zhaoyong's theory must have been false. But "Xianfeng• reign, year 2 [1852], renzi", put forward by Fang Kuanlie as an alternative, is also obviously a mistake which has not been properly thought through. 22

§6.

The Mazu ge (miao) (Ama Temple) in its present-day form is an amalgamation of two temples built in different dynasties by different people. The earlier part was the Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess), made up of the shrine built in the Ming dynasty by the eunuch Li Feng during the Wanli period (r. 1573-†1620) and the Shenshan diyi (First Hall of the Holy Mountain) built by the merchants of Dezi jie (Dezi Street). The later part was the Tianhou miao (Temple to the Empress) - which is the part of the temple known today as the Zhengjue chanlin (Zhengjue Temple) - built in the Qing dynasty mainly by Fujianese merchants who came to live in Macao and by officials. (illustration. 13)

§7.

Since this Temple to the Heavenly Princess was jointly built under the supervision of officials with funding provided by local merchants, it became a temple which was part of the official network of Imperial ceremonial worship, and was not merely privately built by local merchants and businessmen and named Ama Temple by them. The temple's official name, as is recorded in the Monograph of Macao, was therefore "Tianfei miao" ("Temple to the Heavenly Princess"). (illustration. 14) The alternative names "Mazu ge" ("Ama Temple") or "Ma ge (miao)" (Guandongnese: "Ma Kok Miu")• were substituted by Fujianese residents who took charge of the temple during the Qing dynasty. (illustration. 15) Some researchers today have not distinguished the actual historical facts from the traditionally believed legends of the temple's past, assuming "Ama Temple" to be the original official name, and "Temple to the Heavenly Princess" to be a later popular name. The same sort of deduction has misled people into thinking that the Portuguese name 'Macau' is derived from the Guandongnese name 'Ma Kok Miu'.23 Early Portuguese sources mention that the origin of the name Macau derived from the name of a Chinese goddess, namely "Ma" ("Mother") or "Yama" ("Ancestral Mother") and not, as was the subsequent erroneous belief, from the name of the mother of god, the madonna of Western Catholicism, or from the name of a Chinese temple, "Ma Kok Miu." Dai Yixuan is able to point out that: "The name Macau cannot be derived from Heung Ma Kok• or Ma Kok.• In the nineteenth century the name of the Ama Temple was translated into English as "Amakok Temple", where kok is used to transcribe a character pronounced with a final consonant -k."24 The pronunciation was not rendered as Amacao. For this reason, I agree with the idea usually put forward by Western writers that "Amacao" is a Guangdongnese transcription of "A Ma Ngou"• ("Ama Bay"). The first full names that the Portuguese colonialists gave Macao were Povoação do Nome de Deus de Amacao na China (The Settlement of the Name of the God Amacao in China), Porto de Nome de Deus (Port of the Name of God) and Porto de Amacao (Port of Amacao). 25 Therefore, it can be proved using both Chinese and Portuguese sources that it is quite unfeasible to infer from the foreign names Macau or Amacao that the Ama Temple had already been built when Macao was first founded.

Illustration. 10

One of the inscriptions carved on the stone pillars of the shrine in the Hongren dian• (Hall of Great Benevolence).

The inscription reads:

"The auspicious day in the midsummer month of Daoguang reign, year 8, wuzi•"

[1828].

This fixes 1828 as the year in which the both the shrine itself and the whole of the Hall of Great Benevolence were constructed.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 10

One of the inscriptions carved on the stone pillars of the shrine in the Hongren dian• (Hall of Great Benevolence).

The inscription reads:

"The auspicious day in the midsummer month of Daoguang reign, year 8, wuzi•"

[1828].

This fixes 1828 as the year in which the both the shrine itself and the whole of the Hall of Great Benevolence were constructed.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 11

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the front entrance to the Hongren dian• (Hall of Great Benevolence).

The inscription reads:

"Daoguang reign, year 8."

It confirms that this is not the oldest building of the Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess), and also that Wang Zhaoyong's record of an inscription dated Daoguang reign, year 1 [1821] is an error.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 11

Inscription carved on the stone lintel of the front entrance to the Hongren dian• (Hall of Great Benevolence).

The inscription reads:

"Daoguang reign, year 8."

It confirms that this is not the oldest building of the Tianfei miao (Temple to the Heavenly Princess), and also that Wang Zhaoyong's record of an inscription dated Daoguang reign, year 1 [1821] is an error.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 12

Zhang Yutang's rock carving.

The inscription, carved in 1843 (Daoguang reign, year guimao), reads:

"Jinghai."

This clears up Wang Zhaoyong's long-standing but mistaken idea that it was 1852 (Dialoguing reign, year renzi), and also shows the folly of Fang Kuanlie's more recent suggestion of Xianfeng reign, year renzi.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 12

Zhang Yutang's rock carving.

The inscription, carved in 1843 (Daoguang reign, year guimao), reads:

"Jinghai."

This clears up Wang Zhaoyong's long-standing but mistaken idea that it was 1852 (Dialoguing reign, year renzi), and also shows the folly of Fang Kuanlie's more recent suggestion of Xianfeng reign, year renzi.

Photograph taken in December 1996 by Kuang Yaolin 邝耀林.

Illustration. 13

The front elevation of the Zhengjue chanlin (Zhengjue Temple).

The structure was built during the Qing Dynasty. Its main entrance is on the left of the façade.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 13

The front elevation of the Zhengjue chanlin (Zhengjue Temple).

The structure was built during the Qing Dynasty. Its main entrance is on the left of the façade.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

§8.

There are essentially three popular legends in China concerning the existence of the Ama Temple in its present-day form. These stories have evolved because of records created and disseminated by different people at various times.

8.1.

First is the story according to which the Temple to the Heavenly Princess was built during the Wanli reign. The earliest documentary evidence for this version of events is found in Monograph of Macao. The salient point is that the building of the temple was inspired by an appearance of the spirit of the Heavenly Princess during the Wanli reign (r. 1573-†1620). The Heavenly Princess in this story did not sail to Macao in a boat from Fujian. She appeared as a goddess on the mountainside to a merchant sailors coming from Fujian who were in danger from a storm which suddenly abated. This legend does not mention that the Temple to the Heavenly Princess was built by this merchant.

8.2.

The second story is that the temple was built in early Qing times by Fujianese immigrants. The earliest record of this story dates from "Daoguang reign, year 27" (1827), on the Monument erected to Commemorate the building of the Ama Temple at Haojing Bay in Xiangshan. The relevant point in this version of the story is that reference is made not specifically to the "[...] Wanli period of the Ming dynasty [...]," as above, but only to "[...] the Ming dynasty [...]." Furthermore, the Empress is described as the incarnation of "[...] an old woman who sailed one night from Fujian to Macao." Lastly the statue, the building of the temple and the monument are all attributed to "[...] Fujianese merchants resident in Macao."

8.3.

Thirdly, some people have been misled by Wang Zhaoyong's mistaken fable about the Hall of Great Benevolence dating it from "Hongguang reign, year 1" (1488). Using the second variant of the story above, they have found it easy to take advantage of the muddled flaws in the story in order to transpose it into a different era to suit their requirements. So what was originally "[...] the Ming dynasty [...]" now becomes "[...] the Chenghua period of the Ming dynasty [...]" or "Hongguang reign, year 1".

Of these variants, the most authentic and credible is the one which specifies "[...] the Wanli period of the Ming dynasty [...]," being the hardest to discredit. The other theories have been rejected for this reason. The activities held to celebrate the supposed five hundredth year of the Ama Temple and the erection of the Mazuge wubai jinian beiji (Monument to Commemorate the Quincentenary of the Ama Temple) were done in 1984 as a result of this same mistaken thinking. Now that this mistake has been enshrined in stone on this recent monument, this date has come to be generally believed, but is in fact sheer absurdity on a grand scale. Of the three possible dates which have been proposed for the building of the temple, the Chenghua period is the only one which is completely unattested in documents; it is something which people say having worked it out for themselves. The evolution of the stories relating to the Ama Temple recounted above is a typical example of the way different views of history can reveal errors in the accepted version, arrived at via accumulated strata of historical information. 26

§9.

Foreign language source materials relating to the history of the Ama Temple have been discovered. Among the many myths surrounding the building and subsequent development of the temple, one seems to have been completely ignored by Chinese people for more than a century, and so is only referred to by historians who have never entered China. As long ago as 1840, an article appeared in the English periodical "The Chinese Repository"•**** (vol. 9 October 1840) entitled Description of the Temple of Matsoo po, at Ama kǒ [sic - according to Tan Shibao] in Macao. This is earliest attested Western document on the topic. It is a relatively early source, but must have been well-known in Macao in 1840. The author's own research has shown that even this ancient source is merely another myth. This article's main account of the building of the temple stems from the historical fact of the arrival in Macao during the Wanli period of the Imperial Envoy, the eunuch Li Feng, to supervise the building of the Temple to the Heavenly Princess, and so it is of more value as a research tool than the other variants.

History has been muddled by various fictitious myths. In this case the story, a combined fusion of history plus myth, has long since been lost in China. While undergoing the complex process of dissemination and translation into English, and finally inclusion in "The Chinese Repository", some key elements came to be lost from the story: the name of Li Feng and also the original Chinese names of certain places and of officials. Even though some Portuguese researchers have had access to this material, no-one has yet been able to extract the true historical facts. For instance, in 1979 Fr. Manuel Teixeira combed exhaustively through some secondary sources, 27 but the story he came out with was both simplified and incorrect. 28 In a passage in the same book, Manuel Teixeira cites the entire story from an original source, but since it is without any analytical discussion, its exposure of the inherent contradictions is worthless. 29

In 1988, the Portuguese scholar Rui Brito Peixoto• published an article in the three languages, Portuguese, Chinese and English, entitled Art, Legend and Ritual: Pointers to the cultural identity of Chinese fishermen in the South of China but only told the first half of the story. To date, no-one has pointed out that the this version of the story is simply a reworking of the historical fact that Li Feng built the temple. It was only after discovering the stone inscription of Li Feng's name identifying him as the builder of the temple that the author went on to use this information to undertake analytical research, comparing all the documentary sources from beginning to end, and so discovered the inherent connection between the two. Manuel Teixeira's version is fundamentally inconsistent with the facts, so there is no point in subjecting it to detailed analysis. Since his book is essentially tourist literature concerned only with anecdotal stories about the Ama Temple for popular consumption, rather than a scholarly monograph of historical research standard, it does not scrutinise the origin or the reliability of the sources it uses and contains an amount of false information. For instance, his book mentions one "Emperor Sun-ke"•30 although no such Emperor existed in the Ming or Qing dynasties. In the original English account of the building of the temple, the relevant mention is of: "In the reign of Teenke• [...]." Manuel Teixeira's "Sun-ke" should read "Teenke". Similarly, he renders the "Kǒ" of the original as "Kó", and "Hǒ" as "Hǒ", all of which is indicative of a lack of meticulousness. Although I respect Manuel Teixeira as a venerable member of the senior generation, his book is clearly not a scholarly work, and so cannot be scrutinised as such. Even so, we would be well-advised to analyse and study it, since some of the material in the book can be assumed to be cited directly from reliable historical sources. However, some people seem still unable to understand the difference between historical scholarship and popular myth: when it comes to an academic discussion of the date when the Ama Temple was built, they cite blindly as fact some of the popular mythical beliefs and views in Teixeira's book and use them as historical evidence for the purpose of querying and contradicting the stone inscription of Li Feng's name and the record in the Monograph of Macao of the date of the temple's construction. It would be no less absurd to use the story of the novel Sanguo yanyi• (The Romance of the Three Kingdoms) to disprove the historical records of the Sanguo zhi• (Annals of the Three Kingdoms). Sometimes even the accepted opinion of experts is a mixture of truth and falsehood, while at the same time there are people more recently who tamper with the truth by passing off modem works as ancient texts. Fernão Mendes Pinto's Peregrinação***** (lit.: Pilgrimage, or The Voyages and Adventures [...]), a book which is highly implausible throughout, 31 also fails to examine primary sources thoroughly. A few phrases quoted directly from Manuel Teixeira's book are evidence of this. He writes: "In his travel notes [i. e., The Voyages and Adventures [...]], Pinto mentions that he has already seen the Ama Temple in Macao." This is tantamount to passing off another person's work as his own, a distortion of knowledge borrowed from the so-called scholars of thirty years ago. He treats information lifted directly out of Pinto's travel notes as if it were reliable evidence. In the context of today's more rigorous scholarship, it is surprising that this is still accepted as historical research. When this finds its way into the 'academic' columns of the periodical, it is enough to make one heave a sigh of exasperation. 32 On page seven of his book, Manuel Teixeira quotes from Charles Ralph Boxer's book Fidalgos in the Far East: "The picturesque temple dedicated to this Goddess at the entrance of the Inner Harbour is the oldest building in Macao, and is probably little changed from the time when Mendes Pinto first set eyes on it in 1555." This passage shows only that Manuel Teixeira and others like him think that Fernão Mendes Pinto and his compatriots saw the Ama Temple in 1555, but it cannot show that Pinto himself had already recorded having seen the temple in his travel notes. It is blatantly obvious to all that, whether in his letters or in his book The Voyages and Adventures [...], there is no single mention of Chinese temples in Macao. 33 One might well enquire what ingenious method enables Manuel Teixeira to make the fictitious deduction that: "In his travel notes, Pinto mentions that he has already seen the Ama Temple in Macao." The most dumbfounding thing of all is his attempt to prove the theory that the Ama Temple was built before 1500 is based on 'textual research' which is itself ridden with errors. At present, what needs most to be corrected is this bad academic practice, a mistaken tendency which threatens the development of research into Macanese history with serious impediment and folly. It is vitally important to scrutinise researchers into Macanese history and to verify the academic calibre of their work according to the criteria of the universally accepted rules and norms of Chinese and Western scholarship. These fraudsters must be stopped! 34

With the objective of excavating the real history behind the myths, the present paper offers a detailed discussion of Rui Brito Peixoto's scholarly work. What follows is a preliminary review of those parts of Peixoto's previously mentioned article which relate to the Legend of the Founding of the Barra Temple [Ama Temple]. [...].

Peixoto's work introduces four separate versions of The Legend of the Founding of Barra Temple two of which are not themselves clearly dated, but which can be traced respectively to Luís Gonzaga Gomes' A Lenda do Templo da Barra (The Legend of the Ama Temple) published in 1967 [ sic ?], ****** pp. 13-16, and Manuel Teixeira's Templo Chinês da Barra: Ma-Kok-Miu (The Chinese Temple of Barra: Ma-Kok-Miu), published in 1979. These two versions of the story are the modern reflexes of the legends recounted earlier, which first appeared during the Qing dynasty. The third and fourth versions are both stories from the Wanli period of the Ming dynasty and are recorded by writers active much earlier that the two just mentioned. The third version is recorded by Ying Guangren and Zhang Rulin and the fourth appears in the English edition of "The Chinese Repository" of 1840. By checking the original source, it emerges that the story Peixoto uses is part of a passage entitled Description of the Temple of Matsoo po, at Ama ko [sic - according to Rui Peixoto] in Macao, which is cited in the original as having been "Prepared for The Repository by a Correspondent".

This suggests that the article was compiled specially by a journalist for "The Chinese Repository", and so also that this must be the earliest mention of the story in a Western document. It can therefore be used to amend the various incorrect citations from it which have appeared since. This document does actually record the entire historical development of the temple built at the end of the Ming dynasty by Li Feng, which was expanded in 1828 (Daoguang reign, year 8) by Fujianese merchants to become the Ma Kok Miu (or Ma Tsou Po Miu).• Although between 1840 and the present day many foreign scholars of Macanese history must have read this text, not one of them has traced the historical progression from the original building to the subsequent renovation and expansion, for the following reason: when the historical facts of this story were embellished and even falsified by a corollary of myth and fantasy, the name of the key character Li Feng came to be omitted, and the date of the temple's original construction was changed from the Wanli period to a time five hundred years later. The fact of Li Feng's hand in the construction of the temple is, however, not attested in other historical sources, with the exception of the concealed stone inscription which was preserved in the temple but remained unnoticed by outsiders and has only recently discovered and brought to light by the author. So it is quite understandable that Manuel Teixeira, Rui Brito Peixoto and other Western researchers had no inkling of it. Adding to this their general unfamiliarity with names and places in Chinese history, which made it impossible for them to convert English translations into their original Chinese versions, there were serious obstacles which prevented them from extracting the truth from the stories. It must be conceded that while Peixoto's work contains errors, his record of Li Feng's construction of the temple is basically correct, an advantage which gave the author a considerable headstart in this research. It was only after reading Peixoto's work that the author associated the story with the newly discovered inscription identifying Li Feng as the builder of the temple, and so resolved to embark on a more detailed analysis of the original text. Now there is a need first to extract the story from the Chinese and English versions of Peixoto's writing and analyse it anew - this story is in fact the mythical vestige of the historical facts which failed to be handed down and so died out in China a long time ago.

§ 10. THE THREE STORIES OF HOW THE AMA TEMPLE CAME TO BE BUILT

"Legend of the founding of Barra Temple (3rd version)

In the reign of Wanleih, of the Ming dynasty (about AD 1573), there was a ship, from Tseuenchow foo in the province of Fuheën in which the goddess Matsoo po was worshipped. Meeting with misfortunes, she was rendered unmanageable and driven about in this state, by the restless winds and waves. All on board perished, with the exception of one sailor who was a devotee of the goddess, and who, embracing her sacred image, with the determination to cling to it, was rewarded by her powerful protectionm and preserved from perishing. Afterwards when the tempest subsided, he landed safely at Macau, whither the ship was driven. Taking the image to the hill at Ama ko, he placed it at the base of a large rock - the best situation he could find - the only temple his means could procure. About fifty years after this period, in the reign of Teenke, there was a famous astronomer, who from some correspondence (unknown to common mortals) between the gems of heaven and the jewels of the earth, had discovered that there was a pond in the province of Canton containing many costly and brilliant pearls, upon which he addressed the emperor, respectfully advising him to send and get them. His imperial majesty, availing himself of the important information, dispatched a confidential servant in search of this wonderful pond. On arriving at Macao, and passing the night at the village of Ama ko, the goddess appeared to the messenger in a dream, and informed him, that the place he sought for, was at Hopoo in Keaou chow or the district of Keaou. He went to the place and procured several thousands of the finest pearls. Glowing with gratitude for the secret intimations he had received, he built a temple at Ama ko, and dedicated it to his informant."

("The Chinese Repository", 1840, p.403)35

The Chinese version of the legend reads as follows:

“明朝万历年间(大约1573年), 有一条福建船, 船上供奉著妈祖神。这条船不幸失去控制,随风浪漂流。船上的所有人都被淹死,只幸存一个信仰阿妈神的船夫。船夫抱著圣像,决心死也不放弃她。他终于得到神的大力保护幸存下来,当风暴减缓时,他所在的船被拖到澳门,他安全无恙地上了岸。他把像带到阿妈山,把它放置在一块大岩石的基座尚(这是他能找到的最好的对方),这是当地环境所能提供的最理想建寺庙的对方。

大约过五十年,天启年间,有一个著名的天文学家,他通过天堂宝库和人间珠宝之间一种对应关系(凡人不知)了解广东省有一盛产珍稀发光的珠子的湖。因而他诚惶诚恐地向皇帝进言,力谏皇帝派人去取珍珠。皇帝陛下得知这一重要消息,就派一名忠诚的仆从去找那美妙的湖。当他到达澳门时,这位钦差在阿妈角过了一夜,他在梦中见到女神,女神告诉他,他寻找的湖在Keaou chow(或Keaou县)的Hopoo。皇帝钦差朝著女神指引的对方去了,果然他造那里找到数以千计的最精美的珍珠。为了感激他曾获得的神秘启示,在阿妈角兴建了座寺庙,供奉这一消息的提供者。”36

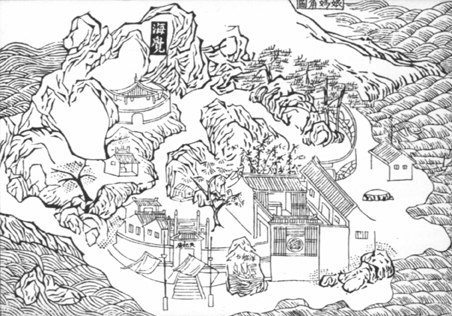

Illustration. 14

Illustration of "Niangma Jiao"• from the Aomen Jilue (Monograph of Macao).

The inscription on the gate of the temple reads: "Tianfei miao."

The temple known today as the Mazu ge (Ama Temple) was called the Temple to the Princess of Heaven during the Ming dynasty.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao谭世宝.

Illustration. 15

Entranceway into the temple of "Mazu ge" ("Ama Temple").

The inscription over the doorway reads: "Mazu ge."

This has convinced some people that the temple was built by Fujianese, that the temple was therefore also called Mazu ge in the Fujianese tradition, and that this was the temple's popular mane. The opposite is in fact the case: the temple was originally built by the Imperial authorities with the cooperation of local merchants, so the official name Mazu ge must have been agreed by the Ming authorities. The popular Fujianese name Mazu ge can only have been adopted s the temple's official name after Fujianese took over the administration of the temple during the Qing dynasty.

Photograph taken in 1996 by Tan Shibao 谭世宝.

Illustration. 16

Statue of Li Feng.

The head of the statue was broken off in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution campaign to "Smash the Four Olds".

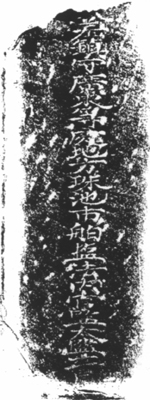

Illustration. 17

Rubbing of the inscription on the reverse of the Li Feng statue.

The statue was originally on the east side of the Six Banyans Pagoda in Guangzhou, in a shrine to Buddha which is devoted the Guanyin.

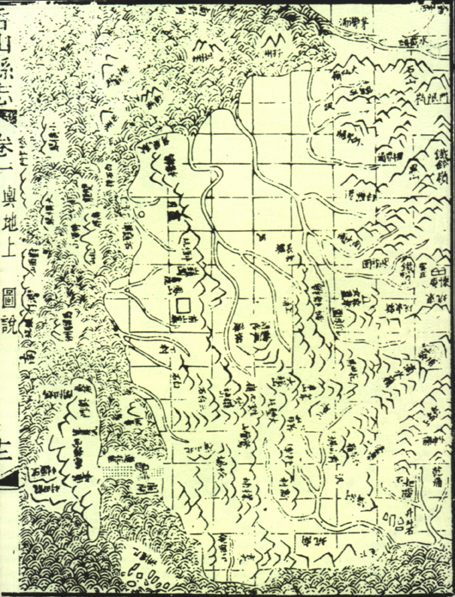

Illustration. 18

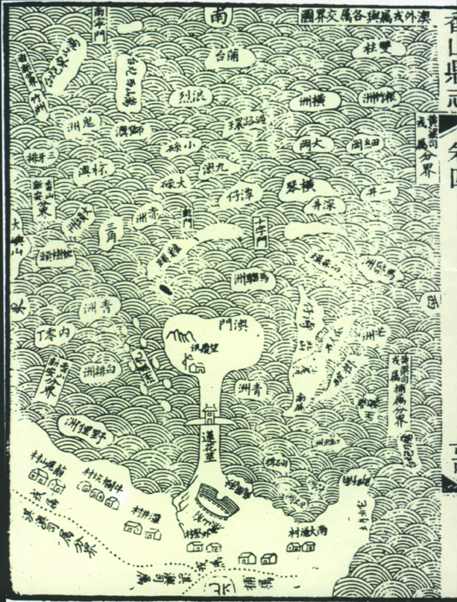

Macao and the neighbouring territory of Jiu (xing) zhou.• In: Xiangshan xianzhi (Xiangshan County Records). , fascicule 1-From the Daoguang period.

IN the lower left hand corner near to "Jiu (xing) zhou", "Aomen" ("Macao") is marked as just a place name on one edge of the peninsula, just to the north-east of "yiju"• ("foreign residences")and "Mazu ge"("Ama Temple").

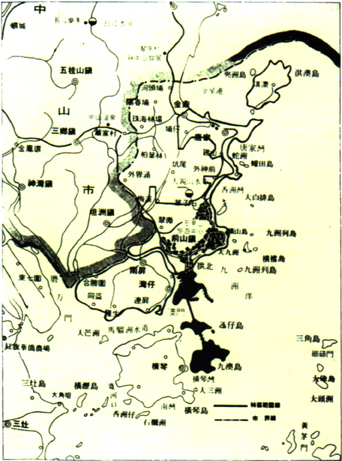

Illustration. 19

Map of military possessions and boundaries with other territories.

IN: Xiangshan xianzhi (Xiangshan County Records), fascicule 4-From the Daoguang period.