§1.

It is not a coincidence that the Fifth Centenary of the Discoveries, the Five Hundredth Birthday of Ignacio de Loyola (1491-1991), the Commemorations of the Establishment of the Society of Jesus, (1540-1990), 1 as well as the arrival of the first Europeans (Portuguese) in Japan (1543-1993), were all held in the above years.

The Society of Jesus was related to the Discoveries since their early days. In the first years of the Society, the Pope sent its first missionaries to Portugal and shortly afterwards Fr. Francis Xavier left Lisbon for the Eastern Indies. Therefore, the arrival of the first Europeans (Portuguese) in Japan in 1543, nearly coincided with the arrival of Francis Xavier and his companions, Fr. Cosme de Torres and Br. João Fernandes in Japan in 1549.

In the light of the above, it would be worth mentioning Fr. Luís Fróis. 2 In a letter dated 25th October, 1585 written in Nagasaki, Fróis addresses Father General Claudio Acquaviva:

- "I came from Portugal to India in the early days of the Society and before Father Francisco arrived in Japan for the first time; I was brought up at Goa's School with the 'cream' of his holy doctrine."3

In 1548, Fróis arrived in Goa, one year before Francis Xavier departed to Japan. Luís Fróis goes to Japan fourteen years later, in 1563, still in the early stages of the Jesuit mission on the above archipelago. Fróis who quite rightly was called the 'Father of Japanese Sciences' (Japanology), 4 was already known by those who studied the Jesuit activity and the 'old' Church in Japan, but he was not given the credit his work is worthy of until recently. In his book titled Figuras de Silêncio (Figures of Silence), dated 1981, the Portuguese writer Armando Martins Janeira refers to Luís Fróis as "[...] a classic yet to be explored."5

Most likely Luís Fróis was born in Lisbon, in 1532. 6 From documents contemporary with other Jesuits we learn that Fróis studied at the Royal Office "[...] que ha sido hombre de palacio, de que aún tiene [- that is, in India -] algunas hezes."7 We know less than nothing about his youth. In 1548, at the age of sixteen years old he joined the Society of Jesus and in the very same year he left for and arrived in Portuguese India. Until 1563 he visited Goa and other Indian cities but between 1554 and 1557 he was stationed in Malacca. As mentioned earlier, Fróis met Francis Xavier in Goa prior to the latter's departure to Japan and met Fancis Xavier after he returned to Goa from Japan in 1552. Francis Xavier's reports on Japan may have caused a strong impact on Fróis. From Japan, in a letter dated 1564 Fróis writes that"[...] very often Father Xavier told me that there is no other people willing to accept Christianity than the Japanese." Still in Goa he collected information on Japanese culture and civilisation. It was then that he developed a strong desire to go to Japan. It would be worth mentioning that eventually Góis met Fernão Mendes Pinto, the author of Peregrinação (lit.: Pilgrimage, or The Voyages and Adventures [...]). Fernão Mendes Pinto wrote a long and impressive letter8 that gave us clues on the style of the book which later made him famous. I find it quite possible that Fróis was impressed and somewhat influenced by such a descriptive and lively style of Fernão Mendes Pinto's letter and speech after exchanging views in Goa and/or on the way to Malacca. 9

Fróis, who at the time was known as Polycarpo10 started his literary career in Goa with a Carta Annua (Anual Letter) in which he reports on the Indian mission. Such a letter was written under the orders of the Rector of the Jesuit College in Goa and Fróis finished it on 1st of December 1522. 11 In that letter and in those that followed a style and writing featuring "[...] more horizontal than vertical description [...]" is already present. 12 The whole development of the Age of the Discoveries' literature and mainly of those writers who wrote in foreign countries featured the same phenomenon to which Donald F. Lach, an American professor, refers as a development into "[...] chronicle narrative [...]."13 According to Donald Lach, Portuguese historians could no longer write contemporary history based upon classic models such as Titus Livius (°59 BC-†AD 17) or Thucydides (° ca 460-† ca 400 BC). 14 Overseas news called for proper treatment and a political-geographical-cultural description of foreign places was more and more important to understand what was happening. Luís Fróis' letters from India and mainly those written from Japan are a good example of that development.

Historia de Japam (History of Japan) was written on an yearly basis rather than on decades and this was explained by Fróis in the Prologue to Historia de Japam as he knew that describing Japanese culture and civilisation background was required if one was to understand historical events:

"One of the things I thought was necessary in History was to clear as much as possible all ambiguities and misunderstandings which give Europe a wrong idea of what things really are here in Japan and were passed in letters written throughout the years by our people here. I believe that the various concepts were caused by ambiguous words written in letters without clarifying their meaning. If we can be more precise at least readers in India or Europe are aware that anything so excessively described as to raise doubts may be explained by the lack of proper wording [...]."15

Fróis then gives ten examples in this paragraph and stresses that he Japanese 'world' is difficult to understand by those readers who only know Europe but such a 'world' is also difficult to be conveyed through the traditional means available to writers.

In 1563, Fróis arrives in Japan as he himself reports in his Historia de Japam:

"On the 6th of July 1563, Dom Pedro da Guerra arrived at Yokoseura port together with Father Luís Fróis, Portuguese, and Father João Baptista de Monte [Giovanni Battista del Monte], Italian."16

Therefore, Historia de Japam is one of the most important sources of his biography. He also reports in Historia de Japam that some weeks after his arrival he had to retreat to Yokoseura city because of Japan's internal political environment. 17

Fróis arrived in Japan in one of the most crucial moments in Japanese history as over the last hundred years continuous civil wars broke out. As Francis Xavier recognised the Emperor did not have the least political strength and the power of the last Xoguns of the Ashikaga dynasty (1338-1573) was declining rapidly. Lacking a central power, the Japanese daimyo (lit.: "Great Name" - of many of Japan's sixty six provinces but referred to by the Portuguese in their chronicles as "reis" ("kings")) tried to get hold of as much power in their region. And to achieve that they involved in alliances and treason. Luís Fróis describes the situation of that time which in Japanese is known as 'gekokujo jidai' ('reversal of social strata'), in Part II of his Historia de Japam as follows:

"Things here are very unstable because one does not know what will happen tomorrow; there is no safe place because turmoil is widespread."19

He also explains how the mission was involved in the internal Japanese politics and how it depended upon the current conditions:

"Disturbances pose major obstacles to converting pagans and maintaining Catholics; Fathers are quite frustrated because when they are about to reap what they have sown a riot suddenly erupts and everything just disappears [...]."20

Similar conditions prevailed when Fróis arrived in Japan, in 1563, more precisely at Yokoseura in Hizen province. Its daimyo was Dom Bartolomeu Omura Sumitada (°1532-†1587). As implied in Historia's last section he backed the mission for commercial reasons as he knew that the annual man-of-war Portuguese ships and their traders very often chose harbours where Jesuit missionaries were stationed. However, to missionaries Dom Bartolomeu was very important because he was the first daimyo to be baptised in Japan - in May 1563. 21 Jesuits saw this as a major political, cultural and social support. One can compare the conversion conditions mainly in Southern Japan with conditions after the Habgsburg Edict Cuius regio, eius religio.

Also in 1563, Dom Bartolomeu's non-Catholic vassals talked his political contenders into rebelling against him. This rebellion was no different from any rebellion of that time but Dom Bartolomeu's enemies based it on his conversion to Catholicism. Fróis reports that vassals opposing him wrote a letter to his enemy:

"[...] how could he accept such an injustice and abhorrence as explained by the fact that having been adopted by his mother to inherit that state even though he was not born there, Dom Bartolomeu not only failed to pay respect to his father's statue and image by burning them, but also allowed new and foreign laws in his land?"22

Dom Bartolomeu's retreat from his castle was the reason why Fr. Cosme de Torres decided:

"[...] to order Fr. Luís Fróis with Br. João Fernandes to stay on Takushima island for a while until a door or mission was open where they could be sent to."23

On Takushima islet, Fróis started learning Japanese more steadily:

"[...] he started with Brother João Fernandes learning the first gram-mar ever written in Japan, its verb inflections and syntax, as well as some vocabulary [...]."24

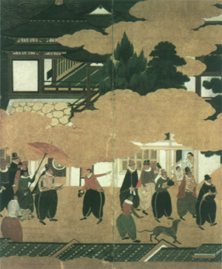

A pair of six fold Japanese screens - detail.

Attributed to KANO DOMI. Kano School. ca 1593-1600.

Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 172.80 cm x 380.0 cm.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon - Permanent loan from the Ministério das Finanças (Ministry of Finance), 1952.

"The painter clearly depicts the hierarchy of the advancing procession: the [Portuguese] Captain-Major recognisable by the protective state parasol wears rich ornaments and dazzling daggers. Both he and the other officers wear the famous bombachas (large baggu trousers used by the Portuguese in the East) and their doublets are fronted with metal buttons, previously unknown in Japan. They are surrounded by sailors, African slaves, Indians and Malays."

In: PINTO, Maria Helena Mendes, Biombos Namban/Namban Screens, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, p.40.

A pair of six fold Japanese screens - detail.

Attributed to KANO DOMI. Kano School. ca 1593-1600.

Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 172.80 cm x 380.0 cm.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon - Permanent loan from the Ministério das Finanças (Ministry of Finance), 1952.

"The painter clearly depicts the hierarchy of the advancing procession: the [Portuguese] Captain-Major recognisable by the protective state parasol wears rich ornaments and dazzling daggers. Both he and the other officers wear the famous bombachas (large baggu trousers used by the Portuguese in the East) and their doublets are fronted with metal buttons, previously unknown in Japan. They are surrounded by sailors, African slaves, Indians and Malays."

In: PINTO, Maria Helena Mendes, Biombos Namban/Namban Screens, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, p.40.

Fróis reports that in his first years in Japan he also learned a Buddhist text, a very difficult text. 25 We do not know the level of Fróis' knowledge of Japanese or Sino-Japanese writing. However he was fluent in spoken Japanese. 26 During the first visit of Father Inspector Alessandro Valignano he was his interpreter and we also know of many conversations that Luís Fróis held with the most important personalities of that time, Generals Oda Nobunaga (°1534-†1582) and Toyotomi Hideyoshi (°1536-†1598) who enjoyed their relationship with Fróis also because of his Japanese language fluency. As noted by Japanese Profs. Okada Akio and Matsuda Kiichi, Luís Fróis not only related with the most prominent personalities of that time but he also dealt with all social classes. 27 His own history gives us evidence of that.

Fróis arrived in the capital of Japan, Meaco [Miako, Myako, etc.] (presently Kyoto) in 1565. Despite being located in a state going through one of the worst periods in its history, it had been the nation's capital of art, culture and intellectual life. In three letters dated February 20th, March 6th and April 27th 1565 written soon after he had arrived in the capital, one can see traces of what would become the most important Western chronicler of Japan of that time: Luís Fróis.

The aforementioned three letters could be found in the famous edition of Cartas que os Padres e Irmãos da Companhia de Jesus escreverão dos Reynos de Iapão e China [...] (Letters Written by the Fathers and Brothers of the Society of Jesus from the Kingdoms of Japan and China [...]) which were published in Evora in 1598. 28 In those letters Fróis shows his admiration for Japanese culture, for in-stance as regards its architecture which he thinks is as good as the European. 29 He shows interest in Japanese civilisation through very detailed descriptions. Nevertheless, those letters show the limitations of his enthusiasm when describing the Japanese religious life and Buddhist clergy who happened to be the strongest opponents of missionaries in Japan. 30

Luís Fróis' letters from Japan are important to know him as the historian of Japan. In terms of quantity and quality they are far better than other contemporary Jesuits in Japan until late sixteenth century. And the best document was the publication of Cartas [...] de Iapão e China [...]. Donald Lach says: "The superior quality of the letters from Japan can probably be attributed to the fact that most of them were written by Luís Fróis, one of the ablest observers and chroniclers ever to be associated with the Society [of Jesus]."31

Thanks to its letters from Japan Luís Fróis was seen as a very talented writer both by his superiors in the Society of Jesus and the public.

Since 1565, Fróis wrote his letters every year until he died in 1597. During the period when Alessandro Valignano was Visitor of Japan for the first time between 1574 and 1582, he directed that official letters be written every year by the Japanese Mission. 32 Fróis wrote the most important Cartas Annuas (Annual Letters) from Japan between 1579 and 1597. As stated earlier, Fróis' letters were known al around Europe. In fact there are Fróis' letters or reports translated into French, Italian, Castilian, German and Latin.

Based on his reputation as the writer of letters of the Jesuit's oriental mission, Rome superiors directed Fróis to write the history of Jesuit activity in Japan which would be included in a major history of the Society's activities all around the world. Josef Wicki, publisher of the Portuguese edition of Historia de Japam, published by the Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa (National Library of Lisbon), 33 states the following in the Introdução (Introduction) to the first volume:

"In 1579 P. J. P. Maffei was in Portugal searching for documents and material to write his history of Eastern India. While doing so, he proposed to Father General Mercuriani that Father Fróis, a very talented writer living in Japan who was also very experienced and skilful, was asked to write a "commentary" on the progress of the faith in that country, describing its environment, government and wars that have hindered Christianity."34

Thanks to this Luís Fróis started writing Historia de Japam an official work that he accepted in the early 1580's after living in Japan for nearly twenty years. He kept writing it until he died in 1597.

Towards the end of 1586 he finished Part I of Historia de Japam35 which in its one hundred and sixteen chapters covers the mission expansion and the events of the Jesuit Province of Japan between 1549 and 1578, in other words the history of "[...] the first phase of Japanese conversion [...]" as he himself puts it (I would like to point out that the Jesuit Mission history in Japan may be divided differently). He also wrote an introduction to Historia de Japam featuring37 chapters on Japan's qualities and habits. Only the abstract headings are known from this introduction. 36

Between 1592 and 1593, Fróis completed Part II of Historia de Japam which describes the events occurred until 1589. In the Prologue to Part II Fróis writes the following:

"In this Part II [...] I would like to report on what has been happening in the last ten years, i. e., since 1578 thus finishing forty years of the Society's mission to convert Japan, in other words the mission events since Father Xavier's arrival."

In the remaining years, Fróis was able to report on events until the beginning of 1593, including a chapter on the return of four young Japanese ambassadors to Europe who visited countries such as Portugal, Spain and Italy from 1584 to 1586, during the Tensho period (1573-1591). 38

Luís Fróis' Historia de Japam is based upon the Cartas [...] de Iapão e China [...] also written by him and other Jesuits who worked at the Japan mission at the same time. Fróis even used previously printed letters, letters on Japan found in the 1575 Alcalá edition, letters on Japan published in Rome in 1579 and letters printed in Rome in 1584, as can be understood from a letter that he wrote to the Society's Father General, Claudio Acquaviva, on the 1st of January 1587. 39 However Fróis' Historia de Japam is based above all upon his own experience in Japan.

The Historia de Japam gives us a report on the development of the Jesuit Mission and historical and political events in Japan in the first forty-four years of evangelism, that is, half of the Catholic mission in Japan. Japan's contacts with Catholic countries from Southwest Europe proceeded until 1639-1640 and one can not argue that the official mission ended in 1637 with the Shimabara and Amakusa rural uprisings. Fróis' Historia de Japam is thus a narrative of the missionary work with all its hardships. One of the most interesting aspects is how Jesuits came to settle and adopt Japanese culture. While describing the 1579 events, the year in which Father Inspector Alessandro Valignano arrived in Japan for the first time, Fróis writes:

"Father Visitor decided that we needed to change all our habits such as eating and living because everything was completely different from Europe."40

I would very briefly refer to the Tratado em que se contém muito sucinta e abreviadamente algumas contradições e diferenças de costumes entre gente de Europa e esta provincia de Japão41 (Treaty containing a very brief description of some contradictions and differences of habits between Europe and this Province of Japan) which was written by Fróis in 1585 while working on Historia de Japam.

A pair of six fold Japanese screens - detail.

Attributed to KANO DOMI. Kano School. ca 1593-1600.

Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 172.80 cm x 380.0 cm.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon - Permanent loan from the Ministério das Finanças (Ministry of Finance), 1952.

"Possessions, considered exotic by the Japanese, can be seen in the foreground: a chinese folding chair, caged animals and glazed pots, probably containing Portuguese goods."

In: PINTO, Maria Helena Mendes, Biombos Namban/Namban Screens, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, p.43

A pair of six fold Japanese screens - detail.

Attributed to KANO DOMI. Kano School. ca 1593-1600.

Tempera on gold-leafed rice paper. 172.80 cm x 380.0 cm.

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga (National Museum of Ancient Art), Lisbon - Permanent loan from the Ministério das Finanças (Ministry of Finance), 1952.

"Possessions, considered exotic by the Japanese, can be seen in the foreground: a chinese folding chair, caged animals and glazed pots, probably containing Portuguese goods."

In: PINTO, Maria Helena Mendes, Biombos Namban/Namban Screens, Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 1986, p.43

Whilst Historia de Japam is an official work in which Fróis describes fervently events in many locations at the time of the Counter-Reformation, with flaming descriptions of destruction of "pagan" temples and many arguments against the Buddhist clergy, the Tratado [...] is a very personal analysis of Japan's culture and civilisation. The Tratado [...] is more literary than historical and one could add that it expresses Fróis' experience of a certain culture relativeness. The Tratado [...] is an individual supplement of one's personal experience and plays an important role in Historia de Japam as a culture history in so far as we do not know Historia de Japam's initial chapters. 42

Luís Fróis' Historia de Japam is also a narrative of historical-political events in a more crucial stage of Japanese history. The Historia de Japam covers the Ashikaga dynasty decline (1338-1573). It refers to Oda Nobunaga's rise and fall (°1534-†1582) who in a more decisive way started Japan's unification and goes as far as the most important years of Nobunaga's successor, Toyotomo Hideyoshi (°1536-†1598), who proceeded with Nobunaga's work and completed the country's unification. However in 1587 he ordered for the first time that Catholics be persecuted and under his leadership the first twenty-six martyrs were killed in 1597.

In addition to the most important historical events, the Historia de Japam offers us a variety of detailed information. Fróis refers to the number of converted people and the areas in which missionaries performed their work, as well as the Japanese and missionary's daily life. He also describes Portuguese traders' activity in Japan, civil wars and the unification of Japan.

Matsuda Kiichi, who also co-translated the Historia de Japam into Japanese, who currently knows more about Luís Fróis and his work in Japan, stresses that Historia de Japam is very important exactly due to its detailed description which cannot be found in Japanese documents. 43

The Historia de Japam is also important because many contemporary Japanese documents which most likely spoke of events in Japan referred to in Historia de Japam, were destroyed during the bloody persecution against Catholicism in the early seventeenth century in Japan.

Luís Fróis' Historia de Japam was not printed until he died. In a letter dated the 12th of November 1539 addressed to Father General Claudio Acquaviva, Fróis refers to this subject as Visitor Alessandro Valignano told him the following:

"[...] it should be shortened and condensed into a smaller book in order to comprise the most important events in one volume only a bit bigger than those printed in Rome"44

One of the reasons for Inspector Valignano not printing the Historia de Japam could lie on the fact that it featured many rhetorical passages. 45 One example of this is the description of Oda Nobunaga's rise and death:

"Not happy with the fact that he was Japan's sole ruler and accepted as such in many kingdoms, he decided to enhance his arrogance of which he was very proud. He intended to overcome Nebuchadnezzar's boldness and presumption by wishing to be worshipped not as a mortal man but as a divine and immortal man [...]."46

Fróis carries on in a more pronounced way when referring to the temple built in Azuchi under Nobunaga's orders for his deification and the people who went there:

"However Nobunaga madness and boldness were such that he wanted to be worshipped as God the Creator and the Redeemer; but God did not allow his intentions and place of worship to last more than nineteen days."47

When Fróis refers to the persecution that Christians were subject to in Japan and the political reasons behind the persecution held by Japanese daymio, the text is very often a literary document of the Counter-Reformation era. 48 It should be noted that the Historia de Japam is also useful for research and interpretation of issues related to literary analysis and literary history. 49

Of course, the Historia de Japam has shortcomings caused by the conditions and the time. The Japanese political history is not always seen sine ira et studio, but rather in a theological or even teleological perspective. Fr. João Rodrigues Tçuzzu, an interpreter, who lived the first years after Japan's reunification, wrote Historia da Igreja do Japão [...] (History of the Church in Japan [...])50 in the early seventeenth century and gave us clues on dividing Japanese history in a more general way. 51 Another improvement and development in his historical discourse are the sociological issues when describing Japanese civilisation. 52 Rodrigues lived more than ten years in Macao and knew Beijing and Guangzhou and in view of that he could detect Chinese features in Japanese culture. Prof. José Yamashiro writes that Rodrigues "[...] sees Japanese culture as submissive to the Chinese one."53 However it should be noted that Rodrigues also stresses those distinct and particular features in Japanese culture and civilisation. 54

Many data and features of Fróis' Historia de Japam are referred to or described here and there in other contemporary works. However Fróis provided us the first overall description of one of the most important periods in Japanese history as well as the history and experiences with all possibilities and hardships endured by a European (Portuguese) in Japan in the second half of the sixteenth century. In view of that, his Historia de Japam is also a valuable document when studying the 'Nanbam period' as it gives us an account of how the first European lived in Japan and their contacts with Japanese culture and its complexity.

Just before Fróis' death the first Japanese Church martyrs died on the 5th of February 1597. Fróis still had the time to write a very detailed list which was published in Italian in Rome two years later. 55

As I mentioned earlier in his letters Fróis referred to other authors, mainly Jesuit writers, and information on Japan. The Italian historian of Jesuits, in his extensive work on the activities of the Society of Jesus and the events in Japan in 1597, refers to this fact:

"A queste communi miserie una particolar se ne aggiunse, il perdere, l'un pochi mesi presso all'altro, due uomini, - l'un d'essi fu il P. Sebastiano Gonzales - l'altro fu il tante volte nominato in questa Istoria, Luigi Fróis, anch'gli Portoghese, natural di Lisbona, e similmente Professo; benemerito quanto niun'altro il sia della Cristianità Giapponese, e per le fatiche di trenta quattro anni che vi consimò, e per le memorie de'successi di quella Chiesa, che d'anno in anno scrivera in Europa, onde a lui debbo anch'io qualche parte di questa mia Opera." ("These collective miseries were burdened by another very special, that of loosing a few months after, two men - one of them being Fr. Sebastião Gonçalves - the other being the much mentioned in this History, Luís Fróis, also a Portuguese, born in Lisbon and equally ordained, meretorious more than any others of the Japanese Christianism and for the deeds which during thirty four years consummed him there, and for the memories of the successes of that Church, of which he yearly gaves news to Europe, from where I must acknowledge him credits for sections of this Work of mine."). 56

Revised version of the paper:

JORIßEN, Engelbert, Luís Fróis (1532-1597), escritor do Japão do século XV, in SIMPÓSIO DO 450° ANIVERSÁRIO DA FUNDAÇÃO E ESTABELECIMENTO DA COMPANHIADE JESUS (SYMPOSIUM ON THE 450 TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS), Lisbon, Palácio Foz, 18 April 1991 - [Oral communication...].

NOTES

1 This paper was originally presented at the SIMPÓSIO DO 450. ° ANIVERSÁRIO DA FUNDAÇÃO E ESTABELECIMENTO DA COMPANHIADE JESUS (SYMPOSIUM ON THE 450 TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE FOUNDATION AND ESTABLISHMENT OF THE SOCIETY OF JESUS).

2 "Historia de Japam" (Historia do Japão) is how it is written in the manuscript. "Luiz Frois" (Luís Fróis) is how it is written in Historia de Japam always without accents

3 See: WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., P. Luís Fróis, S. J., "Historia de Japam", 5 vols., Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa, 1976-1984, 1976, vol. 1, pp. 399-400, Appendix 3 - From where the author quotes a reproduction (copy) of this letter.

4 Ibidem., Introduction, p. 1.

5 JANEIRA, Armando Martins, Um grande Clássico por descobrir em Portugal: Luís Fróis, in JANEIRA, Armando Martins, ed., "Figuras do Silêncio. A tradição cultural portuguesa no Japão de hoje", Lisboa, 1981, pp. 243-255.

6 Idem.

See: SCHURHAMMER, Georg Otto, S. J., Leben des Verfassers P. Luis Frois, in SCHURHAMMER, Georg Otto - VORETZCH, V., trans., "Luis Frois, Die Geschichte Japans, 1549-1578", Leipzig, 1926, pp. I-IX; SCHUETTE, Josef Franz, S. J., Kurze Einfübrung in Leben und Wirken des Verfassers, P. Luis Frois, S. J., in SCHUETTE, Josef Franz, S. J., ed., "Frois. Kulturgegensätze Europa-Japan (1585), Erstmalige kritische Ausgabe des eigenhändigen portugiesischen Frois", in "Monumenta Niponica Monographs", Tokyo, Sophia Universität, (15) 1955, pp. 10-16; MATSUDA Kiichi, Ruisu Furoisu ryakuden (Luís Fróis, Short Biography), in MATSUDA Kiichi, ed., "Nanban shiryo no kenkyu" ("Studies on historical sources of Nanbam Culture"), Tokyo, Kazama shobo, 1981, pp. 129-133; WICKI, Josef, S. J., Vida do P. Luís Fróis, in WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 3-10.

Also see: JORIßEN, Engelbert, Das Japanbild im "Traktat" (1585) des Luis Frois, Münster, 1988; PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches - OKAMOTO, Yoshimoto, Segunda Parte da História de Japam, 1578-1582 (Second Part of the History of Japam, 1578-1582), Tokyo, 1938.

7 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed., Documenta Indica [...], in "Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu", 19 vols. [to follow], 1944-1988, 1948, vol. 4, p.424: - "Melchior Carneiro, S. J., Patri I. Lainez, Praep. Gen. S. J., Romam, Goa ca 20, Novembris 1559, Secunda via" ("Melchior Carneiro (from Goa) to the Father General [Diego] Lainez, (in Rome), ca 20 November 1559").

8 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed., 1944-1988, op. cit., vol. 3, pp. 153-154: "Fernão Mendes Pinto [from Sakai] to the Portuguese Fathers and Brothers (in Malacca), 5 December 1554"- Ferdinandus Mendes Pinto Nov. S. J., Sociies Lusitanis, Malaca 5 Decembris 1554 - The author in his very personal style writes: "En las tierras de de Japón, antes de llegar a Meaco, está una ciudad muy populosa, que se llama Sacai, la qual se govierna como Venecia por cónsules sin obedecer a otre. Oy dezir a nuestro Padre Maestre Francisco, que en ella estuvo, que le parecia que avia en aquella ciudad mil mercadares, y cada uno de treinta mil ducados, afuera otros muchos más ricos. Todos los moradores desta ciudad assí grandes como pequeños, hasta los pescadores, se llaman en sus casas reyes, y las mujeres reynas, y los hijos príncipes, y las hijas princesas, y todos tienen esta libertad. " ("On the land of Japan, before arriving at Meaco, there is a very populous city called Sacai governed by 'consuls' who pay no obedience to others. According to our Father, Master Francisco, who has been in this city, there apparently existed, besides others much wealthier, one thousand merchants each owing one thousand ducats. All the inhabitants of this town, both rich or poor, and even the fishermen, are called at home 'kings', and their wives 'queens' and their sons 'princes' and their daughters 'princesses', and they all find this situation normal.").

9 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. anot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 3, pp. 124-125 -"P. M. Barreto, S. J., Viceprov. Indiae, P. Ignatio de Loyola, Roman, Malaca 3 Decembris 1554" ("P. M. Barreto Vice Provincial of India (from Malacca) to Father Ignatius of Loyola (in Rome), 3 December 1554").

10 Ibidem., vol. 3, p.365; ibidem., vol. 2, p. 537.

11 Ibidem., vol. 2, p.441, 445-491.

12 LACH, Donald F., Asia in the Making of Europe, 1965-1977, Chicago - London, 1977, vol. 2, "A Century of Wonder", part. 2, pp. 138-149: The Chronicle Narrative.

13 Ibidem., p.141 ff.

14 Ibidem., p.141.

15 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, Prologue, p.5

16 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p.325 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., "Historia de Japam", part. l, chap. 43).

See: Cartas qve os Padres e Irmãos da Companhia de Jesus escreuerão dos Reynos de Iapão & China aos da mesma Companhia da India, & Europa des do anno 1549, atè o de 1580. Em Euora por Manuel de Lyra. Anno de MDXCV III, Partes III, 2 vols., Facsimile Ed. Tenri Library, 1972, Part. 1, p./fol. 131 ro [1st edition: Evora, 1598]: "Letter from Luís Fróis, 14 November 1563".

17 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 333-341 (Frois, Historia, part. 1, chap. 48) - "De como Dom Bartholomeo foi destruido e a povoaçam de Yoxoxiura queimada e assolada [...]." ("How Dom Bartolomeo was destroyed and the village of Yoxoxiura burn and pillaged [...]."); ibidem., vol. 1, pp. 353-363 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., "Historia de Japam ", part. 1, chap. 50) -"De como o Pe. Luiz Frois se foi rezidir em Tacuxima corn o Irmão João Fernandez" ("How Fr. Luís Fróis went to live with Brother João Fernandez in Tacuxima").

18 SCHURHAMMER, Georg Otto, S. J., Franz Xavier, seen Leben und seine Zai, 4 vols., Freiburg - Basel - Wien, 1973, Zweiter Band: "Asien (1541-1552)", Dritter Tellband: Japan und China (1549-1552), pp. 173-227. See: WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. anot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p.36 - Fróis writes: "Chegando o Padre (i. e. Mestre Francisco) a esta cidade, que é a metropoli de todo o Japão, achou não estar a terra da despozi[ç]ão que era necessaria para seo intento; por tudo andar alterado em guerras, o Cobosama estava fora da cidade com algu [n]s senhores principaes [...] Não fez o Padre detensa [...] e, tornando-se ao Miaco, pertendeo ver se podia vizitar ao Vo, rey universal de todo Japão, que estava recolhido em huns paços velhos, sem fausto nem estado." ("Arriving the Father [i. e. Master Francis] to this town, which is the metropolis of all Japan, he felt that the state of mind and feelings of the people were not propitious for his intents; and because of the general uproar due to war the Kubosama was out of town with some of the principal lords [...] The Father did not think twice [...] and, returning to Meaco he attempted to see if he could get an audience with the Emperor, the universal king of all Japan who lived in retirement in an old residence, without pomp or circunstance."

19 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. anot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 3, p. 130 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., "Historia de Japam", part. 2, chap. 18).

20 Idem.

21 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, (letter 41), p.282, n.21.

See: SCHUETTE, Josef, S. J., Introduction ad Historiam Societatis Jesu in Japonia, 1549-1650, edendos, ad edenda Societatis Iesu Monumenta Historica Japoniœ propylaeum [...], Romae, apud Institutum Historicum Societatis Iesu, 1968, p.471.

22 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p. 334 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., " Historia de Japam", part. l, chap. 48).

23 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p.340 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., "Historia de Japam", part. l, chap. 48).

24 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p.356 (P. Luís Frois, S. J., "Historia de Japam", part. 1, chap. 50).

25 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, p.408 (Frois, Historia, part. 1, chap. 102)- "No Miaco se ocupavão naquelle tempo os Pes. Luiz Frois e Organtino - E porque importava muito ter noticia das seitas de Japão para melhor entender suas cavilações e enganos, e mais facilmente confundir em disputa aos bonzos com o texto de sua mesma escritura, dezejavão muito os Padres poderem achar quem lhes lesse os 8 livro do Foquequio [...]." ("Fathers Luís Fróis and Organtino were at the time active in Meaco - and because in order to rethorically muddle the bonzes with the texts of their own scriptures it was extremely important to know more about the Japanese factions thus better understanding their plots and machinations, the Fathers were eagerly looking for someone willing to read them the 8 books of the Foquequio [?] [...]."

26 See: Cathalogo de los Padres e Hermanos que están en el Japón en el miez de Deziembro en el año de 1579: "El Pe Luis Frois [...]. Ha dezaseis o dezisiete años que está en el Japón, y sabe muy bien la lengoa." ("Fr. Luis Frois [...] Has been in Japan for sixteen or sevennteen years, and knows its languague quite well."), in: SCHUETTE, Josef, S. J., annot, and comm., Monumenta Historica Japoniœ I: Textus Catalogorum Japoniœ, Editionem criticam, Introductiones ad singula Documenta, Romae, apud Institutum Historicum Societatis lesu, 1975, p.109.

27 OKADA Akio, ed., Ruisu Furoisu, Nichi-O bunka hikaku (Luís Fróis, Comparação das culturas do Japão e da Europa), in "Daikokai jidai sosho" ("Contemporary Texts of the Great Sea Voyages"), Tokyo, Iwanami, 1979, vol. 9, pp. 495-636 [Japanese edition of Fróis' Treatise [...]]; MATSUDA Kiichi, op. cit., chap. Nanban shiryo no kenkyu.

28 Cartas qve os Padres e Irmãos da Companhia de Jesus [...]., op. cit., vol. 1, pp./fols. 172 ro -177 ro, pp./fols. 177 ro -181 ro, pp./fols. 82 vo -184 vo - respectively.

29 Ibidem., vol. 1, p./fol. 170 ro - For instance Fróis states the following: "Foi depois o padre cõ este velho mais duas camaras dentro, onde nos o Cubòcama estava esperando. Feita cortesia tornou, e entrei eu, e afirmo a V. R. q nunca vi casas, q fossem todas de madeira, taõ ricas ẽ tanto pera ver, porque os panos da camara, onde o Cubócama estaua erão todos cosidos em ouro, cõ hũs golfãos & passaros, que lhe davão muita graça."("And the Father crossed with this old man two further rooms beyond which the Kubosama [i. e. the shogun Ashikaga Yoshide] expected them. After due courtesies [the old man] returned and I went in, and I swear to Your Reverence that I have never seen wooden constructions as rich and astonishing, as all the draperies of the hall where the Kubosama stood were embroidered in gold with lotuses and birds of great charm."

Ibidem., vol. 1, p./fol. 180 ro - In the same letter, he goes on describing the Sanjusangendo temple in Kyoto: "[...] & logo de fronte esta hũa figura de Amidá, a quem o templo he dedicado de vulto, assentado de maneira de Bramene cõ suas orelhas furadas; rapado, de mui grande estatura, todo dourado, muito milhor do que se dourão as imagens de vulto em Frandes." ("[...] and just opposite is a figure of the Amida to whom the temple is dedicated and worshipped. He is seated on a Brahmin pose, with his years pierced, hairless and of imposing stature and fully gilt in a much better fashion that are venerated images in Flanders.").

Both theses extracts are from: - "Carta do padre Luis Frões pera o padre Francisco Pere, & mais irmãos da Cõpanhia de lesu, na China, escrita em Miàco, a 6. de Março, de 1565" ("Luís Fróis (from Meaco) to Francisco Perez and all Brothers of the Society of Jesus in China, 6 March 1565").

30 Ibidem., vol. 1, p./fol. 181 ro - "A limpeza das casas dos Bonzos, & seus jardins, & concerto, & policia em todas suas cousas, he muito pera se considerar, & por outra parte muito pera se chorar a desordem de seus costumes, & pecados." ("If the clensingness of the bonzes' residences, their gardens, their upkeep and the neatness of all their belongings is worth of praise, on the other hand is deplorable the turbidness of their customs and sins.").

31 LACH, Donald F., Asia in the Making of Europe, 1965-1977, Chicago - London, 1971, vol. 1, "The Century of the Discovery", p.321.

32 SCHUETTE, Josef Franz, S. J., Valignanos Missions-grundsätze für Japan, I Band. Von der Ernennung zum Visitator bis zum ersten Abschied von Japan (1573-1582); I. Teil: Das Problem (1573-1580); II. Teil: Die Lösung (1580-1582), in "Edizione di Storia e Letteratura" Roma, 1951-1958, 1951, vol. 1, pp. 348-352.

33 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vols. 1-5; Ruisu Furoisu, Nihoshi, translated by KIISHI, Matsuda - MOMOTA, Kawasaki Momota, 12 vols., Tokyo, Chuokoronsha, 1977-1980 [The first full Japanese translation of Luís Fróis, Historia de Japam]

34 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, Introduction, p.11.

35 Ibidem., vol. 2, p.516, Fróis writes: "Acabou-se a primeira Parte da Historia de Japam aos 30 de Dezembro do anno de 1586 [...]." ("Part One of this History of Japan was finished on the 30th of December 1586 [...].").

36 Ibidem., vol. 1, pp. 11-13.

37 Ibidem., vol. 3, Prologue, p.2.

38 Luís Fróis is also considered as the author of Tratado dos Embaixadores Iapões que forão de Iapão à Roma no Anno de 1582 (Treaty about the Japanese Ambassadors who went to Rome).

See: PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches - OKAMOTO, Yoshimoto - BÉRNARD, Henri, S. J., eds. annots., La Premiere Ambassade du Japon en Europe. 1592-1592. Première Partie. Le Traité du Père Frois (Texte Portugais), in "Monumenta Niponica Monographs", Tokyo, Sophia University, (6) 1942.

39 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, Appendix 4, pp. 400-401, n.8.

40 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. anot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 3, p.30.

41 See: Note 6.

42 SCHUETTE, Josef Franz, S. J., ed., 1955, op. cit. - For the Portuguese and German edition of the Tratado [...].

See: OKADA, Akio, op. cit. - For a Japanese translation of the Tratado [...].

Also see: MATSUDA Kiichi - JORIßEN, Engelbert, trans. and comm., Furoisu no Nihon oboegaki. Nihon to Yoroppa no fushu no chigai (The Japanese News on Fróis. Cultural differences between Japan and Europe), Tokyo, Chukoshinsho, 1983 - For a commented Japanese translation of the Tratado [...].

43 I based this on many talks with Matsuda Kiichi who also gave be other suggestions used in this work.

44 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 1, Appendix 10, pp. 406-409.

45 JORIßEN, Engelbert, op. cit., pp. 150-152.

46 WICKI, Josef, S. J., ed. annot., 1976-1984, op. cit., vol. 3, p.332.

47 Ibidem., pp. 333-334.

48 SCHURHAMMER, Georg Otto - VORETZCH, V., trans., op. cit., Einleitung, pp. XVI-XVII.

49 See: JANEIRA, Armando Martins, op. cit., pp. 243-255.

50 See: BA: JA, 49-IV-53 - TÇUZZU, João Rodrigues, S. J., Historia da Igreja do Japão, na qual, se contem, como se deu principio a pregacao do Sagrado Evangelo neste Reyno pelo B. P. Francisco Xavier hum dos prime-/yros dos, que com o gloriozo Patriarcha Santo Ignacio fundarao a Comp. a de JESV e o muito que Nosso Senhor por elle e seus filhos obrou na conversao desta gentilidade à nossa Santa Fé Catholica do anno de 1549, no qual a Ley de D's entrou em Japão, até o prezente de 1634, no dis/curso de 85 anos.? Composta pelos Religiosos da mesma Compa q do anno de 1575 athe este prezente de 1634 residem nestas partes, e pes- / soalmente se acharão quasi tudo o que em todo este tempo so- / cedeo, como testemunha de vista, e conversarão com muitos dos primeyros da mesma Comp. a q do principio forão con-/tinuando a conversão, a que o B. P. deu principio (livro [book] 1, parts 1,2; livro [book]2, part 2).

See: PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches, ed., João Rodrigues Tçuzzu, S. J. História da Igreja do Japão (1620-1633), 2 vols, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1954-1955.

Also see: COOPER, Michael Cooper, Rodrigues the Interpreter. An Early Jesuit in Japan and China, New York - Tokyo, Weatherhill, 1974.

51 PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches, ed., op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 177-190 (Tçuzzu, História, chap. 11).

Also see: E. JORIßEN, Engelbert, op. cit., pp. 234-237.

52 PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches, ed., op. cit., vol. 1, pp. 260-262(Tçuzzu, História [...], chap. 16 - "Do trajo, e vestidos dos Japões" (On the apparel and clothing of the Japanese"): for some differences between social classes.

See: JANEIRA, Armando Martins, Um Percursor da Sociologia: João Rodrigues, in JANEIRA, Armando Martins, op. cit., pp. 257-265.

53 YAMASHIRO, José, Choque Luso no Japão nos séculos XVI e XVII, São Paulo 1989, p. 54.

54 PINTO, João do Amaral Abranches, ed., op. cit., vol. 2, p.15 (Tçuzzu, História [...], chap. 3) - "A arte de Arquitectura de madeyra entre elles [...] [i. e., the Japanese] em muito perita, e primor, porque como seu modo de edifficar hé de madeyra somente [...] em geral podem competir em toda a parte na obra de madeyra, e levão grande vantagem aos Chinas com serem tão engenhozos, e primos nas artes mecanicas." ("Because their [i. e. the Japanese] methods of building deal exclusively with wood the art of wood Architecture reached great perfection and excellence [...] and their have become unsupassable in their wood craftsmanship which is much more developed than in China, also being exceedingly ingenious and meticulous in the mechanical arts.").

See: YAMASHIRO, José, op. cit., p.145 - Where the author also notes this difference.

55 Relatione della gloriosa morte di XXVI posti in croce Per commandamento del Re di Giappone, alli 5. di Febraio 1597, de quali sei furno Religiosi di S. Francesço, tre della Compagnia di Gesù, & dicesette Christiani Giapponesi. Mandata dal P. Luigi Frois, alli 15. di Marzo al R. P. Acquaviva Generale di detta Compagnia. E fatta in Italiano dal P. Gasparo Spittilli di Campli della medesima Compagnia. In Roma, Appresso Luigi Zanetti, 1599.

56 BARTOLI, Danielo, S. J., Delle Opere del Padre D. B. Della Compagnia di Gesù, Torino, Giacinto Marietti, vol. 10 "Del Giappone", Libro Primo [Book One], pp. 303-304.

* Ph. D. in Japanese and Romance Philology. Associate Lecturer at Kyoto University.

start p. 131

end p.