§1. [INTRODUCTION]

The drama for Macao's people, which is more significant today, can basically be summed up in the following polemic; to be a foreigner away from their own country tomorrow and to be a foreigner within their country today. It is the dilemma of having no motherland, which has much to do with the feeling or anima of being in the midst of a dispute between two patriarchs -- the Portuguese and the Chinese. This anima resides in the feeling of belonging to an actual place or topos. Confined to a far off isolation and under remote jurisdiction, it is natural that since its 'foundation' in 1557, generations of Macanese Luso-Asians have devoted themselves to cultivating the land as a social group attached to the Motherland. However, Macao, as a place and country, was always in the shadow of attacks and danger. One cannot understand the Macanese spirit today without taking into account the mythical dimension of their collective subconscious which since the very beginning refers to the attempt to confirm and sanctify the location, the constitution of the topos. Here lies a similarity between what happens throughout history in the ever present rituals for the founding of sanctuaries, temples, palaces, cities, and empires. Clearly present in Macao's history is the configuration of a diverse system of mythology. Traces of myths or ancient sacred mysteries from different origins and traditions, along with reminiscences and perversion of the original religious teachings or epistema are also evident. Without understanding this aspect one cannot connect the more recent manifestations of the Macanese's 'spirit of place' apparent both in the way three of the most traditional authors from Macao express themselves and in the undercurrent of the 'grief of loss' or the 'grief of the end' throughout literary works produced in the last ten years. Examples are found in the settings and human comedy of Henrique de Senna Fernandes' novels or works by the talented lyrical poet, Adé dos Santos, and the mythical, visionary aspects of the urban projects by the designer and architect, Carlos Marreiros.

§2. PRECARIOUS LEGISLATION

The city of Macao seems to have had an advantage since the beginning of time with special intentions and extraordinary purposes or 'supernatural' interventions. Within these traditional concepts developed the spontaneity of the visual of the city with its invisible influences only became real through the projection of a mythical centre.

For the "Port of Macao in China" there were special factors which came together due to the need for a holy place, to project heaven onto earth, to call up the forces of good and repel the evil ones and to establish the continuity of the most distant recollections.

In the first place there was the awareness of the precarious legislation which established Macao and this was continued over the centuries. The land was not Portuguese. Map makers refer to Macao as "[...] part of China [...]".The Lord of the Land was the Emperor of China. "We are not here in our own land, conquered by us, like most of the forts in India where we are the overlords [...] but rather in the land of the King of China, where we do not have even a handful of earth [...]."(Letter from the Leal Senado (Senate), from 1637). The land has to be guaranteed by payment for the lease, always subject to negotiation and the volatile nature of the leaseholder. As a consequence there was a later diplomatic and political statute which characterised the History of Macao as having shared sovereignty. It was an unequal duel of an ever present fist of iron which flexed itself during government of Ferreira do Amaral. Yet proof of the precarious legislation, due to the intervention of such complicated and unforeseen alienating factors, were subsequently confirmed in the pax macaense, when the Pacific War, the occupation of Goa and the sequels to the Cultural Revolution saw the provocation of the exodus of 80% of Macao's traditional families in this century Over four centuries, it was probably only During the hundred years which spanned 1840-1940, that the Luso-Asian community or those of Portuguese descent in Macao enjoyed the real life of an ideal which polarised generations: the realisation of the Greek topos in the Latin locus amenus. In the past there had still been the change from one attitude to another between the possible future of economic crises which condemned the people of Macao to even more suffering, and the political swings from Beijing and the Guangdongnese Mandarins. But prior to all of this being establishment, there was the trauma of the experience of an enforced nomadic life and conflicts with the Portuguese who were forced to move commercial ports on successive occasions, Ningbo (Port.: Liampó)(1530), Aomen (Port.: Macao) (1535),Xiamen (Port.: Chinchéu) (1539) Langbai'ao (Port.: Lampacau) (1542), Shangchuan Dao (Port.: Sanchuão)(1550) and again Macao in 1553-1554. One can imagine the anxiety and search for stability felt by these private traders with regard to establishing and setting Macao from 1554, after the agreement with haidao Wang Po, made by the enemy and rival of Camões, the Captain of the Goa to Japan 'voyage', Leonel de Sousa. It was what was needed to consecrate the new area. ^^§3. AN ISLAND

In the first place there was the awareness of the precarious legislation which established Macao and this was continued over the centuries. The land was not Portuguese. Map makers refer to Macao as "[...] part of China [...]".The Lord of the Land was the Emperor of China. "We are not here in our own land, conquered by us, like most of the forts in India where we are the overlords [...] but rather in the land of the King of China, where we do not have even a handful of earth [...]."(Letter from the Leal Senado (Senate), from 1637). The land has to be guaranteed by payment for the lease, always subject to negotiation and the volatile nature of the leaseholder. As a consequence there was a later diplomatic and political statute which characterised the History of Macao as having shared sovereignty. It was an unequal duel of an ever present fist of iron which flexed itself during government of Ferreira do Amaral. Yet proof of the precarious legislation, due to the intervention of such complicated and unforeseen alienating factors, were subsequently confirmed in the pax macaense, when the Pacific War, the occupation of Goa and the sequels to the Cultural Revolution saw the provocation of the exodus of 80% of Macao's traditional families in this century Over four centuries, it was probably only During the hundred years which spanned 1840-1940, that the Luso-Asian community or those of Portuguese descent in Macao enjoyed the real life of an ideal which polarised generations: the realisation of the Greek topos in the Latin locus amenus. In the past there had still been the change from one attitude to another between the possible future of economic crises which condemned the people of Macao to even more suffering, and the political swings from Beijing and the Guangdongnese Mandarins. But prior to all of this being establishment, there was the trauma of the experience of an enforced nomadic life and conflicts with the Portuguese who were forced to move commercial ports on successive occasions, Ningbo (Port.: Liampó)(1530), Aomen (Port.: Macao) (1535),Xiamen (Port.: Chinchéu) (1539) Langbai'ao (Port.: Lampacau) (1542), Shangchuan Dao (Port.: Sanchuão)(1550) and again Macao in 1553-1554. One can imagine the anxiety and search for stability felt by these private traders with regard to establishing and setting Macao from 1554, after the agreement with haidao Wang Po, made by the enemy and rival of Camões, the Captain of the Goa to Japan 'voyage', Leonel de Sousa. It was what was needed to consecrate the new area. ^^§3. AN ISLAND ,</i> 1750.</figcaption></figure>

<p>

In this discussion, what is of greater interest is the mythological rather than the historical perspective. For this reason we have to concentrate on only three elements of the symbolism of space, which Macao)

The origins of Macao's topos can be seen to follow the rule that what makes a place sacred is its isolation (from [the italian] 'isola' meaning 'island'). Gilbert Durand said:

"Ce qui sacralise avant tout un lieu c'est sa fermeture."

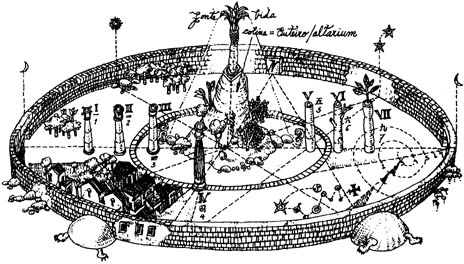

As in Biblical, and Islamic traditions, Paradise has to be a circle and isolated at the extremities -- an Island. The temptation of isolation is the temptation of pure reason. By defining a circle as a place of refuge, a divine manifestation is determined. In architecture Heidegger says that its primordial goal"[...] is to make the world visible [...]." The centre presupposes the infinity of equidistance to the circumference, therefore, it follows that the archetype of sacred locations, the pairidaeza, paradesha, paradisus, or paradise, is the sacred geometry of the square inscribed within a circle as its centre. In the designing of cities, kingdoms, sacred places and temples, which always sought to show the cosmic paradigm, the initial ritual was the outline of a circle (the mundus or the choosing or defining of an established place through a line which demarcates what is within as opposed to what is without), a border between the unmistakable tension between the sacred and profane, the kingdom of the logos and kingdom of chaos, of light and darkness outside.

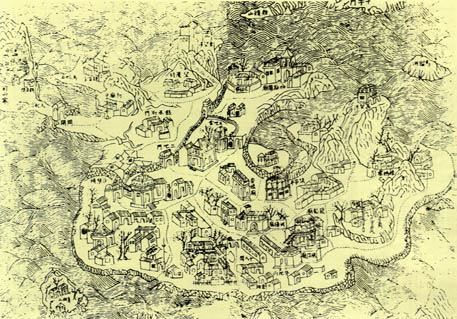

Plan of Macao. Chinese wood-cutting. In: RUAN Yuan 阮元, Guangdong tongzhi 廣東通志 (Chronicle of Guangdong Province), 1822.

All Islands are round, and ideally lend themselves to the symbol, the trajectory of the image to the concept, the constraining opposition to the chaotic element which surrounds them. An Island can represent or embody the archetype, and towns, like other microcosmos are heavenly geometrical projections and expand within the definition of infinite circles, always presupposing the reference to a central origin.

Following so much searching, it is certain that the choice of Macao as a place to 'settle' met the requirements of characteristics and practical conditions. It offered the adequate lay out of a sheltered harbour, access to supplies, and water supplies -- which were the main practical advantages seen from land.

Physically, the geography is not only that of an Island but of a peninsula, whose narrow isthmus gave the configuration of a minuscle foot stretching until the opening of the Pearl River estuary.

Yet is appears on primitive maps as "ilha de Macau" ("Macao Island") or the "quase-ilha" or "presqu'île "("almost an Island") of Macao. To our point if view, the open political intention of proposing peace with the Chinese kingdom's rulers helped the cessions made by the Guangdongnese Mandarins who, out of fear of intrusion from the folangji in the mainland, gave the authorisation for permanent trading centres to the islands on the estuary. In spite of the factors, the peninsula offered the conditions required and was "almost [an] Island".

§4. AN "ISLAND" WITHIN AN ISLAND

Opposing factors are at play when referring to an "Island" and topos. The city essentially began to present itself as an Island within an "Island". What ended up being of permanent concern was not allowing the contamination of the two opposing cultures there. As far as the Mandarins were concerned, following their first observations and experiences, foreigners were not allowed to take Chinese wives, convert others to Catholicism, venture beyond the confines of a rapidly expanding population, or to construct walls and fortifications. However, already in 1573, as a pretext to the disturbances caused by the slaves in the market gardens, the Mandarins ordered the building of the first port on the isthmus, the Custom's Harbour. Some form of separation calmed the prejudices and fears of the Chinese. The pressure from the reactionary and expansionist factors, in one way or another, which was certainly why the wall (and the harbour, interrupting the line which acerbated the tension) always existed virtually in defining, Macao and its "[...]physical continent [...]" as Aristotle would say. In the second half on the nineteenth century what materialised there was a physical, symbolic and psychological feeling of isolation with the construction of the Portas do Cerco (Border Gate), an encirclement built immediately after the taking of Passaleão and in response to the assassination of the Governor Ferreira do Amaral. Severing the connection between the continent and the adjoining territory, would culminate finally in the Macanese subconscious as a feeling of ultimately hortus conclusus. Cities always expand under the geometrical pattern of concentric circles, following the original act of creation. In the Bible, the typical topography of Eden, in Genesis, was a place surrounded by a wall. After the fall of Adam, forbidden to enter by the Angel of the Burning Spear, he remained a condemned man. Man's pilgrimage is fixed to the great circle of eschatology (the four last things: Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell): to stray from harmful innocence to harmless innocence. In order to penetrate the restricted outer boundary, and now hidden, remains the space of being unknown, unreal, the dark, chaotic stage where Man is condemned to the torture of labour, until finding a way of being reunited with God. On the margins, another evil border has a carved inscription on its door which would adapt to an inscription of Hell like in Dante. The residual miasmas of the "[...] outer darkness [...]" do not allow any possible reintegration. It is also said of cities that they will end up dying in favour of suburbs, and from suburb to suburb they are anxious about their dark peripheries. It became commonplace that the outskirts were where the dominance of the centre disappears. Oppressed like starving amoebas, towns of the industrial era had to reject the frenzy of chaotic expansion in the uncontrolled outward flow of people to the proliferies, which became satellites. But they excrete the evil areas where they purged their waste from these animals bestially consuming and proliferating. They had their convulsions in the tin can suburbs and in the rubbish dumps. In their animal analogy, they also had their embarrassing in the infera loci of dejection, excretion and degrading reproduction. The Palace and the Temple, the astral arches and the golden order of the columns all lay far away. In Macao, whereas the Chinese concern was the restraining of disturbances to peace in the Heavenly Kingdom, in the ecumenical Catholic southern Europe under Portuguese influence, the defining of walls and barriers had as their objective the demarcation of the organised space of the new polis and the institution of a 'Catholic city', an antithesis to the gentiles on the outskirts. In this way the city became an Island (in the spiritual sense) within an "Island" (geographically speaking), a microcosmos which searched for the image of the cosmos, concentrating on their sacred values. It does not concern us here to make an historical summary of the outline of the walls, to evaluate their significance and efficiency from the point of view of military defence, but moreover to examine their symbolic meaning. Broadly speaking, they were ordered to be built by Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas, immediately after the Dutch attack in 1622. The twenty previous years had been ones of panic for the Luso-Asian community in Macao, confronted with a permanent siege from the powerful Dutch naval fleet. The 1622 victory seemed to be more a 'miracle' rather than the result of normal superiority. Also, most of the forts and defences were built or fortified during this period. For the most part these defences were protection against attacks from the nearby seas. Prevention was centred on attacks from the west, as shown in the Forte de Mong-Há (Fort of Mong-Há), later replaced by the Fortaleza de Dona Maria II (Fortress of Dona Maria II), and explains itself through the actual conditions prior to the taking of the Passaleão, in Chinese territory, by Vicente Nicolau de Mesquita. At the very least it was the purely functional, efficient military strategy of having the walls placed towards the isthmus that was subject to controversy. The 'establishment' was probably 'in agreement' and on some occasions Macao was threatened from the outside with more deadly 'sieges' like cutting the water and food supplies. Independent from the background of Chinese recurring pressures and orders for demolishing this wall - which was carried out without consequence around the perimeter and the main part of the township - it is interesting here to point out a similar period when the walls signified the body of the Catholic civis, to retain its function as a magical, sacred border. We quote Mircea Eliade, when he refers to other rituals of making a place sacred: “The same thing happens with the city walls: before becoming military defences, they are magic defences, as they enclose, in the midst of a chaotic space, populated by demons, an organised 'cosmology' which means a 'centre'. This explains why during a critical period, around the time of the epidemic; the whole population gathered in a procession around the city walls, thereby reinforcing its character of providing limits and religious and magical protection." What is exposed in these critical situations is a profound symbolism, like the symbol of the Christian temple. A wall also contains a microcosmos, a living community of souls, gathered in a centre which incorporates the wall's circles. What is always present in Macao, and something which concerns up here, is that this boundary or virtual wall is always subject to realignments. In the seventeenth century, the wall had two main gateways, Santo António (St. Anthony's Gate) and Campo (Campo Gate). Through them day to day contact with the 'other side' was made, the outside exclusus space separate from the Fujianese nucleus of market gardeners, intermediaries for supplies and those people who provided services. On the great esplanade on the field near Campo Gate (Tap Séac today), "outside the walls", the lepers were exiled. The Igreja de São Lázaro (St. Lazarus' Church) was chosen for giving spiritual help to the lepers and some Chinese converts. We can imagine that a scene of O Pátio dos Milagres (The Patio of Miracles) would not develop here in the wasteland where the civilised suburb ostracised its diseased, rejected people. Always growing and in an almost geometrical progression in relation to the Luso-Asiatic community, the Chinese community soon established internal walls, multiplying and brewing an activism which was their very own. The gateways and boundaries were falling apart and became more imaginary than physical now, though even stronger mentally. They can still be detected today by carefully looking at those who have stayed some time in Macao. At the beginning of this century, the great creator of scenes from Macao's past is the writer Henrique Senna Fernandes, who shows us the impenetrable rigidity of the 'wall' which separated the Catholic town from the Chinese in his novels.

Opposing factors are at play when referring to an "Island" and topos. The city essentially began to present itself as an Island within an "Island". What ended up being of permanent concern was not allowing the contamination of the two opposing cultures there. As far as the Mandarins were concerned, following their first observations and experiences, foreigners were not allowed to take Chinese wives, convert others to Catholicism, venture beyond the confines of a rapidly expanding population, or to construct walls and fortifications. However, already in 1573, as a pretext to the disturbances caused by the slaves in the market gardens, the Mandarins ordered the building of the first port on the isthmus, the Custom's Harbour. Some form of separation calmed the prejudices and fears of the Chinese. The pressure from the reactionary and expansionist factors, in one way or another, which was certainly why the wall (and the harbour, interrupting the line which acerbated the tension) always existed virtually in defining, Macao and its "[...]physical continent [...]" as Aristotle would say. In the second half on the nineteenth century what materialised there was a physical, symbolic and psychological feeling of isolation with the construction of the Portas do Cerco (Border Gate), an encirclement built immediately after the taking of Passaleão and in response to the assassination of the Governor Ferreira do Amaral. Severing the connection between the continent and the adjoining territory, would culminate finally in the Macanese subconscious as a feeling of ultimately hortus conclusus. Cities always expand under the geometrical pattern of concentric circles, following the original act of creation. In the Bible, the typical topography of Eden, in Genesis, was a place surrounded by a wall. After the fall of Adam, forbidden to enter by the Angel of the Burning Spear, he remained a condemned man. Man's pilgrimage is fixed to the great circle of eschatology (the four last things: Death, Judgment, Heaven and Hell): to stray from harmful innocence to harmless innocence. In order to penetrate the restricted outer boundary, and now hidden, remains the space of being unknown, unreal, the dark, chaotic stage where Man is condemned to the torture of labour, until finding a way of being reunited with God. On the margins, another evil border has a carved inscription on its door which would adapt to an inscription of Hell like in Dante. The residual miasmas of the "[...] outer darkness [...]" do not allow any possible reintegration. It is also said of cities that they will end up dying in favour of suburbs, and from suburb to suburb they are anxious about their dark peripheries. It became commonplace that the outskirts were where the dominance of the centre disappears. Oppressed like starving amoebas, towns of the industrial era had to reject the frenzy of chaotic expansion in the uncontrolled outward flow of people to the proliferies, which became satellites. But they excrete the evil areas where they purged their waste from these animals bestially consuming and proliferating. They had their convulsions in the tin can suburbs and in the rubbish dumps. In their animal analogy, they also had their embarrassing in the infera loci of dejection, excretion and degrading reproduction. The Palace and the Temple, the astral arches and the golden order of the columns all lay far away. In Macao, whereas the Chinese concern was the restraining of disturbances to peace in the Heavenly Kingdom, in the ecumenical Catholic southern Europe under Portuguese influence, the defining of walls and barriers had as their objective the demarcation of the organised space of the new polis and the institution of a 'Catholic city', an antithesis to the gentiles on the outskirts. In this way the city became an Island (in the spiritual sense) within an "Island" (geographically speaking), a microcosmos which searched for the image of the cosmos, concentrating on their sacred values. It does not concern us here to make an historical summary of the outline of the walls, to evaluate their significance and efficiency from the point of view of military defence, but moreover to examine their symbolic meaning. Broadly speaking, they were ordered to be built by Dom Francisco de Mascarenhas, immediately after the Dutch attack in 1622. The twenty previous years had been ones of panic for the Luso-Asian community in Macao, confronted with a permanent siege from the powerful Dutch naval fleet. The 1622 victory seemed to be more a 'miracle' rather than the result of normal superiority. Also, most of the forts and defences were built or fortified during this period. For the most part these defences were protection against attacks from the nearby seas. Prevention was centred on attacks from the west, as shown in the Forte de Mong-Há (Fort of Mong-Há), later replaced by the Fortaleza de Dona Maria II (Fortress of Dona Maria II), and explains itself through the actual conditions prior to the taking of the Passaleão, in Chinese territory, by Vicente Nicolau de Mesquita. At the very least it was the purely functional, efficient military strategy of having the walls placed towards the isthmus that was subject to controversy. The 'establishment' was probably 'in agreement' and on some occasions Macao was threatened from the outside with more deadly 'sieges' like cutting the water and food supplies. Independent from the background of Chinese recurring pressures and orders for demolishing this wall - which was carried out without consequence around the perimeter and the main part of the township - it is interesting here to point out a similar period when the walls signified the body of the Catholic civis, to retain its function as a magical, sacred border. We quote Mircea Eliade, when he refers to other rituals of making a place sacred: “The same thing happens with the city walls: before becoming military defences, they are magic defences, as they enclose, in the midst of a chaotic space, populated by demons, an organised 'cosmology' which means a 'centre'. This explains why during a critical period, around the time of the epidemic; the whole population gathered in a procession around the city walls, thereby reinforcing its character of providing limits and religious and magical protection." What is exposed in these critical situations is a profound symbolism, like the symbol of the Christian temple. A wall also contains a microcosmos, a living community of souls, gathered in a centre which incorporates the wall's circles. What is always present in Macao, and something which concerns up here, is that this boundary or virtual wall is always subject to realignments. In the seventeenth century, the wall had two main gateways, Santo António (St. Anthony's Gate) and Campo (Campo Gate). Through them day to day contact with the 'other side' was made, the outside exclusus space separate from the Fujianese nucleus of market gardeners, intermediaries for supplies and those people who provided services. On the great esplanade on the field near Campo Gate (Tap Séac today), "outside the walls", the lepers were exiled. The Igreja de São Lázaro (St. Lazarus' Church) was chosen for giving spiritual help to the lepers and some Chinese converts. We can imagine that a scene of O Pátio dos Milagres (The Patio of Miracles) would not develop here in the wasteland where the civilised suburb ostracised its diseased, rejected people. Always growing and in an almost geometrical progression in relation to the Luso-Asiatic community, the Chinese community soon established internal walls, multiplying and brewing an activism which was their very own. The gateways and boundaries were falling apart and became more imaginary than physical now, though even stronger mentally. They can still be detected today by carefully looking at those who have stayed some time in Macao. At the beginning of this century, the great creator of scenes from Macao's past is the writer Henrique Senna Fernandes, who shows us the impenetrable rigidity of the 'wall' which separated the Catholic town from the Chinese in his novels.  </i>which took place at the Instituto de Investigação Científica e Tropical (Instituto Institute of Tropical Scientific Investigation) at the Museu Nacional de Etnologia (National Museum of Ethnology) in 1991.

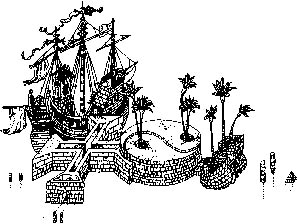

Not having been supplied with further information and more rigorous material on the sources of this illustration, we will not risk an in depth definitive analysis of this very curious and interesting document. This view of Macao which gives a description of daily life in the style of Brueghel is evidently based on a previous one, attributed undoubtedly to Theodore de Bry (°1527-†1598) compiled presumably in 1598, the year of the author) Petits Voyages (Short Travels) which was published by his family after is death in Frankfurt am Main in 1607 (Latin edition). Simplified and relieved of most of its background details, this engraving -possibly a revised production by De Bry - was crowned with the Latin inscription "Non ex quovis ligno fit Mercurius", and at the bottom left, a foreground composition of a tamer forcing a donkey to go through a hoop. In order to hazard a more precise interpretation we would need to know if this engraving was originally accompanied by other plates and/or from which collection or published work, also the order and under which titles, etc. In the meantime, however, we limit ourselves to examining some information from its writings and symbolic compositions. The mentioned Latin quotation, familiar in the enclosed realm of followers of the 'Great Art', or Alchemy, became common idiomatic use with a similar meaning: "It was not from this foul matter that Mercury was extracted". It is known that Mercury, like Sulphur and Salt were the three components of the material prima (primal matter) of the 'Supreme Art', being the basic of Hermetic Philosophy and the affirmation of the unity of matter. These elements did not specifically define the respective chemical substances, but referred to certain qualities of matter. Sulphur defined the active qualities (the forma, the masculine, the active principle) and Mercury the passive properties (the materia, feminine, the passive principle), and Salt, the third element, was their binding force, like the vital spirit that unites body and soul, or the movement thanks to which the active element leaves its mark upon the passive element of all types of forms. With some exceptions, the donkey always arose in all traditions as a symbol of Darkness, the Satanic and Inferior tendencies. Alchemists saw the donkey the three-headed devil (representing Mercury, Sulphur and Salt), or rather the three main substances of Nature, the embodiment of being obstinate. In the allegorical engraving, the tamer of matter, the initiated master (with a staff and the feathers of the illuminato bedecking his forehead), compels the donkey to go through the circular hoop like a circus animal, thus operating the symbolic transformation of matter, thereby beginning the works of the 'Great Task', with vestiges of utopia in the remote view of Macao, the sole Catholic establishment in the vast expanse of China, the Porto do Nome de Deus (Port of the Name of God) as the instrument, the Salt, perhaps signifying the conversion of that gentile Empire to Catholicism. This is one of the possible interpretations of the symbolism of this illustration. Theodore de Bry was a fifteenth century known editor and a Rosacrucian, for whom the cross- with its higher symbolism of the four arms -and the wheel or rose in the centre, was a pure projection of the previous symbolism of Paradise, the rectangular quadripartite garden with a fountain or tree in its centre. For him, the conquering of the 'small mysteries', or the initial posse of Paradise was already a ante-view of Heaven. LSC

Petits Voyages (Short Travels) which was published by his family after is death in Frankfurt am Main in 1607 (Latin edition). Simplified and relieved of most of its background details, this engraving -possibly a revised production by De Bry - was crowned with the Latin inscription "Non ex quovis ligno fit Mercurius", and at the bottom left, a foreground composition of a tamer forcing a donkey to go through a hoop. In order to hazard a more precise interpretation we would need to know if this engraving was originally accompanied by other plates and/or from which collection or published work, also the order and under which titles, etc. In the meantime, however, we limit ourselves to examining some information from its writings and symbolic compositions. The mentioned Latin quotation, familiar in the enclosed realm of followers of the 'Great Art', or Alchemy, became common idiomatic use with a similar meaning: "It was not from this foul matter that Mercury was extracted". It is known that Mercury, like Sulphur and Salt were the three components of the material prima (primal matter) of the 'Supreme Art', being the basic of Hermetic Philosophy and the affirmation of the unity of matter. These elements did not specifically define the respective chemical substances, but referred to certain qualities of matter. Sulphur defined the active qualities (the forma, the masculine, the active principle) and Mercury the passive properties (the materia, feminine, the passive principle), and Salt, the third element, was their binding force, like the vital spirit that unites body and soul, or the movement thanks to which the active element leaves its mark upon the passive element of all types of forms. With some exceptions, the donkey always arose in all traditions as a symbol of Darkness, the Satanic and Inferior tendencies. Alchemists saw the donkey the three-headed devil (representing Mercury, Sulphur and Salt), or rather the three main substances of Nature, the embodiment of being obstinate. In the allegorical engraving, the tamer of matter, the initiated master (with a staff and the feathers of the illuminato bedecking his forehead), compels the donkey to go through the circular hoop like a circus animal, thus operating the symbolic transformation of matter, thereby beginning the works of the 'Great Task', with vestiges of utopia in the remote view of Macao, the sole Catholic establishment in the vast expanse of China, the Porto do Nome de Deus (Port of the Name of God) as the instrument, the Salt, perhaps signifying the conversion of that gentile Empire to Catholicism. This is one of the possible interpretations of the symbolism of this illustration. Theodore de Bry was a fifteenth century known editor and a Rosacrucian, for whom the cross- with its higher symbolism of the four arms -and the wheel or rose in the centre, was a pure projection of the previous symbolism of Paradise, the rectangular quadripartite garden with a fountain or tree in its centre. For him, the conquering of the 'small mysteries', or the initial posse of Paradise was already a ante-view of Heaven. LSC

In Amor e Dedinhos de Pé (Love and Little Toes), Francisco Frontaria, out of excessive attention to the social codes of the Catholic town's community, was 'condemned' to the most degrading level to the Chinese part of town. The Chinese Market or Bazaar was infernal chaos. In A Trança Feiticeira (The Bewitching Plait), the character Adozindo, also breaking the codes of identity with Catholic society, had to suffer purgatory in exile conditions. Both represent the best of Macao's new generation. However, they had to cross formidable boundaries.

We recently heard of the discreet indignation of the Portuguese community prior to the removal of the statue of the Governor Ferreira do Amaral. It happened almost unnoticed, surreptitiously through the Border Gate, enclosed between the corridors of the new constructions of the consecration of Macao's location. Yet it is like a symbolic devitalisation of the Border Gate which are inscribed with the last epitaph to the sacred aspect of Macao's definite topos. As always, the fall of the symbol was prior to the onset of an adverse reality.

For years this short strip from an isthmus, passageway between a continent and the mainland, was transformed into two bridges serving the main urban sectors, evident in the human army of ants which crossed them all the time.

§ 5. ULYSSES, MACAO'S 'FOUNDER'

Macao is one of those rare cities founded by the Portuguese which was called, "Nome de Deus"("Name of God"). Among the countless names which refer to the place in maps, one should note the special significance of the names "Porta da China"("Gate of China"), and "Porto do Nome de Deus"("Port of the Name of God") (1564). When Dom Duarte de Menezes was Viceroy of Portuguese India, Macao was reconfirmed in 1586 as "Cidade do Nome de Deus na China" ("The City of the Name of God in China"). The confidence shown in the Catholic 'establishment' meant that by 1557 it had been destined to become the centre for religious expansion by the papal Edict Pro Excellenti Proeminentia of Pope Paul IV. Macao was christened as a valuable centre for the missionaries' strategic spreading of Catholicism in the vast Middle Kingdom and Japan. It was the dream of St. Francis Xavier, the visionary, who left Goa for China in 1552 and died in Shangchuan Island. This strategy was already the Jesuit Michele Ruggieri's intention, largely planned by the Visitor Alessandro Valignano and the first protagonist, Matteo Ricci. Macao was not the "City of God" but more the "Name of God", a difference which does not prevent us from attempting to capture the utopian flavour which can be summed up in a comparison within the eschaton of St. Augustine. Although the graces coming down from there to the village were no doubt profoundly felt in the expectations of the Catholic community. The fact was that another confirmation of undetectable origin (as a rule) comes up from the uncertain periods in order to sanctify the place within the most remote heirophantic tradition. This esoteric tradition seeks to bring together some of the 'historical' reinactments to a time and space where the Spirit of the Divine Creator is more alive and present. We are referring to the legend that Macao city was physically founded on seven pillars. Considering that in traditional accounts from the community there is no doubt about the exact number, what interests us (even if it were not so) is to concentrate on the numerical symbolism, the numen locis. In similarity to Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, Luanda and Nagasaki, Macao was chosen as a site of seven hills. The tradition is seen in Lisbon's founding by its eponymous hero Ulysses, also like the mythological founding of Rome. It is interesting to quote Mircea Eliade here again:

Macao is one of those rare cities founded by the Portuguese which was called, "Nome de Deus"("Name of God"). Among the countless names which refer to the place in maps, one should note the special significance of the names "Porta da China"("Gate of China"), and "Porto do Nome de Deus"("Port of the Name of God") (1564). When Dom Duarte de Menezes was Viceroy of Portuguese India, Macao was reconfirmed in 1586 as "Cidade do Nome de Deus na China" ("The City of the Name of God in China"). The confidence shown in the Catholic 'establishment' meant that by 1557 it had been destined to become the centre for religious expansion by the papal Edict Pro Excellenti Proeminentia of Pope Paul IV. Macao was christened as a valuable centre for the missionaries' strategic spreading of Catholicism in the vast Middle Kingdom and Japan. It was the dream of St. Francis Xavier, the visionary, who left Goa for China in 1552 and died in Shangchuan Island. This strategy was already the Jesuit Michele Ruggieri's intention, largely planned by the Visitor Alessandro Valignano and the first protagonist, Matteo Ricci. Macao was not the "City of God" but more the "Name of God", a difference which does not prevent us from attempting to capture the utopian flavour which can be summed up in a comparison within the eschaton of St. Augustine. Although the graces coming down from there to the village were no doubt profoundly felt in the expectations of the Catholic community. The fact was that another confirmation of undetectable origin (as a rule) comes up from the uncertain periods in order to sanctify the place within the most remote heirophantic tradition. This esoteric tradition seeks to bring together some of the 'historical' reinactments to a time and space where the Spirit of the Divine Creator is more alive and present. We are referring to the legend that Macao city was physically founded on seven pillars. Considering that in traditional accounts from the community there is no doubt about the exact number, what interests us (even if it were not so) is to concentrate on the numerical symbolism, the numen locis. In similarity to Lisbon, Rio de Janeiro, Luanda and Nagasaki, Macao was chosen as a site of seven hills. The tradition is seen in Lisbon's founding by its eponymous hero Ulysses, also like the mythological founding of Rome. It is interesting to quote Mircea Eliade here again:  [Commissioner?] regarding payment of ground rent by the Portuguese. </b>Jiaqing 嘉慶 reign, year nineteen[JQ 19=1844]. In: Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo, Lisboa (National Archive of the Torre do Tombo, Lisbon) [ANTT]. </figcaption></figure>

<p>

"[...] Man, in spite of how different determining factors may be in a sacred and profane space, one cannot live except within a sacred space of this kind. He does not expose himself through sacred references but rather builds it using cosmological and geometrical precepts [...]. In fact, a place is never chosen by Man; rather it is simply discovered by him, [...] a sacred area reveals itself to him in another form."

</p>

<p>

At the same time the symbolism of the first sign emerging from chaos, and subterranean currents is a mountainside. It is the prime site for establishing a foundation. A mountainside is the first manifestation of a new cycle, from a ) topos or location, where one takes the new 'egg of fertility of the world' - concentrating on the underlying potentials of the new cycle - symbolised in Noah's ark landing on Mount Ararat after a period of chaos, for example.

topos or location, where one takes the new 'egg of fertility of the world' - concentrating on the underlying potentials of the new cycle - symbolised in Noah's ark landing on Mount Ararat after a period of chaos, for example.

The mountainside determines the principle of emergence which is that of defining and concentrating on an inner sacred aspect that acts as a pivotal point connecting Heaven and Earth. We will not procrastinate on the derivation of mountainside-outside-altarium, and the common root of 'mountain' and 'column' in Portuguese and Latin. What interests us is to say how column concentrates on the same symbol as mountainside, the axis which realigns different levels or worlds, the higher and lower, the human and divine.

Topped by capitals columns are designed like trees, the symbol in some traditions of the Tree of Life.

For the symbolic tradition of seven columns or hills, we have to go look back to the far off mythical period of the Silver Age, prior to the Golden Age, in terms of the Hindu manvantaras and Daniel's dream which he explained to Nebuchadnezzar.

From the time of Atlantis, it spread through several traditions as a nostalgia for "[...] paradise lost [...]", "[...] land of the living [...]", "[...] where God dwells [...]" which is the 'end of the earth' and always in the west. It is like the ancient Tule of Avalon of Saint Brendan's Island.

Quoting Julius Évola:

"It is a place in the west where Enoch himself rules, divine trees guard the Archangel Michael, trees which give life and salvation to the chosen ones but which no mortal can touch until the final judgment." (Book of Enoch, XXIV, 1-6; XXXV, 4-6).

The author also notes:

"As Enoch discovered seven hills in this land, we can see the equivalent in the north-Atlantic Aztlan of the Chicomoztoc, which is to say 'the seven hills'."

Inferred in Avicena is that the Seven Archangels, princes of the Seven Skies, are the Seven Guards of Henoch.

The number seven is one of major symbolic significance, as it is the first perfect number containing both a triad and a tetrad. We know that 'uneven numbers please God' because of the constant presence of seven in Genesis and the Apocalypse, books which begin and end The Bible, thereby indicating the prevalence of the beginning and end of each complete cycle in Christianity.

Symbolising the totality of space and time, seven always seems to indicate a change, in the occurrence or passage of one cycle to another. It is the sign of Rebirth. Therefore the Apocalypse is ordered by the number seven, under the order of the Seven Spirits of God. This highlights the symbolic reasons for the founding of cities 'on seven hills' because, as Eliade said:

"[...] when there is no ancient sacred revelation, a man in need builds them in another way."

It is not by chance that the way Macao's founding, in relation to the legend, can be explained as a basic plan for establishing a city, a legend representing a change and the beginning of a new cycle of mythological representation.

§ 6. NILAU-THE SOURCE OF MEMORY

Both an "Island" and a topos of seven hills symbolically refer to the very same reality: the primordial spiritual centre which appears at the beginning of each cycle of manifestation in pairidacza or paradise. All paradises are described as a circle with a garden at its centre and a tree in the middle, or a mountain, or a spring, which are the same thing in the cosmological sense.

Also "Macao Island", with its seven hills, has a spring at its centre. It is the Fountain of Nilau, a source by which the first oral communication is transmitted to those who reach it before anyone else, according to the myth.

In a notable chapter describing Macao's founding and first settlement (see: The Fountain of Nilau or Grandmother's Well: In Search of the Identity of Macao, in "Review of Culture", Macau, 20 (2)1994, pp.5-11) the historian, Benjamim Videira Pires, gives us the spirit of the urban polarisation around the Fountain of Nilau and Colina da Penha (Penha Hill) transcribed below:

"The Chinese call it the "Spring of the Grandmother's Well or Ancestor's Well [...]. 'Nilau' derives from the Guangdongnese nei-lau (spring from the mountain). The mountain and the spring are associated as representing the two established dimensions of Man and his worldly life: the horizontality or immanence with The matter (the Mater, which always generates even, or especially when, interring); and the verticality, which is enough, in itself, to evoke the transcendence of the spirit. The spring water flows from the heights (clouds and mountains), thus symbolizing the union of Heaven and Earth. Nilau Was the original Chinese name until 1622, of Penha Hill. The Fountain of Nilau was, according to Records dated the 14th of April 1784, "the main fountain of the city" - a pleasant retreat close to the bay, the Temple of Ma-chou (Grandmother-meaning also female ancestor) and the manor house of the Portuguese. With its fengshui (feng = wind + shui = water) or geomancy, its strategic location, and the importance of the vital values in the economy of humankind and other imponderable factors, transformed the Fiountain of Nilau into a kind of myth; a meeting of Luso-Chinese in permanence.

Praya Grande, Macao, 1847.

G. R. West.

Coloured litograph.

Printed by MacLure, MacDonald & MacGregor, London.

"Quem bebe água do Nilau

Não esquece mais Macau;

Ou casa aqui em Macau

ou então volta a Macau."

("Those who drink water from Nilau

Will never forget Macao:

Will either marry in Macao

Or will come back to Macao.").

In paradise, or in some of its representations, the Spring ultimately symbolises the Fountain of Life which feeds paradise as a terra vivens: it is the spirit or the Word of God.

This is the universal parallel of the sacred nature of fountains as the mouth where water springs forth. Within time and space water becomes the manifestation of the arché, materialised symbolically in water. Therefore it is temporal, symbol of maternity and thereby the source of life for all being. Words also come from the mouth (os, oris). For this reason, the spring or fountain also takes on the higher symbolic meaning of Knowledge, the Mother of Knowledge which leads to understanding, a Sophic way which is deeply planted in the Memory, the sacred place of Sophia.

There is no continuity nor perpetuity nor immortality beyond the connecting thread of Memory. Within the classical tradition, the lethal, mortal alternative was to remain in the waters of Lethes: with forgetfulness making Knowledge and Memory of the past life die away.

According to Jung, that symbolism of the archetypal fountain conjures up the image of the very soul. It becomes clear to us that the tradition inherited by us associated to the mythology of the Fountain of Nilau-Spring of the Grandmother's Well or Ancestor's Well―is directly concerned with the various meanings as opposed to the traditional symbolism.

To drink from the fountain is to drink from the origins of life. Those who drink "[...] will come back to Macao,", the inescapable tellurism of returning to one's origins. Or "Will either marry in Macao [...]": religion, reactualized in munus da mater. Or "Will never forget Macao: [...]": an honourable feeling of origins, polarised in the memory which is fundamental to identity and continuity.

As far as our imagination can reconstruct the past, based on various evocations and tales, upon arriving on this land for the first time, they drink from the Nilau. They also made pilgrimages there, those immigrants returning from or visiting, those who live there in the repetition of the hopeful ritual.

All sacred spaces are repeated in primordial hierophania, also all manifestations, 'materialising themselves' and entering into the way of transformations, suffering from factors of corruption and degeneration of substance. Purifying rituals repeat themselves in space like in the symbolic reproduction of the deluge and immediate reconstitution of the pure cosmic act. Regarding water and its sources, the taking of waters and immersions, are all purifying or ritual purifications whose sense in general lies in the restoration of going back to the origins, reenacting the time and place of the archetype of creation, refounding things in their primordial state.

The Nilau's water was the local epiphany of a physical hierophancy for Macao in the past, revealed in the collective subconscious whose pulses were in continuity and eternity in and from the sanctified earth.

§ 7. THE LOCUS AMENUS

In fact we can say the within Macao's mythology we can find the convergence of three elements or waves of hierophanic traditions of the sacred nature of the place; the "Island", the foundation on seven hills, the mythical sources - which reveal a clear intention of the sacred aspect of topos.

More than just a flowing together, the coincidence and juxtaposition of the symbolic substance of the ways integrated with the earth, infer an intention of a sacred concentration which for us is explicable through the basis of a stable Catholic Luso-Asiatic community conscious of its precarious stay there.

Hierophanic evocations (according to Eliade) do not have the sole objective of creating a sacred difference in profane space. In searching for the reconnection between the spiritual principle, they are a ritual or a sacrament which preserves this sacred aspect through time.

"Here in this area the high priest repeats. The place transforms itself in this way from a constant source of energy and purity which allows man, under the condition that he penetrates there, to take part in this force or energy and commune with its sacred nature [...]. The continuity of the high priest, according to the explanation of the eternity of these sacred spaces."

In the memory and expression of generations of citizens living there, Macao has always been described as"[...] the sacred land [...]","consecrated" or "blessed".

Among the factors which identify people from Macao spring to mind the praising of religion and always in the passing of time, the ideal sentiment of edification and preservation of the Greco-Latin topos of the locus amenus.

It is an urban culture living alongside a rural culture, in the transposition of the paradigm of Eden, in harmony with Man and Nature. There is not the time here to introduce the amazingly rich universe of the expanse of earth and water known to Macao (the fengshui = wind + water) as the area of land and water known to Macao as a receptacle of the most beneficial elements and influences. However, it is important to refer to the Western topos of the 'ideal' Garden in Macao and reinforced with a true Chinese life of harmony with Man and Nature and with its worldly divine geography, transmitted also to the universe of the Catholic community. As a result of this there was a close link to the apocalyptic paradigm of Jerusalem, the Garden of the Living where there are walls and vibrant flower beds and diamond shapes. Looking down on the city everything is alive and decorated, urbanisation everywhere, architectural geometry and the crisscross of streets and comers, doors and windows. Everything is alive in a constant flow of influences where everything is reflected in everything else.

Only the light which we mentioned before can be seen to project urban areas of the city outside the visionary designs of Carlos Marreiros, city areas with utopias in their spaces where the forms and trees, the cubist side of nature, refer to an archetypal geometry configured in the mythical topos.

The pure, ingenious lyricism of Adé dos Santos Ferreira, in Macau, Jardim Abençoado (Macao, the Blessed Garden) we quote in patoá (local Dialect):

"Nôsso Macau, nómi sánto; qui ramendá unga jardim; alumiado pa luz divino; Macau quirido, abençoado, Ne-bom, ne-bom disparecê!; cidade di nómi sagrado Vôs nom-pôde disparecê!"

("Our Macao, holy namewhich forms a garden illuminated by divine light, Macao, oh loved, blessed city, It is unfair, so unfair that you disappear!, city with a holy name You must never disappear!").

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce.

See: SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY -- For the following authors and further titles for authors already mentioned in this article.

BACHELARD, Gaston; BERQUE, Augustine; BRAGA, José Maria; BRAZÃO, Eduardo; CAILLOIX, Roger; CALADO, Maria - MENDES, Maria Clara - TOUSSANT, Michel; CENTENO, Yvette - FREITAS, Lima de; CHEVALIER, Jacques - GHEERBRANDT, Alain; CORDIER, Henri; COULANGES, Fustel de; DURAND, Gilbert; ELIADE, Mircea; EVOLA, Julius; FERREIRA, José dos Santos: FREITAS, Jordão de; GRAÇA, Jorge; JESUS, Carlos Augusto Montalto de; LESSA, Almerindo; LJUNGSTEDT, Andrew; MACHADO, Álvaro Manuel; MESQUITELA, Gonçalo; MUMFORD, Lewis; PIRES, Benjamim Videira; SERVIER, Jean; STEWART, Stanley; TEIXEIRA, Manuel; Um olhar sobre Macau.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

•BACHELARD, Gaston, La poétique de l'espace, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1957.

•BERQUE, Augustin, Pensée du lieu et creátion paysagère, at the AICA (ASSOCIATION INTERNATIONALE DE CRITIQUES D'ART), Macau, September 1995 -- [Oral communication].

•BRAGA, José Maria,, The Western Pioneers and their Discovery of Macao, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1949.

•BRAZÃO, Eduardo, Macau Cidade do Nome de Deus na China não há outra mats Leal, Lisboa, Agência Geral do Ultramar, 1957.

•CAILLOIX, Roger, L'homme et le Sacré, Paris.

•CALADO, Maria - MENDES, Maria Clara - TOUSSANT, Michel, Macau: Cidade Memória no Estuário do Rio das Pérolas / Macau: Memorial City on the Estuary of the River of Pearls, Macau, Governo de Macau / Government of Macao, 1985.

•MENDES, Maria Clara - See: CALADO, Maria - MENDES, Maria Clara - TOUSSANT, Michel, Macau: Cidade Memória no Estuário do Rio das Pérolas [...].

•TOUSSANT, Michel -- See: CALADO, Maria - MENDES, Maria Clara - TOUSSANT, Michel, Macau: Cidade Memória no Estuário do Rio das Pérolas [...].

•FREITAS, Lima de -- See: CENTENO, Yvette - FREITAS, Lima de, A Simbólica do Espaço [...].

•CENTENO, Yvette - FREITAS, Lima de, A Simbólica do Espaço: cidades, ilhas, jardins, Lisboa, Estampa, 1991.

•CHEVALIER, Jacques - GHEERBRANDT, Alain, Dictionnaire des symboles, Paris, Robert Laffont - Jupiter, 1982.

•GHEERBRANDT, Alain See:-CHEVALIER, Jacques - GHEERBRANDT, Alain, Dictionnaire des symboles, [...].

•CORDIER, Henri, L'arriveé des Portugais en Chine, in "T'oung Pao", Leiden, (12) 1911.

•COULANGES, Fustel de, A Cidade Antiga, Lisboa, Livraria Clássica Editora, [n. d.].

•DURAND, Gilbert, As Estruturas Antropológicas do Imaginário, Lisboa, Presença, 1989.

•ELIADE, Mircea, Lo Sagrado y lo Profano, Madrid, Guadarrama, 1971.

•ELIADE, Mircea, Imagens e Símbolos, Lisboa, Arcádia, 1979.

•ELIADE, Mircea, Mito y Realidad, Madrid, Guadarrama, 1973.

•ELIADE, Mircea, O Sagrado/Profano, in "Enciclopédia Einaudi", Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional - Casa da Moeda, 1987.

•ELIADE, Mircea, Tratado de História das Religiões, Lisboa, Edições ASA, 1992.

•EVOLA, Julius, Revolta Contra o Mundo Modern, Lisboa, D. Quixote, 1989.

•FERREIRA, José dos Santos, Macau, Jardim Abençoado, Macau Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988.

•FREITAS, Jordão de, Macau - Materiaes para a sua história no século XVI, in "Archivo Historico Portuguez", Lisboa, 3 (5-7) Maio-Julho [May-July] 1910, pp.209-242; 6 (8) 1910. [reprint: Macau 11 (59-61) 1955, pp.149-199; Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988].

•GRAÇA, Jorge, Fortificações de Macau - concepção e história, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1986.

•GRAÇA, Jorge, Fortifications of Macau - Their design and history, in "Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões", Macau, (3)1969. [2nd edition: Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Turismo, 1984].

•JESUS, Carlos Augusto Montalto de, Macau Histórico, Macau, Livros do Oriente, 1990.

•JESUS, Carlos Augusto Montalto de, Historic Macao, Hongkong, Kelly and Welsh, 1902. [reprint: Macau, Salesian Printing Press - Tipografia Mercantil, 1926].

•JESUS, Carlos Augusto Montalto de, Historic Macao: Inter national Traits in China: Old and New, Macau, Salesian Printing Press - Tipografia Mercantile, 1926. [reprint: Hong Kong - New York - Melbourne - Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 1984].

•LESSA, Almerindo, A História e os Homens da Primeira República Democrática do Oriente, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1974.

•LJUNGSTEDT, Andrew, FOLHETIM. Esboço Histórico dos Estabelecimentos Portugueses na China, por Andrew Ljunsgtedt in "Echo Macaense / Semanario Luso-Chinez", Macau, 1 (3), 1 de agosto [August] 1893, p.1; 1 (4) 8 de agosto 1893, p.1; 1 (6) 22 de agosto 1893, p.1; 1 (7) 28 de agosto 1893, p.1; 1 (10) 19 de setembro [September] 1893, p.1; 1 (11) 26 de setembro 1893, p.1; 1(12) 4 de outubro [October] 1983, p.1; 1 (14) 17 de outubro 1893, p.1; 1 (15) 24 de outubro 1893, p.1; 1 (16) 31 de outubro 1893, p.1; 1 (21) 5 de dezembro [December] 1893, p.1; 1 (22) 12 de dezembro 1893, p.1; 1 (24) 27 de dezembro 1893, p.1; 1 (25) 3 de janeiro [January] 1894, p.1; 1 (30) 8 de fevereiro [February] 1894, p.1; 1 (31) 15 de fevereiro 1894, p.1; 1 (34) 7 de março [March] 1894, p.1; "Echo Macaense / Jornal Politico, Litterario e Noticioso", 1 (35) 14 de março 1894, p.1; 1 (36) 21 de março 1894, p.1; 1 (37) 21 de março 1894, p.1; 1 (40) 18 de abril [April] 1894, p.1; 1 (41) 25 de abril 1894, p.1; 1 (42) 2 de maio [May] 1894, p.1; 1 (43) 9 de maio 1894, p.1; 1 (44) 16 de maio 1894, p.1; 1 (45) 23 de maio 1894, p.1; 1 (46) 30 de maio 1894, p.1; 1 (47) 6 de junho [June] 1894, p.1; 1 (48) 13 de junho 1894, p.1; 1 (49) 20 de junho 1894, p.1; 1 (51)4 de julho [July] 1894, p.1; 1 (52) 11 de julho 1894, p.1; 2 (1) 18 de julho 1894, p.1; 2 (2) 25 de julho 1894, p.1; 2(5) 15 de agosto 1894, p.1; 2 (7) 29 de agosto 1894, p.1; 2 (9) 12 de setembro 1894, p.1; 2 (11) 27 de setembro 1894, p.1; 2 (12) 8 de outubro 1894, p.1; 2 (14) 17 de outubro 1894, p.1; 2 (16) 31 de outubro 1894, p.1; "Echo Macaense / Jornal Politico, Noticioso e Litterario", 2 (21) 5 de dezembro 1894, p.1; 2 (22) 12 de dezembro 1894, p.1; 2 (24) 26 de dezembro 1894, p.1; 2 (28) 28 janeiro 1895, p.1; 2 (30) 6 de fevereiro 1895, p.1; 2 (39) 10 de abril 1895, p.1; 2 (41) 24 de abril 1895, p.1; 2 (45) 22 março 1985, p.1; 2 (50) 26 junho 1895, p.1; 2 (51) 3 de julho 1895, p.1; 2 (52) 10 de julho 1895, p.1; 3(1) 17 de julho 1895, p.1; 3 (6) 21 de agosto 1895, p.1; 3 (17) 6 de novembro [November] 1895, p.1; 3 (19) 9 de fevereiro 1896, p.1; 3 (20) 16 de fevereiro 1896, p.1; 3 (21) 23 de fevereiro 1896, p.1; 3 (24) 15 de março 1896, p.1; 3 (25)22 de março 1896, p.1; 3 (30) 24 de abril 1896, p.1; 3 (32) 10 de maio 1896, p.1; 3 (33) 17 de maio 1896, p.1; 3 (39) 28 de junho 1896, p.1; 4 (1) 19 de julho 1896, p.1; 4 (6) 28 de agosto 1896, p.1; 4 (7) 30 de agosto 1896, p.1; 4 (12) 4 de outubro 1896, p.1; 4(14) 18 de outubro 1896, p.1; 4 (15) 25 de outubro 1896, p.1; 4 (17) 8 de novembro 1896, p.1; 4 (19) 22 de novembro 1896, p.1; 4 (20) 29 de novembro 1896, p.1; 4 (21) 6 de dezembro 1896, p.1; 4 (22) 13 de dezembro 1896, p.1.

•MACHADO, Álvaro Manuel, O mito do Oriente na Literatura Portuguesa, Lisboa, ICLP, 1983.

•MESQUITELA, Gonçalo, História de Macau, 2 vols., Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1996.

•MUMFORD, Lewis, A Cidade na História, Brasília, Universidade de Brasília, [n. d.].

•PIRES, Benjamim Videira, Os Extremos Conciliam-se: transculturação em Macau, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988.

•SERVIER, Jean, Histoire de L'Utopie, Paris, Gallimard, 1967.

•STEWART, Stanley, The Enclosed Garden, Madison, Wisconsin University Press, 1966.

•TEIXEIRA, Manuel, Macau através dos séculos, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1977.

•TEIXEIRA, Manuel, Macau no século XVI, Macau, Direcção dos Serviços de Educação e Cultura, 1981.

• Um olhar sobre Macau, Lisboa, Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical - Fundação Oriente, 1991.

start p. 5

end p.