It is said to be a vast territory abundant in all kinds of provisions that can be imagined and all varieties of fruits that can be found in Spain. 1 It has many gold and silver mines as well as of all other minerals. It is a land of much and very fine silk with which are woven damasks, satins, velvets, taffetas, brocades and brocatels. It is also rich in rhubarb, camphor, excellent cinammon, quicksilver, alunite and porcelain. Many Chinese merchants deal with all these products exporting them from mainland China in large junks; their trade making them very rich. There is also much musk and ambergris. 2 In this land there are very many large cities enclosed within fortified walls and surrounded by moats. 3 {These cities} * have mighty buildings, both temples and residences exclusively occupied by heathens but all with such noble attitudes that Christians seem to have once lived in these regions. 4

They worship only one God and they believe Him to be the creator of the [whole] universe. They also worship three major masculine idols, their representations being exactly alike, and all three being of a single entity. 5 They also worship two feminine idols and believe they are saints. One of them is called Nama•6 and she is the mariners' safeguardian to whom they are greatly devoted and celebrate festively. 7 The other is called Conhãpuça·8 who, according to legend, is the daughter of a king of China. She left her father's abode never to return in order to pursue a solitary life until the end of her days. She is the guardian of the soil and is represented with a red beak dove. 9 { The Chinese} also worship a number of other idols whose images are kept in sumptuous temples which they call varelas and which, according to the historians, resemble the pyramids of Egypt. 10 [These varelas]are richly adorned with the aforesaid images being on altars greatly resembling ours.

These varelas are the homes of Friars whose lives {are dedicated to} serve God and who publicly celebrate the divine rites according to the rules of their cult. And when they officiate they wear paraments in the same way as the {Catholic} priests do when they say mass. The three officiates pray on an altar {reading the scriptures} in a book written in a language which is for the same as Latin is for us. Not all {Chinese} understand this language; the Friars being in possession of many book written thus. 11

In the same manner our monasteries do, these varelas enclose cloisters12 and a number of dormitories and workshops; displaying sundial clocks and well cast 'metal' bells adorned with gold lettering which are played by being struck with hammers. The Friars wear long yellow tunics and wear their heads shaved, their income being no more than what is strickly necessary to their nourishment, some eating neither meat nor fish. And in the same way as there are varelas for Friars so there are for nuns. 13

The Chinese have their own language which, in its tone and fluidity sounds like German. 14 Both men and women are fair skined and of pleasant countenance. Among them there are scholars in varied sciences which can be learned in the public schools and about which there are many excellent printed books. The Chinese are men of remarkable ingenuity, both in the liberal arts and in the mechanical crafts. There are masters in all professions manufacturing many fine works, such as porcelains, chests, baskets and many other beautifull objects traditional to this land {of China}. They are extremely courteous15 among themselves being proud of China's high sense of civility, considering all other peoples less civilized than the Chinese. They all very particular about maintaining high standarts of life, both in their attire and in their table manners, eating for the sake of hygiene17 {seated at} high tables covered with a cloth and {making use of} napkins and knives, each delicacy being presented on a different plate, 16 taking the food to their mouths with a fork. The men are feeble at war; but are provided with some good military equipment such as articulated corselets, 18 short sabers of tempered iron, 19 halberds, grapnels, javelins and bows and arrows, and even a few iron bombards. The fidalgos are called mandarins and ride on horses and when they go through town the streets empty of the common people.

{The Chinese} are a people extremely submissive of their superiors strickly complying with the commandments of their king. There is only one [king] in the whole of the Empire of China, who is one of the mightiest sovereigns in the whole world, both in the riches [he owns] as in the number of people [he rules upon]. He is a heathen. He is called "The Son of God and the Lord of the World".20 He possesses a charter in which is declared that he was conferred "[...] Peace by the Almighty [...] always found by those who sought to preserve it." He is personally attended by eunuchs. 21 He has many wives and young concubines, within a great walled precint which form the grounds of the royal palace, where every one of them live in private quarters attended by women servants and eunuchs. 22 Until not long ago the kings of China were elected but more recently the first male born by one of the king's wives -- but not of a concubine -- becomes the succeding ruling sovereign. 23 The other {royal sons} are not entitled to inherit, being relegated to specific cities {within the Empire} where they spend the rest of their lives confined to vast fortresses protected by heavy escorts. Here they live with their wives and enjoy life in many ways. They are not allowed to leave {the place where they live} without permission of the king and wherever they may go they are transported in {closed} palanquins, 24 which prevent them to see the route.

The king of China has made known throughout his kingdom that all men who might leave the mainland are never to return, under penalty of death. As it is common belief that there is no other place on Earth better than China, nor more plentiful in all basic human commodities, it is also taken for granted that all those who venture to another land are traitors to their own. 25 The Chinese who trade in export merchandise inhabit the ilha da Veniaga · (Island of Trade),· 26 who is eighteen leagues distant from the city of Guangzhou, the major coastal [metropolis] of China and a very important sea port. The king of China does not directly dispatch a single law, all government matters being delegated to officers which are in charge of dispatching his command. The administration of Justice, which is the foremost concern of the kingdom, is in the hands of three eminent scholars which are called Colaos:· 27 the 'high' Colao, the 'low' Colao, and another subordinate {to the former two}. {These Colaos} are elderly and reputed by their kindness, having being confered these posts through their good deeds and wisdom, after rising through many other official ranks before reaching that of Tutan.· 28 [Tutans] are governadores de comarca (county judges), and above them are the Anchassis29 which are secretários (secretaries) and above these are the Colaos, which are supreme magistrates. The rank of Colao can be occupied by someone once from a low social background, the exclusive conditions being that he must be an elder, a scholar and an honest and wise person. 30

Other [government posts are held by the Tutans, Conggnans, ·31 and Chumpims, ·32 which {triunvirate} constitute a conselho (Council), which is the ruling body of {Chinese}cities. The most important {of the three} is the Tutan, who must be an elder, a scholar and an honest and wise person. Next comes the Chumpim, who is not a scholar but more an armed forces' commander. The Conggnan is the third and, being in charge of the Treasure, is the lowest in this Council's hierarchy. Related to these there is another officer called Yussi,· 33 who must also be a scholar and an honest and wise person. Together with the Tutan he dispatches all matters pertaining to Justice being equally in charge of ruling over all inquests and public inquiries, reporting them to the king. He is very powerful but his one year appointment cannot be renewed. The [appointments] of the other {three} last for [three] years.

There are other lower rank government officers which are called Pochanssis, ·34 Amechassis, ·35 Tussis, 36 Aitans, ·37 and Pios, ·38 —which are almirantes (commanders) -- and Ticos, ·39 -- whose functions I could not find out; existing three categories in each rank:' high', 'low' and an even lower {subordinate position}. All these officials move about in sedan chairs accompanied by footmen carrying parasols, {and a retinue} more or less opulent according to their rank, it being publicly known not only by its specific display {of oppulence} but also by some boards {held by servants preceding the cortége} were are written all the honours of their ranks together with a number staffs -- which can be either of silver or tin, according to the dignatary's rank.

The most honourable {dignataries} are {entitled to} a three layered parasol of yellow silk, the lowest one being {entitled to a} black taffeta {parasol} of two or three layers. According to their rank so is the size of their armed escort and the welcome receptions at the gates of the cities where they hold their posts. The same applying for the speed with which the commoners desert the streets where they are due to pass and the number of men which preceed them loudly ordering their evacuation. And when a Yussi pass, {the streets} are entirely deserted, there being not a single soul in sight. 40

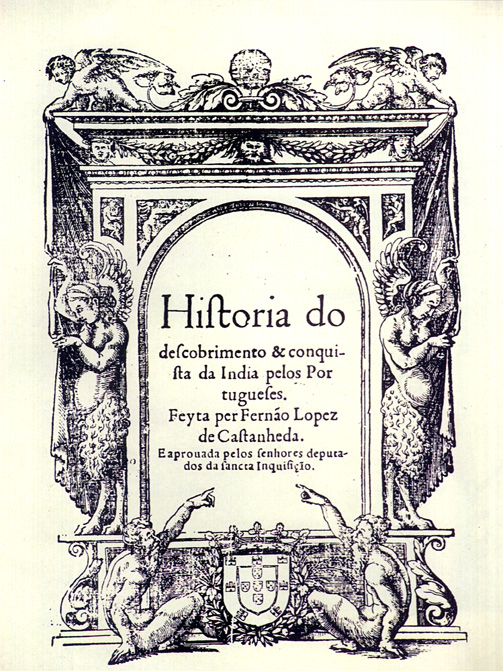

Frontespiece -- First edition.

Hi∫toria do / de∫cobrimento & conqui- /∫ta da India pelos Por / tugue∫es. / Feyta per Fernão Lopez de Ca∫tanheda. / E aprouada pelos ∫enhores deputa- / dos da ∫ancta Inqui∫ição., Coimbra, 1551.

Frontespiece -- First edition.

Hi∫toria do / de∫cobrimento & conqui- /∫ta da India pelos Por / tugue∫es. / Feyta per Fernão Lopez de Ca∫tanheda. / E aprouada pelos ∫enhores deputa- / dos da ∫ancta Inqui∫ição., Coimbra, 1551.

THE CITY OF GUANGZHOU

The Pio sent [Fernão Peres de Andrade] a pilot to guide him to the city of Guangzhou which -- as I said -- is up river, a pleasant sight indeed for its many islets. Some of them are under water at high tide. The {islets} are covered with lush green grass and offer good pasturage to a massive number of adens (Anatidae) and ducks which are taken there in large barges with a great cage looking like a house with a single door through which the Anatidae and ducks fly out. When its time to retire, these are gathered by the sound of a bell, there being one on every barge. And the animals can recognize so well the sound of their barge's bell that even if four bells are ringing at the same time they always rush to theirs. Along both left and right shores of this river there are many walled properties as well as many farms, kitchen-gardens and parklands, all the land being so carefully used that it supplies an abundant {diversity of} provisions. Nearing the city the river is as wide as a cannon shot, 41 and in between three to seven fathoms being deep enough to berth large junks.

The city overlooks {the river}. Its perimeter is broader than Evora, its surrounding walls being five fathoms wide apparelled in soft redstone. [The wall] is filled in with rammed earth up to half its height being always neatly weeded by order of the city council. This wall is crowned with battlements and crenellations, comprising seventy eight towers along its perimeter, all equally filled in with rammed earth. {In each tower} stands a guardhouse with a mast where a flag is hoisted during particular festivities. The enclosure is pierced by seven gates and within the depth of its walls, each gateway has four doors in sequence, being one before the other, from the first to the very last. And on each side of every doorway, which are lined with iron {sheets}, there is a wicket. Despite all, these gates are more beautiful than strong. They are crowned by ample lookout posts which can house as many as five hundred men and where they store their defensive and assaulting weapons for continuous protection of the gates, day and night.

The inner elevation of the city wall is not so well kept as the outer elevation. Because of {the wall's} great width it was necessary to fill it in with rammed earth -- as I have already mentioned -- the excavation for which created a massive and very impressive moat, flooded near the river but not inland as the wall runs uphill to heights that water cannot reach. This moat is crossed by seven bridges, each one corresponding to one of the city gates, all of grand dimensions and well engineered, giving access to two thirds of the city. {Apart from its surrounding city wall} there are no other fortifications besides the residential precint of the Pochanssi who becomes governor when the Tutan is away.

This [residencial precint] looks like a stronghold but is not in fact, because it is a single story high, much like in any other {Chinese} city. The [houses within this comnpound] are all made of mud bricks plastered over42 on the outside with an oyster shell mortar, and lined on the inside with thick handsomely painted planks of wood. {All houses} have shrines with retables and figures of Chinese idols, courtyards lined with beautifull stones, wells with unpolluted water and the more dignified of them, shady trees by the entrances. The city provides much accomodation for its government officers, all being extremely pleasant. All streets have portals at either end. They look like triumphal archways, made of extremely well carved and painted wood. There are more than five hundred of these. 43 This city also has many varelas --which are the praying halls of the Chinese --, as well as mosteiros (monasteries) and igrejas (churches), all with many extraordinary ponds.

This metropolis has a suburbia more densely populated than its walled city centre, streching thinly for miles on end. Both here and the walled city centre are inhabited by countless people, fidalgos which in the Chinese language are called mandarins, 44 as well as merchants and craftsmen. {In this city} can be found such splendid things to buy that are an astonishing delight. By order of the city council the town gates close at dusk because of its many robbers. And on this account as in every other [the city] is so well governed that is has no cause to envy others in Europe. The law of the kingdom does not allow any foreigner to enter within the city walls, except being a Chinese citizen. This is one of the reasons why its suburbia is so densely populated, both the river and the moat being continuously {congested } with more than ten thousand large paraus (embarkations) full with people, many being their {sole} abodes, in such a way that it seems that there are as many people on the river as in the {walled} city, because they cover everywhere. And indeed it is a great marvel that this place is free of plague, wars and hunger. 45

Translated from the Portuguese by: Fiona Clark

For the Portuguese text, see:

CASTANHEDA, Fernão Lopes de, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., História do Descobrimento e Conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses: Livro IV, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.45-49 -- For the Portuguese modernised version by the author of the original text, with words or expressions in square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese text, see:

CASTANHEDA, Fernão Lopes de, ALMEIDA, Manuel Lopes de, 2 vols., História do descobrimento e conquista da Índia pelos Portugueses, Porto, Lello & Irmão, 1979, vol.1, pp.912-914,918-919 -- Partial translation.

*Translator's note: Words or expressions between curly brackets occur only in the English translation.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that in Fernão Lopes de Castanheda's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp.48-49.The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics《""》-- unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated.

1 Many sixteenth century authors used the placename "Espanha" ("Spain") when making reference to the Iberian peninsula as a whole. Luís de Camões (° ca 1524-†1580) the greatest Portuguese writer of all times, was no exception to this rule.

2 Contrary to the author's statement, ambergris is an internal secretion of the sperm whale extremely difficult to obtain in China, but much sought after by the rich people for its believed rejuvenating properties.

3 "cava[s]" ('furrow' or 'trench'): 'fosso[s]' ("moat[s]").

4 Sixteenth century writers systematically looked for analogies between Europe and all the new territories discovered by the Portuguese maritime expansion. For instance, any religious practice which might resemble a Catholic act of cult was immediately believed to be and altered vestige of ancient local Catholic faith, aledgely propagated by St. Thomas the Apostle.

5 The Chinese worshipped a supreme principle called Tian (Heaven/God) which is basically equivalent to the Western concept of Heaven. [sic]

6 "advogada" (lit. 'advocate' or 'intercessor'): 'protectora' ("safeguardian").

7 "Nama" [original Port.] ("Nama") Tianfei; [Chin]: the Portuguese transcription of "Ama" ("Nima") [sic] or 'Heavenly Princess', the Buddhist Goddess of the seafarers, a divinity greatly worshipped in the coastal regions of Guangdong province. According to a number of scholars the name of this divinity is closely connected to the toponym 'Macau'.

8 "Conhãpuça" [original Port.] ("Conhãpuça"): the Portuguese transcription of "Guanyin pusa"·("Our Lady of Misericordy") or 'Avalokitesvara', a great divinity of Buddhism widely venerated in China in the sixteenth century.

9 "varela[s]" [original Port.]("varela[s]"): a pagoda or a Buddhist temple

10 A curious reference to ancient Egypt which confirms the erudite and humanist readings of the author.

11 A curious analogy between Latin -- the common contemporary European language for scholarly, scientific and religious subjects -- and Guanhua· ('Mandarin'), the official government 'language' in the Empire of China.

12 "crasta[s]" [original Port.]: might be a mistake on the part of the copyist and should read 'claustro[s]' ("cloister[s]").

13 This is the first passage in Portuguese language which mentions the Buddhist religion. The author's systematic comparisions between Buddhist and Catholic practises might derive from having collected such information from Jesuit missionaries.

14 Several coeval Portuguese chroniclers equally remark on tonal similarities between the Guangdongnese dialect and contemporary German.

15 The Renaissance concept of the specific attributes which characterize an urban person (i. e., Port.: 'polícia'; or, an inhabitant of the polis) is akin to the present notion of "civility" or "courtesy".

16 "pratéis" [singular: 'pratel'] ('small dish[es]'): meaning 'prato[s] pequeno[s]' (lit.:'small plate[s]' or "plate[s]").

17 The fact that the author mentions in this passage a "garfo" ("fork") but not 'chopsticks' seems to indicate that he has never been in China.

18 "corselete[s]" ("corselet[s]"): a modified corset of leather or steel, worn to protect the chest.

19 "terçado[s]" ("[...], short sabre[s] [...]").

20 "Filho de Deus e Senhor do Mundo" ("Son of God and Lord of the World"): in effect, one of the traditional titles of the Emperor was that of "Heavenly Son", a direct reference to the divine embodiment of his sovereign titularity.

21 Reference to the powerful eunuchs who held high positions in the Chinese government and played important roles in the Imperial Court, traditionally acting as intermediaries between the Sovereign and the government ruling bodies.

22 The first reference in Portuguese language to the Forbidden City.

23 Tomé Pires erroneously mentions in his The Suma Oriental that "The kings of China do not succeed from father to son or nephew, but by election in council of the whole kingdom." It is interesting to compare the sayings of these two authors with Luís de Camões' verses in Os Lusiadas (The Lusiads) (See: Text 1 -- Tomé Pires). Each Chinese dynasty had its specific method of succession, it being not altogether unsual to consider several candidates as potential heirs apparent.

24 "anda[s]" (lit.: 'portable[s]' or 'carrier[s]'): meaning, 'liteira[s]' ("palanquin[s]" or 'sedan chair[s]').

25 The author's remarks on the contemporary strict prohibitions which ruled out possible communications between Chinese citizens and foreigners. Nonetheless, the Imperial Decrees issued to reinforce such restrictions were not allways fully respected in the border regions of the Empire, the Portuguese coming to benefit greatly from such lack of enforcement.

26 The "[...] ilha da Veniaga, • [...]" (lit.: "[...] island of Trade [...]") has been identified by some as Tamão [Port.] or Tunmen [Chin.], but it is more probably a reference to an indeterminate island along the coast of Guandong• province where trade happened to be made, mainly with the Guangzhou• merchants, during a particular voyage. (See: Text 1 -- Tomé Pires)

27 "colou[s]" [original Port.] or 'colau[s]' [Port.] ("Colao[s]") = gelao • [Chin.]: the 'First Secretary of State'. There were six gelao each being a president of one of the liubu (Six Tribunals), the supreme legislative entities of the Empire which acted under direct orders from the Sovereign.

28 "tutões" [Port.] [singular: 'tutão'] ("Tutan[s]") = dutang• [Chin.]: the Viceroy or governor general of a Chinese province.

29 "anchaci[s]"·[Port.] ("Anchassi[s]") = anchashi• [Chin.]: judge of a Chinese province.

30 In theory, access to government posts was open to any citizen who would sit and pass prescribed official exams, irrespectively of their social origins.

31 "conquões"• [Port.] [singular: 'conquão'] ("Conggnan[s]") = zongguan •[Chin.]: the exchequer of a Chinese province.

32 "compins"·[original Port.] [singular: 'compim'] or 'chumpins'• [Port.] [singular: 'chumpim'] ("Chumpim[s]") = zongbing •[Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's armed forces.

33 "ceiui"·[original Port.] or 'ceui'· [Port.] ("Yussi") = yushi· [Chin.]: an official censor invested with the duties of an Imperial itinerant commissioner.

34 "puchanci[s]"·[Port.] ("Pochanssi[s]") = buzhengshi •[Chin.]: the treasurer of a Chinese province.

35 "amechaci[s]"· [Port.] ("Amechassi[s]") = amechashi [Chin.]: probably, a variant of the post of buzhengshi.

36 "tuci[s]"·[Port.] ("Tussi[s]") = dushi·[Chin.]: high officer of a Chinese province's armed forces.

37 "itao[s]"·[original Port.] -- probably a variant of 'aitão' [Port.] ("Aitan[s]") = haidao• [Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's coastal defense forces with powers of jurisdiction upon foreigners.

38 "pio[s]"· [Port.] ("Pio[s]") = beiwoduzhihui ·[Chin.]: the head of a Chinese province's coastal defense forces.

39 "tico[s]"·[Port.] ("Tico[s]") = tiju ·[Chin.]: the supervisor of a Chinese province's foreign trade bureau.

40 The rank of a mandarin [Chinese government official] could be identified by the insignia worn in his garnments and a number of qualifying attributes, such as his belt, his hat and its distinctive lateral flaps, his parasol, the prescribed number of attendants, etc. -- which varied according to status within the official hierarchy.

41 "berço" ("falconet[s]"): a contemporary kind of cannon, or "[...] a small field-gun in use till the sixteenth century."

42 "acafelada[s]" (lit.: 'hidden' or 'concealed'): meaning 'rebocada[s]' ("[...] plastered over [...]").

43 The author makes reference to the pailós [Port.] or pailou [Chin.]: a kind of eavily ornamented triumphal arch or gateway, erected in honour of important past and contemporary local people.

44 In spite of the expressive adequacy of the analogy the author must certainly have been aware that the rank of mandarin [Chinese government official] was not hereditary. It is interesting to observe that, contrary to what the author seems to imply, the word 'mandarin' is not related to Chinese terminology but seems to derive from the Sanscrit, a widespread language in all southeast Asia common in all the contemporary Portuguese posessions and ports of call.

45 The enthusiastic literary rendering of the author is shared by other contemporary Portuguese chroniclers. Nonetheless, Lopes de Castanheda is mistaken about the apparent prodigious profligacy of the Empire of China, demystified a few decades later in the narratives of the first Jesuit missionaries who experienced China from within. (See: Text 8 -- Duarte de Sande)

start p. 61

end p.