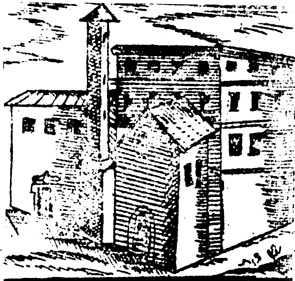

The Namban-ji(Temple of the Southern Barbarians) - fan painted by Kano Motohide, depicting the Jesuit church built in Kyoto in 1576.

The Namban-ji(Temple of the Southern Barbarians) - fan painted by Kano Motohide, depicting the Jesuit church built in Kyoto in 1576.

"Six o'clock in the evening, the twenty fifth day of the eighth month in year eleven of Tenmon; a great ship arrived at Nishimura beach, on our island of Tanega, with more than one hundred people on board. Their language was incomprehensible. One of the crew was a Chinese confucianist scholar called Goho. A certain Oribenojo, head of Nishimura village, understood Chinese writing. He met Goho on the beach and using a stick he wrote on the sand:

- "From what country do those strange men on board hail?"

- "They are "Namban", Southern Barbarians. Despite the fact that they are either lords or their vassals, they behave in much the same way, and their behaviour and manners leave much to be desired. So, when they drink, they drink a lot but they do not use cups. When they eat, they eat with their fingers and do not use chop sticks. They follow only their emotions and know nothing of the wisdom of moderation. Furthermore, it is said that when the barbarians arrive anywhere, they immediately decide to stay there. Judging by what they have brought, they trade only in what the natives lack. They are harmless people from whom we have nothing to fear." (1)

This is how Nampo Bunchi (1555-1620), a Zen priest from Satsuma prefecture relates the story of how the Portuguese, the "namban", Southern Barbarians arrived in Japan. More precisely, they arrived on Tanegashima Island, one of a group of islands to the south of Kyushu. The Teppo-Ki (Musket Chronicle) was written at the request of the Lord of Tanegashima, Tanegashima Hisatoki, to keep alive the memory his grandfather Tokitaka. The description left by that priest is a very valuable piece of information.

News of the arrival of these strange people was taken to Tokitaka, lord of the island. He sent twelve rowing boats to tug the junk into Akaoji harbour.

"On board were two "namban" officers. One of them held an object two or three "shaku" long in his hands..."(2)

This object excited the curiosity of the islanders. After it had been demonstrated a few times, they looked as if they wanted to find out how to use it. Tokitaka ordered the barbarians to be brought before him and told them:

"I can't say I am well acquainted with this object: so I would like to learn more about it."

"If your Lordship wishes to learn, we shall do our best to teach you."

"Do you think I could learn its secrets?"

"Only if you can purify and cleanse your mind, and have a steady eye."

"Clean thinking is the teaching of the ancient wise men and I was educated accordingly. If we cannot raise our thoughts above the heavens, then our words and actions shall be contrary to our own opinions. What you speak of must be the same principle. But it is not enough to have only one steady eye to see far and wide. Why do you make one of your eyes steady?"

"You must see clearly. It is not enough to see over a wide range in order to see clearly. To see things clearly, your eye must be very sharp. Your eye is trained to see clearly over a long distance. Please try to learn this."

"Loa-Tse said that to observe a little is to see better. Is this the principle of which you speak?"(3)

This was how not only Tokitaka but all the Japanese learnt the secret of how to use a musket, the forefather of the shot-gun and the symbol of the West's technological advance on the Orient. This exchange between the Southern "Barbarians" and the lord of the isle introduced the Japanese to new military strategies which helped in bringing to an end the bloody civil wars which had ravaged the Japanese archipelago. The unification of Japan which Oda Nobunaga, and most of all Hideyoshi Toyotomi, achieved was most definitely due to the introduction of the shot-gun into the Japanese army by the Portuguese.

In 1543, the Portuguese reached the Land of the Rising Sun. This was the result of the natural progress of their voyages on the high seas, voyages which had begun over a century before with their arrival at the Atlantic islands.

Sixteenth century Portugal was living on the high of the Discoveries, the opening up of new continents. Their entry into the Indian Ocean destroyed Ptolomy's old theory that "the Indian Sea was just like a lagoon, set at a great distance from our Western Ocean by southern Ethiopia; and between the two seas there is a strip of earth to prevent any ship from getting past the Gulf of India..." as Duarte Pacheco Pereira tells us in his logbook Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis.

Once the Portuguese had arrived in India, they opened up the trade routes to the Orient, making Lisbon the port of the world. There was a hive of activity between the capital of the new empire and India, the central producer of spices, over which the Portuguese Crown had exclusive control.

Portuguese ships crossed the seas and anchored in distant harbours where they founded trading posts for exchanging goods. A very active trade route was established stretching from the western coast of India past Goa, Malacca and the Moluccas as far as China. Portuguese domination of the sea had reached Asia.

Ming dynasty China had abandoned its policy of maritime expansion and Admiral Zheng He's flag no longer fluttered in the China Seas. There is no obvious reason why this policy should have been dropped although attacks from the "dwarf-pirates" (wakos) from the Ryuku Archipelago in Japan and the insecurity caused in the North by the Mongolians and Manchu nomads may have had something to do with it.

We find the first Portuguese reference to Japan in Tomé Pires' Suma Oriental, written in Malacca between 1513 and 1515.

"From what the Chinamen say, the island of Japan is bigger than Ryuku and the King more powerful and great. He is not given to trading nor are his subjects. The King is a vassal of the King of China but they have little contact with China for it lies at a great distance and they have no junks, nor are they seafarers.

The Inhabitants of the Ryuku Islands can reach Japan in seven or eight days and take merchandise which they exchange for gold and copper. Everything which comes from the Ryuku Islands is taken by their inhabitants and they trade fishing nets and other goods with the Japanese."(4)

At that time, the Land of the Rising Sun was going through the difficult "Sen-koku-jidai" (Warring Country Era) which was marked by a weakening in the emperor's personal power and constant struggles amongst the restless feudal nobility to gain land and power.

Fernão Mendes Pinto, one of the most eclectic men of his time - adventurer, merchant, soldier, sailor, missionary and writer - believed to be one of the first three Portuguese men to have set foot on Japanese soil, described the arrival of the Portuguese in Japan in the most exotic and expressive prose in Peregrinação, "a unique, quixotic, extravagant and passionate book".(5)

"After a great storm, Our Lord came to our succour and we caught sight of land. When we drew up near to see if there was any sign of a bay or port where we could anchor, we saw a great fire to the South, almost on the horizon of the sea, which we thought must be inhabited by people who would give us water, which we were sorely lacking, in exchange for our money. When we got close to the edge of the island, two narrow boats with six men came out to meet us. When they came on board, they greeted us in their traditional way and then they asked us where the junk came from the which we replied from China and that we were carrying goods which we wanted to trade with them if they would allow us. One of them replied that the lord of Tanishuma Island would happily give us the license if we paid the taxes which were customary in Japan, that great land which spread before us... We had been in that little bay at Miaijima for less than two hours before the prince of the island of Tanishuma came out to our boat... and seeing we three Portuguese he asked what kind of people we were for from our different faces and beards he could see that we were not Chinamen. The buccaneer captain answered that we were from a land called Malacca where we had arrived many years previously from another country called Portugal whose king, according to what we had heard a few times, lived in the height of grandeur. At which the prince took great fright and said to the men around him:

Let me be struck down if these are not the very same men mentioned in our tomes who, flying over the water, have dominated the inhabitants of the lands where God created the wealth of the world and who will bring us luck if they come to us in the spirit of friendship... "(6)

This beautifully illuminated document is the famous letter of introduction dated April 1588, from Dom Duarte de Menezes. Viceroy of India addressed to Toyotomi Hideyoshi who had ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits. It was presented in person by Father Alexandre Valignano of the Jesuits in Kyoto on the 3rd of March, 1591. (60.6cm x 76.5cm, Kyoto)

This beautifully illuminated document is the famous letter of introduction dated April 1588, from Dom Duarte de Menezes. Viceroy of India addressed to Toyotomi Hideyoshi who had ordered the expulsion of the Jesuits. It was presented in person by Father Alexandre Valignano of the Jesuits in Kyoto on the 3rd of March, 1591. (60.6cm x 76.5cm, Kyoto)

In order to promote trade with Japan, the Portuguese settled on the coast of China and following some ups and downs in their fortunes they found in Macau the port which they so needed to develop trade between the Middle Kingdom and the Land of the Rising Sun.

Contact with Japan which had started off in that little inlet, was to be maintained until 1639 based on two activities: one economic, the other religious.

On the economic level, the growth in trade relations promoted by the Portuguese made Macau into a flourishing, prosperous centre, forming a basis for its future as a trading city.

On the level of religion, the spread of Christianity contributed to the establishment of cultural exchange due mainly to the outstanding work of the Jesuits whose arrival in the Japanese Empire in 1549 was thanks to St. Francis Xavier.

The close link between trade and religion is explained by Father António Vieira in his História do Futuro (History of the Future: "If there were no merchants going in search of the earthly treasures to be found in the Orient and the West Indies, who would take the preachers there with their message of heavenly treasures? The preachers take the Evangelists and the merchants take the Preachers"). (7)

The pattern of trade was basically the following: from the South Seas, the ships from Macau brought the famous spices (pepper, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon) and delicacies (swallows' nests, sharks' fins, mushrooms and seaweed) which were so essential to Cantonese cuisine. In Canton, they were exchanged for high quality raw or spun silk which was then taken to Japan where it was exchanged for silver "of which there are great quantities under the soil of Japan".(8)

Luís Gonzaga Gomes says that: "the fabulous profits to be made from these transactions fully compensated for all the risks of the lengthy voyages across stormy seas plagued by daring pirates of all races. From 1550 on, trade with China and Japan became a monopoly with trading rights conceded by the king of Portugal or the viceroy of India in his name to a nobleman for services to the crown or nation. This man was given the title of Captain-major of the Voyages to China and Japan which was shortened to just Captain-major of the Voyages to Japan. He was entitled to appoint someone else to go on the actual journey. As time went by, town councils were also allowed to concede the rights to these voyages and they were sold off by auction with the profits paying to build fortresses... Later, these voyages were no longer handed out as a rewards or special favours from the King. They were auctioned and the highest bidder could either go on the voyage himself or contract somebody else to go." (9)

Seventeenth century depiction of the martyrs of Nagasaki (1597).

One of the two fathers standing in the centre of the painting is João Rodrigues. Bishop Pedro Martins looks on from the comfort of his house, similar to other pictures of the same scene. (Chrońicas de la Apostólica Provincia de San Gregorio, Fr. Juan Francisco de San Antonio, vol III, Manila, 1744)

Seventeenth century depiction of the martyrs of Nagasaki (1597).

One of the two fathers standing in the centre of the painting is João Rodrigues. Bishop Pedro Martins looks on from the comfort of his house, similar to other pictures of the same scene. (Chrońicas de la Apostólica Provincia de San Gregorio, Fr. Juan Francisco de San Antonio, vol III, Manila, 1744)

Nagasaki, Macau's "sister city", established by Portuguese traders, quickly became a flourishing sea port receiving the "Kurofuné " or "Black Ships", loaded with merchants and their merchandise. They stayed in the city, and in seven or eight months they could "spend over 200,000 or 300,000 silver coins."(10)In 1585, Father Luís Froís reported from Nagasaki that the China Ship "takes 500,000 cruzados from this port each year".

"The Christian community that the Portuguese used to have in this empire called Japan was of a great size and stretched throughout the country with many men married to Japanese women and almost naturalized, and impressive churches with ornate decorations, equally attended by a huge number of Japanese Christians from the royal family to those of most humble origins; which all came to an end for many reasons which would take too long to discuss." This is the account given by António Bocarro in his Descrição da Cidade do Nome de Deus na China (Description of the City of the Name of God in China).

Some of the "many reasons which would take too long to discuss" must be mentioned as examples of the situations and behaviour which played a decisive role in the weakening of Portuguese influence over Japan. One of them was envy of other European nations eager to replace the Portuguese in the trading which they monopolised.

The Spaniards, stationed in the Archipelago of St. Lazarus in the Philippines wanted to send mendicant friars to Japan, against the wishes of the Pope who had expressly forbidden the presence of missionary orders other than the Jesuits in the country. The Spanish then provoked incidents which were damaging to Luso-Japanese relations and gave the Portuguese a bad reputation in Japan.

As well as the English who specialised in plotting in the Shogun court, the Dutch struggled vigourously to gain control of the Portuguese routes, attacking the "Great Ships" from Macau and going so far as to attempt an invasion of the City of the Name of God. Although they failed in this last ploy, they occupied strategic posts in the Orient -the Straits of Malacca and Formosa -whence through persistent coercion they managed to strip the Portuguese enclave of its traditional routes.

After Hideyoshi's death in 1598, the Tokugawa dynasty came to power thus determining the fortunes of the Empire of the Rising Sun for two centuries. This was a long and difficult period in Japan's foreign relations due to a strong isolationist policy.

In 1614, Japanese Christians received a major setback: the missionaries' "daifusama", leyasu, published an edict ordering the expulsion of all Catholic missionaries. In 1623, another edict came out forcing all Portuguese residing in Japan to return to Macau in their galliots once the business season was over. Those men who had married were allowed to take their sons but they had to leave their wives and daughters behind.

Some years later, the peasants and crypto-Christians in Shimabara rose up in a famous rebellion against the feudal lords. The rebels carried "religious flags with mottos in Portuguese such as Praise be to the Most Holy Sacrament and shouted the names of Jesus, Maria and Saint James",(11)when they charged against the tyrants' troops.

This provided the Japanese authorities with the opportunity to accuse the Portuguese of having instigated the revolt. The popular uprising ended in 1638 with absolutely no proof of Portuguese involvement, but "lyemitsu's neurotic fear of the subversive effects of Catholic propaganda" (12)remained. The message behind this western religion became a destabilizing factor in the political, economic and financial workings of the Japanese empire. The shogunate felt threatened and, well aware that it had to get rid of it, began an anti-Christian purge which ended up being an anti-Portuguese purge.

In 1639, an imperial decree put an end to the contact initiated in 1543 in friendship by the three nambans at Nishimura Bay on Tanegashima.

"The country is in a state of confusion due to the incessant clamour of false religions.

When will the time come for making the barbarian tribes take their leave?"

(Date Masamune, 1567-1636)

Top:

The arrival of a Portuguese mission (detail from a namban-byobu).

Bottom: Famous portrait of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98), detail from a beautiful painting kept in Kyoto's Kodai Temple.

In spite of there being some controversy regarding the identity of the first Europeans to tread on the beaches of "the island of Japan" and the date on which this event took place, it seems certain that they were in fact Portuguese. During this period Europe was represented in this part of the world by Portuguese ships.

The Ryukyuans, inhabitants of the Ryukyu archipelago which is now part of Japan, were an active, seafaring people who traded Chinese goods with Japan and other ports in the Far East.

"The Malays tell the people of Malacca that there is no difference between the Portuguese and the Ryukyuans except that the Portuguese buy women and the Ryukyuans do not", Tomé Pires wrote in his Suma Oriental.

Before the Portuguese cast anchor at Malacca and explored the Malayan coast, the Ryukyuans were the ones who had control of this vast geographical area, bringing gold, copper, silks, musk, porcelain, damask, vegetables and onions to Malacca. They visited Malacca every year to trade with the Portuguese, taking back one to three junks laden with clothes from Bengal.

The Portuguese were at the height of their expansion and naturally they were looking to increase their sphere of interest, reaping back the investment they had made in ships and equipment.

Setting off from Malacca for Japan must have been considered, but it was only when the Portuguese had gained a firmer foot in India that they could carry out their plan. Trade with the Ryukyuans had pointed the Portuguese towards this destination and it was an area which they would never give up.

The establishment of trade relations was the first step in the development of more significant relations which arose from frequent contact between Portuguese and Japanese traders. Certainly, given that the Japanese were not seafarers, according to Tomé Pires' account, they handed over their trade with the outside world to those who landed on their shores. The Portuguese go-betweens, originating from another culture with different traditions and customs, brought not only trading exchange but also other exchanges of a less commercial nature. "The preachers take the Evangelists and the merchants take the preachers", but the preachers took more than the Evangelists!

A new culture expressed by art and literature had reached the Far East. Warfare and the organization of armies were also influenced by new western ideas. The political system underwent of series of alterations: the country had been split by domestic fighting but with the arrival of the musket, there came unification.

Had the Portuguese not gone to Japan, this unification would have come much later, if at all.

In closing this article on Portuguese influence in Japan from 1543 until 1639, I should like to point out that there was a resurgence in Luso-Japanese relations towards the end of the 19th century with Venceslau de Morais as its leading light.

"I arrived in Japan, I loved her in transports of delight, I drank her in as one would a nectar." The enchantment of the Orient was to mark Morais' destiny, leading him to live to the end of his days in voluntary exile in the country which he tried to understand, researching the secrets of the Japanese soul.

Through his writing, the Portuguese learned about the history, the family, "the inate refinement of the women ", the legends and gods, the art and literature, "the cherry blossom" in Spring, the tea plantations and "the green ocean of rice-paddies" of Japan, the country which Venceslau de Morais loved with the intensity and passion known to solitary souls.

Azuchi Seminary (on the west bank of Lake Biwa) founded by Alexandre Valignano in 1580 and destroyed two years later in the disturbances following the murder of Oda Nobunaga. (Compendio delle Heroiche, et Gloriose Attioni et Santa Viata di Papa Greg. XIII...., by Marc' Antonio Ciappi, Roma,1596)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Bocarro, António - Descrição do Cidade do Nome de Deus na China, in Boxer, C. R., Macau na Época da Restauração.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph - As Viagens de Japão e os seus Capitães-Mores (1550-1640) -Escola Tipográfica do Oratório de S. J. Bosco (Salesianos), Macau, 1941.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph - O Império Colonial Português (1415-1825) - Edições 70.

- Boxer, Charles Ralph - The Christian Century in Japão - 1549-1650; University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, and the Cambridge University Press, London, 1951.

- Bunchi, Nampo - Teppô-Ki (Musket Chronicle) in Tanegashima - Teatro de História Luso-Nipónica, pub. by Biblioteca do Complexo Escolar de Macau, 1988.

- Gomes, Luís Gonzaga - "Os inícios da cidade de Macau" - in Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, volume III, nos, 3 and 4, Macau, 1969.

- Janeira, A. Martins - Figuras de Silêncio-A Tradição Cultural Portuguesa no Japão de hoje -Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar, Lisboa, 1981.

- Morais, Venceslau de- A vida japonesa-Third series in Cartas do Japão(1905-1906) - Livraria Chardron de Lello e Irmão - Editores, Porto, 1985.

- Moris, Venceslau de - Relance da Alma Japonesa, 2nd edition, 1973, Parceira A. M. Pereira, Lda. Lisboa.

- Pinto, Fernão Mendes - Peregrinação-Col. Livros de Bolso, Europa-América.

- Pires, Benjamim Videira, S. J. -A Embaixada Mártir-2nd edition, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988.

Translated from the Portuguese

by Marie Imelda Macleod

NOTES

(1)Nampo Bunchi, Teppo-Ki (Musket Chronicle), p.27.

(2)idem, p. 28.

(3) idem, p. 29.

(4)Tomé Pires, Suma Oriental, pp. 373-374.

(5)Armando Martins Janeira, Figuras de Silêncio, p. 211.

(6)Fernão Mendes Pinto, Peregrinação, vol II, p.28.

(7)Quoted in C. R. Boxer, O Império Colonial Português, p. 81.

(8)António Bocarro, Descrição da Cidade do Nome de Deus na China, p. 40

(9)Luís Gonzaga Gomes, Os Inícios da Cidade de Macau, p. 271.

(10)Quoted in C. R. Boxer, O Império Colonial Português, p. 79.

(11)Benjamim Videira Pires, A Embaixada Mártir, p. 43.

(12)Quoted in Benjamim Videira Pires, A Embaixada Mártir, p. 48.

(13)Quoted in Armando Martins Janeira, Figuras de Silêncio, p. 56.

(14)Venceslau de Morais, A Vida Japonesa.

(15)idem.

(16)idem.

*History graduate (Coimbra Uni.), researcher of Portuguese History in the Orient.

start p. 91

end p.