§ 1. FROM THE PLAN OF A CHRONOLOGY TO THE CHRONOLOGY OF A PLAN

The study of the evolution of the traditional Chinese sailing vessel (the 'junk') takes on particular relevance because the end of the twentieth century marks the conclusion of a phase in history for the territories of Hong Kong and Macao.

Both territories represent a specific phase in the Chinese junks' history which we can divide into four areas of different importance and duration.

1. 'Antiquity' (from prehistory to the beginning of our era),

2. Consolidation (from the first century to the beginning of the Ming dynasty),

3. Isolation (fifteenth century until 1841), and

4. The end of Chinese sailing vessels (from 1841 to the 1980's).

British presence in Hong Kong, established with the Opium Wars, soon marked the beginning of the end for the Chinese junk as a military vessel, demonstrated in 1841 by the destruction of war junks during naval combat with the British warship Nemesis.

European presence in several coastal areas of China and within the inland waterways consequently opened unleashed the gradual introduction of motorisation for traditional Chinese vessels, a phenomena already apparent at the beginning of the twentieth century. After the Second World War it accelerated and spread until the actual extinction, in the last two decades of the twentieth century, of the sailing boat as a method of propulsion.

A handful of Western observers had the privilege of witnessing the last phase of traditional Chinese vessels. They were taken in by these boats which exemplified a different approach to sailing techniques.

This was how foreign accounts, mostly published by authors like Louis Audemard (° 1865-†955), a French official posted to the Far East at the end of the nineteenth century or G. R. G. Worcester (°1890-† 1969), a customs official at the port of Shanghai at the end of the second half of the twentieth century, and other Western writers1 present in the Far East in the last hundred years, helped to preserve Chinese nautica whose decline was accelerated by the very presence of Europeans in those waters.

Macao, where the same phenomena was seen to be taking place in another way, had a longer chronological time span of around five hundred years, beginning in a period of Chinese nautical history highlighted by two facets: on the one hand a selfimposed separation from the maritime ambitions of the Ming· dynasty's Chinese administration in the fifteenth century and on the other hand, the beginning of direct nautical influences between the West and the Chinese.

§ 2. THE QUESTION OF INFLUENCES (ASIA, PORTUGAL AND HOLLAND IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY)

From a technical point of view the Western nautical world which had just reached China at the beginning of the sixteenth century, was in its infancy. However the Chinese navy, which the Portuguese had to confront in Pearl River in the second decade of the sixteenth century was the opposite, due to having inherited more than a thousand years of the evolution of local nautical techniques. This mature giant already had nothing to prove after the ostentatious journeys, at the beginning of the fifteenth century, of Admiral Zheng He· in the Indian Ocean.

Seen in this way, the arrival of the Portuguese into Chinese naval territory, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, marked the meeting of two worlds evolving in opposite ways. One helped the other, the sophisticated adult helped the young arrival in its adolescence. At the beginning of the fifteenth century, Chinese naval administration had ended up abandoning the giant junks which had marked the peak of their technical evolution. Whereas the Portuguese navy had just started to introduce a technology into Asia's waters which had evolved during the previous century with journeys around the African coast.

Under the circumstances it was not surprising that the exchange of technology which immediately followed was in a sense from the Chinese to the West, as was the case of the multiple hull and stern upper deck linings as seen in Chinese vessels during the first Portuguese mission in the waters of Canton and which were soon adopted by Portuguese boat builders.

As Sheffield and Vance noted, two historians on the medieval period in England, a thousand years prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in Asia, the exchange of technology was a one way flow from East and West. 2

In this context, Dutch marine history had discussed the inevitable Chinese influence in certain aspects of naval technology which appeared in Holland in the second half of the sixteenth century. An example being the lateral fixed lee-boards on vessels sailing around shallow, coastal waters and along the Dutch network of waterways. 3 Decades after the debate a Dutch author, A. Sleeswyk, concluded that the origin had been Chinese (this technique appears to have been first described in a Chinese manual on military techniques in the middle of the eighth century), a Dutch sailor on board a Portuguese ship, prior to 1588, being the probable conveyor of this imported piece of know how. 4 Sleeswyk analysed other details of the sails and possible influences from the East in this area, resurrecting, without being categorical, an old debate from the history of technology (diffusion versus independent local invention).

Old Canton Factories.

Mid nineteenth century. Gouache on paper. 31.0 cm x 26.0 cm.

In: Pinturas da "China Trade", [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau - Instituto de Investigação Cientifica Tropical (Arquivo Historico Ultramarino), [n. d.], ill. 44.

Old Canton Factories.

Mid nineteenth century. Gouache on paper. 31.0 cm x 26.0 cm.

In: Pinturas da "China Trade", [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau - Instituto de Investigação Cientifica Tropical (Arquivo Historico Ultramarino), [n. d.], ill. 44.

§ 3. FROM MARCO POLO TO JOSEPH NEEDHAM (1971)

As the beginning of the sixteenth century unfolded, the Renaissance in Europe undoubtedly marked a rupture. Technological knowledge which had previously flowed from Asia to Europe changed current. This is what prompted the great scholar and sinologue from the middle of the twentieth century, Joseph Needham (° 1900 -† 1995), to thoroughly investigate the subject and the answer to the question: "Why is it that modern science developed in Europe and not in China?"

However, more than any other writer, Needham was the starting point for us today in discovering the history of Chinese technology, namely in the field of nautical history. 6 He had trained in biochemistry, was a polyglot from a worldly culture and had lead a British mission for scientific co-operation in China from 1943 to 1946. He also unravelled the vast collection on the History of Chinese Technology, edited in various volumes from 1956, often in collaboration with different Chinese authors.

By beginning the publication of his immense body of work from the middle of the 1950's, Needham was able to have access not only to classical Chinese sources but also to the entire new field of historical knowledge of China which opened up with archaeology.

One of the results brought about by this was the revealing discovery in Guangdong, · at the beginning of the 1950's, of a ceramic model of a vessel from the Han· dynasty equipped with an axial rudder. 7 A major discovery breakthrough: the axial rudder appeared in Western naval history at the end of the Middle Ages thereby allowing the proportional increase of the tonnage and size of ships from then on. The presence of the axial rudder in Chinese marine technology around a thousand years before the West, gave China the technical know-how which allowed the consolidation of its navy comprising of wooden sailing vessels.

Around a century later, Chinese naval construction had reached such a stage of development that it became famous through its most outstanding inventions, namely in the field of military ships. 8 For example, ships with movable wheels alleviating the effort required to manoeuvre in lakes and rivers were already being used in the first century and were continued and developed during the Song· dynasty.

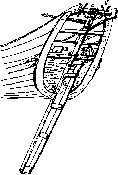

Rudder position in a junk from Fujian.

Narrow and long, extending several metres below the bottom of the keel's lowest part, this type of rudder has great hydrodynamics efficiency.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 39, fig. l, p. 95.

Rudder position in a junk from Fujian.

Narrow and long, extending several metres below the bottom of the keel's lowest part, this type of rudder has great hydrodynamics efficiency.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 39, fig. l, p. 95.

Wheel embarcation from Saigon [Cochin-China].

This model is a variant of the Guangdong type.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 10, estampa [ill.] 35, p. 551.

Wheel embarcation from Saigon [Cochin-China].

This model is a variant of the Guangdong type.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 10, estampa [ill.] 35, p. 551.

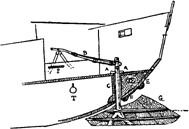

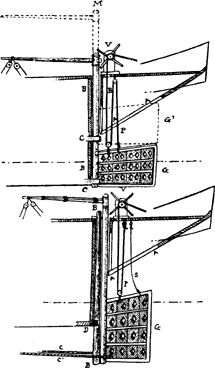

Flood gate in the Imperial Canal.

The canal links Hangzhou to Beijing and beyond passing by Tianjin and is more than 1,500 km long.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 3, estampa [ill.] 85, p. 163.

Flood gate in the Imperial Canal.

The canal links Hangzhou to Beijing and beyond passing by Tianjin and is more than 1,500 km long.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 3, estampa [ill.] 85, p. 163.

The culminating point of this technical evolution, at the beginning of the Ming· dynasty, was the maritime company headed by the eunuch Admiral Zheng He· in the first decades of the fifteenth century. It represented the greatest demonstration of the technical capacity of a society which inherited a long, deep-rooted nautical past.

Again Needham's work ended up playing an essential role in commenting on the archaeological discovery in 1962 near Nanjing · of a wooden rudder eleven metres long, a measurement from which investigators have tried to establish the original vessel's dimensions. The debate was far from being concluded even a quarter of a century after the publication in 1971 of volume IV: part 3 in the Science and Civilisation in China series, which Joseph Needham dedicated to nautical themes.

In spite of its richness, Chinese technical nautical history, as reconstructed by Needham and his collaborators, suffered from the actual time of its conception as with any account. Needham could not have foretold an essential divergence in the knowledge of ancient vessels in China, a breakthrough made in 1973 with the discovery of the wooden remains of an ancient vessel in Quanzhou· port on the Fujian· coast, a southern province of China. The archaeological investigations which followed (1974) led to the identification of the vessel as a giant trading junk from the Song dynasty whose original displacement was estimated at around three hundred and ninety tons. An abundant hoard of coins on board facilitated the precise dating of the vessel.

The wooden pieces preserved included a major part of the hull, with multiple linings and lateral divisions (bulkheads) in the interior space of the hold, one of the characteristics in Chinese construction already noted by Marco Polo9 at the end of the thirteenth century. The panelling of the stern poop, just as well preserved, allowed details of the rudder's placement to be examined. 10

§ 4. THE NOTABLE FEATURES OF QUANZHOU

For the archaeological community, the Quanzhou junk gave the opportunity to discuss details of naval construction, such as the nature of the transversal divisions of the hold (bulkheads), described as watertight panels in Marco Polo's account. Archaeological investigation revealed openings (for water circulation?) in the lower part of the bulkheads. This observation allowed to conclude later that bulkheads had, apart from an eventual use as a hull division in watertight compartments, a specific role at the moment of constructing the frame in determining the divided sections. Also perhaps it had, above all, a role in holding together the ship's structure once completed, taking into account that the transversal mid-ship framework present in ancient wooden ships built in the West were absent in Chinese naval construction then. By dividing into compartments in this way, the frame of ancient Chinese wooden vessels had a rigidity from the divided cross beamed compartments, a phenomena which Needham illustrated by comparing the junk's structure to a piece of bamboo, also divided into 'watertight' compartments.

Bust of [Admiral] Zheng He.

Maritime Museum of Macao Collection.

In: OLEIRO, Manuel Bairrão - PEIXOTO, Rui Brito, Museu Marítimo de Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, [1992], p. 58.

Bust of [Admiral] Zheng He.

Maritime Museum of Macao Collection.

In: OLEIRO, Manuel Bairrão - PEIXOTO, Rui Brito, Museu Marítimo de Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, [1992], p. 58.

But what made the discovery of this junk from the Song dynasty in Quanzhou in 1973 a vital stage in Chinese naval archaeology, were three characteristics seen in the frame:

1. The presence of a keel in the lower part of the hull,

2. Sections of the hull in "V" shape, and

3. The hull's large length in relationship to the vessel.

Up until then, with rare exceptions, most western observers had described the ancient Chinese junks as flat-bottomed vessels, whose hulls were characterised by not having a keel.

These traits, seen in numerous sea-going and river junks, were referred to as the norm in the majority of ancient texts concerning Chinese naval construction. A researcher like G. R. G. Worcester reinforced this point in his publications on the Yangzi· River from the first half of the twentieth century, reiterating the description of a junk as being a flat-bottomed vessel without a keel. The only exceptions to this so called 'rule' were the junks in Southern China, an area traditionally under strong influence from the outside world. Therefore the presence of a keel and the "V" shape in those hulls from the south can be seen as a reflection of foreign characteristics not Chinese ones. The Quanzhou · junk saw the reversal of this point of view by showing that large sailing ships from Southern China in the Song dynasty, far from having a framework which followed the 'classic' description (flat-bottomed/absence of keel) on the contrary showed opposing characteristics: deep "V" sections and the presence of a strong keel. 11

Such a discovery forced investigators to reexamine the overall concept of ancient Chinese naval construction, reinforcing the division between northern vessels and river vessels (those with flat bottoms, without 'keel') and sea-going vessels from Southern China. In this way it became clear that Worcester's analysis of vessels on the Yangzi River, though it was selective, cannot be extended to the broader vision of Chinese nautical history.

What we call today the 'keel criteria' became an essential yardstick for evaluating any type of archaeological remains of wooden hulls in ancient China. In the formal absence of a 'keel' in the classical sense of the term, in an ancient hull12 found in Penglai, · in Shandong· province in Northeastern China, a naval engineer at Wuhan · Transportation University, Professor Xi Longfei, noted that the overall pressure on the planks of the hull's bottom central section could be interpreted as a structural expression of a keel or a reinforcing of the vessel's rigidity, without the inconvenience of a overhang in the lower hull, dangerous for hull's skeletal structure's rigidity in the event of running aground. 13

The more innovative aspects revealed by the discoveries in Quanzhou in 1973 were later confirmed by several other archaeological findings. Time and time again the presence of hull sections in "V" shape and of a keel were backed up, even in the case of the discoveries located north of the China Seas, principally on the Korean coast.

This blatant reversal of previous data left researchers perplexed for some time: from the previously accepted 'hegemony' of flat hulls and no keel, came the overwhelming and indisputable shape of hulls with keel and with "V" shaped sections, from the archaeological point of view.

In reality the hull found in Quanzhou, just like others found much further to the North, was an indication of their actual presence in the past in Fujian's ancient vessels along China's network of waterways. 14 Those great naval ship builders from the Fujian · province had a dominant role throughout Chinese naval history. They were the ones who were summoned by the emperor to Nanjing in order to conceptualise the gigantic ships for the expeditions headed by Admiral Zheng He in the first half of the fifteenth century. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there are still men in Fujian who have the unchanged role of wartime naval boat builders for the Chinese Republic. 15

The upheaval caused by the Quanzhou discovery in 1973, demonstrated in its own way another episode in the geographical dichotomy of Chinese society, which is reflected even in schools of landscape painting from the Ming dynasty in the seventeenth century. 16

Apart from regional cultural idiosyncrasies manifest in such a vast territory as the Chinese empire, the north-south divide with regard to sailing vessels is above all attributable to the differences of marine oceanography, like the deeper waters of Southern China. 17 They lent themselves to a form of naval construction which would be inappropriate for travelling around in areas of numerous sand banks as in the case of the China Seas north of the mouth of the Yangzi River.

These differences between vessels from the north and south were for example demonstrated in the Kublai Khan· emperor's huge military fleet sent in against Japan in 1281. They reflected this dual polarity in their vessels' mode of construction, having part of the fleet built in Korea while the other, destined for the navy called the 'South of the Yangzi' included vessels from Fujian, the province which had been commissioned to build two hundred vessels for this naval company. 18

§ 5. ON WHAT IS PROVEN AND WHAT IS UNBELIEVABLE: THE DEBATE ON DIFFERENCES

Apart from the discussions about the shape of ancient junks, the archaeological find at Quanzhou in 1973 was an opportunity to look again and take up the other grand subject of Chinese naval history, the 'Treasury Ships' built at the beginning of the Ming dynasty in Nanjing for the voyages of admiral Zheng He, which until then had bordered between fact and fiction.

Zheng He, a favourite of the emperor, personally commanded at least six of the seven voyages to the India Ocean which took place between the years 1405 and 1433. It is interesting to analyse the circumstances whereby the subject of his voyages has appeared centre stage in Chinese naval archaeology in the last quarter of the twentieth century. The voyages of Zheng He had two quite distinct aspects from an investigative point of view. The most commented on and most obvious was the voyages themselves -- prestigious ventures which served an unusual naval, military and diplomatic purpose.

The pomp of Zheng He's trips left the question of the vessels, built specifically for the great naval company which authorised these voyages, in the shadows for a long time. Ancient accounts from the Ming dynasty cite the number and measurements of the vessels and with the passage of time and the repetition of references, each time more remote, each time less bona fide, references from ancient documents to Zheng He's voyages in numerical terms have lost their significance. The sudden prominence given to the subject in volume IV: part 3 of Needham's work, published in 1971, saw a change in the kind of interest given to old sources. In commenting on the discovery in Nanjing in 1962 of a large wooden rudder, and in putting forward propositions for calculating the original vessel's size equipped with such a rudder, Needham launched the debate which reached its culmination in 1996. 19

HUA PIGU 花屁股 FOOCHOW POLE JUNKS

mostly transport lumber & are believed to have remained unchanged for 500 years. They maybe up to 180 feet long.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China / Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, I11. 25.

HUA PIGU 花屁股 FOOCHOW POLE JUNKS

mostly transport lumber & are believed to have remained unchanged for 500 years. They maybe up to 180 feet long.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China / Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, I11. 25.

This debate revolved around the two parameters taken from ancient Chinese sources:

1. The size of Zheng He's larger trade vessels, and

2. The proportions of width to length.

The question of size refers to the translation to metric of the measurements given in ancient texts. According to them, the treasury' ships, the larger ships of Zheng He's fleet, were forty four zhang · in length and eighteen in width which made the vessels around one hundred and thirty seven metres in length and fifty metres wide. Regarding the eventuality of error in transcriptions of arithmetic found in ancient sources, Ann Vong, a researcher from the Museu Marítimo (Maritime Museum) in Macao, reminded us that the numbers in question appeared in ancient texts not only in numbers but in a literal transcription in full. This diminished the hypothesis of error in the values of 'forty four' and 'erighteen' which were given for the vessels' length and width explicitly in zheng. 20 In spite of this, both measurements were considered 'unrealistic' by a certain number of researchers.

The reason for this 'impossibility' had to do with the limits reached in the West in naval construction for wooden vessels at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century. The numerous vessels of great size built in this final period of wooden sailing ships lead boat builders in the West to admit that it would be difficult to have a completely wooden boat over seventy five metres in length without sacrificing its sturdiness at sea.

According to André Sleeswyk, the Dutch researcher who has immersed himself in these questions, the seventy five metre limit for a wooden vessel could be extended to one hundred metres in the case of a 'composite' vessel built of wood with metal reinforcements. 21 In both cases, vessels of forty four zhang from the fifteenth century surpass the permitted 'limit' by a long way, leading the majority of commentators into disbelief in relation to the texts which they sought to analyse in an attempt to reinterpret them. 22

One of the aspects of this reinterpretation had to do with the liao, · a unit quoted in ancient texts to indicate the weight of cargo but which recent naval historiograpy has been reanalysing under the concept of a measurement for volume23 in an attempt to reconcile the bare facts with a more 'plausible' length and size for Zheng He's ships. Several researchers have put forward a hypothesis on this subject, the last being André Sleeswyk's calculation. 24

The rebelo.

A boat used for the transportation of port vine in the Douro River, Northern Portugal.

In: WOHL, Alice - WOHL, Helmut, Portugal, New York, Scala, 1983, p. 117.

The rebelo.

A boat used for the transportation of port vine in the Douro River, Northern Portugal.

In: WOHL, Alice - WOHL, Helmut, Portugal, New York, Scala, 1983, p. 117.

Chinese naval archaeology has come to reanalyse the questions of Zheng He's vessels following the discovery of the Quanzhou junk, not only because of its precise dimensions but also because of its proportions, considered until then as unrealistic, between the ship's length and width, a ratio with a value of around two-fifths in this case. That corresponded to the ratio quoted for the treasury ships in ancient sources at the beginning of the fifteenth century (forty four/eighteenths). Among others, this aspect of the Quanzhou junk found in 1973, as professor Xi Longfei, a naval engineer at Wuhan Transportation University admitted, provoked the reappraisal of written history and of Chinese archaeology. The find at Quanzhou was an opportunity for Western researchers, namely the underwater archaeologist from Perth, Jeremy Green, to add to the debate on the Chinese naval archaeological concepts used since 1960's to study the remains of western marine vessels. These were specifically the notions of 'first hull' or 'first skeleton', notions that were opposed to the oldest traditions ('first hull'), evident since protohistory until the twentieth century in some areas of the world, like Scandinavia, the Douro River and in the Far East, to the 'modern' tradition as seen for the first time in a vessel from the seventh century in the Mediterranean25 and which continued until our time as 'first skeleton'.

In the first instance, with 'first hull' the planks which make the hull were built without the aid of a prior transversal structure as long as this constituted the first stage in construction. 'First skeleton' in which the planking of the hull was reduced to an outer 'skin covering' whose function was limited to making the entire hull's watertight compartments solid with a dense network of crossbeams and long supports. However a 'first hull' was when the initial plank determined the hull's capacity and the shape of the vessel and constituted in itself, by virtue of its own resilience and the way the pieces were joined together, a part of the initial structure - strengthening of the whole vessel. An obvious example of 'first hull' was the 'rabelo' ('plough-tailed') vessel from the Douro river. 26

Junks Paysing an Inclined Plane on the Imperial Canal -- detail.

T. ALLOM.

Ca1843. Engraving by W. Floyd. Hand coloured. 19.0 cm x 12.5 cm.

In: Os Cursos da Memória, [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado, 1994, ill. 62

Junks Paysing an Inclined Plane on the Imperial Canal -- detail.

T. ALLOM.

Ca1843. Engraving by W. Floyd. Hand coloured. 19.0 cm x 12.5 cm.

In: Os Cursos da Memória, [Exhibition Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado, 1994, ill. 62

Such concepts allowed the more precise evaluation of the essential difference that separated the traditional Chinese hull from the classical building techniques used in Western naval construction recently. The same concepts showed why and for what reason the criteria established in the nineteenth century in the West for wooden marine construction of large sized vessels did not apply to Chinese construction techniques from the fifteenth century for example. The considerable gap which had separated the underlying concepts of traditional Chinese naval construction ('first hull') from those which regulated the building of the latest clippers and other large wooden vessels made the recent considerations of Western investigations on the 'possibility' or 'impossibility' of building boats over one hundred metres or more in China at the beginning of the fifteenth century invalid. Abundant examples in Chinese technical history, from the past and present, of works considered 'unrealistic' or 'impossible' by Western engineering standards were however successfully realised by Chinese engineers. The great road and rail bridge at Nanjing over the Yangzi River is perhaps the most recent example of these differences of approach to engineering feats which go beyond the theoretical models or practical examples in existence. The bamboo scaffolding still used still in Chinese civil engineering, even for buildings of several dozen floors, reveals up until which point such differences in techniques can be applied to works of considerable scale.

§ 6. THE FATHER OF ALL SHIPS

Along the same lines, the question of the Chinese junk's origins forces the thorough reappraisal today of research from the past. After the exemplary work of G. R. G. Worcester in the first half on this century in collecting the shapes of traditional vessels in the Yellow River basin, in pondering over the question of the origins of the junk, he concluded that it was probably to do with the expansion and development of the primitive raft, 27 which made the junk emerge as the predecessor of a three dimensional configuration whereby the vessel's shape would be build out of a bamboo trunk, rounded off and smoothed, without a keel but reinforced on the inside with lateral divisions.

Such a view is based on Worcester's observations: there does not exist, or appear to exist in the entire field of Chinese nautical history, a monxyle canoe, the rustic vessel hulled out of a single trunk, which constituted in some way the 'soul' of all later wooden built vessels.

In taking the works of Worcester as a basis, Needham inherited this view of the Chinese nautical world which was then destroyed by archaeological discoveries after the war. Previous investigations in Korea and Japan28 had already produced evidence of the presence of a monoxyle canoe in the nautical history of the Far East, whereby making the total absence of such a vessel in Chinese nautical history's past appear as an aspect yet to be clarified. The work of the archaeologist Dai Kaiyuan29 and others have allowed the discoveries carried out by Chinese archaeologists in the second half of this century to be brought to the fore. The consequences of such discoveries were henceforth analysed by researchers who were challenging the previous historic model proposed by Worcester and expounded in Needham's writings.

A junk travelling along a canal near Canton -- detail.

AUGUSTE BORGET.

Originally printed in: [BORGET, Auguste]. Sketches of China and the Chinese, Paris, Publié par Goupil et Vibert Editeurs. 1842.

In: HUTCHEON, Robin, Souvenirs of Auguste Borget, [Hong Kong], South China Morning Post, 1979. p. [87], top illustration.

A junk travelling along a canal near Canton -- detail.

AUGUSTE BORGET.

Originally printed in: [BORGET, Auguste]. Sketches of China and the Chinese, Paris, Publié par Goupil et Vibert Editeurs. 1842.

In: HUTCHEON, Robin, Souvenirs of Auguste Borget, [Hong Kong], South China Morning Post, 1979. p. [87], top illustration.

§ 7. THE END OF SAILING JUNKS (CHINA, HONG KONG, MACAO)

Of all the moments of the Chinese sailing vessels' history, the most enigmatic and curious was the final stage. Apart from the difficulty in placing the precise moment when the junk disappeared as a maritime sailing vessel in China, we can say, as an initial approximation, that sailing junks were still around in Southern China in the first years of the 1980's, having disappeared since then. 30 In some areas where dock workers were exposed to industrialisation, as in Hong Kong, the phenomena seems to have occurred earlier. 31 In other regions they duly carried on. 32 The situation differed little in the areas of great river navigation, like on the Yangzi River. In the higher regions of the Yangzi, around the city of Chongqing in Sichuan province, where one can still see some traditional wooden vessels, in spite of none being powered by sails, an engineer from a local shipping company estimated that sailing vessels had disappeared in the middle of the 1970's. 33 In the Jialing River, a tributary which opens into the Yangzi River at Chongqing, · the skipper of a converted ferry boat, recently questioned as he travelled down the river from the city of Hechuan, added that the last sailing vessels had been seen in that river eight years earlier, meaning around 1988-1989. 34 In some cases, as in the port of Qingdao, in Shandong province, in the North East of the China Seas, ancient traditional wooden designs, with a complicated system of an immobile rudder inherited from a long tradition, still existed in the boats used by local companies transporting salt. In this instance the vessels were built forty years ago and first operated as sailing boats before being motorised later on. 35

Even in a metropolis the size of Wuhan, in the middle of the Yangzi, one could still see the traditional designs in recent vessels, motorised or not. 36 According to the retired naval engineer, Li Bang Yan, the moment of this important change from sails to motors for Chinese traditional maritime vessels was found around the years 1956-1966. 37 According to this naval expert, one could see large junks like the big five-masted junks (Sha-Chuan) · until much later along the coasts of Jiangsu · province, north of the mouth of the Yangzi.

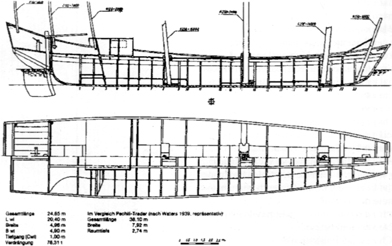

Within this very context, a vital chapter, almost unknown outside China today, took place in the recent history of the Peoples' Republic of China regarding the history of local traditional vessels. During this time38 the Chinese government took the initiative to finance a vast programme for making an inventory of the traditional vessels in China both at sea and on the lakes and rivers. This inventory, carried out by naval engineers and their respective assistants, allowed the resurveying of around three hundred and fifty different types of ocean going vessels and around ninety types of vessels on the Yangzi River. Some of the designs collected on this subject were reproduced in a 'catalogue' published in an edition of several hundred, with the collaboration of numerous naval engineers. This catalogue included twenty eight types of vessel from the Yangzi surveyed in the course of the programme. Among this rare reflection on the past through this enormous undertaking of such an inventory appeared plans published in Germany of a sailing-fishing boat on Taihua · (Tai Lake) east of Shanghai. ·39

A junk from Bei Zhili in full sail.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 47, fig. 1, p. 108.

A junk from Bei Zhili in full sail.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 47, fig. 1, p. 108.

Catamaran.

Special raft used in Western China for fishing in rivers and along the sea coast.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 79, p. 504.

Catamaran.

Special raft used in Western China for fishing in rivers and along the sea coast.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 9, estampa [ill.] 79, p. 504.

It is within this context that Needham's work on the most remote aspect of Chinas nautical history appeared. It is also thanks to the appearance in the middle of the 1970s of scientific equipment and criteria which prompted the unleashing of powerful ripples in Chinese naval archeology because of the junk from the thirteenth century discovered in Quanzhou.

Recent developments in the debate at the heart of this subject were not to displease Needham's search for an answer to the question on the entry or non-entry of China into the scientific world: In André Sleeswyk's most recent article on this question surrounding the dimensions of Zheng He's giant fleet from the fifteenth century, he referred to the 'customary astuteness' of Chinese naval architects in treating a measurement of weight like the liao as a measurement of volume, which, in the hypothesis presented by the Dutch naval archaeologist, presupposed the use of such complex formulae as the square root from the principal dimensions of a vessel or even the fractional powers. 40 Such questions were, before anything else, related to the giant vessels in relationship to the sizes usually built at shipyards. One of the more potentially valuable ideas evolved by Sleeswyk in his article was that all the mathematical workings underlying the complex question of dimensions of the treasury ships would not have been more than the tools destined to allow Chinese naval architects, from the beginning of the fifteenth century, to launch into naval engineering on a scale hitherto unknown, a scale like that which was demanded by the scale of the actual Imperial Nautical Company headed by Admiral Zheng He.

The impossibility of proving and experimenting with the huge vessels in question, the mathematical findings suggested in Sleeswyk's theory would permit the exploration by calculation and mental effort, of a technical world which man had not yet penetrated.

Could this have been the step China had made before the beginning of the fifteenth century towards modern science?

YA PIGU 鴨屁股

"Lorcha" is a hybrid craft with fast Western hull & and convenient Chinese sails. First built in Portuguese settlements in China early in 16-th century, they were engaged, besides commerce, in suppression o piracy due to their speed.

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China / Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990. I11. 33.

Ha Kau Tor is a deep sea trawler fishing in pairs in Hong Kong - Swatow waters.

[...]This junk is about 60 feet long, 18 feet wide buy some are up to 80 feet in length. Backstays & shape of hull reveal western influence

In: SOKOLOFF, Valentin A., Navios Da China / Ships of China, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, I11. 29.

Such an hypothesis would have certainly caused Needham to be enthusiastic but we know that the Chinese administration of the fifteenth century decided to close the door to the West and restrain once and for all the entire maritime ventures undertaken in the previous decades. Less than a century after the death of Zheng He the first Portuguese ambassador arrived in Guangzhou. A cycle was closed, another had just opened. With the inversion of technical developments which were the opposite, the junk, a symbol of Chinese navigation, disappeared unnoticed.

The coming together of two nautical worlds gave birth, apart from the first influences immediately apparent in Portuguese naval construction from the sixteenth century, later had influences the other way around, as in the case of the 'long chuen', which demonstrated the Western traits adopted by Chinese nautics. The interchange became more widespread in the nineteenth century. 41

Some privileged witnesses followed the last stages of Chinese vessels outside the territory of the Peoples' Republic. An old employee of the Macao Port Authorities, 42 in local service since 1955, was able to accompany this final stage, having throughout his long career until the beginning of the 1970's, carried out several inspections in the course of the building of vessels and assisted in the dismantling of about two hundred others.

In the course of such an experience, this privileged witness was able to see some subtle developments in the configuration of vessels and in the material used, 43 emphasising the importance of the choice of the very materials and even the vessels' configuration, the costing and the needs of the owner and future ship owner. From his accounts the concept of extreme flexibility in the construction of Chinese vessels emerges for the same type and in the same period.

Plan of a fishing vessel from Tai Lake.

In: BROELMANN, Jobst, Die 'Sieben-Fächer-Dschunke' und Andere Boote des Taihu-Sees in Südchina, in "Das Logbuch", 1 (30)1994, pp. 17-26.

Far from dying off with the end of wind power, the history of the Chinese junk was prolonged in the most modern vessels, 44 even when their appearance suggested a form of construction directly inspired from the West, as in the case of fishing boats actually built on the Island of Coloane, in Macao (Summer of 1996). A close inspection revealed that in reality such vessels followed the most ancient principles of Chinese construction like those mentioned earlier, the planking of the hull installed almost without the help of an internal transversal structure, a fact noted by the naval ethnographer Rui Peixoto and Manuel Bairrão Oleiro in a work dedicated to the collections in the Museu Marítimo (Maritime Museum) of Macao. They observed the little importance of a structural skeleton in fishing boats built in Macao, 45 a clear 'symptom' that we were in the presence, not of the principle in force in western construction ('first skeleton'), but of 'first hull', representative, in this case, of the most ancient of Chinese traditions.

Or in other words: five hundred years after the arrival of the Portuguese navigators in the waters of the China Seas, the history of vessels in the region, in spite of the violent transformations suffered, such as the 'restraining' of nautical activity in the Ming dynasty and the recent motorisation of vessels, is far from coming to an end. 46 In Tai Lake, west of Shanghai, some great examples of wooden, traditional sailing boats still survive. But the majority of working vessels, all with sails and motors, are henceforth made up of various elements, wooden cabins and ferro-cement hulls, with variations like steel plated decks. The cemeteries of vessels on the same lake teach us today something that no history book has recorded to date: the slow death of the authentic prototypes built by fishermen in an attempt to adapt to changes in availability for boat building materials. We see their huge wooden hulls, lined with cement, agonising beneath a grey April sky, failed attempts one after the other that hardly lasted in which the wooden part became less and less. Today, floating in front of the abandoned prototypes, we can see the finished versions of these first attempts, fishing boats with sails in ferro-cement, their shape following closely, yet with subtle differences, the shape of their ancestors' wooden vessels. With the beginning of Summer 1996, huge sailing boats will return to billow their sails to the sky of central China, the last sign of a nautics which even today, in their most modern forms, hydrofoils or flat-topped ultramotorised vessels, and some vessels with sails, some built of wood, all revealing a greater exuberance of shapes and techniques that ever was, the stamp of Chinese boat builders.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Linda Pearce

A junk off the coast of China.

AUGUSTE BORGET.

Inscribed: 10 avril [april] 1838. Pencil on paper.

In: HUTCHEON, Robin, Souvenirs of Auguste Borget, [Hong Kong], South China Morning Post, 1979. p. [5], bottom illustration.

Rudder position in a Kua Zi junk from the Upper Yangzi River --

diagramatic section.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 40 - right, p. 97.

TOP: Junk from Hong Kong.

BOTTOM: Junk from Hainan.

Rudder position in junks from Guangdong -- diagramatic section.

LOUIS AUDEMARD.

In: AUDEMARD, Louis, Juncos Chineses, Macau, Museu Marítimo de Macau, 1994, part. 2, estampa [ill.] 38 - left (TOP) + right (BOTTOM), p. 94.

NOTES

1 DONNELLY, Ivon Arthur, Foochow Pole Junks, in "Mariner's Mirror", 9 (8) 1923, pp. 226-231; River Craft of the Yangszekiang, in "Mariner's Mirror" 10 (1) 1924, pp. 4-16; The 'Oculus' in Chinese craft, in "Mariner's Mirror", 12 (30) 1926, p.339; Chinese Junks and Other Native Crafts, Singapore, Graham Brash, 1988, p.142 [1st edition: 1924]; DONNELLY, Ivon Arthur, intro., Chinese Junk Models, Shanghai, [n.d. -- terminus a quo 1922; probably edited in 1930]; TING, V. K., DONNELY, Ivon Arthur, annot., Things produced by the Works of Nature: Published in" 1639, in "Mariner's Mirror", 11 (3) 1925, pp. 245-250. WATERS, D. W., The Chinese Yuloh, "Mariner's Mirror", 32 (3) 1946, p. 189; The Straight, and Other Chinese Yulohs, in "Mariner's Mirror", 41 (1) 1955, pp. 60-61. CARMONA, Arthur L. Barbosa, Lorchas, Juncos e Outros Barcos Usados no Sul da China, Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1954, p. 73.

2 SCHOFIELD, John - VINCE, Alan, Medieval Towns, London, Leicester University Press, 1994, p.210 -- "During the entire period 500-1500 the Near East was superior to the West; technologically the West had little to bring to the East, and technological movement was composed of European cities and ports [...]. Discoveries which came by this route included the tidal mill, water clock, segmental arches in buildings, reservoirs and dams, gunpowder and cannons, the magnetic compass, alcohol, sulphuric and hydrochloric acids, asphalt, soap, tin, glazed and lustre-painted pottery, the spinning wheel, paper (including the airmail variety, which was developed so it could be carried by pigeons), many secrets of the tanning industry via Cordova in Spain, sugar, and coffee (al-Hassan and Hill, 1986)." The source quoted by these authors is: AL-HASSAN, A. Y. - HILL, D. R., Islamic Technology: An Illustrated History, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

3 GREENHILL, Basil, Distribution of Leeboards, in "Mariner's Mirror", 55 (1) 1969, p.16; DORAN Jr., Edwin, The Origin of Leeboards, in "Mariner's Mirror", 54 (4) 1968; PRINS, A. J. H., Dutch Maritime Inventiveness and the Chinese Leeboard, in "Mariner's Mirror", 56 (3) 1970, pp. 349-353; HOGBEN, F. B., Dutch Maritime Inventiveness and the Chinese Leeboard, in "Mariner's Mirror", 57 (1) 1971, p. 24.

4 SLEESWYK, André Wegener, Some Hidden Problems of Chinese Nautical Technology, in JOHNSON, W., ed. "Shaky Ships: The Formal Richness of Chinese Shipbuilding", Antwerp, Nationaal Scheepvaartmusuem, 1993, pp. 29-30 -- "The Lee-board and the Fore-runner of the Gaff rig."

5 GOLDSMITH, Maurice, Joseph Needham: 20th Century Renaissance Man, Paris, UNESCO, 1995, pp. 71, 86, 106, 114.

6 NEEDHAM, Joseph, WANG Ling - LU Gwei-Djen, colls., Civil Engineering and Nautics, in "Science and Civilisation in China", 5 vols. [cont.], Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1956-1997, 1971, vol. IV, part. 3; NEEDHAM, Joseph, Introductory Orientations, in "Science and Civilisation in China", 5 vols. [cont.], Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1956-1997, 1956, vol. I, p. 6 -- Of the documentation at his disposal, apart from Western and Japanese material, Needham spoke of the "[...] veritable ocean of the extant original Chinese books themselves [...]."; apud GOLDSMITH, Maurice, op. cit., p. 108.

7 A copy of this model is found today on exhibition in the Regional Museum of Guangzhou, situated in the Zhenhai tower, in the northern sector of the city.

8 Texts from the eighth century mentioning ships with two wheels operating like feet "[..] and which made the vessel move forward as quickly as a horse at a gallop." Texts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries speak of ships with four-and-a-half and up to thirteen wheels (for the sinologue Jacques Dars, the odd number of wheels could have corresponded to boats equipped with a wheel at the prow).

See: DARS, Jacques, Les Bateaux á Roues (Chechuan Chelunchuan, Chelunge), in "La Marine Chinoise du Xe. au XVIe. Siècles", Paris. 1992, pp. 109-112.

9 The authenticity of Marco Polo's accounts has been recently debated and the hypothesis has been put forward by that he did not even visit the Chinese continent at the end of the thirteenth century (WOOD, Frances, Did Marco Polo Go To China?, London, Secker and Warburg, 1995), but it is sufficient to quote here his account on Chinese vessels from the period, a precise and pioneering account, to authenticate this part of the Italian explorer's voyage.

10 GREEN, Jeremy, The Song Dynasty Shipwreck at Quanzhou, Fujian Province, People's Republic of China, in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 12 (3) 1983, pp. 253-262 -- notably, from an abundant bibliography which exists on this vessel. The 'Quanzhou junk' is able to be seen in an annex of the Kaiyuan temple, in the old part of Quanzhou.

11 GREEN Jeremy, Eastern Shipbuilding Traditions: A Review of the Evidence, in "Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology", 12 (2) 1986, p. 1 -- "420 x 270 mm".

12 XI Longfei - XIN Yua Nou, Preliminary Research on the Historical Period and Restoration Design of the Ancient Ship Unearthed in Penglai, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE -- [Proceedings of...], Shanghai, Society of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, 1991--The authors date it to the end of the Yuan dynasty or beginning of the Ming, i. e., "[...] around 1274-1376 in our period, not later than 1376."

13 XI Longfei, Wuhan Transportation University, 28th of March 1996 -- oral communication.

See: XI Longfei - XIN Yua Nou, op. cit., p. 236 -- For a reproduction of a cross-section of the central piece of the hull found in Penglai. The sections of the bulkheads numbered 3 and 5, given as illustrations 2 and 3 in this work (p. 235), show how the "keel", quoted as such by the authors (p. 225), presents a slight or no overhang in the lower part -- flat -- of the hull.

14 CHEN Yan Hang, Quanzhou Museum of Overseas Communication History, Quanzhou, 13th of April 1996 -- oral communication.

15 SWANSON, Bruce, Eight Voyage of the Dragon:: A History of China's Quest For Seapower, Annapolis/Maryland, United States Naval Institute, 1982, appendage H -- For the role of the Fujian officials in the last hundred years in China's history of its wartime navy. The list of Chinese wartime marine officers in 1888, giving the province they were from showed that 60% of those in service at the time came from the Fujian province.

16 The name most associated with this theory is that of the painter, calligrapher and scholar, Dong Qi Chang · (° 1559 - † 1636).

See: SULLIVAN, Michael, A Arte Chinesa e Japonesa, [n. n.], Grolier, 1969, p.86 [2nd edition: 1975] --"[...] according to whom, all scholarly painters of landscapes in monochromatic paint, a free style based on Ding Yuan and the masters of the Yuan dynasty, belonged to a 'Southern' tradition: professionals, painters and decorators and members of the Zhe School were relegated disdainfully to the 'Northern' School. The theory gained broad acceptance among men of letters because it suited their own ideas and preconceptions [...]."

17 NEEDHAM, Joseph, WANG Ling - LU Gwei-Djen, colls., op. cit. -- "Quoting from a translation of Daily Additions to Knowledge (Jih Chih Lu) · a manuscript from 1673:

"The sea-going vessels of Chiang-nan [ ] · are named "sandships" for as their bottoms are flat and broad they can sail over shoals and moor near sand banks... But the sea-going vessels of Fukien [ ] · and Kuangtung [ ] · have round bottoms and high decks. At the base of their hulls there are large beams of wood in three sections called "dragon-spines". If (these) ships should encounter shallow sandy (water) the dragon-spine may get stuck in the sand, and if the wind and the tide are not favourable there may be a danger in pulling it out. But in sailing to the South Seas (Nan-Yang) [ ] · where there are many Islands and rocks in the water, ships with dragon-spines can turn more easily to avoid them."

The description should be read to indicate a keel scarfed together in three parts [...]."; apud GREEN, Jeremy, 1986, op. cit., p. 4.

18 During the preparations, the superintendent of maritime trade in Fujian, Pu Shou Geng, complained of the excessive number of vessels requested from his region. At that stage fifty vessels had been finished.

See: WALSH, Paul V., Invasion Attempt Repeated, in "Military History", Leesburg, Oct. 1993, pp. 60-69 -- In this work about about the two invasion attempts by Kublai Khan's fleets, from 1274 to 1282, the author considers the difficulties which followed them throughout the voyage (rotten wood in the ships) as a reflection of faulty construction.

19 SLEESWYK, André Wegener, The 'Liao' and the Displacement of Ships in the Ming Navy, in "Mariner's Mirror", 82(1) Feb. 1996, pp. 3-13 -- This article, far from putting forward a final answer, marks a new stage in the discussion. Sleeswyk is author of several works on the questions of engineering and naval archeology related to the largest wooden vessels in history.

20 (VONG, Ana, Maritime Museum, Macao -- 15th of March 1996 -- oral communication).

21 SLEESWYK, André Wegener - MEIJER, Fik, Launching Philopator's 'Forty', in "International Journal of Nautical Archaeology", 23 (2) 1994, pp. 115-118. Also see: SLEESWYK, André Wegener, Some Hidden Problems of Chinese Nautical Technology, in "Large Wooden Ships in the West and in China", pp. 26- 29 -- Where the author develops this same subject.

22 MILLS, J. V. G., trans. and notes, Ma Huan Ying Yai Sheng Lan: The Overall Survey of the Ocean Shores, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press - The Hakluyt Society, 1970 -- The author broaches this same subject. NEEDHAM, Joseph, WANG Ling - LU Gwei - Djen, colls., op. cit. -- Perhaps more than any other author, Needham contributed in placing the debate on the size of Zheng He's ships at an international level. SCHEURING, Hans Lothar, Die Drachenflus-Weft von Nanking: Das Lung-chiang Ch'uan-ch'ang Chih, eine Ming-zeitliche Quelle zur Geschichte des Chinesischen Schiffbaus, in "Heidelberger Schriften zur Ostasienkunde", Frankfurt, 1987, pp. 120-121 -- The author points out the critical position of some Chinese naval architects concerning the great length discussed for Zheng He's ships. BARKER, Richard, The Size of the "Treasure Ships" and Other Chinese Vessels, in "Mariner's Mirror", 75 (3) Aug. 1989, pp. 273-275 -- For the renewed discussion on this subject. INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, Shanghai, 4-8 Dec. 1991 - [Proceedings of...], Shanghai, 1991--The majority of the contributing Chinese researchers sided with the higher proposal for the "Treasure Ships"' size as put forward by researchers from the past like Needham.

Sleeswyk's article from February 1996, published in "Mariner's Mirror", constituted the most recent conclusion on this discussion by Western researchers, sinologues or not. Chinese researchers contacted recently, among them the nautical historian on the Ming period, Zheng Yijun, in Qingdao, and professor Xi Longfei, naval engineer from Wuhan Transportation University, have expressed their confidence in the traditional version inherited from the literal translation of the ancient texts Ming Shi, · an ancient chronicle from the Ming dynasty (four hindred and forty chi, · being around one hundred and thirty seven metres in length).

23 CHEN Xiyu, Investigation on the Unit 'Liao' for Junks in Song Dynasty, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, op. cit., pp. 270-274, p. 270 -- "The number in liao is closely related to that of storage capacity of vessel, [...]." According to this author, the liao is not a unit of weight which has been accepted generally, but is a unit of volume.

24 SLEESWYK, André Wegener, 1996, op. cit. -- The author formulated his new analysis of liao basing it on a comparative summary in an Chinese text from 1553 describing the details of a shipyard in Nanjing. · This text, made accessible to non-Chinese readers by the publication of a book in German on the subject in 1987 (SCHEURING, Hans Lothar, op. cit.) providing a descriptive picture of the various vessels whose size is given in liao, like the length and width and other linear measurement not duly identified. However the vessels thus described would be clearly smaller (four hundred liao) than the "Treasury Ships" of Zheng He (two thousand and one thousand five hundred liao for the two larger types in the fleet from the beginning of the fifteenth century), Sleeswyk used the information for a sophisticated comparative analysis whose only weakness rests in the axiom put forward on the "impossibility" of the existence of wooden vessels over one hundred and twenty metres long.

25 JEZEGOU, Marie Pierre, Eléments de Construction sur Couples Observés dur une Épave du Haut Moyen-Age Découverte a Fos-sur-Mer (Bouchesdu-Rhône), in VI CONGRESSO INTERNATIONAL DE ARQUEOLOGIA SUBMARINA (SIXTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF SUBMARINE ARCHEOLOGY), Cartagena, 1982 - [Actas das Comunicações...], Madrid, 1985, pp. 351-356.

26 FILGUEIRAS, Octavio Lixa, Architectura do Rabelo: Apresentação do Filme Documentário Homónimo, Lisboa, Academia de Marinha, 1993, p.10. In more than one aspect, the construction of the rabelo is reminiscent of a river junk or of a traditional Korean vessel: flat bottoms comprising of several planks, well-spaced ribs built after the hull had been built by joining planks.

27 The period after the Second World War, in which Worcester and Needham developed the main part of their work on Chinese nautical, was marked by a series of attempts with experimental naval archeology revolving around the reconstruction of transpacific voyages in enormous rafts, inspired by ancient rafts from the western coast of Latin America. These voyages and experiments were seen as enriching and revealing with regard to the broad debate to do with this particular type of vessel about which, already in the first half of the twentieth century, the Japanese naval archeologist Shinji Nishimura, had devoted some essential writings to (NISHIMURA, Shinji, Ancient Rafts of Japan, Tokyo, Society of Naval Architects, 1925). Half a century later, archeologists reflected on this subject of vessels reaching such a stage of evolvement as shown in the works of Edwin Doran who broached the question of sea-going rafts from a broad perspective which branched out into Chinese junks (DORAN, Jr., Edwin, The Sailing Raft as a Great Tradition, in RILEY, C. et al., ed., "Man across the Sea: Problems of Pre-Colombian Contacts", Austin - London, University of Texas, 1971, pp. 115-138). It is probable that perhaps such an emphasis given during those years to this field of naval archeology influenced writers like Worcester and Needham who developed the major part of their analysis during that exact period.

28 In Japan, Shinji Nishimura's work stand out, published by the Society of Naval Architects, from Tokyo in the 1920's and 30's.

Also see: DEGUCHI, Akiko, Dugouts of Japan: Hull Structure, Construction and Propulsion, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, op. cit., pp. 197-214 -- For a deeper research into this question. UNDERWOOD, H. H., Korea Boats and Ships, in "Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society: Korean Branch", (23) 1934, pp. 1-100 - An extensive monograph often quoted as a source of reference on the subject of monoxyle canoes and the origins of Korean naval construction. GREEN, Jeremy, The Shinan Excavation, Korea: An Interim Report on the Hull Structure, in "International Journal of Nautical Archeology", 12 (4) 1983, pp. 293-301 -- Where the author reveals some more recent works carried out in Korea. ZAE-GEUN, Kim, The Wreck Excavated for the Wando Island, in INTERNATIONAL SAILING SHIPS HISTORY CONFERENCE, op. cit. pp. 56-58 [1st edition: Seoul, 1980 -- in Korean] -- An English résumé of an original account about the discovery of a vessel from the fourteenth century (around 13 52 or slightly earlier, during the Yuan dynasty) carried out in 1976 near Shinan, in Southeastern Korea.

29 DAI Kaiyuan, Notes on the Origination of Ancient Chinese Junks Based upon Study of Unearthed Dugouts Canoes, in "Marine History Research", Shanghai, (1) 1985, pp. 4-17; XU Yulin, On the Emergence and Operation of Ancient Canoes Judging from the Discovery of Canoe-shaped Earthwares along the Coast of East Liaoning Peninsula, in "Marine History Research", Shanghai, (2) 1986 pp. 1-10.

30 In a recent visit to Southern China, a Germam archeologist admitted being unable to see no more than two traditional junks along the Shantou · (Jobst Broelmann, Deutsche Museum, Munich, 29th of February 1996 -- oral communication). A young Chinese naval archeologist, residing in USA, admitted only seeing one genuine junk during his travels in China (Ben An Liu, 22th of January 1996 -- oral communication). However, Wayne Moran, a navigator and captain of a replica of a junk from the Ming dynasty, during a trip around the Chinese coast, from Hong Kong, in 1990, testified to having come across three fleets of fishing junks with sails while at sea, each one with several dozen sails measuring up to twelve metres.

31 A dock-master in Hong Kong Island, calculated that the last authentic junks disappeared in Hong Kong around 1964-1965, (Martin Leung, Aberdeen Marine Club, Aberdeen, Hong Kong, 18th of March 1996 -- oral communication). Another local technician and naval architect, calculated the "junks" built in Hong Kong since the 1960's were no more than models of Western vessels, for use as recreational boats (Francis Law, Central, Hong Kong, 10th of February 1996-oral communication). For his part, a Hong Kong navigator and captain, added that the last authentic junks to appear in Hong Kong were not built in the territory under the British (Wayne Moran, Shing Ge Fat Shipyards, Aberdeen, Hong Kong, 1 st of March 1996 -- oral communication).

32 Junks of twenty four to twenty seven metres in length were still present in Ainya Island, on the Southern coast of China around 1992-1993 (Martin Leung, Aberdeen Marine Club, Aberdeen, Hong Kong, 18th of March 1996. oral communication).

33 (Mr. Tang, Chongqing, 21th of March 96 -- oral communication).

34 This skipper, now retired, had sailed for forty years along the rivers in this region in the northern Yangzi (Jialing · River, 23rd of March 1996 -- oral communication).

35 An old naval boat builder (Xu Dexian, Qingdao, 26th of March 1996). According to another younger observer from there, the fleet of salt boats in Qingdao numbered thirty vessels with a displacement of up to one hundred and eighty tons. The maximum length probably being just under twenty metres. The fleet anchored in the port was comprised of two types of vessel, the smaller type having an approximate length in the region of thirteen to fourteen metres (observation which took place from a distance, Qingdao, 26th of March 1996).

36 A brief résumé of the observations of vessels around Wuhan (Ha · River, Hanou, · 29th of March l996) leads us to conclude:

1. Wooden vessels of a traditional shape still exist in spite of motorisation and even in sizes over ten to twelve metres,

2. Several manual powered vessels still exist unchanged;

3. in the same type of vessel (wooden cargo junk) one can see precise modifications which do not affect the vessel as a whole even in its final shape (for example the stern poop's shape,

4. the watertight bulkhead system and the construction around them, in the absence of any primary transversal structure like 'mid-ship framework', are used in shipbuilding with steel visible on the sandy shoals on the banks of the Ha River (Hankou, · Wuhan ·), and that

5. Modern Chinese construction even today shows, with modern materials (steel), a valid principle from the past for all constructions out of wood: the vessels' shapes vary enormously within the same type (shape of the prow in present river rafts for example).

37 An engineer (Li Bangyan, Shanghai, 6th of March 1996 oral communication).

This period corresponded to an intensive restructuring of all fishing off the Chinese coast, started at the beginning of the 1950's through clandestine emigration and throughout the reorganisation along the collective model. In Spring of 1958, the 'Great Leap Forward'. was put into action by Mao Zedong. ·

SWANSON, Bruce, op. cit., p. 221 -- According to this author, in 1959 China had achieved "[...] a complete metamorphosis [...]", reaching second place among fishing nations in that year. The Chinese fishing fleet played a role in national defence for a time in the 1960's, with a national fishing militia and the involvement of some of their junks in specific military operations.

38 In the 1960's and 70's (Li Bangyan, Shanghai, 6th of March 1996 -- oral communication).

39 BROELMANN, Jobst, Die 'Sieben-Fächer-Dschunke' und Andere Boote des Taihu-Sees in Südchina, in "Das Logbuch", 1 (30) 1994, pp. 17-26.

40 SLEESWYL, André Wegener, 1996, op. cit., p. 7 -- "There is reason to think that Ming naval architects may have been able to calculate 2/3 powers, because cube root extraction was applied in China since later Han times (907-1124) [...]. That the naval architects took the trouble to give the block volume (lxbxh) may have been for the convenience of those shipwrights whose mathematical skill enabled them to multiply numbers and to extract square roots, but not cube roots [...]."

41 JEFFERY, B., The Steam Lifeboat 'City of Adelaide ": Its past and Future, in "The Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology", 13 (2) 1986, p. 43 -- The author mentions that at the end of the 1880's, in England, there was a fifteen metre long lifeboat, with a displacement of twenty six tons and built with riveted steel, had fifteen of these compartments.

42 Mestre (Petty Officer) (Valente, Maritime Museum, Macao, 15th of March 1996 and 19th of April 1996--oral communications).

43 Types of wood used in "ancient" vessels seen since 1955 by Petty Officer Valente in Macao's Port Authorities: antenna for masts; teak for superstructures, deck and bulkheads; camphor for midship framework; tchau for the prow wheel, keel and stern post; sam tchong for the covering planks. Inside the vessels, Valente added that sam tchong was used for superstructures (as well as some teak) and for bulkheads: sam tchong again for the deck and for quick work: polo cap a, very dense wood, for the upper works and tchau for the keel and midship framework (Valente, Maritime Museum, Macao, 1st of March 1996 -- oral communication).

44 Inquério as Embarcações de Pesca: Fevereiro de 1987: Relatório final, Macau, Direcção de Serviços de Estatística e Censos, 1987, p. 26 -- This written report form the Government of Macao shows (p. 16, quadro (chart) 2 "Distribuição das Embarcações por Tipo e Modelo") that in a total of foutr hundred and eighty eight fishing vessels registered in Macao, four hundred and eighty two belonged to the "modern model" defined by those carrying out the survey as "Western type vessels" while only six followed the "ancient model", defined as "[...] a vessel built according to traditional Chinese methods and models."; apud PEIXOTO, Rui Brito, Dragões no Mar: Os Pescadores Chineses de Macau, Macau, 1989, Bibliography [2nd edition, 1991].

45 PEIXOTO, Rui Brito - OLEIRO, Manuel Barrão, Museu Marítimo de Macau, Macau, Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1992, pp. 86-88--The inscription on the front window of traditional Chinese naval construction of the Maritime Museum of Macau has an identical meaning. It reads: "In Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao, regions of strong relationship with the outside world, have used methods of naval construction for a longtime which reveal a Western influence -- detectable in the type of prow, in the appearance of a small keel, a more raised than rounded stern poop, more numerous midship framework [...]. More typically, it shows a superficial copying, not an adoption of the rudiments of structural methods [...]."

46 The point observed in some shipyards on the banks of the Yangzi River, as in Chongqing, in the upper Yangzi, as in the middle near the city of Wuhan (Ha River), present us with another picture on this subject in showing us steel plated boats in the process of being built in an 'improvised' shipyard on the river's sandy slopes. There were boats without any form of initial transversal structure of the 'skeleton' type. The hull's initial shape and rigidity was determined entirely by a series of vertical bulkheads (of steel plate) whose role resembled that of bulkheads in traditional Chinese naval construction in wood.

start p. 223

end p.