[...]

Now I will speak of the manner the which the Chins do observe in doing justice, that it may be known how far these Gentiles do herein exceed Christians, that be more bounden than they do deal justly and in truth. 1 Because the king of China maketh his abode continually in the city of Pachim, · his kingdom so great, the shires so many, as tofore it hath been said: in it therefore the governors and rulers, much like unto our sheriffs, be so appointed suddenly and speedily discharged again, that they have no time to hatch ill. Furthermore to keep the state in more security, the Louteas·2 that govern one shire, are chosen out of some other shire distant far off, where they must leave their wives, children and goods, carrying nothing with them but themselves. {1} True it is, that at their coming thither they do find in a readiness all things necessary, their house, furniture, servants, and all other things in such perfection and plenty, that they want nothing. Thus the king is well served without fear of reason.

In the principal cities of the shires be four chief Louteas, before whom are bought all matters of the inferior towns, throughout the whole shire. Divers other Louteas have the managing of justice, and receiving of rents, bound to yield an accompt thereof unto the greater officers. Others do see that there be no evil rule kept in the city; each one as it behoveth him. Generally all these do imprison malefactors, cause them to whipped and racked, a thing very usual there, and accompted no shame. 3 These Louteas do use great diligence in the apprehending of thieves, so that it is a wonder4 to see a thief escape away in any town, city or village. Upon the sea near unto the shore many are taken, and look even as they are taken, so be they first whipped, and afterward laid in prison, where shortly after they all die for hunger and cold. At that time when we were in prison, there died of them above threescore. 5 If haply any one, having the means to get food, do escape, he is set with the condemned persons, and provided for as they be by the king, in such wise as hereafter it shall be said.

Their whips be bamboos, cleft in the middle, in such sort that they seem rather plain than sharp. He that is to be whipped lieth groveling on the ground. Upon his thighs the hangman layeth on blows mightily with these bamboos, that the standers-by tremble at their cruelty. Ten stripes draw a great deal of blood, twenty or thirty spoil the flesh altogether, fifty or threescore will require a long time to be healed, and if they come to the number of one hundred, then they are incurable -- and they are given to whatsoever hath nothing wherewith to bribe these executioners who administer them. {2}

The Louteas observe moreover this: when any man is brought before them to be examined, they ask him openly in the hearing of as many as be present, be the offence never so great. Thus did they also behave with us. For this cause amongst them can there be no false witness, as daily, amongst us it falleth out, whence it often happens that men's goods, lives and honours are imperilled by being placed in the hand of a dishonest notary. 6{3} This good cometh thereof, that many being always about the judge to hear the evidence, and bear witness, the process cannot be falsified, as it happeneth sometimes with us. The Moors, Gentiles, and Jews, have all their sundry oaths; the Moors do swear by their moçafa, 7{4} the Brahmans by their sacred thread, 8{5} the Jews by their Torah, 9{6} the rest10 likewise by the things they do worship. The Chins though they be wont to swear by heaven, by the moon, by the sun, and by their idols, in judgement nevertheless they swear not at all. If for some offence an oath be used of anyone, by and by with the least evidence he is tormented; so be the witnesses he bringeth, if they tell not the truth, or do in any point disagree, 11 except they be men of worship and credit, {7} who are believed without any further matter; the rest are made to confess the truth by force of torments and whips.

And as for questioning the witnesses in public, besides not confiding the life and honour of one man to the bare oath of another, this is productive of another good, which is that as these audience chambers are always full of people who can hear what the witnesses are saying, only the truth can be written down. In this way the judicial processes cannot be falsified, as sometimes happens with us, where what the witnesses say is known only to the examiner and notary, so great is the power of money, etc. But in this country, besides this order observed of them in examinations, they do fear so much their king, and he where he maketh his abode keepeth them so low, that they dare not once stir; in sort that these men are unique in the doing of their justice, more than were the Romans or any other kind of people.

Again, these Louteas as great as they be, notwithstanding the multitude of notaries they have, not trusting any others, do write all great processes and matters of importance themselves. Moreover one virtue they have worthy of great praise, and that is, being men so well regarded and accompted of as though they were princes, they be patient12 above measure in giving audience. We poor strangers brought before them might say what we would, as all to be lies and falacies that they did write, neither did we stand before them with the usual ceremonies of that country, yet did they bear with us so patiently, that they caused us to wonder, knowing specially how little any advocate or judge is wont in our country to bear with us. And if the wand of office were taken from any one of our judges they could very well serve any one of these Chins, -- disregarding the fact that these are heathen; 13 and as for their being heathen, I do not know a better proof of praising their justice than the fact that they respected ours, we being prisioners and foreigners. 14 For wheresoever in any town of Christendom should be accused unknown mean as we were, I know not what end the very Inncocents' cause would have; but we in a heathen country, having for our great ennemies two of the chiefest men in a whole town, 15 wanting an interpreter, ignorant of that country language, 16 did in the end see our great adversaries cast into prison for our sake, and deprived of their offices and honour for not doing justice, yea not to escape death, for as the rumour goeth, they shall be beheaded -- now see if they do justice or no? 17{8}

Somewhat is now to be said of the laws that I have been able to know in this country, and first, no theft or murder, is at any time pardoned: adulteres are put in prison, and the fact once proved, condemned to die; the woman's husband must accuse them. This order is kept with men and women found in that fault, but thieves and murderers are imprisoned as I have said, 18 where they shortly die for hunger and cold. If any one haply escape by bribing the gaoler to give him meat, his process goeth further, and cometh to the Court where he is condemned to die. Sentence being given, the prisoner is brought in public with a terrible band of men that lay him in irons hand and foot, with a board at his neck one handful thick, in length reaching down to his knees, cleft in two parts, and with a hole one handful downward in the table fir for his neck, the which they enclose up therein, nailing the board fast together; one handful of the board standeth up behind the neck. 19 The sentence and cause whereof the fellon was condemned to die, is written in that part of the table that standeth before. {9}

This ceremony ended, he is laid in a great prison in the company of some other condemned persons, the which are found by the king as long as they live. The board aforesaid so made, tormenteth the prisioners very much, keeping them both from rest, and eke letting them to eat commodiously, their hands being manacled in irons under that board, so that in fine there is no remedy but death. 20

In the chief cities of every shire, as we have erst said, there be four principal houses, in each of them a prison: but in one of them where the Taissu•21 maketh his abode, there is a greater and a more principal prison than in any of the rest; and although in every city there be many, nevertheless in three of them remain only such as condemned to die. Their death is much prolonged, for that ordinarily there is no execution done but once a year, though many die for hunger and cold, as we have see in this prison. {10} Execution is done in this manner. The Chaem, •22 to wit the High Commissioner or Lord Chief of Justice, as the year's end goeth to the head city, where he heareth again the causes of such as be condemned. Many times he delivereth some of them, declaring that board to have been wrongfully put about their necks. The visitation ended, he chooseth out seven or eight, not many more or less, according to his good or ill disposition, of the greatest malefactors, the which to terrify and keep in awe the people, are brought into a great field, where all the great Louteas meet together, and after many ceremonies and supertitions, as the use of the country is, are beheaded. This is done once a year: who so escapeth that day, may be sure that he shall not be put to death all that year following, and so remaineth at the king's charges in the great prison. In that prison where we lay were always one hundred and more of these condemned persons, besides them that lay in other prisons. {11}

These prisons wherein the condemned catiffs do remain are so strong, that it hath not been heard that any prisoner in all China hath escaped out of prison, for indeed it is a thing impossible. The prisons are thus builded. First, all the place is mightily walled about, with its watch-tower above, the walls be very strong and high, the gate of no less force. Within it three other gates, before you come where the prisoners do lie; there many great lodgings are to be seen of the Louteas, Notaries, Parthions, ·23{12} that is, such as do these keep watch and ward day and night; the court large and paved, on the one side whereof standeth a prison, with two mighty gates, wherein are kept such prisoners as have committed cruel crimes. This prison is so great, that in it are streets and market places wherein all things necessary are sold. Yea some prisoners live by that kind of trade, buying and selling, and letting out beds to hire. Some are daily sent to prison, some daily delivered, wherefore this place is never void of seven or hundred men that go at liberty. 24

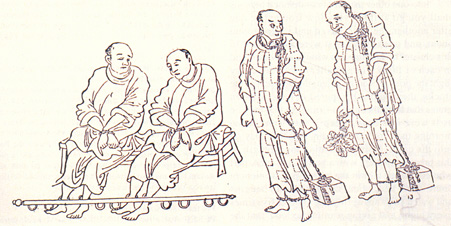

Chinese prisoners.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, HINO, Hiroshi, trans. [into Japanese], Tratado das Cousas da China [...] (Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]), Tokyo, 1989, p.308.

Chinese prisoners.

In: CRUZ, Gaspar da, HINO, Hiroshi, trans. [into Japanese], Tratado das Cousas da China [...] (Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]), Tokyo, 1989, p.308.

Into one other prison of condemned persons shall you go at three very low iron gates, one after another, the court paved and vauted round about, and open above as it were a cloister. 25 In this cloister be eight rooms with iron doors, 26 and in each of them a large gallery, wherein every night the prisoners do lie at length, their feet in the stocks, their bodies hampered in huge wooden grates that keep them from sitting, so that they lie as it were in a cage, sleep if they can; in the morning they are loosed again, that they may go into the court. Notwithstanding the strength of this prison, it is kept with a garrison of men, part whereof watch within the house, part of them in court, some keep about the prison with lanterns and watch-bells answering one another five times every night, and giving warning so loud, that the Loutea resting in a chamber not near thereunto, may hear them. In these prisons of condemned persons remain some fifteen, others twenty years imprisoned, not executed, for the love of their honourable friends that seek to prolong their lives. 27 Many of these prisoners be shoemakers, and have from the king a certain allowance of rice. Some of them work for the keeper, who suffereth them to go at liberty without fetters and boards, the better to work. Howbeit when the Loutea calleth his checkroll, and with the keeper vieweth them, they all wear their liveries, that is, boards at their necks, ironed hand and foot.

When any of these prisoners dieth, he is to be seen by the Loutea and Notaries, brought out at a gate so narrow, that there can but one be drawn out there at once. The prisoner being brought forth, an iron-tippe stave; that done, he is delivered unto his friends if he have any, otherwise the king hireth men to carry him to his burial in the fields.

For the original source of the English translation see:

[PEREIRA, Galiote], Certain Reports of China, learned through the Portugals there imprisoned, and chiefly by the relation of Galeote Pereira, a gentleman of good credit, that lay prisoner in that country many years. [...]., in BOXER, Charles Ralph, ed., [Camões Professor of Portuguese, University of London, King's College], in "South China in / the Sixteenth Century/[Being the narratives of/ Galeote Pereira / Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O. P. / Fr. Martín de Rada, O. E. S. A./(1550-1575)]", London, Hakluyt Society, 1921 [second series, No. CVI] (issued for 1953), pp.17-24.

Ibidem, p. vii -- "The translation of the narrative of Galeote Pereira is based on Richard Willis' translation in the History of Trauayle in the West and East Indias and other countries lying either way towards fruitfull and ryche Moluccas (London, 1577), leaves 237-251 [misprinted 253], which, in its turn, was taken from the Italian version printed in the Nuovi Avisi delle Indie di Portogallo... Quarta Parte (Venice, 1565), pp.63-87. I have carefully compared Willis' version with the Portuguese manuscript copies of Pereira's original report which are preserved in the Archives at Lisbon and Rome, and made additions and alterations to Willis' text as proved to be necessary."

For the Portuguese text, see:

PEREIRA, Galiote, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Agumas Coisas Sabidas da China, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.53-56 -- For the Portuguese modernised version by the author of the original text, with words or expressions in square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese text, see: PEREIRA, Galiote, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, ed., Algumas cosas sabidas da China, Lisboa, Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses- Ministério da Educação, 1992, pp.29-36 -- Partial transcription.

NOTES

The numeration of these notes specifically refer to the section of Galiote Pereira's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, p.65.

The prevailing numeration of these notes is indicated between curly brackets《{ }》and is cross-referenced to Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation [CRB] of Galiote Pereira's original text, indicated immediately after, in between flat brackets《[ ]》.

The contents of these notes have been transferred in their entirety exactly as they appear in Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation [CRB] of Galiote Pereira's text, and do not follow the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture". Whenever followed by a superciliary asterix《*》, these notes' bibliographic references are alphabetically repertoried according to their author's name in this issue's SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY following the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

{1} [CRB, p.18, n.1] João de Barros, Decada III, Livro 2, cap. vii (Lisbon, 1563), compares this system to 'a maneira que neste Reyno de Portugal se vsam os juizes que chamam de fóra', which was instituted in Portugal with the same object of preventing magistrates being influenced by ties of local kinship or friendship. Other Portuguese contemporaries were more critical of this practise. Cf. introduction, pp. xxx-xxxi.

{2} [CRB, p.19, n.1] Descriptions of beating with the bamboo, and of the various types of bamboo used, will be found in The Punishments of China* (London, 1804), PI. IV; G. Staunton, Ta Tsing Leu Le... The penal codes of China* (London, 1810), p. lxxiv; and in the Ta Ming Hui-tien, • chüan 178. The Ming· practice was not radically different from that obtaining under the Manchus.

{3} [CRB, p.19, n.2] This unfavourable comparison of European with Chinese justice was drastically abridged by the Italian censor, and so appears in a very truncated form in the previously printed versions. The practise of trial in open court lapsed under the Manchu dynasty. Cf. Gray, China,* I, 32-33.

{4} [CRB, p.19, n.3] Mushaf, a volume or book; hence the Koran. Cf. Dalgado, Glossário Luso-Asiático, *II,58.

{5} [CRB, p.19, n.4] The sacred thread of Janeu, which is, however, not the monopoly of the brahmans but is shared by the first three castes. Cf. Dalgado, Glossário Luso-Asiático, I, 527-529; S. Sen, Indian Travels of Thevenot and Careri* (New Delhi, 1949), p.385n(15).

{6} [CRB, p.19, n.5] The Torah or Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament regarded as a connected group, and whose authorship was often ascribed to Moses.

{7} [CRB, pp.19-20, n.6] The Shên-shih, ·or 'girdled scholars', otherwise known as the 'scholar-gentry'. Defined by Morse as 'unemployed officials, men of family, of means and of education, living generally on inherited estates, controlling the thoughts and feelings of their poorer neighbours and able to influence the action of the officials'. Couling,* Encyclopedia Sinica, p.511. The exemption from torture probably referred more specifically to the 'eight priviliged classes'. Cf. clauses 404 of the Ch'ing· penal code in Staunton's Penal Code of China, 1810 and Mayers, Chinese Reader's Manual*(ed. 1910), p.353.

{8} [CRB, p.21, n. 1 ] This long eulogy of Chinese justice was drastically abridged by the Italian censor, and hence in the English version of 1577. Cf. p. 19 note (2) above, and p. xxix of the introduction.

{9} [CRB, p.21, n.2] The portable pillory or cangue (chia· in Chinese), illustrations of which will be found in the accompanying woodcuts from a Ming book. The efforts of English lexicographers to derive the word 'cangue' from the Portuguese canga (ox-yoke), receive no support from Dalgado who points out that none of the old Portuguese writers on China use such a word before c.1640. He suggests that it was probably derived from the Annamite gang. Dalgado, Glossário Luso-Asiático, I, 203-204.

{10} [CRB, p.22, n.1] 'The real tortures of a Chinese prison are the filthy dens in which the unfortunate victims were confined, the stench in which they have to draw breath, the fetters and manacles by which they are secured, the absolute insufficiency even of the disgusting rations doled out to them'; Giles, Glossary,* p. 155. On the other hand, sixteenth century European jails were little (if at all) better in many respects, and is noteworthy that Pereira does not write of his experiences in an embittered tone.

{11} [CRB, p.19, n.2] Theoretically, capital punishment could only be inflicted at the annual autumn assizes, after confirmation of the death-sentence had been received from Peking. · This practice dated from the reign of the first emperor of the Sung· dynasty. In the nineteenth century, the provincial authorities were allowed more latitude. Cf. Ming-shih, · chüan·94; Staunton, Penal Code of China, pp.451-152, 460; Chinese Repository,* IV, 174; China-Review,* II, 173-175; XIII, 401; Gray, China, I, 31-32.

{12} [CRB, p.23, n. l] Parthianous (Japain), Partilõs (Ajuda). Probably derived from the colloquial Put'ing, • (Pö-thian in the Amoy vernacular), district police-masters and jail-wardens. Cf. Carstairs Douglas, Dictionary,* pp.379, 551, and Mayers, Chinese Government,* nr:294.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Galiote Pereira's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, p.65.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics《" "》-- unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated -- followed by the spelling of Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation [CBR], indicated immediately after, between quotation marks within parentheses《("") 》.

1 The author openly praises the Chinese legal system comparing it in laudatory terms with contemporary European justice.

2 "loutea" [original Port.] or 'loutia' [Port.] ("Louteas") = laodie·[Chin.]: literaly meaning, 'venerable father' -- an honourable attribution to high ranking Chinese officials.

3 This statement of the author is justified by the fact that in contemporary Portugal the law ruled the interdiction of corporal punishment to members of certain social classes.

4 "[...] que de maravilha [...]" (lit.: '[...] to marvel [...]" or "[...] what it is a wonder [...]"): meaning, 'dificilmente' ('with great difficulty').

5 This section of the text seems to have been written by the author while still in captivity in China. It is likely that during that time the prisoner might have taken some notes which he used later in the structure of his text. The "sea" thieves mentioned by the author were most probably the wokou: · the multinational -- but mainly Japanese -- pirate groups which assailed the litoral of China throughout the sixteenth century.

6 Another criticism of the Portuguese legal system. The author seems to have been well impressed by the way how the Portuguese prisoners were treated by the Chinese authorities.

7 "moçafo" [original Port.] ("moçafa"): an Arab word which signifies 'book' or 'volume', which in this context, specifically means, The Koran.

8 "brâmane[s]" ("Brahman[s]"): members of a Hindu religious cast who wear a treble band over a shoulder and crosswise on their chest from left to right, which is symbolic of their initiation. Portuguese sixteenth century chroniclers commonly called this band "linha" (lit.: "thread").

9 "Tora" ("Torah"): the Hebrew name of the Pentateuch, the first five books of The Old Testament, whose authorship was often ascribed to Moses.

10 "gentilidade" [original Port.] or 'gentio[s]' [Port.] ("[...] the rest [...]"): all those who did not follow any of the major three monotheist religions: Christianism, Islamism and Judaism.

11 "[...] se [se] encontram [...]" ('[...] say the contrary of what have previously stated [...]'): meaning, 'se se contradizem' ('contradict themselves' or "[...] in any point disagree [...]").

12 "sofrido[s]" (lit.: 'suffered' or 'endured'): meaning, 'tolerantes' ('tolerant') or 'pacientes' ("patient").

13 The author has a positive understanding of the values of Chinese civilization, solely placing religious restrictions regarding the anthropological level of equality between the Chinese and the Portuguese.

14 The author refers to the imprisonement by the Chinese of the Portuguese crew on board of Diogo Pereira's junks, under suspition of their being a group of sea pirates. By inference the author is also making reference to the subsequent Chinese legal proceedings which concluded by recognizing the good intentions of most of the Portuguese.

15 Particularly the Viceroy Zhu Wan, · the principal responsible for the arrest of the Portuguese, who later commited suicide after being accused of abusing his authority.

16 "[...] sem língua, [...]" (lit.: '[...] without tongue, [...]' or "[...] ignorant of that country language [...]"): meaning, 'sem intérprete' ('without an interpreter').

17 The outcome of a complex judicial process was the acquital of the crimes of piracy which the Portuguese had initially been accused of with the Chinese officers reponsible for the Portuguese's imprisonement and false charges being sentenced heavy penalties by the Imperial Commission in charge of investigating the whole affair.

18 "tronco" (lit.: 'trunk' or 'stock'): meaning, 'prisão' ('prison').

19 "[...] pelo pescoço." ('[...] at neck height.' or "[...] standeth up behind the neck."). This was certainly a mistake of the copyist, and it should read 'pelos joelhos.' {sic} ('at knee height').

20 "tábua" [original Port.] (lit.: "board") or 'cangue' [Port.] ('cang'): one of the oldest European descriptions of this Chinese instrument of torture ["portable pillory"]. It is unlikely that the etymon of this word derives from the Portuguese 'canga de bois' ('oxen's yoke'), its most probable origin being the Annamite word 'gang'.

21 "tarfu"· [original Port.] or"taissu" [other Portuguese contemporary chronicles] ("Taissu") = taishi·[Chin.]: most probably, a director of the Imperial prisons of a Chinese province.

22 "chaém" [original Port.] ("Chaem") = chayuan [Chin.]: an itinerant Imperial censor invested with the functions of Imperial commissioner during his obligatory yearly inspection rounds to a number of the country's provinces.

23 "portoão[s]"·[original Port.] ("Parthion[s]") = buding·[Chin.]: probably, a Southern China colloquial name for local police officers or prison guards.

24 "[...] sem nenhuma prisão." ('[...] without the slightest hindrance.' or "[...] that go at liberty."): meaning, 'sem ferros nos pés ou mãos' ('without having their hands and feet chained').

25 "crasta" [original Port.]: might be a mistake of the copyist, and it should read 'claustro' ("cloister").

26 "bailéu" ({not translated}): a movable wooden platform.

27 It was common friends and relatives of the prisoners to keep them alive by bribing the prisons officers and staff.

start p. 69

end p.