§ 1. INTRODUCTION]

Macao and Hong Kong face each other across the water from their locations on either side of the Zhujiang• (Pearl River) estuary. In ancient times, as now, the major coastal fishing villages and ports in the southern part of the Zhujiang estuary abounded in fish, salt and incense and exported pottery and furniture and other renowned commodities produced there, playing a major role in foreign trade and cultural exchange between China and the outside world. Their history is a glorious one.

Like Hong Kong, Macao has been part of Chinese territory since ancient times, as is clearly recorded in the annals of history. However, at the present time certain non-Chinese scholars are claiming that Hong Kong and Macao were uncultivated land before Europeans arrived in China. This approach was first posited as far back as the 1930s and 1940s, when painted pottery from the Neolithic period was discovered Tai Wan• (Dawan) in Hong Kong• (Xianggang) and in the sand dunes north of Shanwei, • in Haifeng• county, Guangdong. The archaeologist who made these discoveries suggested that the Hong Kong - Haifeng pottery had "[...]come south [...]", adapting the phrase describing the "[...] coming west [...]" of Chinese porcelain. (1) Although long since disproved by the Yangshao wenhua• (Yangshao Culture) of the Huanghe• (Yellow River) basin, the Daxi wenhua• (Daxi Culture) of the Changjiang• (Yangtze River)• basin, and the definite link between the painted and white Daxi Culture pottery and the Dawan• Culture of the Zhujiang estuary, (2) the negative influence of erroneous theories of this kind has not vanished completely from the scene.

The present article addresses this issue anew, bearing in mind the fact that the quantity of archaeological discoveries in Hong Kong and in the Zhujiang estuary far outstrips those of Macao (the author considers that the key obstacle in this regard is the absence in Macao of any formal legislature to protect archaeological relics and the lack of any training for Macao to educate its own archaeological experts), to the extent that in Macao, knowledge of local history before the Tang• and Song• dynasties has, until now, been confused and hazy. Not only is Macao physically much smaller than Hong Kong, but historical documentary evidence is also far more scarce. The author believes, however, that on account of its advantageous geographical location and abundant natural marine resources, Macao was without doubt the ideal place for people from the mainland to turn to in search of resources and living space, leaving historical relics behind them in their wake. Furthermore, Macao and Hong Kong are important ports connecting the interior of China, Guangzhou• and the Zhujiang estuary with international traffic through the South China Sea, and through history this maritime trade must have left behind many historical relics, which still remain to be investigated and researched. The present article approaches this topic with reference to cultural archaeological discoveries.

§ 2. MACAO'S GEOGRAPHICAL LOCATION AND HISTORICAL EVOLUTION

Macao is located in the south central part of Guangdong province, in the south-west of the Zhujiang estuary, contiguous with the Gongbei• district of Zhuhai• to the north, 105 km from Guangzhou, across the water from the islands of Wanzi• and Hengqin• off Zhuhai to the west, and across the Zhujiang estuary from Hong Kong, which lies 61 km to the east. The South China Sea lies beyond the Wanshan• islands to the south.

Macao consists of the Macao peninsula, plus the islands of Taipa• (Dagzi dao) and Coloane• (Luhuan dao / Jiuao shan), an area of 16,779 km2 (of which the Macao peninsula accounts for 5,966 km2, Taipa 3,794 km2 and Coloane 7,019 km1). The highest point in Macao is Tashitang Shan• at 176,45 metres above sea level. Macao lies south of the Tropic of Cancer on the edge of tropical ocean, enjoying long summers with little evidence of winter and high levels of precipitation, giving a wet and warm climate characteristic of such granite landforms in the tropics. (3)

The name 'Macao' was not coined until the middle years of the Ming dynasty. The northern part of the peninsula was known by the name of 'Mong Ha'• ('Wangxia') which remains unforgotten today, and the southern part of the peninsula was known as Haojing, • a name which carries the smell of the sea with it. Macao peninsula was formerly also known as 'Haojing ao'• ('Haojing Bay'), 'Jinghai',• 'Jinghu',• 'Haojiang',• 'Lianyang',• 'Xiangshan ao' ('Xiangshan Bay'), 'Haijue',• all of them reflecting the produce, topography and scenery of the area. 'Taipa' was originally known as 'Tanzi'• and 'Longtou Huan',• until it was written in Portuguese as 'Taipa'. 'Coloane' was also known by the names 'Jiuao Shan'• and 'Yanzao Wan'.• Research suggests that the name 'Coloane' was originally borrowed from 'Guolu (Wan)'• (village) in Dahengqin• and was written in Portuguese as 'Coloane'. These geographical names are a product of their past. They are part of the sediment which has accumulated through history, and had been coined before the Portuguese arrived in the Territory. (4)

'Macao's earlier name 'Haojing' was written in Portuguese as 'Oquem', a transcription of the Fujianese pronunciation of 'Haojing'. This was written in English as 'Macao', which the Portuguese wrote as 'Macau', which was translated into Guangdongnese as 'Makau' ('Majiao').• Evidently these names were simplifications of the sixteenth century names 'Amagua', 'Amaguam', 'Machoam', 'Maquao', which were themselves renditions of 'Ama Gang'• and 'Mage'. • It is generally accepted that on coming ashore the Portuguese asked the name of the place they had come to, and mistakenly applied the name of the 'Mage miao'• ('Ama Temple') to the whole peninsula. (5) The 'Ama Temple'• was called 'A-macau'• ('Amage') by the Fujianese. The popular belief among Macanese people is that merchants came from Fujian• and Chaozhou• to the Ama Temple during the Chenghua• period reign of the Ming dynasty Emperor Xianzong• (r.1465-†1487). It is also held that the oldest building in the Ama Temple, the Hongrendian• (Hall of Great Benevolence), was constructed in the first year of the Hongzhi• (r.1488-†1505) period reign of the Ming dynasty. According to records, the Fujianese merchants carried out their intentions of building a temple to worship, which was feted by a grand ceremony at which incense was burned incense. On a large stone in the temple today is carved a picture of a Chinese sailing vessel with an inscription praising the Goddess Ama. This highlights the seafaring characteristic of Macao. On the 16th day of the 7th month of the Daoguang reign, year nineteen (DG 19 = 1839) in the Qing dynasty, when Lin Zexu• was appointed Supervisor of Macao, his tour of inspection included the Ama Temple and the Lianfeng miao• (Lotus Temple). In Rua dos Pescadores• (Fishermen Street) in Macao there is a second temple to the Goddess Ama, the Majiaoshi tianhou miao• (Macau Seac Temple). A study undertaken by researchers in Shenzhen• and Jiangshan• "[...] to investigate the influence of the legend of the Goddess Ama in the Hong Kong, Macao and Shenzhen area [...]" reports that within the 3.000 km² area of Hong Kong, Macao and Shenzhen (Baoan)• are found certifiable remains of sixty-six temples dedicated to the Goddess, all built during the Ming and Qing dynasties, leaving aside further temples which may have been built in the period of the Republic of China (1912-1949). Fotangmen tianhou miao• (Fotangmen Goddess Temple) in Hong Kong (built between 1225 and 1264), Chiwan tianhou miao• (Tianhou Goddess Temple) at Shekou• near Shenzhen (built between 1403 and 1424) and Macao's Mage miao (Ama Temple) (built in 1448) are the most widely known temples in Zhujiang estuary, three rivals vying for power. (6) Research has found that the earliest references to Ama, belief in the Goddess Ama and the temples dedicated to her are found in Meizhou,• in Putian• county, Fujian. She was originally a sorceress from Meizhou• Island. The wife of a man named Lin, she was known as Lin Mo• or Lin Niang,• and seemingly was born on the 23rd day of the 3rd month of the first year of the Jianlong• period reign of the Bei Song• (Northern Song) Emperor Taizu• (960 AD) and passed away on the 9th day of the 9th month (of the Chinese calendar) in 987 AD. After her death she was worshipped as a goddess. (7) Today she is still known throughout the southern and south-eastern coastal areas of China, in Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan, as well as in Japan, Southeast Asia and beyond. Importance has been attached to the inscription in the Ama Temple and related historical materials, because they reveal one of the most striking symbols of China's overseas maritime trade contacts and culture from the Bei Song dynasty. It has been computed that in the site of the Ama Temple alone, no fewer than thirty stone inscriptions have survived as testimony to the nearly two centuries from the mid-Qing to the Republican period, making it the most concentrated collection of Chinese stone inscriptions in Macao. The two poems reproduced here describe the scenery of the Ama Temple in Macao. The first is a stone inscription by Zhang Daoyuan,• zhifu• (prefectural official) from Guangzhou who went to Macao in Qianlong• reign year, fifty two (GL 52 = 1788), which reads:

“遙轉蓮花島,

天然石構亭。

當軒浮積水,

護楫有仙靈。

海覺終宵碧,

榕垂萬古青,

鯨波敘砥定,

風雨任冥冥。”

("Winding through labyrinthine lanes on the lotus island,

There stands the stone pavilion, eternal like the world itself

Pictured through pavilion posts the buoyant waters flow.

The heavenly spirit protects the fishing junks As jade green sea spreads to the far horizon While nearby the ancient banyan spreads its overarching canopy.

The island, like mighty rock, withstands the crashing whale-waves

While driving wind and rain leave unperturbed its quiet dignity.")

After Zhang Daoyuan had applied his inscription to the Ama Temple, other visitors composed poems in response, such as Yang'a Jueluo• from Ximi,• whose poem reads:

“蓮峰浮遠島,

廟貌仰雲亭。

萬頃凌霄際,

千艘仗赫靈。

海流天地外,

神護潮汐青。

萬国朝宗日,

馨香極杳冥。”

("Like a faraway lotus floating in the sea, A pavilion, like a temple, looking in the clouds

The vast, vague expanse, as of a thousand acres,

The thousand ships depend upon the supernatural Spirit,

The waters flow beyond the world's perimeter

The blue-green evening tide is guarded by the Spirit

As men of many races seek solace in this place,

Fragrance fades into the evening stillness.")

Poets were filled with reverent admiration for the Goddess Ama, musing on her imposing and powerful spirit, which seagoing vessels of all kinds relied on for protection while they were under sail. Amongst these ships were those bringing tributes: " [...] from ten-thousand lands to the Imperial Court, carrying treasures as tribute." Poets thus lyricised about how "[...] men of many races seek solace in this place, fragrance fades into the evening stillness." These are bold words from a time when lyrical poetry flourished. Associate Professor Zhang Wenqin's• textual research suggests that this poetry was composed in Qianlong reign, year sixteen, yimao• (QL 16 = 1752), during which year Yang'a Jueluo from Ximi was serving as left flank garrison leader in Guangdong. (8) Zheng Wenqin also points out that besides a temple dedicated to the Goddess Ama, the Ama Temple also contains a Buddhist temple, called Zhengjue chanli• (Zhengjue Temple) or Haijue si• (Haijue Temple). Another work by Zhang Wenqin cites Zheng Weiming's• calculation that in the Ming dynasty there were eight places in Macao where the Goddess Ama could be worshipped. Besides the Goddess Ama, the people of Macao could also worship other sea spirits such as Zhuda xian• (Immortal Zhuda), Sanpo shen• (Goddess Sanpo), Hong shengwang• (Sacred Emperor Hong), Shuishang xiangu• (Water Fairy) and Longmu• (Dragon Mother) of Yuecheng• (now Yuecheng in Deqing• county). (9)

On Liangfeng shan• (Lotus Hill) - also known as Wangxia shan• (Mong Ha Hill) - in Macao today stands the Liangfeng miao• (Lotus Temple), known previously as the Tianfei miao• (Temple of the 'Heavenly Princess'), which was constructed during the Ming dynasty in Wanli• reign, year twenty (WL 20 = 1592). This is another of the temples to the Goddess Ama which were built with the support of the Fujianese. Since this temple was constructed later than the Ama Temple, it acquired the name 'Xin Ama miao'• ('New Ama Temple') when it was expanded during the Qing dynasty. This name was then shortened to simply 'Xin miao'• ('New Temple'). The name 'Liangfeng miao' ('Lotus Temple') began to be used during the Daoguang period (r.1821-†1850). Most of the spirits worshipped are seldom found at other temples in Macao. One exception is the 'Puji chanyuan'• ('Temple of All Encompassing Aid'), known popularly as the 'Guanyin tang'• ('Guanyin Temple'), located further north in Mong Ha, which was built at the end of the Ming dynasty, when Qiseng Dashan• came to Macao vowing to resist the Qing regime, and the Guanyin Temple was expanded as the Temple of All Encompassing Aid. (10)

The Ama Temple, the Temple of All Encompassing Aid and the stone inscriptions in existence now and in the past in Macao "[...] reflect the strong background of Chinese culture in Macao, richly endowed with references to Chinese history and culture [...]",as asserted by Zhang Wenqin. This evidence also proves that the Macao peninsula and the 'island' of Macao were not completely undeveloped before the arrival of the Portuguese, British and Dutch colonialists.

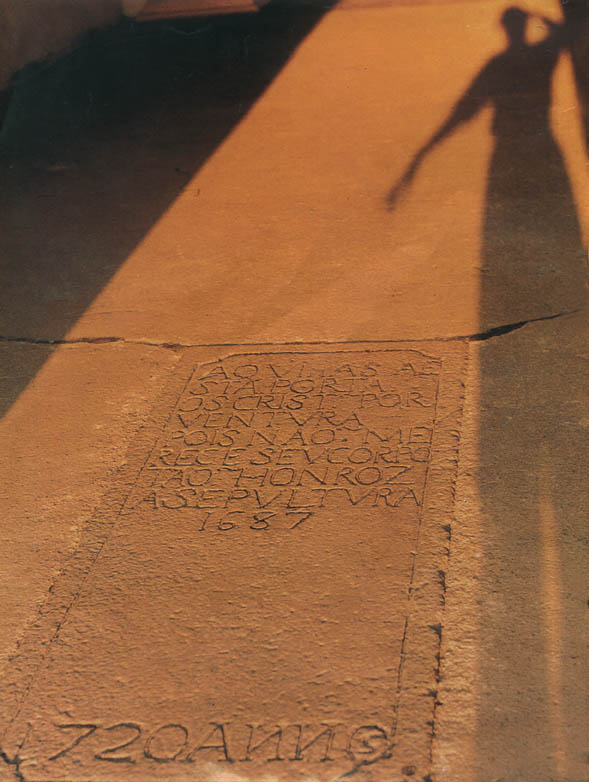

The history of Macao was such that during the Ming and Qing dynasties, the Territory came under the administrative jurisdiction of the county of Xiangshan. • According to the Yudi zhi, yange• (Territory and development) in Xiangshan xianzhi• (Xiangshan County Records) compiled by Shen Lianghan• in the Kangxi• period (r.1662-†1722), Xiangshan county was referred to -- during the Chunqiu Zhanguo• (Warring States) period (475-221BC) --"[..] beyond old Yang• [... and...] outside the boundary of Yangzhou."• During the Qin• (221-206BC) and Han• (206BC-AD220) dynasties the area was part of Panyu• county in Nanhai• prefecture. One theory holds that the area was part of Boluo• county, but the discovery in 1955 of Dong Han• (Eastern Hart) grave at a Li• and Zheng• clanhouse in Kowloon• (Jiulong) brought to light an inscription including the name "Panyu", which suggests that Hong Kong and Macao were in Panyu county during the Han dynasty. In Xianhe• reign, year six (DJ 6 = 331AD), Emperor Chengdi• of the Dong Jin• (Eastern Jin), the area was included in Dongguan• prefecture, which was divided into Baoan• and other counties (the administrative centre of both the prefecture and county were in what is now Nantou• district of Shenzhen). Macao was in Baoan county. In Yuanxi• reign, year two (YX 2= 420) of the Jin dynasty it was placed in Xinhui• prefecture, which was divided into the two counties of Fengle• and Fengping•. Later, the Xiangshan county contained the cities of Guzi• and Gongchang•; and the city of Macao was part of Gongchang city in Fengle county.

In Wendi• reign, year ten (WD 10= 590), Emperor Kaihuang,• in the Sui• dynasty, Macao was placed in Nanhai county once again. In Tan Suzong• reign, year two (TS 2= 757), Emperor Zhide, • in the Tang dynasty, Macao was in Dongwan• county, and the administrative centre was moved to Wancheng• in what is today Dongwan city,"[...] the town of Xiangshan was established in Wenshun• district." Wenshun district included Guzi, Gongchang and other towns. In Shenzong• reign, year five (SZ 5= 1982), Emperor Yuanfeng,• in the Beisong (Northern Song) dynasty, Xiangshan village was established, continuing to be part of Dongwan. In Gaozong• reign year, twenty-two (GZ 22= 1152), Emperor Shaoxing,• in the Nansong• (Southern Song) dynasty, Dongwan (the town of Xiangshan) and also coastal parts of Nanhai, Panyu and Xinhui were combined as Xiangshan county, part of the prefecture of Guangzhou. From between Jiajing• reign, thirty-two (JJ 32= 1553) and Jailing reign, year thirty-six (JJ 36= 1557), in the Ming dynasty when the Portuguese entered Macao, until Daoguang reign, year twenty-nine (DG 29=1849) in the Qing dynasty, when the Portuguese forcibly annexed Macao, Macao (going by the names Haojing, Haojing'ao• (Haojing Bay), Xiangshan'ao• (Xiangshan Bay)) came under the jurisdiction of the Chinese government.

The geographical position of Macao, commanding the strategic passage connecting the inland stretch of the Zhujiang to the maritime traffic in the South China Sea, was an important hub of communication in the movement of trade between the Chinese mainland and overseas. Called the 'provincial bay port' for Guangzhou and Hong Kong, Macao was also a major port city at the apex of the Zhujiang estuary and was renowned as the 'Bright Pearl of the East'. Over a period of six dynasties, Macao opened up shipping routes through Dongmian,• Xisha• and Nansha• islands in the South China Sea, connecting Guangzhou with many other countries, and superceding the routes used during the Xihan• (Western Han) dynasty originating from the northern harbour ports of Xuwen•, Hepu• and Rinan•. Thus historical remains were certain to be left behind, which now await further discoveries and investigation.

During the Ming dynasty in Zhengde• reign, year nine (ZD 9= 1514), a group of Portuguese merchants arrived by ship at the port of Tunmen• outside Guangzhou, where they erected a padrão (stone monument) with a carved inscription marking their 'discovery'. In Zhengde reign, year eleven (ZD 11= 1516), Portugal sent a diplomatic envoy in the name of the King Dom João III (°1502-r.1521-†1557), in the company of Fernão Peres de Andrade, who led a fleet of eight warships to Tunmen. In the ninth month of the same year they sailed into Guangzhou and asked permission to trade. In Zhengde reign, year sixteen (ZD 16= 1521), the Portuguese were pursued at Tunmen. In Jiajing reign, year one (JJ 1= 1522), a fleet of Portuguese ships once again closed in on Xicao• Bay, but were counterattacked by the Ming forces.

In Jiajing reign year, thirty-two (JJ 32=1553), the Portuguese, claiming that their ships had suffered rough seas, temporarily put in at Macao to allow the tributes, which had become wet, to dry out in the sun. They bribed the local Ming officials to submit a request to the Ming government for them to lease and reside in Macao. Between then and Jiajing reign, year thirty-six (JJ36 =1557), by which time the Portuguese had already constructed many houses in which to live, the Ming government, presented with a fait accompli eventually consented to their residing in Macao. Later, the Portuguese used Macao as an entrepôt, establishing trade routes linking Macao with Europe, Japan and the Philippines, and Macao accordingly flourished for several centuries. (11)The port of Macao was established more than three centuries earlier than Hong Kong, a fact which is intimately connected to the superior condition of its harbour at the time. (12)

§ 3. ARCHAEOLOGICAL INQUIRY AND DISCOVERIES ON THE ISLAND OF COLOANE

It is necessary to state at this juncture that the content of the following section is mostly derived from a paper by the author entitled Lüelun Aomen Heisha shiqian wenhua yu Zhujiang sanjiaozhou shiqian wenhua de miqie guanxi• (Brief Discussion on the Close Links Between the Prehistoric Culture of Hac Sa, Macao, and the Prehistoric Culture of the Zhujiang Estuary), which appeared in "Aomen jiaoyu, lishi yu wenhua lunwen ji"• ("Collected Papers on Education, History and Culture in Macao")(13)This article was written before the publication of the book Aomen Heisha• (Hac Sa, Macao), but is marred by omissions. In some cases it was impossible to avoid errors, on account of a dearth of material, an insufficient knowledge of English and because the author did not visit Macao to consult the archaeological findings there. The present paper is written since the publication of the book Aomen Heisha but does not accommodate all the wealth of information contained within it, making only occasional reference to it. Consequently, where the present paper contains contradictory information, the book Aomen Heisha should be considered authoritative. (14)

Archaeological finds on Coloane have been made over the last twenty years. In July 1972, at the invitation of the Government of Macao, a number of Hong Kong archaeologists went to Macao to carry out a preliminary archaeological survey. Ancient remains were discovered at five locations on the Island of Coloane, south of the Macao peninsula: Cheoc Van• (Zhuwan), Hac Sa Bay• (Heisha wan), Hac Sa village• (Heisha cun), Coloane Village• (Luhuan cun) and Ka Ho• Bay (Jiuao), and in May 1973 the first exploratory dig was carried out at the Hac Sa site. According to the Brief Report by W. Kelly, several sand inclusion cord impression pots were found, sand inclusion potsherds with impressions in geometric patterns and an incomplete, weathered jade ring (approximately 4,00 cm in diameter). In the southern part of the Hac Sa site were found a sharpening stone with signs of wear, a stone spinning weight, a pointed object broken into fine fragments, and course sand inclusion potsherds, soft pottery sherds with impressions in geometric patterns. In addition there were "[...] five zhu• weights [...]," possibly including sherds of Tang or Song dynasty blue glaze pottery weights and Qing dynasty copper coins. In the northern part of the Hac Sa site, besides coarse sand-tempered and stamped pottery, a two-shouldered stone adze and three ring-shaped whetstone tools. Sand-tempered and stamped potsherds were also found near Coloane village, along with a relatively large incomplete ring (approximately 7 cm in diameter, the inner bored hole approx. 4.50 cm in diameter) and a "[...] small scraping instrument of chalcedony [...] " (approx. 5 cm long, 2 cm wide). At Ka Ho Bay, coarse sand-tempered pots, stamped pottery, fishing net weights, and blue glazed potsherds. In summary, the findings described in the Brief Report may be divided into three categories. The first is a large number of potsherds from various eras and of various kinds. The second consists of bronze implements, including the Qing dynasty copper coins, the "[...] five zhu weights [...]" dating from the Han or the Six Dynasties (220-589) and early copper fishing hooks. The third category includes stone items, including fifteen axes or adzes, fragments of a pointed implement, sixty-four pounding or beating implements, thirty whetstones and cylindrical polishing implements, as well as a further twenty-two undetermined items. Carbon (C14) testing yielded four groups of data: those items which were found between 185 and 195 cm from the surface date (relative to 1950) from 4000 ± 300 years ago (here, and below,'±' indicates 'plus or minus'). Items located at a depth of between 205 and 230 cm date from 2500 ± 600 years ago; items 100 to 105 cm deep are from modern times and items 70 to 80 cm below ground date from 866 ± 194 years ago.

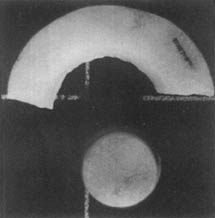

In October 1977 and June 1986, at the invitation of the Museu Luís de Camões• (Luís de Camões Museum) in Macao, the Hong Kong Archaeological Association sent Dr. S. M. Bard and his research assistant William Meacham• to lead the second dig at Hac Sa. They opened more than ten sites and trenches. (They established six plots labelled A - F in 1973, three more G - I in 1977 and four more J - M in 1985), comprising more than 150 square metres in total. The most important find was a matching quartz ring and core which were dug up together in 1977. Surrounding these objects were relics of a number of quartz cores, suggesting that this was a place where quartz rings and jewellery were manufactured. Also discovered was a complete stone ring with a concave inner edge, which looks T-shaped in the photograph. The pottery which was discovered included sand inclusion ceramic axes, the remains of the rims of jars. Decoration was in the form of cord imprinting, disjointed cord markings, curving lines, weave impressions, fine lines with raised dots. The clayware included large and small dishes with round feet, sherds of painted ring-footed dishes. Of particular interest was one such dish which could be reconstructed.

In 1985, William Meacham and the other excavators discovered another stratum of cultural remains at a depth of 1.40 to 1.80 metres in plots J and K. So the account in the Brief Report of 1985 divided the remains into upper and lower strata. The finds in the upper stratum consisted predominantly of potsherds, decoration included lines and impressed and beaten markings, winding patterns, circular patterns, fine lined patterns, there were also carved and stamped patterns. The lower level finds included a small number of fragments of stone implements and some remains of similar engraved painted ring-footed dishes. The patterns in a reddish ochre colour have evidently been painted in broad ribbons on the rims and feet of pots. Outside the belly of the pot are narrow ribbon patterns and single line patterns. Circles or elongated squares are painted as decoration on the foot of the pot outside the carved circular hole. Besides those items which appeared in the Written Report, these materials were chiefly published in the English languages editions of the 1973, 1977 and 1985 issues of the "Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan"• ("Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society"). (15)

The 1985 discoveries are worthy of further mention. Page 20 of Aomen Heisha recounts the results of the dig as follows: "The cultural artefacts in the first stratum comprised: stone implements including some with quartz core (1), a whetstone with traces of furrowed lines (1) and stone sharpening tools fashioned by chipping (2). Besides these there were thirty-six pieces of quartz or igneous rock fragments, some five-thousand or more potsherds, with various carved patterns, straw mat patterns, line patterns, woven patterns and cord patterns. Traces of a red colouring were evident on some of the white pottery. In the second stratum were mainly red clay pottery with red colouring, carving and piercing on the surface. Additionally, there were several kinds of sand inclusion pottery with cord patterning."

In 1994 and 1995 the relevant government departments in Hong Kong and Macao once again organised an investigative excavation of Hac Sa on Coloane. (Illustration 1)

Between spring and summer 1994, the Fundação Macau• (Macao Foundation) was promoting work on the cultural history of the Macao area, and actively supported an archaeological project on the early history of Macao proposed by Zheng Weiming of the Zhongwenxi• (Chinese Department) of the Universidade de Macau• (University of Macau). In July of that year, this project came into being under the auspices of a cooperative agreement between the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin• (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang zhongwen daxue• (Chinese University of Hong Kong) and scholars of the Chinese Department of the University of Macau, with the further support of the municipal government of Haidao city.

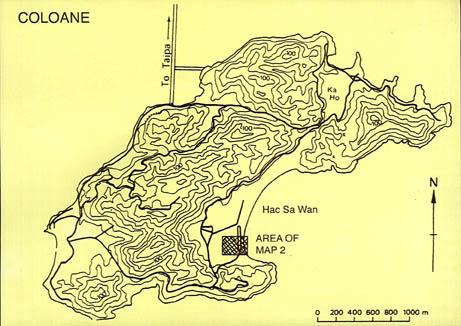

Illustration 1

The location of the archeological site at Hac Sa, on Coloane Island, Macao

(viewed from north-east south-west).

Diagram courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Illustration 1

The location of the archeological site at Hac Sa, on Coloane Island, Macao

(viewed from north-east south-west).

Diagram courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

On the 24th of August 1994, Deng Cong and Wu Weighing of the Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and Zhen Weiming of the Chinese Department of the University of Macau undertook an archaeological survey of the two islands of Taiga and Coloane. As modern buildings and development now cover much of the coast of Taipa, it was impossible to determine the layout of any ruins from the ground surface. There has also been vigorous development in recent years of the bay areas of Coloane. The survey was also hampered by large number of buildings in Cheoc Van and Ka Ho. A large hotel has been built in the north-eastern corner of Hac Sa, which has spoilt what was formerly the Hac Sa embankment. The sand dunes at the southwestern end of Hac Sa have been subsumed by Hac Sa Park, coming entirely within its perimeter. It will therefore be necessary to carry out further investigative digs to determine whether the Hac Sa archaeological plots have been destroyed by the recent construction of buildings.

Between the 2nd and the 17th of January 1994, they decided to excavate a 4 x 8 metre area, on the edge of the park's tennis courts. This area was labelled 'plot 95A'. Even though the site of this dig was only thirty-two square metres, the strata were sharply defined and some important artefacts and remains were discovered. Most significantly of all, this site proved that cultural artefacts and remains were still preserved below ground at Hac Sa. (Illustrations 2 and 3)

Illustration 2

Excavating the surface soil of the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

Photograph taken in January 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心(Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Illustration 2

Excavating the surface soil of the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

Photograph taken in January 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心(Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The significance of these discoveries was duly reported in articles in the "Aomen ribao"• ("Macao Daily News") and "Huaqiao bao"• ("Overseas Chinese News") on the 8th of February 1995. In the opinion of one of the people who made the discovery, the Macau University Chinese Department lecturer Zheng Weiming, "[...] the discovery proves that Hac Sa still contains cultural relics of considerable significance from the Neolithic period of several thousand years ago, which are truly exciting and astonishing. Hac Sa is an archaeological site which has yielded rich finds unrivalled elsewhere in the Territory of Macao, and it is hoped that in its plans for the development of Hac Sa Park the [Macao] Government will give full consideration to the importance of these archaeological remains." These comments show a full awareness of the facts of the situation, while maintaining a positive and constructive tone.

Deng Cong, • the director of the Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art of the Chinese University of Hong Kong who was presiding over the excavations said that "The discovery of these archaeological remains at Hac Sa has great significance for the study of the history of this area. One topic which currently excites the interest of international scholars is the history of interaction and spread of ethnology and culture of mankind in coastal areas three to four-thousand years ago. The remains of the stone and jade ring workshop which has been discovered at Hac Sa is similar to discoveries made in Dongnai province in south Vietnam, and Haiphong province in north Vietnam, in Chinese sites in the Zhujiang estuary such as Zhuhai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong and in other sites in Taiwan. Three to four-thousand years ago, humans from the straits of Taiwan to the southern tip of the Indian subcontinent already formed a network with distinct cultural characteristics. The discovery of Hac Sa in Macao contributes an important link to our understanding of the relationship between the cultures of the coastal areas of South East Asia and the South China Sea." The breadth of vision of this appraisal makes evident the significance of the finds at Hac Sa and indicates the direction which future research should take.

Zhang Guangzhi•, American-born Chinese and Professor in the Anthropology Department at Harvard University, recently reiterated the importance of the archaeological discovery at Hac Sa in the Preface to Aomen Heisha. He pointed out that "[...] the especial importance of Hac Sa in Macao stems from the discovery there of a jade workshop from the latter part of the Neolithic period. The jade objects made there included crystal rings, stone ring cores, unfinished blanks from which stone objects were made, stone fragments, stone carvings and so on, in addition to the tools for sculpting and shaping rings, such as whetstones and stone hammers. These are valuable materials for research into the jade craftsmanship in prehistorical southern China."

Illustration 3

The condition of plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Photograph taken in 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Illustration 3

The condition of plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Photograph taken in 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

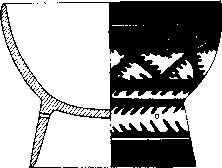

§ 4. MAJOR FINDS AND REMAINS FROM THE STRATA OF THE HAC SA SITE

Stratigraphy is one of the fundamental techniques of archaeology. It is imperative to undertake a scientific analysis of the strata of any archaeological site, especially the strata which separate different cultures, before the provenance and concomitant significance of any cultural remains or artefacts may be established. Between 1973 and 1995 four excavations were carried out at the Hac Sa site. We have no way of determining the precise relationship between the two strata from the evidence of the remains and artefacts discovered, nor of determining the chronological relationship between them, if the strata of the two digs of 1973 and 1977 are simply defined by the measured depths at which the finds were made, then we have no. The Brief Report of 1985 describes the strata of four of the plots (J, K, L and M). The first stratum is a loose layer of sand; the second is of grey sand, and is the first of the strata containing cultural remains; the third stratum is of fine grit; the fourth consists of grey sand, and is the second stratum containing cultural remains; the fifth is also of sand, but contains no cultural remains. The author of the Brief Report has divided the cultural remains into upper and lower strata. The pottery recovered from the first (upper) stratum is made up of 36% semi-refined sand inclusion light grey white pottery, 9% semi-finished fine clay, and 30% sand inclusion black-brown pottery. The jewellery, however, consisted of 62% unpatterned, plain-surfaced objects, 36% objects with cord-impression decoration, 1% with basket patterning, 0.6% with a fine knit pattern, and 0.4% with an engraved pattern. The potsherds are mottled in colour, some fine clay potsherds showing traces of a white coloured slip. (16)

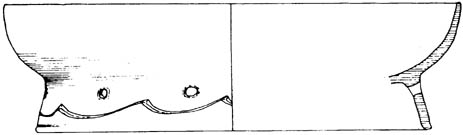

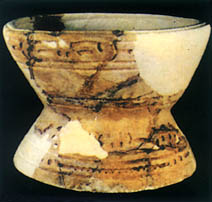

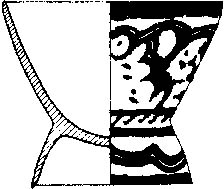

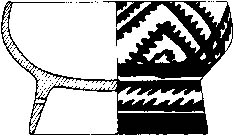

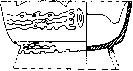

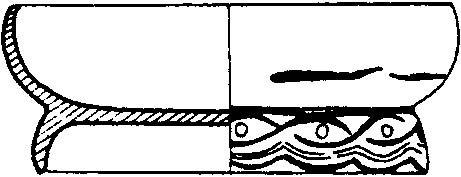

The majority of finds from the second stratum were sherds of yellow and red pottery. Those in the form of utensils included pots with cord patterns and sherds of the rims of jars, 20 to 26 cm in diameter. There were also potsherds painted deep red, with wave-shaped carved patterns and small pierced holes on the foot, with circular or square patterns painted around the holes. These were clearly identifiable as round dishes. In 1977 remains were unearthed which could be reconstructed as a low-standing dish, 21.50 cm in diameter, with a ring foot on which was engraved a wave-shaped pattern with eleven small holes pierced above. A thick stripe of red was painted where the foot joined the belly of the dish. Outside the mouth of the dish and in the belly were painted decorations which could not be clearly described because they were already eroded.

A small number of fragmented stone implements and sharpening stones were recovered from both the first and second strata. In the first stratum a number of pieces or cores from rings crafted in quartz or crystal, as well as some partly finished items and a small number of complete items which were distinctive.

Site A was excavated in January 1995. According an explanation provided for the author by Deng Cong in the presence of Wu Weihong,• and following consultation of the book Aomen Heisha, the ground may be divided into six strata. Some blue and white porcelain bowls and rims of brown glazed jars were uncovered in the lower part of the uppermost layer of topsoil, between 70 and 80 cm thick.

Illustration 4

Terracotta, stone objects and potsherds)

Unearthed from the first stratum of cultural remains of plot 95A at Hac Sa. Photograph taken in 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Illustration 4

Terracotta, stone objects and potsherds)

Unearthed from the first stratum of cultural remains of plot 95A at Hac Sa. Photograph taken in 1995 - Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學Chinese University of Hong Kong.

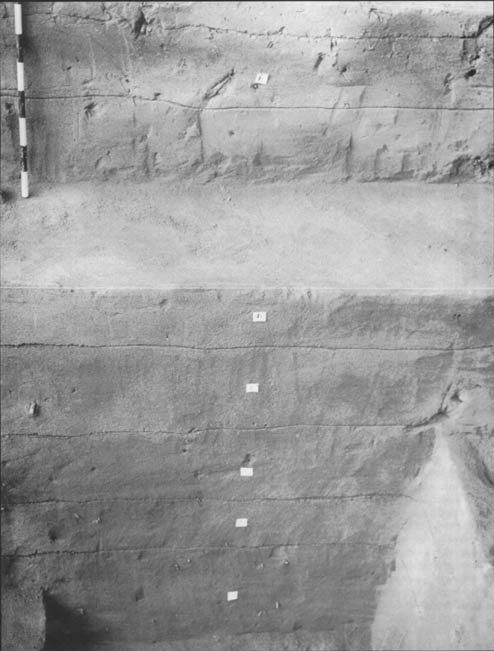

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Illustration 5

Accumulation of strata on the north wall of plot A at Hac Sa.

Photograph taken in 1995-Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

PREVIOUS PAGE:

Illustration 5

Accumulation of strata on the north wall of plot A at Hac Sa.

Photograph taken in 1995-Courtesy of Deng Cong 鄧聰 and Wu Weiyuan 吳偉源 of the Zhongguo kaogu yishu zhongxin 中國考古藝術中心 (Centre for Chinese Archaeology and Art) of the Xianggang Zhongwen Daxue 香港中文大學 Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The first stratum is 50 to 60 cm thick. Potsherds and stone implements were found in the middle part. This stratum appears to have been a relatively stable living surface. (Illustration 4)

The second stratum is 26 to 37 cm thick. No remains were discovered, making this the first intermittent stratum. The term 'intermittent stratum' refers to a stratum in an archaeological site or ruin which has accumulated naturally within a specific period of time during with no traces of human activity. Strata containing cultural remains and their contents can 'slip through the net' in an archaeological dig, if an intermittent stratum is mistakenly considered to be underlying soil and excavation does not proceed any deeper.

The third stratum is 30 to 37 cm thick. Some potsherds and scattered stone implements were found. The living surface in this stratum is somewhat thin.

No remains were discovered in the fourth stratum, making this the second intermittent stratum of the site.

The fifth stratum is more than a metre thick. A thick sand inclusion potsherd and a weathered fragments of granite were found in this stratum, considered by the excavator to have possibly been brought to the site by manual labour. This sherd is thought be older than the third stratum, because the stratum is separated from the stratum above by a very thick intermittent stratum. The paucity of finds makes it difficult to draw any conclusions. It will be possible to determine the nature of this stratum only in the light of future excavations.

The thickness of the sixth stratum is not certain. No finds were made in it. (Illustration 5)

In summary, and from a preliminary consultation of Aomen Heisha, the remains and relics discovered in plot 95 A may be listed as follows:

Remains and relics from the first stratum may be divided into two Groups A and B. The two Groups have in common terracotta and the fragmented remains of a built structure.

Group A contained a thick scattering of stone implements. Tools made of stone included stone adzes, grinding stones, sharpening stones and cylindrical polishing implements. Within the category of crafted stone ornamental objects were stone fragments, source materials for stone ornaments, half-finished objects, ring cores and stone ornaments. The author saw the following objects at an Exhibition of the Cultural History of Macao• at the Guandong shen bowuguan (Guangdong Provincial Museum) in August 1995:

(1) A complete stone adze with a long blade fashioned by grinding. The stone used is tuff. The back is slightly curved and the front surface ground down to form a slanting blade, slightly marked by use. The body of the tool has a small flaw and the surface is weathered. The object is not finished to high standard. Length 10.60 cm, width of blade 5.30 cm, weight 196g.

(2) A large stone pounding tool, also described as a stone hammer, made of hornstone. Length 1.07 cm, width 10.60 cm at widest point, thickness 7.30 cm, weight 1.85 kg. The body of the object has a shiny surface. The two ends clearly show marks made by pounding or hammering. In the middle of the two surfaces are many places where the surface is marked from being knocked against a chisel. It is not impossible that these marks were caused by the use of a stone borer. There are also three partial fragments of stone hammers.

(3) Grinding stones. Three tools for grinding stone tools, made mostly of fine red sandstone. One of the three is somewhat large and rather special. Length 14.50 cm, width 6.60 cm, 6.10 cm thick at the widest point, weight 431g. The exposed face is pentagonal in shape with several rubbing surfaces, either flat or concave. One of these surfaces has seven or eight crisscrossing grinding furrows of varying depths. This shows that the stone was used many times as a tool for working on objects of various kinds.

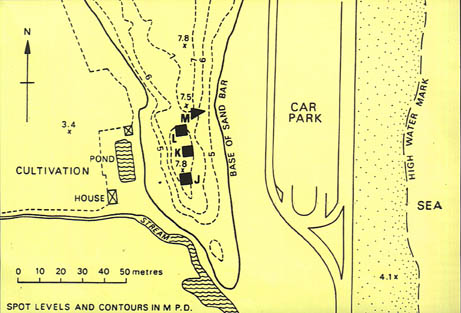

Illustration. 6

The location of the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macau-Phase III, in "Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan" “香港考古學會會刊”Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society",Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (11)1984-1985.

Illustration. 6

The location of the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macau-Phase III, in "Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan" “香港考古學會會刊”Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society",Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (11)1984-1985.

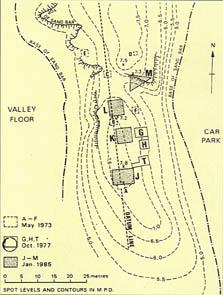

Illustration. 7

Diagram of the 1985 excavations at the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macau-Phase III, in“Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan”“ 香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (11)1984-1985.

Illustration. 7

Diagram of the 1985 excavations at the Hac Sa site, on Coloane Island.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macau-Phase III, in“Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan”“ 香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (11)1984-1985.

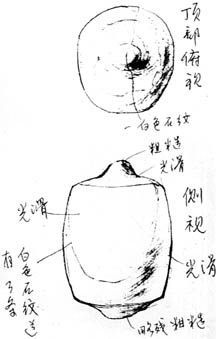

(4) Cylindrical polishing tool, also described as an inner surface tool, or by some of the Brief Report as a stone borer. Made of an opaque quartz rock, light sandy red in colour, solid and elliptical in shape like a lotus seed, with a flat, even surface, with a protruding nipple in the centre of the upper and lower ends. One is basically whole, while the other is worn almost flat. The blemishes from use may be clearly seen. A few fine curved lines caused by the stone being revolved are visible around the nipples, which are worn nearly flat. The surfaces around the nipples are shiny smooth, as if a thin layer of gum had been smeared on them. Both are 8.50 cm high, the nipples stand out about 1 cm further. The object is 5.60 cm in diameter, approximately 16.50 cm in girth. This object was also of particular interest at the time of the exhibition. The author is unfamiliar with the special shape and function of grinding tools of this kind, which are rare in Guangdong, but of which several were recovered in the upper stratum of the Hac Sa site. However, the author of Aomen Heisha, has described these objects in detail and has undertaken research on them, which is cited below. Page 59 of the book reads: "The (top) surface of this object, labelled 8a, may be interpreted as three concentric circles. [...]The innermost circle is raised in a nipple shape. The surface is pitted with blemishes from chisel blows. [...] Examination using a lens with x10 magnification reveals the presence of a large number of grains of quartz. The next circle consists of a band with a glossy surface, about 3 cm in diameter. The x10 magnifying lens reveals a large number of concentric grooves this shiny-surfaced strip. The outermost circle carries blemishes from chisel blows. The blemishes which are the furthest away are scattered unevenly. The marks in the first and third circles just described may all be the traces of some finishing technique. The shiny surface of the second circular band with was formed by the same process. The objects labelled 8c and 8a are similar, except that the protruding nipples are less pronounced, the shiny-surfaced bands are rather wider and the outermost regions have only occasional chisel blemishes. The function of this cylindrical polishing stone is a fine polishing or finishing action, quite different from the course grinding function of a whetstone (See: Zhang Hongzhao,• Shiya,• 1927, part 2.) The cylindrical polishing stone is a tool for working on the inner surface of objects. It is mostly useful for polishing the exposed inner surface of ring-shaped objects. Thus may we advance our understanding of the function of the cylindrical polishing stone.

Illustration 8

Diagram of the 1973, 1977 and 1985 excavations at the Hac Sa site, on

Coloane Island.

THE STONE RING AND JADE WORKSHOP AND REMAINS

Unearthed in the strata of cultural remains at the Hac Sa site.

Illustration 8

Diagram of the 1973, 1977 and 1985 excavations at the Hac Sa site, on

Coloane Island.

THE STONE RING AND JADE WORKSHOP AND REMAINS

Unearthed in the strata of cultural remains at the Hac Sa site.

Illustration 9.2

Traces and remains of the manufacture of rock crystal ornamental rings.

Unearthed in 1977 in the upper stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

In: MEACHAM. William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in “Xianggang kaogu xuehui Huikan”“香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7)1976-1978.

Illustration 9.2

Traces and remains of the manufacture of rock crystal ornamental rings.

Unearthed in 1977 in the upper stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

In: MEACHAM. William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in “Xianggang kaogu xuehui Huikan”“香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7)1976-1978.

Furthermore, this stratum also uncovered a number of fragments, blank items and cores of various sizes and thicknesses and remnants of various jade rings and penannular objects, all made of crystal. One example is of a ring fragment is 1.24 cm wide, 0.73 cm thick and at most 4.60 cm in diameter. Cores are the by-products in the manufacturing of rings. Three example of various sizes range from the biggest, 4.81 and 5.44 cm in diameters, 1.40 to 1.46 thick, weighing 58 to 76 g, to the smallest, 1.89 cm in diameter, 0.75 cm thick, weighing 5 g. It is evident from their shapes that the method of boring the hole entailed boring from either side and then piercing through; the size and height of the stone ring can be deduced from the thickness of the boring bit. In summary, set of objects unearthed from the Hac Sa site, comprising crystal items, stone fragments, blank, half-finished and completed artefacts, and the cylindrical stone polishing implement, all go to prove that this was formerly the location of a workshop for manufacturing stone rings." (Illustration 9)

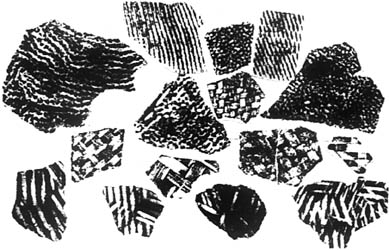

Similarly, page 54 of Aomen Heisha reads: "A total of 68 stone objects were recovered from the first stratum of the archaeological site at Hac Sa, amongst which it was possible to identify 29 distinct objects. The different types and shapes of the stone objects discovered here reflect the various manufacturing activities of prehistoric man." (Illustration 10)

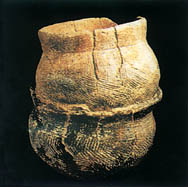

The concentration and distribution of the pottery in Group A was largely similar to that of the stone objects. The shapes which can be distinguished include three round-bottomed pots, the rim of a jar, and a number of sand inclusion cord impression potsherds. The author several examples of these in the Guangdong Provincial Museum's Exhibition of the Cultural History of Macao. (Illustration 11)

Apart from a small number of stone fragments and cores, Group B contained a high concentration of potsherds. Several fragments were located near the middle section of the northern wall of the site.

At the same time, the fragmented remains of terracotta and built structures were scattered between B4, C4 and C5 in the first stratum, running from north-east to south-west for about 1.50 metres, 14 cm wide and between 20 and 30 cm thick, the accumulations around C4 and C5 being especially highly concentrated. Five fragments of granite were found and many sand inclusion potsherds were found scattered among them. The author of Aomen Heisha surmises that this group of granite fragments are the remains of the ornamentations of the structure which survived along with the terracotta. The remains of a terracotta stove found separating Groups A and B are worthy of discussion. What was the connection between the manufacture of crystal ornaments and the remains of a terracotta stove? The author suggests that besides the normal heating function of a stove, this terracotta stove may have had some special function in the manufacture of jade objects. An illustrative example is the manufacture of crystal objects at the Nakajima• site in Higashi Imibe-chø• in Matsue• City, Shimane• prefecture, Japan, where several half-finished crystal objects were found among the remains of a stove. These were found, on comparison, to be more beautiful than the rock crystal source material from which they were made, because an internal chemical reaction in heated crystal has the effect of removing the colour. In the same way, crystal may appear more attractive if heat is applied to it.

The finds of the upper part of the third stratum and the upper part of the fifth stratum at the Hac Sa site are hereafter referred to as the lower stratum in this text. Only a small number of pot and stone fragments were found within an area of twelve square metres in the upper part of the third stratum. The distribution of the finds suggests that this stratum may also have been a living surface. Only one sand inclusion potsherd and a granite fragment were dug up within an area of 6 metres in the upper part of the third stratum. Granite pebbles do not occur in normal conditions in sand dunes. Therefore, it remains a distinct possibility that these pebbles were placed there by humans cannot be ruled out. The composition of this stratum awaits further excavation before it can be affirmed.

§ 5. SOME COMMENTS ON THE HAC SA SITE IN MACAO

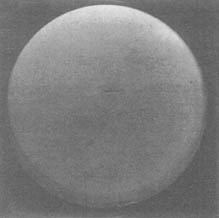

Illustration 9.3

Crystal ring and ring core.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.3

Crystal ring and ring core.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

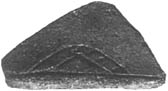

Illustration 9.4

Ring core.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.4

Ring core.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.5

Close-up of the protruding nipple on a cylindrical polishing stone (quartz rock).

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.5

Close-up of the protruding nipple on a cylindrical polishing stone (quartz rock).

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.6

Detail of one end of a cylindrical polishing stone.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.6

Detail of one end of a cylindrical polishing stone.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 9.7

Cylindrical polishing stone (original size).

Unearthed from plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Diagram by Chen Yan 陳岩of the Guangdong sheng bowuguan 廣東省博物館

(Guangdong Provincial Museum).

Handwritten annotations (clockwise from top)indicate:

Vertical view of top part / White stone lines Rough / Shiny / Side view / Shiny / Slightly rough / Three white stone lines / Shiny.

Illustration 9.7

Cylindrical polishing stone (original size).

Unearthed from plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Diagram by Chen Yan 陳岩of the Guangdong sheng bowuguan 廣東省博物館

(Guangdong Provincial Museum).

Handwritten annotations (clockwise from top)indicate:

Vertical view of top part / White stone lines Rough / Shiny / Side view / Shiny / Slightly rough / Three white stone lines / Shiny.

Although the area uncovered by the four excavation projects carried out at the archaeological site at Hac Sa on Coloane Island between 1973 and 1995 was small, approximately 174 square metres, the cultural relics and artefacts found there are important.

The significance and value of the discoveries made at the Hac Sa site lie in the fact that although these finds may be considered to have certain special characteristics when compared to some of the typical artefacts and remains which have recently come to light, in a more general context, they are, except for some minor differences, largely identical to cultural remains in similar sites from a similar period in Zhuhai, Zhongshan, Shenzhen and Hong Kong, similarly attributable to the culture of the later part of the Neolithic period in the Zhujiang estuary area. (17)

Firstly, we will consider the particular geographical characteristics and landforms of the site: Hac Sa is situated on the south-eastern side of the Island of Coloane. A geographical survey has showed that Hac Sa is unprotected coastline. The mouth of the bay is 135 degrees wide, and the beach forms a slight arc curving towards the land side, an accumlated coastline with similar features to Tonggu• Bay at Guanghai• in Taishan,• Wangfuzhou• on Xiachuan• Island and Heisha• Bay on Sanzao• Island. At either end of Hac Sa Harbour are large rocky promontories. The section of coastline is 1.2 km long, and the harbour extends 600 to 700 metres out to sea. (18) The sand embankment at Hac Sa is in three stages. The layout of the terrain was surveyed by W. Kelly in 1977 and by Dr. Zhao Zineng• in 1985. Two narrow protruding sand dunes running from north to south were still visible on an old sand embankment at the south end of Hac Sa beach. The second stage of the sand embankment is now the Hac Sa Park car park, and the third stage is the red sand-rich arenosol along the sea's edge. Excavation site 95A is situated on the third stage of the embankment. The old lagoon, now dried up, lies between Hac Sa and the slope of the hill. Hac Sa village lies on the western fringe a sloping hill and marshy ground. (19) This position means that the Hac Sa site has the geographical and environmental conditions similar to those of the sand dune sites at Qi'ao• Island in Zhuhai, Housha• Bay, Dong'ao• Bay, Caotang• Bay on Sanzao Island, Dayazhou• in the south of Dahao• Island in Hong Kong, Lung Kwu Chau• (Longguzhou), Sham Wan• (Shenwan) village on Chek Lap Kok• (Chiliejiao) Island. Archaeological discoveries and research have shown that five or six-thousand years ago, the Yue• ancestors along the strip of coastal land in the mouth of the Zhujiang would already have been able to select a harbour facing the sea sheltered from the wind, with a hill or slope behind and the running water of the lagoon to provide freshwater for drinking, and to engage in production by labour. Scores of important prehistoric sites have been discovered in Hong Kong, almost all of which are located on a rising beach, and "[...] approximately two to four metres from the water table."(20) The discoveries at the Hac Sa site also prove that it is a place which was suited for human settlement and activity.

Illustration 10.1

Stone pounding implement (stone hammer).

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.1

Stone pounding implement (stone hammer).

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

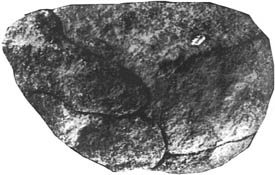

Illustration 10.2

Chipped stone implement (lamprophyre).

Length x width x height = 7.05 x 10.89 x 3.97 cm. Weight = 306.0 g.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.2

Chipped stone implement (lamprophyre).

Length x width x height = 7.05 x 10.89 x 3.97 cm. Weight = 306.0 g.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.3

Rock crystal.

Uneartyhed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.3

Rock crystal.

Uneartyhed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.4

Long-bodied stone adze.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.4

Long-bodied stone adze.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.5

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Length x width x height = 14.39 x 6.66 x 6.15 cm. Weight = 43.1 g.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.5

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Length x width x height = 14.39 x 6.66 x 6.15 cm. Weight = 43.1 g.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.6

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.6

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Unearthed from the first stratum in plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 10.7

Biscuit-shaped stone objects (ring cores?).

Middle Neolithic period.

Unearthed in 1990 from plot 3 at Longxue, Zhongshan.

Illustration 10.7

Biscuit-shaped stone objects (ring cores?).

Middle Neolithic period.

Unearthed in 1990 from plot 3 at Longxue, Zhongshan.

Secondly, as recounted above, the major contents of the Hac Sa site consist primarily of the remains of cultures from two different eras, the more important of which is the upper stratum, which will be referred to here as the 'first stratum' culture. As for the remains themselves, terracotta, scraps of charcoal, sand inclusion pots, the remains of jars and of a built structure were discovered in the first stratum in January and February 1995, proving that humans had lived there. Moreover, the remains of crystal objects, unfinished items, half-finished objects, and finished jade rings were found in the first stratum in 1977 and 1995 were discovered alongside them in the first stratum, showing that this had been a workshop where crystal and jade rings were manufactured. This evidence suggests that the people who lived in this place at that time were already capable of producing finely finished crystal or quartz ornamental rings. The renowned archaeological scholar of the Harvard University Department of Anthropology, Professor Zhang Guangzhi, wrote in the Preface to Aomen Heisha, that "[...] before today, the remains of several tens of jade workshops, dating from between the later part of the Neolithic period and the Bronze Age, have already been discovered in the coastal areas around the mouth of the Zhujiang and the eastern part of the Zhongnan• peninsula." This indicates the similar importance of the discovery at the Hac Sa site.

This stratum of cultural remains includes two large groups of stone objects and pottery. The stone objects consist mainly of fragmented large stone hammers (implements for knocking and pounding), pointed objects, chisels, (the remains of) long-bodied and two-shouldered stone adzes. Whetstones were also found, one of which has many rubbing surfaces and grooves, presumably from being used for fashioning various objects. Ornamental objects include jade and stone rings of various sizes and shapes. One rather special characteristic of the Hac Sa rings is that many of them are made of crystal. The author was not previously aware that crystal is, in a broad sense, a mineral similar to jade. Deng Cong, the author of Aomen Heisha, has used modem, scientific instruments of great accuracy to carry out an analytical survey of the source materials, half-finished materials and finished products unearthed at the Hac Sa site. He made a detailed analysis of the sequence of processes involved in the manufacture of the jade and stone rings, concluding that"[...] much can be gained from the study of ancient Chinese jade [...]" (from Zhang Guangzhi's Preface), and with reference to the work of a number of senior Chinese geologists and archaeologists, the author, as a respectful junior admirer, has been deeply inspired. He cites Zhang Hongzhao's pertinent discussion of rock crystal in Shiya, which in turn quotes from Shanhaijing:• "[...] the Tangting• mountains contain much 'shuiyu'• ('water jade') [...]." In the Jin dynasty (1115-1234), Guo Pu• noted that "[...] 'shuiyu' is crystal [...]." These sources explain that rock crystal was originally called 'water jade'. Zhang takes the word 'shuiyu' to be a broad term referring to all crystal. A literal explanation is that people at that time called rock crystal 'water jade', proving that since ancient times people have known that rock crystal was a type of jade. Modern mineralogy classifies rock crystal as a variety of phanerocrystalline quartz. Rock crystal is a transparent quartz which has crystallised completely, and has the chemical formula SiO2 (silicon dioxide). Rock crystal is a variety of jade in which the crystallisation is fine, uniform and even, or when it contains single crystals which are pure and large. The, relationship between crystal and jade is discussed in a passage they cite from the great archaeologist Jia Xianai:• "The word 'jade' is used in China today in both a broad and a narrow sense. In its broader sense, the word is still used to refer to many types of stone. In the narrow, or rather more restricted sense, the word refers to specifically to nephrite and jadeite. It is necessary to be scientific in archaeological terminology, and for this reason I have taken the word in its mineralogical sense."

PAINTED POTTERY DISHES AND POTSHERDS WITH IMPRESSED PATTERNS

Unearthed from the Hac Sa site.

Illustration 11.1

Painted ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in October 1977) from the lower stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in "Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan" “ 香港考古學會會刊 ”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7) 1976-1978.

Illustration 11.1

Painted ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in October 1977) from the lower stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in "Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan" “ 香港考古學會會刊 ”“Journal of the Hong Kong Archaeological Society”, Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7) 1976-1978.

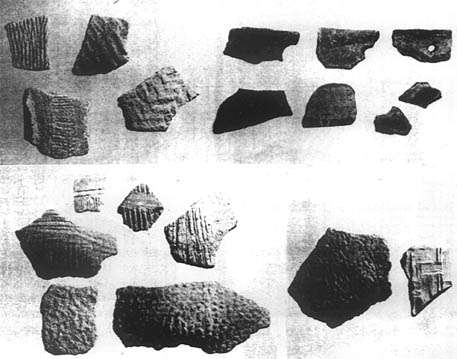

Illustration 11.3

Potsherds with impressed patterns (upper illustrations) and painted potsherds (lower illustrations).

Unearthed (in 1997) from the Hac Sa site, in Coloane Island. In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in “Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan”“香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the

Hong Kong Archaeological Society”,

Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7) 1976-1978.

Illustration 11.3

Potsherds with impressed patterns (upper illustrations) and painted potsherds (lower illustrations).

Unearthed (in 1997) from the Hac Sa site, in Coloane Island. In: MEACHAM, William, Hac Sa Wan, Macao, in “Xianggang kaogu xuehui huikan”“香港考古學會會刊”“Journal of the

Hong Kong Archaeological Society”,

Xianggang 香港 Hong Kong, (7) 1976-1978.

Illustration 11.2

Painted ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1977) from the lower stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.2

Painted ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1977) from the lower stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.4

Decorated potsherds.

Unearthed (in 1985) from the upper stratum at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.4

Decorated potsherds.

Unearthed (in 1985) from the upper stratum at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.5

Sand inclusion potsherds with cord impression pattern.

Unearthed (in 1998) from the upper stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.5

Sand inclusion potsherds with cord impression pattern.

Unearthed (in 1998) from the upper stratum of cultural remains at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.6

Sand inclusion potsherd with carved pattern.

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Unearthed from plot 95A at Hac Sa.

Illustration 11.6

Sand inclusion potsherd with carved pattern.

Whetstone with friction grooves.

Unearthed from plot 95A at Hac Sa.

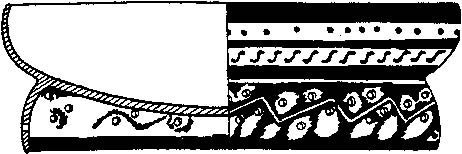

COMPARISON OF POTTERY FROM ZHONGSHAN, ZHUHAI AND HONG KONG WITH POTTERY FROM HAC SA

Illustration 12.1

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

In: Zhongshan lishi wenwu tuji《中山歴史文物圖集》 (Collected Illustrations of Cultural Relics of Zhongshan History).

Illustration 12.1

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

In: Zhongshan lishi wenwu tuji《中山歴史文物圖集》 (Collected Illustrations of Cultural Relics of Zhongshan History).

Illustration 12.2

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

Illustration 12.2

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

Illustration 12.3

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

Illustration 12.3

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed (in 1990) from Longxue site, Zhongshan.

Illustration 12.8

White pottery dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 12.8

White pottery dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 12.9

Ring-footed bowl with engraved with wave-pattern (middle Neolithic period.

Unearthed from Baishuijing site, Shiqi, Zhongshan.

Illustration 12.9

Ring-footed bowl with engraved with wave-pattern (middle Neolithic period.

Unearthed from Baishuijing site, Shiqi, Zhongshan.

However, Yang Boda•, a researcher and former Deputy Director of the Gugong bowuyuan• (Palace Museum) in Beijing, • writes the following in a section on Jade in an article on Archaeology in the Zhongguo da baike quanshu• (Great Chinese Encyclopaedia): "Jade objects may be tools, jewellery, ritual objects or furnishings fashioned from raw materials such as jadeite, nephrite, jasper, serpentine, rock crystal and chalcedony."

Evidently, Yang Boda is interpreting the term 'jade' in the broader sense here, since he includes rock crystal in the category of jade varieties.

Thus it is undoubtedly of considerable significance for us today as we attempt to classify, categorise and conduct research on objects made of jade discovered at archaeological sites that crystal (i. e., the commonly encountered crystal with a glassy shine, a oily lustre, and a warm, sleek quality) was counted as a type of ancient jade. For instance, crystal earrings found in Shixia• Culture graves in the Shixia site at Qujiang,• in the stratum of cultural remains from the Xia• (ca2000-cal600BC) and Shang• (1523-1018BC) dynasties, and a number of sizeable jade rings (and some T-shaped ornaments) which were found in the site in the sandbanks at Tangxiahuan,• in the Pingsha• district of Zhuhai included items made of crystal. In 1984 we discovered pieces of transparent purple and white amethyst in the surface soil of the Tangjiaoju• site which was excavated in Fengkai• county.

Interest has also been aroused by a complete cylindrical polishing stone found in the first stratum of plot 95A, which was appraised as quartz rock. When the exhibition was held at the Guangdong Provincial Museum in August 1995, the author thought it to be red sandstone on first inspection, but was not sure of its function. I therefore consulted Deng Cong, who said that it was in fact a tool for finishing the inner surface of jade rings which could be labelled a 'ring polishing stone', and was called an 'inner surface tool' by Japanese archaeologists. Examples have been found in the Yin• dynasty ruins at Anyang• in the north and in the Indochinese peninsula to the south. The author ascertained that two or three of these objects had been found during the 1973 excavation at Hac Sa, at which time they had been classified as stone borers. One of these had a protruding nipple at one end, but the identity of the object remained obscure. William Meacham's first article of 1975 included a sketched diagram illustrating the function of the borer. (21) It seems, then, that several of these have been discovered at Hac Sa.

Illustration 12.4

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Middle Neolithic period

Unearthed from Chung Horn Wan, Hong Kong.

Illustration 12.5

Painted dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 12.6

Painted, ring-footed dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 12.7

Painted dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 12.10

Painted dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

A Report by Qiu Licheng• of the Guangdong kaogu yanjiusuo• (Guangdong Archaeological Institute) records that in 1975 a stone borer was also found at the Baihutouling• site on the bank of the Jinjiang• in the suburbs of Enping• county in Jiangmen• district. A sketch of this item shows that it is similar in size to the one found at Hac Sa, but differs from it in that there is a protruding nipple at one end only. Judging from the stone adzes and impressed pottery which were also found, the borer dates from not later than 3000 years ago. When carrying out general-research in 1983 or 1984, the author also went to the Baihutouling site, where stone implements and pottery were found. Qiu Licheng and Deng Cong also showed that a few of these objects were also found at the Pak Mong• (Baimang) site on Lantau• Island (Dayushan) in Hong Kong, some of which similarly had a protruding nipple at one end only, and dated from the cusp of the Xia and Shang dynasties, like the Shifan• culture stone rings and cast bronzes dug up at Humen• village in Dongwan• and in the site in the sandbanks at Tangxiahuan, at Pingsha in Zhuhai. This suggests that this variety of circular whetstone was found not only at Hac Sa, but also at pre-Qin• (221-206BC) sites in Guangdong and Hong Kong. Further research is needed to establish their function, especially the methods of use. The Reports of Hac Sa have already provided detailed and enlightening research in this respect.

The pottery found in the upper stratum of the Hac Sa site consisted solely of sherds, and the quantity recovered was not great. The pottery can be divided into two categories: sand inclusion and clay pottery. Statistics reported before 1995, sand inclusion pots made up 91% of the finds, with clay pottery accounting for only 9%. The objects mostly comprised urns, cooking pots and food vessels. Of the ornamental objects, 62% were plain, 36% had cord impressions, while others had textile or basket impressions, or a raised pattern of dots made with tortoise plastron, carved decoration or small stippled circular impressions. Beaten decorative patterns, such as curved lives or straight lines, made up 2%. Those with patterns made using straw matting, with thin or thick lines, cut deeply or shallowly, prove that woven straw matting was already being used in the pottery manufacturing process. The type with the fine tortoiseshell impression raised dots are rather rare and may be considered unusual. The methods of decorating pottery found in the culture of the upper stratum at Hac Sa are not developed, as is generally characteristic of the sandbank and sand dune archaeological sites of the coastal areas in the Zhujiang estuary. There is a large proportion of sand inclusion pots which were used for cooking and a relatively much smaller number of small jars, plates, dishes and cups made of clay pottery for storing or serving food and drink. This is rather different from the shellmound and hill sites in the Zhujiang estuary of the same period. (Illustration 12)

The stone objects which were found in the lower stratum included chiselled implements and stone fragments, but no polished stone objects were found. The pottery may be divided into two categories, sand inclusion and clay pottery on the basis of different consistencies. The majority of the finds were in small pieces. A statistical analysis of two-hundred potsherds found before 1995 found that approximately 27% were sand inclusion pots, either plain or with cord impression decoration, most of which were jars or urns. Approximately 73% of the sherds were clay pottery, of which about 37% was finely finished yellow and red pottery, either plain' or with engraved patterning; 32% was finely finished yellow and red pottery with painted decoration, and a further 4% was plain white pottery. All the painted pots were rim-mouthed dishes with a ring foot which was pierced with engraved wavy patterns. A reconstructible painted ring-footed pot was found in 1977: this was an object typical of the lower stratum which carried the hallmarks of the culture of that time.

Now we will consider the culture's characteristics, qualities, age and its relationship to the prehistoric culture of the Zhujiang estuary. Firstly, it can be said that the lower stratum culture of Hac Sa is characterised by the existing plain, engraved and painted yellow and red clay pottery, a small number of white clay pots, sand inclusion pots with cord impressions and engraved patterns, and stone implements and fragments. Specifically, one part of the statistics from 1995 shows that it is characteristic that 73% of these are clay pots (32% of which is painted), but only 27% sand inclusion. Research shows that these Neolithic cultures, of which the main characteristic is the existence of painted clay pots, sand inclusion pottery with cord impression and engraved decoration (and, at certain sites, also pressed blood clam shell pattern decorations) and stone implements for whetting and polishing, are mostly the same as the cultures scattered throughout the Zhujiang estuary, Hong Kong and Macao. Archaeologically, they constitute a single cultural region, the only differences being the proportions of different types of pottery and in the varieties of the stone objects. For instance, the painted pottery, white pottery and sand inclusion pottery found at the following locations is rather different: the shellmound at Jinlan• Temple in Zengcheng• - where the author participated in excavation in September 1961 -; the sand dune at Xiantouling• in Dapeng,• Shenzhen; the sand bank at Dahuangsha• in Kuiyong;• the sand bank at Houshawan,• Zhuhai; the sand bank at Tangxiahuan in Pingsha, Zhuhai; and also at Tai Wan (Dawan), Tuen Mun• (Tunmen), Yonglang,• Chung Hom Wan• (Chongkanwan), Xiedi• Wan, Chek Lap Kok (Chiliejiao), Sham Wan (Shenwan), all in Hong Kong; the sand bank Long-xue• in Nanlang;• Zhongshan;• and Baishuijing• in Shiqi• -- where the author took part in a dig -; and Xiankezhou• in Dinghu• district of Zhaoqing;• and the Wanfuan• shellmound at Qishi,• Dongwan. The painted pottery and white pottery at Hac Sa is relatively somewhat larger than that found at Longxue, Baishuijing, Houshawan and Dahuangsha, while sand inclusion pottery of Hac Sa is somewhat taller than that found at Jinlan Temple and Wangfuan, Xiantouling and Xiankezhou. The ring-footed painted pottery dishes are the most typical and indicative of the culture excavated in this region. According to statistics produced by the author in 1995, twenty-four archaeological sites with remains from this culture have been discovered in nine cities and counties in the coastal areas and islands of the Zhujiang estuary. To those listed above can be added sites at sandbanks and sand dunes at Sham Wan (Shenwan) and Tung Kwu Chau• (Tongguzhou) on Lamma Island (Nanya), Lung Kwu Tan• (Longgutan) at Tuen Mun (Tunmen), Xiaomeisha,• Dameisha• at Shenzhen, Nanmang• Wan at Zhuhai, Dong'an• at Tangjiazhen• and Beishakeng• at Shanwei and shell mound sites at Huangcun• and Haocun• in Dongwan. (22)

DIAGRAMS COMPARING PAINTED POTTERY ITEMS FROM THE ZHUJIANG ESTUARY

Illustration 13.1

Bowl.

Unearthed from Longxue, Zhongshan.

Illustration 13.2

Dish.

Unearthed from Longxue, Zhongshan.

Illustration 13.3

Bowl.

Unearthed from Longxue, Zhongshan.

Illustration 13.4

Earthen bowl.

Unearthed in the Jinlan Temple, Zengcheng.

Illustration 13.5

Dish.

Unearthed from Xiaomeisha, Shenzhen.

In: YANG Shiting 楊式挺 Aomen Heisha shiqian wenhua yu Zhujiang sanjiaozhou shiqian wenhua de miqie guanxi 《略論澳門黑沙史前文化與珠江三角洲史前文化的密切關係》(Brief Discussion on the Close Links Between the Prehistoric Culture of Hac Sa, Macao, and the Prehistoric Culture of the Zhujiang Estuary), in "Aomen jiaoyu, lishi yu wenhua lunwen ji" 《澳門教育、歷史與文化論文集》 ("Collected Papers on Education, History and Culture in Macao"), 1995.

Illustration 13.6

Dish.

Unearthed in the Jinlan Temple, Zengcheng.

Illustration 13.7

Dish.

Unearthed in the Jinlan Temple, Zengcheng.

Illustration 13.8

Cup.

Unearthed from Chung Hom Wan, Hong Kong.

Illustration 13.9

Dish.

Unearthed from Chung Hom Wan, Hong Kong.

Illustration 13.10

Dish.

Unearthed from Chung Hom Wan, Hong Kong.

Illustration 13.11

Dish.

Unearthed from Longxue, Zhongshan.

Illustration 13.12

Dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.

Illustration 13.13

Dish.

Unearthed from Houshawan, Zhuhai.