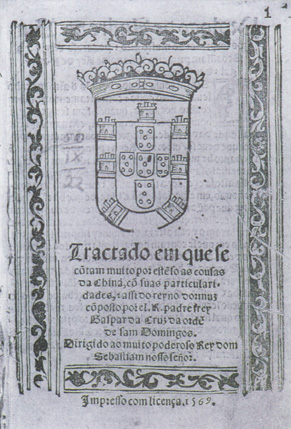

Frontespiece.

Because we spake so many times of Portugal captives in China, 1 it will be a convenient thing that the cause of their captivity be known, where many notable things will be showed. You must know that from the year 1554 hitherto, the businesses in China are done very quietly and without danger; and since that time till this day there hath not one ship been lost but by some mischance, having lost in times past many.

Because as the Portugals and the Chinas were almost at wars, when the China fleets came upon them, the Portugal ships weighed anchor and put out to sea, and lay in places unsheltered from tempests, whereby the storms coming, many were lost upon the coast or upon some banks. 2

But from the year 1554 hitherto, Leonel de Sousa (born in Algarve, and married in Chaul) being Captain-Major, made a covenant with the Chinas that we would pay their duties, and that they should suffer us to do business in their ports. {1}3 And since that time we do them in Cantão ·which is the first port of China: and thither the Chinas do resort with their silks and musk, which are the principal goods the Portugals do buy in China. There they have sure havens, where they are quiet without danger, or any one disquieting them, and so the Chinas do now make their merchandise well: and now both great and small are glad with the traffic of the Portugals and the fame of them runneth through all China. Whereby some of the principal persons of the Court come to Cantão only for to see them, having heard the fame of them. Before the time aforesaid, and after the rising which Fernão Peres de Andrade4did cause, {2} the business were done with great trouble; they suffered not a Portugal in the country, and for great hatred and loathing called them Fancui, ·{3} that is to say 'men of devil'.5

Now they hold not commerce with us under the name of Portugal, neither went this name to the Court when we agreed to pau customs; but under the name of Fangim ,• {4}6 which is to say 'people of another coast'. Note also, that the law in China is that no man of China do sail out of the realm of pain of death. {5} It is only lawful for him to sail along the coast of the same China. And yet along the coast, nor from one place to another in China itself, is it lawful for him to go without a certificate of the Louthias •7 of the district whence he departeth; in which is set down, whither he goeth, and wherefore, and the marks of his person, and his age. 8 If he carrieth not this certificate he is banished to the frontier regions. The merchant that carrieth a certificate of the goods he carrieth, and now he paid duties for them. In every custom-house that is in every province he payeth certain duties, and not paying them he loseth the goods, and is banished to the frontier parts.

Notwithstanding the abovesaid laws some Chinas do not leave going out of China to traffic, but these never return again to China. Of these some live in Malacca {presently Melaka}, other in Sião {Siam, presently Thailand}, others in Patane, and so in diverse parts of the South9 some of these that go without licence are scattered. Whereby some of these who live already out of China do return again in their ships unto China, under the protection of the Portugals; and when they are so dispatch the duties of their ships they take some Portugal their friend to whom they give some bribe, that they dispatch it in his name and pay the duties.

Some Chinas desiring to get their living, do go very secretly in these ships of the Chinas to traffic abroad, and return very secretly, that it be not known, no not to his kindred, that it be not spread abroad and they incur the penalty that the like do incur. This law was made because the King of China found that the frequent communication with foreigners might be the cause of some risings, and because many Chinas on the pretext of sailing abroad became pirates and robbed the districts along the sea coast.

Yet for all this diligence there are many China pirates along the sea coast. These Chinas that live out of China, and do go thither with the Portugals since the offence of Fernão Peres de Andrade{6}10 did direct the Portugals to begin to go to trade to Liampoo •{7}11 for in those parts there are no walled cities nor villages, but many and great towns along the coast, of poor people, who were very glad of the Portuguese, and sold them their provisions whereof they made their gain. {8} In these towns were those China merchants who came with the Portugals, and because they were known, for their sakes the Portugals were the better entertained, and through them it was arranged for the local merchants to bring their goods for sale to the Portugals. And as these Chinas who came with the Portugals were the intermediaries12 between the Portugals and the local merchants, they reaped a great profit thereby.

The inferior Louthias of the sea coast received also great profit of this traffic, for they received great bribes from the one and from the other, to give them leave to traffic, and to let them carry and transport their goods. {9} So that this traffic was among them a long while concealed from the King and from the superior Louthias of the province.

After these matters had for some space been done secretely in Liampoo, the Portugals went forward little by little, and began to go and make their merchandise at Chincheo·{10}13 and in the islands of Cantão. {11}14 And other Louthias permitted them already in every place for the bribes sake, wherevby some Portugals came to traffic beyong Namqui· {12}15 which is very far from Cantão, without the King ever being witting, or having knowledge of this traffic. 16 The business fell out in such sort, that the Portugals began to winter in the islands of Liampoo{13}17 and when they were so firmly settled there and with such freedom, that nothing was lacking them save having a gallows and pelourinho. {14}18 The Chinas who accompanied the Portugals, and some Portugals with them, came to disorder themselves in such a manner that they began to make great thefts and robberies, and killed some of the people. These evils increased so much and the clamour of the injured was so great, that it came not only to the superior Louthias of the province but also to the King. 19 Who commanded presently to make a very great armada in the province of Fuquẽ·{15} to drive the pirates from all the coast, especially those that were about in Liampoo; and all the merchants, as well Portugals as Chinas, were included in this number of pirates. 20

The armada being ready, it put forth to cruise along the sea coast. And because the winds served them not then for to go as far as Liampoo, they went to the coast of Chincheo, where finding some ships of the Portugals, they began to fight with them, and in no wise did they permit any wares to come to the Portugals, 21 who stayed many days there (fighting sometimes) to see if they could have any remedy for to dispatch their business, But after many days had passed, and seeing that they had no remedy they determined to go without it. The captains of the armada knowing this, sent a message to them very secretly by night, that if they would that any goods should come to them, that they should send them something. The Portugals were very glad with this message, prepared a great and sumptuous present, and sent it by night because they were so advised. From thence forward came many goods unto them, the Louthias making as though they took no heed thereof, and dissembling with the merchants. And thus in this way was done the trade for that year, which was the year of 1548. {16}

CHAPTER XXIV

How the Chinas armed against the Portugals, and of what followed from this armada.

The year following, which was 1549, there was a straighter watch upon the coast by the captains of the armada, and greater vigilance in the ports and entrances in China, in such sort that neither goods nor victuals come to the Portugals. But for all the vigilance and watching there was, as the islands along the coast are many (for they run in a row along the length of China) the armadas could not have so much vigilance, that some wares were not brought secretly to the Portugals. {17}

But they were not so many that they could make up the ships' landings, and the uttering{18} those goods which they had brought to China. Wherefore they left the goods which they had not uttered in two China junks, of such Chinas as were already dismembered from China, and traffic abroad under the shadow of the Portugals; in the which they left thirty Portugals in charge with the ships and with the goods, that they might defend the ships, and in some port of China where best they could they should sell the goods that remained in exchange for some wares of China, and having ordained this they departed for India. 22

As the people of the China armada saw the two junks remain alone, the other ships being one, they fell upon them, being induced by some merchants of the country, who revealed to them the great store of goods that remained in those junks, and the few Portugals that remained to guard them. They therefore laid an ambush for them, dressing some Chinas ashore, 23 who being in arms made as though they would set upon the ships to fight with them (because they were close to the land), so that the Portugals being provoked should come out of the ships to fight with them, and thus the ships might remain defenceless to them of the armada, which lay close at hand to attack them, concealed behind a promontory which jutted out into the sea. {19} Those who were left to guasrd the junks being provoked in this manner, being heedless of the ambush which they ought to have suspected was laid for them, some of them sailed forth to fight with the Chinas ashore. On seeing this, those of the armada who were watching in ambush, set upon the two junks with great fury and celerity, and slaying some Portugals that they found in them and wounding others, they took the junks.

The chief Captain which is the Luthissi, ·{20}24 remained so vainglorious and so pleased with this victory that it was a wondrous thing to see his joy. And he forthwith used great cruelty on some Chinas whom he took with the Portugals. He laboured to persuade four Portugals who had more appearance in their persons than the rest, that they should say that they were Kings of Malacca. And he persuaded them in the end, because he promised to use them better than the rest, and therewith he introduced them. And finding among the clothes that he took a gown and a cap, and asking one of those Chinas who were taken with the Portugals what habit that was, they put in his head that it was the habit of the Kings of Malacca, wherefore he commanded forthwith to make three gowns by that pattern, and three caps, and so he appareled them all four in one sort, to make his deceit true, and his victory more glorious. To this he joined the covetousness of the Luthissi, to see if he could detain the many goods that he had taken in the junks. In sort that he both wished to triumph over the Kings of Malacca, so that the King might give him great rewards for his service which he wished to show he had done him, as because he wished to help himself to the goods which he had taken, for to make a greater display with them to the people of China of his glorious victory. And in order to do this more safely, and not to be taken in a lie, he did great executions upon the Chinas whom he took with the Portugals, and killing some of them he determined to kill the rest.

Tractado em que ∫e / cõtam muito por e∫tÂ∫fo as cou∫as / da China. cõ ∫uas particulari. / dades, a∫∫i do reyno dormuz / cõpo∫to por el. R. padre frey / Ga∫par da Cruz da ord / de ∫am Domingos. / Dirigido ao muito podero∫o Rey dom / Seba∫tiam no∫∫o ∫eñor./

Impre∫∫o com licená, [Évora, André de Burgos], 1569.

Tractado em que ∫e / cõtam muito por e∫tÂ∫fo as cou∫as / da China. cõ ∫uas particulari. / dades, a∫∫i do reyno dormuz / cõpo∫to por el. R. padre frey / Ga∫par da Cruz da ord / de ∫am Domingos. / Dirigido ao muito podero∫o Rey dom / Seba∫tiam no∫∫o ∫eñor./

Impre∫∫o com licená, [Évora, André de Burgos], 1569.

These things coming to the ears of the Aitão·{21}25 who was his superior, he reproved him severely for what he had done, and sent to him forthwith the he should kill no more of those that remained, 26 but that he should come to see him immediastely, bringing with him all the prize, as well of men that were yet alive, as for the merchandise. The Luthissi ordering his journey for to go to the Aitão as he was commanded, he ordered four chairs to be given to the four whom he had given the title of Kings, to be carried in them with more honour. And the other Portugals were carried in pillory-coops{22} with their heads out fast by the necks between the boards so that they could not pull them in, and those who had some wounds were likewise taken along exposed to the sun and to the open air.

In this manner they took their food and drink, and thus they obeyed the calls of nature, which was no small torment and suffering to them; and they were taken seated in these coops, being carried on men's shoulders. The Luthissi went with this prize through the country with very great majesty, and carried before him four banners displayed, on which were written the names of the four Kings of Malacca. 27 And when he entered into towns, he entered with great noise and majesty, with sound of trumpets, and with criers who went before, proclaiming the great victory which the Luthissi so-and-so had gotten of the four Kings of Malacca. And all the great men of the towns came forth to receive him with great feasts and honours, and all the people came running to see the new victory.

When the Luthissi came with all his pomp and glory where the Aitão28 was, after giving him a particular account of all that had happened and of his victory, he revealed his plan to him and agreed with him to divide the goods between them both, and that he should continue the feigning of the Kings of Malacca, so that both might receive of the King honours and rewards.

This being resolved, they both agreed that to keep this in secret the Luthissi should go forward in that which he had begun, to wit, that all the Chinas who had come there captives should be killed. And forthwith they ordered that it should be put in effect, whereby they killed ninety and more Chinas, among whom were some small boys slain. {23} They left notwithstanding three or four youths and one man, that by them (bringing them to their own hand) they might certify the King all that they would, which was to make out the Portugals as pirates, concealing the goods which they took from them, certifying also by these men that those four Portugals were Kings of Malacca. And the Portugals, not having the language of the country, nor having anyone in that region who could favour or protect them, would perish.

And they being mighty would make their own tale good, following the end of them intended, And for this reason and for greater triumph of the victory, they slew not the Portugals, but left them alive. These Louthias could not do this so secretly, nor in such safety, but that their fraudulent wickedness became known, and were generally reproved of the people. And people of all conditions chiefly reproved the executions and cruelties which they had made, since it is an unusual thing in China to kill anyone without leave of the King, as we have said above. {24} An even in inflicting death sentences the justice of this land is very slow and deliberate, as we have shown above. Besides all this, many of those whom they slew had kindred in that region, who did grieve at the death of theirs.

Whereby, as well by these as by some Louthias who were zealous of justice and would not give consent to such great evils and fraudulent dealings, this matter came to the King's ears, and he was informed how the Portugals were merchants who came to traffic with their merchandise in China, and were not pirates; and how four of them had been given falsely the title of Kings, to the end that the King should show them [i. e. the Aitão and the Luthissi] great favours and do them great honours; and how these two had usurped great store of goods, and that for to conceal these evils they had killed men and children without fault. When the King was informed of this, he was very angry and very grieved thereat, and forthwith he ordered justice to be done in this matter and with great speed and diligence, as can be ssen in the following chapter which gives a full account thereof.

CHAPTER XXV

Of the diligence that was done to find out what sort of people the Portugals were; and how the judicial enquiry was made into their imprisonment.

As soon as the King was informed of all the above-said, he forthwith dispatched from the Court a Quinchay•29 (of whom we spake before, that is to say a 'chop of gold'). {25} And such men, as we said, are never sent on very weighthy affairs. And with him he sent other two men of great authority also, of the which the one had been Ponchassi• and the other Anchassi, •30 these two as inquisitors and examiners of this matter, {26}31commanding and commending to the Chaẽ•{27}32 who that year went to vist the province of Fuquem,• and to the Ponchassi and Anchassiof the same province, their aid and assistance to the Quinchay and to the two inquisitors in all things necessary for them in this business; greatly commending to all concerned in this case that they should investigate the matter as loyal servants and friends of good justice and of the good government of his Kingdom. And as this happened at a time when the provinces were all provided with new officers, all the above persons came together from the Court and they all entered the city of Funcheo• with very great pomp.

And as soon as they arrived, they all began with very great diligence and care to investigate the business on which they came, and which had been so highly commended to them. The two that came with the Quinchay as inquisitors, went forthwith to certain great houses which had in the middest a great courtyard; and on the one side of the court were certain great and fair lodgings, and on the other side others in the same sort. Each of the inquisitors entered in one of these houses aforesaid.

The prisioners were straightaway brought and were presented to one of them. He for courtesy remitted them to another that he should examine them first, with words of great courtesy. The other sent them back again with many thanks. So they were sundry times carried from one to another, each of them willing to give the hand to the other of beginning first, till that one of them yielded and began. And as the matter was of great important and much commended to them, all that the accused and the accusers did speak, these officers did write with their own hands.

The Portugals had for great ennemies a China man and pilot of one of the shipss that were taken, and a China youth who was a Christian, and who from a child was brought up among the Portugals; for they were both made of the part of the contrary Louthias, moved by gifts and promises. The Louthias were already deposed from their offices, and held for guilty of that which they were accused before the King; but though they were thus handled, they were still so mighty and so favoured that they could take from the Portugals a China youth who served them as interpreter, so that the Portugals not having anyone who understood them would not be able o defend justice of their cause. This youth was returned to the Portugals by means of a petition which was drawn up for them by a China prisioner, which they presented to the inquisitors, who when they read it, immediately ordered the youth to be handed over. And this youth was the cause of their deliverance, because as through him they could make themselves understood to the officers of justice, they could prove very well that they were blamless. They examined them in this order.

The accused were first brought and examined by one of those officers, and then they carried them to another to be examined again. And while this other was re-examining the accused, the accusers were brought to him that examined first. And as well the accused as the accusers were all examined by both the officers, that afterward they both seeing the confessions of the one and the other they might see if they did agree. 33 And first they examined everyone by himself. Afterward they examined them altogether, for to see if the one did contrary the Other, or did contend and reprehend one another, that so by little and little they might gather the truth of the case. {28} In these cross-examinations the two were contrary, to wit, the pilot and the Christian China youth, and they were given many stripes because they disagreed in some things.

The Louthias dis always show themselves glad to hear Portugals in their defense, which was a source of great comfort to them. It was also a great help to them that they all spoke through one interpreter and so did not contradict each other. And because the Portugals alledged in their defence, that if they would know who they were, and how they were merchants and not pirates, they should send to enquire of them along the coast of Chincheo, {29}34 and that there they should know the truth, which they might know of the merchants of the country, with whom they had traded for many years: and that from them they would learn that they were no Kings, for Kings do not abase themselves so much as to come with so few men to play the merchant, and if before they said the contrary it was by the deceit of the Luthissi, and to receive better usage of him in their persons.

Having this information of the Portugals, both of the inquisitors went forthwith to Chincheo, with the approval of the Quinchay and other officers, to enquire into the truth of that which the Portugals had told them, nor was this enquiry entrusted to anyone else save only these two persons. As soon as these Louthias had finished making enquiry in Chincheo, since they learnt thereby of the truth of what the Portugals had said, and the lies of the Luthissi and of the Aitão, they dispatched immediately a post wherein they comanded to put the Luthissi and the Aitão in prisons, and in good safeguard. {30}

By this can be seen with how much power these men were invested, since they could arrest such great men; something which aroused wonder in all the country, and many people told the Portugals that they were very lucky, since such great men had been arrested for their sakes. Wherefore from thence forward all men began to favour them very much. Notwithstanding, if this examination had been made at Liampoo{31} instead of at Chincheo, the Portugals could not but have passed it very ill, since the evils which they had done there were great. 35 After the Louthias returned from Chincheo, they commanded to bring the Portugals before them and conforted them very much, showing them great good-will, and telling them that they knew already they were no pirates, but were honest men: and they examined again as well they as their adversaries, to see if they contradicted themselves in any thing of that which before they had spoken.

In these later re-examinations the China pilot, who before had showm himself much against the Portugals, and had been on the Louthias side, seeing that the Louthias were already in prison and that now they could do him no good, and that the Portugals were already favoured and that the truth was already known, he gainsaid himself of all he had said,and stated that it was true that the Portugals were no pirates nor Kings, but were merchants and very good men, and he revealed the good which the Luthissi{32} had taken when he surprised the Portugals. He added that if until then he had maintained the contrary, it was due to the great promises which the Louthias had made him, and for the great threats they had used to him if he did it not. But seeing they were already in prison, and that he knew they could now do him no hurt, he wished now to speak the truth.

This was a thing which made the Louthias greatly to wonder, and they gazed at each other, as if out of their wits, for a great space of time without saying a word. And recollecting themselves, they then commanded to torment him and to whip him very sore, to see if he would gainsay himself, but he still persevered in the same confession.

All the examinations and diligences necessary in this business being ended, the Quinchay willing to depart for the Court with his company, would first see the Portugals and give a sight of himself to the city. The sight was of great majesty in the manner he went abroad in the city, for he went accompanied by all the great men of it, and with many men in arms and many banners displayed and very fair, and with many trumpets and kettle-drums, and many other things which on such occasions and pomps are used. And accompanied in this manner he went to certain very noble and gallant houses. And all the great men taking their leave of him, he commanded the Portugals to come near him, and after a few words he dismissed them, since this was only for to see them.

Before these Louthias departed, they commanded the Louthias of the region, and the jailers, that all of them should favour the Portugals and give them very good entertainment, and should command to give them all things necessary for their persons. And they commanded every one to set his name in a piece of paper, because that while they were going to the Court and dispatching of their business, they should not craftily make some missing. And they commanded to keep the Luthissi and the Aitão{33} in strict custody, and that they should not let them communicate with any person.

Being gone from the city, they lodged in a small town, where they set in order all the papers, ingrossing only what was necessary; and because the papers were many and there was much to write, they helped themselves with three men. And having ingrossed all that they were to carry to the Court, they burned all the rest. And because these three men whom they took for helpers should not spread abroad any thing of that which they had seen or written, they left them shut up with great vigilance, that none should speak with them; commanding to give them all things necessary very abundantly until the King's sentence came from the Court and was declared. The papers being presented at Court, and all seen by the King and by all his officers, sentence was pronounced in the form and manner following.

CHAPTER XXVI

Which contains the sentence that the King gave against the Louthias in favour of the Portugals.

Before we put down the sentence, it is convenient to note certain things. The first is that the sentence was much more extensive and lengthy than what is here summarized, and whereas the Portugals who had it in their possession curtailed it, I curtailed it still further, taking only the chief matter of it and cutting all the rest. {34}36 Secondly, it must be noted, for to understand some obscure points thereof, that poutoos•{35}37 are coastguards of the sea, and are certain condemned criminals wearing red caps, 38 who are sentenced to serve as men-at-arms in the frontier regions. Besides this, you must know that the duties of China are not paid as they are among us, but as they are paid in Sião, which is by measuring the ships which take the goods from China, from poop to prow in cubits, and the payment is adjusted according to the cubits, so much for each one; {36} and the present mode of payment in China at so much per cent, was by an agreement which was made by the Portugals, with the rulers of Cantam• through the advice of the Chinas who trafficked among the same Portugals, whereby the duties are heavier than they would have been if they were paid according to the custom of the country. {37}39 These things presupposed, the sentence is the following.

Pimpu•{38}40 by command of the King. Because Chaipuu Huchim41 Tutão•{39} without my commandment, or making me privy thereto, after the taking of so much people commanded them to be slain. I being willing to provide therein with justice, sent first to know the truth by Quinsituam• 42 my Quinchai, {40}who taking with him the Louthias whom I sent to inform me of the truthfulness of the Portugals and also of the Aitão{41} and Luthissi{42}who had informed me that the Portugals were pirates and that they came to all the coast of my realm to rob and to murder. And the truth of all being known, they are come from doing that which I commanded them. And the papers being seen by my Pimpu and by the great Louthias of my Court, and well examined by them, they came to give me account of all. And likewise I commanded them to be perused bu Ahimpu•{43} and Aty Chaḽ•{44}43 and by Athoglissi Chuquim,•{45}44 whom I commanded to oversee these papers very well because the matters were of great weight, wherein I would provide with justice. Which thus being seen and perused by them all, it was manifest that the Portugals had come for many years to the coast of Chincheo to drive their trade, which it was not convenient they should do in the manner they did it, but in my markets, as was always he custom in all my ports. These men of whom hitherto I knew not: I know now that the people of Chincheo went to their ships in the offing of trade, whereby I know already that they are merchants and not pirates, as it was reported to me that they were. I do not blame merchants for helping merchants, but I find great fault with my Louthias of Chincheo: because as soon as any ship came to my ports, they should have known if they were merchants, and if they wished to pay me duties, and if they would pay them, to write unto me at once. If they had done so, 45 so much evil had not been done. Or when they were taken, if they had let me know it, I would have commanded to set them at liberty. And althought it be a custom in my ports that the ships which come unto them be measured for to pay their duties, these being from very far off, it was not necessary but to let them do their business, and go for their countries. Besides this my poutoos{46} who knew these men to be merchants did not tell me, but concealed it from me, whereby they were the cause of many people being taken and slain. And those that remained alive, as they could not speak, did look toward heaven, and demanded from their hearts justice of heaven [they know no other supreme God but the heaven]. {47}46 Besides these things I know that the Aitão and the Luthissi did so much evil for covetousness of the many goods which they took from the Portugals, and paid no regard whether those whom they took, and took the goods from, were good or evil men. Likewise the Louthias along the sea-coast, knew these men to be merchants and certified me not. And all of them, as evil, were the cause of so much evil. I knew further by my Quinchay that the Aitão and the Luthissi had letters by the which they knew that the Portugals were merchants and not pirates; and knowing this they were not contented with the taking of them, but they wrote many lies unto me, and were not contented with kiling of the men, but killed children also, cutting off the feet of some, and the hands of others, and at last the heads of them all, writing unto me that they had taken and slain Kings of Malacca. Which reason I believing to be true, grieved in my heart. And because hitherto so many cruelties have been used without my commandment, from henceforward I command they be not done. Besides this the Portugals resisted my fleet, being better to have let themselves been taken than to kill my people. Moreover it is a long time since they came to the sea of my realm to trade like pirates and not like merchants, wherefore if they had been natives as they are strangers, they had incurred pain of death and loss of goods, wherefore they are not without fault. The Tutam by whose commandment those men were slain{48} said that for this deed I should make him greater; and the people that he commanded to be slain, after they had no heads, their hearts, that is their souls and their blood, required justice of heaven. I seeing so great evils to be done, my eyes could not endure the sight of the papers for tears, and my heart was very sad. I known not why my Louthias having taken these people did not let them go, so that I might not come to know such great cruelties. [Note the natural clemency of the heathen King, which is still further provoked by the merciful laws of his country, which as we said are very merciful regarding the deaths of malefactors and slow in executing them. Now to continue with the sentence]. {49} Wherefore seeing all those things, I do create Senfuu•{50} chief Louthia,• because he did his duty in his charge and told me the truth. I create also chief Louthia Quinchio•{51} because he wrote the truth to me of the poutoos{52} who went to traffic their merchandise in secret with the Portugals at sea.

Those who are evil I will make them baser than those who sow rice. Futhermore, because Pachou•{53}47 did traffic with the Portugals, and for bribes did permit the merchants of the region to go and traffic with the Portugals, and yet doing these things wrote unto me that the Portugals were pirates and that they came to my realm only to rob. And the same he said also to my Louthias, who immediately answered that he lied, for they knew already the contrary. And therefore so-and-so and so-and-so [here he nameth ten Louthias], {54} it is nothing that all of you be degraded to red-caps, {55} to which I hereby condemn you, but you deserve to be made baser as I do make you.

Chaẽ, for taking these men thou sayedst thou shouldest be greater, and being in the doing of so much evil thou syedst thou didst not fear me. So-and-so [here he named nine persons] you say that for the taking of these men I would make you great, and without any fear of me you all lied [he nameth many]. I know also you took bribes. But because you did so, I make you base [he depriveth them of the dignity of Louthias] so-and-so and so-and-so [naming many].

If the Aitão and the Luthissi would kill so many people, wherefore did you suffer it? But seeinmg that in consenting you were accessory with them in their death, you are all in the same fault. Chifu•48 and Chãchifuu,•{56}49 you were also agreeing to the will of the Aitão and Luthissi, and were with them in the slaughter, as well of those who were guilty as of those who were not. Wherefore I condemn you all to red-caps.

Lupuus{57} had a good heart, because the Tutão being willing to kill this people, he said that they should let me first know it. To him I will do no harm, but good as he deserveth, and I command that he remain Louthia.

Sanchi•{58} make my Anchessi of the city of Cansi.•{59}50 The Antexeo•{60} I command to be deposed of his honour. Assão•{61} seeing he can speak with the Portugals, let him have honour and ordinary, and he shall be carried to Chaqueã • [Chekiang]• where he was born. [This is the youth with whom the Portugals did defend themselves serving them for interpreter; they gave him title of Louthia and maintenance].

Chinque,· {62} head of the merchants that went to sea to traffic with the Portugals and deceived them, bringing great store of goods on shore, it shall be demanded of him and set in good safeguard for the maintenance and expenses of the Portugals, and I condemn him and his four companions to red-caps, and they shall be banished whither my Louthias shall think good.

To the rest, guilty or imprisoned for this matter, I command my Louthias to give every one the punishment he deserveth.

I command the Chaẽ to bring me hither the Tutão, that his faults being perused by the great men of my Court, I may command to do justice on him as I think good. This Tutão was also a consenter in the wickedness of the Aitão and the Luthissi; for the Luthissi and the Aitão made him partaker, and gave him part of the booty which they took from the Portugals, that as the head he should hold for good that which they did: for in truth they durst not have done that which they did if he had not given consent and agreed with their opinion. [This man hearing what was judged against him, hung himself, saying that seeing Heaven had made him whole, that no man should take away his head]. {63} The Poutoos who are yet in prison, shall be examnined again, and shall be dispatched forthwith.

Chichũ, {64} shall forthwith be deprived from being a Louthia, without beinhg heard any more.

Chibee, •{65} head of six and twenty, I command that he and his be all set at liberty, for I find but little fault with them. Those who owe any money, it shall be recovered of them forthwith.

Famichim• and Toumichar•{66} shall die, if my Louthias do think it expedient, and if not let them do as they think best.

Afonso de Paiva e Pero de Cea [these were Portugals] Antonio and Francisco [these were slaves]{67} finding them to be guilty of killing some men of my fleet, shall with the Luthissi and he Aitão be put in prison, where according to the custom of my kingdom, they all shall die slowly.

The other Portugals who are alive with all their servants, who are in all fifty-one, I command them to be carried to my city of Cansi, {68} where I command them to be intreated, seeing my heart is so good towards them that for their sake I punish in this sort the people of my country. And I deal so well with them, because it is my custom to do justice to all men. The Louthias of the fleet, finding they are little to blame, I command they be set free. I deal in this sort with all men, that my Louthias may see that all that which I do, I do it with a good zeal. All these things I command to be done with speed. Thus far the sentence of the King. 51

The process of this sentence hath clearly shown the good process and order of justice which these idolatrous and barbarous peoples have in their way, and the natural clemency which God hath put in a King who liveth without knowledge of the true God. And how great diligence he putteth, and with what consideration he treateth weigthy matters, 52 seemeth to be the cause of the good government which thee is in this country and the great justice thereof; for as much as although China is such a great kingdom as we have shown, it has been maintained in peace since a very great number of years without any rebellions; and God sustains it, because the enemies do not make raids and devestation therein, and because commonly it is sustained in great abundance, prosperity and plenty. 53 And the rigorous justice of this land is the cause of bridling the evil inclinations and inquietudes to which the people thereof are prone, which being so strict as it is, yet withal the prisons are commonly full of prisoners, there being so many of them, as we have said. And if some year there should chance to be a famine, it is necessary, both within the land as along the seacoast, to maintain continuously many fleets to repress the depredations of the many pirates who rise up in arms.

The Portugals who were freed by the sentence, when they carried them whither the King commanded, found by the wall all things necessary in great abundance, in the houses which (as we said above) the King had in every town for the Louthias when they travel. They carried them on parties, in chairs made of canes upon men's backs, and they were in charge of inferior Louthias, who caused them to have all things necessary though all the places where they came, till they were delivered to the Louthias of the city of Cansi.

From thenceforward they had no more of the King every month but one foo{69} of rice54 (which is a measure as much as a man can bear on his back), the rest they had need, every one did seek it by his own industry. Afterwards they dispersed them again by two and two and by three and three through divers places, to prevent that in time they should not become mighty by joining themselves with others.

Those that were condemned to death, were forthwith put in the prison of the condemned. And Afonso de Paiva found a mean to give the Portugals who were free to understand that for his welcome they had given him forty stripes straightaway, which had caused him to suffer very much, showing himself comforted by the Lord.

Those who were at liberty, now some and then some, came to the ships of the Portugals through the industry of some Chinas, who brought them very secretly, moved by the great bribes which they received from the Portugal merchants who drove their trade in the city of Cantão.

Revised reprint of:

[CRUZ, Fr. Gaspar da], Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...], in BOXER, Charles Ralph, ed., [Camões Professor of Portuguese, University of London, King's College], in "South China in / the Sixteenth Century/ [Being the narratives of/ Galeote Pereira / Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O. P. / Fr. Martín de Rada, O. E. S. A. / (1550-1575)]", London, Hakluyt Society, 1921, pp.45-240 [second series, No. CVI] (issued for 1953), pp. 190-211.

For the Portuguese text see:

CRUZ, Fr. Gaspar da, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Discurso de Navegação, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.77-87 - For the Portuguese modernised version by the author of the original text, with words or expressions between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese text, see:

DE LA CRUZ, Gaspar, PERES, Damião, ed., Tratado das coisas da China a de Ormuz, Barcelos, Portucalense Editora, 1937, pp. 123-146 - Partial transcription.

For the original source of the English translation see:

BOXER, Charles Ralph, ed., [Camões Professor of Portuguese, University of London, King's College], in "South China in / the Sixteenth Century/[Being the narratives of/ Galeote Pereira / Fr. Gaspar da Cruz, O. P. / Fr. Martín de Rada, O. E. S. A. / (1550-1575)]", London, Hakluyt Society, 1921, [second series, No. CVI] (issued for 1953), p. vii-[...], the translation of the Tractado of Gaspar da Cruz is based on Samuel Purchas' pioneer English translation, 'A Treatise of China and the adjoining regions, written by Gaspar da Cruz a Dominican Friar, and dedicated to Sebastian, King of Portugal: here abbreviated', printed in Purchas his Pilgrimes (London, 1625), III, pp. 166-198. I have restores Purchas' omissions (amounting to about one-third of the original text) and corrected and amplified his translation where a careful comparison with the original Portuguese edition of 1569-70 showed this justified.

NOTES

The numeration of these notes specifically refer to the section of Gaspar da Cruz's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.85-87.

The prevailing numeration of these notes is indicated between curly brackets « { }» and is cross-referenced to Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation [CRB] of Gaspar da Cruz's original text, indicated immediately after, in between flat brackets « [ ]».

The contents of these notes have been transferred in their entirety exactly as they appear in Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation of Gaspar da Cruz's text, and do not follow the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

Whenever followed by a superciliary asterix« * », these notes' bibliographic references are alphabetically repertoried according to their author's name in this issue's SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY following the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

{1}[CRB, p.190, n. l] Cf. introduction,* pp. xxiii-xxxv, and the sources there quoted.

{2}[CRB, p.190, n.2] Should be Simão de Andrade. See p.187, n. (4) above.

{3}[CRB, p. 191, n.1] Fan-kuei, • (Cantonese, faan-kwai), • 'Barbarian devil'. Also romanised as Fanqui, • Fankwei, • etc. Cf. Giles, Glossary,* pp.6-7, 40-41.

{4}[CRB, p.191, n.2] Fan-jên• (Cantonese, faan-yân)• 'Barbarian'. Cf. Giles, op. et loc. cit.

{5}[CRB, p.191, n.3] First promulgated in 1404, on the grounds that the people of Chekiang• and Fukien• often became pirates. This particular order was soon modified, but similar prohibitory decrees were promulgated after the death of the Yung-lo• emperor in 1424. Cf. T'oung Pao,* XXXIV, pp.364-365, 388-389.

{6}[CRB, p.192, n. l] Another mistake for Simão de Andrade.

{7}[CRB, p.192, n.2] Ningpo. •

{8}[CRB, p. 192, n.3] Cf. introduction, pp. xxiii-xxiv, and sources there quoted.

{9} [CRB, p. 192, n.4] This is likewise confirmed by Chinese chronicles of the Ming period. Cf. W. H. Chang, Commentary,* pp.38, 42-43; T. T. Chang, Sino-Portuguese Trade,* pp.69-72; J. M. Braga, Western Pioneers,* pp.68-69, 72.

{10}[CRB, p.192, n.5]The vicinity of the Bay of Amoy, • in this context. Cf. Appendix I.

{11}[CRB, p.192, p.6] 'Cantão',• means in this context, the province (rather than the provincial capital) of Kuangtung. •

{12}[CRB, p.192, n.7] Nanking. • 'Beyond' is rather misleading since the Yangtze• delta region and the islands off the coast of Chekiang• are presumably meant here.

{13}[CRB, p.192, n.8] Shuang-hsü-chiang, •'Double island anchorage' nor far from Ningpo. • Cf. Ch'ou-hai-t'u-pien,* chüan 8, p.22; T. T. Chang, Sino-Portuguese Trade, pp.76-77; W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.38-39.

{14}[CRB, p.193, n.1]A stone pillar or column which sereved as the emblem of a municipality, and also as a whippingpost where public punishment was inflicted on a delinquent, somewhat after the manner of stocks in English towns. Some typical colonial pelourinhos are described by Luis Chaves, 'Os Pelourinhos de Portugal nos domínios do seu império de Além-Mar',* in Ethnos, I, pp.91-112.

{15}[CRB, p.193, n.2]Fukien. •

{16}[CRB, p. 193, n.3] It is evident from contemporary Ming records that these events took place in the region of the Bay of Amoy, chiefly Yüeh-chiang ('moon anchorage') near the modern Hai-ts'ang • on the south side of Amoy Bay, and off the island of Wu-hsü, • as shown in Fig. (ii). The Chinese admiral who took the bribe was probably Yao Hsiang-fêng, • the acting Hai-tao-fu-shih,· who seems to have been cashiered in consequence. Cf. W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.39-40.

{17}[CRB, p. 194, n. 1 ] From the Ming records quoted by W. H. Chang (Commentary, p.41), it is clear thast the events narrated in this chapter took place in the coastal district of Chao-an,· on the Funkien•-Kuantung border.

{18}[CRB, p.194, n.2] 'Selling' or 'disposing of'.

{19}[CRB, p.195, n.1] This engagement took place at Tsouma-ch'i• ('running horse creek') on the T'ung-shan• peninsula. Cf. introduction, pp. xxvii-xxviii.

{20}[CRB, p. 195, n.2 ] Lu T'ang, • the Pei-wo-tu-chih-huiu, • this being the title of a military commander whose chief function was to guard the coast against the attacks of Japanese. He was a native of Ju-ning • in Honan • province. Chinese records differ as to whether Lu T'ang at this date was holding this post, or if (as is probable) he had been promoted to Tu-ssu, • or provincial army commander, as a result of his destruction of the pirate stronghold at Shuang-hsü-chiang• a few months before. In any event, as pointed out previously, Gaspar da Cruz has confused Lu Tang's name with his appointment and thus produced his hybrid Luthissi.· Cf. Ch 'ou-hai-t'upien, Ch.4, p.12, Ch.8, p.23; Ming-shih,* Ch.212, biography nr.6.

{21}[CRB, p.196, n.1] The Hai-tao-fu-shih, • or admiral of the coastguard fleet, who at this date was K'o Ch'iao, according to the Ming records. There is apparently some confusion in our friar's account between this Hai-tao, • and the Viceroy (Tu-t'ang), • Chu Wan. • For K'o Ch'iao· biography see W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.40-41. He was a native of Ch'ing-yang. • in Kiangnan• province.

{22}[CRB, p.196, n.2] The original Portuguese text has capoeiras ('chicken coops') but I have retained Purchas'* translation of pillory-coops as being a better description. Cf. Galeote Pereira, pp.24-25 above {or Text 8 - Galeote Pereira}

{23}[CRB, p. 197, n. 1 ] The contemporaneous Ming shih-lu* ('Veritable records'), as quoted by W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.41-42, gives ninety six men as the total number executed, 'including the bogus lieutenant, Li Kuang-tou.'• The majority were Chinese.

{24}[CRB, p. 197, n.2] All the old Portuguese accounts have similar statements about the infliction of the death penalty in Ming China. The rule that all death sentences in normal pece time required confirmation from the Throne, and that execution could only be carried out at the annual autumn assizes, apparently dates from the reign of the first Emperor of the Sung• dynasty. Cf. Giles, Biographical Dictionary,* nr.68, p.70; Couling, Encyclopedia Sinica,* p.467; China Review, XIII, 401.

{25}[CRB, p. 199, n. 1 ] Ch'in-ch'ai,• Imperial Commissioner or Legate. Cf. Ch. XVI, p. 157, n. ( 1) above.

{26}[CRB, p. 199, n.2] The supervising Censor, Tu Ju-chên, • president of the Board of War (ping-pu)• at Peking, • and the Censor, Ch'en Tsung-k'uei, • are the only high officials explicitly mentioned in the Ming Shih-lu as forming part of the commission of enquiry, but doubtless some others accompanied them. Ming shih-lu, Ch.347, 363.

{27}[CRB, p.200, n. 1 ]Probably Ch'en Tsung-k'uei is meant here.

{28}On the Chinese judge acting as prosecutor, cf. Dyer Ball, Things Chinese,* p.333.

{29}[CRB, p.201, n. l] The region of the Bay of Amoy in this context. Cf. Appendix I.

{30}[CRB, p.201, n.2] i. e., Lu T'ang• and K'o Ch'iao. Cf. W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.42-43.

{31}[CRB, p.201, n.3] Ningpo.•

{32}[CRB, p.202, n. l] Lu T'ang, then apparently the Tu-ssǔ,• or commander of the provincial troops.

{33} [CRB, p.203, n. l]Lu T'ang and K'o Ch'iao.

{34} [CRB, p.204, n. 1 ] I have not been able to trace the full text of the original decree, but Gaspar da Cruz's summary records accords remarkably well with the much briefer extracts and references which are embodied in the Ming shih-lu and elsewhere, and reproduced in W. H. Chang, Commentary, pp.42-43.

{35}[CRB, p.204, n.2] Pu-tu,• 'turban-heads', would seem to be the Chinese term indicated here, though I have not found it applied elsewhere to military convicts. For the employment of banished criminals as military convicts, see the extracts from the Shu-yüan Tsa-chi• and the Ming-shih, translated in T'oung Pao, XXXIV, pp.393-394.

{36}[CRB, p.204, n.3] After 1578, however, the Portuguese had to pay customs duties as well as the anchorage dues involved. Cf. Ljungstedt, Historical Sketch,* pp.87-90, 210-211.

{37}[CRB, p.204, n.4] For the agreement made by Leonel de Sousa with the Kuangtung· provincial mandarins in 1554. Cf. J. M. Braga, Western Pioneers,* pp.83-89, 202-210.

{38}[CRB, p.205, n.1] Ping-pu,• The Board of War at Peking.

{39}[CRB, p.205, n.2] Probably a corrupt and abbreviated version of some of Chu Wan's• official titles.

{40}[CRB, p.205, n.3] Probably refers either to Tu Ju-chên,• or to Ch'en Tsung-k'uei.•

{41}[CRB, p.205, n.4] The Hai-tao-fu-shih, · or naval coastguard fleet commander, K'o Ch'iao.

{42}[CRB, p.205, n.5] Lu T'ang, who was then either Tussǔ or Pei-wo-tu-chih-hui.• Cf. Ch. XXIV, p. 195 above.

{43}[CRB, p.205, n.6] The Hsing-pu, · Board of Justice, or Board of Punishments at Peking.

{44}[CRB, p.205, n.7] Probably a reference to the Tu Ch'a Yuan, · the Censorate, or Court of Censors.

{45}[CRB, p.205, n.8] This defeats me, but may conceal some reference to the fact that the preliminary investigation at Peking was carried out by the Board of War in consultation with three judges. See: Ming shihlu, Ch.347, as quoted in W. H. Chang, Commentary, p.42.

{46}[CRB, p.206, n. l] Compare p.204, n. (2) above.

{47}[CRB, p.206, n.2] The interpolation in brackets is by Fr. Gaspar da Cruz.

{48}[CRB, p.206, n.3] The Tu-t'ang Chu Wan.

{49}[CRB, p.207, n. l] The interpolation in brackets is likewise by Fr. Gaspar da Cruz.

{50}[CRB, p.207, n.2] Not identified.

{51}[CRB, p.207, n.3] Not identified.

{52}[CRB, p.207, n.4] See: p.204, n. (2) above.

{53}[CRB, p.207, n.5] Possibly a reference to one of the local pa-tsung, · for whose functions at this period cf. Rada's narrative, p.243, n. (1) below.

{54}[CRB, p.207, n.6] Another interpolation by Fr. Gasparda Cruz, as are those which follow in square brackets.

{55}[CRB, p.207, n.7] Military convicts.

{56}[CRB, p.208, n.1] Chifu is probably Chih-fu, · prefect, in this instance Lu Pi, · the prefect of Chang-chou• who was degraded for complicity in this affair. Cf. China Review, XIX, 50; Chang-chou-fu-chih, Ch.47, p.21.

{57}[CRB, p.208, n.2] Seems to be confused with the prefectLu Pi, · who was, however, one of the guilty.

{58}[CRB, p.208, n.3] Not identified.

{59}[CRB, p.208, n.4] Provincial Judge or Judicial Commissioner at Kueilin. ·

{60}[CRB, p.208, n.5] Not readily identifiable among the list of those disgraced given in the Ming shih-lu.

{61}[CRB, p.208, n.6] Presumably A (Ah) something or other.

{62}[CRB, p.208, n.7] Not identified.

{63}[CRB, p.209, n. l] This interpolation on the suicide of Chu Wan is by Fr. Gaspar da Cruz.

{64}[CRB, p.209, n.2] Not identified.

{65}[CRB, p.209, n.3] Not identified.

{66}[CRB, p.209, n.4] Not identified.

{67}[CRB, p.209, n.5] Words in brackets are interpolated by Fr. Gaspar da Cruz. For the Chinese translation of the Portuguese names, cf. Ming-shih-lu, Ch.363 in W. H. Chang, Commentary, p.42. As noted in the introduction, after the suicide of Chu Wan. Lu T'ang, K'o Ch'iao and others had their death sentences communted, and were shortly afterwards pardoned. Cf. W. H. Chang, Commentary, p.43, and China Review, XIX, 50.

{68}[CRB, p.209, n.6] Kueilin. T. T. Chang (Sino-Portuguese Trade, p.84) and other commentators wrongly identify this city as Hangchow, ·evidently confusing the Portuguese 'Cansi'· with Marco Polo's 'Quinsay'.· But from the texts of Cruz and Pereira it is clear that by 'Cansi' the Portuguese meant Kuangsi. ·

{69}[CRB, p.210, n.1] fen• or fun, · the 1/100 part of a Chinese ounce of silver.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Gaspar da Cruz's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.85-87.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics « " "» - unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated - followed by the spelling of Charles Ralph Boxer's English translation [CRB], indicated immediately after, between quotation marks within parentheses « (" ") ».

1 The author makes reference to a group of Portuguese captured in 1549 by Chinese troops on the coast of Fujian. · Galiote Pereira was among these prisioners. Throughout his Tratado [...] (Treatise [...]), the author frequently makes allusions to Algumas coisas sabidas da China [...] (Certain Reports on China [...]) of China elaborated by Galiote Pereira after his release. (See: Text 8-Galiote Pereira).

2 The Portuguese regularly visited the China shores between 1530 and 1554, trading with local merchants on deserted places along the coast. Portuguese sixteenth century charts of this period attest the founding of some ephemeral factories, the most famous of which was"Liampoo",• [Port.: "Liampó"], in the vicinity of Ningbo· [Port.: "Nimpó"].

3 Leonel de Sousa (°ca1500-†ca1572), native of the southern Portuguese province of Algarve and a captain with a long career in the Orient, established an informal agreement in 1554 with the mandarins [Chinese government officials] from Guangdong, which allowed the Portuguese merchants free trade in the estuary of the Zhujian• (Pearl River), first in Lanbaijiao•[Port.: "Lampacau"] and then Aomen ·[Port. "Macau"]

4 First clashes between Portuguese and Chinese are traditionally attributed to Simão de Andrade, the brother of Fernão Peres de Andrade, during a visit to Tunmen• [Port.: "Tamão"] island, in 1519, the Chinese authorities from Guangdong" ·only officialy severing their relations with the Portuguese in 1522.

5 "fancui"[original Port.1]("Fancui") = fangui [zi]· [Chin.]: literaly meaning, 'foreign devils'.

6 "fangim"[original Port.]("Fangim") = yangren • [Chin.]: literaly meaning, 'overseas people'.

7 "loutia[s]"[original Port.]("Louthia[s]") = · laodie• [Chin.]: literaly meaning, 'venerable father'- an honourable attribution to Chinese civil servants. Galiote Pereira uses the same term,"loutea". •(See: Text 8-Galiote Pereira)

8 The author makes reference to internal transport system of the Ming· dynasty.

9 The"[...] partes do Sul [...]"("[...] parts of the South [...]") of the sixteenth century authors comprehended a vast geographic region east of Malacca [presently Melaka], which at present is generically called Far East.

10 "[...] Fernão de Andrade [...]" ("Fernaõ Peres de Andrade") should be 'Simão de Andrade'.

11 "Liampó"· [Port.] ("Liampoo") = Zhejiang· [Chin.]: meaning in this context, the coast of this province. ·

12 "terçavam "("[...] were the intermediaries [...]"): meaning, 'serviam de terceiros' ('acted as intermediaries').

13 "Chincheu"· [Port.] ("Chincheo") = meaning in this context, the region of Xiamen· Bay [Bay of Amoy] near the city of Zhangzhou. •

14 "[...] ilhas de Cantão, [...]" [Port.] ("[...] islands of Cantão."): meaning in this context, the islands in the vicinity of the city of Guangzhou. ·

15 It is unlikely that in those times the Portuguese went as far as Nanjing. ·

16 It is unlikely that the Imperial Court was not aware of the troubled events occuring in the southernmost regions of the Middle Kingdom at the time. Because the Chinese government's system kept the provinces under close survey continuously at the time, detailed reports on the rampant piracy which assailed the coastal provinces of the Empire must have certainly reached the Imperial Court, in Beijing.

17 "Liampó"[Port.] ("Liampoo") = Shuangyu·[Chin.]: meaning in this context, the islands of this group whichbelong to the Zhoushan ·archipelago near the Chinese city of Ningbo-where Portuguese and foreign traders jointly founded a temporary factory, until their expulsion in 1549.

18 In Portugal, the 'forca' ('gallows') and the 'pelourinho' ('whipping-post') were the traditional symbols of municipal authority.

19 The circunstances under which the Portuguese might have committed some sort of plundering in the coastal area around the city of Ningbo and the Shuangyu Islands are yet to come to light, although is it hypothesised that these depredations were connected to acts of piracy committed by Chinese intermediaries.

20 In 1548, the Chinese Imperial Court dispatched the Viceroy Zhu Wan· to the meridional provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian, charging him with the mission to eridicate the outburst of piracy which devastated those regions.

21 Contrary to what the author states, Zhu Wan commanded a Chinese armada to attack the Portuguese factory of Ningbo [Port.: "Liampó"] halting the thriving illegal trade developed by the foreigners. After the assault to Ningbo the Imperial comissioner Zhu Wan promoted a violent campaign in the Zhangzhou [Port.: "Chincheu"] coast - where the Portuguese had meanwhile seeked protection - against foreign vessels.

22 Diogo Pereira, was a well-known Portuguese merchant owner of the two junks berthed in the Chinese coast, on board of which was Galiote Pereira, one of the main informers of the author. (See: Text 11 - Gaspar da Cruz)

23 "[...]fazendo querena [...]"(lit.: '[...] make keel [...]' or "[...] dressing [...]"): in this context possibly meaning a'provocação'('provocation'). In Portuguese 'querena' ('keel') is the part of the vessel under water but 'dar querena' (lit.: 'give keel') means 'destruir' ('to destroy'), a similar expression to the one used by the author.

24 "lutici"· [original Port.] ("Luthissi") = ludusi'[Chin.]: • the commander of a Chinese province's armed forces.

25 "aitão"[original Port.] ("Aitão") = haidao•[Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's coastal defense forces with powers of jurisdiction upon foreigners.

26 As the author himself previously made reference, in times of peace all death sentences had to be sactioned by the Emperor, the sentence being applied on yearly prescribed dates. Acting otherwise, the Fujian mandarins had seriously contravened their powers.

27 The ludusi responsible for the capture of Diogo Pereira's junks was called Lu Tang• ("Lu Tang").

28 The haidao in charge of the coastal area of the Fujian province was called Kejia· ("K'o Ch'iao").

29 "quinchai"• [original Port.] ("Quinchay")= quinchai[Chin.]: an Imperial commissioner or Imperial delegate, appointed with full powers in emmergency situations.

30 "anchaci"• [original Port.] ("Anchassi") = anchashi•[Chin.]: judge of a Chinese province. "pochanci"• [original Port.] ("Pochanssi") = buzhengshi• [Chin.]: the treasurer of a Chinese province.

31 The two Imperial censors called Du Ruzhen •("Tu Juchên") and Chen Zongkui• ("Ch'en Tsung-k'uei") were certainly accompanied by other civil servants of a lesser rank.

32 "chaém"• [Port.] ("Chaḽ") = chayuan• [Chin.]: an itinerant Imperial censor invested with the functions of Imperial commissioner during his obligatory yearly inspection rounds to a number of the country's provinces.

33 "[...] se se encontravam."("[....] if they did agree."): meaning, 'se contradiziam' ('contradict themselves').

34 "Chincheu" [Port.] ("Chincheo") = Fujian• [Chin.]: meaning in this context, the coastal area of this Chinese province.

35 According to the author's statements the Portuguese were to blame for serious depredations to the coastal area around the city of Ningbo and the Shuangyu Islands.

36 The author seems to have obtained from one of the former Portuguese prisioners a copy of the sentence issued by the Imperial authorities.

37 "poutó[s]"• [original Port.] ("poutoo[s]") = butou• [Chin.]: most probably, literaly meaning, 'turban-heads' - although this term is not listed in the Luso-Asian glossaries.

38 "[...] "capacete[s] vermelho[s]" [...]" ("[...] red cap[s], [...]") or 'barrete[s] vermelho[s]' ('red barret[s]'): an appellation given to criminals who, for one reason or another, were forced to military service in the [remotely harsh] border regions of the Chinese Empire.

39 Although custom duties in Chinese ports were traditionally charged according to the vessels' volume of cargo, it seems that after their informal agreement with Leonel de Sousa the mandarins [Chinese government officials] from Guangdong charged duties based on the value of the merchandise rather than on the bulk volume of the vessels.

40 "Pimpu"• [original Port.] ("Pimpu") =Bingbu• [Chin.]: the Board of War in Beijing, one of the major Ministries of the Chinese Imperial government.

41 "[...] Chaipu Huchim [...]"[Port.] ("[...]Chaipuu Huchim [...]"): most probably, the haidao Zhu Wan, the major responsable for the capture of the two Portuguese junks.

42 Although the author's transcription from Gaspar da Cruz is not according to official Chinese documentation, it has been clearly established that the Imperial commission in charge of the enquiry was headed by Du Ruzhen, a high ranking civil servant from the Board of Justice, in Beijing.

43 "Ahimpu"[original Port.] ("Ahimpu") = Xingbu• [Chin.]: the Board of Justice, in Beijing. "Atuchaém"• [original Port.] ("Aty Chaḽ") = Duchayuan• [Chin.]: the Censorate, in Beijing. They were two of the major Ministries of the Chinese Imperial government.

44 "[...]Athailissi Chunquim [...]"[original Port.] ("[...] Athoglissi Chuquim [...]"): unidentified expression, but possibly meaning, a Chinese governmental body.

45 "Se assim ofizeram, [...]"("If they had done so [...]"): meaning, 'se assim o tivessem feito'('if they had done so').

46 A reference to the Chinese belief that Tian· (Heaven God) is the beginning and end of all things.

47 "pachou" [original Port.] ("Pachou") = bazong• [Chin.]: the commander of a guarrison of about three thousand men.

48 "chifu"[original Port.] ("Chifu") = zhifu• [Chin.]: the Mayor of a town.

49 "chanchifu"• [original Port.] ("Chãchifu") or "cancheufu"• = zhangzhoufu• [Chin.]: literaly meaning, 'audience room of a town hall' - but which in this context could make reference to a 'civil servant' of a 'prefecture'.

50 "Cansi" [Port.] ("Cansi") = Guilin• [Chin.].

51 The Memorial compiled by the author comes to an end here. As previously stated, the major responsible for the capture of the two Portuguese junks, Zhu Wan, commited suicide before hearing the outcome of the Imperial justice. Many of his collaborators, originally sentenced to a variety of punishments, would later be pardonned by the Emperor. The Portuguese survivors were exiled to the city of Guilin, in the province of Guangxi. ·Thanks to the cumplicity of Chinese merchants duly bribed by Portuguese who started to trade along the coast of the province of Guangdong from 1549 onwards, a few of these Portuguese exiles managed to escape during the following years.

52 The Portuguese witnesses who followed the proceedings against their compatriots were extremely well impressed by the zeal of the Chinese justice in the way it favoured the foreigners and punished the high ranking provincial civil servants. Later it became clear that the outcome of the litigation proceedings on the two junks did not rest solely on the imparciality of Chinese justice but was also affected by important local lobbies adversely affected by the anti-foreign policy promoted by Zhu Wan.

53 China was also at the time seriously afflicted by the relentless onslaught of internal strife and external incursions although, due to the comparative enormous extent of the Chinese empire in relation to contemporary dimmensions of European states, the general situation seemed to be one of unshakeable stability.

54 "fom"• [original Port.]("foo") = fen• [Chin.]: an old Chinese currency coin equivalent to one hundredth of a tael or a Chinese ounce of silver. The subjective unit of measurement mentioned by the author does not comply with other sources by Portuguese contemporary chroniclers which value it as aforesaid.

start p. 97

end p.