As the Governor of {the Portuguese State of} [India] was not providing for the embassy needs and delayed in sending the elephants and horses requested by the ambassador, 1and {above all}* had discharged the Captain-Major Diogo Pereira, 2such matters caused great harm to the offices of God {Our Lord} and His Majesty. But from a certain time onwards he attended to all with greater desire and willingness for the sake of the success of the embassy, not only contributing from his income to pay its expenses but liberaly partaking from it in donations and presents which he sent to the grandees of Guangzhou, • which is a usage amongst the Chinese to speed up matters favourably, as they are an intensely covetous and greedy people ({an usage} which we {the Portuguese} do not repudiate). Such practises gave rise to such casualness from the grandees, daring an unheard of thing never before occured in China: to request the assistance of the Portuguese in the fight against a number of wild thieves. I will write about this in this second part of my Commentaries, thus expanding this narrative of mine. And the events happened in the following way:

There was a certain war commander and great mandarin who was in charged of a mighty fleet belonging to the king [of China]. {That fleet was composed by} eighteen junks - which are as imposing and portentuous vessels as our own - besides a number of other smaller and lighter vessels. Coming from the coast of Chincheo,• 3 {the great mandarin} arrived with his armada in Guangzhou,• crowned with the glory and fortune of having defeated his ennemies. And upon arriving there he requested from the grandees of Guangzhou pay for his men, as they had not been paid for long, being no longer able to subsidise such arrears himself. The grandees delayed the matter for a few days engrossing him in verbal exchanges and afterwards implicating him in a number of misdoings, 4all with the intent of cancelling the requested silver payment. {Finally }, as they were much in fear of him they ordered him to return to Chincheo, leaving his brother behind, { promising him that he} would soon join him with all the requested silver. Trusting their words he did as was told but after his departure {the grandees } had the brother flogged, which was a common practise amongst the Chinese. 5

Having found out about the insult to his brother, the mandarim sailed back with his fleet and, to redress such offense together with the non payement of the silver which was due, he rampaged all his men through the town, killing and ravaging all and everyone, stealing as much as they could get their hands on. It is said that all this happened so suddenly and unexpectedly that in an attempt to escape the robbers, the grandees, their families and staff, and the people {of Guangzhou} rushed through the gates of the walled city {in such panic that} more than two thousand souls died either by drowning {in the moats} or being trampled over. And this is not exageration because the {walled in} city centre of Guangzhou has more people than {the whole of}Lisbon, and all those who visit it agree that it is indeed much larger, most of its population living in suburbia. {The Chinese} are an effeminate and weak people and the fact that they are not allowed to carry or own weapons makes them even more cowardly. 6 So being, the robbers, used to war and having plenty of arms and artillery on their vessels, were able to plunder the whole of Guangzhou without confrontation, not having penetrated into the city walls {compound} because of their massiveness and height.

And after such deeds, they openly declared themselves as robbers and corsairs, endeavouring henceforth to be more and more powerful, equipping themselves with artillery and bellic equipment so that no other powerful fleet might destroy them. In order to secure their protection and safety they chose {for headquarters} the mighty and old city of Dongguan, ·7 which they fortified, and where they relaxed and restored themselves from the hardships of the sea. This city being [a] day away from Guangzhou, every time the robbers wished to assault Guangzhou they withdrew {afterwards} to Tancoan without the slightest hindrance, and in so doing, all those who lived in {the Guangzhou's} suburbs and most of its merchants to leave and move inland, the whole population of Guangzhou going about so frightened and agitated that they prefered to abandon their business than to lose their lives.

But such victories made these robbers even more audacious, thinking that they could disembark at night to our settlement, burn the houses, steal and kill the Portuguese so that after they could be able to pray on and rout our vessels and junks which arrive at [Macao] with the moonson from India and all other regions.

CHAPTER 5

How in mid June the robbers ventured to the Portuguese settlement and, subrepticiously, {attempted to} set foot ashore

By the middle of June, at the arrival time of the vessels belonging to the Portuguese at the aforesaid harbour from various regions, the robbers came too. It was in the afternoon, {when they} entered the anchorage very close to the shore, nearing the western side of the settlement. And when they appeared all the people rushed to the beach to see them, they did not carry their weapons because, being daylight, they knew that {the robbers} would not come ashore. The robbers remained very quiet and tranquil as if in their own land, harbour and city, not displaying in the slightest their resolutions or sending any message stating their intentions. Faced with such nonchalance the Captain-{Major of Macao} gave order for a falcão pedreiro9 to be set on a hillock right before them and to ask them about their intentions. But not even the many shots of ammunitions with which the falcão threatened their junks, intimidated them to depart or budge in any way, as if the connonade had not disturbed them in the slightest. The morning of the following day they raised anchor and left towards the high seas, halting with the greatest of confidence between two of our vessels berthed in the middle of the robbers' waterway, which were about to depart for Japan. And despite the heavy gunfire of the vessels nevertheless the junks meandered between them and continued towards the high sea.

It was immediately understood that the robbers' intension was to stay put at the bar waiting the arrival of unsuspecting junks and {Portuguese}, vessels. Their designs were made clear when they charged over Luís de Melo's10 vessel moored at Langbai'ao, ·its heavy artillery safeguarding it from their assault. And giving up such prey, {the robbers} returned to the bar of our harbour, confident that the vessels coming into the Portuguese harbour would be easier prey. Thus, while maintaining their position at the mouth of the sea, approached a junk belonging to Pêro Veloso, a Portuguese from Malacca married to a native, arrived from Timor, loaded with sandal. 11 And within everyone's sight who were helpless to be of any assistance, the {roobers} invaded upon it and would have captured it if Dom João Pereira's vessel had not lagged behind and remained at bay waiting for high tide.

Becoming despondent with such a reinforcement the robbers {finally} decided to give up capturing Portuguese vessels, also due to the strong defenses they had previously encountered. And thus disappointed they sailed to Guangzhou to get compensation for the losses we had inflicted on them, but the {later} division of these spoils gave rise to such dispute and contention that they split into two groups. And so divided, nine of {their} junks returned to Fujian • while the other nine remained on the side of the mandarin, the ruler of the city of Dongguan. • From there they repeatedly tormented Guangzhou, helpless to oppose them, thus inflicting great losses to the traders incapable to ship their merchandise {downriver} to the Portuguese {in Macao}, where the same was happening to them due to not being supplied with their produce.

The restless boldness of Diogo Pereira saw in this an opportunity to turn this adversity to our advantage and {conceived that, in capturing the robbers, the Portuguese would gain the good graces of} the grandees of Guangzhou. Thus he approached {the grandees} in the name of the king of Portugal and his embassador, offering them all possible assistance and any support they might deem necessary from the Portuguese in order to crush the robbers. And he dealt with such diligence and secrecy that no one became aware of this offer nor of the speculations that were brooding in Guangzhou about the aforesaid assistance; first because he knew that the Chinese would never openly acknowledge their weakness to the Portuguese, and {secondly} because {he knew} that {the Chinese} would never entirely trust {the Portuguese}-- such was Diogo Pereira's instintcs derived from the experience of his {past} dealings with them {i. e., the Chinese}.

However, pleased God that {the Chinese} soon decided it would be a good thing to accept such assistance, and the one to acquiesce was the chong-bing, • captain general of the armies of all provinces in China, second in command only after His Majesty, 13 who, holding such a high rank, was not to be contradicted by the grandees. The chong-bing promptly sent a message to both the embassador and Diogo Pereira stating that he accepted their offer of assistance and that in doing so the ambassador was rendering a great service to the king of China and he added, that he promised he would remain in charge of the expenses of the embassy and would convey them to the king. Also that, meanwhile {the embassador} was to rest in Macao from all the hardships of his long travels. He further requested him to assist and protect the simple people of the {country} villages, to prevent any conflicts that his Portuguese might eventually provoke, such being foremost in the mind of the king {of China} and expected of foreign embassadors of unknown kingdoms. And together with these words were many others of thanks and friendly salutations.

CHAPTER 6

How the chong-bing send a high {ranking} mandarin with the request for assistance accompanied by many vessels to the settlement of Macao and what was decided in it {i. e., in Macao}

Upon receiving the message brought from Guangzhou by Tomé Pereira and being told of the secret dealings he had prepared, Diogo Pereira and the embassador could hardly contain themselves from expressing their alarm but refrained from conveing it to the Captain-Major, not admitting the possibility of the Chinese had surrendered {the Portuguese} with their credit and word of honour. And because the said Tomé Pereira, interpreter15 and servant of Diogo Pereira, had left for Guangzhou without his consent {i. e., of Dom João [Pereira]}, he strongly reprimanded him letting him know that was he to return to Guangzhou without his or the embassador's permission, he would have his ears cut off. Asked if he had brought a message from the chong-bing regarding ambassadorial matters with him, Tomé Pereira replied 'yes' to the great laughter and derison of Dom João, who had been {previously} informed that the grandees were not prepared either to recognize or to receive the embassy. Diogo Pereira, being a discreet person, hid all and feigned nothing, remaining as faithful to Dom João has he had always been, thus obliging the offices of God {Our Lord} and His Majesty.

And at that very moment the mandarin arrived at the Macao harbour accompanied by junks and Lanteaas, • sent by the chong-bing with the request for assistance. The mandarin charged of delivering it was one of great authority and honour. Having once been a high commander of the army he was at present out of grace of the king [of China] for the poor results at war, but the chong-bing, holding him in great esteem, still distinguished him in all his actions so that through his renewed endeavours he {i. e., the chong-bing} would be able to highly commend him to the king [of China] thus redeeming him from his {unfavourable} position and enabling him to regain {lost} graces. And althought this should not concern us, we would certainly please God greatly if we stopped withdrawing honour and merit from the real authors of good services attributing them to ourselves, as is done daily.

Upon arriving, the mandarin's pomp and demeanour, and the powers with which he had been invested, attested for his seriousness and valour he had manifested in the past. He immediately sent word of his arrival to the ambassador and Diogo Pereira, requesting a meeting at a place of their choice so that he might convey them the matter which had brought him {to Macao}. {The ambassador and Diogo Pereira} promptly sent their jurubassas16- the interpreters who speak the local dialect- to receive him and welcome him. Now, regarding the selection of the meeting place, he [Diogo Pereira] conveyed {to the mandarin} that he was no longer the Captain-Major, this post being now occupied by his successor Dom João Pereira. And because it was practise among the Portuguese to be subordinate in all things to their Captain-Major, he begged him {i. e., the mandarin} to enquire from him {i. e., Dom João Pereira} the locality {of the meeting} requesting him {i. e., the Captain-Major} to pay him {i. e., the mandarin} a visit and to let him know of his arrival and the purpose of his [stay]. And that he {i. e., Diogo Pereira} and the ambassador were at his entire disposal for anything else he might deem necessary, also that they would all meet in due time. Having received the message the mandarin immediately sent word {of his arrival} to Dom João Pereira who promptly sent for the ambassador and Diogo Pereira, as well as his brother Guilherme Pereira and Luís de Melo, and many other lords and His Majesty's officers. Having agreed assist them as requested, they set to making preparations immediately. The assembly took place on the morning of St. Cosmo's day, in the year of 1546.

CHAPTER 7

The matter decided at the council held in the house of Dom João Pereira and concerning [his] meeting with [the] mandarin at the Chinese Temple

After the mass the Captain-Major retired to his residence together with many fidalgos and important members of the settlement in order to hold council {regarding} the visit of the mandarin and the assistance which he had requested. The people who sat at this council were: The reverend Father João Soares, Procurator and General Visitor of the China mission, the ambassador [Luís de Góis], Luís de Melo, Diogo Pereira and his brother Guilherme Pereira, Dom Manuel de Castro, Jorge Ribeiro Manojo, Henrique Fernandes Nordelo, Gaspar da Nóbrega, and other lords. 18 And being all assembled, the Captain-Major took the floor {and explained} that the mandarin had been sent by the chong-bing to request his assistance against the robbers, this being the reason why he has gathered Your Graces. They were to express their feelings {on this issue} and what would be decided there and then was to be firmly implemented, his being confident that all present would not only perform their duty - particularly bearing in mind that there were at the service of God {Our Lord} and His Majesty - but also contribute with men and moneys towards providing the requested assistance - because there was no purveyance of His Majesty {the king of Portugal, in Macao}. All present cheered these words unanimously and in unisson, and said that it was indeed very pressing to give assistance, not only for the good offices of God {Our Lord} and His Majesty but for the sake of all. And because the robbers were on the rampage {assistance should be provided} without delay, in the expectation that such a gesture would achieve much agreement and friendship {between the Portuguese of Macao and the authorities of Guangzhou} in perpetuity and without it discord would arise and the embassy would have no chance of being received {by the 'king' of China}. Many other {reasons} besides were given in favour of providing assistance, such as to prove that the Portuguese were not villains and thieves - as most Chinese presumed- but a people of great trust and integrity, the proof of this being the willingness they were now showing in offering their lives and belongings.

So, all agreeing in this issue, Dom João said that he would meet the mandarin that same afternoon and would let him know that in the name of His Majesty and His ambassador, he could count on assistance {from the Portuguese of Macao}, and what would be then discussed would be established later with the Portuguese in the best possible way. [...]

So being, the mandarin sent word to Dom João that he would disembark and go to the Chinese temple19 where he would be expecting him. Would His Lordship please make haste to the meeting point, so that they could come to terms without delay. Dom João agreed and went to the prescribed place which is within the confines of the settlement, which was by the sea front. He arrived accompanied not only by many members of his household but also important dignataries of the settlement, all attired in satins, kermes cloths and velvets apparelled with gold and finery. Dom João was dressed in the French fashion with a fulvous satin gallonned with gold, 20 some breeches and a waistcoat of the same [material] a velvet beret with an oppulent medallion, and a two-string gold necklace. He was wearing the richly enamelled badge of honour of the Order of Christ attached to its diagonal ribbon. His personal attendants wore shinny fulvous satin garnments, one of them carrying a precious gold rapier. [Dom João] arrived at the Chinese temple before the mandarin and waited (but not for long) seated on a brocade chair laid over a valuable campaign rug, no shade to be had besides that provided by the standing parasols. From far off it was a spectacle as of a splendid army encampment.

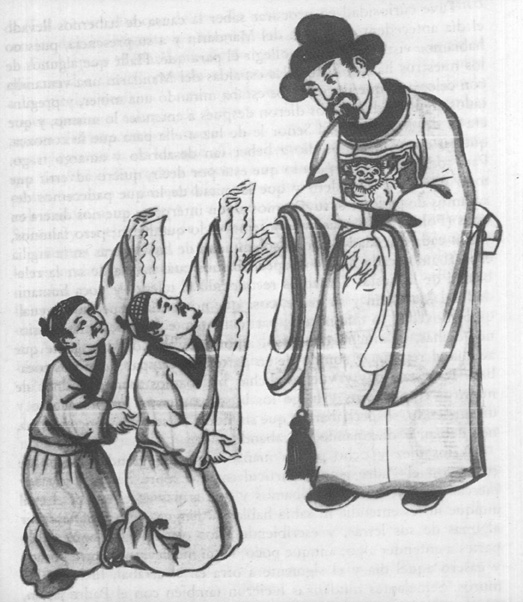

A mandarin's audience.

In: CORTES, Adriano de las, S. J., REBOLLO, Beatriz Moncó, intro. and annot., Viaje de la China, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, p. 118.

CHAPTER 8

The pomp of the mandarin's retinue and what went between Dom João and he

As soon as the mandarim saw the Captain-Major arriving at the Chinese temple he came to meet him, leaving the junk where he was. And as he sailed ashore they rang out many talicos, 22 which are like our cymbals and a variant from kattledrums, like those announcing the end of Carnival. Another novel instrument announcing him {i. e., the mandarin} was {played} like a pipe or a bombardon. He set foot ashore preceded by ten or twelve standardbearers, each holding a flagpole with a blue taffeta ensign with a centred device written in bold lettering. After these came some attendants carrying staffs like cannons' but made {entirely} of metal. Following these came others holding tablets and some poles set on metal and others wearing more strangely an 'invention' of silk {embroidered with} gold {tread} resembling short dalmatics over swaddling-bands made of another curious silk. They wore helmets, with pigtail of finely groomed hair on their backs hanging from one of their extremeties, together with other peculiarities which cannot be described for lack of {appropriate} words.

After these came many civil officers, 23 which are like baillif officials, holding thick bamboos, which are like reeds of a palm split in half in diametre. With these they flog {the culprits} and give justice. These were followed by the mandarin's pages carrying his betel boxes and tea caddies, 25 together with others holding fans with which they winnowed him. The mandarin was in an unusual sedan chair carried on Chinamen's shoulders under a parasol of yellow taffeta which is the emblematic colour of officers of the royal household. This honour and excellence is conferred on them exclusively, and no others, thus making the high rank of its bearer known. He {i. e., the mandarin} wore wide and long profusedly pleated surplices of a light rouge damask of liquid transparency with a pectoral of silver and shells which looked like a horse's harness, all extremely loose fitting. Such attire was worn for the sole purpose of expliciting his status, much like any other dignatary. On his head rested a black forelock, like the Romans used to wear, framed by extremely bizarre gold panels. The said forelock is equally an exclusive insignia of a high ranking mandarin. His {headgear} was destitute of the {lateral} flaps worn by other mandarins indicating that he was a civil {i. e., not military} government officer. 26 His demeanour and countenance were extremely grave, his stature straight and his face broad, in much resembling Dom Constantino. 27

Being transported in such a way to where Dom João was, he steped out of the {sedan} chair and walked towards him, and Dom João rose and went to welcome him. After ceremonious courtesies in the Chinese manner they sat down. And to our jurubassas - who acted as translators kneeling before him - he delivered the following speech: "I came to this settlement as an emissary of the chong-bing, the head mandarin for the government's military affairs of all the provinces of China. {I came} to request assistance to the embassador of the king of the Portuguese and his Captain-Major, trusting that they would attend such just and needed request, being against the robbers who had destroyed Guangzhou and stopped the flow of goods and which prevents the traders {to do their business}. But above all, what prompted the chong-bing to sent me here was that he was first addressed to do so by the ambassador {of the king of Portugal}.

Also, believing that it would be easier to trap and capture the robbers in their own nest, and knowing that they are now moored in the bay of Dongguan, the said merchants pleaded the chong-bing to deliver them from such calamity.

And in order to prevent them {i. e., the robbers} from being alerted of this war strategy I already brought with me all the necessary ships, so that all those who will join either fleet - be it the one who converges on them from high sea or the one from the shore line - make haste to set sail."

To this Dom João repplied that him and the Portuguese already for a long time had been repeatedly offering whatever they {i. e., the Chinese authorities} might require from them, being anxiously waiting the moment when China would express its wants and grant them the opportunity to serve the king of China, in manpower as well as in goods or moneys. And this out of the great respect the Portuguese have for them and for the government authorities of their king. That it was costumary from the Portuguese never to deny support and assistance to those who requested it, much less to such a just and imperious cause that- besides all other {possible} reasons - compelled a person in his post {of Captain-Major} to attend to it. Over and above he spoke {to the mandarin} words of great favour and friendship, elating his pride and judgement, whom being greatly pleased, praised the Captain {-Major for them} highly.

And thanking him such good willingness, he {i. e., the mandarin} promptly inquired if the chief captain of the assisting forces was present, and if he was to make himself known, as he had a silver credential tablet for him from the chong-bing and others for the captains of all the other ships accompanying him. Dom João introduced Dom Manuel [de Castro] letting him know that he would be the chief captain {of the expedition}. 28 And so, the mandarin gave him a silver credential tablet and finding him young, turned to Dom João and warned him that he was not to judge lightly the enormity of the assistance that he {i. e., the mandarin} was requesting, and that the vessels of the robbers were nine and very large, {equipped} with plenty of cannons and ammunitions of war. {And that besides these} there were others not so big, and more than two thousand fighting men well provided with many weapons, saligues, 29and sharply pointed iron stakes {which they use in} sea assaults. To what Dom João repplied that he quite wished they {i. e., the robbers} were even mightier and that a hundred Portuguese were enough to deal with such a number in half an hour, but just to reassure him {i. e., the mandarim} he would send two hundred, which were plenty for the {Chinese} fleet of two hundred junks. {And that the mandarin} should not express surprise at his words so full of confidence, because he was speaking as a veteran captain well experienced in warfare, having long served in the armies of His Majesty, and having gained much practise during his captainship of Malacca. The mandarin felt slightly more confident, but the little knowledge he had of the Portuguese did not reassure him of {Dom João's} words of promise. Nonetheless, he was deferential, and because it was getting late in the day, it was thought best to retire, and it was settled that the said assistance would be provided and with the greatest possible haste. So being, and because he sojourned on board, the mandarin went back to the boat who had brought him ashore, and Dom João Pereira returned home; all others remaining commited to their previous appointments.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Fiona Clark

For the Portuguese text, see:

ESCOBAR, João de, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Informação da China, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica d o s Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.68-74 -For the Portuguese modernised version by the author of the original text, with words or expressions in square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese text, see:

LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, Em Busca das Origens de Macau, Lisboa, Grupo de Trabalho do Ministério da Educação para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses [Work Group from the Ministry of Education for the Commemoration of the Portuguese Discoveries], 1996, pp. 149-157 - Partial translation.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in João de Escobar's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.73-74.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics « " "» - unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated.

1 The embassador Gil de Góis had requested two elephants from the [Portuguese] State of India to be included in the list of gifts to the Emperor of China. He expected this exotic present to accrue the credibility to the Portuguese embassy.

2 Diogo Pereira was Captain-Major of Macao until the arrival of Dom João Pereira at the territory in 1564, the new recipient of the post automatically being granted with the royal concession of a 'Japan voyage'. Diogo Pereira was one of the wealthiest Portuguese merchants trading in the Far East having interests in Macao since the early days of its settlement. (See: Text 9 - João de Barros)

3 "Chincheu"·[Port.] ("Chincheo") = Fujian· [Chin.]: meaning in this context, the coast of this province and more specifically, the region of Xiamen· Bay [Bay of Amoy] near the city of Zhangzhou,· frequently assailed those days by the wokou, · the multinational - but mainly Japanese- pirate groups which assailed the litoral of China throughout the sixteenth century.

4 "impunham"('imposed'): meaning in this context 'imputavam' ("imputing").

5 Many coeval Portuguese texts describe the Chinese practise of flogging criminals with bamboo canes in considerable detail. (See: Text 9 - João de Barros)

6 Extracts of several texts assembled in this Documental Anthology -"Review of Culture" issues nos32 and 33 - repeatedly mention this apparently debilitating characteristic of the Chinese men, although such judgement was only applicable to the common people.

7 "Tancoão"·[Port.] ("Dongguan") =Dongguan[Chin.]: a location about ten leagues west of Guangzhou. ·

8 Macao did not have a steady number of residents all year round. Although the text states that in 1564 there were three hundred residents in the city, this number was to become considerably larger during the peak of the sea trade season.

9 "falcão pedreiro"[original Port.] ("falcão pedreiro"): a contemporary small cannon able to throw stone balls.

10 Luís de Melo Pereira, who had been granted the royal concession of a 'Japan voyage' had just arrived at the coast of China from Java [presently Jawa] loaded with a precious cargo of pepper.

11 The Portuguese first set foot in the Island of Timor around 1515, with the intention to purchase white sandalwood to be transported and traded in China. This extremely aromatic wood was in great demand in China for the making of furniture and as an ingredient of insense, burnt in quantities by the people during their daily religious practises.

12 "[...] tomaram-no [...]"('captured it'): should read 'têlo-iam tornado'("[...] would have captured it [...]").

13 The author makes a confusion between ranks. "chumbim"·[Port.] ("chong-bing") = zongbing·[Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's armed forces.

14 Tomé Pereira was a Chinese who had acquired Portuguese manners and an attendant of Diogo Pereira.

15 "[...] a língua [...]"(lit.: 'the tongue'): meaning in this context, an 'intérprete'("interpreter").

16 "jerubaça"[original Port.] or jurubaça' [Port.] ("jurubassa"): a term of Malay origin which means 'an interpreter'.

17 "dia dos Cosmos"(lit.: 'day of the Cosmos'): possibly meaning, the dia de S. Cosme'(" [...] St. Cosme's day, [...]").

18 These would undoubtedly be the most important residents of Macao.

19 "varela" [original Port.] ("[...] Chinese temple [...]"): a pagoda or a Buddhist temple.

20 "atorcelar"[original Port.] ("[..] gallooned with gold [..]"): to embellish costumes and apparel with torsels of silk and gold or silver thread akin to the treble band worn by the Brahmans over a shoulder and crosswiseon their chest from left to right, symbolic of their initiation.

21 The author makes reference to the way how the ribbon and badge of honour of the Order of Christ are to be worn.

22 "talico[s]"[original Port.] ("talico[s]"): an undecipherable Chinese term which does not reappear in any other Portuguese contemporary text.

23 "upo[s]"·[Port.] ("civil officer") = dubo• [Chin.]: a bailiff's official.

24 "bétele"("betel"): a chewing mixture of pounced arecanuts, lime, oyster powder and other aromatic substances roled in a betel leaf, with stimulating and astrigent properties much appreciated in the Far East. Most historians seriously question the verity of being also taken by the mandarins [Chinese government officials], during the sixteenth century.

25 "chaa"·[original Port. [ ("tea") = cha·[Chin.]. Notwithstanding previous narratives of Portuguese visitors to Japan having already mentioned this typical Oriental beverage, the author's is the first to directly incorporate its Chinese terminology. A few years later, in 1569-1570, Friar Gaspar da Cruz would write in chapter thirteen of the Evora edition of his Tratado das Cousas da China [...] (Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]) of "[...] a tepid water which they call chá (tea) [...]."

26 The rank of a mandarin [Chinese government official] could be identified by the insignia worn in his garnments and a number of qualifying attributes, such as his pectoral, his hat and its distinctive lateral flaps, his parasol, a prescribed number of attendants, etc. - which varied according to status within the official hierarchy. Mandarins were, in principle, civil servants who had successfully passed at least one of the three increasingly difficult official Imperial examinations, comparable, in a basic way, to the present Western degrees of Baccalaureate or Bachelor's, Litentiateship or Master's and Doctorate or Doctor of Philosophy. Certain military functions could be attributed to low rank mandarins, which might explain why the hat of the mandarin who visited Macao was deprived from its traditionally prescribed flaps.

27 The author apparently found some similarities in between the traits of the Chinese mandarin and those of Dom Constantino de Bragança, the for Wmer Viceroy of the [Portuguese] State of India, from 1558-1561.

28 At a later date Dom João Pereira was to nominate Luís Pereira de Melo as chief-captain of the Portuguese contingent, a choice prompted by the popularity he held among the Macao residents. Despite his high social status Dom Manuel de Castro might not have the ideal profile to impose due respect and enforce the necessary discipline to rough but experience sailors of the China seas.

29 "saligue[s]"[original Port.]("saligue[s]"): contemporary military hurling weapon.

*Translator's note: Words or expressions between curly brackets occur only in the English translation.

start p. 87

end p.