"Mountains and lake" by Dai Jin, Ming Dynasty.

"Mountains and lake" by Dai Jin, Ming Dynasty.

In the first article I dealt with the core aesthetic concept of traditional Chinese painting. That is, I concentrated on the expression of "spirit" in harmony with "form" and the priority given to "ideas" combined with "rules". Using the previous article as a base, I shall now develop these ideas further, commencing with an examination of artistic techniques in Chinese painting.

THE BEAUTY OF INDIVIDUAL PERSPECTIVE

Perspective is the foundation stone of painting and has always been held in high regard by artists. In traditional western painting, perspective is determined from a fixed view-point implicit to which there is a specific distance and angle. The painter sees and draws an object which is within his range of vision and thus one can always distinguish a fixed view-point and a clearly defined line of vision. In traditional Chinese painting, however, the panoramic view offering different perspectives is given priority. The sayings "the form of the mountain is transformed at every step" and "the form of the mountain is observed from all sides" both indicate the importance given to observing the object from a moving perspective and to expressing the varying angles and distances within the painting. Different dimensions and angles can therefore be seen in paintings which follow these ideas. For example, when painting landscapes, Guo Xi of the Sung Dynasty described his method of observing in the following concise terms: "when one regards the object from a certain distance, it is imposing; when one regards it close up, its essence is revealed" (from his book 山水訓 Marvels of Nature). When an artist observes from a "certain distance" and also from "close up", he will gain not only a general view and perceive the imposing quality of the object, but he will also absorb its structural beauty and characteristics. As a direct result of this, traditional Chinese landscapes can be appreciated both from a distance and at close quarters. It is precisely this use of perspective which makes traditional Chinese paintings of mountains and rivers so beautiful.

The use of different perspectives reflects the fact that Chinese paintings concentrate on spiritual moods and ideas. Only by contemplating the object from all sides, from the front and the back, from the left and the right, from near and afar, and from above and below can the artist familiarize himself with the object and use his brush to paint his own subjective feelings and perceptions. Traditional Chinese painting permits the simultaneous representation of a spring orchid, a summer lotus, an autumn chrysanthemum and a winter plum blossom, or the depiction of the Yangtse River set against mountains and a plain to show objects together in an impression freed from the restrictions of time and space. In this kind of painting the artist has not only scrutinized his subject at different times and from different angles but he has also accumulated a profound memory of and feeling for that particular object. He has also grasped the spiritual characteristics of the object, flying high on the wings of his imagination.

THE BEAUTY OF 'SPIRITUAL' LINES

Lines and form are two essential contributors to the making of a painting. In western painting, form is most important because the painting depends on shading to distinguish light from dark while searching to maintain the "form" of the object and the condition of the real colour and light. Chinese painting concentrates on lines: it does not try merely to represent the form and structure of the object, it tries to express the feelings and ideas behind the form with the aid of brushstrokes.

In the 18th century, the English painter Hogarth analyzed lines as follows: a straight line reflects firmness, a horizontal line expresses openness, a curve shows softness and beauty, a wavy line gives the sensation of movement, etc.. It should be pointed out that this analysis does not adequately explain the function of lines in the expression of ideas. In fact, in China, the notion of "lines" stretches far beyond the scope of artistic technique. Lines have become an important means for communicating the feelings and aims of the total artistic idea. The mural in the temple of Zhao Jinggong, painted by Wu Taozi in the Tang Dynasty, is an example of this. The brushstrokes in this painting vary from thick to fine, rapid to lingering, surging to calm. The constant changes and clearly defined rhythm thus reflect a feeling of excitement and an extremely strong tendency towards movement. The overall effect of the mural is that of "fairies' frocks flying across the walls" (On the Pagodas of the Temples of Jingluo).

It should be pointed out that lines in traditional Chinese painting are actually form. In other words, the line is within the form and the form is within the line. The depiction of a mountain is an example: when the main line moves downward, it deposits more ink and thus the form can be perceived. It is frequently said that calligraphy and painting share the same origin. This certainly seems to be the case. The strokes of the Chinese characters - horizontal (一), vertical (丨), slanting from the left (丿), slanting from the right (乀), hooked (乛) and reversed (㼿) - represent the beauty of the lines applied in Chinese calligraphy. Because of their intense artistic value, these lines are also used when it comes to painting. Hence the movement of each brushstroke is either square or circular, head on or lateral, straight or curved, reflecting the elegance of infinite variations. The liveliness of these lines is as significant as the expression of ideas in the artistic process. Generally speaking, lines express the form and structure of an object while the quantity of ink shows the density of colour, the dark and the light, the negative and the positive space which all add up to an awareness of the size and weight of the object.

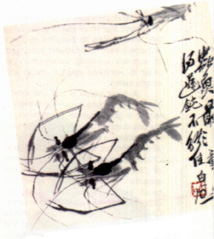

Frequently, one stroke of the brush reveals both form and line and consequently "the lines are within the form and the form is within the lines". This is why, in traditional Chinese painting, there is a combination of lines and form, and a harmony between the movement of the brush and the quantity of ink, accentuating the form, essence, movement and "spirit" of the object. The artist Qi Bai-shi succeeded in painting a transparent, live prawn with only a few brush strokes precisely because he was able to handle his brush in such a way that could produce not only thick and thin strokes, but also dark and light, and hard and soft strokes.

THE BEAUTY OF THE SHADES OF CHINESE INK

Traditional western painting emphasizes the importance of capturing the realistic colours of the objective world and the complex combination of colours which are used. Chinese painting, on the other hand, emphasizes simplicity in the use of colour and to this end Chinese ink is the main material for painting. The ink has five different hues: burnt black, dark black, deep black, pure black and light black. Artists can make use of this extensive range of blacks to portray a specific object in different layers and to show its essence, thus arriving at a classically refined style of art.

The principal use of black is in fact an important symbol of maturity in Chinese painting. In its primitive stage, artists who valued formalism "added colour according to each particular type of object". After the Tang and Sung Dynasties, the aesthetic sensibility changed from formalism to the expression of feelings, from the imitation of forms to the manifestation of ideas. This shift led to a flourishing in the art of painting with black ink. Particularly during the Ming and the Qing Dynasties, some painters preferred to use mainly black ink in their work and they completely abandoned any attempt at "imitation" of the inherent characteristics of the object. Xu Wei, an artist of the Ming Dynasty, was to write the following on one of his paintings of a peony: "The peony, the flower that symbolizes riches and a high social position, is both brilliant and splendid and is therefore usually painted in a way which accentuates these qualities. I, however, splash dark ink on paper to paint the flower for though it loses its true colours. it retains its vitality. Nevertheless, I am modest and my character is like that of the bamboo and the plumtree for I have nothing to do with riches and splendour and I believe it is good that these differences exist". His words show that he had wilfully abandoned the inherent, striking features of the peony, the "riches and splendour" by preferring to present its true nature, that of "the bamboo and the plumtree".

Attention should also be given to the most simple contrast between painting with ink and painting with colour - the contrast between black and white. Chinese painting uses black ink on white panels or materials, thus creating a very strong contrast. This is reflected in the saying "he who has not seen the mountain cannot see the plain". The shade of any colour depends on the colours which surround it and each colour differentiates itself from the others through the comparison of negative and positive space, existence and absence, light and darkness, distinctness and indistinctness, size and position in the painting. When set in contrast to each other, black becomes blacker and white becomes whiter making the main design of the painting more prominent. With the use of special materials for painting such as rice paper, the ink leaves blots which may be dry or humid, dark or clear creating variations of all kinds of tones and shades. This results in a rich and complex but nevertheless concise artistic product. "the profound expression of ideas need bear no resemblance to colour"; in fact the different shades of black ink represent a beauty which the real colours of Nature cannot attain.

THE BEAUTY OF EXAGGERATED FORM

Traditional Chinese painting pays great attention to "the expression of the spirit through form". "Form" and "spirit " are contradictory: the former is the means while the latter is the goal. Expressing the "spirit" of the object (the spiritual characteristics) in a concrete manner and the artist's spirit (thoughts and feelings) have led to a technique which emphasizes the exaggeration and deformation of natural features.

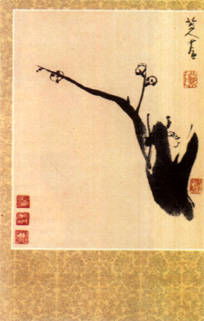

An example of this is the exaggeration of lines in drawing "women with delicate, small shoulders" or "generals with thick, short necks". These lines represent only the general outline but as far as the beauty and delicacy of the woman or the stoutness and roughness of the general are emphasized, then other details can be ignored. Likewise, colours can be exaggerated: a flower may be drawn in black, a stalk of bamboo may be painted red, a landscape may be conveyed by splashing black ink on paper. Hence we can see that the real colour of the object is ignored. The composition of the work may also be exaggerated. For instance, these Chinese sayings indicate two different kinds of painting: one that "is so compact that air cannot penetrate it"; the other "so spacious that horses can tread freely". The criterion for perfect composition consists in the complete expression of "spirit" and "ideas". Li Quingjiang, a painter in the Ming Dynasty, wrote this comment on his painting of a plumtree: "There are thousands and thousands of blossoms. While only a few deserve real appreciation". When we discard all the unnecessary ones and select only two or three and represent them in free brush strokes, then we produce a remarkable result. This is regarded as the "plumblossom method", a reflection of the style of this famous artist.

For quite a long time, imitation and exaggeration coexisted. However, as time went on, exaggeration increasingly gained importance. In order to draw freely, deformation and exaggeration gained precedence, particularly when painters began to use the "cursive hand" and "running hand" calligraphic styles and the painting method in which black ink was splashed on paper. Although there is still some imitation to be seen in the type of painting, the form and individual colours differ from the characteristics to be observed in the original object, a phenomenon which is well exemplified by the case of the "black peony". While the peony has lost its natural brightness and splendour, nobody can mistake this flower for another variety. In the drawing, the imitation serves only as a means to support the artist's own taste and purpose.

"prawns" by Qi Bai-Shi, contemporary.

"Chinese plum blossom" by Zhu Da, Qing Dynasty.

THE BEAUTY OF CONCEALMENT

From the creative point of view, overt exposition should be avoided even though it is much easier to attain than concealed expression. When an object is painted superficially on paper it is always easy to receive praise for all that it may be short-lived. Good artists, however, try all the means possible in their search to express the profound and rich essence of their subject since that is where the vitality of art lies. Ancient Chinese writings try "to express great ideas with few words", that is, to observe, to analyze and to grasp the most essential part of the subject and to express this in brief and concise language. This principle of simplification influenced the art of painting, allowing this artistic style to become succinct and concealed. Its aesthetic basis was to supress anything unnecessary in order to reinforce spiritual mood and artistic tastes.

A good article is the one which does not enunciate its opinion in explicit terms; a good musical composition is the one in which the music is suggested in the notes; a good painting is the one which hints at the idea of the work. Chinese painting renounces description of "all the details" and of "all the aspects". In other words, when the brush stroke comes to an end, the expression of the "idea" also vanishes. Chinese painting depends on the infinite expression of the "idea" beyond the brush stroke. Qi Bai-Shi once produced a famous painting called: "The croaking of frogs resounds ten "lis" (five km) from the mountain spring". Although there is no frog to be seen, there are tadpoles swimming in the spring and anyone observing the painting can feel and imagine how they will develop and metamorphose to such a degree that a vague croaking will occur "in the fragrance of the rice bloom, announcing a rich harvest". The painting of "The Great Wall" by the contemporary painter Yang Tan Wen is another example of the power of suggestion. Without going into great detail to describe the greatness and splendour of the Great Wall, the painter uses all his energy to represent its powerful, unwrought, massive base through the high, steep mountains which constitute the focus of the work. The mountains have been painted by splashing ink on paper and they are robust, vigourous, profound, spacious, misty and verdant. So many obstacles and disasters, so many difficulties and hardships, so many bloody battles, so much sorrow at parting and joy at reunion; all this goes through the mind of anyone who observes this immense landscape of mountains at the foot of the Great Wall. And yet the painting has more to offer. It seems to tell the observer: "The Great Wall is ten thousand "lis" (five thousand km) long and shall never fall" for it is built on the soil of the Chinese nation.

In a discussion of the beauty of concealed images in Chinese painting, it is also necessary to mention the question of positive and negative space. "Negative space" is the white part of the painting and "positive space" is the concrete image. In traditional Chinese painting, whatever the composition may be, the images always contain white whether they are compact or spacious. This white functions as an indication of the reciprocation between negative and positive space. White is negative space but there is positive space within it: white can represent the sky, the fields or the river; with some fish or prawns, white becomes the transparent water of a fish tank; with the outline of some birds, white turns into open countryside. The existing images represent positive space but in the positive space there is negative space. The true images contain a feeling, an idea, an interest and a style besides the atmosphere of the principal image. The water in the tank, the blue sky or the open countryside exists only insofar as there are fish swimming, birds flying or horses galloping. It can therefore be said that "fish may be painted and the water left out, yet waves can still be seen in the picture". The intimate relation between negative and positive space gives the observer a hint of an immensely rich world of imagination.

The aesthetic concepts which underlie traditional Chinese painting constitute a great source of wealth with extensive reserves the exploitation of which requires the combined efforts of many determined and energetic people. In my articles I have done no more than offer a smattering of information and comments on some aspects of traditional Chinese painting and its aesthetic foundations.

*Art Professor at the University of Beijing

start p. 51

end p.