~$S1.

Placed on the Xiangshan peninsula, at the tip of Zhujiang Sanjiaozhau Island, the almost "Island of Macao", as it was referred to in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was situated on the estuary of the Zhujiang (Pearl River) estuary and the 'mouth' of Guangdong province.

It was really a harbour town which began and expanded under the influence of the autonomous community of Portuguese and Luso-Asiatic merchants.

We know little of Macao's existence prior to it becoming as a port and remarkable trading centre between the Far East and Europe.

One can safely say that Macao, under the Chinese name of "Hou-Keng" (this guangdoguese term for "Macao" appeared in the unpublished Dicion~'ario Portugu~^es-Chin~^es (Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary) from around 1580-1588) was already a notable harbour area at the end of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth centuries.

Tom~'e Pires, in his Suma Oriental [...] (Oriental Summa [...] written in Malacca between 1512 and 1515, tells that "Oquem", a day and a night from Guangzhou by sea,"[...] is a port belonging to the Lequios [Chin.: Liuqiu; Jap.: Ryukyu] and to other nations."1

This all led to the belief that "Hou-Keng" [Chin.: Haojing] - "Macao" was a Chinese fishing village and, at the same time, had a harbour set up of some renown in maritime trade between the Chinese, Japanese and other Orientals and between the Chinese Islands and mainland, as our definition of "Small Lequio" referred to Taiwan, bread basket of Fujian province. On the other hand, the "Lequios" were intermediaries for China in the official trade set up, also carrying out intermediary trade with Japan. From around 1411, they were more notably outstanding intermediaries in Japanese trade in Southeast Asia, linking Malacca to south of Kyushu Island and Tsushima Island and also took part in Japanese external trade with China and in the flourishing trade with Southern Korea in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. 2

At the end of the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth century (1391, 1393, 1406 and 1411), there were strong trade relations between South East Asia and Southern Japan and Korea through ships from Siam presently, Thailand and presently, Java.

The presence of "Lequios" intermediaries in this external Japanese trade with Southeast Asia coincided with a Malay trade crisis (the port of Palembang, Corte, Shrivijaya), with the official Ming Chinese trade voyages and with the rise of Malacca, the central base for Chenghe's third expedition (1409-1411).

The Portuguese began to frequent this harbour area by the 1530's at the latest (1535 was the dated confirmed in the Mingshi (Annals of the Ming [Dynasty]) "[...] foreign vessels [...] without fixed anchorage [...] who came as far as Haojing [...]") and from 1557, Macao became a central trading post and in 1586 was recognised as 'Cidade do [Santo] Nome de Deus na China' ('City of the [Holy] Name of God in China').

Macao's existence grew out of a complex combination of political, economic, strategic and cultural factors. Three of these factors seemed fundamental:

1. Internal rule and the Ming dynasty's international relations during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries,

2. The trilateral Sino-Japanese-Portuguese relationship at the level of maritime trade, commerce, finance and strategic affairs, was a natural and direct consequence of the first factor and became apparent with the Guangzhou-Macao-Nagasaki route, and

3. Around the seas and coastal regions of China, the Portuguese situation in the Far East at a preliminary stage, from 1513, ended up in an autonomous Luso-Asiatic trading community and, at a cultural level, in an international Latin community (with mainly missionaries from the Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French Jesuits).

~$S2.

Each of these three factors are worthy of note, though especially the first, because it was the determining one in Macao's formation and precipitated all the other related factors, as internal conditions in China and their system of foreign relations were what made made Macao possible.

From a powerful central Government in Beijing (lit.: Northern Capital), China expressed a strong national unity based on the social ethics of the family and on global harmony with the Cosmos, and managed the differences in its vast areas and various cultures and societies, along with the tension between the Imperial Court and the peripheral states, with its strong sense of unity.

In the case of Macao, China's main concern was the friction between the mainland and the surrounding coastal regions, or rather between the national bureaucratic centre, Beijing, and Guangzhou, the regional centre of maritime trade.

During the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, China was a world manufacturing power and, at the same time, a market in need of silver and a producer of exotic and luxury goods.

With these economic forces and needs, China existed politically from 1368 under the Ming (lit.: glorious) dynasty (1368-1644) which represented a national response to the Mongolian Yuan dynasty (1279-1368).

In political terms, with direct repercussions on Macao's situation, it is interesting to point out that the Ming Emperors placed the question of internal security as the paramount regulator for international relations. This great preoccupation for the security of national Imperial power even lead the Ming dynasty to intervene more directly in economic affairs and regional problems, at-tempting to determine, or at least regulate, the flow of private sector economies (especially maritime trade at regional and international levels).

Clear indications of this pressure from the official regulating power, were the politics of the 'tax trade', the rebirth of a tax system within the framework of the external recognition of the Ming dynasty, which came about just after 1369 with Emperor Hongwu (r.1368-~+|1398) and the 'official maritime expeditions' of 1405 to 1433.

In both cases there was a power initiative from central official Government, who wanted to either discipline or substitute private, regional and local maritime trade activities. It was an attempt at controlling economic activities and organisations with purely political and administrative measures.

The politics of the tax duties limited regular maritime trade in areas which officially recognised themselves as part of the tax system of the Chunguo (lit.: Middle Kingdom). The tax officers appeared in 1369, in Korea, Japan, and Vietnam; in Cambodia and Siam in [presently Thailand] 1371; the Kingdoms on the Malay and Coromandel Peninsula between 1370 and 1390, etc.

It was once again part of the principal of political security as a regulatory factor. The Ming Government was attempting to create an official scheme of maritime and trade relations along the coast and in the China seas, hardly allowed or recognised from the official position of subordination between the States. Trade seemed to imply the recognition of Imperial Ming power, in the Far East, Southeast Asia and even certain areas around India.

The Ming's official expeditions consequently began in 1369-1370 on the Coromandel coast, and were the seven expeditions organisation by the eunuch and Moslem, Chenghe, between 1405 and 1433 during the reign of Emperor Yongle (r.1403-~+|1424). This best characterised the Ming attempt at establishing a hegemonic naval power in the Indies on behalf of the State (the same hegemonic power which they had to recognise with the tax trade).

The politics of commercial taxes and state maritime expeditions affected the private interests of the coastal Chinese, both local and regional and the overseas Chinese communities and their allies on the Islands and in the Pacific. But these efforts of monopoly or State control of a rich and powerful maritime trade activity did not succeed, and all this economic activity continued to exist and advance in ways which were not recognised as legal by the central state Government. However so-called 'pirateering' and 'black marketing' increased during the Ming period, especially along the most profitable route of the Asian-Pacific which connected China to Japan.

In 1430 or 1432, the Ming government reduced maritime trade relations with Japan to an embassy of two ships every two years. However the pressure of Sino-Japanese interests made this measure have no practical application as official sources reported seventeen Japanese commercial missions in the middle of the fifteenth century.

Nevertheless, from 1530, even if without great practical repercussions, maritime trade relations between China and Japan were officially prohibited and the Japanese were not given authorisation to send embassies to Ningbo. It is worth noting that from exactly 1530, and with greater intensity from 1542-1544, the Portuguese began to appear in Liampo Port in the vicinity of Ningbo.

From 1513, the China, with which the Portuguese were in contact, was a centre of civilisation in the Far East, a hegemonic power in this part of the world with its one-hundred million inhabitants. At the same time it was a great producer of luxury manufactured goods, attractive to any market both Eastern and Western (silks, porcelain, furniture, luxury articles, etc.), a consumer of spices and other products from Southern India and the Indian Ocean (especially through the official trade routes from Guangzhou/Guangdong) and a 'devourer' of Japanese silver.

Politically it was a State not only with a strong, interventionalist and centralised government, but also with strong regional powers. China was a dynamic social and economic region which needed an effective maritime trade in coastal areas which, however, did not threaten the essential element of centrally controlled politics and a priority for security and hegemony based on defending themselves from foreign powers.

In the sixteenth century China needed an intermediary for Southeast Asia, and even for the Indies, for nautical-maritime affairs. An intermediary who was a strong trader but at the same time weak in a political and military sense. One that had sufficient military power to secure its routes (and the Portuguese naval artillery would have this until the seventeenth century), but one that would not constitute a serious threat to Ming sovereignty.

Throughout the first half of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese would learn the rules of China's power game and, from the middle of the century, became a loved and hated intermediary.

It worked to such an extent that this intermediary ended up being made a possible partner and even privileged one, so that an Imperial Edict of 1522, which forbade contact with the "folangji" (the first official term for "the Portuguese", and a very informative one as is meant 'cannon' or 'weapon of gunpowder'), had to be applied in a very pragmatic way by the middle of the century.

Chinese sources recorded the excessive concern in the Fujian and Zhejian provinces in 1547-1549 when the authorities armed a fleet against Portuguese vessels. Protests from groups of Chinese sea traders brought about the release of some of the Portuguese prisoners taken and created a more tolerant atmosphere in the carrying out of the Imperial prohibition.

From the 1530's and 1540's, the number of Portuguese trading outposts along the Chinese coast nearer Japan coincided chronologically with an increase in silver 2 exploration in Japan (the years 1526 and 1533 saw an increase in exports for China and in the Chinese demand for silver and more notable were the years 1542 and 1543 when new mines opened).

1542-1543 were also years which marked the first Portuguese 'Japan Voyage', to the coast of Tanegashima Island, and from 1550, along the regular trade route to Japan so that in the years 1550-1552, Chinese sources already told of groups of Japanese-Portuguese traders at the markets and in the streets of Guangzhou, with the Japanese dressed 'in Portuguese style'. 3

It is evident from early on that Portuguese presence in China had a Japanese factor (in the 1530s and 1540s), which due to the increase of Japanese silver production and the Chinese market's requirements, also in the 1530's and 1540's, gave rise to the necessity and possibility of not just seasonal markets but of a permanent and organised maritime trade centre. 4 A centre which allowed regular maritime trade connections between Chinese and Japanese traders through a solution which did not upset the official politics of non-relations, but which enabled international trade, which was highly lucrative and in the interests of the producers, traders and Chinese and Japanese markets. It was not by chance that the emergence of Macao also coincided with the decrease in the activities of the Japanese Wokou pirates, who reached their greatest intensity between 1540 and 1565. Macao's port began to establish itself from 1557 and the regular route to Nagasaki dated from 1571. Japanese pirateering along the Chinese coast suffered a great reduction from 1560-1570 undoubtedly thanks to Chinese naval offensives headed by Qi Jigung, but also thanks to the new logic of Chinese-Japanese relations, created by this Portuguese international port.

The increased production of Japanese silver, and of the Chinese market for it, was a fundamental element which made it possible and necessary to have a permanent intermediary's trading out-post on the Chinese coast for this route, transporting silver, gold, copper, silk, and porcelain etc. The solution found for this trilateral maritime trade was Macao.

Why Macao and not another place in Guangdong province or other places in Fujian or Zhejiang province?

Certainly there are several reasons why "Hou-Keng" ("Macao"), with its stable weather conditions, won over other places as a permanent trading port.

From the Portuguese point of view, this natural harbour, its proximity to Malacca and the 'mouth' of Guangdong province (the first region reached by the Portuguese and the best known region with more maritime trade relations), the actual awareness of markets and possibilities, did not allow other apparently more advantageous places in the very area (like Lintin and Taishan Islands or Nantou's port) to succeed.

From the Japanese point of view, "Oquem" "Macao" was by far their preferred port in Guangdong, at Guangzhou city's gates,"[...] where everyone in the Chinese Kingdom unloads their goods [...]" (Tom~'e Pires), even though the most traditional centres, also officially not recognised for Japanese trade, where more to the north, in Ningbo, Zhejiang province.

From the Chinese point of view, "Hou-Keng" "Macao", because of its size and position, being almost an Island or Peninsula, was easily controlled in a strategic sense. Compared to the other coastal provinces of Fujian and Zhejian, Guangdong province only hoped to gain with the setting up of an intermediary centre for silver from Japan.

Haojing (Guang: Hou Keng) (lit.: Mirror of the Oyster) also seemed to be for the Portuguese maritime trade community in the China Sea largely the result of the already established situation in Asia.

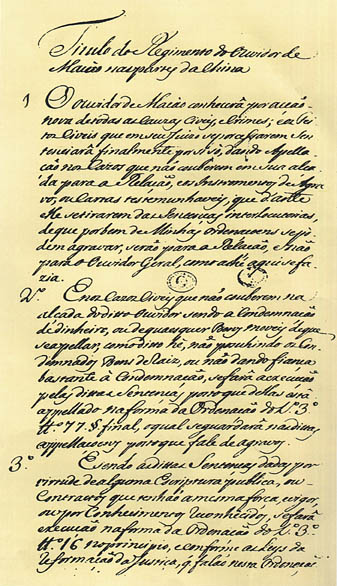

Statute of the Bylaws applicable to the rule of the Teller of Macao in the regions of China.

In: Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisboa (National Archive of Torre do Tombo, Lisbon) [ANTT].

Statute of the Bylaws applicable to the rule of the Teller of Macao in the regions of China.

In: Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisboa (National Archive of Torre do Tombo, Lisbon) [ANTT].

The other areas operating as regular trading centres which did not develop into permanent harbours, now stayed quite close to the harbour cities officially forbidden to trade with the Japanese and Portuguese, as was the case with (Xiamen) Chincheo in Fujian and Liampo (Ningbo) in Zhejian province, as in areas without a maritime trade network, like the case of (Shangchuan Dao) Sanchoh~~ao and (Lang baijiao) Lampacau, stopovers on the route between Guangdong and South-east Asia.

Before the Portuguese arrived in Haojing, there was an informal, semi-official maritime trade network which operated through the Ryukyu Archipelago as an intermediary between Southeast Asia and Japan. The new intermediaries would extend this Asiatic network, linking it to Manila and Goa as well.

The reason why Macao succeeded, faced with the failure of other attempts to establish a permanent port on Chinese shores, was undoubtedly due to this Asiatic background of an informal inter-regional network of contacts with the China seas already in existence, which the Portuguese would take advantage of to transform their port into an international harbour city.

Macao ended up achieving the status of a permanent established harbour as it had more advantages than disadvantages for the whole Sino-Portuguese consortium. Its comparative advantage was demonstrated in the maritime and trade activities by the end of the sixteenth century, and in its transformation from a seasonal trading post to a permanent one, a victory which had more to do with circumstances.

~$S3.

Let us examine the third decisive factor. Before Macao established itself as a harbour town linking the West with the Far East, there was a process of mutual learning by the Chinese and Portuguese for half a century. The first contacts were naturally ones of mutual ignorance. In Malacca in 1509, the Portuguese began to accumulate impartial information, however, Tom~'e Pires, the best informed Westerner at the time, still judged, in 1512-1515, that Afonso de Albuquerque could easily conquer "[...] all of coastal China [...]" with ten naos.

On the Chinese side, with even more limited information, in the 1520's they believed the Portuguese to be just a conquering people from Malacca and Southern India.

From 1513 at the latest, regular maritime contact between Malacca and the area of Guangdong started to include a Portuguese presence (Jorge ~'Alvares boarded a Javanese vessel in 1513 to Tam~~ao (Tunmen), the "Ilha da Veniaga" ("Island of Trade"), as shown on Portuguese maps and texts.

In 1517, the Portuguese tried to establish official diplomatic relations, as a way of integrating and establishing the network of markets in existence, (Tom~'e Pires was the first Western Ambassador in China) and at the same time, managed to become familiar with the Fujian province coastline as well.

In 1519-1520, Sim~~ao de Andrade, who commanded three junks, built a fort and placed artillery on the Island of Tunmen. He enforced justice in the Chinese territory, hanging one of his sailors, authorised buying Chinese "children" (slaves?), refused to pay taxes on his goods to the Chinese authorities and impeded other merchants from carrying out their trade when he did not manage to meet his trade objectives.

In 1522, a fleet of six ships commanded by Martim Afonso de Melo, reached Guangdongnese waters but were forced to retreat fourteen days later with the loss of two ships and dozens of men.

These years from 1519-1522 saw an attempt from official Portuguese channels in the [Portuguese] State of India, of creating a permanent commercial port, a maritime trading post, in the Guangdong area, achieving it both by treaties and military force, something akin to what existed in the East Indies. In 1522, China's central Government responded negatively and forbade contact with the 'folangji' (lit.: 'foreigners', meaning "the Portuguese" in the Imperial Edict).

Whether through diplomatic means (1517), or military (1519-1522), attempts made by the Portuguese State [of India] to create a situation of official relations did not materialise. However, semi-official and private commercial maritime relations continued to exist and to even undergo an increase from the 1530's. Both Chinese and Portuguese sources reveal the existence from 1530-1535 of regular and seasonal Portuguese trading posts along the coasts of the provinces of Guangdong (Macao/1535, Shangchuan Dao 1549, Langbaijiao 1542-1549); Fujian (Xiamen/ 1539 and 1544-1549) and Zheijian (Ningbo/1530 and with greater regularity from 1542-1544).

Centres which still continued to survive with Macao's emergence: Langbaijiao in 1560, counted on five-hundred to six-hundred Portuguese, and Portuguese trade in the Ningbo area increased at least until 1588. Yet all these seasonal trading posts would disappear as the concentration of maritime and commercial trading activity in Macao increased and this trading post would continue achieving its own dependability and security.

Macao would not only attract maritime, merchant and financial interests from southern communities in China and southern Japan, but centralise the Portuguese and Luso-Orientals' forces and potential in the China Seas.

Half way through the sixteenth century, in the 1540's and 1550's, the Portuguese were spread out over the three most powerful Chinese maritime trading provinces -- from north to south: Zhejian, Fujian and Guangdong.

From the Portuguese point of view, two factors, apart form the factors already explained; seemed to have influenced the stakes which would allow Macao to exist. From 1547 to 1549, there was systematic persecution of Portuguese vessels organised by the Fujian and Zhejian provinces' authorities. Although, as already said before, following that there was a certain moderation as the effect had already been made.

We do no know how far these persecutions were connected to the increase in the Japanese factor, but a few years later (1554) and well to the contrary of events in these provinces, the Portuguese man-aged to enjoy certain rules of maritime trade under-standing with the Guangdongnese authorities.

The Portuguese figure who achieved this understanding was the Chaul captain, Leonel de Sousa. Chaul was a port in the [Portuguese State] of India which had maintained an active trade route with China and Chinese navigators and merchants from the eleventh century.

Undoubtedly these contacts allowed to and from Chaul had a significant effect on this trade detente achieved by Leonel de Sousa, which implied a certain transformation of the Portuguese situation, as far as the image the Chinese had of them: "[...] to make this peace they changed our names from frangues, which was what they previously called us to the Portuguese from Portugal and Malacca [...]." 5

In 1554, the tendency to concentrate Portuguese maritime trade activities in the Guangdong area was already irreversible. From 1557, the gamble of giving basic stability to a seasonal settlement, in such a way as to transform it into a permanent international harbour town, began.

~$S4.

As we can see, these three factors were interdependent and, at the same time, created by the first, or in other words, by the hegemonic aspect of Chinese civilisation in the Far East, by its internal tensions (especially between the mainland Imperial centre and the maritime trading periphery) and by their external relations, above all with the second great power in the area, Japan (which had sixteen million inhabitants in the sixteenth century).

The arrival of the Portuguese as a privileged intermediary coincided with a period of European expansion throughout the rest of the world.

In the fifteenth century, the world's great technical, military and economic forces, were in the hands of the Chinese and Islamic civilisations. The fifteenth century, and especially the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, were a European challenge to the world and these ruling forces. A challenge between civilising powers still relatively balanced and not too different in organisation and technology. Equal powers especially in relationship to the East and West, where European expansion reached the sea coasts but had had little effect on the main centres.

In the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese reached the south of China and Japan, they had several technological and military advantages (their cannons and sails), but this difference was not sufficiently great enough to impose the rules of a political and economic game.

It was a decisive advantage to reach a position and a place in a foreign region, but not the power to alter circumstances, in a way to establish any type of Colonial situation or unequal exchange in the Far East.

One must be aware of the facts and above all the importance of the demographics and economics at play. In the sixteenth century Portugal had around one-and-a-half million inhabitants and would have about two million in the seventeenth century, while China had about one-hundred and fifty million and Japan twenty million inhabitants.

The Portuguese were in a process of expansion throughout the seas and coastlines of Africa, Asia and America, but Luso descendants numbered around two-hundred thousand in the sixteenth century and around four-hundred thousand in the seventeenth century. Or rather in the Far East, a few thousand, perhaps five-thousand or ten-thousand, in a region of hundreds and dozens of millions already.

The minimal technological difference, the vessels and naval artillery which were an advantage to the Portuguese were not, in the short or long term, sufficient to override or even to turn the demographic and civilising weight of the Chinese and Japanese powers.

Therefore the Portuguese were the European avant garde in the China Seas and the Indies. Avant garde in terms of nautical technology and naval technology, in terms of the power of knowledge and economic and geographical activity in the coastal regions of the world. They were a dynamic force which created the connection of East and West by sea in a regular and continuous way (the 'Cape route': 1497-1499).

Yet this difference between the Portuguese and other Europeans and Asians was minimal (especially in the China Seas), because it dealt with a difference of degrees of development and capabilities and not a difference of technological, economic and political systems.

As there was no essential difference between the Chinese, Portuguese and Japanese in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but only approximate greater or lesser states of development, or of similar cultural levels (even here the majority of instances favoured the Far East's culture and society), the Portuguese were not in a position to impose the rules of the game.

Even other Europeans involved later in the Expansion (the Dutch, British and Spanish), along with the Portuguese, were not in a position to impose standards and conditions on the Chinese or Japanese. Proof of this fact in found in the failure of every European attempt or project to conquer the trading posts on Islands or and provinces in the China Seas.

With the overall picture of power at the time between East and West, which was basically equal, the Portuguese saw themselves obliged to fit into the prevailing situation and integrate their potential and possibilities in a game whose rules they had no control over, but one which they gradually understood and respected, knowing how to gain advantages. In a picture of equal powers, but with a situation favouring the Asians, the Portuguese would continue their cultural adaption in Southeast Asia and the Far East throughout the sixteenth century. This would create interests and ways of behaving (and living) which would pave the way for a certain acceptance by the Chinese.

The Portuguese began to emerge as less strange in the eyes and interests of the Chinese and Japanese powers, and rather as 'barbarous' (this was the category of civilisation which was attributed to the Portuguese) which was also able to bring advantages and financial gains, perhaps greater advantages than the risks of staying in the China seas.

Macao's statutes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries attested precisely to the position held by the Portuguese in the Far East.

Macao was the perfect consequence of a sufficiently powerful maritime trading force to profit from the advantages and conveniences of a partnership, on the oriental side it was at the same time sufficiently weak or not strong enough, especially at a political and military level, as to be included within the undefined limits and constant conditions of the Chinese forces.

One could also say that other Europeans, at the end of the sixteenth century, were in the same situation but the Chinese did not choose them as privileged partners. However at that time in the Far East, it is important to remember that the Portuguese had two decisive 'advantages' over the Spanish, Dutch and British.

The first was the existence of contacts, knowledge and common interests from the very beginning of the century (1509-1513). The Portuguese were the first, and for some decades, the only Westerners in Oriental waters involved in trade with the Far East. The Portuguese navigators' priority was to create alliances and bases within the local situation, which became a decisive advantage when the time came for competition between Europeans in the Far East.

Another factor which was not less important and in the case of Macao absolutely fundamental, was that the Portuguese in the Far East in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were essentially Luso-Orientals.

The men and women were Luso-Indians, Luso-Malays, Luso-Japanese and Luso-Chinese, giving them competitive advantage over other Europeans due to their cultural affinity, both linguistically and physically with the Far East.

Macao's situation expressed the paradox of a Westerner sufficiently strong enough to be a desirable or undesirable associate, but insufficiently strong enough to control the other and also because of this, in Chinese logic, a partner for better or worse.

Therefore not having the outcomes of colonial pressures or of military and political force (which the Portuguese, at least from 1522, knew to be an impossible route to take), "Hou-Keng"- ("Macao"), as a harbour town for the meeting of East and West, was born out of a process of mutual trade interests between the Chinese and Portuguese (a process which we will follow in the trilogy of fundamental factors).

The harbour town of Macao evolved as a free port, an autonomous place for services, but not independent from the central and official powers and interests of China and Portugal.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in different ways and in seasonal cycles, Macao was a centre for various maritime trade routes, the main ones (which involved precious metals, gold and silver, manufactured goods beginning with silk and porcelain) being: Macao-Nagasaki, Macao-Manila, (as an addition to the galleon for American silver), Macao-Malacca (also involved with spices) and Macao-Goa (involving Malacca and Southern India).

The secondary routes were just becoming operational thanks to a river network between Guangzhou and Macao and the complementary sea networks, within a short distance along the Chinese coastline, which linked Macao and Formosa (Taiwan) and Fujian province.

This entire trade network, by river and sea, was established through communal interests and profits which could not go by unnoticed by the official central Chinese political power in Beijing.

With the opening of sea trade through Macao and Portuguese intermediaries, Imperial China's central power partially satisfied some of the manufacturing, commercial and precious metal, import and export requirements from various Chinese sectors. At the same time as having this apparent exception under control, its volume and importance always placed Macao in a position of high uncertainty for the future.

In referring to this apparent exception, Macao was the mechanism which best served the controlled and uncontrolled political opening of Imperial power during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Macao was the instrument which allowed Beijing a form of tight control over the trade economy and Chinese external relations.

The politics of official control over international maritime trade took effect with a strategy which permitted an opening and closing of the markets, undoubtedly insufficient to satisfy all the market requirements, but sufficient to satisfy the interests of powerful groups from the regional centres and the Imperial ones (Guangzhou and Beijing) putting pressure on organised illegal trade (pirateering and black market, especially between China and Japan).

So during these centuries Macao was an important instrument of Beijing's internal and external politics. At the same time, it was also of even greater value for Guangzhou and Guangdong province, who now concentrated not only on the sea routes south (a common route since the thirteenth century and having continued to exist since the eleventh century), but also the sea routes to the north and in the Pearl River estuary, until then almost monopolised by Fujian and Zhejian provinces, which were then key economic areas, even more developed than Guangdong.

This maritime trade competition between the three great coastal provinces and key economic centres in China was one of the basic patterns of Chinese life. And it is important not to forget that Portuguese intermediaries were attracted to this pattern, moving on to concentrate their maritime activities in the more northern provinces in the 1530's and 1540's and ending up by establishing themselves in Guangdong province in the 1550's.

Macao was a meeting place for business interests, competition and Chinese social and economic tensions. A fundamental exchange centre for the interplay of the deep-seated tensions between the political administrative centre (Beijing) and the coastal periphery (Guangdong) and a heavy weapon for Guangzhou in the battle for riches and development between the coastal regions of Guangdong, Fujian and Zhejian.

By the turn of the sixteenth century, Macao had the greatest maritime trade importance for the Portuguese. For officialdom in the [Portuguese] State of India, by following the 'Cape route' which linked Macao and Goa as a key maritime centre, the trip which linked Macao and Goa was the most profitable, especially for copper but also for silk, porcelain, luxury items, etc, which reached the Indian Ocean.

For the Portuguese, relations between Goa, Lisbon and Macao would also be ones of tension and conciliation of these conflicts between the political administrative powers and the trading periphery. Behind a thousand and one daily conflicts between the 'Kingdom' and the 'Macanese', there was an underlying tension between Lisbon and Goa and the autonomous periphery which sought to establish its own place and mentality for survival (Macao), between an official power and private and semi-official ones.

Throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Macao's sovereign rule demonstrated the complicated conflicts of interests and power which revolved around the maritime trading routes controlled by the international harbour town. It demonstrated the balance of power and knowledge between central and coastal China (Beijing and Guangzhou). Macao was also proof of the way the Portuguese integrated into the Chinese way of life, and its ability to serve as an intermediary (between the East and West and Japan and China), and at the same time to know how to profit and develop thanks to its network of services. It was also proof of the Chinese logic to accommodate and integrate Western change and presence through a formula of reinforcing or at least maintaining Chinese hegemony in the geographical strategy in the Far East.

Macao's situation and its sovereign rule could only be the common denominator of this multiplicity of contradictions. It had a flexible status which allowed the continuation and development of a web or multiplicity of private interests and both local, regional and semi-official powers.

Portuguese Written Reports [...] from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries noted the flow and flexibility of statute law of this autonomous place in the service of international exchange and communication in Pacific-Asia and between the West and the Far East.

Around 1582 the anonymously written Livro das Cidades e Fortalezas [...] (Book on the Cities and Forts) [...] confirmed this: "[...] notwithstanding that the land belonged to the king of China, who had his officials there who received rights which are paid for there, they are governed by the Portuguese Kingdom's laws [...]."6

Four years before being named 'Cidade do Nome de Deus na. China' ('City of the Name of God in China') by Lisbon, Macao emerged defined as a Chinese Territory under Portuguese administration. In practice the administration was shared with the Chinese (the Chinese charged taxes for example).

It is worthwhile to keep in mind that Macao's status as a Chinese Territory under joint Chinese-Portuguese rule appeared in a book written for the King Filipe II of Portugal (King Felipe III of Spain). This manuscript had a limited circulation due to the importance of the state's accounts contained inside. It was a book, which for this reason, gave true and factual accounts of the Portuguese Expansion for the Portuguese State apparatus at the end of the sixteenth century.

Today we can examine documents produced in Macao from the seventeenth century. There are also words written in manuscripts, in this instance about the local coastal power, which said in 1621: "[...] the Chinese King [sic] is the lord of the land of Macao in which we are [...]."7 This concept was reiterated in a letter, once again a manuscript, from Macao's Leal Senado (Senate/Municipal Council) in 1637: "[...] we are here in a land which is not our own nor have we conquered it, like the strongest Indian forts where we are the lords [...] but rather in a land belonging to the Chinese King where we do not have even a handful of earth, but the locality of this town, although it is our King's, it is also the Chinese King's [...]."8

In words from central Government (Lisbon) and in particular regarding autonomous power through the Carta do Leal Senado (Letter from the Senate), the situation and the Statutes of Sovereignty in Macao were characterised in a quite an objective and pragmatic way. Macao, as opposed to other harbour towns along the Asian coast, was not a Portuguese Colony. It was not the result of military conquest or of a political Treaty motivated by Portuguese powers and interests. The Leal Senado (Senate/Municipal Council) a key institution of Macao's autonomous trading power, defined this harbour town as a Portuguese city in Chinese Territory, independent from the Portuguese and built a place which "[...] belongs to the Chinese King."

At the end of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Portuguese powers, both central and local, knew very well which was the true status of Macao and documents presented bear this out. The best descriptions are found in those manuscripts which had a limited and controlled circulation, especially in cases when the real situation was economically lucrative, as was the case in Macao. One thing is manuscript statements and another thing, and sometimes the opposite, are books published at the time and which were, in certain cases, destined objectively as propaganda or a false point of view which differed greatly from the real situation.

In Macao's case, much of the confusion concerning its origins and its status of Sovereignty during the sixteenth and seventeenth century was born of the misunderstanding of the essential differences between manuscripts and printed documents, the vast difference between the Governments' accounts (central and local), objective and pragmatic out of necessity, and the ideological literary works with objectives in propaganda and the coordinated values.

The sources referred to here allow one to see Macao's Sovereign status and its situation as a practical invention of Chinese-Portuguese Sovereignty for a small peninsula of an Island off the coast of Guangdong.

I believe what was asserted before shows that this was pragmatic logic. It cannot be anything else because the Portuguese, or any other Western people, did not have the power to create such a situation and China, out of free choice, would not accept it. However it could not be anything less because the interests and profits on both sides would not have allowed it.

Therefore we are faced with a model of Sino-Portuguese shared Sovereignty. In practice it was a reduced and controlled Sovereignty divided between the local and central Chinese powers (Guangzhou and Beijing) and the Portuguese, because of the gains which the situation brought which generally took precedence over the costs and risks.

The Portuguese, especially the Luso-Asians, deserve praise. It was their reward following a pragmatic process of learning, finding points in common and of overcoming or quelling the areas of tension or possible conflict.

Thanks to the practical nature of nautical trade and to the existence of a less strict or more open border, established by the Luso-Asians, Macao could and would grow in a restricted situation. It knew how to develop itself as a meeting place for the Far East and the Western world, through a logic of interests and mutual, shared profits which promoted coexistence and in certain cases, the harmonising and overcoming of differences.

In the 1530's Macao existed more as an occasional and seasonal establishment for Portuguese trade, one among many. However, Macao managed to become a centre for an informal Chinese, Japanese and Portuguese society (in trade, naval and marine affairs). Its existence was being established and its situation created a stability and autonomy of its own which improved the partnerships within this informal society.

In this way, evolving from the practice and invention of a shared Sovereignty from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Macao turned into a special autonomous region of China, made possible thanks to the contribution of this international harbour town moulded by Portugal, the West and Latin influences.

~$S5.

Macao was a merchant marine trading entrep~^ot with diverse laws, based on a balance of interests and profits, which were always in a process of being added to and renewed. It was a place for several open partnerships, organised in conjunction with Sino-Portuguese mutual benefits, aware that"[...] the world is a ring and China is the precious stone set in it [...],"9 as said in 1630 by Fr. Paulo da Trindade, a Franciscan from Macao.

Macao's cultural activity cannot be considered without taking into account the picture of sociological roots and civilisation. Its cultural foundations were incomprehensible without understanding the city as a port, fundamentally for maritime trade with an autonomous 'filhos da terra' ('sons and daughters of the soil') community.

Macao's cultural function during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was mainly a meeting place for the differences between the world's far corners, a crossroad and learning centre as a living exposure of the Far East and the West. It was the place which introduced and quickly taught the West about the world in the Far East and the East about Latin and Christian Europe. As we have seen in the case of the first missions from Japan to Portugal and the West which, they learned the rudiments of Latin, music and Western customs in Macao (1582-1583).

As a place to exchange customs, Macao had a function as a cultural catalyser of the differences and innovations for China.

Some of these innovations, at the level of cultural behaviour of the masses, would be quickly and easily absorbed into Chinese culture, as was the case with 'corn' (taken to Guangzhou in 1516), 'nuts' the 'potatoes' 'sweet potato' 'tobacco' and 'tomatoes' for example.

At the level of everyday life, contact between people began around Macao in a multi-lingual society where it was possible to learn and teach, orally and in written form, languages which were very different from each other.

The Dicion~'ario Portugu~^es-Chin~^es (Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary), probably compiled between 1580-1588, clearly demonstrates this multilingual facet. It is basically a practical vocabulary with day to day terms about food, business and daily life. Specific terms appear in areas like medicine and astronomy, including a section which serves as an introduction to Chinese behaviour and their way of thinking.

The entries in Portuguese, words or phrases, start at "Abas" ("Coat tails") to "Zunir" ("To whiz"), followed by two columns corresponding respectively to the phonetics and the Chinese terms. There are more than two-thousand words translated in both a practical and objective way which allows not only sufficient for a basic vocabulary for a Westerner living in China, but also gives the first terms which approach a comprehensive understanding of Chinese civilisation.

We have a collective work by the Luso-Chinese Brother Tchong-Jen Nien-Kiang [Guang.] / / Sebasti~~ao Fernandes (Macao, ~&o1561-~+|1621) and the Italian Jesuits Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri. There are also the collected works of merchants and men of the land, anonymous writers who gathered together quotidian expressions and then Jesuit missionaries, who were helped by Chinese scholars, coordinated the structure and meaning of this collection.

The collected work is anonymous, edited by famous Jesuits, written in different hands and grouping together Latin and Chinese into the same cultural universe.

However, through the phonetics of the Chinese characters, this Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary reveals another of Macao's cultural functions for the city had undoubtedly become influenced by inheriting a great deal from being a meeting point for Chinese from different areas and communities. For this reason, the Dictionary's [...] phonetics are sometimes in Mandarin, Guangdongnese and other dialects, with special mention of the one from Fujian, Min Nau Hua (Hokkien).

Macao was a unique centre of linguistic exchange in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which made it a privileged place for translations and interpretations which allowed the Macanese to learn Guangdongnese, the common language, creating conditions for Western scholars and Jesuit missionaries to access the Chinese written language. It also allowed the Japanese, Chinese and Koreans to learn Latin (the international intellectual language of the period) and Portuguese, a liberal language for commerce and maritime diplomacy.

At this level of learning and teaching it is necessary to distinguish between the majority's practical level of interest and the scholars' minority interests. Unfortunately we have little written proof of the first instance which died out almost always with the interpreter's oral role, but which we know to have had real importance as verified by Korean and Chinese interpreters employed by the Dutch who spoke Portuguese and Spanish.

At an erudite level, the work of teaching and learning linguistics in Macao was centred around the Jesuit missionaries and groups within their college (the first dating from 1571).

Macao, as an autonomous city of traders, in practice enjoyed an agreement of monopoly of erudite and theoretic culture with the missionaries, or rather the Society of Jesus. Therefore, as a harbour town with a role within cultural and practical activities, it also evolved as an important intercultural centre at the level of erudite indoctrination.

Undoubtedly what is presented here is the domination of cultural activity at a clerical and religious level which performed intellectual functions which had existed in other towns long before, or even completely at the level of the layman (as was the case with medicine and printing for example).

What is interesting to understand though was that the only intellectual ~'elite organised in that period who had the conditions to respond to the challenge which Macao also presented was undoubtedly the Catholic mission and more specifically the Society of Jesus. In terms of erudite culture, Macao was the creation of the Jesuits and other Catholic missions in every way.

We can see some other major examples too; in science, technology and Western philosophy which were indirectly or directly introduced into China by the Jesuits through Macao.

It was this harbour town which produced, sent and received printed material, the basic modern techniques for cannons, (which were to have an importance not always evaluated in China's history in the seventeenth century for they served to increase the Ming's military power over its land borders with the Manchu and its sea borders from the British), global cartography and the first Western mechanical clocks, Western medicine and their instruments, etc.

The Western printing press, introduced by the Jesuits, was used in Macao to publish in Latin and Portuguese. Western typography would be introduced into Japan from Macao in 1590.

Chinese, Japanese and Portuguese interests and profits, which sustained Macao's existence, can also be interpreted at a cultural level. Two of the most important books printed then bore witness to this, Fr. Duarte Sande's De Missione Legatorum Iaponen Sium ad Romanam Curiam [...] (Brief Description of China [...]) and Jo~~ao Rodrigues' Arte Breve da Lingoa Japoa [...] (A Summary of the Japanese Language) [...], which appeared in 1620. They dealt with western elementary grammar of the Japanese language and as such became the first Western dictionary of the Chinese language, with Macao as the centre for the gathering and diffusion of information.

Essentially Macao's position as a cultural and intellectual centre of translation established itself in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

In spite of being dominant, religion did not override Macao's cultural development which, by the 1570's and 1580's began to make itself apparent.

The Roteiros de Macau para o Jap~~ao (Travel Guides from Macao to Japan) dates from this time and gives instructions on the routes to follow and the seasons for travelling: "[...] who leaves Macao with the June monsoon [...]." In a similar vein, and also the result of a collective anonymous work by the community of trade merchants and navigators were the Di~'ario de Navega~'c~~ao (Navigation Diary) and the Roteiros de Instru~'c~~ao (Travel Guides' Instructions), and the Descri~'c~~ao da viagem de um piloto portugu~^es indo de Macau para o Jap~~ao [...] (Description of a Portuguese Captain's Voyage from Macao to Japan [...]).

Around 1583, or a little later, there was the anonymously written Breve Informa~'c~~ao sobre algumas coisas da ilha da China [...] (Information on China [...]) which even explains further: "[...] when coming from Macao [...]." This sailor's text, concentrating on the Macao-Guangdong coast, was accompanied by a nautical map of the area, published in Macao at the same time.

Nautical cartography appeared both in anonymous and in manuscript form in the so-called 'portolanos' from around 1580-1590, and the Mapa de Macau (Map of Macao), dated approximately 1590-1600, and the Mapa de Macau e do delta do Rio das P~'erolas (Map of Macao and the Pearl River Delta) from around 1643, etc. Routes, navigation logs, maritime information, cartography, various surveys, like the Alturas de alguns Portos da China [...] (Locations of some Chinese Ports [...]), (1600-1610), demonstrated the cultural dynamism of the secular community. Practical and objective culture based around nautical knowledge and its direct application to trade, were once again a result of Portuguese, Chinese and Japanese presence.

For example, from the 1580's, Macao was collecting and correlating concise and specific information regarding geography, cartography, nautical issues, and the Chinese language. The works, basically by anonymous writers and written collectively, were complied from the mass of information drawn from experience, orally passed on, written and gradually accumulated."[...] we do not know anything but information [...]," or rather through the oral accounts of others at some stage like the anonymous Information on China [...], which was gradually accumulated and refined information based on "[...] experience from those who travelled these routes and others around China [...]."

At the same time, one saw the translation into Portuguese and organisation of this vast body of information, notably in the geographical and cartographical terminology "[...] the Chinese call these seasonal winds tuf~~oes [typhoons] and the stronger wind stufun [...]" ('tai fun' meaning 'great wind') and this concept was the first systemised form shown in the Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary.

Classifying, translating into Latin and printing, which already showed broader objectives, like the book of the De Missione [...], Macao, 1590, also a collective work compiled and put into Latin by the Jesuit Frs. Duarte de Sande, and Alessandro Valignano, the first vision of the Western intellectual community, gave the world some information on Chinese civilisation, gathered and compiled in Macao.

The fruits of this culture were essentially those of an import export traders' nature from a maritime point of view which was an autonomous Luso-Asian micro-society which combined the basic element of making money and operating within a network of local services in the Chinese and South Asian seas.

Therefore, above all this was a 'Culture of Transition', founded on interpreters and translators who gathered, organised and spread their knowledge through the translating from Chinese or Japanese to Latin languages, and in some cases Portuguese, especially in the spreading of new concepts and religious ideas, not only for Christianising China but also for taking Confucianism and Buddhism to the West.

Macau in the late seventeenth century-[II].

In: Number One Archive, Beijing, People's Republic of China.

It was in Macao from 1579 that Michele Ruggieri (~&o1543-~+|1607) learned of the Language and letters of the Chinese (Matteo Ricci) and began the project of translating the "Xhuq-Tsi Syz-Shue" (Xunzi Xizue), the so-called Four Books of Confucius.

Ruggieri, no doubt with the help of Chinese scholars, continued this translation until 1583. It is possible that the same scholar, whose name we do not know, participated in the elaboration of the T'ien chu, the Catholic catechism in Chinese printed in Macao in 1581 or the beginning of 1582. One should also similarly date the first translation exercises by Michele Ruggieri from these years, which were already done with such confidence and knowledge that they were printed.

Following that, Michele Ruggieri continued the translation studies of the fourth volume of Confucius in China between 1583 and 1588. Upon his return to Rome, Ruggieri would publish the first part of the Daxue (Great Learning) in Latin, which was the first of the so-called Four Books of Confucius. There are hardly sixteen lines in Latin from a Chinese book, Liber Sinensium presented as "[...] a particular book on morality [...]."

This Latin translation at the beginning of the Great Learning appeared in the work of Antonio Possevino, Bibliotheca Selecta qua agitur de ratione studiorum [...], Rome, 1593, and reprinted in 1603 and 1607.

What is interesting to point out is that the first translation of the Chinese classics was printed in Rome in 1593, an edited translation of the beginning of Confucius' Great Learning a translation begun in Macao at the beginning of the 1580's as a result of conversations between Michele Ruggieri and Chinese intellectuals.

The first Western translation of Confucius came out of Macao, as was the first Confucian text printed in Europe. It was the result of the harbour town's multi-lingual character, and was probably begun in Macao between 1581 and 1582 and printed in Rome in 1593. This translation of Confucius, from Macao, was done at the same time as the preparation of thePortuguese-Chinese Dictionary. Both works show Macao as a great centre for East-West translation and interpretation in the 1580's. On the other hand, the Rome publication of 1593 became one of the first texts printed in Europe as a result of the cultural output from Macao.

In the sixteenth century, to cite the most important cases, we still have the Amsterdam edition of Jan Huygen von Linschoten's Reysgheschrift [...] on the routes from Macao and the Voyage to Japan [...] and the Navigations around the Chinese Coast [...], a work written between the years 1560-1570 and the London edition, 1599, of excerpts concerning China in the De Missione [...], by Duarte de Sande, written and printed in Macao in 1590.

The secular cultural output of the autonomous merchant community therefore emphasised a practical knowledge for immediate use, like nautical geography and maritime maps showing explicit directions for trading on a day to day basis. This was information to put into practice which also came out in the first Portuguese-Chinese Dictionary.

The daily vocabulary presented in this work, and the compiling done by the Jesuits shows the liaison between the lay and clerical cultures. This was a compromise governed by the ideal of factual, objective knowledge. Once again it was information for power and practical use, in this case just as much commercial as for missionising purposes.

The intellectual elite from the Society of Jesus produced a clerical culture which, through texts printed like The Brief Description of China [...], systemised and adapted information, spreading it all over the West, and also Japan and America through the international language of learning, Latin.

These first cultural lay works from the end of the sixteenth century showed a practical, secular culture, fundamentally from manuscripts, which produced material of high strategic interest, which appealed only to those few interested in navigation and trade in the Chinese seas around Guangdong.

This culture, based on both the lay and clerical, systematic and practically organised information, was gathered in a way to make it accessible to various Oriental and Western groups. At the same time as being a clerical culture, meaning theoretical and systematic, it was also objective, and without forgetting the value of what was collected, they organised and correlated the knowledge, placing it partly at the disposal of western intellectual communities through the texts printed in Latin and oriental texts through those printed in Chinese, like for example the case of the 'Catechism' [T'ien?] printed on woodcuts in Guangzhou or Macao. At the same time the city's intellectual ~'elite conceived of a scholarly pedagogic project, which complimented the translating and printing, involving teaching from the most elementary to university level and forming a large Western library in the East.

Lay culture or contact with a clerical cultural intelligoutsia was always in a more or less direct form, a culture of translators and intermediaries who bridged linguistic and cultural differences.

This intellectual centre was mainly an inter linguistic centre, a laboratory for languages and translations, a meeting point which gathered, expanded and transmitted information about the far corners of the world. As a vibrant centre of translation, Macao was directly responsible for some of the constructions of the Portuguese, Chinese and Japanese languages, and not only that, broadened the lexicon of human and natural discoveries.

This intercultural centre coordinated by merchants and missionaries, or rather, lays and clerics, was both practical and doctrinal and was a melting pot of very different peoples, mainly Portuguese, Chinese and Luso-Asians, "[...] the inhabitants of which are almost all Portuguese and other mixed Christians and natives of the land [...]." 10 But there were also Indians, Malays, Japanese, Koreans, and Africans. As time passed, a greater variety of Westerners arrived, mainly Latins (Spanish, Italians, French and also, because of mutual trade, the English, Dutch and even the Danes). Such a diverse community, due to being a harbour town, created the perfect stage for the exchange of different ideas, values, customs and languages, etc.

This intellectual centre was an authentic news centre for China and the West from the sixteenth century. In cultural terms, Macao was the "[...] news of China [...]" for Europe and the world and its continuous and important epistolar production was also due to this fact.

Concerning this role as a spokesman on the impact of knowledge for the West on China, there are only two instances; firtly, the Brief Description of China [...], which was also a cultural and geographical synthesis of China and Japan printed in Macao in 1590, and encapsulated in English in the Mother of God [...] (1595), based around the Azores; Secondly, a translation from Latin of Hakluyt's First Voyages [...] under the title of the Excellent Treatise of the Kingdom of China, [...] appeared in 1599.

Alfonso Sandez, in Mexico in 1587, gave the Jesuit, José de Acosta, the basis of the structure of the Chinese language during his brief stay in Macao between 1582 and 1584. The publishing of Hist~'oria Natural y Moral de Las Indias (Natural History and Morals of the Indies) by Jos~'e de Acosta, in Seville in 1590, included references to the Chinese language and culture in the fifth and sixth chapters of Volume VI.

Macao was also mentioned in books printed in Europe, in English and Spanish. It had a dual identity as a place for intercultural exchange between the Far East and the West, with the aim of collecting and adding to information concerning China.

In cultural terms, thanks to its dual character throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Macao was an outstanding stage for the convergence of East and West and through a diverse process of learning, acted with a worldly view of civilisation in mind.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce

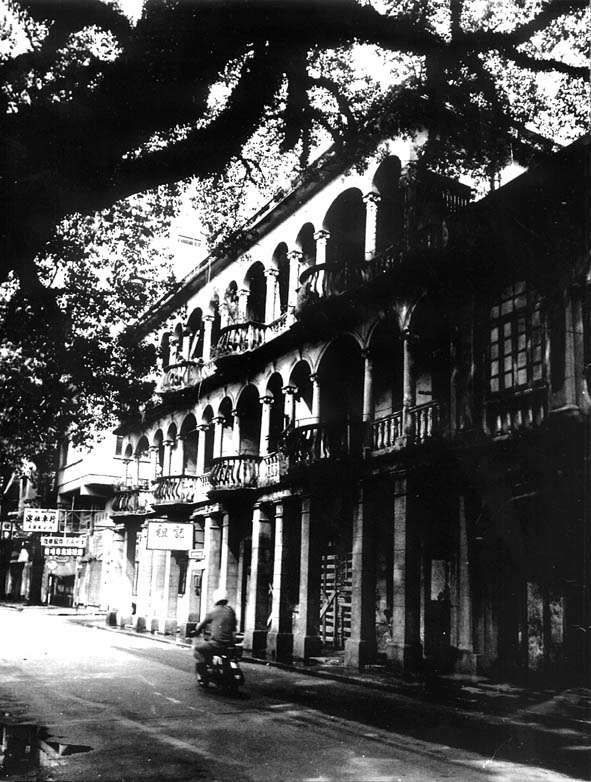

Av. do Conselheiro Ferreira do Amaral (Counselor Ferreira de Almeida Avenue).

CHAN HONG WA

Photograph. Not dated.

NOTES

ANTT: Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisboa (National Archive of Torre do Tombo), Lisbon).

BA: Bibliotaca da Ajuda, Lisboa (Library of the Royal Palace of Ajuda, Lisbon).

1 PIR~'ES, Tom~'e, CORTES~~AO, A., ed., Suma Oriental, Coimbra, Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 1978, pp.368-369 -- "[...] al~'em do porto e quamntom esta outra porto que se chama oquem he amdadura p terra de tres dias e por mar huu dia & huna noite este he o porto dos lequios he dotters nacoees [...]." ("[...] three days by land and a day and a night by sea lies another port called Oquem which belongs to the Lequios and other nations [...]."),

2 VERSCHUER, C. von, Le Commerce Ext~'erieur du Japon: Des Origines au XI~`eme Si~`ecle, Paris, Maisonneuve, 1988, especially p.101 --For information on the Japanese maritime trade network and the intermediary role of the Ryukyu Archipelago.

3 USELLIS, Robert W., As Origens de Macau, Macau, Museu Mar~'itimo de Macau, 1995, pp.24-25 -- For a transcription of the Jih-pen i-chien (A Mirror of Japan), ca 1564.

4 The still uncertain Japanese role in the 1530's, as shown by the fluctuations of its intermediary, the Ryukyu Archipelago, shifted from Malacca to Patane, in the spice trade around Southeast Asia, as reported by Vasco Calvo in 1536, in a letter written in Guangzhou. See: CALVO, Vasco, INTINO, R., ed., Informa~'c~~ao das Cousas da China, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1989, p.55.

5 FREITAS, Jord~~ao, Archivo Historico Portuguez. Jord~~ao de Freitas, Lisboa, 1910, vol. 8, p.210 -- For a letter by Leonel de Sousa to Dom Lu~'is, from Cochin, dated the 15th of January 1556.

6 LUZ, Mendes da, ed., Livro das Cidades, e Fortalezas, que a Coroa de Portugal tem nas Partes da India, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Hist~'oricos Ultramarinos, 1960, fol.75

7 BA: 49-V-5, fol.350-- Arrezoado sobre a resposta da Cidade [...], 3-2 (February) - 1621.

8 ANTT: Documentos Remetidos da ~'India (Papers from [the Portuguese State of] India), 41, fol.221 -- Carta do Senato de Macau, 24 Dezembro 1637 (24th of December 1637).

9 TRINDADE, Frei Paulo de, LOPES, F~'elix, ed., Conquista Espiritual do Oriente, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Hist~'oricos Ultramarinos, 1962, vol. 1, p.51.

10 LUZ, Mendes da, ed., op. cit., fol.75

* MA in History by the Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa [FLUL] (Faculty of Arts of the University of Lisbon), Lisbon. Ph. D. in Portuguese Culture by the FLUL. Since 1992, Assistant Lecturer at the FLUL.

During 1988-89, member of the Comiss~~ao Nacional para as Comemora~'c~~oes dos Descobrimentos Portugueses (National Commission for the Commemorations of the Portuguese Discoveries).

Author of numerous articles and publications on the history and culture of the Portuguese Discoveries. Historian and researcher of sixteenth century Macao.

start p. 63

end p.