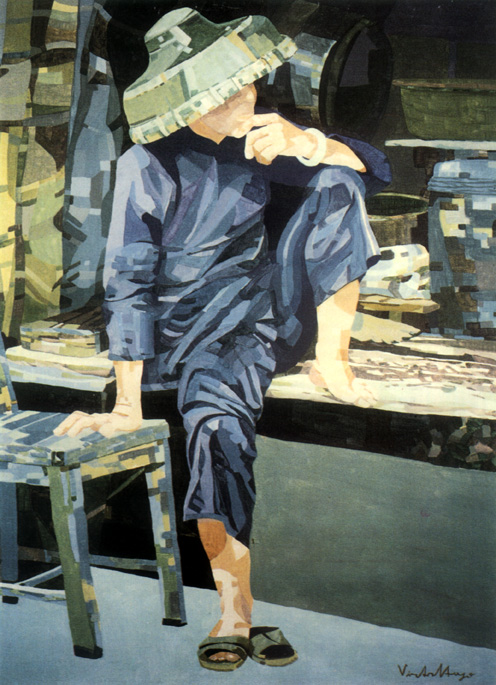

DRAWING BY VICTOR MARREIROS © COPYRIGHT 1982.

DRAWING BY VICTOR MARREIROS © COPYRIGHT 1982.

"If we wish to understand the nature of social links we should not take a series of objects and immediately attempt to establish relationships between them. Inverting the traditional approach, we should approach the relationships as terms and then the terms themselves as relationships. In other words, in the mass of social links the knots are more important than the threads even though the threads are, empirically, what cause the knots to be formed."

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Le Regard Éloigné

In a recent article on the floating population of southern China, I focussed on the opposition between this group and land dwellers and the attitude of sociological disqualification which is inherent when the latter group defines the former (cf. Brito Peixoto, 1987 a). Thus, Macau's fishing community belongs to the Tan-ka (蛋家 ) category, the Chinese word which is used to refer to the Cantonese population which lives and works in boats. This group is clearly defined by the limits imposed through endogamy. Their life-style has traditionally been the object of criticism and it is this which is supposedly responsible for the social isolation which may have prevented them becoming integrated in the Han ( 漢 ) - a status or origin which is exclusively claimed by the other Cantonese. Nevertheless, as we have seen, the cultural polarity between boat dwellers and land dwellers screens a socially complementary relationship. This condition is necessary for their intense professional specialization according to a pattern of exploitation of certain resources in the environment (cf. Brito Peixoto, 1987 b). Thus, from what we have already learned, the present image of the Tan-ka's isolation does not take into account the fact that fishing communities in southern China have lived in a symbiotic relationship with their land equivalents on whom they depend, particularly in economic matters. In fact the fisherman is linked to the U-Lan ( 魚欄 ) through a complex system of exchange. In addition to being the traditional finance agents, the U-Lan function as middlemen through whom the major part of the fishing produce is sold.

The aim of this text is to reconsider and expand these issues and then make a deeper examination of the questions which arise from them.

Ⅰ

The fisherman's survival is not guaranteed by the exploitation of maritime resources alone. He has to place his products in the market-place before he can get any return on his labour. In order to satisfy consumer demand, many of these products have to undergo various processes -salting, drying, canning, etc.. In addition to this, they have to be distributed through a complex network of local commerce and exportation. Both the processing and distribution of maritime products have inherent specific problems which need more than the skills and abilities of the fishermen to be resolved. Thus, given that the primary sector is limited to ensuring the first phase in the commercial chain for sea produce, they need intermediaries who are able to place the produce on a wider market.

Ramp for cleaning hulks, Coloane, Macau.

Ramp for cleaning hulks, Coloane, Macau.

Reciprocally, the primary sector does not only need to sell its goods but also to buy equipment and goods which again requires intermediaries in the distribution sector ranging from large importers to small retail firms.

The need for intermediaries, however, does not explain why there should be such a large number of them in practice. In Macau alone, with a fishing fleet of around eight hundred boats, there are sixty nine U-Lan firms (dealers who sell fish wholesale) (cf. Serviços de Estatística, 1987). This duplication of services is often interpreted, by the western mind, as 'irrational',economic 'laissez-faire' or by simply reacting with a shrug of the shoulders and saying that "in Macau, things are done differently". These all fail to recognize the intrinsic character of this phenomenon. Alternatively, these interpretations underestimate the fact that the intermediaries also function as credit agents. It should not be forgotten that the multiplicity of small fish dealers is situated in the context of an industry where capital is scarce and consequently where a significant proportion of commercial transactions - the sale of boats, equipment, sale and resale of products -and payment for a variety of services (including some of a social nature such as funerals and weddings) are carried on by a credit system. In the majority of the cases the creditor has limited funds which means that he can only finance a limited number of debtors. All the same, these transactions take on the form of a confidential arrangement, that is without a guarantor or banking agency. There are no other formalities other than a verbal contract between individuals who have known each other for a long time. That is why the number of debtors with whom any one creditor can have links is necessarily limited even when the latter has a large amount of money available. This is not, however, a common occurence.

Ⅱ

Fishermen in other parts of the world always return to a port where their families are established. In the South of China, where fishermen live on their boats and the crew comprises the family itself (cf. Brito Peixoto, 1987 b), the fisherman is seen as a kind of nomad with no connections to any specific place. This attitude, shared by westerners and Chinese alike, is evident in the idea that the Tan-ka are the 'gypsies of the sea', 'here today, gone tomorrow' just like 'drifting flotsam', etc.. Yet, quite the opposite from these attitudes which reflect extensive ignorance about fishing communities, it is the fisherman's life style which dictates where he lives. I shall analyze briefly some of the factors relevant to this situation.

In material terms the fisherman needs a safe and sheltered anchorage exactly like the one offered by the natural conditions in Macau's Inner Harbour. This is particularly exigent in a region which suffers from typhoons and other tropical storms which can cause severe damage to both property and people. The fisherman needs an adequate area where he can regularly clean the hull of his boat which is prone to marine deposits (cf. fig. 1). Until quite recently, they also had to find space on land to carry out work making sails, ropes and nets as well as cleaning and drying them (cf. Barbosa Carmona, 1953). With the arrival of nylon and other synthetic fibres, the fisherman now uses prefabricated materials which are technically superior even though this has led to an even greater dependence on the ship-chandlers on land. The same is true of the move from wind power to motorization. In addition to the added equipment, this requires technical assistance and fuel which leads to an even closer association with businesses on land. Obviously, not all of these requirements have to be met in the same shop although there are usually additional advantages when this is the case.

Another relatively recent factor, but one of growing importance, is the need for the children to receive an education. Many fishermen have other boats which remain anchored in the harbour. Members of the family whose failing health no longer permits them to participate in the heavy fishing tasks, but who are still able to keep an eye on the children, stay in these boats and the children can go to school. The tendency to remain stationary is sometimes reflected in the form of houses built on stilts close to the banks and, if there is enough money, in apartments in the city.

If questioned on this point a fisherman may reply that his link to any one area comes from his 'fong soi' (風水). By this he means not only an advantageous geomantic configuration of hills, water, rocks and other features of the earth (cf. Topley, 1964: p. 171) but also the beneficial influence held by the god ('san' 神) of the local temple where he worships. In Macau the A-Ma, Ma Kok Miu Temple (媽閣廟) is one of the most beautiful and most charismatic temples in the South of China (cf. Teixeira, 1979; Batalha, 1987). Fishermen never fail to observe the rituals connected to the temple and they spend large sums of money on them. Boat dwellers believe that Tin-Hua (天后), the divinity who is called 'Mother' (A-Ma 阿媽), can give them prosperity and success in their fishing, good health and numerous offspring, benefits which can bring them immediate improvements in their life style. On the other hand, the boat dwellers visit the temple regularly where they invariably meet during certain cyclical festivities whose ceremonies are considered compulsory for all.

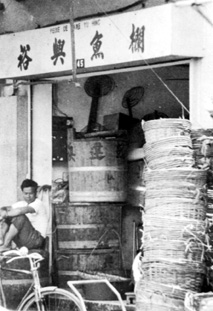

"Lane" - U-Lan (魚欄) - establishment for the wholesale of fish. Note the duplication of establishments offering the same service.

"Lane" - U-Lan (魚欄) - establishment for the wholesale of fish. Note the duplication of establishments offering the same service.

Nevertheless, the most important requirements which determine where the fishing communities establish themselves are economic and financial, a basic conditioning factor of their existence. The fisherman depends on extracting natural resources which in turn are subject to seasonal variations and unforeseeable fluctuations. In this context, the credit systems play a crucial role. Even then, however, credit is only given on the basis of personal relations cemented through a long friendship and nourished by frequent and regular contact. Thus with no fixed base the fisherman would be unable to obtain the finance which is so necessary to him. For example, there are cases of families who have moved from the People's Republic of China to Macau in order to try and enter the local market. The difficulties which they encounter go beyond the initial inconvenience of not having documents which authorize them to come to this area. The first problem is trying to find an U-Lan prepared to buy their products, not an easy task given the pressures from local fishermen. Trying to obtain credit is out of the question. Often these frustrating expeditions end up with the Chinese fishermen being forced to go to the fishermen of Macau who then act as their middlemen in unloading fish next to the local U-Lan. This process is so disadvantageous to them as to discourage any later attempts to settle in the Territory.

Ⅲ

Thus the fishermen of southern China depend not only on a market which is external to their community but also on a specialized class of financier-intermediaries, the U-Lan, who live on land and may belong to a different ethnic and linguistic group. Everything occurs as if the U-Lan, who has a certain amount of capital, were a banker and investor while the Tan-ka, who has no capital, serves as a kind of specialized manual labourer. Hence, when the fisherman requires a new boat, the most common method is for the U-Lan to advance a substantial part of the capital as a type of loan. On his side, the only guarantee from the fisherman is a kind of pawn on his catch. In other words it is not his boat which is security for the loan but rather the products which are extracted when using it and which the fisherman is obliged to sell to the U-Lan. The U-Lan regains his investment by a system of installed repayments which are made around the time of the Lunar New Year. It is interesting that when the U-Lan are questioned on this system they reply sharply that they charge no interest. This answer exasperates administrators who regard it as a method of tax evasion. The fact is that things are done differently: the 'interest' which the U-Lan charges is a reduction in the price paid for the fish. This reduction is passed on to the retailer and finally to the consumer. The comparatively indefinite nature of the amount of interest causes problems. Traditionally, the U-Lan charge a 6% commission on the selling price of the catch. Added to this is the 6% commission of the retailer which means that the fisherman should receive the value of the selling price less 12% (cf. Gonzaga Gomes, 1949; Ward, 1955). However, the U-Lan's commission is not fixed. It can vary with the amount of the loan, the intimacy of his relations with the fisherman, etc.. This gives rise to accusations of fraud, reflected by the Tan-ka saying that "there are eighteen taels in an U-Lan's khat"(1). It is difficult to find out concrete facts on this, however, as the accounts for these transactions are kept in total secrecy. Little is known about the quantity of the loans, of the fish which are unloaded and the commission rates. This information would not be easily obtained on land either.

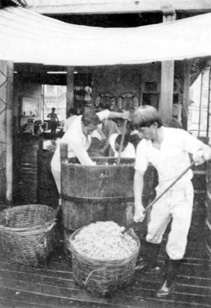

U-Lan (魚欄). Inner Harbour, Macau.

U-Lan (魚欄). Inner Harbour, Macau.

We should note that the creditor does not pressurize the debtor into repaying the whole of the debt. With the installed repayments the fisherman repays only a fraction of his debt and can be assured of credit in the future. In practice, the debtor can never repay the whole amount nor, on the other hand, does the creditor expect him to do so. It seems to be in both of their interests to allow this relation to continue whereas it would end if the debts were repaid. The Tan-ka depend on the U-Lan for finance and, in turn, the U-Lan know that they have a source of income from the Tan-ka. Neither the U-Lan expects to see the total amount of his loan back nor does the Tan-ka have any intention of fully honouring his obligations.

We have not only seen how the primary sector needs to sell its products but also how it needs to purchase equipment and materials. The U-Lan usually do not provide for the latter and to obtain these goods the Tan-ka generally maintain another kind of credit relationship. That is, the loan obtained from the U-Lan for, to take a given example, the purchase of a boat will only cover the initial costs for the shipyard services and paying for the equipment. The rest is paid for by credit and repaid in a series of installments in a similar manner to that already described. In theory, all debts should be paid around the time of the Chinese New Year. Sometimes they are. In practice, and in the majority of cases, the fisherman gets in contact with the creditors and negotiates the payment of an installment which will keep the credit agreement open until the following year. Usually the price of goods bought on credit are no higher than those paid for on the spot (cf. King, 1954) even though a percentage which can vary according to the relation between the creditor and the client is added to the total.

Ship-chandler, Inner Harbour, Macau.

The negative aspect of the opportunity to gain "credit" is, of course, the "debit" situation. The fisherman of Macau lives in a constant situation of debt to the U-Lan to whom this situation is particularly advantageous. This situation may, effectively, give way to unscrupulous exploitation (cf. Anderson, 1970; Kani, 1967). However, to highlight only this aspect of the question and the real dangers which it involves while dismissing the need for the intermediary and the importance of his financial assistance would be to assume an unrealistic stance. Thus I shall begin by outlining the reasons for the need for the intermediary which, in turn, shall make the existence of a credit system equally indispensable. The primary fishing sector would not be able to produce were it not possible for it to gain access to a market to sell its products, were it not possible for it to buy equipment and consumer goods at the same time and, naturally, were it not to have some capital. Under these circumstances this credit system functions as a lubricant which oils the production cycle. On the other hand, this in no way implies that those who provide loans or give credit to the primary sector do so with the social objective of boosting the fishing industry. Certainly these agents try to reap the greatest advantage possible and extract the greatest quantity of dividends possible in their situation as creditors. Nevertheless, it remains a fact that they carry out an essential economic role. In Macau at present there is no other body or organization which provides this service. Moreover, these economic agents are mostly small establishments many of which are themselves in a situation of debt and risk. At the end of the day they are as dependent on their debtors as the latter are on their creditors. Therefore, the security of the debtor rests precisely on the multiplicity of creditors.

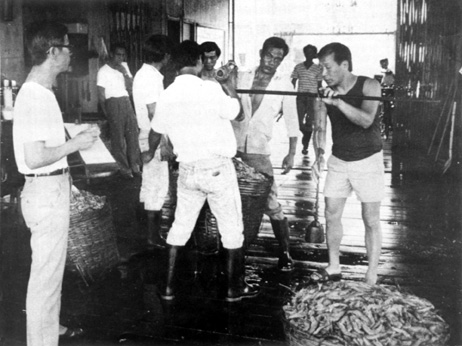

Unloading fishing, Inner Harbour, Macau

Ⅳ

The points which I have outlined should be interpreted only in the context of Macau's specific circumstances where the Portuguese administrative attitude of non-intervention in fishing allows it to continue, even nowadays, according to the traditional patterns of Chinese social organization. In the neighbouring colony of Hong Kong significant changes have been being carried out since the end of the Second World War. Following the Japanese occupation, the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries proposed setting up organizations to market the produce of the primary sector. These proposals significantly restricted the traditional power of the intermediary (cf. Topley, 1964). In the case of fishing, the government-controlled Fish Marketing Organization made wholesale selling of fish outside the official markets illegal. This was aimed at allowing the fishermen to profit from fair weights, public price quotations and an auction where the fish would be bid for in order to stimulate price competition between the intermediaries. These measures were soon followed by the implementation of fishermen's cooperatives with the assistance of the British administration to support the Fish Marketing Organization's attempts to free the fishermen from the U-Lan's loans. With this in mind, assistance funds were arranged to provide loans at a fixed rate of interest which would be openly accounted (cf. Department of Agriculture and Fisheries; Petersen, 1970).

Unloading fishing, Inner Harbour, Macau

Thus the U-Lan compete, at present, with the official loan system, having lost their monopoly on the wholesale selling of fish and at the same time having been removed from their position of control over the development of the industry. Likewise, the government of the British colony claims that without their intervention it would not have been possible to achieve the rapid mechanization of the fishing fleet. It should not be assumed that the traditional role of the U-Lan has been completely wiped out. Some of the reasons for maintaining the traditional system are: the U-Lan's loans are arranged without the bureaucracy imposed by the official system; the cooperatives impose limits on the loans for certain "social" expenses such as weddings and other ceremonies; the repayment of the official loan follows a rigid scheme even when the fisherman finds himself in dire straits (cf. Anderson, 1970).

Finally, it would be more interesting to learn about the evolutionary pattern of this economic-financial relationship in the People's Republic of China after four decades under a socialist regime which has implemented a system of communes. Unfortunately, however, there is a complete dearth of data in this area.

V

The fishing industry in the south of China has become the focus of a process of technological innovation, part of the economic boom and industrialization which has been affecting this region. For example, many junks are now equipped with sonic depth gauges, satellite navigation and other sophisticated equipment. Nevertheless, this increase in the use of technology is still developing against a background of social relationships which proceed according to patterns of traditional values.

Weighing fish, Inner Harbour, Macau

In fact, the fishermen of southern China remain a distinct ethnic category - the Tan-Ka - whose professional specialization continues to represent a fundamental element in their identity. The traditional view relegates the fisherman to the lowest position in the local social stratification. Thus his position of economic inferiority is frequently explained in terms of his alleged nomadic existence and social isolation, a result of living on his boat. This makes it difficult for him to gain an education and he is labelled with the stigma of being ignorant and superstitious. This attitude, held by the "land dwellers" but also partially held and internalized by the "boat dwellers", underestimates the fact that both groups are intimately linked to each other through a series of protracted credit agreements which can be seen as the source of the fisherman's alleged poverty and lower social status.

In short it may be said that in Macau these credit relationships have two sources: the intermediary (the wholesaler) and the supplier (retailer). In either case the type of credit system implies a limited number of debtors per creditor. This limit is defined by two factors: on the one hand, the small amount of capital available to the creditor; on the other hand, the creditor's need, in this context, to have personal knowledge of the debtor's circumstances. This explains the existence of a relatively high number of creditors, linked to a multiplicity of intermediaries and suppliers. Finally, this kind of market is regulated neither by government policy nor by free competition but rather by interpersonal relationships which depend on the fishing economy without which production would not be feasible. This extremely localized system is, in turn, one of the factors which most determine the stability of the fishing communities, contrary to the gross caricatures which show them as wandering nomads.

It is difficult, at first, to imagine how the tiny Territory of Macau, where the Portuguese have been established for centuries, with its staggering economic growth, could be a centre of Chinese tradition (cf. Brito Peixoto, 1987 a). But the fact remains that as far as the fishing industry is concerned, Macau is one of the few places where it is still possible to see the social organization of the fishermen from southern China in their traditional mould. The main reason for this phenomenon comes from the fact that these patterns have been destroyed in China due to their incompatibility with the principles of a Marxist state. Consequently, Macau, the crossroads between the traditional and the modern, is unique in its own geographical location between the People's Republic of China and Hong Kong. Without being aware of it, the observer is taken on a journey through time and is given an image of a world which has already disappeared in China but which is waiting for another world, that of Hong Kong, to reach its shores.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Eugene N.

1970 The Floatying World of Castle Peak Bay. Washington D. C.: American Anthropological Association.

Batalha, Graciete Nogueira

1987 "This Name of Macau", Review of Culture N° 1, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 7-14.

Barbosa Carmona, Artur L.

1953 Lorchas, Juncos e Outros Barcos do Sul da China. Macau: Imprensa Oficial.

Brito Peixoto, Rui

1987(a) "Boat People, Land People", Review of Culture N° 2, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 9-20.

1987(b) "Habitat, Technology and Society", Review of Culture N° 3, ed. Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 8 - 20.

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Gov. of Hong Kong

1966-1986 Annual Report. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

1966 Statement of Fisheries Development Loan Fund.

1968 General Statement of Aims for the Development of the Fishing Industry in Hong Kong.

1976"A General Review of Fishermen's Co-operatives in Hong Kong". Fisheries Occasional Paper N° 10.

Gonzaga Gomes, Luís

1949 "A Pesca na China e em Macau". Revista Macau, pp 26--35.

Kani, Hiroaki

1967 A General Survey of the Boat People in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: New Asia Research Institute.

King, Frank H. H.

1954 "Pricing Policy in a Chinese Fishing Village". Journal of Oriental Studies, vol. 1, N° 1, pp 215-226.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude

1983 Le Regard Éloigné. Paris.

Petersen, I.

1970 "A brief account of the administration of the fishing industry in Hong Kong". Hong Kong Fisheries Bulletin, N° 1, pp 1-4.

Serviços de Estatística e Censos, Governo de Macau

1987 Inquérito às Embarcações de Pesca.

Teixeira, Manuel

1979 O Templo Chinês da Barra. Macau: Edição do Centro de Informação e Turismo.

Topley, Marjorie

1964 "Capital, Saving and Credit among Indigenous Rice Farmers and Immigrant Vegetable Farmers in Hong Kong's New Territories" In: R. Firth and B. S. Yamey, eds., Capital, Saving and Credit in Peasant Societies. Chicago: Aldine.

Ward, Barbara

1955 "A Hong Kong Fishing Village". Journal of Oriental Studies N° 1, pp 195-214.

1967 "Chinese Fishermen in Hong Kong: Their Post-Peasant Economy". In: Maurice Freedman, ed., Social Organization: Essays Presented to Raymond Firth. Chicago: Aldine, pp 271-288.

NOTE

(1) Khat: a Chinese measurement of weight (Kan 斤), equivalent to 610 grams. There are sixteen taels in one khat.

* Diploma in Clinical Psychology (ISPA), Graduate in Ethnological and Anthropological Sciences (ASCSP). Masters in Social Anthropology (King's College Cambridge). ICM Scholarship holder.

The present article was produced in accordance with conditions stipulated by the ICM and represents the initial stage of a research project on Social and Cultural Anthropology in Macau's fishing community. The brief time in which it was written constituted no more than a pause for reflection during the work at present being undertaken. At the moment I have limited myself to giving an outline of the issues, providing provisional observations. To this end I have written for an informed public although not necessarily specialized in Anthropology or familiar with this particular ethnological field.

start p. 7

end p.