CHAPTER XIII MACAO

The pirate shores. — The Portuguese look of Macao. — A visit to the theatre. — Camões Grotto. — A visit to the "Barracões", the office dealing with the Chinese coolies. — The past glories and present day afflictions of the Colony. — Night arrival at the floating city in Guangzhou.

10 FEBRUARY

We escaped the normal international sea lanes to venture on the Macao route on board the American steamer Fire-Dart together with six hundred Chinese and their wives crammed as anchovies in a tin. They peacefully smoke opium and snuggle into their quilted overcoats in order to keep the cold at bay. It seems, however, that their mood is not always so subdued, and its known to have always been a risk for Europeans to ship a cargo of 'Celestials'. With the connivance of Chinese passengers, three vessels of this American company have already fallen into the hands of pirates who either massacred or, lacking courage, garroted the captain and his crew.

We take the 'Sulphur Canal' and sail between the islands of Lantao, Chung, Patung and Siko, lands of ominous memories. In effect, it was in these narrow waters that the Arratoon Apcar (eleven Europeans killed), the steamer Queen, the Wing-Sunn (near the nine islands [sic]), the Cumfa, the North Star, the Chico, and the Andreas, which closes the list for 1865, were seized and then set alight by the pirates! Horrific are the details of the fights put up by these solitary European boats against an average of thirty junks. They are made to stop by fire in a narrow pass, where they are then assaulted and boarded and all the living souls aboard are massacred except for those who have hatched the coup in advance. Afterwards, the ship's merchandise is transferred onto the assailants' boats which share among them the prey, at the end of which the ship's hull and masts are set alight, the actual evidence of their carnage finally sinking to the bottom of the sea. That is why all the sailors aboard the Fire-Dart, from the boys to the engine room recruits, have revolvers prominently displayed, while the fore and aft decks are equipped with ready-loaded cannon pointed not towards the sea but, on the contrary, positioned in such a way as they might — upon the captain's whistle — at a moment's notice horizontally sweep the vessel's entire length while — upon a prior whistle — all the crew reach safety in the topmasts. In effect, in the case of an external attack, the first to be targeted are the native passengers without whose connivance the pirates would never dare to attack a foreign vessel. In fact, an elaborate plot is required in order to take over a steamer, and I have already told you some of its catastrophic consequences. The destiny of the sailing cargoes relies more on fate. Sometimes, amidst the greatest calm, fishermen will suddenly turn into pirates, the twenty oars of each junk being set in motion they row hard and organise the assault against the unfortunate clipper powerless to escape.

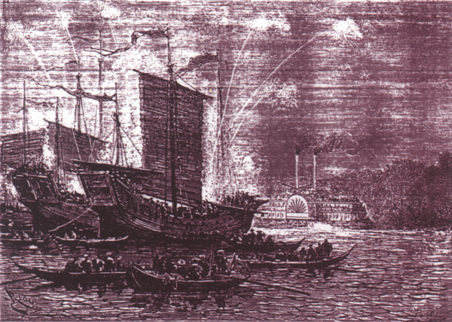

Thank God we see nothing more than the 'battlefields' which have witnessed so many incidents and that our Chinese dream at nothing besides smoking opium in their nonchalant bliss. The crispness of the air enables us to perceive the most minute sinuosities of the coves of the profusely indented archipelago which lies between Hong Kong and Macao. Suddenly, in the narrower stretches we hit upon a group of junks, each with a big eye painted at the front, superstitiously protecting their sailing course, three canons on the forecastle, three on either flank and three more on the quarter-deck, giving the skiffs of these adventurous fishermen an extremely warlike outlook. Whole families live on board. Births, marriages and deaths occur on these junks where whole families of five generations congregate in the most unimaginable jumble. Despite the flamboyant artwork, the brightly-coloured standards and the scarlet and golden stripes which decorate the elegant and sinuously daring hulls of these vessels, from what can be perceived through the steerage and quarter-deck portholes, I can find no better comparison for them than heaped baskets of rags. Perceiving the Fire-Dart, a whole population of one hundred and fifty souls emerge from the hatch (illustration. 1) of each junk and, either for sheer pleasure or merely to boast, grab hold of their tom-toms and strike them with all their might, and light firecrackers and bangers shooting them in all directions.

Illustration. 1

"Perceiving the Fire Dart, a whole population of one hundred and fifty souls emerge from the hatch [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.557.

Illustration. 1

"Perceiving the Fire Dart, a whole population of one hundred and fifty souls emerge from the hatch [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.557.

But aboard the junks not all is infantile behaviour; there is also creativity and artistic progress. Chinese are barbarians (about time we reciprocate the epithet): they only sail with the wind at their stern, travelling downstream with the monsoon, then waiting five months for the wind to change so that they can make the return trip. Each junk has a thick braided sail which is stretched flat by five transversal bamboo poles spanning the width of the sail, together constituting a cumbersome mechanism. But the rudder is a small masterpiece: it is operated by a long pole attached to a winch and is versatile enough to be sunk or lifted according to the need for thrust, which can be increased five-fold through an ingenious and peculiar contraption. The Chinese discovered that water resistance greatly increases if it directly hits a surface pierced by diamond-shaped holes rather than a flat and compact barrier. If so, the water does not simply wash against the rudder but is squeezed through these extremely narrow apertures, creating precipitous whirlpools which thus generate a much more efficacious effect.

After travelling for three and a half hours we passed the 'Typa' [sic] (Taipa) anchorage and sighted the Macao peninsula in the dying rays of the setting sun. The Portuguese colours fly high on the perched forts which occupy the dominant positions on this rocky outcrop. Imagine if you will seven or eight crazy peaks crowned by red granite crenellations, an agglomeration of deserted hillocks rising to about two hundred metres above sea level clashing with a chaos of blue, green and red-coloured residences with meridional-looking terraces instead of rooftops, a dozen cathedral bell towers, iron-barred windows, cobbled streets a couple of metres in width meandering through neighbourhoods built on 'sugar loaves' and, adjacent to all this, a circular and embracing harbour tightly sheltering thousands of junks. This is Macao!

We landed on a quay crammed with coolies and struggled up the very Portuguese 'Calçadas do Bom Jesus' [sic] (Footpath of the Holy Jesus) and 'Travessa do Santo Agostinho' [sic] (Lane of St. Augustin), true hilly corridors running between low granite houses resembling prisons. They are strange people the conquerors of this outpost! The descendants of Afonso de Albuquerque, trotting along in groups, leaning against their swords or sunk in their mufflers, are a cross-breed of Portuguese and Chinese and previous mixtures with Malays, Indians and Negroes. All in all a puny, weedy, milk chocolate, almond-eyed race vegetating in a half-Christian, half-voodoo, semi-civilised, semi-Asian environment! This place has two Anglo-American inns. After an indescribable walk through sordid alleyways, we reached one of them, a humid and stinky shelter which was more like a windowless barn elected home by cockroaches and myriapods.

This would be our temporary abode as we must obviously find a better alternative. — When we timely occupied Mexico, the United States of America was so tense about the situation that a war was imminent between us [France and the US]. Much to his regret, the Duc of Penthièvre, who was serving then with the US Federal Navy, was obliged to resign in order to avoid risking the eventuality of being compelled to fight against his own country. Eager to continue his naval career he was incorporated with the same rank into the naval forces of his cousin, the King of Portugal. After a first campaign on board the Don Juan [sic], he embarked as Lieutenant Commander of the Bartholomeo Diaz on a second lasting eighteen months to the coast of Africa, Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo and Buenos Aires. Although on leave at the time, he was nonetheless fully entitled to enjoy the privileges of a naval officer. He therefore wrote to the Governor that very same evening.

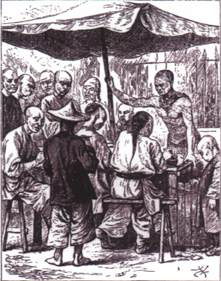

Nothing was more dismal and disgusting than our cubicle. So, in order to escape from the armies of voracious insects we asked the innkeeper for one of his coolies to take us to a Chinese theatre which are the only places worth visiting after sunset. Climbing and scaling stony walkways 'embellished' with street names I felt I would soon become as agile as a monkey! We finally entered a wooden shack where deafening music resounds. Lining it were tables, each occupied by four Chinese eating, smoking and drinking (illustration. 2). We forced our way to the mouth of the stage where a tragedy had been running, interspersed with intervals of acrobatics, since ten in the morning. We had been enjoying this curious show, with our fingers in our ears, for scarcely more than one hour when suddenly, in the midst of a big commotion, stools and tables were knocked over and the crowds were pushed right back in noisy disorder from the entrance. What could be happening? It was nothing less than the arrival of the Governor's Aides-de-camp, a Lieutenant Commander of the navy and a number of high ranking officers in full dress with plumed hats and adorned with a museum of decorations on their chests. The unexpectedness of this situation was quite astonishing. Being the sole Europeans among the audience and informally dressed in travel clothes, the trampling and jostling crowds of Chinese thought that they were coming for our arrest. But very much on the contrary, with impeccable charm, these gentlemen addressed the Prince presenting him with the Governor's greetings and invited him to stay at the palace. In order to find us they had ordered a search of the entire town on that cold and sombre night. The great multitude which by then was thronging the theatre and its immediate surroundings, which had been empty not long before, was proof that the search had indeed knocked at all doors. After exchanging a thousand pleasantries, it was agreed that we would accept the kind invitation and would be at the palace at midday the following morning.

Foreseeing that the coming formalities would prevent any further incognito excursions, we decided to make the most of the last moments of our nonofficial stay in Macao and, untiringly, took off again with our coolie towards China Town, tidily well-kept and lit with charming lanterns. Its most curious sights are the gambling houses, Macao being the Monaco of the 'Heavenly Empire'. Most of the wealthy Chinese from Hainan, Guangdong and Fujian are foolish enough to travel to Macao to lose their money playing "thirty and forty", which is forbidden where they come from. An elderly croupier with a white pigtail, a goatee of four waxed hairs, and enormously long nails, controlled this 'bank' where hundreds of gamblers flock.

Illustration. 2

"Lining it are tables, each occupied by four Chinese eating, smoking and drinking [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.560.

Illustration. 2

"Lining it are tables, each occupied by four Chinese eating, smoking and drinking [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.560.

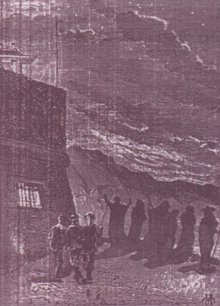

It was almost midnight and replenished by the quaint looks of the Chinese dressed in their silk outfits, each one moving about with a large 'Venetian' lantern, we asked our coolie to take us back to the cockroach den. I really do not know if the officers' uniforms had made him think that we were a gold-mine worth exploring, but the sneaky 'Celestial' seemed to enjoy misleading us. As we walked, the houses became fewer and farther between and the Prince and I eyed each other rather anxiously realizing that we were now totally disorientated and in bare, open country dotted with some ponds and clusters of bushes. Ahead of us, the road narrowed into a goats' trail while about one hundred metres behind us, six robust Chinese were following us at a hastening pace. We surrendered to reality when, suddenly, our perfidious acolyte vanished from sight, and we were left on our own at the mercy of this haunt of robbers, escaped prisoners, and Chinese good-for-nothings. And we were aware that the next few minutes could very well be all that we would have left of all those years we had looked forward to. The human shadows gradually came closer, surrounding us, becoming more defined when the pathway got darker due to its occasional overhanging boulders, and dissipated when we abruptly charged against them attempting to halt this unbearable pursuit. But they were obviously waiting for reinforcements. Their whistles remained unanswered and the assertiveness of our pace restrained them from their intentions. At last, after more than half-an-hour during which our hearts incessantly throbbed, we spotted a pale glow from the direction we instinctively thought was the European conurbation. It was coming through the bars of a skylight on a sentry-house at one of the fortified gateways along the city walls! The Prince's knowledge of military patrol codes and his perfect Portuguese quickly dissipated the hesitations of the gunner behind the crenellations, who consequently put our attackers to flight. (illustration. 3) We learned a lesson from the wise instincts of the coolie who can rejoice to have escaped at a timely interval. Had he stayed with us he would have been the first to pay for his friends evil intentions. We told Favel of our ordeal, then, exhausted, collapsed on the floor under the same blanket swearing, fortunately not too late, never to set off again so lightly!

12 FEBRUARY

Amiably toured for the first part of the day by Dom Osório, Aide-de-camp of the Governor and during the second part by His Excellency Joze Maria da Ponte e Horta, Artillery Major, we visited in just a day the whole territory, not a difficult feat considering that, if my memory serves me well, it is five kilometres long by two kilometres wide. The shape of the peninsula is exactly that of a footprint with its heel turned towards the sea and its big toe linked by a four-hundred-metre long strip of land to the large island of Xiangshan. There are nine rocky hilltops in the heel of the peninsula dominated by the forts of Bomparto, St. John and St. Jerome. The curvature of the wide insole [sic] is crammed with the piled-up housing of the Chinese who number one hundred and twenty five thousand, while the two thousand Portuguese have their residences on the opposite and outer side. Their avenue is the Praya Grande, a sea-front esplanade of manor houses with sinister bars, the 'castello' [sic] of the Governor, the harbour authority building, and the lines of villas of official and trading entities which together fully represent thecolourful, colonnaded and monastic originality of the Portuguese. Now, just imagine that a city wall runs over the ankle (our wall of yesterday night!) and that all the joints of the toes are tight and swollen. These stand-out as the scattered mountains on which are perched the forts of St. Francis, Guia, 'San Paulo do Monte' [sic] (Mount), and seven or eight more. Beyond these are the flatlands cultivated by the farmers, Mong-Ha village and the sixteenfoot-high barrier which divides the colony from the Chinese mainland.

Illustration. 3

"[...] quickly dissipated the hesitations of the gunner behind the crenellations, [who] subsequently put our attackers to flight."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.561.

Illustration. 3

"[...] quickly dissipated the hesitations of the gunner behind the crenellations, [who] subsequently put our attackers to flight."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.561.

During our interesting excursion we followed some extremely picturesque cliff roads cut into the granite hillsides. Some one hundred high-calibre cannons set on the highest points are empowered with the duty of defending the peninsula from possible sea attack, or, if necessary, in the case of riots, blasting the neighbourhood of the twenty-five thousand pigtails. We also visited the 'Plaça da Sé' [sic] (Cathedral Square), the Minster and the old municipality, headquarters of the 'Senado' (Senate) and where since 1654 the following inscription can be found:

CIDADE DO NOME DE DEOS. — NAO HA OUTRA MAIS LEAL. *

We visit the barracks, the monasteries, St. Paul's church (built in 1594 by the Jesuits and presently three-quarters burnt down), the 'Asylo dos Pobres' [sic] (Asylum of the Poors), etc., or, to cut a long story short, a number of old Christian buildings topped with crosses, embellished with saints in niches and covered with peculiar frescoes. If to this one adds the mantelet which women drape over their heads, the colossal black and oblong hats which the passing monks wear as cover, and the white cornets of the Sisters of Charity, I can guarantee you that the sensation is like that of walking through the basilicas of Lisbon or Genoa.

After the displays of modernity with which entirely new worlds have attempted to impress us during these last ten months, and the Asian regions where the industrial invasion manages to project a sensation of actuality, it feels like stepping into a dream to encounter at the borders of the Middle Kingdom this antique treasure box with Christian ruins, apparently confirming that this remote corner of the globe grew exclusively according to the patterns of our cherished monuments and the predicaments of our traditional beliefs.

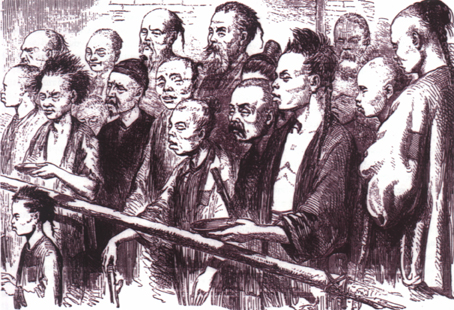

Illustration. 4

"[...] the Mong-Ha village, where stands a pagoda [sic] [...]. Bonzes do not usually welcome visitors but this site was [...] truly exceptional [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.564.

Illustration. 4

"[...] the Mong-Ha village, where stands a pagoda [sic] [...]. Bonzes do not usually welcome visitors but this site was [...] truly exceptional [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.564.

At around three o'clock, our dinghies bedecked with flags find their way past three hundred noisy junks to where the gunboat Principe Carlos is moored. Cheerful toasts are made to the future of the navy, after which we continue to follow our itinerary back on land, crossing small groves of perennial green trees which stretch right to the waterfront. The Winter sun with its faint and melancholic scarlet glow licked the horizon and hardly penetrated through the shadows of the grove as we arrived at Camões Grotto. History narrates that in 1556, the great poet survived a shipwreck in these treacherous seas by swimming to the shores of this newly-born Portuguese outpost, saving nothing more than the first few verses of The Lusiads. Ashore, he took shelter in this grotto lashed by the sea waves and, commiserating on the misfortunes of life in exile, sang the glories of his homeland. The rough and isolated location overlooks the Middle Kingdom and the immense ocean which stretches uninterrupted to the glaciers of the Southern Pole. The site, with its gigantic granite boulders, must most certainly have inspired him in writing his remarkable epic. But unfortunately the local authorities had defiled its solemn and poetical purity. Exactly where the most moving memories were to be exclusively conjured by the free flight of thought, they had built a pavilion; a construction resembling a French boulevard kiosk inscribed with verses and where a ridiculous bust in papier-mâché [sic] of the poet lay enclosed behind bars, intended as an appropriate homage to this banished man, he of the sublime and amorous soul.

Another exile, this time a Frenchman, had attempted to inscribe on one side of the grotto, in this remote corner of the earth, the memories of two misfortunes endured for the love of literature. His work is signed: "LOUIS RIENZI, religious poet. 30th March, 1827."

A pleasant gallop up hill and down dale took us to Mong-Ha village, (Illustration. 4) where stands a pagoda [sic] which looks impressive from a distance but stinks at close range. Bonzes do not usually welcome visitors but this site was truly exceptional. Due to the ancestry of Portuguese colonisation in Macao, the Chinese have become so Portuguese, or perhaps the other way around, that the bonzes name their buddhas after saints, so that in this place there can be found dozens of them named after St. Francis and St. Augustine, obese and with four arms and three heads.

The light begins to fade at the exact moment we reach the outer limits of the Colony's jurisdiction. We have reached the narrow stretch of land which connects Macao to Hangshan, which lies about two hundred metres to our front. On both sides of us crash the waves of the rising tide and the granite barrier of the Chinese Empire obliges us to halt. So, here is the famous land where the Imperial yellow flag freely flies! But what a disappointment! The 'Heavenly Land of Flowers' is nothing more than a heap of litter, filth and mess. Before us, carrying a dead man, march past a group of about sixty men dressed in white, hitting tom-toms and screaming in shrill voices. This bizarre procession, vividly reflected in the moribund purple luminosity of nightfall, further contributed to render even more upsetting the narrative of the drama enacted in this place. For exactly here was assassinated the penultimate Governor of Macao, the valorous Ferreira do Amaral, who, in claiming that Macao was fully Portuguese, inflamed the hatred of the mandarins of Guangdong, who were not prepared to relinquish their authority over the running of the affairs of the Portuguese Colony. Not daring to openly declare war, the mandarins resorted to the much less expensive solution of murder. On 22nd August, 1849, while Amaral was riding his horse beside this wall with an Aide-de-camp, he was attacked by their assassins, his bloody head and hands later being deposed at the feet of the Governor [sic] of Guangzhou.

13 FEBRUARY

As the time flew by, absorbed as we were by our long walks in these exceedingly interesting places, we started to get used to the Winter temperatures.

At the top of 'Monte' [sic] (Mount Fort), we proceeded to explore the ruins of a Jesuit monastery. From there, we decided to scrupulously investigate Macao's most characteristic site: the "Barracões", the famous entrepôts of the trade in coolies. The first human market that we visited appeared quite pleasant with flower embellished balconies, large Chinese vases and rooms furnished with mahogany furniture. These were the reception rooms... for the sole use of the staff. A small corner office with heaps of thick books was the only sign which reminded us that here 'human flesh was registered'. The walls were covered with impressive pictures (such an art loving people!) depicting the fortunate vessels selected to carry the said cargoes of 'Heavenly Sons' to the scorching, sun-drenched plantations of Cuba or the fetid guano wells of Peru. I deplore to admit that the French colours are frequently present in these sordid illustrations.

At first sight it all looked wonderful. But after the usual first exchange of pleasantries with the darkcoloured masters of the house, we noticed long corridors with compartments on both sides in which were crammed all those Chinese about 'to emigrate'. Here they lie, with their extremely drawn faces and their emaciated bodies, barely covered by their rotten rags, awaiting the hour of departure. They reveal the hideous spectacle of the most degrading of miseries prostrated in the most abominable insalubrity.

It is an extremely deplorable tale that of the coolie trade. Although begun a mere nineteen years ago, it already records the most horrendous butchery and the most infamous speculation. It is a thousand times more atrocious than the trade in Negroes which it came to replace. Blood, nothing but blood!

Provinces in the South of China are engaged in sporadic wars which so far have been impossible to extinguish. Prisoners captured by a victorious clan are sold by the conquerors to one of the Portuguese 'buyers of men' who keep travelling agents along the coast. Such is the usual system of enrolment. The numerous pirates which nest and multiply in this archipelago supply these entrepôts with most of their holdings: harmless fisherman caught defenceless. In short, through the solidarity established between them by the lure of gain, disgraceful Chinese and European entrepreneurs agree to entice, by a thousand tricks and the advancement of credit to the hordes of gamblers who flock to Macao to try their luck in the legal gambling halls, unlucky Chinese into a life of near slavery, as for every two lucky winners there are always twenty losers who spend to their very last penny and, as inveterate debtors, see no way of repaying their losses besides giving themselves to their fallacious creditors. We found this practice going on in Siam with women, children and slaves, and we have come to find it again in China for free men who pay up by relinquishing their liberty.

Illustration. 5

"Taken by force or cheated by ruse, thousands of poor devils are therefore, [...], shipped from here to remote destinations."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.569.

Illustration. 5

"Taken by force or cheated by ruse, thousands of poor devils are therefore, [...], shipped from here to remote destinations."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.569.

Taken by force or cheated by ruse, thousands of poor devils are therefore, without the slightest hindrance, shipped from here to remote destinations. (illustration. 5) Five times out often a rebellion breaks loose on board and the European crew is massacred without mercy, or, sporadically, the entire human cargo dies of suffocation trapped in the hold, the result of the cruelty of an irate captain. It is impossible to imagine anything more dramatic than these sea crossings. During four or five months, men who have been sold, treated like beasts and buried alive in a fetid hold inevitably become tremendously ferocious creatures, and when enraged by hunger and thirst and the torturous need to breathe and feel free, five or six hundred of them, blind instruments of speculation turned executioners, decide to pounce on the fifteen European sailors aboard.

Lucky are those who arrive at the final destination to spend long years in slavery. But here, their survival is much more uncertain than that of the Negroes, because while the guano merchants consider the latter their property and look after them in order to extract maximum long term profit, for them the Chinese are no more than a temporary work force to be utterly exploited during the limited period they serve, regardless of what effect this may have upon them.

My knowledge of these remote events is purely by hearsay, as it was only the report of the sinking of the good ship Martha, published in Hong Kong last January, that enabled me to start to conceive, but vaguely, the sixty or so riots which had ended in bloodshed aboard these vessels. The coolies, being apparently driven to despair as they gradually lost sight of the China coast, had to be locked in the hold while one in twenty was tied as hostage to the helms of the topgallant. During the night, due to fear of rebellion, the deck was dotted with a hundred traps armed with spikes ready to cut the naked feet of the Chinese and thus stop them from moving around. Nevertheless, they broke the hatchways, killed ten men, garroted all the others and took control of the ship. Five days later it was shipwrecked, half of the Chinese perishing at sea and only two, who were sailors, surviving to tell their horrific story.

In fact, if from 1848 to 1856 the local authorities closed their eyes to this immoral commerce, it is fair to say that more recently the Portuguese government has decided to redeem itself and keeps watch on the chaos and inhumanity which prevails before a ship's departure. After making many inquiries, here is what I can say about the present situation of the coolies before embarking — on board miseries and high sea rebellions obviously being beyond the control of Portuguese jurisdiction and unlikely to cease merely because of earlier land precautions. If an inspection of the "Barracões" proves that the coolies apparently embark these infamous vessels as free men, well the truth is that they disembark in Cuba or in the guano islands even more legally as slaves.

Each year, about five thousand Chinese leave Macao by sea for Havana and eight thousand for Callao. If this 'emigration' were to be run by disinterested and honest companies, it would admittedly be an enormous blessing for both a country which lacks basic survival supplies and another which requires a workforce. If that were the case, then these 'liberating junks' should be applauded with the greatest of joy and sympathy, granting relief from their many burdens to the most fecund people on the entire globe, the Chinese, the inhabitants of a land which is frequently unable to support all those who inhabit it. But there is no reason for the prime agents of this trade to be the clans of plunderers, pirates and twisters who thus taint this business with peculiar and indelible stains. The roots of the evil of this trade lie in the recruitment techniques. What is the point of the Chinese being asked in Macao at a later stage whether they are leaving of their own accord? Their consenting reply is devoid of meaning! Once trapped in the web of the agents cum creditors and pushed into the offices of the "Barracão" by their commissioners, who are paid forty to fifty francs a head, once bound by a signed contract drawn up by the recruiting representatives and once the mandarins of the Empire have been paid in vats of wine, the poor devils have no other option but to lie openly to the Portuguese inspectors upon being requested to make known if, yes or no, they consent to go overseas. They are clearly aware that if they refuse to go, the three concerned parties, creditors, recruiting representatives and mandarins, will relentlessly bombard them with the greatest horrors of revenge and that thus, hounded and tortured, dying of fear and hunger, they will never be able to escape their monstrous yoke and their vindictive assaults.

To summarise briefly, after the initial infamy of being trapped by a subordinate agent, the business develops in the following way. For each Chinese delivered, the agent receives a commission of fifty francs and three hundred and fifty francs for the'seller'. In accordance with this procedure, the Portuguese mulatto who showed us around his shops today received a delivery of one hundred Chinese, bought by his travelling commissioners in Guangzhou, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hunan. Thus, to put it bluntly, this fat, greasy, stocky, short, flat nosed creature with fierce eyes and a dirty beard, and looking every inch like a trader in human flesh, held, upon the expenditure of thirty thousand francs, control over a dungeon of slavery!

Before dealing (and this is the exact word for it) with the captain of a vessel, prior to dumping these living bundles of rags in the hold, the owner of a "Barracão" must first present his coolies to a Portuguese Procurador (Attorney). This is the first encounter a 'seller' has with the governmental authorities and it's here that the current legal measures start bearing fruit, and where the traffickers are punished for their wrong-doings. Whereas previously, cunning and violence would guarantee great economy and considerable profits for the representative agents, now, due to this new legality, they merely aggravate the costs with the consequent shrinking of profits. Roughly two hundred in every thousand Chinese questioned by the colonial Attorney and given the option of returning to China or sailing to Havana have the courage to refuse, thus risking revenge in the "Barracão". If the creditors who had bought, escorted and nourished them previously in their waiting sheds do not exact terrible reprisals upon them, then all the expenses invested in these so-called deserters would be lost!

Those who agree before the judges to emigrate are once again confined to the "Barracão". The new law prevents this human cargo from being shipped in less than six days, during which period of time the Attorney will once again address the coolies in the following manner: —"Make up your mind. You are still free to decide!" Frequently the waiting takes one or two months during which time they are still compelled to say the fatal 'Yes' twice before their vessel departs — all this in order to make explicit that their consent is evident.

While praising the local authorities for their solicitude and their efforts in making inquiries during the time of waiting before departure, it must be said that the longer the coolie stays in the hands of the trader the less chances he has of being freed from his sequestration. He remains a beggar, an insolvent. If he were to say: —"No, I do not want to go!", what harshness would he have to endure? Better to be sheltered and fed during two months by the entrepreneur! Caught in a vicious circle, after refusing to leave as a free man, he must acquiesce in becoming a slave to the entrepreneur in order to repay his debt.

Finally, the vessel is stowed. Soon it will set sail and the solemn hour draw close! The contract is only signed before the Attorney on the day before departure. The coolies embark and each one is sold by the proprietor of the "Barracão" to the representative of the Spanish shipping company for about seven hundred and fifty francs. After pestering with questions all our companions (i. e., the Chinese coolies), we are given as reward a copy of the muchsought-after contract. This contract is drawn up in Spanish and Chinese, and signed and initialled by the contracted Chinese, the Portuguese Attorney and the Spanish Consul in Macao, the main clauses of which are the following:

"I agree to work twelve hours-a-day during a period of eight years in the service of the owner of this contract and to relinquish all liberty during that time. — My boss promises to feed me and to pay me four piastres (twenty francs) a month, to dress me and to release me the day this contract expires."

How impressive it all looks on paper! But in reality, is not this man just becoming a planter's beast of burden for eight years? As I was informed merely the other day in Hong Kong, a fact that it seems no-one is willing to contemplate, suicide is frequently their last resort. But often they are doomed to an even more terrifying death. I can well remember the deep impression that a narrative by M. Vanéechout in the "Revue des Deux Mondes" had upon me. I shall here attempt to summarise it in a few words.

When extracting guano on Chincha island, the produce is poured through air shafts about two hundred metres long directly from the top of the rockeries into the hold of the cargo ships. The author had seen an unfortunate Chinese dragged by his load of guano through the narrow shaft, (illustration. 6) emerging at the bottom end completely pulverised. And it seems that such accidents are quite frequent there.

But, in concerning myself with the slave labour conditions of these poor souls, which I shall return to at a later point, I am forgetting to end my account of their commercial transaction.

With the exception of Guangzhou, from where, during the year of 1865-1866 alone, the Cuban agency exported two thousand, seven hundred and sixteen "miserable [...] wretches and poor devils", (illustration. 7) it is no longer all that easy to find survivors of these Chinese sold in public in the fashion of human cattle. According to the season, the needs of the plantations or surpluses of merchandise, the demand for 'Sons of Heaven' can either rise or fall in the same way as flour, coffee or cows, sometimes severely affecting the asking price for deliveries. But in general, the rate is three hundred and fifty dollars (one thousand seven hundred and fifty francs) per head. However, taking into consideration the market value of this wild mob, I seriously doubt that such a proverbial phrase as "Today, the Chinese are quiet" was ever proffered. In this way, from the Macao depot to the sugar plantations in Cuba or to the guano rockeries, the value per head of a coolie rises from three hundred francs to one thousand seven hundred and fifty, shared between those involved in the 'transaction'; that is, fifty francs for the initial contractor, four hundred francs for the "Barracão", five hundred francs for the ship's captain and five hundred francs for the selling agency upon arrival.

Illustration. 6

"[...] an unfortunate Chinese dragged [...] by his load of guano through the narrow shaft [...]."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.572.

Looking at these emaciated beings, foul smelling and in tatters, prostrated around us on the floorboards of these kennels called the "Barracões", I cannot describe the pangs of anguish which assail me. And yet, from this same terrace, Dom Osório points us out the rooftops and gardens of some Chinese who left as coolies twenty years earlier and returned as wealthy men. If these men are resistant to fever and twelve hours of slave labour per day for eight years, if they are shaped — as is said — by hard beatings and guano servitude, then they can later become rich, as salaries for workers on the free market are extremely handsome. But of the thousands smuggled and pirated in the holds of death-ridden ships, lured by the promise of riches, how many return rich? If this trade is one of the most profitable speculative operations of the nineteenth century, with each coolie agency earning some one thousand four hundred francs per head, then these 'gentlemen' will never be able to convince me that they are anything more than pirates disguised as 'salesmen'. I sense that I will always remember the sounds of the dry and horrid blows which I have heard them inflicting on the backs of men sold in lots, moved in, out and about as flocks of sheep being taken to the fields.... or to the slaughterhouse!

Illustration. 7

"[...] miserable... wretches and poor devils."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.565.

Oh, from the bottom of my heart I truly congratulate the British Colony of Hong Kong for having prohibited the emigration of coolies, either by sea or by land, in one of its very first Edicts. And this because it was felt that any sufferings which might await them in their adoptive lands should be condemned more vehemently than the hideous frauds and the disguised extortion which this trade inevitably entails in China. For Macao, the situation is a delicate one. As a leech stuck to the bottom of the Chinese colossus, this maritime settlement has never clearly determined its organic framework. Tomorrow, I hope to have the time to tell you more on this subject, inspired by the history of the Colony. Neither pure Portuguese nor pure Chinese, neither Christian nor Buddhist, caught between the deep-seated and continuous conflicts of its Portuguese Governors and the Chinese mandarins, sometimes pretending to be in harmony with European politics in the Far East and sometimes intimidated and 'kept on a leash' by the menaces of Guangzhou and Beijing, Macao only gained true status after the efforts of the brave Amaral. Unfortunately, the old slothful stains of a bastard origin are difficult to remove with a single wipe. It is obvious that if the "Barracões" were, at their very beginning, taken as nothing other than a mere cover for the 'Chinese trade', it can be presently said that what exists today is no more than the tip of the iceberg as far as the forcible 'emigration' of coolies is concerned. I sincerely hope that in the very near future the Portuguese government follows those of Ireland and Australia in discarding with the revenues from this kind of trade. Once illegal 'emigration' is purged from all profitable speculation, let the freight vessels leave by the hundred at the cost of Cuba and Callao in the same way as those from Sydney and Brisbane.

Leave it up to the thousands of Chinese who suffocate in their own land to extract themselves from their pains of misery, of hunger and pilfering. Let them and those of their kin sell themselves for eight years at one thousand, seven hundred francs a piece, but let them at least receive and keep the money themselves. Better still, allowing them to work as free men, the only ideal which can regenerate the Asian continent, could offer them a dignifying, honourable and encouraging career, their moral level raising all the more so conscious that they have freed themselves from the trade of the "Barracões", the most despicable and dirty of all I have ever known!

We had been gone from the "Barracões" a mere five minutes and were puffing as we climbed the 'Calçada da buenita Maria Virgem' [sic] (Footpath of the Blessed Holy Virgin), a rollercoaster of slippery cobbles enclosed between two rows of green houses with prison bars in place of windows, when we bumped into the travellingchair of the Portuguese government Attorney to whom a young Chinese was clinging and convulsively screaming and weeping. (illustration. 8) We saluted Sua Excelência (His Excellency) (everyone here, including myself, is addressed as His Excellency) and asked him the reason for the abundant tears of his unfortunate acolyte, who carried about his neck a wooden sign with a large number. Dom ***, in full regalia, was just on his way back from the Municipality where he had legalized the contracts of seven hundred coolies due to leave overseas shortly. But, in accordance with the law, he had invalidated the 'contract' of this miserable Chinese, because he was not yet eighteen. The boy was thus incessantly prostrating himself at the feet of the Attorney who, according to the translation we were given, he "[...] implored to let him go, because if he was to be returned to the agent who had previously sold him, he would lose all his earnings and would consequently have to endure the worst of ill-treatments." Poor boy; totally in despair because he was stopped at the very last moment from leaving for the promised Eldorado.... of guano!

14 FEBRUARY

At six o'clock in the morning we boarded the Príncipe Carlos, the charming gunboat that the Governor of Macao had placed at the disposal of the Prince, to go upstream to Guangzhou. We passed by the rocky coves of the peninsula, then gradually, the Praya Grande and the Guia Fortress, where the first lighthouse in the China seas had been built. On the horizon, we lost sight of Mount Fort, with its crenellated bastions. We said goodbye to the colony, the last European outpost we would visit before entering the 'Heavenly Empire'.

Macao was the first Colony to be founded by Western navigators on Chinese territory and exactly because this is so, its history is intimately linked to all the wars that have taken place between Europe and the great Asian power. The first Portuguese to reach the shores of Guangdong was Perestrelo in 1516. During forty years, his compatriots attempted to open modest trading factories, enticed by the never-before-dreamed-of treasures which the commercial resources of the Empire offered. But from Ningbo, in the North, to the mouth of the river leading to Guangzhou, in the south, they were successively overwhelmed and brushed aside either by hordes of natives or by the Decrees of the mandarins. Similarly they were deterred by tempests crashing their boats against the shoals of a perilous coast unable to find a single spot to safely go ashore. They were expelled from wherever they set foot despite their peaceful proclamations and their feeble naval contingents being clear proof that their only intent was to construct a commercial emporium profitable to both nations. Finally, after obtaining consent to drop anchor off the islands of Sangchuan Dao (Port.: Sanchoão) and Langbai'ao (Port.: Lampacau) in 1557, they were granted authorisation to create a factory on a deserted rocky outcrop lost at the end of an island. This they so well protected that a few years later the mandarins were impotent to chase them away, and thus Macao was founded. For more than two and a half centuries until now, this trading place has been concomitantly Portuguese and Chinese, controlled both through the rulings of the mandarins and a local Senate (Port.: Leal Senado). Curious this assemblage of two contrary powers, raising taxes in common while eyeing each other from a distance and striving to maintain political equilibrium. It is a game similar to that of accepting Macao as an exclusive commercial entrepot and the Middle Kingdom's doorway to the rest of the world. Often the European flag had to bend before the 'yellow dragon' and the local Senate, composed of twelve Juízes (Judges), three Vereadores (Council Members) and one Procurador (Attorney), all elected by the community, was obliged, in right and in reality, to comply with the mandarins, and to relent to their jealously guarded prerogatives such as jurisdiction over Portuguese citizens and the prohibition of the conversion of Chinese to Catholicism.

Illustration. 8

"[...] we bumped into the travelling chair of the 'Attorney' to which a young Chinese clinged, compulsively screaming and weeping."

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.573.

It seems that in this marriage of Catholic Colony with Asian power, the former was forced to play the passive role of oft-maltreated wife. For instance, both in 1802 and 1808, when the British forces protecting the East India Company disembarked in order to defend the outpost against an eventual attack from the French, the mandarins intervened, forcing the Portuguese to drive out their allies. Again, in 1839, when the Imperial Commissioner Lin destroyed all the Guangzhou factories and all the European traders withdrew to Macao, Lin turned out with an armed force two thousand strong, threatened the city and demanded that all British immediately return to their ships and depart, which they did, withdrawing to the moorage of Hong Kong.

The loss of sovereignty to the British of that island would represent the cost to the Chinese Empire for the end of the war. Another event was the closing of the Portuguese Customs Office in 1849, which, due to it not being reciprocated by that of the Chinese, escalated into a conflict which ended with the murder of the Governor. This crime burst with such violence the balance of conflicting currents which had so far been contained by an artificial barrier, that it provoked a new catastrophe which was to shadow all following relations. If, until then, a common gregariousness had been respected in the Chinese-Portuguese trading-post, from that point onwards, at least politically-speaking, the Colony inaugurated a new era of independence and revenge, the direct result of two hundred and ninety-two years of stranglehold, intimidation and tutelage. From 1846, Governors directly appointed by the Portuguese Crown and sworn in by an elected Senate ruled as total masters, edifying, judging and proclaiming without requiring the consent of the appointed assistants of the mandarins of Guangzhou. But the only problem with this is that Portugal has never legally become sovereign ruler of the territory of Macao, and therefore the Chinese were not entirely at fault in claiming the lion's share of administrative control. Between giving its consent in 1557 to establish a trading place and totally ceding the land, Beijing admitted there was a difference, stating that, if it had at the time closed its eyes, in reality it had not in the slightest relinquished its rights. In fact, when in 1862 delegates from the Chinese plenipotentiary squarely refused to ratify the Treaty recognizing Portugal's implicit sovereignty over the old Colony, Senhor (Mr.) Guimarães pulled a most awful grimace. Although the proposition was supported by the Chargé d'affaires of France in Beijing, the nullity of the invoked pretence was peremptorily maintained by China. Thus, by a strange twist of fate, Portugal, which opened the sea route to the Orient to other maritime nations, is now the only country to fly its flag without the approval of China, while Britain, which rules over Hong Kong, and by its side France and the United States of America, in Shanghai, do so legally, while Prussia — so it is said — is strongly tempted to gain outright possession of the magnificent island of Formosa (Taiwan).

But while the political independence of Macao has progressed slowly but steadily until reaching its summit in 1849, the commercial prosperity of the territory has charted an inverse course. During the eighteenth century, the prosperous trade of the Portuguese East India Company shook all southern China, drawing as it did its resources from where all the European imports were poured, Macao being its centre of exchange. The more Guangzhou became unbearable due to the extortion of the mandarins, the more Macao welcomed the European merchants. And not only did it attract thousands of junks loaded with merchandise but the city became a maritime resort for the tycoons controlling the Oriental trade. How many dreams were then realised in this microcosm which became the focus of the China seas, attracting to it vessels from remote regions, where they unloaded and stored the cargoes of much sought after goods from the Middle Kingdom that would later be distributed to the four corners of the globe as the diverging rays of a light source. But one day this brilliant construction collapsed. In 1841, the centre of gravity moved, thanks to the prodigious manoeuvering of Great Britain, when China gave yet another deserted outcrop, called Hong Kong, which was declared a free port, to the 'Queen of the Seas'. The birth of this British Colony extinguished the ancient Portuguese trading centre, no more than a few old hulls blackened by the reputation of their coolie trade continuing to drop anchor here.

Macao has some one hundred and twenty five thousand Chinese residents and two thousand Portuguese. In 1865, it registered two hundred and six outgoing sailings. Thirty years ago, the number was one thousand. Its commerce is reduced, to all intents and purposes, to the importing of opium, of which seven thousand five hundred containers, with an approximate value of sixteen million, three hundred thousand francs, were imported, and the exporting of tea, of which three million, four hundred thousand francs worth was exported. As the reader has most probably already guessed, in accordance with the rule of all Asian people, taxes are levied exclusively on the Chinese who either live or work in the territory, and it is from taxing them on their vices that the greatest profits are obtained. More than one hundred thousand piastres (five hundred thousand francs) come from the gambling concessions, and more than three hundred francs (?) from opium and the "Barracões"! And this is quite something in a government budget of only one million one hundred and eighty eight thousand francs. Thanks to the small dimensions of the territory and the paucity of salaries, ** general expenditure does not exceed nine hundred and thirty seven thousand francs, two hundred and fifteen thousand of which are credited in the coffers of the metropolitain state where, apparently, there is plenty of need for them.

"[...] a jolly supper [...]"

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.577.

Unique and picturesque is the physiognomy of this old trading centre which has known moments of greatness comparable to those achieved by the naval forces of Diaz, Vasco da Gama and Albuquerque! It stands for the ways of the old world and the Latin race in contrast with the impetuous management of the Anglo-Americans. Two contrasting sentries standing at the estuary of this river which flows through Guangdong from inner China! If one is prospering, it should not be forgotten that credit for the opening of China to Western trade is to be given to the other. The first sowed with much hardship, the later harvested in times of abundance.

Comparing the three Colonies of Singapore, Hong Kong and Macao, a belt of cities which the West has dotted around China, I cannot avoid thinking of the converse immigration of the Chinese, expanding, like laborious bees, in thick invading clouds around their beehives. What daring leaps they have taken. Which country of the Orient lapped by an ocean, be it the Indian, Antarctic or Pacific, has not had its beaches visited by them? We saw them in the Australian mines during the goldrush and we know that they are now frantically active in California. We have observed them as monopolistic usurers in Java, valued and cherished assistants to the 'whites' in Singapore, and as aggressive sole traders in Siam. They happily do business in Cochin-China, are honoured in Manila, make profits in the Chincha islands and work at the guano in Cuba and under the employment of other planters. What a tremendous multitude are all these people who live outside their homeland! Cherished here, hated there, on the one hand attentive, on the hand swindler, but always relentless in their business, which for them is their reason for living. The Chinese ex-patriots always return to their native country... but most frequently in a coffin. From one of the countries to which they emigrated comes the following saying: "We receive Chinese raw and alive; we send them back manufactured and dead."

For myself, who has seen so many 'Heavenly Sons' in such circumstances even before setting foot in China, who has listened to so many sincere fellows both sing their praises and denigrate them, I feel that no absolute theory can be put forward about them. If I consider a Chinaman a mere emigrant, I can only compare him to a parasitic plant, enduring good and evil according to the falling sap of the tree to which he clings, consuming it if it be stronger than he, nourishing it if it be weaker.

When he mingles with a higher race does he really desire to attain their standards? He ex-tracts for himself fecundity. The essence of his personality compels him to sink to the lowest depths in order to exploit them, to inflame vices and to nourish them with his human self.

If he should mix with a lazy, debased and indifferent people, he enlivens them with his vivacity, he regenerates them with his temperament and he stimulates them with his hard work.

Above all, when abroad, he is a formidable workman, but while close to home he is, at best, a pirate.

Translated from the French by: Isabel Doel

Originally published in French as:

BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, chap.

XIII, pp. 551-583, [this translation: pp. 551-582].

"Thousands of lanterns illuminate this nautical city".

In: BEAUVOIR, Comte [Marquis] Ludovic de, Australie (vol. 1) + Java, Siam, Canton (vol. 2), 2 vols., Paris, 1869, vol. 1, p.581.

*City of the [Holy] Name of God. There is None More Loyal.

** 18,700 francs for the Governor; 11,500 francs for a Judge; 3,960 francs for a Colonel; and 3,000 francs for an Attorney.

start p. 102

end p.