"He was exceptionally talented

in handling business,

unusually virtuous and prudent,

humble, zealous, poor and obedient,

but of impatient character and austere nature."

From the middle of the XVIth Century the Portuguese wrote so prolifically on History that after studying the diverse bibliography on this area it is difficult not to notice the lack of material on Music. Music is our companion in both our sad and joyful moments. For this reason an examination of the musical history of the Portuguese in the Orient should be given priority and the names found of those great men who are now forgotten but who, in their time, helped to spread the fame of Portugal.

The musical history of this distant corner was developed by remarkable characters. They are not known in their own country yet the Portuguese cultural heritage is indebted to them.

The Portuguese who arrived in the East were, on the whole, energetic and honourable men. They brought with them a clearly defined image of what was Portuguese culture. In audiences with the Emperors, with the highest dignitaries of these vast kingdoms or in conversation with the Scholars, numerous Portuguese displayed a lively intelligence and exceptional abilities, expending their energies until the end of their lives.

The Portuguese were dispersed throughout distant parts of the East. It was in Macau, however, the peninsula which sits at the very south of Guangdong Province, the gateway to the Celestial Empire, that the Jesuit Fathers established their base in the famous Colégio de S. Paulo. This was to be a remarkable cultural centre where Literature, Sciences and Arts would make an outstanding contribution to the East.

The Jesuits introduced western Mathematics to China. They also established the Astronomic Observatory in Beijing (at that time known as Pei Ping) and introduced western style Diplomacy and Arts. United in their missionary fervour and the desire to spread the Christian faith, they became genuine disseminators of modern civilization in the Far East.

Over three centuries ago, Father Tomás Pereira was one of those who passed through this tiny, charming spot where the turbulent waters of the Pearl River and the West River lap against the shores.

"Descended from a noble family named Costa Pereira, the son of Domingos Costa Pereira and Dona Francisca Antónia da Costa Pereira, born in S. Martinho do Vale in the district of Barcelos and the archdiocese of Braga"(1) on "the first day of November, 1645."(2)

When he entered the Company of Jesus on the 25th of September, 1663(3), at the age of eighteen, he gave up his baptismal name, Sancho, for that of Tomás(4).

Three years later, on the 15th of April, 1666, he left for India at the tender age of twenty one. "It is not known whether he finished his Degree and became a Master of Arts there or in Macau where he arrived in 1672".(5)

There is still a great deal of uncertainty about the six years which Pereira spent in India from his departure to the East in 1666 until 1672 and little light is thrown upon the subject from existing documents.

However it may have been, Tomás Pereira was already in Macau in 1672 when the Emperor K'ang-Hsi of the Ching Dynasty called him to an audience at the court after hearing him praised boundlessly by the Belgian astronomer Verbiest. The following text confirms this: "after hearing of his great talents and moral qualities, of his learning and in particular of his un usual expertise and dexterity with music and machinery"(6), the Emperor sent a small embassy led by two mandarins to escort Tomás Pereira from Macau to Beijing. "The mandarins were received with all the honour which was due to the prince whom they represented. They carried out their mission and the visiting Father Valgariano commanded Father Tomás Pereira to go with them. They reached Beijing in January of 1673 after receiving displays of deep respect from all the mayors of the cities through which they passed. As soon as the audience began, the young Father was so well received by the prince that they established a friendship which was to last for thirty six years".(7)

It is a well known fact that Music was one of the principal means of evangelization in China. How could it have been otherwise when Music has always held the greatest fascination for men throughout the ages? In fact, Music is as expressive and communicative as any other art. The difference is that it also exercises a series of powerful mechanisms which cannot be rationally explained.

In view of the fact that Music was one of Father Tomás Pereira's special talents, it is natural to ask how much training he had in this field.

What did he learn in Braga up to the age of eighteen? Or in Coimbra during his novitiate from eighteen to twenty one? And in the East where he gained a degree and was exposed to a different musical register from that of Europe?

Renaissance Europe had developed vocal polyphonics to the peak of perfection. Following that, the Baroque period marked a great turning point for men and arts striving for ever greater achievements and finding new musical forms such as operas, oratorios, cantatas and concertos. This indicated a major development and instruments which had, until then, been subjugated by the voice, were brought into their own.

During his twenty one years in a declining Portugal, which aspects of this evolution would have been known to Tomás Pereira, the musician?

What is more, how and where can he have acquired the knowledge to build organs? To do this you need not only mathematical skills (which he had) but also a knowledge of acoustics, engineering and other areas. There are numerous questions which have to be asked about the varied career of this illustrious but little known Portuguese man.

In one of his letters dated the 30th of August, 1681, he refers to his activities as an organbuilder. His humility is evident from the text as he writes behind the cover of the third person:

"For this reason the same Father built an additional organ which has four different stops... the longest pipe is over two ells long. It was installed in the Church this year. Such were the crowds and the applause that we were obliged to mount a guard at the doors of the Church and in the grounds to prevent the heathens from creating a disturbance and to control the crowds who came to see it. They had never seen anything like it in their lives so the author was obliged to play for many hours each day for more than a whole month. Sometimes he played for no more than a quarter of an hour each time, letting in a new group of people at each quarter hour so that all could hear. The instrument caused a great commotion in the people of these parts. The spirit of the music entered the souls of the more sensitive and many of them have decided consequently to follow the faith, this being our most cherished aim".(8).

The length of the longest pipe was two ells (over 2.20m). This pipe produced the lowest sound on the instrument but its exact pitch cannot be deduced from this information alone. We would also need to know the inside diameter of the pipe, the height and width of the mouth of the pipe and the thickness and width of the opening at the foot of the pipe.

Whether he played sacred Portuguese music, music which he improvised on the spot or Chinese melodies is something which Father Tomás Pereira refrains from telling us. However it may be, music was played and it is interesting to note the Father's hope that through listening to the music the people would turn to the faith. This confirms my earlier comment about the importance of music in missionary work in China. The final objective of the missionaries, to be officially allowed to worship God freely in China, was to be delayed for a further eleven years. When it happened, however, it was a crowning glory for Father Tomás Pereira.

In a second letter, sent from Beijing on the 10th of June, 1682, Father Tomás Pereira writes to the Portuguese envoy in Rome about "some organs which I have made for the Emperor". He also says "I am well aware that on first impressions the Portuguese will be very surprised to see me amongst all this tubing, but I believe that the Lord can be praised through music and my only wish is to accomplish my mission on Earth and be rewarded in Heaven."(9)

This passage reflects Father Tomás Pereira's missionary fervour as well as his most cherished ideal which was to expand the Christian Church in the Orient.

There is yet a third letter, written on the 1st of August, about one of the organs which had given particular pleasure to the Emperor. Father Tomás Pereira describes it in the following manner:

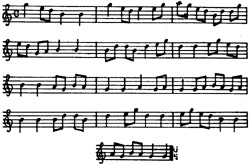

Chinese Air

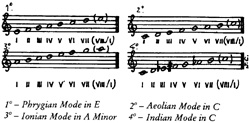

Examples of European heptatonic scales

Examples of European heptatonic scales

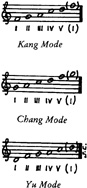

Examples of Chinese pentatonic scales

Examples of Chinese pentatonic scales

"Work has also begun on new organs. The Emperor already has many but has requested me to make new inventions. One of the organs is five yards high and it plays Chinese music on its own with no one to touch the keys. It also has a mechanism with little bells which are finely tuned to play the same notes at the same time as the organ. This has been a great success. This invention was used in the public performances of comic plays. The Emperor was present for ten days and took great pleasure in his people and the peace in his kingdom.

"Work has also begun on new organs. The Emperor already has many but has requested me to make new inventions. One of the organs is five yards high and it plays Chinese music on its own with no one to touch the keys. It also has a mechanism with little bells which are finely tuned to play the same notes at the same time as the organ. This has been a great success. This invention was used in the public performances of comic plays. The Emperor was present for ten days and took great pleasure in his people and the peace in his kingdom.

-from Description Géographique, Historique, Cronologique, Politique et Physique de l)

The organ playing by itself delighted everyone and compliments were showered upon it but it is not my place to repeat all that was said..."(10)

Thus we learn that Father Tomás Pereira had already built several organs for the court in Beijing and that Emperor K'ang-Hsi was an enthusiastic collector of "new inventions". This organ had a complex mechanical function which testifies to Father Tomás Pereira's skill in organ building.

The addition of the little bells which played out the Chinese dance tunes brings up the question of another problem, that of tuning. The notes in the scales of the Celestial Empire are different from those in European scales. One hypothesis is that the bells which were used may have been tuned to the Chinese scale, especially as there was no need to obtain the sounds of the western scales. Thus, instead of using a European heptatonic scale, Father Tomás Pereira probably opted for any of the Chinese pentatonic scales (cf. the examples of scales and the Chinese Air). The set of bells enriched the instrument's tone and sonority. This all reflects the exceptional capacity for observation and engineering skills of which Verbiest had spoken to the Emperor while Father Tom ás Pereira was still in Macau.

There is a ten year interval between Tom ás Pereira's arrival in Beijing in 1673 and the last letter which was mentioned in 1683. During these ten years one could expect an ever-increasing knowledge of the sounds which surrounded him in China. How did he interpret this music?

The remarkable Description Géographique, Historique, Cronologique, Politique et Physique de l'Empire de la Tartarie Chinoise published by Du Halde in 1735 presents us with an outline of the music of this period:

"To hear them it would appear that they invented music and they boast that they brought it to perfection in distant times. If this is true, there can be no doubt that it has degenerated since then. Now it is so flawed that it can hardly be called music as can be judged from some of the melodies which I have had transcribed so as to give the reader an idea. (cf. opposite page for one of the Chinese Airs in this Work.)

It is true that at first it was held in high esteem and the learned Confucius attempted to introduce all of his precepts in to all of the provinces where the government was sympathetic. The Chinese now deplore the fact that the ancient books of music should have been lost so unfortunately.

As for what remains, music is now used only for comic plays, in certain festivities, in weddings and other suchlike occasions. The Buddhist priests use it in their rituals but when they sing they never raise nor lower their voices the interval of a semitone but only in thirds, fifths or octaves. This harmony delights the Chinese. They all sing the same melodies just as in the rest of Asia.

They do not dislike European music when they hear the voice accompanied by some instruments. However, the most wonderful aspect of this music is in the contrast of the voices, the difference in tone, fugues and syncopation, something which seems to be completely alien to them, an unpleasant confusion of sounds.

They possess no kind of musical notation like ours, nor any marking to divide the diversity of sounds, crescendos and diminuendos and all the combinations which form our harmonies. The melodies which they sing or play on their instruments are learned by ear. From time to time they make up something new and it is Emperor K'ang-Hsi himself who composes it. When they are well played on the instruments or sung with a good voice these tunes have some appeal even to the European listener. "(11)

This is an important document describing the music of China at the time when Tomás Pereira was there, even though it lacks precision and depth of musical knowledge because Du Halde was not, as far as we know, a musician in the accepted sense of the word. If he had been, he would not have asked someone to transcribe the Chinese airs which he refers to on page 267 of his book.

This text refers to the Emperor as composer, a detail which can be connected with another text which makes extensive reference to Father Tomás Pereira. This is Suárez's La Libertad de la Ley de Dios en el Imperio de la China (Freedom of Religion in the Chinese Empire).

We know that the Emperor of the Celestial Empire was an intelligent, liberal and cultured man. He was always very open-minded towards the Europeans in his service and what little time he had left from the affairs of state he dedicated to studying Mathematical Sciences and Music.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Facsimile, ob. cit., J. Du Halde.

Suárez's book is contemporary with Father Tomás Pereira's stay in Beijing. I would like to offer the following extract from it:

"He ordered Father François Gerbillon and Father Jean Bouvet to study Mandarin with the Chinese who lived in the Palace. After learning it, he ordered them to translate the Philosophies and Euclid's Principles which they did under the supervision of Father António Tomás (not to be confused with our musician from Barcelos). Once the translations were completed, he frequently called upon them to explain what they had translated. The same Father António Tomás also took him Algebraic propositions. In spite of being difficult, the Emperor had sufficient intellectual capacity to fathom them and he took great pleasure in working on them. In addition to Music which he was already learning from him, the Emperor kept Father Tomás Pereira busy in various curious tasks..."(12)

On examining both Du Halde's and Suárez's texts it is reasonable to suppose that the Emperor's compositions referred to in the former were related to Father Tomás Pereira's teachings referred to in the latter.

Later in Du Halde's book we find other, equally important, proof:

"The ease with which we can transcribe any tune the first time we hear it took Emperor K'ang-Hsi completely by surprise. In 1679, he called Father Grimaldi and Father Pereira to the Palace to play the organ and harpsichord which they had previously given him. He savoured the European tunes and exhibited delight on hearing them. Afterwards, he ordered his musicians to play a Chinese melody on one of their instruments and he himself played very gracefully.

Father Tomás Pereira picked up his quill and wrote the entire melody while the musicians were singing. When they had finished the Father repeated it note for note without a single mistake as if he had practised it for a long time. The Emperor's astonishment was written all over his face. His praise for the rigour, beauty and simplicity of European music knew no bounds. Above all, he was amazed that the Father could have learned, in such a short time, a melody which for him and his musicians had been so difficult and that by using a few symbols the melody had become so ingrained as to be unforgettable.

In order to believe what he was witnessing he did some more tests. He sang several different tunes which the Father wrote down and then repeated immediately after without making any mistakes. 'I have to admit,' cried the Emperor, 'that European music has no equal and that there is no one comparable to this Father in all my Empire.' He led Father Tomás Pereira to his seat and presented the Fathers with twenty four bales of damask silk saying pleasantly that their robes were entirely worthless and that the cloth would enable them to make new robes."(13)

"This Prince immediately set up a Music Academy where he commanded all those who showed musical talent to study. Among them was his third son who was a scholarly man who read widely. He began by examining all the authors who had written on this subject and ordered replicas of the ancient instruments to be made in accordance with the specified measurements. There were some defects in these instruments which were corrected according to later rules. Then the Emperor commanded that a four-volume book should be written titled The True Doctrine of Music. A fifth volume, written by Father Tomás Pereira, was added dealing with European music."(14)

We have discussed the talents of the Father in his capacity as organ-builder, organist, harpsichordist, teacher and author of the above-mentioned document. Now we shall turn to his abilities as a mathematician, diplomat and missionary: aspects which complement his varied personality.

It was not only his musical gifts which made Father Tomás Pereira stand out and brought him into favour with the Emperor, a man who "took pride in believing that no one could penetrate his thoughts or guess his plans, not even his courtiers could fathom him. Father Tomás Pereira's influence was so great that one day the Emperor declared that the priest could see right through to his bones".(15)

On the death of Father Verbiest, President of the Mathematical Tribunal, the Emperor invited Father Tomás Pereira to take up the position. "The Father excused himself from the post and, along with Father António Tomás, a distinguished Belgian mathematician, he proposed that the exceptional astronomer, Father Philippe Grimaldi, should be President. The Emperor was surprised at the excuse but he accepted the proposal and ordered that in the meantime Father Tomás Pereira should be the interim President assisted by Father António Tomás. This was how the two Jesuits held the office of President from 1688 until 1694 when Philippe Grimaldi returned to Beijing."(16)

Another of Father Tomás Pereira's skills was in the diplomatic field.

Diplomacy had been the subject of his doctoral thesis. The famous Sino-Russian Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed on the 7th of September, 1689, in the twenty eighth year of Emperor K'ang-Hsi's reign. The city of Beijing shall always be indebted to Father Tomás Pereira for the principal role he played in this agreement. It is particularly important to remember that this was the first diplomatic agreement between Asia and Europe. It is worth pausing to look at some passages from Suárez's book. The first deals with the first ambassadorial expedition which was made in 1688.

"The Emperor appointed other important mandarins to accompany the two ambassadors Tumquekam and Samgotu. He also wanted Father Tomás Pereira to go with them as he had much experience in these matters... And later the Emperor rewarded another service which the Father had done by increasing his status in the mandarinate, making him a mandarin of the third degree...

The Emperor made many other displays of honour to the Father before his departure, including a gift of one of his own valuable fur coats.

At last the Ambassadors and Fathers left with an able body of soldiers. In total, there were around six thousand men. When they were not far from the town of Selenga where they were due to hold the meetings with the Muscovites, they were forced to return to Beijing. The only result of this journey was the loss of many men, horses and camels from starvation and dehydration in the desert they had passed through. Those who survived seemed more dead than alive... and the Fathers had almost died from tuberculosis."

The second expedition took place in the following year, 1689.

"This second journey was somewhat easier... there was more water in the desert... but crossing the rivers was more risky... we lost many men from drowning... and some sank in the muds. Three times the Peace Treaty had completely failed... because of crass mistakes... without taking the advice... of Father Tomás Pereira.

Father Tomás Pereira realized that he could not possibly approve of these discourtesies... and he set to work to ameliorate the situation, advising our Ambassadors and persuading them to do what was best... until they resolved to do everything which Father Tomás Pereira thought fit.

When this great Sino-Russian Treaty had been signed, they sent the two Ambassadors to take the joyful news to the Emperor. After instructing them on what they had to say, they ended with these formal words: 'Tell the Emperor that the good fortune in the happy outcome of these negotiations is thanks to him; that His Majesty has excellent judgement in men for he chose Father Tomás Pereira to accompany the expedition; that the negotiations had stalled several times but he assured its successful outcome; and that truly had it not been for Father Tomás Pereira there would have been no outcome at all. Tell him these very words and do not forget or alter anything.'"(17)

However, the crowning point of Pereira's career probably came on the 22nd of March, 1692, when the decree permitting freedom to practise the Christian faith in China was published. This wish had determined his path during the twenty one years he had spent in the Orient. He had left everything, his homeland, his family, friends, absolutely everything in order to go to Beijing from whence he would never return.

"When the wish for which they had been hoping so long and so fervently was granted, they went to the Palace to offer their thanks to K'ang-Hsi. Father Tomás Pereira delivered the following words in a speech on behalf of them all: "This joyful moment has been our sole desire, the only hope which has enabled us to endure and the only objective of which we have thought, day and night. By the grace of Your Majesty we are now permitted to preach publicly the word of the true God throughout this vast empire. As Your Majesty knows, this was the reason for leaving our families and our homelands and undergoing many dangers to come to offer you our services. You have already bestowed countless favours upon us but what you have granted today is the greatest of them all." (18)

In reports sent from Beijing to Rome in 1700 and 1703, Father Tomás Pereira is described in the following terms: "He was exceptionally talented in handling business, unusually virtuous and prudent, humble, zealous, poor and obedient, but of impatient character and austere nature".(19)

Towards the end of his life, Father Tomás Pereira was tormented by the controversial question of ritual which created the rift between the papacy and the Jesuits: "Pope Clemente XI, who had already rejected the Jesuit interpretation which attempted to adapt the Chinese religious mentality to the doctrine of Christian revelation by using Confucian precepts"(20), sent Cardinal Tournon to the Orient. The papal envoy had such a prejudicial effect that he fell out of favour with Emperor K'ang-Hsi. This put the immense amount of missionary work which had been carried out by, among others, Father Tomás Pereira at risk. The end result was that he was denied both "active and passive voice"(21).Either because of this (as was the opinion of the Emperor) or for other reasons, Father Tomás Pereira could not recover from a second apoplectic fit and he died at the age of sixty three on Christmas Eve, 1708.

The death of Father Xu Risheng, as he was known throughout the empire, caused widespread grief and the Emperor himself paid him the final honour of erecting a splendid tomb for which he wrote the epitaph(22).

Apart from the Chinese hymns which he wrote (23), Father Tomás Pereira left the following works (24):

The True Doctrine of Music, five volumes, Beijing, 1713. The first four volumes were written by Chinese authors and the fifth was the work of Father Tomás Pereira and the Italian Father Petrini. It is a treaty on European music with examples of musical notation.

Tratado de Música Prática e Especulativa (Treaty on Practical and Theoretical Music) which the Emperor ordered to be translated into Mandarin.

I hope that, in spite of whatever may be lacking from this study, I have at least shed some light upon the life and works of one of the major missionary figures in China.

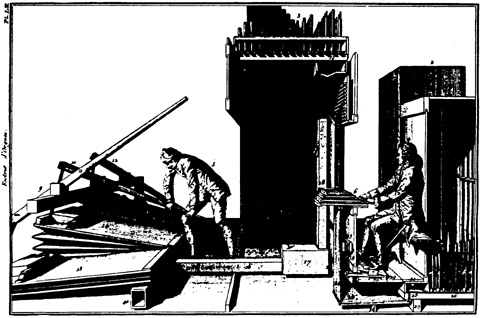

Design of a French organ of the XVIIIth Century by D. Bédos de Celles (L'Art de Facteur d'Orgues, Paris, 1766, pl. LII).

I shall close this article with some lines from the Chinese poet Uang:

Here on Earth man flickers out like the light,

Which in a moment at dawn,

Is thrown from behind the mountain.

Life is like an oil-lamp:

When there is no oil,

It goes out in an instant. (25)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

(1) Rego, José de Carvalho: "Um dos maiores missionários da China", "Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau", 62, 1964, p.999.

(2) Pfister, Louis: Notices Biographiques et Bibliographiques sur les Jésuites de l'Ancienne Mission de Chine, 1552-1773, 1932-1934, p. 381.

(3) Franco, António: Ano Santo da Companhia de Jesus em Portugal, 1st ed., Porto, A. I., 1931, p. 765.

(4) Pfister, Louis: op. cit., p. 382.

(5) Rego, José de Carvalho e: op. cit., ibidem.

Note: Father José Vaz de Carvalho kindly sent me some information to help me with my study on Father Tomás Pereira. In his letter of 15/4/87 he wrote that "he embarked for the Orient... having spent only a short time in Goa, he went on to Macau where he finished his Humanities Degree and studied Theology. He received his Masters Degree and taught Humanities for two years". I offer my grateful thanks for this information.

(6) Rodrigues, Francisco: Jesuítas Portugueses Astrónomos na China, Porto, 1925, p. 16.

(7) Pfister, Louis: ob. cit., p. 142.

(8) Rodrigues, Francisco: A Formação Intelectual do Jesuíta, Porto, 1917, p. 495.

(9) Rodrigues, Francisco: ob. cit., p. 493.

(10) Rodrigues, Francisco: ob. cit., p. 494.

(11) Halde, J. Du: Description Géographique, Historique, Cronologique, Politique et Physique de l'Empire de la Tartarie Chinoise, ed. P. G. Le Mercier (Printer and Bookshop), 1735, vol. III, pp. 265-266.

(12) Suárez, José: La Libertad de la Ley de Dios en el Imperio de la China, Lisbon, Miguel Deslandes, 1696, Part II, pp. 70-71.

(13) Halde, J. Du: op. cit..

(14) Pfister, Louis: op. cit..

(15) Franco, António: op. cit., p. 757.

(16) Rodrigues, Francisco: op. cit., p. 19.

(17) Suárez, José: op. cit., p.60 on.

(18) Rodrigues, Francisco: op. cit., p. 18.

(19) Rodrigues, Francisco: ibidem, p. 16.

(20) Azevedo, Rafael Ávila de: Influência da Cultura Portuguesa em Macau, Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa, Ministry of Education, Lisbon, 1984, p. 16.

(21) Biker: Colecção de Tratados... da Ásia..., Relação... do que Fez... na Missão da China... Tournon, vol V, p. 44.

(22) Rego, José de Carvalho e: op. cit., p. 758.

(23) Rego, José de Carvalho e: ibidem.

(24) Pfister, Louis: op. cit., pp. 384- 385.

(25) Halde, J. Du: op. cit..

* Musicologist; Artistic Director of the Academic Choral Society of Coimbra (formerly the "Orpheanists").

start p. 21

end p.