The first study of Macanese history with academic significance was the 1936 publication Zhongpu waijiao shi· (A History of Sino-Portuguese Relations). Despite the title, this book is primarily concerned with the development of Macanese history subsequent to the settlement in Macao of Portuguese traders who came to the East and marauded China's southern territorial waters in search of trade, and the history of the negotiations between China and Portugal which arose as a result. Since the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, Chinese academics, especially modern historians, have focused their study on the history of imperialist intrusion into China, owing to various humiliations suffered by China over the last hundred years. A whole series of works have been written and published, some of which examine modern Chinese history in general, but in the perspective of the history of imperialist intrusion into China. Other publications seek to concentrate the history of imperialist aggression in China as a specialist topic. In the last forty years, the author's own research institute has produced these titles: Meiguo qinhua shi· (A History of American Aggression in China), Diguozhuyi qinhua shi· (A History of Imperialist Aggression in China) — in two volumes —, Sha E qinhua shi· (A History of Tsarist Russian Aggression in China) — in four volumes —, Riben qinhua qishi nian si· (Seventy Years of Japanese Aggression in China), and Shijiu de Xianggang· (Hong Kong in the Nineteenth Century). On top of these are the publications of the many higher education or equivalent establishments in mainland China. The history of the invasions of China by capitalist and imperialist countries such as France, Germany, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, and have all received individual treatment in specialist publications. It is interesting to note that between the 1950s and the 1970s there seems to have been comparatively little study in the history of Portugal's occupation of Macao or of the invasion of the Chinese territory of Macao. As far as the author can ascertain, the number of articles on the history of Macao published during this period did not even run to double figures, and only two or three relevant sources of historical material were produced Putaoya qinzhan Aomen shiliao· (Historical Materials Relating to the Invasion of Macao by Portugal) edited by Jie Zi, · and Diguozhuyi yu Zhongguo haiguan· (Imperialism and Chinese Customs and Tariffs) [6th edition]).

Since the gaike kaifang· (Open Door Policy) was adopted in China in the early 1980s, and especially the negotiations between the Chinese and Portuguese governments on the return of Macao to Chinese sovereignty, more and more Chinese historians have shown an interest in exploring the evolution of Macanese history and the number of publications in this field has increased accordingly. These scholars are located in major cities such as Guangzhou, · Nanjing, · Shanghai, · Nanning· and Beijing. · A tentative estimate would put the number of articles concerned specifically with the history of Macao which have been published in the last ten years at more than fifty, amounting to several volumes. Such publications include Mingshi Folang jizhuan jianzheng· (Key Notes and Commentaries on Buddhist Officials in Ming Dynasty History) by Dai Yixuan, · a scholar of Macanese history from Guangzhou, published in Beijing in 1984; Aomen shi· (A History of Macao) by Huang Hongjian, · a scholar from Nanjing, published by the Hong Kong Commercial Press· in 1989; Aomen sibai nian· (Four Hundred Years of Macao) by Fei Chengkang, · a young scholar from the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, · published in Shanghai in 1990; and Aomen shi gangyao· (An Outline of Macanese History) by Professor Huang Hongzhao, published in Fuzhou· in 1991. The Guangzhou scholars Huang Qichen· and Deng Kaisong· have published the greatest number of articles on Macanese history, and it is understood that Deng Kaisong is soon to publish a book. Aomen gang shi ziliao huibian· (A Compilation of Macao and Hong Kong Historical Materials: 1553-1986) edited jointly by Deng Kaisong and Huang Qichen, was published in 1991. It would seem that the historical study of Macao has caught up with that of Hong Kong.

The study of the history of Macao undertaken in the last ten years by scholars in mainland China has already described the historical development of Macao over the last four hundred years. The research, in the form of published articles and books, has so far encompassed topics such as the following:

1. The arrival of the Portuguese in the East and their settlement in Macao in the sixteenth century,

2. Policy considerations involving the Ming government's decision to allow the Portuguese to lease land and trade in Macao,

3. Special policies implemented by the Chinese government which controlled Macao in the early half of the Qing dynasty,

4. The transformation of Macao during the eighty years of Portuguese rule into a central hub of trade between the eastern and western worlds and the golden age it enjoyed, conflict in the middle of the seventeenth century between Portuguese traders and Japanese, Spanish and Dutch traders,

6. The change in Chinese coastal territory policies and internal conflicts among the Portuguese which led to the demise of Macao's status as an international trading centre,

7. The revival of the Macanese economy with the trade in labour and opium after the beginning of the eighteenth century,

8. The arrival of missionaries and Macao's role as a bridge for international cultural interchange between the East and the West,

9. The conspiracy by the Portuguese colonialists to change the status of Macao after the Opium War, and

10. The conclusion of the Sino-Portuguese Draft Agreement· and Sino-Portuguese Friendly Trade Relations Treaty· in 1887, which altered the status of Macao, the planning by the Chinese government to secure the return of Macao and over one hundred years of negotiations over Macao between China and Portugal.

The views discussed by scholars on the many topics in the course of Macanese history are largely compatible, but despite these similarities in some major issues it would be inaccurate to say that there were not major differences of opinion. The author has set below a discussion of some of the main differences of opinion and problems in the study of Macanese history.

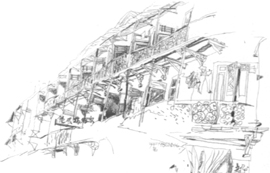

Travessa das Virtudes (Travessa of the Virtues).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/10/16. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0 cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 2.

Travessa das Virtudes (Travessa of the Virtues).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/10/16. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0 cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 2.

§1. THE REASONS BEHIND THE SETTLING OF PORTUGUESE IN MACAO

In his book Zhongpu waijiao shi· (A History of Sino-Portuguese Relations), Zhou Jinglian· lists various different assessments of the settling of Portuguese in Macao. There are two possible scenarios. One possibility is that the Portuguese drove out the pirates which had forcibly occupied Macao and were then either allowed by the local authorities to take up residence as a reward, or else the Chinese emperor gave them Macao to commend them for driving out the pirates. Alternatively, the Portuguese paid large bribes to local officials, such as the haidao fushi· (deputy maritime envoy) Wang Bo, · in return for permission to reside in Macao.

Chinese scholars are largely in disagreement with the idea that the Portuguese won Macao by banishing pirates, and are unable to support it with material historical evidence. Jie Zi, · the editor of Historical Materials Relating to the Invasion of Macao by Portugal is of the opinion that this explanation, nothing more than other, is a shameless fabrication on the part of the Portuguese colonialists. In An Outline of Macanese History, Huang Hongzhao specifically scotches any mistaken claim that the Portuguese obtained Macao by beating pirates. He points out that Macao has no record of being pirates'haunt. Fei Chengkang, author of Four Hundred Years of Macao, is likewise opposed to the idea that the Portuguese drove pirates from Haojing· and then set up their 'colony' there. Chinese scholars generally concur in the opinion that the Portuguese managed to settle in Macao as a result of bribing local officials. But whether or not their presence had the approval of the Ming government is an issue for which scholars have a variety of explanations. Jie Zi thinks the Ming government gave no such approval.

Huang Hongzhao and Fei Chengkang quote from a letter which Captain Leonel de Sousa wrote in January 1556 to Portuguese prince Dom Luís [sic] as evidence that the Portuguese bribed deputy maritime envoy Wang Bo assisted by Chinese traders. They abused their status as foreigners to purport that they were prepared to pay any tax the Ming government required and that they had come to Guangdong· in search of trading opportunities. Wang Bo presented a report to the Imperial Court in 1553 and received approval in 1554 to trade with the Portuguese, which secured an opportunity for the Portuguese to come to Macao to trade. If this explanation is to be believed, then the Portuguese came to Macao with the approval of the Imperial Court. However, no support for this idea is to be found in Chinese historical archives. Fei Chengkang goes on to say that "[...] the Portuguese did not have the official permission of the Ming government and lived in Haojing for almost a decade**and after this paid land rent to the local government." Fei thinks that "[...] the payment of land rent by the Portuguese to the local government proves once again that the Portuguese recognized that Haojing was Chinese territory. The ground rent which they paid to the Chinese government was duly recorded in the Guangdong fuyi quanshu· (Guangdong Tax Register), which has been in publication since time immemorial, which is an indication that the local Chinese authorities had given the Portuguese formal permission to reside in Macao". Fei Chengkang also cites historical material to the effect that, in 1582, the liangguang zongdu· (Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi·), Chen Rui, · allowed the Portuguese to continue to reside in Macao after he had received a bribe, but that they were obliged to "[...] obey the jurisdiction of Chinese officials." This led Fei to conclude that this, in fact, was the first instance of a feudal provincial ambassador to the Ming government actually giving the Portuguese permission to take up residence in Macao.

If fact, not long after the Portuguese had appeared in Macao, the Chinese local authorities began an internal discussion over whether the Portuguese traders really had Government approval. In 1614, Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi, Zhang Minggang· reported that in his opinion the best way of dealing with the Portuguese was not to expel them forcibly, but was to take advantage of their predicament in being "[...] dependent on [the Chinese] day and night, [... to] impose Ming order and regulations, [...]" within a view to increasing the degree of circumspection and supervision. This suggestion may have met with the approval of the Imperial Court. In his article Yapian zhanzheng qianhou Aomen diwei de bianhua· (The Changing Status of Macao at the Time of the Opium Wars), published in the 3rd issue of "Jingdai shi yanjiu"· ("Modern Historical Research"), in 1983, Wang Zhaoming· suggests that "This is the earliest indication we have of the Imperial Court's attitude regarding the issue of the occupation of Macao by the Portuguese."

Broadly speaking, it appears that the following conclusions have been drawn concerning whether the Portuguese occupation of Macao had the sanction of the Imperial Court:

1. Approval was granted by the Imperial Court in 1554,

2. Formal payment of ground rent occurred twenty years later in 1573, which can be interpreted as approval,

3. Formal approval was given by Chen Rui when he was appointed Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi in 1582, this being corroborated by the entry of this payment in the Guangdong Tax Register at roughly the same time, and

4. The Imperial Court approved Zhang Minggang's 1614 proposal.

It seem untenable to suggest that the Ming government did not grant approval.

§2. DESCRIPTIONS OF PORTUGUESE PRESENCE IN MACAO

The Portuguese presence in Macao is traditionally described by Chinese scholars as "incursion", "occupation", "invasion" or alternatively by some writers, Chinese and others, as "colonization". Jie Zi's publication Historical Materials Relating to the Invasion of Macao by Portugal expresses a quite unambivalent opinion. In Aomen wenti de lishi huigu· (A Historical Review of the Macao Problem) published in the 1st issue of "Nanjing daxue xuebao"· ("Journal of the Nanjing University"), in 1987, Huang Hongzhao divides the Portuguese invasion of Macao into three stages:

1. During the period 1517 to 1557, the Portuguese bribed the Chinese authorities to open up Macao and let them trade,

2. From 1557 to 1849 was a period of forcible residence and control of trade in Macao, and

3. After 1849 Chinese authority was eroded and a period of direct colonial control of Macao began.

The view that Macao was invaded by Portugal is also supported by Ding Mingnan· in the first volume of A History of Imperialist Aggression in China, published in 1958. This is quite natural and understandable. The invasions by major powers which China suffered after the Opium Wars were truly grievous.

From the viewpoint, mentioned above, of the Ming government towards the Portuguese presence in Macao, the local Chinese authorities gave tacit approval in 1553, the Chinese local government collected ground rent in 1573, the Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi gave permission in 1582 but it was not until 1614 that the Ming Imperial Court gave its consent for Portuguese to reside in Macao. At that time the Portuguese traders had not yet forced the Chinese government to accept their forcible intrusion, so the Chinese government at the end of the Ming dynasty had to reason to fear the Portuguese traders. In Fei Chenkang's analysis, the Ming government's assent to Portuguese residency in Macao had some connection with the activities in Chinese coastal waters by Japanese pirates and the infamous pirate He Yaba· from Dongwan. · Moreover, permission was given in the knowledge that collecting taxes from Macao would benefit local revenue. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the Portuguese had intended to use military force to disregard Chinese customs requirements, but met with major setbacks at Tunmen· and Xicao· harbours in Guangdong and also at ports in Fujian· and Zhejiang. · This prompted them to concede that they were powerless in the face of China's strength to defy Chinese customs by force. Instead, they adopted the peaceful means of negotiation and bribery to secure an opportunity to enter China and trade. However, once the Portuguese had settled in Macao, they complied with the Chinese government administration. This was the situation for about three hundred years. This is in stark contrast to the "invasions" of China by the major powers in the middle of the nineteenth century. Fei Chengkang is not content to use the term "occupation", since in his opinion the three hundred years of history leading up to the Opium Wars was not a period of Portuguese "invasion" but of "harmony" based on friendly relations and cooperation between China and Portugal. This is a point which deserves further academic research.

Av. de Almeido Ribeiro (Ave. of Almeido Ribeiro).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/12/15. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 5.

Av. de Almeido Ribeiro (Ave. of Almeido Ribeiro).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/12/15. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 5.

It is also difficult to support the proposal that Macao was a Portuguese colony during this period. Macao differed from Portugal's other overseas colonies. The Chinese government's sovereignty over Macao was in no way impeded. In an article entitled Shiliu zhi shiqi shiji Zhongguo zhengfu dui Aomen de teshu fangzhen he zhengce· (The Chinese Government's Special Policies Relating to Macao from the Sixteenth to the Nineteen Centuries) published in the 6th issue of the Guangxi· periodical "Xueshu luentan"· ("Academic Forum"), in 1990, Huang Qichen analyses this issue in detail. In his view Chen Rui, · the Governor General of Guangdong and Guangxi in 1583, gave tacit approval for the Portuguese in Macao to set up a municipal legislative assembly. A senior official was appointed by the Ming government in the role of yimu· (Supervisor of Foreigners) who was responsible for representing the Chinese government and overseeing the self-admninistration affairs of the Portuguese within the city walls and on the southern edge of the peninsula. This Portuguese self-autonomy did not extend beyond the Portuguese community and was restricted to affairs within the Portuguese community. The Chinese government ruled the whole of Macao effectively throughout and the Portuguese in Macao fully accepted the authority of the Chinese government. Fei Chengkang reasons that by allowing the Portuguese a degree of self-autonomy the Ming government was emulating the method established in the Tang and Song dynasties of managing the foreign neighbourhoods in Guangzhou inhabited by expatriates. It follows then that Macao during this period was, in the words of Huang Qichen,"[...] a special territory like an island under direct Chinese sovereignty and rule which the Portuguese administer trade." So, the proposal that Macao was a Portuguese colony before the Opium Wars cannot be justified.

§3. THE IMPACT OF THE PORTUGAL ADMINISTRATION OF MACAO ON CHINESE HISTORY

This is an engaging topic on which scholarly opinion tends to be divided. In their joint publication Mingqing shiqi Aomen duiwai maoyi de xingshuai· (The Rise and Decline of Foreign Trade in Macao in the Ming and Qing Periods) published in the 3rd issue of the journal "Zhongguo shi yanjiu"· ("Chinese Historical Research"), in 1984, Huang Qicheng and Deng Kaisong have analyzed the causes of changing fortunes in Macanese foreign trade between 1553 and 1911, placing special emphasis on the way this trade influenced Chinese history. The article states that the flourishing of the docks and foreign trade in Macao was controlled by the Portuguese and other colonial countries. Since the trade was mainly savage, exploitative plunder, its effect on China's economy cannot be said to be advantageous. On the contrary, it was detrimental, a fact which became more and more evident after the fall of the Qing. The Portuguese colonialist control over Macao foreign trade greatly exarcebated the problems and dangers faced by Chinese traders who relied on Macao's foreign trade. The result was that Chinese foreign trade was only able to develop very slowly if at all which had severe implications for the economy of China's feudal society. Not only was the development of China's production of commercial goods harmed, but China was rendered incapable of accumulating sufficient means of generating currency from foreign trade conducted through Macao. This consigned a certain number of cottage industry enterprises, which had sprouted in an atmosphere of capitalism, to long-term stagnation. This can be construed as one of the main reasons why China began to lag behind Western Europe from the sixteenth century onwards.

Huang Qichen went on to conduct a fresh inquiry into this issue and offered an unprecedented discussion on it. While researching the consequences of the Chinese government's policies relating to Macao between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, he pointed out that the consequences were indeed severe but had direct implications. One severe consequence was the Chinese government's loss of sovereign rule in political terms over Macao after the Opium War. In economic and cultural terms, the direct implications mainly concerned the development of China's commercial and monetary economy and the advancement of technological and cultural exchange between China and the West. As for economy, Huang's article points out that during the seventy-two-year period from 1573 to 1644, Portugal, Spain and Japan imported silver to a value of fourteen million yuan· into China. As a bimetallic currency standard based primarily on silver and secondarily on copper has been established in China since the middle of the Ming dynasty. This created conditions such that the Ming government's implementation, in 1581 (Wanli· reign, year 9), of a nationwide single assessment law which imposed a silver tax calculated on the basis of land ownership could be executed successfully. "This law established the prevalence of taxation in monetary form, something which went on to be of great significance in the modern era." (See: HUANG Qichen, The Chinese Government Special Policies Relating to Macao from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries -- already mentioned). In an article Mingqing zhiji de Aomen shi Zhongxi wenhua jiaoliu de qiaoliang· (Macao in the Ming and Qing Dynasties as a Bridge for Cultural Exchange in China and the West), Beijing academic Liu Zhongri, · also cites historical evidence to show that the Portuguese traders controlled Macao's international trade, which promoted and stimulated the production and circulation of Chinese goods, which reinforces the point made above. Liu thinks that the fact that the large quantity of silver came into China through Macao undoubtedly benefited the developing commodity economy, and that in fact contributed like an additive to the monetary economy of the time and acted as a catalyst to stimulate the production of goods. This was an increasingly significant factor which fertilized the seedlings of capitalism which sprang up on the cusp of the Ming and Qing dynasties in the Yangzi· and Pearl River delta areas (See: WU Zhiliang, · ed., Dongxifang wenhua jiaoliu· (Cultural Exchange between East and West), Macao, Fundação Macau (Macao Foundation, · 1994). In a paper which he presented at the SEMINÁRIO INTERNACIONAL SOBRE INTERCÂMBIO CULTURAL OCIDENTEORIENTE (INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON EAST-WEST CULTURAL INTERFLOW), held in Macao on 2nd-5th of March 1993, entitled Chongxin pinggu Aomen zai Dongxifang wenhua jiaoliu zhong de diwei· (A New Assessment on the Role of Macao in Cultural Exchange between East and West), Fei Chengkang supports the view outlined above. In his opinion, from the time when Portuguese first became involved in Macanese trade until 1849, despite the inevitable moments of friction, no serious military conflict arose between China and Portugal and the two countries maintained consistently friendly relations. Moreover, before the English began importing large quantities of opium into Macao in 1799, the East-West trade conducted through Macao was honest and fair. The trade was extremely beneficial to China, especially during Macao's golden age which lasted nearly eighty years. It stimulated production of merchandise in China's cities and towns and the economic strength of these areas. "This is why by the eighteenth century, no matter what complex effects this trade route which stretched round the Cape of Good Hope had on other regions of the world, its operation most definitely benefited the progress of Chinese society."

Rua das Lorchas (Street of the Lorchas).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衞鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/10/4. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0 cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 1.

§4. ASSESSMENT OF MACAO'S STATUS IN HISTORY

Given that Portugal has occupied Macao for a long time, mainland Chinese scholars' evaluation of Macao's status in history is usually somewhat low. In recent years, researchers of Macanese history have adopted a rather sober attitude in their approach. The "occupation" of Macao by Portugal in 1849 and especially after 1877 does not negate Macao's four hundred years of history. The fact that opium and coolie trades picked up in Macao in the nineteenth century and turned Macao into the Monte Carlo of the East were not the reason for the decline of Macao's standing in international trade. Scholars have evaluated Macanese history since the middle of the sixteenth century and Macao's importance in international trade in various ways and divided the period into various stages. Most scholars stress Macao's significant role between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries as a port in trading routes between Asia, Europe and America and in China's foreign trade as a point of contact for international cultural exchange. Huang Qichen, Liu Zhongri, Huang Hongzhao and Deng Kaisong all discuss these points. Fei Chengkang goes one step further to say that during Macao's Golden Age, which lasted for eighty years after the port was first opened, Macao was more important even than Guangzhou, Nagasaki, Manila, Malacca and Batavia. He says that Macao was the Far East's most famed distribution centre for trading goods and China's most important transport link with the rest of the world (See: FEI Chenkang, Four Hundred Years of Macao -- already mentioned).

People have attached excessive importance to the Silk Road, the overland trading route with its origins in Chang'an. · In his article A New Assessment on the Role of Macao in Cultural Exchange between East and West, Fei Chengkang has considered the issue of Macao's historical status in a broader perspective. His assessment amounts to an appeal for Macao to be accorded the star role on the stage of cultural exchange between East and West. Fei proposes that trade conducted through Macao was greater in volume, broader in scope and more elaborate than on the Silk Road. On these grounds, the cultural role and importance of the Silk Road was inferior to Macao's standing in cultural exchange between East and West as a gateway of the major shipping routes. Fei also posits that before the Opium Wars, China only had two major routes for communication with the West. One, the Silk Road, originated in the ancient city of Chang'an and cut through the desert and mountain ranges to arrive at the eastern coast of the Mediterranean. From the beginning of the Western Han· dynasty until the end of the Ming period, the Silk Road was the major route for trading and cultural links with the West. But this ancient route came to be plugged up half way along by the Ottoman Empire. The other route was a direct shipping route to East Asia which was opened up in the late fifteen and early sixteenth centuries when the Portuguese sailors first rounded the Cape of Good Hope and navigated the Strait of Malacca. China was able to recover links with the West through the ports of Guangzhou and Macao. During the period of three hundred years from the middle of the Ming dynasty until the early Qing, this route became the major trading route between China and the West. Considering the issue in this light, it is clear that Macao's Golden Age in the Ming era put Macao on a par with the ancient city of Chang'an in terms of importance in communication with the West, and that from then up until the Opium Wars remained China's only point of communication between China and the West, roughly equivalent to Dunhuang· on the Silk Road.

After the Opium Wars, Macao's status began to decline when it was superseded by Hong Kong and Shanghai. Owing to the subsequent invasions by foreign powers and the Imperial Court's disappearance into obscurity of intrigue, confusion and weakness, the Portuguese were able to seize the opportunity to strip the Chinese government of its administrative authority over Macao such that in 1887, beset by a complex situation in international affairs, the Chinese government agreed to a treaty which granted Portugal the power to "[...] reside in and administer Macao in perpetuity [...]" with the proviso that Portugal should never without authorization allow possession of Macao to pass to another country. Although the Chinese government eventually lost all its authority in Macao, we cannot ignore the Ming government's Macao policy three hundred years earlier, or deny that the Chinese government cooperated in the process by which the Portuguese came to run Macao. Nor can Macao's rightful importance in the history of cultural interchange between East and West be dismissed. This is why Fei Chengkang asserts that: "Notwithstanding the five thousand years of civilization in China, Macao is undoubtedly one of the most significant hubs of interaction between East and West in China's history." Researchers can continue to debate and revise Fei Chengkang's conclusion and assert their own opinions. [...]

It can be seen from the above discussion that in the last ten years the study of Macao's history by mainland Chinese scholars has advanced in leaps and bounds. The basic sequence of events in Macanese history has been described. But in my humble opinion, they remain a number of problematic issues in the field of Macanese historical research.

Rua da Felicidade(Street of Hapiness).

UNG VAI MENG 吳衛鳴 WU WEIMING

1986/12/22. Pencil on paper. 38.0 x 29.0 cm.

In: Ung Vai Meng: Desenhos - Drawings, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1989, ill. no 3.

Firstly, much hard work burrowing around the historical archives remains to be done. Chinese scholars have already done a considerable amount of work using archive materials in Chinese, and naturally there are historical materials which have yet to be unearthed. It is particularly important to point out that virtually none of the scholars in China who research the history of Macao have command of the Portuguese language. It is therefore very difficult for them to make use of historical materials in Portuguese, which is most regrettable. If no use can be made of Portuguese archive material, it is clearly quite impossible to research fully the four centuries of Macao's history or to have a full understanding of the important issues raised by it. For instance, Chinese scholars and Portuguese scholars have different views concerning the issue of sovereignty of Macao. According to Chinese scholars, as proved by Chinese language materials, before 1849 the Chinese government's sovereignty over Macao was unrestricted, the Ming and Qing governments adopted special methods in their rule over Macao, one of which was their policy allowed the Portuguese who were resident in Macao to set up a legislative assembly to manage their own affairs. After the 1887 Friendship and Trade Treaty, the Portuguese assumed sovereignty over Macao, but in practice, Portugal's authority over Macao was not without limitations: according to the treaty, Portugal could not dispose of this sovereignty in any way without China's consent (as stated above). In the view of Portuguese scholars, the Portuguese enjoyed a degree of sovereignty over Macao from the middle of the sixteenth century onwards, which constituted an important aspect of Portuguese presence in Macao. We know that before 1887 or 1849 the Portuguese in Macao made consistent attempts to secure sovereignty over Macao, but without success. If scholars could do research work which compared the entire body of Portuguese and Chinese historical archives pertaining to the sovereignty over Macao and conducted an analysis of pre-nineteenth century concepts of international law, our knowledge of this topic might deepen. In any case, if Chinese researchers were free to read Portuguese materials kept in Macao over the last four hundred years and had free access to the historical archives kept by the Portuguese government relating to the Sino-Portuguese relations, the study of Macao's history would benefit immeasurably.

Secondly, much hard work needs to be done if the analysis of Macao's role in history is to be found generally acceptable.

Mention was made above of the influence Macao had on the course of Chinese history. Some say it promoted China's development, others that it thwarted it; others that the main effect was negative and that the benefits were secondary. Some say that it obstructed the development of the early signs of capitalism in China, others that it fertilized the seeds of capitalism. The opinions of academics may be clear-cut, but in every case it is felt that the historical evidence to support them is insufficient and the analysis is suspect according to methodological doctrine, which renders them unconvincing. Attention is drawn by scholars to the implementation in the Ming dynasty of the single assessment law which imposed a tax payable in silver. This law effected the change from taxation in kind to taxation in currency form and in turn benefited Macao, through which a total of more than one hundred million taels of silver flowed into China. Scholars base this statement on statistics calculated by the renowned scholar Liang Fangzhong. · In his article Mingdai guoji maiyi yu yin de shuchuru· (International Trade and the Import and Export of Silver in the Ming Dynasty) published in the 2nd issue of the 6th volume of "Zhongguo shehui jingji shi jikan"· ("Collected Papers on Chinese Social and Economic History"), Liang Fangzhong calculated that during the seventy two years from 1572 to 1644 approximately one hundred thousand taels of silver were imported through Macao. However, the Ming single assessment taxation law was implemented in 1581, merely eight years into the period from which Liang Fangzhong made his calculations. The supposed surplus of one hundred million taels of silver could not have accrued wholly, or even mostly during this eighty year period.

We know that a large quantity of silver came into Macao during the golden age of Macanese trade, but once trade in Macao was on the wane it was the case that silver flowed in the opposite direction out of Macao. The rise and decline of trade in Macao, the volume of that trade and the import and export of silver are the topics which deserve solid and reliable further research which could be used to assess the cumulative role of Macao's international trade in the origins of capitalism in Western Europe and the sociological and economic effects this had on China. Otherwise what we have is feeble and without substance. In my view, this captures the profundity and the problematic nature of the study of Macanese history. If this issue can be tackled, the problem of how to evaluate the historical importance of Macao will be easily solved. [...].

Translated from the Chinese by: Justin Watkins

**Editor's note: this should read "nearly two decades".

* Director of the Institute of Contemporary History• of the Academy of Social Sciences of China•