The prosperity of Macao and its dominion by the Portuguese did not please the Chinese who, in 1573, constructed the gates called Border Gate (Guang.: Kuan-Chap), a veritable frontier at which the mandarins collected taxes on goods transiting between Macao and Hongshan.

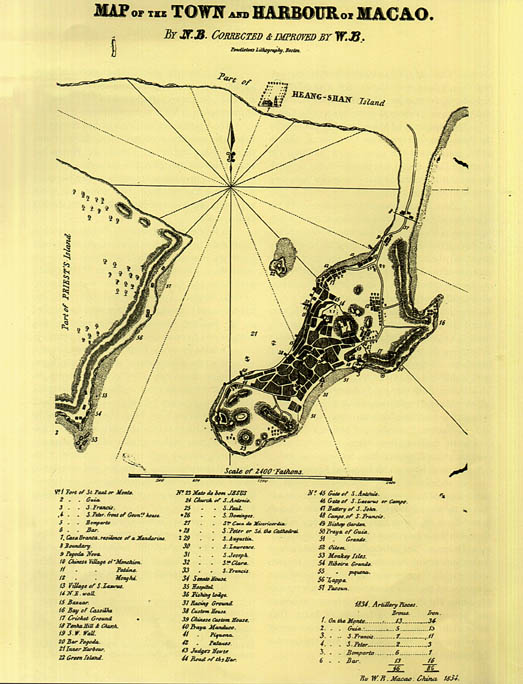

At first, the gate operated only once a week but later opened every morning and closed every night. Macao was supplied by a fair which was initially held every five days. Later it was held every fifteen days and the trading areas corresponded to the accesses of Border Gate, that is the Istmo de Ferreira do Amaral (Ferreira do Amaral Isthmus) and Rua do Hipódromo (Hippodrome Street) [W. B. - 37. Racing Ground. ]. After the construction of Border Gate Portuguese sovereignty was limited and defined. The [local] mandarin imposed certain rules controlling the population, trade, construction and buildings, and the number of ships anchored in the port, and levied custom duties.

It was however, the Portuguese community which orientated trade. It was a trade they had learned to control - profitable but improvised. And, contrary to Goa, Cochin, Colombo and Malacca that were enriched by the Portuguese, Macao was a Portuguese creation which flourished from nothing, becoming a rich emporium between Malacca and Japan.

In addition to being an important centre of merchants and navigators its most important role was played by the missionaries. The Catholic Church gave Macao an appearance which is today still reflected in the organisation of the area. Various religious Orders were established which left the mark on the settlement with the construction of their churches and convents. It was around these that the population congregated, the Jesuits attracting the greater number of people. The Portuguese lived in luxurious houses and were related to best families of India. They accumulated large fortunes thanks to the commerce with Japan and Manila, benefiting from the fact that the Spanish had ceased direct trade.

The prosperity attracted the interest of other nations who attacked the city in 1604, 1607, 1622 and 1627. Successive attacks made the organisation of an efficient defence system imperative.

The Chinese authorities who had always resisted the installation of large scale fortifications finally ceded and in 1622 made the Portuguese responsible for the defence of the area.

To improve the rudimentary sixteenth century equipment, the old forts were renovated at the beginning of the seventeenth century, after the first Dutch attack.

In spite of prosperous trade the city developed uncertainty as it swelled or emptied according to the obstacles imposed by the Portuguese or by the mandarins. Considered a fortress in 1619, it had a population two years later of about seven-hundred to eight hundred Portuguese and half-castes and ten-thousand Chinese. The latter were established on the outskirts, expanding the already existing villages and forming new Chinese settlements.

Outside the walls there were seven Chinese villages on the extremities of the peninsula (Barra and Macao Seac), and five located between the walls and Mong-há (Patane, Sam Kiu, Mong-há, São Lázaro (St. Lazarus) [W. B. - 13 Village of S. Lazarus.] and Lon-Tin-Ching. They maintained the traditional structure, the regularity of lines of modest rectangular houses, a roof and two slopes, a uniformity broken only by the adaptation of the physical characteristics of the site and the relation of the houses to the surrounding scenery (water/ fishermen, cultivated land/farmers) or an important building.

The prosperity of Macao and its dominion by the Portuguese did not please the Chinese who, in 1573, constructed the gates called Border Gate (Guang.: Kuan-Chap), a veritable frontier at which the mandarins collected taxes on goods transiting between Macao and Hongshan.

At first, the gate operated only once a week but later opened every morning and closed every night. Macao was supplied by a fair which was initially held every five days. Later it was held every fifteen days and the trading areas corresponded to the accesses of Border Gate, that is the Istmo de Ferreira do Amaral (Ferreira do Amaral Isthmus) and Rua do Hipódromo (Hippodrome Street) [W. B. - 37. Racing Ground. ]. After the construction of Border Gate Portuguese sovereignty was limited and defined. The [local] mandarin imposed certain rules controlling the population, trade, construction and buildings, and the number of ships anchored in the port, and levied custom duties.

It was however, the Portuguese community which orientated trade. It was a trade they had learned to control - profitable but improvised. And, contrary to Goa, Cochin, Colombo and Malacca that were enriched by the Portuguese, Macao was a Portuguese creation which flourished from nothing, becoming a rich emporium between Malacca and Japan.

In addition to being an important centre of merchants and navigators its most important role was played by the missionaries. The Catholic Church gave Macao an appearance which is today still reflected in the organisation of the area. Various religious Orders were established which left the mark on the settlement with the construction of their churches and convents. It was around these that the population congregated, the Jesuits attracting the greater number of people. The Portuguese lived in luxurious houses and were related to best families of India. They accumulated large fortunes thanks to the commerce with Japan and Manila, benefiting from the fact that the Spanish had ceased direct trade.

The prosperity attracted the interest of other nations who attacked the city in 1604, 1607, 1622 and 1627. Successive attacks made the organisation of an efficient defence system imperative.

The Chinese authorities who had always resisted the installation of large scale fortifications finally ceded and in 1622 made the Portuguese responsible for the defence of the area.

To improve the rudimentary sixteenth century equipment, the old forts were renovated at the beginning of the seventeenth century, after the first Dutch attack.

In spite of prosperous trade the city developed uncertainty as it swelled or emptied according to the obstacles imposed by the Portuguese or by the mandarins. Considered a fortress in 1619, it had a population two years later of about seven-hundred to eight hundred Portuguese and half-castes and ten-thousand Chinese. The latter were established on the outskirts, expanding the already existing villages and forming new Chinese settlements.

Outside the walls there were seven Chinese villages on the extremities of the peninsula (Barra and Macao Seac), and five located between the walls and Mong-há (Patane, Sam Kiu, Mong-há, São Lázaro (St. Lazarus) [W. B. - 13 Village of S. Lazarus.] and Lon-Tin-Ching. They maintained the traditional structure, the regularity of lines of modest rectangular houses, a roof and two slopes, a uniformity broken only by the adaptation of the physical characteristics of the site and the relation of the houses to the surrounding scenery (water/ fishermen, cultivated land/farmers) or an important building.

which in Chinese means ) chunambo (oyster lime). The bronze foundry directed by Manuel Tavares Bocarro was also situated there, and the quality of the production made Macao a centre of exports to Siam and China.

chunambo (oyster lime). The bronze foundry directed by Manuel Tavares Bocarro was also situated there, and the quality of the production made Macao a centre of exports to Siam and China.

Within the walls of clay mortar or chunambo the seventeenth century Portuguese city expanded, the buildings agglomerating in the main centres already existing in the sixteenth century: the zones of the Harbour, Santo António (St. Anthony)-Patane, Monte (Mount Fort)-Sé(See) [W. B. - 14 N. E. wall. ] and a more open and extensive axis along Central Street towards Penha Hill. Portuguese illustrations of the period, certainly the most exact, are few and sometimes incorrect and destitute of any reference scale. The drawing of the city reproduce in Volume II of Ásia Portuguesa (Portuguese Asia) by Faria e Sousa is very simplified and particularly emphasises the wall and defence posts. The plan of Macao drawn by Pedro Barreto de Resende to illustrate the manuscript by António Bocarro [°1594] entitled Livro das Plantas de Todas as Fortalezas, Cidades e Povoações do Estado da Índia Oriental (Book of the Plans of All the Fortresses, Cities and Towns of the State of East India) is more correct. It locates the principal religious buildings and marks the surrounding areas and zones if greater occupation, thus giving a picture of the whole complex and the areas forming part of it. In this work the city is described as a small settlement of traders, with a limited number of buildings in stone, brick and wood, situated to the Northwest of the peninsula near St. Paul's Church. There was another area with houses and commerce near St. Lawrence's Church which extended almost up to Praia do Manduco (Manduco Beach) [W. B. - 40 Praya Manduco. ]. The Chinese residential areas were near the temples and Praya Grande) had a large number of wooden houses. The area to the Northwest, adjacent to the Inner Port was probably the oldest area of occupation and was served by the Rua de Santo António (St. Anthony's Street), Rua de São Domingo (St. Dominic's Street) and Rua do Hospital (Hospital Street), built in the econd half of the sixteenth century. The occupation of the space to the Northwest probably dates from after 1590 and eveloped along Central Street, Rua de São Lourenço (St. Lawrence's Street) and Rua do Padre António (Father Anthony's Street). The zone of Barra also expanded in this period thanks to the settlement of a prosperous Chinese community which erected its buildings there. The streets were winding and the organisation of the plots indicated lack of previous planning. The city did not yet have a consolidated structure and the most important buildings were the churches and the Chinese warehouses. António Bocarro also refers to difficulties to obtain food supplies when the Chinese limited imports. According to the chronicler, the population consisted of eight hundred and fifty Portuguese and five thousand one hundred slaves, in addition to pilots and navigators. There were also Chinese Catholics whose numbers are not mentioned.

The popular Mercado Vermelho (Red Market)

at the junction of the Avenida de Horta e Costa (Horta e Costa Avenue) and the Avenida do Almirante Lacerda (Admiral Lacerda Avenue).

Institute Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macau) Photographic Collection, Macao.

The popular Mercado Vermelho (Red Market)

at the junction of the Avenida de Horta e Costa (Horta e Costa Avenue) and the Avenida do Almirante Lacerda (Admiral Lacerda Avenue).

Institute Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macau) Photographic Collection, Macao.

Illustrations in the works of foreign travelers such as the Atlas of Johannes Vingboons and the Diary of Peter Mundy, and Dutch and English engravings included in the route-rooks and collections of the period, are most very generalised and are often simply fanciful references where we can identify some constructions and the approximate form of the city. These constitute illustrations rather than accurate iconographic sources.

However, the description of Peter Mundy (1637) confirms that the city was organised around the churches. The houses with gardens, courtyards and terraces were similar to those of Goa and the two-sided sloping roofs were reinforced against typhoons. Peter Mundy refers to the development of Praya Grande, the fortifications and the occupation of Ilha Verde (Green Island). In 1638 Macao possessed six convents - Jesuit, Capucin, Dominican, Augustinian, Franciscan and Clare. There were two parishes, São Lourenço (St. Lawrence) and Santo António (St. Anthony), and the Ermida de São Lázaro (St. Lazarus Chapel) built outside the [city] walls for the lepers. In addition to the industries located in Chunambeiro there were also small silk factories annexed to the Chinese warehouses to the Northwest and Southwest of the settlement. Between St. Paul's Church and the sea, a rich population of Western merchants lived in fine houses.

The expulsion of the Portuguese from Japan in 1639 and the consequent loss of trade was a financial disaster for Macao which was partly compensated by the opening of other markets in Timor, Solor, Macassar (Makasar) and China.

In the middle of the eighteenth century the city was organised round Central Street, Rua Direita (Straight Lane), and the Largo do Leal Senado (Senate Square) into which two main streets and seven secondary streets emerged. Construction was unrestricted especially in the Portuguese zone where no regulations applied. The predominant characteristics of the urban structure were the open spaces round the churches and public buildings. The streets were irregular and the domestic architecture was limited to a style similar to that of Goa, with details altered by the Chinese artisans. The Portuguese population expanded towards the settlement of Barra. The houses occupied valleys and hills and generally had two floors connected by a wooden staircase. The predominant colour was white, enhanced by frameworks around doors and windows in yellow, pink and blue. The Chinese community occupied the Western sector and gradually expanded along the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour). They resided in areas of high density occupation in compact constructions forming combinations of shop/residence along very narrow streets. The houses were all made of brick, roofed with tiles, and their verandahs formed a complex of great diversity. Up to the nineteenth century this area was known as the Grande Bazar (Grand Bazaar) [W. B. - 15 Bazaar.].

At that period another community still existed in Macao - Persians, who were located in Barra.

When in 1685 the 'doors' of China were opened to foreign trade the mandarins thought of transforming Macao into a Chinese port. There followed a period of great uncertainty which terminated with the opening of a Chinese Customs post in 1688. Known as Hopu [Port. transliteration; Hebo], the oldest located at Praya Pequena, near Tercena Street and the most recent, the least important, at Praya Grande on the spot were the Treasury building stands today. These tributes were levied on ships ailing for Guangzhou and this had a negative impact on the economic life of Macao. To aggravate the financial situation the ground-rent was also increased and a residence tax imposed.

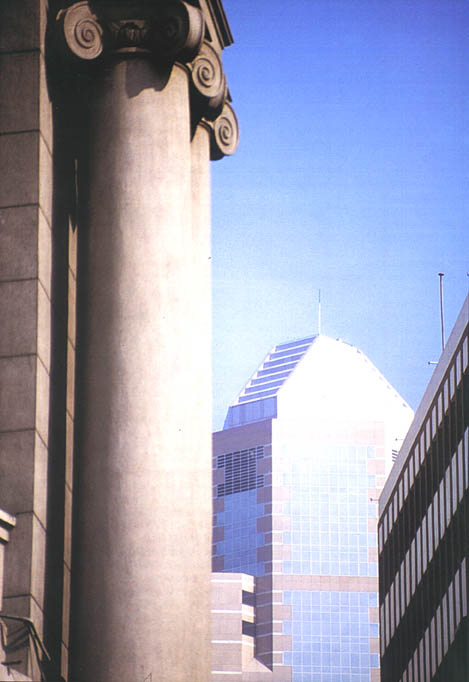

A Portuguese padrão facing the new headquarters' building of the Luso International Bank,

at Avenida do Doutor Mário Soares (Dr. Mário Soares Avenue).

Photograph taken in 1999 by Joaquim Castro.

A Portuguese padrão facing the new headquarters' building of the Luso International Bank,

at Avenida do Doutor Mário Soares (Dr. Mário Soares Avenue).

Photograph taken in 1999 by Joaquim Castro.

Originated and developed by the pragmatism of commercial momentum, to which it was always elated, the origin of the trading post and, later, the city of Macao cannot be traced to any erudite or traditional model of European or even Chinese roots. With the immediate implantation of the religious structures it was the buildings - churches and convents - which congregated and unified the population. Simultaneously, these small architectural complexes and the surrounding areas of a civic and religious character (the squares and churchyards) were reference points in the structure and image of the city. The erection of the walls contributed to the regulation and clarification of the structure, introducing a sense of unification in an irregular and apparently disorganised area.

§4. THE ARCHITECTURE -EUROPEAN AND CHINESE MODELS

Archeological remains of this period of the city's history are scant except for the iconographic documents already mentioned. Engravings in the works of Portuguese authors show the general physiognomy of the complex and the internal organisation of the settlement, but do give a correct idea of the details of the buildings.

The first graphical registers of the city contained in atlases and route-books of voyages of the seventeenth century, are generally fanciful and show little detail.

The first Portuguese constructions were rudimentary and precarious, similar to those generally constructed in the trading posts of Asia. The churches were of wood with a single nave, a simple chapel and a plain façade. They were gradually replaced by lath-and-plaster constructions at the beginning of the eighteenth century and only later became larger, ornamented stone buildings, embodying simplistically the spatial tradition and characteristics of the mannerists façades of Portuguese architecture.

If the recent arrivals brought with them architectural models and building methods from their country of origin, they found a large part of their work force and construction materials in the territory. It is not difficult to imagine that the first houses of the Jesuits and the merchants were Chinese constructions or that typically Chinese building methods were used in the first wooden churches. The commercial area, directly connected with maritime activities and a meeting point of the two communities, was probably, in architectural terms, predominantly Chinese. Outside the city, the temples and houses of the Chinese villages perpetuated the traditional architectural models of the region, characterised by a great simplicity of form and space.

The Hotel Riviera (Riviera Hotel), built in 1828, demolished in 1971.

Its dancing teas and 'American' dinners were important meeting points of the 'fashionable' local society.

Instituto Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macau) Photographic Collection, Macao.

The Hotel Riviera (Riviera Hotel), built in 1828, demolished in 1971.

Its dancing teas and 'American' dinners were important meeting points of the 'fashionable' local society.

Instituto Cultural de Macau (Cultural Institute of Macau) Photographic Collection, Macao.

In the sixteenth century European architecture began to spread concurrently with the development of Chinese traditions of space and construction. From these mutual influences resulted the original proposals which reflect the synthesis of local culture. Within the context of European architecture the religious buildings were influenced by two sources, Portugal and Spain. Four of the five convents built in that period were founded by religious Orders of the Spanish province- São Francisco (St. Francis) [W. B. -3 S. Francis.], São Domingos (St. Dominic) [W. B. -26 Church of S. Domingos.], Santa Clara (St. Clare)[W. B. - Church of Sta. Clara.] and Nossa Senhora da Graça (Our Lady of Mercy). The spatial model of the churches is the mannerist plan of the Jesuit type.

The church of the Convento de Sao Paulo (St. Paul's Convent), founded by the Jesuits at the end of the sixteenth century has affinities with other buildings of the same Order, such as the Igreja de São Paulo (St. Paul's Church) in Dio, The [Portuguese] State of India, and the Igreja de Jesus (Church of Lord Jesus) in Luanda, Angola. The primitive wooden construction was replaced by a larger, more carefully projected building which was inaugurated at Christmas in the year 1603 but was only completed in 1640. Of this vast monumental complex, most of which was destroyed by fire in 1835, there remains the long interior flooring and the imposing façade which rises above the steps. This façade of the Jesuitic type has no towers and is composed of three sections separated by three columns, the higher section having four floors and the lateral sections two floors. Local artisans worked on it. Portuguese, Chinese and also Japanese Catholics recently settled in the city, who all left signs of their work. The decoration includes Baroque elements of the Western type and images of Oriental origin - an exotic and original complex and a confluence of erudite international themes with Portuguese, Chinese and Japanese interpretations. The convent was a vast building of two floors disposed irregularly around a large courtyard.

The old wooden church of the Convento de São Domingos (St. Dominic's Convent), founded in the sixteenth century by Dominicans from Acapulco, was replaced by the present church in the eighteenth century. The principal façade is a typical composition of the period, the central section having three floors topped by a triangular pediment connected to the lateral, lower sections by means of a simplified wing. The Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Graça (Church of Our Lady of Mercy) of the Augustinian convent has a simpler, more classical façade.

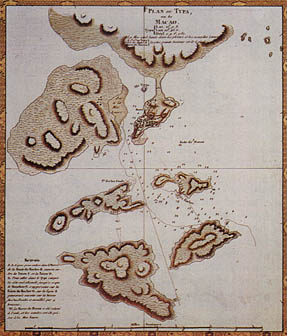

PLAN OF TYPA/OR/MACAO /Lat. 22°. 9" N. / Lon. 113.43" E./ Surveyed [...] 1780.

The plan clearly indicates Lappa Island (or of the Priests) - immediately to left of Macao -, abandoned by the Portuguese in 1780, and the Islands of Taipa and Coloane - facing Macao, at the bottom right -, occupied by the Portuguese during the time of Governor Ferreira do Amaral (1846-1849). Reprinted by the Direcção dos Serviços de Turismo (Department of Tourism- Government of Macau), 1986.

PLAN OF TYPA/OR/MACAO /Lat. 22°. 9" N. / Lon. 113.43" E./ Surveyed [...] 1780.

The plan clearly indicates Lappa Island (or of the Priests) - immediately to left of Macao -, abandoned by the Portuguese in 1780, and the Islands of Taipa and Coloane - facing Macao, at the bottom right -, occupied by the Portuguese during the time of Governor Ferreira do Amaral (1846-1849). Reprinted by the Direcção dos Serviços de Turismo (Department of Tourism- Government of Macau), 1986.

The sixteenth and seventeenth century parish churches, in spite of successive alterations and restoration works, still retain the spatial and formal characteristics of the period. Less elaborate than the convent churches, they have a single nave with side chapels and simple façades with towers _ one tower in the case of the Igreja de Santo António (St. Anthony's Church) and two in the case of St. Lawrence's Church and the Sé (See), the later being the largest of the three buildings. There were also small chapels adjacent to the military installations or at specific points of the city such as Nossa Senhora da Penha de França (Our Lady of Penha de França) [W. B. - 18 Penha Hill Church.], a simple building with a two-sided sloping roof (Our Lady of Guia), located within the fort of the same name, with a classical façade and solid buttresses, and the Igreja de São Lázaro (St. Lazarus' Church) which was later replaced by the present church.

The civil architecture also reproduced Western models but they were culturally less erudite and closer to Portuguese tradition, particularly experiences of The State of India and Malacca [Melaka]. Of the public buildings the Misericórdia (Misericordy) [W. B. -27 Church of Sta. Caza de Mizericordia.] the Senate and the centres of assistance represented by the hospital and the leprosarium were the most important. They were designed around a cloister-courtyard and had one, two or three floors in thick walls of brick and stone and two-sided sloping roofs. The main façade was characterised by large apertures. The houses were reminiscent of seventeenth century Lisbon palaces, large and heavy with a main floor over the storerooms and servants' quarters, balcony windows and simple iron grilles and a pediment above the central body. Access to the interior was through a courtyard from which the great staircase rose to the main floor. This plan remained in the traditions of Macao and can still be seen in houses of the period such as those at the corner of Rua de São José (St. Joseph's Street) and Rua da Prata (Silver Street). The interior decoration was inspired by Oriental taste and habits.

A complex of fortresses, small forts, bastions and a wall based on a modern fortified system was built in the seventeenth century, delimiting and defending the city. Although they had always prevented the construction of a solid defensive system, the Chinese authorities charged the Portuguese with the defense of the city and the territory which was constantly attacked by the Dutch.

From 1616 new constructions were planned to protect the coastline and, in 1622, the government levied a special tax on the ships of the 'Japan voyage' - the caldeirão (lit.: cauldron) - to subsidise the construction of the equipment required to transform the city into a modern citadel. The wall then erected was solidly constructed of clay mortar and included fortresses, forts and small forts. Starting from the Porto Interior (Innner Port) it linked up with the Fortaleza da Palanchica (Palanchica Fortress) and Fortaleza do Monte (Mount Fort), following to the Fortaleza de São Jerónimo (St. Hieronymus' Fortress), also called Fortaleza de São Januário (St. January's Fortress) and to the coast in the precints of the Convento de São Francisco (St. Francis' Convent) where the fort of the same name rose at the entrance of Praya Grande. Protecting the bay, it continued along the coast to the Fortim de São Pedro (St. Peter's Bulwark) [W. B. - 4 Fort of S. Peter. front of Govnrs. house.] and the Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora do Bom Parto (Fortress of Our Lady of Good Delivery; opularly known as Bomparto Fort) [W. ∫. - 5. Fort of Bomparto], rising thereafter to the zone of Penha where another fort, was erected. The wall then descended to the harbour, the whole extension of which was also protected by a curtain wall in which dock gates were opened.

General Plan of the City and the New Harbour of Macao 1927

JOÃO CARLOS ALVES - JOÃO BARBOSA PIRES

The expansion of the city and its new reclamation areas were decided by of the Comissão dos Portos de Macau (Commission of the Macau Harbours) created in 1918 with the specific purpose to implement the urban development of the city in associatioon with new harbour zones.

General Plan of the City and the New Harbour of Macao 1927

JOÃO CARLOS ALVES - JOÃO BARBOSA PIRES

The expansion of the city and its new reclamation areas were decided by of the Comissão dos Portos de Macau (Commission of the Macau Harbours) created in 1918 with the specific purpose to implement the urban development of the city in associatioon with new harbour zones.

Transit between the Portuguese city and the Chinese villages was through the traditional Porta de Santo António (St. Anthony's Gate) e da Porta do Campo (Campo Gate) [W. B. - 46 Gate of S. Lazarus or Campo.] in the section of the wall between the Fortaleza do Monte (Mount Fort) and the Fortaleza de São Januário (St. January's Fortress), and also through small gates and doors along the coast. Outside the walls of Guia Fort, built on the highest point in the territory and the Fortaleza de Santiago da Barra (Fortress of St. James of Barra; popularly known as Barra Fort) [W. B. - 6 Fort of Bar.], built on the extremity of the peninsula near the Chinese temple [of Ama], acted as advanced defence posts which controlled access to the port.

Some zones of the East coast of the peninsula, habitually frequented by the Chinese communities but easily accessible from the sea, such as Cacilhas Beach, were also protected by a wall. The regional defence was completed with a complex of batteries and a fort on Lappa Island.

Almost all these constructions were adjusted to modern defensive tactics and adapted the fortified system to the topography and extension of the different localities. The Fortaleza do Monte (Mount Fort), a simple, regular, polygonal construction is closer to erudite models without, however, having recourse to elaborate solutions such as the construction of trenches, simple esplanades or revelins. In some of them such as Guia Fort and the Fort of Our Lady of Penha de França, in addition to the small chapels or hermitages for use of the garrisons stationed in the soldiers' quarters, a cistern was generally constructed in the parade ground. During the seventeenth century, the majority of the curtain walls bordering Chinese territory were destroyed but some forts survived.

At the same time, traditional Chinese architecture persisted and developed, mainly in the form of new houses for the numerous Chinese population, which had increased considerably in the city, a new temple of Kun Yam Tong, [W. B. -9 Pagoda Nova.] near the old Kung Yam Ku Miu in the village of Mong-há and the renovation of Ma-Kok-Miu in Barra [W. B. -20 Bar Pagoda.]. The new Kung Yam Tong, which was to become one of the most important Chinese temples in Macao, is typical of the region of Guangdong, constructed in large rectangular units with a two-side sloping roof.

CHAPTER III

MACAO BETWEEN EAST AND WEST

§1. THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC

CONJUNCTURE AND THE

NEW RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN

EUROPE AND CHINA

THROUGH MACAO

The most significant events of the eighteenth century were the opening of the port of Guangzhou and the establishment of foreign trading Companies in Macao. With the publication of the [Chinese] Imperial Decree that in 1685 determined the opening of that port to foreigners, once a year during the fair, Macao ceased to be the only emporium for China's export trade and the Portuguese the sole intermediaries. This circumstance completely altered the economic development in the region. In a first phase the consequences were negative for the city's economy and only in 1718, when the Chinese were forbidden to trade (with the exception of the Macanese. Only when the number of Portuguese and Chinese ships registered in the city rose from four to twenty-three, did the opening of the fair and port of Guangzhou become important [to the economic prosperity of Macao]. The foreign trading Companies built warehouses on Shamian Island where their officials remained during the period of the fair as they were not permitted to enter Guangzhou itself. They negociated directly with the Mandarin Company, created in 1720, which held the monopoly of the local trade. The various European Companies and the one American, therefore established their headquarters in Macao which became an obligatory intermediate stage for access to Guangzhou.

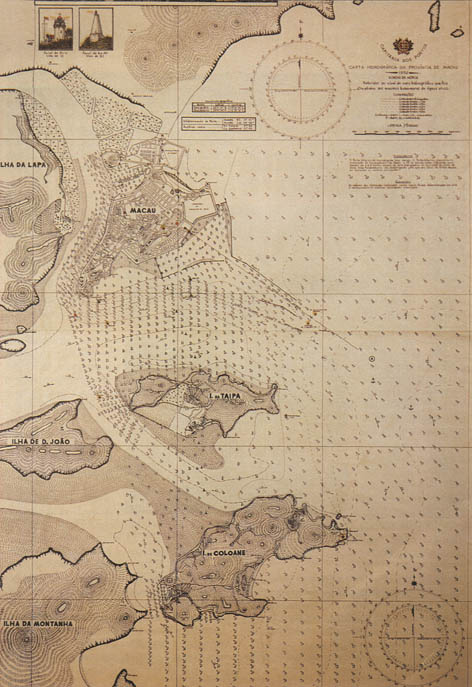

HARBOUR AUTHORITIES/HYDROGRAPHIC CHART OF THE PROVINCE OF MACAO / 1954

Note the recent reclamation area sharply destroying the western end of the previously preserved shoreline of the Baía da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Bay).

HARBOUR AUTHORITIES/HYDROGRAPHIC CHART OF THE PROVINCE OF MACAO / 1954

Note the recent reclamation area sharply destroying the western end of the previously preserved shoreline of the Baía da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Bay).

The Chinese mandarins forbade the passage of large ships, installed a Customs House in the city -The Grande Hopu (Great Hebo) of Praya Pequena - and created the post of Customs Mandarin of Macao who resided in the territory. In this manner they efficiently controlled access to estuary of the Pearl River and collected customs duties.

The economy and urban life changed with the presence of foreigners. A large part of the city's revenues was derived from taxes on and residence permits for foreigners. As a consequence of the new economic structure the city's revenues fell as the official structures were replaced by private Companies. At times of crisis the Senate was obliged to raise loans from the Church, Chinese traders and even the King of Siam.

Macao's resources in the eighteenth century also originated from customs and port anchorage duties. Commerce was in the hands of private Portuguese, Chinese and European entities. The traditional Chinese products, to which tea was added, transited through Macao. Here they were transferred from the small ships arriving from Guangzhou to large ocean-going vessels. The Portuguese merchants introduced snuff into China which was most appreciated. At the same time the clandestine commerce in opium and laudanum began to increase. This was carried out in French and British ships on the high seas but also brought financial benefits to the intermediaries of Macao.

The division of powers between the various Portuguese organisations was altered. The civil power became increasingly independent of the religious structures which were going through a period of crisis. With the expulsion of the Augustinian Friars from the city in 1712 as a result of the controversial Question of the Rites (which debated the concept of the Divine God and Emperor, as well as hierarchies of power), and of the Jesuits, in 1759, the field of action of the religious Orders was restricted. Their possessions were transferred to the Episcopal administration whose diocese was then restricted to the Chinese provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi.

The Governor took control of the Mount Fort where he traditionally resided but which was considered the property of the Jesuits. After 1767, measures were taken to acquire a suitable palace in the area of Praya Grande which was finally purchased in 1771, when government headquarters were definitely transferred to that area.

The building of the Quartel dos Bombeiros de Macau (Macao Fire Brigade),

at the junction of Estrada do Repouso (Rest Road) with Photograph taken around 1930.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

The building of the Quartel dos Bombeiros de Macau (Macao Fire Brigade),

at the junction of Estrada do Repouso (Rest Road) with Photograph taken around 1930.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

The powers of the Senate were clarified and defined by a Royal Warrant of 1712 which referred to the spheres of political government, which included all cases related to the well being of the city and the preservation of peace and tranquillity, and economic government which consisted in the collection of taxes and tributes and the spending of the revenues resulting therefrom. The procurator conferred with the mandarin and although a Royal Order issued from Lisbon in 1712 forbade obedience to local Chinese authorities, in practise proceedings were concerted by the intervention of the Senate.

The number of Chinese Catholic converts hand increased considerably and the Church appointed a representative called 'the Father of the Christians' to superintend problems arising between this group, the Portuguese and other Chinese. Controversy generally involved situations of dependence and servitude. The Senate finally intervened in 1703, forbidding Europeans to buy Chinese slaves for export, and in 1774, forbidding Chinese Catholics to use Western dress.

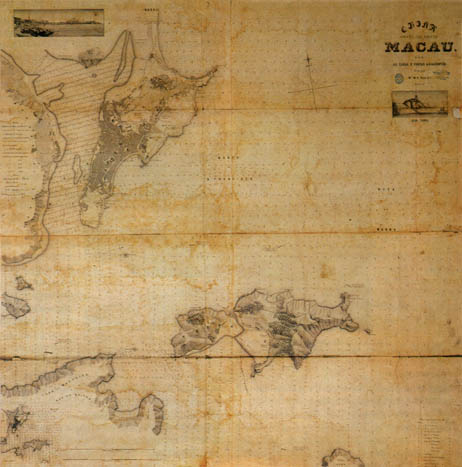

CHINA/EASTERN COAST/MACAO/WITH ITS ADJACENTS ISLANDS AND SHORES/Made by/ Mr. C. E., W. A. READ/1865-6-- detail.

In: CALADO, Maria-MENDES, Maria Clara-TOUSSAINT, Michel, Macau, Memorial City of the Estuary of the River of Pearls, Macao, 1985, p.84.

CHINA/EASTERN COAST/MACAO/WITH ITS ADJACENTS ISLANDS AND SHORES/Made by/ Mr. C. E., W. A. READ/1865-6-- detail.

In: CALADO, Maria-MENDES, Maria Clara-TOUSSAINT, Michel, Macau, Memorial City of the Estuary of the River of Pearls, Macao, 1985, p.84.

In this context the physiognomy of Macao changed from the economic, urban, populational and ethnic points of view, in a complex structure of co-existence powers. The Chinese gradually gained the ascendancy, to such an extent the Chinese Penal Code of 1779 contained rules for the administration of Macao and the Senate began to have Chinese chapas (Laws) translated and published and used specialised interpreters. The abandonment by the population of Lappa Island after 1722, [W. B. - 54 Ribeira Grande.; 55 Ribeira pequena.; 57 Pacsun] where the Portuguese legal structure was established by the religious Orders, brought the territory into the area of the city of Macao and Ilha Verde (Green Island), the remaining islands being used merely for anchorage and supply purposes.

At the end of the eighteenth century government structures were changed resulting in a division between the Senate and the government, while simultaneously the authority of the Church was re-established. The application of a new fiscal policy with the creation of a Portuguese Custom-House was also an important event. The progressive decline in revenue from the trading activities of the Portuguese in Macao resulted in the presentation of various reports and petitions by the local authorities to the governments of The State of India and Lisbon. The archaic empirical structures of the territory proved increasingly inoperable and ill-adapted to the international political and economic circumstances of the period: the doctrines of liberalism proclaimed free enterprise and competition to which the monopolistic traditions of a decadent Portuguese commerce could not respond.

Military parade on the yard facing the Quartel de São Francisco (St. Francis' Barracks).

The former Convent of St. Francis housed the first contingent of the Overseas Regiment in the early 1930s.

Photograph taken in the 1930s.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

Military parade on the yard facing the Quartel de São Francisco (St. Francis' Barracks).

The former Convent of St. Francis housed the first contingent of the Overseas Regiment in the early 1930s.

Photograph taken in the 1930s.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

Macao was not affected by the Pombaline reforms and specific measures on the local government and economy were only published in the reign of Queen Dona Maria I [°1734-r.1777-†1816]. These measures, decreed in 1783 and implemented in the territory the following year, were denominated Providências Régias (Royal Enactments). This document issued by the Lisbon government was based on an analysis of the structures of Macao, particularly as regards the economy, the government and the interrelation of organs of power. The solution indicated to solve the crisis were: - reorganisation of the government system with revised coordination and division of powers; reorganisation of commerce based on the fiscal system; the installation of a regiment of local militia; the re-establishment of the seminary and the reorganisation of the missions in Macao and China, with the participation of priests, missionaries and particularly Jesuits, with a view to developing diplomatic activities in the Court of Beijing. These changes tended to affirm Portuguese sovereignty in the area. The post of Governor began to be exercised by the same person for a minimum period of three consecutive years, renewable when considered advantageous and useful. Qualities of forcefulness were indicated as fundamental and it was recommended that preference be given to the appointment of military candidates. Although the Senate had local powers and representation in relations with the Chinese authorities its activities were regulated by means of obligatory consultations with the government. To reinforce the authority of the representative of the central power, a military force was formed of one-hundred sepoy and fifty gunners, recruited in Goa every six years. The Seminário de São José (St. Joseph's Seminary) [W. B. - 31 Church of S. Joseph] was established and handed over to the Lazarists in 1784, and the activities of the Church regained their former influence with the consequent reinforcement of religious authority. But the former prestige of the religious Orders was not restored and power was principally concentrated in the Bishop and the diocese. The Church purchased land and properties in the territory to increase its revenues and arrange space for the installation of missions, and in 1828 the St. Joseph's Seminary acquired Green Island. As a result of the restructuring of the religious authority the principal churches, of lath-and-plaster construction, were rebuilt in durable materials: St. Lawrence, in 1801; St. Augustine, in 1814 and St. Clare, in 1824.

The government, supreme representative of the Portuguese authority, was now supported by a military force that was more efficient in defence against pirates and reprisals by French and British ships than in actions against the Chinese. The administration of the territory also became more efficient and the governmental structure had greater stability which enabled it to initiate programmes of development and improvements in the city with some prospects of continuity, including the construction of roads and connecting thoroughfares between the Portuguese city and the Chinese settlements. In this context the construction of the Mong-há road and the earthworks and cuttings in the Penha Hill, with layout of roads, were particularly important.

An armilary sphere - one of the symbols of the Portuguese maritime discoveries - rendered in stone in the lawn of the inner garden of the Leal Senado (Macao Municipality).

The Senate powers and authority were apparently diminished, theoretically withdrawn by the government. In practice it continued to be the most representative organ as regards the Chinese regional authorities while the government dealt with the supreme representative of Empire diplomacy. In 1788 the Portuguese authorities recognised that the Senate represented the government in relations with the mandarins and practice became rule with legal support. The actuation of the Senate in local politics was so efficient and valuable that in 1818 the members of that body were given the right to be addressed as 'Senhoria' ('Lordship'). The statute was maintained during the first years of the Portuguese constitutional regime and lasted until 1834 when the functions of the Senate were limited to those of a Municipal Council.

The Portuguese Customs [W. B. - 38 Custom House.], created in 1784, had its own building near the harbour between Praya Pequena and Manduco Beach, in a extension of the Portuguese city. It had a body of officials who applied the respective statute, collecting anchorage dues from ships which entered the harbour and levying customs duties on imported merchandise.

The immediate effect of this fiscal policy was an increase in revenues. Ultimately the Customs authorities were subject to the Governor who controlled and administered the revenues, part of which reverted to the central government. Some of the money was spent on renovations to the city, particularly the harbour zone which was provided with a new quay and warehouses.

An important part of the revenue produced by customs duties was destined for the central government. and was paid annually accompanied by a financial report. Within the context of the new colonial policy which began to take shape at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the territories or colonies had to become profitable and contribute to the general expenses of the kingdom. For this reason measures for the reorganisation of official trade in Macao had positive results, principally within the general context of the Portuguese economy.

In addition to local control, which covered the harbour movements, the Customs also superintended the direct trade between Macao and Brazil. This trading line was only authorised in 1810, after the general opening of the Brazilian ports, and benefited from certain privileges and tax exemptions. The Oriental products carried to Rio de Janeiro were intended for the Portuguese Court which had recently left Lisbon and settled in that colony wowing to the instability resulting from the French invasions in Europe and particularly the Iberian peninsula.

An armilary sphere - one of the symbols of the Portuguese maritime discoveries - rendered in stone in the lawn of the inner garden of the Leal Senado (Macao Municipality).

The Senate powers and authority were apparently diminished, theoretically withdrawn by the government. In practice it continued to be the most representative organ as regards the Chinese regional authorities while the government dealt with the supreme representative of Empire diplomacy. In 1788 the Portuguese authorities recognised that the Senate represented the government in relations with the mandarins and practice became rule with legal support. The actuation of the Senate in local politics was so efficient and valuable that in 1818 the members of that body were given the right to be addressed as 'Senhoria' ('Lordship'). The statute was maintained during the first years of the Portuguese constitutional regime and lasted until 1834 when the functions of the Senate were limited to those of a Municipal Council.

The Portuguese Customs [W. B. - 38 Custom House.], created in 1784, had its own building near the harbour between Praya Pequena and Manduco Beach, in a extension of the Portuguese city. It had a body of officials who applied the respective statute, collecting anchorage dues from ships which entered the harbour and levying customs duties on imported merchandise.

The immediate effect of this fiscal policy was an increase in revenues. Ultimately the Customs authorities were subject to the Governor who controlled and administered the revenues, part of which reverted to the central government. Some of the money was spent on renovations to the city, particularly the harbour zone which was provided with a new quay and warehouses.

An important part of the revenue produced by customs duties was destined for the central government. and was paid annually accompanied by a financial report. Within the context of the new colonial policy which began to take shape at the beginning of the nineteenth century, the territories or colonies had to become profitable and contribute to the general expenses of the kingdom. For this reason measures for the reorganisation of official trade in Macao had positive results, principally within the general context of the Portuguese economy.

In addition to local control, which covered the harbour movements, the Customs also superintended the direct trade between Macao and Brazil. This trading line was only authorised in 1810, after the general opening of the Brazilian ports, and benefited from certain privileges and tax exemptions. The Oriental products carried to Rio de Janeiro were intended for the Portuguese Court which had recently left Lisbon and settled in that colony wowing to the instability resulting from the French invasions in Europe and particularly the Iberian peninsula.

in the <i>Praia Grande </i>(Praya Grande). </b>

</JZ>

<figcaption>This front wing was added to the old building in 1872-74 and demolished in 1946.

The <i>Novo Palácio das Repartições </i>(New Government Palace) as it still stands was inaugurated on the 30th of June 1954. </figcaption></figure>

<p>

In addition to official Portuguese, foreign and Chinese trade, the latter under mandarin control, there was, on a reduced scale, the Macao trade practiced by the inhabitants of the territory. Although the Royal Enactments had centralised the most profitable trade, leaving less scope for private initiative, the creation of the <I>Casa de Seguros </i>(lit.: Insurance House) or <i>Casa Forte </i>(lit.: Strong House) in 1817 improved prospects, permitting small traders and companies to enroll and cover their risks. These merchants traded principally with the Chinese in the villages of the region but also frequented the ports of Manila, Timor and Siam. The paid taxes for use of the harbour and on the products in circulation but a large part of their trading activities and movements remained beyond the reach of the fiscal authorities. The largescale opium trade in the hands of the French and British was frequently supported by local merchants who facilitated transactions. Expressly forbidden by the Chinese authorities, in 1828, it continued clandestinely in a circuit dominated by the foreign Companies who brought the product from India and the coasts of Asia and introduced it into China through the merchants of Macao. The transactions were effected on distant stretches of the coast outside the control of the Portuguese and Chinese authorities. Initiated about the year 1720 it was at first tolerated by the mandarins in exchange for the payment of fifty Patacas a box, but it was officially forbidden by the Imperial Laws. By the second half of the eighteenth century it had become common, gradually intensifying thereafter until in the first quarter of the nineteenth century it produced the greater part of trade revenues, which were beyond official control and did not revert directly to the entities and organisations responsible for the administration of the city. The other products in circulation were traditional ones: tea, pearls, silk, porcelain, rice and sandalwood, the monopoly of the latter having terminated in 1785.

</p>

<p>

It is thus evident that it became an increasingly regular and accepted situation for economic structures to co-exist with the exercise of illegal trade carried on by small local merchants, whose profits were calculated to be considerable but were impossible for the fiscal authorities to control and account for. As result there was a certain prosperity among the small number of Macao families and a progressive accumulation of wealth, mentioned by sources of the period but only expressed publicly in the new constructions of the second half of the nineteenth century.

</p>

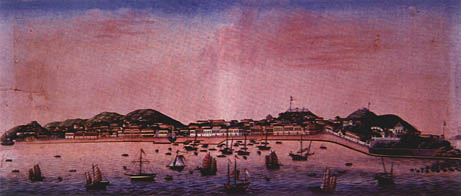

<figure><img src=) The Peninsula of Macao.

The so-called 'MASTER OF THE FIRE' (Chinese School).

Ca1815. Oil on board. 11.0 x 15.0 cm

The Peninsula of Macao.

The so-called 'MASTER OF THE FIRE' (Chinese School).

Ca1815. Oil on board. 11.0 x 15.0 cm

§ 2. THE DYNAMICS AND STRUCTURE OF

THE URBAN SPACE DURING THE

EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

In the eighteenth century Macao maintained a spatial structure identical to that of the former period. The Portuguese area developed between the St. Anthony's Church, Patane, Mount Fort, the St. Paul's Church and the sea. The wealthier section of the population was concentrated here, essentially comprised of merchants and some officials of the government which was still installed in St. Paul's).

Portuguese and other foreigners also settled in the St. Augustin's Convent, the Convento de São José (St. Joseph's Convent) and the Convento de São Lourenço (St. Lawrence's Convent). The Central Street was long and linked the See to the chapel Our Lady of Penha de França. It was later extended to Barra but in first half of the eighteenth century occupation extended to St. Lawrence's. Here there were the characteristics of an urban periphery with large gardens and small kitchen-gardens attached to the houses. Between St. Lawrence's and the coast there was a commercial area, the Bazarinho (Little Bazaar) which supplied the residential area mentioned above. This area circulated via the Rua da Casa Forte (Strong House's Street) and Rua da Praia do Manduco (Manduco Beach Street) which was very frequented and formed part of the area of prostitution, an activity still recalled by the name of the Travessa da Maria Lucinda (Maria Lucinda's Alley), proprietress of one of the most famous 'houses' of the period. At the end of the century, around 1797, Manduco Beach began to be used as a wharf.

The old Hospital de São Januário (St. January's Hospital).

Built in 1920 by the Baron of Cercal and the Captain Dias Coelho in a hybrid neogothic-cum-neoclassical style. It was one of the best example of the grand eclectic architecture which blossomed in Macao during the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Photograph taken in the 1920's.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

The old Hospital de São Januário (St. January's Hospital).

Built in 1920 by the Baron of Cercal and the Captain Dias Coelho in a hybrid neogothic-cum-neoclassical style. It was one of the best example of the grand eclectic architecture which blossomed in Macao during the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Photograph taken in the 1920's.

João Loureiro Collection, Macao.

As in the previous century the Portuguese city continued to be organized around the churches and convents surrounded by ample, open, public spaces, in contrast to the Chinese zone situated to the North between St. Augustine, St. Paul's and the sea. Here elongated blocks, crossed by narrow streets and alleys were filled with two-storey houses, the lower floors occupied by the family business and small artisan industries. The alleys generally served for the circulation of the pedestrians but some were cul-de-sacs and acquired a certain degree of privacy. North of this complex was the Praya Pequena Street where the most important Chinese Custom House was situated. Here too were concentrated the Chinese who worked on the 'teang fai', small, swift ships that crossed the China seas. The whole of this area constituted the Grand Bazaar, the fulcrum of which St. Dominic's, the Street of the Merchants, the Eastern ends of Street of the Herbalists and Rua das Estalagens (Street of the Inns), and the Rua da Palha (Straw Street), the name of which derived from the concentration there of establishments selling that product. Further to the North there was another urban area between the St. Anthony's Church and the sea, which extended to the Rua do Tarrafeiro (Street of the Fishermen) and Rua do Botelho (Botelho Street). Near the later proliferated the tancas [Guang.] (house-boats) the population which caught shrimps with tarrafas [Port.] (nets), an implement which originated the present name of the street. Chinese artisans resided in the area between the house-boats and the church and their activities are recalled in the names of the Rua dos Adufos (Street of the Adobes) and Rua dos Carpinteiros (Street of the Carpenters). Southwest of St. Anthony's the Western structure was maintained. There were large squares with religious buildings - St. Paul's, St. Francis, St. Clare and the See - with ample space around them. The streets were irregular but there were two main thoroughfares: one passing the Senate which linked Central Street to St. Paul's Street, the other which linked this fortress with St. Francis. The Dutch East India Company in the present Largo da Companhia (Square of the Company) in the Northern area of St. Paul's. Known by the Chinese as the 'Dutch Garden' it was an area related to the countryside. References to Portuguese houses with kitchen-gardens, dating from 1764, confirm the peripheral function of this complex.

Within the Western-type structure mention should be made of the consolidation of the urban complex of Praya Grande, between the forts of St. Peter's and Bom Parto. It had a wide avenue parallel to the sea, perpendicularly cut by side streets connecting with Central Street. The wall was partially destroyed, there remaining only the Eastern stretch between St. Francis and St. Paul's.

The Praya Grande.

Unknown Chinese artist.

Ca1835. Guache on paper. 0.54 x 1.20 m.

The Praya Grande.

Unknown Chinese artist.

Ca1835. Guache on paper. 0.54 x 1.20 m.

The growth of the population of European origin was not sufficient to require expansion of the city beyond the limits already defined in the seventeenth century. On the other hand, the Chinese population increased by four-thousand, mostly in the villages of the Inner Harbour. St. Lazarus continued to be the centre for settlement of Chinese Catholics. Long-T'in-Ching and Mong-há remained agricultural villages, between them stretching an extensive cultivated plain which was the principal agricultural centre for the supply of Macao. The population of the village of Barra on the Inner Harbour, a fishing village built around the Temple of Ama, was increased by the settlement of a community of Persian traders from Guangzhou. To the North of the Largo de Santo António (St. Anthony's Square) were the riverside settlements of Patane, Sa Kong and San Kiu which were linked to maritime activities. Important for their shipyards and timber deposits they had a numerous population living in wooden huts and houses, with thatched roofs, supported on stakes, reminiscent of lake dwellings. They were built in rows but formed a disorganised complex. These villages were very unhealthy areas with malarial infections, conditions which existed along the Sankiu Channel which crossed Patane to the Sá-Kong plains.

§ 3. NEW COMPONENTS OF THE ARCHITECTURE

During the eighteenth century new architectural models of European origin were introduced, principally in civil architecture. The most significant aspect was the construction of buildings along the Bay of Pray a Grande forming a wide street or coastal promenade. These were Company installations, houses of the aristocracy and the Palácio do Governo (Government Palace). The façades opened on to the exterior by a sequence of balconies on the first floor, the buildings having a certain degree of monumentality and some decorative details. In addition to Portuguese traditions there were British influences displayed in signs of late classicism.

As a result of the increase in the Chinese population at this time, many new traditional-type houses were constructed in the area of the Inner Harbour, especially in Little Bazaar and in the areas adjacent to the upper city occupied by the Portuguese.

Some eighteenth century religious constructions and Baroque tendencies such as the Church of St. Joseph's Seminary, constructed at the top of a wide stairway. The undulated facade with two towers and a pediment, also undulated, is horizontal and irregular, revealing the centralised plan of Baroque style. A monumental cupola covers the transept. In this period a new chapel was built and dedicated to Bom Jesus (Holy Jesus) [W. B. - 23 Mato de bom JESUS] on a site near that of Our Lady of Penha de França. New temples were built in the Chinese area such as those of Ling Fong, Lin K'ai, Soi Ut Kum and Kuan Tai Ku.

During the first half of the nineteenth century the structure of the city gradually altered, the architecture being characterised by a curious synthesis of traditions and innovations. New areas were created by earth-fills in the areas of Praya Pequena and Manduco Beach, establishing a continuity of the coastline and permitting new construction. About ten blocks were constructed in regular lines between Avenida 5 de Outubro (Fifth of October Avenue) and Rua do Guimarães (Guimarães Street). These buildings, which still exist today, were the first to be designed on regular geometric lines.

Another important aspect of the organisation of the city was the installation of the cemeteries -the Catholic in 1837 in the ruins of St. Paul's, the Protestant, in 1821, and that of the Parsees in 1829. At the same time, outside the traditional limits of the city, in Penha, Barra and Guia, chácaras [Port.] (vast properties with a Summer residence) began to appear.

A part of these new tendencies was the creation of the Jardim Botânico (Botanical Gardens), presently the Luís de Camões Garden which was the forerunner of a widespread implantation of gardens and green areas in the city during the second half of the nineteenth century.

The ultimate phase of the period of foreign Companies in Macao corresponded to the spread of Neoclassical models, an erudite tendency which left its mark on the architecture. José Tomás de Aquino was one of the most prominent architects. He designed various houses, theatres and churches, reconstructed Joseph Jardim's residence in Rua do Bom Parto (Bom Parto Street) in 1834 and built a new Ermida de Nossa Senhora da Penha de França (Hermitage of Our Lady of Penha de França) in 1837, the Teatro Luso-Britânico (Luso-British Theatre) in 1839, his own house on the Santa Sancha estate (now the Governor's residence) in 1846, and the Palacete da Flora (lit.: Flora Stately House) in 1848.

§ 4. ASPECTS OF LOCAL HISTORY AND URBAN LIFE

References to daily life in Macao at the end of the eighteenth century and first half of the nineteenth century are abundant and diverse and appear in official government and Senate documents, in descriptions by foreigners visiting the city or living there and in scientific and learned works. The most important of these works are: Voyage de l'Aambassade des Indes Orientales Hollandaises vers l'Empereur de la Chine dans les années 1794 et 1795 (The Travels of the Dutch East India to the Emperor of China in the Years 1794 and 1795), Philadelphia, 1798, Voyage en Chine ou Journal de la Dernière Ambassade Anglaise à la Cour de Pékin (Travels in China or The Journal of the Latest English Ambassy to the Court of Beijing), Paris, 1819, and principally, The Diary of Harriet Low, written in the 1820's and 1830's and published in 1900 by Catherine under the title My Mother's Journal. The visual documentation of this period, represented by watercolours, engravings, drawings and paintings is also numerous and registers important details of scenes from daily life and certain environments of the city. The watercolours by Robert Elliot and Marciano Baptista, the drawings and lithographs by Auguste Borget, George Chinnery, W. Heine, I. Clarck and various works included in museum collections portray aspects of urban life and landscape with accuracy and expression. Topographical surveys resulted in the plans of 1808, 1820 and 1838 which form an accurate basis for an understanding of the urban expansion and reorganisation of the traditional areas.

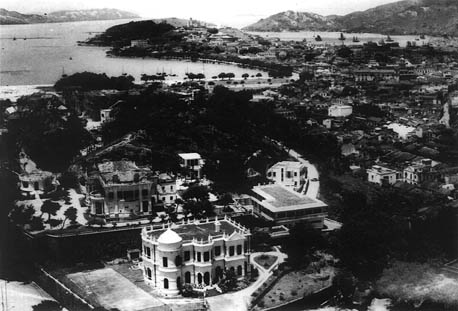

South-southeastern panoramic of the peninsula of Macao taken from the heights of Colina da Guia (Guia Hill).

In the foreground is the so-called 'Casa Branca' ('White House')- presently the Convent of the Precious Blood [of Jesus Christ] - a private house drawn in 1916-1917 by the British architect John Lemn. Behind it and slightly to the left, is another private residence, the so-called 'Vila Alegre' ('Jolly Villa') - presently, the Ling Nam School - drawn in 1917-1918 by the Portuguese architect José Tomás Silva. These town mansions were among the best examples of many built in the Portuguese colony during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Photograph taken in the late 1940s.

RC Photographic Collection.

South-southeastern panoramic of the peninsula of Macao taken from the heights of Colina da Guia (Guia Hill).

In the foreground is the so-called 'Casa Branca' ('White House')- presently the Convent of the Precious Blood [of Jesus Christ] - a private house drawn in 1916-1917 by the British architect John Lemn. Behind it and slightly to the left, is another private residence, the so-called 'Vila Alegre' ('Jolly Villa') - presently, the Ling Nam School - drawn in 1917-1918 by the Portuguese architect José Tomás Silva. These town mansions were among the best examples of many built in the Portuguese colony during the first decades of the twentieth century.

Photograph taken in the late 1940s.

RC Photographic Collection.

In his description of Macao, José Guimarães de Freitas refers to the aspect of the city: "[...] the streets are narrow but paved and the drains under them rapidly draw off the rain water. The city is walled to the North and the South. Here there are two gates which communicate with the countryside. Between the gates to the North raises the Fortaleza de São Paulo do Monte (popularly known as Mount Fort) [W. B. - 1 Fort of St. Paul or Monte.]; to the South there are two forts one of which is the Forte de Nossa Senhora da Penha de França [Fort of Our Lady of Penha de França]; three fortresses defend the bay at the entrance to which is Barra Fort; on a hilltop is Guia Fort. A long quay called Praya Grande has a charming wall; the Western part overlooks the harbour and an island formerly donated to the Jesuits [...]" (FREITAS, José de Aquino Guimarães, Memoria sobre Macau, Coimbra, Imprensa da Universidade, 1828, pp.11-13 [sic]).

The Catholic population was distributed between the See, St. Lawrence's and St. Anthony's which had two-thousand one-hundred and thirty, one-thousand seven-hundred and twenty, and four-hundred and fifty six inhabitants, respectively. The Chinese totaled eight-thousand but outside the walls there were twenty two-thousand pagan Chinese.

The Portuguese city was also inhabited by foreigners who introduced new habits. The Portuguese - military, merchants and administrative personnel - were Catholics and the churches continued to be centres of collective life. The foreigners - merchants and their families - were mostly Protestants and constructed their own places of worship and cemeteries.

The Macanese which lived in the Portuguese city had assimilated many Western habits, especially as regards behaviour, dress and style of life. In the opinion of foreigners this city was elegant with big houses and gardens.

Bird's eye view of the Largo do Leal Senado (Leal Senado Square).

In the foreground, the rooftops of the Edifício Ritz (Ritz Building); in the middle ground the imposing headquarters of the Correios, Telégrafos e Telefones [CTT] (Post Office, Wireless and Telephones), built in 1931; to the left, the new revivalist façade of the Misericórdia (Misericordy); and in the right the Avenida Almeida Ribeira (Almeida Ribeiro Avenue) continuing towards the new reclamation areas at the western end of the Praya Grande Bay.

RC Photographic Collection.

Bird's eye view of the Largo do Leal Senado (Leal Senado Square).

In the foreground, the rooftops of the Edifício Ritz (Ritz Building); in the middle ground the imposing headquarters of the Correios, Telégrafos e Telefones [CTT] (Post Office, Wireless and Telephones), built in 1931; to the left, the new revivalist façade of the Misericórdia (Misericordy); and in the right the Avenida Almeida Ribeira (Almeida Ribeiro Avenue) continuing towards the new reclamation areas at the western end of the Praya Grande Bay.

RC Photographic Collection.

Some idea of the living conditions of the inhabitants can be obtained from the transcription of an extract from a letter written in the 15th of May 1829 by the procurador (Attorney) of the city of Macao to the mandarin of the Casa Branca (White House) [W. B. -7 Caza Branca, residence of a Mandarine. ] who asked about life and trade in Macao: "The city has less population and less houses. The Emperor having permitted the Portuguese to live there, between the Border Gate and Barra, they only occupy a small area, leaving the beaches free for unloading and concentration of their ships and using some fallow ground for their market-gardens. But during the last twenty years the Chinese population, which was eight hundred souls, has grown to forty-thousand; market-gardens and fields rented from the Chinese were cultivated. The Chinese took the fallow ground for their shops and rented many Portuguese houses which they kept without paying the rent (for example those of St. Augustine, St. Paul's Street, Gregório Abreu and Praya Pequena). These the Chinese took, building many huts even in places that were streets. Thus they continue to Barra and Patane where formerly there were houses of the Portuguese who are now restricted to Praya Grande and the houses in the centre of the city, rebuilding them when they are old; they do not take lands or their churches. The Bazaar which was formerly outside the city is now within it, as also a multitude of Chinese houses, it being impossible to distinguish those of good and those of bad men [...]."

In monsoon seasons the city suffered catastrophes which destroyed the quay and main buildings. In 1824 a fire destroyed a large part of the Convento de Santa Clara (Convent of St. Clare) and, in 1825, another ruined that of St. Paul's and its church. This nucleus, belonging to the Jesuits, had already been partly dismantled in 1788 when the library and workshops were demolished. In 1835 another fire swept through the church which was reduced to the façade and walls. It was later demolished as being irrecoverable, except for the principal façade of the church and the stairway. The interior of the church was used as a Catholic cemetery from 1838 until the construction of the new Cemitério de São Miguel (St. Michael's Cemitery). In 1831 a typhoon hit the area causing damage in the zone of Praya Grande. The promenade was widened, the protective walls strengthened and some buildings were reconstructed in the Neoclassical style.

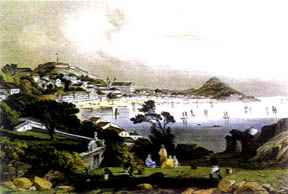

View of the Praya Grande taken from the Penha Hill.

WILLIAM HEINE.

1853. Coloured litograph.

In: HUNTER, W. C., An American in Canton (1825-44), Hong Kong, Derwent Communications Ltd., 1994, chap. III, [p. n. n.].

The Chinese urban area expanded and included new blocks of buildings erected in the area between the present Street of the Merchants and Rua Camilo Pessanha (Camilo Pessanha Street) and the Travessa da Cordoaria (Alley of the Rope Factory), Travessa do Pagode (Pagoda Alley) and Travessa do Armazém Velho (Alley of the Old Warehouse). To the West of this complex was bordered by the present Fifth of October Avenue, to the South by the present Avenida Almeida Ribeiro (Almeida Ribeiro Avenue) and to the North-Northeast by Praya Pequena Street, now known as Tercena Street. The house of the mandarin and the Hebo (Chinese Customs) of Praya Pequena were situated here. In front of this complex was the fish market.

The long blocks of buildings crossed by alleys in the area between the Street of the Inns, Camilo Pessanha Street, Street of the Merchants and Almeida Ribeiro Avenue, were occupied by Chinese houses, bordered to the Southeast by the Grand Bazaar (an area presently occupied by the Mercado de São Domingos (St. Dominic's Market) and by carpenters shops mainly connected with maritime activities. These activities also resulted in the establishment of a considerable number of ship owners in the Manduco Beach, near which the Portuguese Custom House was installed in 1783, in the street of the same name.

The Chinese villages continued to maintain an independent life and the surrounding fields supplied the Portuguese city. Green vegetables and fruit were abundant but meat, a basic element in European diet, was scarce. The temples were the principal buildings in these settlements. The Chinese cemeteries were built in the fields or on slopes and were a symbolic, religious space of great importance to this community. In addition to the tombs of wealthy families that were buildings with several rooms, these places were occupied by innumerable simple graves that were equally sacred and vital to the population and these areas were considered of public utility.

Front elevation of the Leal Senado (Senate Municipal Council).

The building façade- which has been kept to the present - is the result of a restauration proposed by Engineer Valente Carvalho and executed in 1939. This design incorporates little adjustments to the alterations made in 1876 to the previous façade of 1872 - when the building was considerably rebuilt after the devastating effects of that year's typhoon.

RC Photographic Collection.

In the first quarter of the nineteenth century a significant event was the appearance of a local periodical. This was the newspaper "A Abelha da China" ("The China Bee") which first appeared in the 12th of September 1822 under the orientation of a Dominican Friar. In 1824 it became the "Gazeta de Macau" ("The Macao Gazeteer") and in 1834 the "Crónica de Macau" ("The Macao Chronicle"), gradually becoming more regional in character, in the 9th of July 1836 the "Macaísta Imperial" ("Imperial Macanese") appeared and was published for two years. In 1838 publication was initiated of the "Boletim Oficial do Governo de Macau" ("Official Bulletin of the Government of Macao") which carried official information and government programmes.

With its own peculiar way of life, exotic and attractive to most Europeans, the city of Macao lived out the last phase of the colonial period of the sixteenth century origin and began to seek new directions that would lead to the expansion of the urban area and the fusion of the two original centres, with consequent transformations in the culture and urban landscape.

VIEW OF MACAO FROM THE MONTE FORT NEAR ST. PAUL'S CHURCH

[?] MEDELEY

1840. Coloured litograph.

Museu de Arte de Macau (Macau Museum of Art) Collection

CHAPTER IV

MACAO FACES THE FOUNDATION OF HONG KONG AND THE POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATIONS IN THE REGION AND IN THE WORLD

§ 1. THE END OF MACAO AS THE POLE OF COMMERCIAL EXCHANGES BETWEEN CHINA AND THE WEST

The opening of the ports of China to the West and the establishment of the British in Hong Kong had decisive repercussions on the evolution of Macao from the nineteenth century onwards.

The Convention of Chuenpi which terminated the Opium War between Britain and China was ratified by the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842. The 'opium question' had existed since the seventeenth century and the revenue from the commercialisation of this product was of considerable importance to the economies of European countries, particularly Britain, and the economy of Macao. Official Chinese legislation had always forbidden the import and consumption of opium and in 1838 a Chinese Imperial Decree expelled all British subjects from the country and the port of Guangzhou was closed to British Companies. By 1842 the conflict had been solved in favour of the Britain who demanded the payment of reparations from China, obtained the immediate opening of the ports of Guangzhou, Amoy, Fuzhou, Shanghai and Ningbo to European trade and also obtained the cessation of land for the installation of a commercial establishment. In 1843 the territory of Hong Kong was ceded and the British founded the city of Victoria.

For Macao the end of the long period of three centuries in which the territory was the only commercial emporium between China and the West was on sight. Replaced by Hong Kong, Macao suffered the consequences of the international conjuncture, accentuated by the rapid growth of the British nucleus. The foreign Companies established in the Portuguese city were attracted by the dynamism of the new emporium which had a large harbour. In 1845 the British consulate in Macao was closed and the European and American commercial and diplomatic representations followed suit. Some stayed on for a few years, using Macao more as a diplomatic than a commercial centre, and in 1844, the Sino-American Treaty was signed in the city, in the Kun Ian Temple.

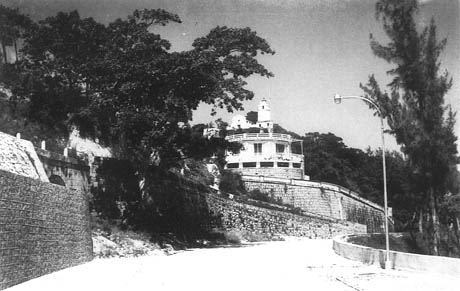

The Estrada de Cacilhas (Cacilhas Road) near the Centro Hospitalar Conde de São Januário (St. January's Government Hospital).

In the distance, the Capela de Nossa Senhora da Guia (Chapel of Our Lady of Guia) and its adjacent lighthouse - the first in the China coast -crown the Colina da Guia (Guia Hill).

RC Photographic Collection.

The foreign Companies took with them many of their Macanese officials and the latter were fundamental in the formation of the commercial and cultural structures of Hong Kong. These officials served as interpreters in contacts with the Chinese. Many merchants from Macao, who traditionally operated in the region and were acquainted with the dynamics of the complex process of relationships, also moved to the British city with their families. Others joined the banks and insurance companies established in that port and some supported the incipient cultural structures. In the nineteenth century there were large numbers of Macanese in the city of Victoria.

The British emporium supplanted Macao not only in the business of importing Chinese products and manufactured goods but also in the placing of Western products in the region. The Portuguese city thus passed from a privileged situation to one of dependence. A shipping line (first sail, then steam) was organised between Hong Kong and Macao for the transport of passengers and goods. Communications were perfected in new fields supported by modern technologies and in 1920 the telegraph was inaugurated between the two cities. For Macao the connection with Hong Kong signified an approximation to European standards and life styles.

The regulations of the city and the port of Macao, approved in 1842, reorganised the old methods of operation, adjusting them to the conditions arising from the opening of other ports on the Chinese coast, in addition to Guangzhou, and did not anticipate the consequences of the establishment of Hong Kong. Macao was only designated a free port in 1845, a late measure for by that time the British port was already equipped and operating, attracting foreign capital and the ships of the great European and American lines.

Although the immediate consequences of the foundation of Hong Kong were catastrophic the economy of Macao sought to adjust to the new equilibrium in the region where to the present, the new centre has reigned supreme. Trade in coolies and opium were the basis of the territory's economy in the nineteenth century which were later joined by the first modern industrial structures.

The Hotel da Bela Vista (Bela Vista Hotel) shortly after its innauguration in July 1890.

Underneath the imposing structure of the former private residence are the simple structures of the Fortaleza de Nossa Senhora do Bom Parto (Fortress of Our Lady of Safe Delivery) garrison and the remnants of the original protecting ramparts.

§ 2. RELATIONS BETWEEN THE CHINESE AND PORTUGUESE SOVEREIGN POWERS IN MACAO

The implantation of liberal constitutionalism in Portugal after 1834 originated structural transformations of the political, administrative, juridical and commercial regime which affected the colonial territories.

The most important measures in this area were:

--the revision of the colonial administration leading to the centralisation of power and the effective affirmation of Portuguese sovereignty,

--the organisation of the provinces and the extension of the municipal regime to all territories, and

--the abolition of the religious Orders with the consequent secularisation of their possessions which were transferred to the state and institutions or sold to private entities.

In 1844 Macao was separated from Goa and became a province which included Timor and Solor. The territory remained in this administrative situation until 1850 when two independent provinces were formed. After 1870 the Province of Macao and the Province of Timor were permitted to elect two deputados (Deputies) to the Cortes (National Assembly). The history of these two territories is interrelated in the nineteenth century for administrative and economic reasons. On some occasions they made a joint contribution to the revenues of the general budget of the kingdom.