INTRODUCTION

The over three hundred works of art by the English painter George Chinnery on display at the Tourism Activities Centre [Centro de Actividades Turistícas] have as their main theme the city of Macao. After more than four hundred years as a Portuguese settlement, Macao is soon to be returned to China. This is, therefore, a very timely exhibition, put together thanks to the initiative of the Orient Foundation [Fudação Oriente] and now of The Macao Territorial Commission for the Commemoration of Portuguese Discoveries [Comissção Territorial de Macau para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses].

For the most part the pictures on display follow the catalogue and classification I made for the 1995 Lisbon exhibition. However, there have been important new additions with eleven drawings from The British Museum I believe have not been seen in an exhibition before. There is also a return showing of thirty works from the Oriental Library [Toyo Bunko] of Tokyo's collection, as well as several from that of the Urban Council [Leal Senado] of Macao. They take the place of other Chinnery pictures which could not be shown this time, including his portraits, and this has meant a reclassification of subject matter.

The exhibition brings to life a Macao of a century-and-a-half ago, a very different place from the Macao that is to be handed back. At that time its unique Sino-Portuguese character was still largely intact, when Chinnery's industrious pencil and brush first recorded it for posterity.

As has previously been remarked by a number of scholars, Chinnery's art reached maturity during the years of his abode in Macao, a period running from 1825 to 1852. After a highly successful practice as portrait painter in British settlements in India, Chinnery opted for the self-imposed life of an exile in the Portuguese colony in China. The founding of Hong Kong in 1842 seems to have made very little difference to him. Apart from one trip to the burgeoning British colony, Chinnery chose to remain in Macao for the remainder of his life.

Luckily for students of his art and of nineteenth century Macao, the artist was captivated from the first by the city's old colonial buildings, squares and streets, as well as by its lively Chinese population and its culture. The city was by then already divided into the so-called Christian City, or the intramural Portuguese quarters, and a Chinese City, partly outside those walls. Equally important, residents of the Catholic City included a small but powerful British and American merchant community, providing the painter with a group of potential patrons.

CATALOGUING OF WORKS

The visitor will see a selection of works depicting sights, scenes and persons from both quarters. The selection is intended to be representative rather than exhaustive. These works are of medium and small size, although most of the techniques used by Chinnery as a draughtsman are represented. These include watercolours on paper and a variety of drawing techniques, of which pencil on paper, often later outlined with pen and sometimes with sepia ink or wash, was the most commonly used by the artist. To have a complete understanding of Chinnery's creative powers it is necessary to study his large portraits. But many of these fall outside the main aims and possibilities of this exhibition and were, therefore, excluded.

Macao and its inhabitants are shown to the public in the galleries chiefly filtered through a variety of drawings. These drawings served different purposes and the cataloguing of works should make the latter evident.

The totality of works have been catalogued chronologically and by subject matter. As display and catalogue are trilingual, an alphabetical order was avoided.

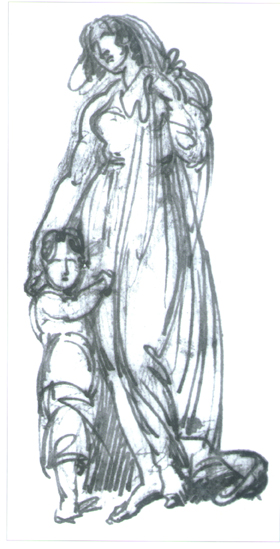

Illustration 1

Mother and Child

[n. d.]. Ink on paper. [dimmensions not supplied].

The British Museum collection, London. [GC: INCM: Foreword/Introduction, p.20, ill.1]

Illustration 1

Mother and Child

[n. d.]. Ink on paper. [dimmensions not supplied].

The British Museum collection, London. [GC: INCM: Foreword/Introduction, p.20, ill.1]

Presentations of Chinnery's works according to a strict chronology are rare. Even this exhibition does not make unrealistic claims regarding the exact chronology of the works. Chinnery seldom signed or dated his oil paintings and watercolours. What often stands for a signature, the Gurney shorthand notes and dates that accompany some of his drawings and sketches, can only be deciphered today by experts.

A few of Chinnery's contemporaries in England also used shorthand notes. Our artist first began using them to any significant extent in his Bengal drawings in India, and later in Macao. Drawings with shorthand notes and dates are, therefore, one of the ways in which it becomes possible to begin to establish something like an order, amongst the numerous drawings belonging to this phase.

STYLISTIC DEVELOPMENT

After attempting to establish a chronological sequence for the works in the exhibition, the juxtaposing of drawings and paintings disclosed interesting facts regarding Chinnery's style in Macao. Before his arrival in the territory, the artist's pen and pencil were vibrant but somewhat rigid. His figure sketches in India still enclosed the figure in that thick outline and hard hatching and crosshatching that he had learnt as a youth at the Royal Academy Schools. During the 1830's in Macao, however, his outline becomes thinner, his touch more expressive and his lines wavy and broken. A good contrast is provided by the figure of the mother and children in the exhibition (Exhibit 231), 1 and a youthful academic study of a mother and child in a more sculptural, Neoclassical manner illustrated here (Illustration 1). Similar comparisons could be made between his watercolour landscapes in India and Macao.

However, at least some of Chinnery's portraits and other painted works seem to have gained in dramatic depth during the Forties. His famous selfportrait, a work exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1846, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, London, shows a different grave mood. It must be remembered that to his contemporaries, Chinnery was recalled as being a jocund Dickensian man.

Probably the most difficult works to insert within the stylistic development evident in earlier works are a group that have been given the date1850-1852. These are drawings that were found amongst those of more certain authorship in the Geography Society of Lisbon [Sociedade de Geografia] de Lisboa collection.

Based on two dated sheets of sketches (Exhibits 247, 2324), 3 this puzzling group of drawings were all dated to the last few years of Chinnery's life. Could they be proved conclusively to be by his hand, they would certainly rated amongst the most valuable of his works for students of his art.

However, the lines of several of the drawings appear weak and amateurish. At least one of the works included in the exhibition can be shown to be a less polished pencil replica of an ink and watercolour painting by Dr. T. B. Watson, one of Chinnery's pupils (Exhibit 320). 4Also the sheet with the head of an Indian is virtually a copy of the pencil portrait of a turbaned Moslem, one of Chinnery's most accomplished portrait drawings (Exhibit 325). 5

These drawings could be explained as being either creations by an aged weak-sighted and already feeble-minded Chinnery, or works by pupils submitted to the master for correction., For this reason, they have been catalogued as works attributed to Chinnery. On stylistic grounds, a few other works from other collections have also been placed in this group.

SUBJECT MATTER

Already during his years of practice as fashionable portrait painter in India, Chinnery had found it difficult to finish his portraits. As we may verify today, and as several contemporary sources report, the artist much preferred landscape painting, or going out early in the morning sketching. One of the reasons that Macao became so attractive to him, is that it allowed him to indulge himself in his favourite types of art. The works seen in this display are exceptional examples of Chinnery's favourite themes, executed in media in which he enjoyed working. His delight in them gradually communicate itself to the visitors.

Themes include not only landscapes proper, but paintings and drawings of city views and street scenes.

The exhibition is fortunate to count amongst its exhibits of city scenes and landscapes an impressive set of drawings and paintings from the lending institutions. These consist mainly of scenes from various spots along Praya Grande [Praia Grande], a few from the Inner Harbour [Porto Interior], and more numerous, intimate views of Macao's colourful colonial and Chinese architecture. It is necessary to point out that two of the mentioned genres, mainly landscape and city views, had come into their own in England through the influence of the Italian painter Antonio Canal, or Canaletto. During the second half of the eighteenth century, it was largely through his works that the concepts, first of naturalistic landscape, then of vedute, and capricci for city views, had evolved in England. It was left to painters of Chinnery's generation to invent English Romantic landscape. The separation of the two genres was, therefore, a comparatively recent development and Chinnery should be considered as one of the earlier and, as regards subject-matter, most original interpreters of these kinds of pictures.

In Chinnery's works the veduta or city view is capable of further classification. The kind of painting or drawing represented by his sweeping views of the Praya Grande could be classed on their own (Exhibit 42). 6 They are a development of the pictures of townscapes which first became popular in Europe at the end of the sixteenth century through prints appearing in books of towns. They imply that their patrons would experience an enjoyment similar to that provided by the more popular panorama.

Exhibit 325

Head of Indian and sketch of gamblers

ca 1850. Pencil on paper. 318x215 mm.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon) collection, Lisbon. [GC: INCM: Attributed Drawings, p.167, i11.325]

Exhibit 325

Head of Indian and sketch of gamblers

ca 1850. Pencil on paper. 318x215 mm.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon) collection, Lisbon. [GC: INCM: Attributed Drawings, p.167, i11.325]

The many views of Macao's main 'beauty spots' are closer to the idea of veduta. The pictures of St. Lawrence's [São Lourenço] Church, those of the Misericordy's [Santa Casa da Misericórdia] Church or of St. Dominic's [São Domingos] Church and square should be viewed in this light. The latter also applies to the entrancing views of the Ma Kwok [A-Ma or Ama] Temple or the various folly-forts in Canton [Guangdong].

Apart from these two, there is a third grouping of works more directly involved with the inhabitants of the town. This third type of work, whose theme is found in oil paintings, watercolours, drawings and prints, is that of the street scene or street life of the local Chinese.

The latter became for Chinnery almost exclusively village people or fishermen and their families. Except in large commissioned portraits, the artist never shows wealthier Chinese of the mandarin class, of which many were to be seen in the area at the time, or Chinese of high rank. The same applies to Europeans of whatsoever station in life, although the occasional silhouette of monks, priests or soldiers, presumably Portuguese, may be seen in sketches of vedute pictures. In the latter, a quite popular figure with Chinnery is that of the Macanese lady going or coming from church, dressed in the traditional, but today obsolete, costume known as the 'do'.

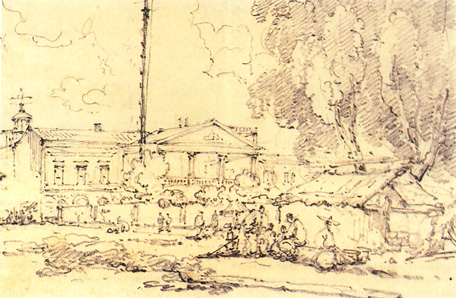

Exhibit 96

English East India Factory from Hog Lane

1832. Pencil on paper. 125 x 175 mm.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon) collection, Lisbon.

[GC: INCM: Views of Canton, p.98, i11.96]

Due to the nature of the exhibition, most of the above genres are represented without the benefit of colour. Even then, Chinnery's pencil and pen magically convey the many sounds, smells and colours of his scenes. Moreover, works on loan from the collections of the Toyo Bunko and from the Hong Kong Museum of Art are watercolours, thus allowing us to enjoy the colour harmonies peculiar to Chinnery's palette. This is particular true of his vermilions, blacks and luminous whites and blues.

One of the more satisfactory results of studying the works selected for exhibition is that several of the locations seen in the drawings are now correctly identified. A good example is the view of the English East India Factory from Hog Lane, in Canton [Guangzhou] (Exhibit 96). This was originally thought to be the same building, but seen from the Praya Grande, in Macao. The same applies to the drawing of a church portal which was thought to have been that of St. Dominic's Church (Exhibit 56). 7 A similar sketch in the collection of Prints and Drawings of The British Museum with a view of the Misericordy Square underneath, shows it to belong to the portal of the Misericordy Church.

Many of the sites, buildings and street characters inhabiting Chinnery's more finished drawings, watercolours and oil paintings had been assiduously thought out and rehearsed in a variety of drawings.

These drawings, included in the exhibition under the headings of preliminary figure sketches and drawings, rough sketches and studies, were, in fact, preliminary steps in the creative process. Included in this type of work are the two small albums on display. The sheets of drawings as well as the albums give an indication of the kinds of formats, techniques and papers used by the artist.

As regards the actual themes represented in the drawings, it could vary according to the nature of the work. It could be a mere sketch of an idea, which may or may not evolve into a more evolved drawing or painting. It could be a study of an architectural feature, as above. In the case of figures, the themes could range from a sketch of a European or groups of members of the British community, possibly to serve for a later portrait, to sketches of street gamblers or boat girls and fisher youths.

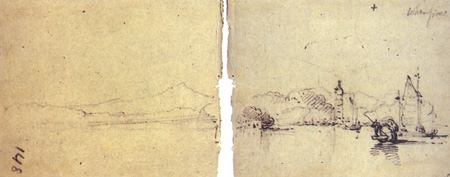

Exhibit 296

Whampoa landscape

ca1830-1832. Pencil on paper. 62 x 75 mm.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon) Collection, Lisbon.

[GC: INCM: Preliminary Figure Sketches, p.158, i11.296]

The way that these figures or other sketches were put down on paper is also worth studying. Extremely quick sketches, as in some of those seen in the second album on display, appear as almost abstract shapes. Mainly due to the miniature landscapes of Whampoa which form part of the album (Exhibits 296, 299), these sketches have been dated to 1832 in this catalogue. Chinnery stayed most of that year in Canton [Guangzhou].

Here, the bare outlines of one of his favourite subjects, the Chinese barber could be thought of as his equivalent of the modern snapshot. It is interesting to note that Chinnery's quick eye and hand, well practiced in the rapid writing skills of shorthand, arrived at forms that would have appealed to a Cubist or other modern painter.

These first impressions were normally considered by Chinnery — and by his peers in Europe — to be little more than initial thoughts, later to be reworked and perhaps incorporated into a more formal composition for a painting. But his very preoccupation with first impressions, be it of figures or of nature, executed on the spot, makes us realize just how innovative he could be.

A small sketch of a tanka boat girl in the upper, left-hand corner of a sheet on loan from The British Museum gives us a glimpse into the evolution of an idea and a first impression (Exhibit 203). It bears the date "September, 1840" and the girl in question is evidently Assor, Chinnery's favourite female model. In this small sketch she holds a hand to her kerchief and glances flirtatiously at us, or rather, at the artist. This small sketch could well be the germ of an idea of several paintings of her in similar pose that Chinnery did of her, as could another sketch dated 1851 on the verso of a sheet of figure sketches from the Geography Society of Lisbon (verso of 247, not illustrated). This kind of sketch let us witness in a very special way the very first moments of inspiration. For this reason, they maintain a freshness of observation not seen in more finished works.

Exhibit 299

Whampoa landscape

ca 1830-1832. Pencil on paper. 62 x 75 mm.

Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa (Geography Society of Lisbon) collection, Lisbon. [GC: INCM: Preliminary Figure Sketches, p. 159, i11.299]

Harriet Low, the young lady from Philadelphia who was one of Chinnery's pupils, writes in her dairy that the artist's profession had brought him into contact "[...] with people of high and low degrees." As a result, Chinnery had become "[...] a great observer of human nature." When it came to human types Chinnery's interest in people of "[...] low degree [...]," as the exhibits shown indicate, was evidently stronger than other interests. In this respect he was something of an ethnologist and something of a novelist. In this latter pursuit Chinnery must have been greatly encouraged by the French painter Auguste Borget. Borget befriended Chinnery during his short stay in Macao at the end of 1838. Their unique drawings of boat dwellings and boat dwellers is proof enough. Borget's friendship with the novelist Honoré de Balzac throws further light on the nature of their relationship.

Chinnery's interest in realism, dormant since his student days, reemerged more fully in Macao. However, his love of street scenes is still a far cry from the kind of 'social realism' that would develop in France later in the century. Chinnery's pictures, including his figure sketches of village people and fisher folk, were created with the paintings intended for the drawing rooms of people of 'high degree' in mind. His peasants and boat people, therefore, often recall the idealized rural folk of pastoral landscapes.

The artist's love for life in general speaks to us through his works. It included all human types, regardless of social standing, race, sex, age or occupation. It extended to the enchanting countryside surrounding the old city. It embrace Macao's quaint streets and squares, elegant mansions and picturesque churches. Hopefully this exhibition will make possible a deeper appreciation of Chinnery's art and of the Macao his brush and pencil now brings to life. ***

Exhibit203

Boatgirl and other figures

1840. Sepia ink on paper. 107 x 296 mm.

The British Museum collection, London. [GC: [NCM: Preliminary Figure Sketches, p. 142, i11.203]

NOTES

1 See: CHINNERY, George, Album, in "Review of Culture", Macao, 2 (33) October/December 1997, p.191, i11.70.

2 See: Ibidem., p. 168, ill.42.

3 See: Ibidem., p.189, i11.58.

4 [GREGORY, Martyn], Catalogue 40, London, Martyn Gregory Gallery, 1985, p.32, i11.19.

5 CONNER, Patrick, George Chinnery, 1774-1852. Artist of India and the China Coast, Woobridge, 1993, p.95, plate 53.

6 See: CHINNERY, George, op. cit., p.172, i11.4.

7 See: Ibidem., p.174, ill.8.

Exhibit 203

Boatgirl and other figures

***In: George Chinnery: Imagens de Macau Oitocentista/ George Chinnery: Images of Nineteenth-Century Macao, [Trilingual Exhibition Catalogue: 11 Out./Oct. - 18 Nov., 1997 —Centro de Actividades Turísticas: Fórum de Macau / Tourist Activities Centre: Macao Forum], Macau, Comissão Territorial de Macau para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses / The Macao Territorial Commission for the Commemoration of Portuguese Discoveries, 1997, pp.35-41.

* Historian of Western art, writer and researcher on colonial Portuguese and Spanish art. He has an M. Phil. from University College London, University of London (1997), an M. A. from Pennsylvania University, as well as a B. A. from the Courtauld Institute of Art (1973), London.

Professionally he is mainly a curator of art exhibitions and writer on colonial and modern art, but he has also been a lecturer in the History of Western Art in local universities. More recently he is a Guest Curator of the Government of Macao. In the past he has curated exhibitions for the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation), at the Centro Cultural de Belém (Belém Cultural Centre), Lisbon, as well as for the Serviços Recreativos e Culturais (Cultural and Recreational Services) of the Leal Senado (Urban Council) of Macao and the Hong Kong Museum of Art. These have included both China Trade artists and contemporary artists. Guest curator of the 'George Chinnery' exhibition.

start p. 155

end p.