[PROLOGUE]

Western painting and Chinese painting are two widely-differing artistic genres. They exhibit different notions as to the process of creation, different methods of expression and exploit different instruments and materials. Thus, they produce different styles and forms.

Nevertheless, the art theories and aesthetics of both reveal similarities and they both share a common human desire to pursue and appreciate the beautiful. On this basis, therefore, there is room for Western and Chinese artists to learn and draw inspiration from one another, and these exchanges can play a positive role in the continuing prosperity and progress of human society.

Up until now, Western painting, particularly the history of oil painting, has been largely ignored in Chinese art theory and barely mentioned in the curricula of Chinese art schools and colleges. There only exists a very vague idea and no consensus as to when and from where oil painting was first introduced into China. As an example of the misinformation surrounding this issue, a certain artistic authority, upon witnessing the gravestone paintings excavated at Mawangdui, • Changsha,• claimed that oil painting had in fact originated in China. The gravestone paintings [in question], however, were produced using lacquer and not oil paints.

The idea that oil painting was first introduced into China through Macao was put forward by this writer in August, 1986, at the National Oil Painting Conference •held in Zhuhai.• Bringing together thirty well-known figures from the Chinese art world from all-over the country, including professor Wan Weimo• of the China Fine Arts Society,• professor Zhan Jianjun• of the China Oil Painting Research Institute,• professor Wen Yipeng• from the National Academy of Fine Arts,• professor Guo Shaogang• from the National Academy of Fine Arts of Guangzhou and other delegates representing art circles from all over the country, this notion aroused the interest of all those present.

As yet, no discussion on this topic, be it in Hong Kong, Macao, the People's Republic of China, Taiwan, or anywhere else for that matter, has been undertaken. The reason for bringing up the subject here is to explore the roots of oil painting in China and thereby attempt to solve the query surrounding its origins. The intention is to offer a few comments and ideas to initiate the discussion so that other, more learned, scholars may arrive at more adequate conclusions.

§1. THE INTRODUCTION OF WESTERN PAINTING INTO THE EAST: AN OVERVIEW

Oil painting originated during the European Renaissance with the renowned Dutch painter Jan van Eyck (°ca 1385/1390-†144l) and his brother Hubert (active ca 1426), who painted with dry oils in the manner of tempera painting. As oil painting permits very sophisticated expression, such as the distinct gradation of colouring, texture, coverage, pliability and durability, it rapidly spread throughout Europe, its growing significance culminating in the appearance of such great masters as Leonardo da Vinci (°1452-†1519), Michelangelo Buonarroti (°1475-†1562), Raphael [Rafaello Sanzio] (°1483-†1520) and Titian [Tiziano Vecelli] (°1477-†1576).

Through the increasing overseas presence of Westerners and their pioneering religious missions, it didnt take long for oil painting to be introduced into China. 1 In 1553, the Portuguese arrived in Macao, on the Southern coast of China, and in 1568 the first Catholic Bishop arrived in the territory, establishing, in 1576, the first Catholic Diocese of the Far East, and building its grandest church.

Although scholars have found evidence that missionaries from ancient Rome [sic] had painted Western beauties in Han• dynasty (206BC-AD220) attire, full of primitive simplicity and solidity, on the border of Putian• county, Fujian• province, the true introduction of Western fine art into the Middle Kingdom came in 1581, when the Italian missionary, Matteo Ricci, S. J., arrived in Macao with several Holy portraits painted in oil. That taixi huafa• (Western painting), came to be highly regarded by the Chinese can be seen from the recorded description given to three portraits of The Holy Father [Almighty God] and The Holy Mother [Virgin Mary] presented to Emperor Chongzhen• of the Ming• dynasty, in Beijing twenty years later as tribute. The historical records describe the portraits as: "[...] those of God and a Woman with a Baby in her arms, all with fine, well-defined features, vivid and life-like, solemn and beautiful. They filled Chinese artisan-painters with awe."2

Over the last four hundred years, many Western artists have lived and worked in China. The most influential of these was Giuseppe Castiglione, S. J., (°1688-†1786) [Chin.: Lang Shining],• an Italian missionary. In 1715, Castiglione, who was particularly accomplished at drawing horses, came to China on missionary duties and became a painter for the Imperial Court in Beijing. A collection of his paintings, including such works as "Taishi shaoshi tu"• ("Old and Young Generals") and "Hui Xian Guifei Xiang" ("Portraits of Virtuous Princesses"), is currently to be found in the Palace Museum, Beijing. Records of Castiglione's influence can be found in the Neiwufu dangan• (Inner Archives of the Qing Dynasty). For example, in February, 1736, (Qianlong• reign, year 1) the Annal Records state that the eunuch Mao Tuan• passed on the Emperor's Decree that: "There is to be a painting by Castiglione behind the screen in the Chonghuagong• [Chinghua Palace]." In November of the following year, Mao Tuan also communicated the following Decree: "The Western painter Castiglione is to continue his work in Shouxuan Chunyong• after completing all his oil paintings in the Yuanmingyuan [Summer Palace]."•

We also come across records of other Western painters working at the Imperial Court. A contemporary of Castiglione's, Denis Attiret, S. J., (°1702-†1768) [Chin.: Wang Zhicheng],• a French painter who was an extremely good portraitist and whose work, a series of eight paintings entitled "Menggu Guizu Xiang"• ("Mongolian Nobles") is now in the Kunsthistorishes Museum (Art & History Museum) in Berlin, was mentioned thus: "[...] during Qianlong reign, year 19, in July, the Emperor was pleased to invite the Western painter, Wang Zhicheng to Rehe,• where he completed twelve oil paintings."

Another noteworthy Western painter [to have resided in the Orient] was George Chinnery (°1774-†1852), a British artist who lived in Macao for twenty-seven years between 1825 and 1852. A great master of portraiture and urban and rural landscapes, he was particularly influential on socalled 'Chinese export' painting during the late Qing period. Also worthy of special note are Carl Katherine Augusta (° 1861-†1938), the well-known female American painter who painted the Cixi• Empress Dowager in Beijing, a Japanese painter [sic] who taught Western painting at the Nanjing Teachers' Training School• in 1902, a Frenchman [sic] who taught oil painting in the National Academy of Fine Arts of Beijing• and at the National Academy of Fine Arts of Hangzhou• in the 1920s, a Russian professor [sic] who ran an oil painting class in Beijing during the 1950s and who greatly influenced methods and techniques of oil painting at that time, and Boba [sic], a Romanian painter who ran another class in Hangzhou during the 1960s, and who became renowned for his linear creations.

Although several records of artisan-painters and baoyi• (Manchurian: slaves) being ordered by the Emperor to study oil painting under the guidance of Western missionaries can be found, mentioned is made of Ding Guanpeng,· Wang Youxue,· Wang Ruxue,· Gang Weibang,· and Wang Shilie,· the earliest known oil paintings to have been produced by Chinese artists were finished, at the latest, in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Entitled "Tong yin nu tu"· ("Beauties on the Shade") and currently hanging in the Palace Museum, they comprise eight oil screen paintings of seven noble ladies chatting and playing amongst the trees. At the back of the screens are some poems personally written by Emperor Kangxi· (r. 1662-†1723), help us to date them. These paintings are inferior in quality to work produced by Western artists at the time, revealing somewhat the triumph of ambition over technique.

While foreign artists lived and worked in China, there were in parallel quite a number of Chinese artists studying Western painting abroad. The earliest recorded mention is of Guan Zuolin,· from Nanhai,· in Guangdong· province, a portraitist whose work was described as "[...] life-like and stunning[...]." Becoming known as the pioneer of Chinese oil painting, he studied in Europe and the United States of America at the beginning of the nineteenth century and later returned to Guangzhou, where he set up a studio.

Guan Zuolin was succeeded by Guan Qiaochang, • [pseudonym Lamqua or Lin Gua• (active ca 1820-†1860)], also from Guangdong, who was very actively involved in Guangzhou· and Macao art circles in the middle of the nineteenth century. A student of George Chinnery, he became a very successful imitator of the latter's work and had several of his own selected for exhibitions in Europe and the United States, where he became known as 'the Thomas Lawrence of China'.** He opened a studio in Shisanhang,· Guangzhou, where he hired many artisan-painters. This studio was to become an important base for the late Qing dynasty trade in 'Chinese export' paintings.

Another Chinese painter to achieve notoriety was Li Tiefu• (°1869-†1952), who was born in Heshan,· in Guangdong province. He studied both in Europe and the United States and created some outstanding paintings in oil and watercolour, receiving many prestigious awards between 1905 and 1925. His reputation earned him a position as research fellow at the worldrenowned Royal Academy of Arts in London, the first Asian artist to enjoy such an honoured position, where he remained for ten years. He returned to China in his later years and carried on his work in Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and, amongst others, the provinces of Guangxi· and Sichuan.·

And another was Feng Gangbai• (°1884-†1986), born in Guangdong, who studied at the Academia Real de Bellas Artes (Royal Academy of Fine Arts) in Mexico City, in 1906 and later studied oil portraiture with the famous American painter Robert Henry for eleven years. Together with Li Tiefu, Hu Gengtian• and Gao Jiangfu• he gave financial support to Sun Zongshan's• [Sun Iat Sen] revolution.

The first Chinese artist to study in France, where he arrived in 1911, was Wu Fading· (°1883-†1924). Upon his return to China, he taught oil painting in Beijing and Shanghai. Li Yishi• (°1881-†beteween 1937-1945?), born in Jiangsu, studied oil painting in Britain and pursued his artistic career in Beijing and Nanjing after his return.

Apart from these artists, who represent the leading figures in Chinese oil painting, there have also been many accomplished teachers. The first of whom was Liu Shutong• (°1883-†1942), who studied Western painting in Japan between 1905 and 1910. When he returned to China in, he taught in the cities of Tianjin,· Hangzhou,· and Nanjing,· to name but a few, emphasising outdoor sketching and thus paving the way for the introduction of innovative painting techniques in China.

Another figure was Xu Beihong• (°1895-†1953), born in Jiangsu province. He was the founding father of realism and the most influential and followed teacher of painting in China. Extremely good at sketching, he studied at the Académie des Beaux Arts (Academy of Fine Arts) in Paris in 1918 and then devoted himself to the teaching of fine arts in Nanjing, Shanghai and Beijing after his return to China in 1927. Another is Lin Fengmian• (°1900), born in Guangdong province, who advocated the integration of Chinese and Western art and thus created his own distinctive style. He was admitted to the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris in 1917 and then became Principal of the National Academy of Fine Arts of Beijing and the National Academy of Fine Arts of Hangzhou after his return to China in 1925.

Two others are Liu Haisu• (°1896-†1995) and Yan Wenliang• (°1893). The former, born in Jiangsu• province, opened a school of fine arts in Shanghai in 1912 and established a course in nude drawing which led to heated debate and attracted a lot of attention to the teaching of art in general. Liu went on a study tour of Europe in 1929, which also attracted a great deal of publicity in the Chinese art world. The latter, born in Suzhou, set up the Suzhou School of Fine Arts• in 1922 and went on to study oil painting in France in 1928. He resumed his work as Principal of the Suzhou School of Fine Arts after his return and nurtured a large number of talented artists.

§2. MACAO: THE ORIGINS OF OIL PAINTING IN CHINA

Having looked briefly at the history of oil painting in China, let us consider more closely its origins.

2.1.

There is a tendency among professors of fine art to concentrate on Western oil painting to the almost complete exclusion of its Chinese manifestation. On the rare occasions when the history of the latter is broached, the discussion is generally restricted to the art of Beijing or Guangzhou. Let us then look at these arguments.

Those who maintain that Beijing is the home of Chinese oil painting base their argument on two premises. Firstly, that as Beijing was the capital of the Ming and Qing dynasties, it was the ultimate destination for all foreigners coming to China. As early as the beginning of the eighteenth century, the existence of Western painting had already been recorded in Chinese history books.

2.2.

Firstly, that as Beijing has always been the cultural and artistic hub of China, with the greatest number of outstanding painters, it played a leading role in the spread of oil painting.

Defenders of the Guangzhou argument, however, justify their reasoning on slightly different grounds. As Guangzhou was the earliest Chinese port to have contact with the West, the argument goes that it must therefore have had the earliest contact with Western painting. Further justifications were based on the fact that the largest number of students studying Western painting abroad, among which were some of the best, came from Guangzhou, and the fact that the city was the centre for the late Qing dynasty trade in Chinese portraits for export.

Both these theories, however, are questionable. Firstly, neither Beijing nor Guangzhou were the first places in China to come into contact with oil painting. Historical reasoning supports the argument that oil painting in fact arrived in Macao at least fifty years earlier.

Macao was the first part of China to come into contact with the West. Founded in 1553, two hundred and eighty-nine years before the establishment of Hong Kong in 1842, Macao served the West as its principal trading, religious, cultural and artistic centre in the East, as well as a gateway into China, for three hundred years, and as such, played an important historical role in the development of East-West cultural relations.

2.3.

Secondly, the rise of oil painting went hand in hand with the spread of religion. The founding of Macao coincided with the Late Renaissance in Europe, which fostered generations of great masters who produced many historically unprecedented works. The brilliant achievements of the Renaissance had a great influence on Macao, most obviously within the religious Missions. Successive numbers of European missionaries came to the East, where they established religious centres and churches (such as the magnificent St. Paul's Church) and engaged in Western sculptural arts and painting. Many missionaries, as noted above, were also very accomplished painters.

The Bishopric of Macao set up an embroidery factory and an art studio for religious purposes inside a convent school in the Rua da Praia Grande (Praya Grande Street), where ecclesiastical regalia and religious books for use in the Far East were produced. In the studio, students were taught oil painting techniques called taixi huafa. Though their energies were mainly directed towards producing imitations of Holy portraits and Biblical picture stories, the studio would almost certainly have been the earliest school in China dedicated to training artists in the skills of oil painting. Not only could Western missionaries be found working in the studio, but also many Chinese and Japanese devotees working as artisan-painters, whose works can still be found today in the Seminário de São José (St. Joseph's Seminary) in Macao, although most have been damaged or destroyed due to fire or the ravages of time. As with the mural paintings of Dunhuang• or in some Chinese temples, however, no personal markings were left by the artists so it is impossible to attribute them.

2.4.

Thirdly, then, Macao is home to a series of the earliest oil paintings imbued with both Western and Chinese cultural characteristics to have been produced in China.

From late Renaissance mural paintings evolved easel paintings. The paintings thus created were of course still quite basic in style, expression and colouring and no match for the works of the great European masters. But, despite a distinct immaturity, there is quite obvious assimilation of Chinese and Western characteristics both in style and technique, proving that once Western painting was introduced into the East, Oriental influences and features were quickly absorbed. Conversely, the assimilation of Western artistic characteristics into Chinese culture would then represent the very starting point of Chinese oil painting. The work created at the Church run studio served as the basis upon which Chinese oil painting with Chinese characteristics would ultimately be founded.

Of these paintings, that which is of most historical significance and artistic value is "Xunantu" (lit.: "The Martyrdom"), *** which is presently in the possession of St. Joseph's Seminary, in Macao. Painted by an unknown Japanese Catholic devotee while living in Macao, and completed in 1640, it depicts the crucifixion of some twelve**** Catholics in Japan towards the end of the sixteenth century in a scene of the most spectacular tragedy. Having freed himself from imitating Holy portraits and representations of Biblical stories, the artist, emotionally-charged, and full of the humanistic ideals and fraternity of the new rising trading classes, set about the task of reflecting social realities and of voicing indignation against the cruelties of the Japanese feudal rulers. Viewed from an artistic point of view, the painter has successfully managed to both create an atmosphere and plot and combine Oriental and Occidental techniques.

2.5.

Fourthly, the first Chinese painter we know of by name to have come into contact with Western painting was Wu Li (°1633-†1718), who studied Western painting in Macao. Although, as mentioned above, a group of Chinese artisan-painters were trained by the Church in Western techniques earlier, their names, unfortunately, have been lost to us. Wu Li came to Macao during the early Qing dynasty. One of the Liu Dajia• (Six Masters) of the early Qing dynasty, he was converted to Catholicism in 1682 at the age of fifty. He immersed himself in religious learning at St. Paul's College for six years, completing a collection of poems under the title Sanbashi• (Poems on St. Paul's) and getting into closer contact with Western painting thirty years before the arrival in Macao of Giuseppe Castiglione. Wu Li's style changed dramatically after being exposed to Western painting. He started to pay a lot of attention to contrasts in light, distance, colouring, size, perspective, texture, etc., and created a unique style called 'yang mianzhou'• (lit.: 'creasing on the bright side'), which led to him becoming the most accomplished and individualistic painter of the early Qing dynasty.

Although much has already been said on the subject of Wu Lis work, one point is worth repeating. In his "Huairong tangtu"• ("Pagoda Tree Temple"), the house shaded by lush trees is only faintly visible, but it is set off by the light and colour of its surroundings. This approach and treatment, rare in traditional Chinese painting, was obviously influenced by Western painting, although Wu Li may not himself have agreed with this. In comparing his works with Western painting, and revealing his views on the latter, stressing that there were many important differences, he once said: "I do not ape or imitate, or follow any beaten track. I follow my own mind [...]. My brush dashes and flies as I wish [...]."3

2.6.

Fifthly, the first Chinese painter to be recognized and lauded in Western artistic circles was Guan Qiaochang, one of George Chinnery's best students, trained by the latter in Macao. Acclaimed as 'the Thomas Lawrence of China', he was an outstanding oil painter of the earliest period. His work was highly sought after by the nobility and wealthy merchants and was exhibited in both Europe and the United States. Around 1870, the Western columnist and photographer John Thompson took a picture of him which was included in an album published in London in 1873 entitled Illustrations of China and Its People. In the caption of the illustration, Thompson wrote: "Lumqua [Guan Qiaochang or Lamqua] was one of George Chinnery's Chinese apprentices. Lumqua produced a considerable number of fine oil paintings which are still copied these days by lesser painters in Hong Kong and Guangzhou. Had he lived in another country, he would have been master of his own school. These days, his Chinese followers copy his work because they are highly praised." Indeed, Guan Qiaochang played an important role in promoting Western painting in China, particularly works from Chinnery's workshop and apprentices of the so-called 'Chinnery School'.

2.7.

Sixthly, Macao was the base for the trade in 'Chinese export' paintings during the late Qing dynasty and it was in Macao that Westerners purchased Chinese paintings on a large scale.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Macao, which was not only a prosperous trading centre but also a busy market-place and export base for paintings and artistic souvenirs, was being visited by ever-increasing numbers of European and American trading vessels. As insufficient numbers of original paintings existed to meet the growing demand, increasing quantities of duplications were produced. Chinese paintings for export became standardized to cater to the taste of curiosity-seeking Westerners, thus trivializing the whole artistic output. Great demand grew for portraits of Chinese Emperors, royal beauties, images of exotic customs, seaports, temples and pagodas, etc. painted in Western styles and techniques (oil, watercolour, gouache, and other media) acceptable to Western buyers. However, there was a positive side to this trend: at a time when photography had yet to be introduced into China, these paintings constitute a true record of images and customs from Macao, Hong Kong, [Guangzhou] and Guangdong from a period more than a hundred years ago. Moreover, amongst those paintings exported were some of genuinely high quality, showing that Chinese artwork of this nature had become sought after in the West because it had reached an acceptable standard; a remarkable achievement by any criterion. In a country where the predominant art form for thousands of years had been traditional Chinese painting, it was not easy for Western art to find a niche. That it did, could only have been achieved first in Macao. This itself is strong evidence to support the view that Macao was the conduit into China for Western painting and thus lies at the very heart of the origins of Western painting in China.

2.8.

Seventhly, the techniques and skills of oil painting spread gradually northwards from Macao to Guangzhou and Shanghai, and then to other parts of China. Although the oil paintings brought into China by European missionaries were restricted to religious circles, commercialized art, painted in oil, water-colours and gouache, together with Western painting theories and techniques, spread like a rising tide northwards from Guangzhou to Shanghai and then on to the other city ports of China. For example, in 1852, foreign missionaries opened studios in Xujiahui,· Shanghai, recruited a hundred or so orphans, taught them the art of Western painting and turned out a large number of religious paintings. Thus the art of oil painting spread from the small number of Western painters to Chinese painters and from church studios to folk shops. It came to cover not only holy imagery but imagery of every kind, and it grew from the creation of single paintings to the large-scale duplication of many. When Westerners became interested in buying, and the Chinese in appreciating, machines were used to churn out large quantities. At first, only Catholic devotees and some individuals studied Western painting, but later the state sent students abroad to specialize, as, for example, happened in 1905, when the Qing government dispatched Li Shutong, Zeng Xiaogu• and many others to Europe.

Finally, and this is a very important point which is often neglected or misunderstood, Macao has always been under Chinese sovereignty, 95% of its population is Chinese and Chinese culture has always prevailed.

CONCLUSION

Although this theory may be regarded as controversial by art historians and scholars alike, both overseas and in China, the hope is that, whatever the consequence, it will generate interest in this so far unmapped area.

One cannot forget Macao when discussing Chinese culture and arts. From its roots in Macao, oil painting has blossomed throughout China during the past two hundred years, and especially during the past two or three decades, during which time it has developed into a genre second only to traditional Chinese painting.

Much work on the history of the fine arts in China exists, but it deals exclusively with traditional Chinese painting. Though oil painting is an imported genre, it is extremely widespread in China today, and research into its introduction, development, differing styles and techniques and its history and national characteristics is of academic value.

Furthermore, research into the expansion of Western painting in China is not only significant for the development of cultural and artistic exchange between the East and West, but also bears profoundly on Sino-Portuguese, Sino-Italian [Sino-French] and Sino-British relations. Art transcends national boundaries, serving as a means to better communication and understanding; it is spiritual wealth created by and shared by all humanity.

Translated from the Chinese by: Ieong Sao Leng, Sylvia 杨秀玲 Yang Xiuling

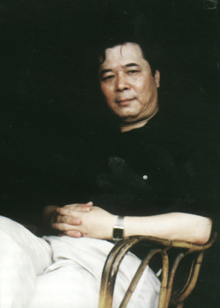

LI RUIXIANG 李瑞祥(°1941).

An Apparition Goddess Ama, Protectress of Seafarers 澳门开埠流妈祖护航的故事- MACAU 即“妈阁”之音译。

LIRUIXIAMG 李瑞祥(°1941).

1992. Oil on canvas. 25.0 cm×18.3 cm.

Yin Guangren and his Successor Zhang Rulin, Magistrates of the Qing Court in Macao and Authors of the Monograph of Macao (completed in 1751)清朝首任澳门同知印光任与后任张汝霖合撰。

LI RUIXIANG 李瑞祥(°1941).

1995. Oil on canvas. 25.0 cm×18.3 cm.

**Translator's note: Thomas Lawrence (°Bristol, 1767-†London, 1830), a renowned British portraitist, royal painter and President of the Royal Academy of Arts, London.

Translator's notes:

*** Better known as "The Martyrs of Japan".

**** In fact, twenty six.

NOTES

1 JIANG Shaowen 姜绍闻, Wusheng shishi 无声诗史 (The Silent Epic).

2 TAI Changan 泰长安, Meishu Shilun 美术史论 (A History of Fine Arts), 1985, vol.4.

3 ZHOU Jiyin 周积寅 et al, Jiangsu lidai huajia 江苏历代画家 (Painters of Jiangsu).

* Born in Guilin,• the People's Republic of China. Represented China at the "International Exhibition of Children's Paintings" in Budapest, in 1952. Enrolled at Zhongnan Art School,• in 1957. Graduated from the Department of Oil Painting at the National Academy of Fine Arts of Guangzhou,• in 1965. Secretly destroyed hundreds of his artworks during the Cultural Revolution. Became resident in Macao, in 1982. Held his first individual exhibition in Macao, in October 1983. In the past decade, has devoted himself to painting images of, and from the history of, Macao.

start p. 203

end p.