This paper begins to address the Jesuit development of linear perspective and its intellectual context in the late sixteenth century. It intends to reconstruct the domain of cultural conditions in which Jesuits developed their scientific impulses in the pursuing of metaphysical vision through perspective. Examining this period of thoughts, I would argue that they may shed light on Jesuits' imperatives of regarding perspective as a rational construction of Divine vision to establish symbolic order. Then, the paper discusses the instrumental role of Giuseppe Castiglione (°1688-†1766) in introducing the science and technique of European art to China. Particularly, Castiglione worked as an architect of the Baroque section of the Yuanmingyuan· (Garden of Perfect Clarity) a section of the vast 'summer' complex, north of Beijing, of the Chinese emperors of the Qing dynasty, and was the tutor of the Chinese translations (1729 and 1735) of Andrea Pozzo's (°1642-†1709) Treatises On Architecture1(Perspectiva Pictorum er Architecture 2 vols., 1693 and 1700)

The technique of linear perspective was first transported through Portuguese sea-routes by Jesuit missionaries to the East for their scientific and liturgical teaching. Jesuit perspective is also known as the 'distance-point method,' which designates distance points as references in making perspective imagery. The practical value of the distance-point method lies in its ability to refer to a fixed position, which defines the distance of the observer from the object, without determining vanishing points in constructing and construing perspective images. Locating distance points is essential to the graphic procedure of Jesuit perspective for construing and constructing perspective effects of images, thoughts and places. As a graphic representation of imagery, Jesuit perspective is related to the meditation of 'Spiritual Exercises' to visualize the image of God.

§1. A DISTANCE POINT IN MEDITATION: PERSPECTIVE AS AN EPIPHANY OF IMAGES, THOUGHTS AND PLACES

In general, Catholicism of the Counter-Reformation developed an effective mechanism in visual communication and representation. Through the emotional stimuli of the Divine imagery of art, the believer was supposed to grasp the meaning of the liturgical teachings of the Church, In particular, two types of imaginative processes employed by the Jesuits were:

1. Starting with visual imagery to derive its verbal expression, and inversely, and

2. Beginning with the Word to arrive at visual images.

The later is particularly emphasized.

At the very beginning of his Ejercicios espirituales (Spiritual Exercises) (Rome, 1539-1541), Ignatius of Loyola (° 1491 -† 1556) prescribed internal ordering to proceed to "[...] visual composition, seeing the place [...]" in terms that might also be instructions for the mise-en-scéne of a theatrical performance: "[41 ] The first prelude is composition [,] seeing the place.

It should be noted at this point that when the meditation or contemplation is on a visible object, for example, contemplating Christ our Lord during His life on earth, for He is visible, the composition will consist of seeing with imagination's eye the physical place where the object that we wish to contemplate is present. By the physical place I mean, for instance, a temple or mountain where Jesus or Our Lady is, depending on the subject of the contemplation."2

In this passage, locus (place) and imago (image) are obviously referenced here as the two basic ingredients of the Ars memorativa (The art of memory), adapted to suit the subject and specific objective of each of the four weeks of Spiritual Exercises. For Ignatius, the internally ordered 'composition' of vision is the prelude to meditation in the memory theatre, practised in the sixteenth century.

The Ignatian meditations call for the exercise of artificial memory rather than of natural memory in the mnemotechnical notion of the Ars memorativa. The description of loci (places) and imagines (images) of the Ignatian Spiritual Exercises are based on the Scriptural narrative. The loci, for instance, consist of a variety of places appropriate to meditation rather than of the specific temple/theater typical of the Ars memorativa, in which mnemonic notae or imagines are placed and subsequently plucked out at the appropriate time. Ignatius provides these memory 'points' through language to describe how to imagine images absent from Spiritual Exercises. His insistence on meditation in the memory theatre has one clear aim: to extract the pure and original image in perfect solitude, the divine image through which God's signs will appear, which will then turn to language and return to the public domain. Thus Ignatian procedure of meditation is distinguished among other contemporary forms of devotion by the shift of memory 'movement' from the Word to the visual image as a way of attaining the most profound knowledge.

More intriguing, Jesuit liturgical teachings reverse the direction of meditation stated in the Spiritual Exercises from a given image proposed by the Church itself and not first 'imagined' by the believer to liturgical meaning; memory moves from the imagery to the Word. Points of departure and arrival for the 'composition' of vision are already established by a carefully designated image, but en route "[...] there opens up a field of infinite possibilities in the application of the individual imagination, in how one depicts characters, places and scenes in motion [...]."3 This motion of memory is best illustrated by Hieronimus Nadal's (°1507-†1580) supervision in the liturgical book Evangelicae historiae imagines [...] (Images of Spiritual History [...]) (Antwerp, 1593), in which engravings illustrate biblical scenes in perspective and by which the believers begin to access imagining and remembering as practiced by a sixteenth century man like Ignatious. Even Matteo Ricci (°1552-†1610), had to rely on Nadal's book to demonstrate pedagogically the image of God in his liturgical teaching in China. 4

Stage set with rhombic prisms.

In: DUBREUIL, Jean, La Perspective pratique par un Parisien religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus, 3 vols., Paris, vol.3, p. 104.

Stage set with rhombic prisms.

In: DUBREUIL, Jean, La Perspective pratique par un Parisien religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus, 3 vols., Paris, vol.3, p. 104.

To deal with the supernatural as if it were sensible reality was in agreement with the religious basis of the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius, which teach spiritual comprehension through the use of sense. For a Jesuit, meditation has an affinity with the metaphysical construction of distance points in perspective for obtaining visibility in memory and imagination, which aims at the epiphany of images, thoughts and places. With memory objects as images, rather than words, the Jesuit art has particular interest in classical and mnemotechnical use of Ars memorativa for religious purposes. Although Jesuits never claimed a style of art as their own, their interests in imagery have enobled theories, technics, and techniques of perspective in their literature, painting and architecture to propagate their liturgy in an analogous relationship with Ignatian composition of vision by guiding the believer's spiritual life with an adequate and faithful; depiction of biblical scenes.

§2. SEARCHING FOR THE DISTANCE POINT: PERSPECTIVE AS KNOWLEDGE ABOUT THE ABSOLUTE

The overwhelming importance which Ignatius accords to the sense of sight follows Cicero's precept of insisting upon the use of "corporeal similitudes" with his imagines and provides evident links with the Ars memorativa, not in its classical notion, but as transformed in the Middle Ages to serve purely religious ends, particularly by St. Thomas Aquinas (°1225-†1274). 5 When St. Thomas Aquinas derived scholastic thought from Aristotle (0384-†32BC), he made it possible to reconcile scientific/rational sphere of reason with the theological sphere of knowledge through revelation. Although Renaissance Aristotelianism and Hermetism still permeated seventeenth century Catholicism, the Church, confronted by the Reformation and challenged by the Copernican system, propelled scholastic interest into discerning the truths of reason in nature, together with finding the truths of revelation in the Book of Genesis.

Among orders of the Church, the Jesuits were particularly interested in Aristotle's "first principle" as the conjunction of form and matter, or the meeting 'point' of images and words. The Jesuits' concern with the link between images and words coincides with a prevailing scholastic inquiry of the seventeenth century, which assumed that one might unlock the order of things by studying the logic, geometry and language of the visible world just as Adam did when naming the creatures of the Earth. In this regard perspective was considered by the Jesuits as a geometric construction of vision, an effective tool to make visible what is invisible. The conventional distance-point method of perspective began to be known as "Jesuit Perspective" for it was widely practised and studied by the Jesuits. For the Jesuits, searching for a distance point has a theological affinity with the scientific conviction of finding an Archimedean point to which we can ultimately appeal to determine the nature of rationality, knowledge, truth, reality, goodness, or rightness.

As the Age of Reason flourished throughout seventeenth century Europe, China became a fashionable reference for European intellectuals to assess the progress of Western civilization, literally and figuratively. The Jesuits' correspondences and publications became important sources providing Europe with the updated knowledge of China. In his Preface to the Novissima Sinica (Latest News of China) (Leipzig, 1967 and 1699), Gottfried Wilhem Leibniz (01646-†1716) wrote:

"In the useful arts and in practical experience with natural objects we are, all things considered, about equal to them [the Chinese], and each person has knowledge which they could with profit communicate to the other. In profundity of knowledge and in theoretical disciplines we are their superiors. […] The Chinese are thus seen to be ignorant of that great light of the mind, the art of demonstration […] which our artisans universally possess. 6 [Then Leibniz concluded:] But there is no doubt that the monarch of the Chinese saw plainly what in our part of the world of Plato formerly taught, that no one can be educated in the mysteries of the sciences except through geometry. Nor do I think the Chinese […] have failed to attain excellence in science simply because they are lacking one of the eyes of the Europeans, to wit, geometry.

Although they may be convinced that we are one-eyed, we have still another eye, not yet well enough understood by them, namely First Philosophy. Through it we are admitted to an understanding even of things incorporeal."7

Like most seventeenth-century mathematicians attempting to discern space within the Church's doctrines, Leibniz identified projective geometry as a scientific foundation for the demonstration of knowledge. 8 through the demonstration of perspective drawing, especially the science of perspective, an object and its parts can be defined by spatial sequences, controlled by geometrical orders, and measured by projective scales. Without the invention of drawing, scientific and technological principles would have failed to achieve their current conceptual and perceptual status. Similarly, without the science of disegno (drawing), linear perspective and chiaroscuro might only produce 'realistic' effects without definite, measurable attributes. The visible realms of technology and science entail a conceptual contrast and a Jesuit connection between East and West. Their differences reflect the anthropocentric development of architectural thinking and its practices in the West, specifically recognizing the power of drawing as an epistemological process of demonstration.

Leibniz realized that the one-eyed state of being, or monocular vision, constitutes the foundation for the science of perspective and the perspectival view of the world, in which the order of things is in convergent or divergent relationships to the focal point. What interested Leibniz most had more significance in the perspectival world view than perspective drawing in use. The search for the hidden order of the world belonged to his ardent pursuit: man's understanding of God's world. To be able to comprehend the world at one glance was considered as the beginning of ordering things in isotropic space. Rejecting the dualism of Descartes and the monism of Spinoza, Leibniz instead stressed plurality, harmony and a higher-order unity that could be grasped by reason, and expressed in a logically simple language. For example: Leibniz believed that his binary arithmetic, using '0' and '1' symbols as basic notions, was theologically and scientifically important to unlock the secrets of nature and The Book of Genesis.

The Xieqiqu 諧奇趣 (Delight anf Harmony) pavilion.

One of the Xiyanglou pavilions conceived by Giuseppe Castglione.

Present-day ruined condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Xieqiqu 諧奇趣 (Delight anf Harmony) pavilion.

One of the Xiyanglou pavilions conceived by Giuseppe Castglione.

Present-day ruined condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Huayuanmen 花園門 (Garden Gate) pavilion - partial view.

A corner section of the walled labyrinth's enclosure, seen from above. on the Xingting (Strollers) kiosk's terrace.

Present-day restored condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Huayuanmen 花園門 (Garden Gate) pavilion - partial view.

A corner section of the walled labyrinth's enclosure, seen from above. on the Xingting (Strollers) kiosk's terrace.

Present-day restored condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

Leibniz's first reference to Chinese thought was in 1670, in a letter to the German Jesuit Athanasius Kircher (°1601-†1680), a Hermetist who believed China's civilization was derived from Egypt's. 9 Jesuit scientific writing during the second half of the seventeenth century was dominated by the work of Kircher and his followers. Kircher was one of the most remarkable men of his time. He published forty major works in Latin on topics ranging from the natural sciences to Oriental studies. Kircher's occult philosophy was a blend of science and Renaissance Hermetism combining empirical observation with magical and religious elements.

In 1667 Kircher wrote China monumentis qua sacris qua profanis illustrata (China illustrata). 10This book provided Europeans with a pictorial introduction to the Chinese Empire and its neighbouring countries. Kircher drew on written Jesuit sources, on oral accounts by returning missionaries, and on other sources such as Marco Polo. For almost two hundred years, China illustrata was probably the single most important written and visual source for shaping the Western imagination of China and its neighbours. This book gives a candid glimpse of the old China before the arrival of the Europeans, and portrays the changes and the turmoil caused as Western ideas began to percolate into Chinese society. Momentously, it also shows how China appeared to be through the eyes of the first European missionaries and travelers.

Not only was Kircher a foremost linguist of his day, but he was passionately interested in the origin and development of language. He was convinced that all tongues were basically similar, since they proceeded from the original language which God gave to humankind with the gift of speech. This would explain his concern with seeking to establish an 'authentic' reading, since he was dealing with times before the division of tongues. 11 For Kircher's intellectual and religious interest, the hieroglyphic characters of the Chinese were strong evidence for addressing the Biblical link between East and West. In Part VI of China illustrata, Kircher states:

"I have said that about three hundred years the flood ion the time when the sons of Noah dominated the Earth that the first inventor of writing was the Emperor Fohi […]. In the first book of my Oedipus it is told how Cham first came from Egypt to Persia and then planted colonies in Bactria. 12 […] Bactria is the farthest Kingdom of the Persians and it borders on the Mongol or Indian Empire. It is opportunely situated for the colonization of China, which was the last place on earth to be colonized. At the same time the elements of writing were instituted by Father Cham and Mercury Trismegistos, the son of Nasraimus. Although they learned them imperfectly, they were able to carry them to China. The oldest Chinese characters are a very strong argument for this, for they completely imitate the hieroglyphic writings."13

In the field of architecture, Kircher published two important works: Arca Noe (The Ark of Noah) (Amsterdam, 1675) and Turris Babel (The Tower of Babel) (Amsterdam 1679). The Ark of Noah was the first of the mystical structures of the Old Testament, and its configurations had been directly inspired by God. Like the Tabernacle of Moses and the Temple of Solomon later, the Ark built by Noah prefigures the Church. Its destiny is plainly symbolized by the manner in which the Ark, after many vicissitudes based on Superbia, necessarily had to end in Confusio.

The Huayuanmen 花園門 (Garden Gate) pavilion - partial view.

A corner section of the walled labyrinth's enclosure, seen from above, on the Xingting (Strollers) kiosk's terrace.

Present-day restored condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Huayuanmen 花園門 (Garden Gate) pavilion - partial view.

A corner section of the walled labyrinth's enclosure, seen from above, on the Xingting (Strollers) kiosk's terrace.

Present-day restored condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Xieqiqu 諧奇趣 (Delight anf Harmony) pavilion.

One of the Xiyanglou pavilions conceived by Giuseppe Castglione.

Present-day ruined condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

The Xieqiqu 諧奇趣 (Delight anf Harmony) pavilion.

One of the Xiyanglou pavilions conceived by Giuseppe Castglione.

Present-day ruined condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

Kircher's reconstruction of the Ark subscribes to the Vitruvian principal of anthropomorphism. He has a plate showing exactly how the Ark reflected the proportion of the human body, which was later also to be incorporated into both the Tabernacle of Moses and Temple of Solomon. Most of those who have written on this subject before him visualized the Ark as a kind of ship, whereas in fact it was a floating container of which one third was under water. Kircher's search for accuracy also extended to such practical details as devising a workable method of sanitation for both the animals and the human beings enclosed in the Ark.

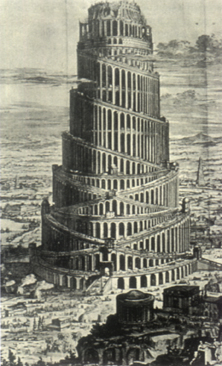

In The Ark of Noah, Kircher announced the forthcoming publication of his The Tower of Babel which appeared four years later: a complement of the former. Kircher's task in his second effort was rather more difficult. First, Kircher had much less to go on; the Biblical account of the Tower of Babel is condensed into a few verses. Secondly, this was a masonry structure and far more ambitious in undertaking than the building of the wooden Ark. Kircher rejected the prevailing theory that, when the Bible stated that Nimrod aimed to reach Heaven, in fact he meant the 'Celestial Empire'. This would have involved building a masonry structure whose height was five times the diameter of the Earth's sphere, which was absurd in his view. Kircher produced a diagram to show that this would have displaced the Earth's centre of gravity.

Kircher concluded that the Tower must have been circular in plan and helical in elevation. This form leant itself most easily to the transportation of the immense quantities of materials and supplies needed to keep the structure rising heavenward. He depicted the helix structure of the Tower as an arched construction, the overall effect being reminiscent of the attempted reconstruction of the Tower of Babel painted by Peter Bruegel (°ca1525-†1569).

One fundamental characteristic Kircher and Leibniz did share: the desire to reveal absolute truth through the sciences. Just as Kircher had hoped his universalis methodus might result in bringing peace to men, so Leibniz thought of his calculus as serving the same end. For Kircher it meant a return to a golden age prior to the Confusio of the Tower of Babel and the division of tongues, to a period illuminated by sages and patriarchs as Zoroaster, Abraham and Hermes Trismegistus. For Leibniz it implied opening the gates to a new Golden Age to which he believed that he possessed the key, the science of geometry. But for both of them it meant achieving something of the symbolic order and harmony implicit in the God-inspired architecture of Noah's Ark and the Temple of Jerusalem.

The Haiyuantang 海晏堂 (Calm Sea) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The Haiyuantang 海晏堂 (Calm Sea) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

Hudong Xianfa Hua 湖東線法畫 (The Oriental Side of the Lake).

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Hudong Xianfa Hua 湖東線法畫 (The Oriental Side of the Lake).

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

§3. LOCATING THE DISTANCE POINT: PERSPECTIVE AS REPRESENTATION OF SYMBOLIC ORDER

Perspective has been a continuing topic of intellectual inquiry since the Renaissance because of its operative stamina in understanding the Aristotelian conception of the world as God's art, and God's painting. Alberti first defined painting as concerned with the visible, and explicitly incorporated perspective as geometry of the visible. Leonardo held that the science of painting included studies of colours, surfaces, shapes and distances of things, and this "[…] science is the mother of perspective […]" which is related to Astronomy, thus placing it in the realm of Aristotle's 'physical' mathematics. 14 After Alberti and Leonardo, the development of constructing perspectives followed the Aristotelian definition of art as rational procedure, and had the effect of transforming the sciences of nature into the 'theory' of art. This Aristotelian view of the world as God's art continued its intellectual tradition until the new philosophy posted by Galileo.

Counter-Reformation thoughts continued the Aristotelian principles discerned by Aquinas and celebrated art as a paradigm for human thought. The idea of the universality of visual images, rooted in their address to sense, was essential to Counter-Reformation arguments concerning the rhetoric of images. The importance of images emulates Aristotelian principles: that all men desire to know, and that all human knowledge is derived through sense. Sense, in turn, comprehends what is present, and without such comprehension our faculty of knowledge is restricted. In particular, the Jesuits consider perspective images to be the most powerful means of instruction, the most universal and irresistible form, and not just for the illusion of Aristotelian psychology to painting, which have far-reaching implications for both pedagogy and propaganda. Perspective brings images to us as if present, and the address of these arts to sense promised not only the salvation of Christians by erasing the time between them and sacred stories, it also made these stories the potential history of all people in the world.

Cartesian philosophy in the late seventeenth century was gaining intellectual favour by calling for the necessity of demarcating 'clear and distinct' knowledge (which is one of the hallmarks of Cartesian philosophy) and by doing so it implied a counterpart: 'obscure and indistinct' knowledge as it might be called. This philosophical demarcation also marks out the original domain of the modern field of aesthetics: visual arts. However, the Cartesian view does not reject that Aristotle's "common sensible" were optical ad, therefore, mathematical. Leibniz considered the "[…] notions common to several senses, such as number, magnitude, shape and figure […]"15 to be inherently more distinct. In his Discourse on Metaphysics, Leibniz distinguished between distinct knowledge and obscure, confused, adequate and inadequate. 16 Distinctness thus presupposes analysis and definition. We know few things distinctly, and the terms we use to define what we know are themselves not adequate. Obscurity is nearly an optical quality, belonging to things we "[…] can not make out […]" and has a metaphorical dimension that we "[…] can not quite see […]".17 Perspective definitely provided optical science with a rational procedure of perception and conception by which knowledge is discerned.

The Huayuanmen 海晏堂 (Garden Gate) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The Huayuanmen 海晏堂 (Garden Gate) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The Xianfashan 線法山 (Perspective Hill) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

The Xianfashan 線法山 (Perspective Hill) pavilion.

ANONYMOUS.

Eighteenth century.

One of a Collection of Engravings depicting the Xiyanglou pavilions.

Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

During the seventeenth century, art, 'gardening', and architecture -disciplines responsible for the configuration of man's world - were necessarily concerned with the fundamental problem of philosophy; the reconciliation between subject and object.18 For celebrating the meaning of life, the arts confirmed human relations to the sphere of absolute values. The use of perspective was appropriate for an ideal organization of external reality. The transformation of perspectival cities, gardens, and internal spaces implicitly demonstrated the belief in the transcendent nature of geometrical knowledge. But Baroque perspective, in contrast to nineteenth century perspectivism, was a symbolic configuration, which allowed reality to relate to human perception in an essentially Aristotelian world, Perspective made it possible for seventeenth-century artists to transform the physical environment into a symbolic reality. In this way, it also embodied a symbolic operation, perceived through sensory experiences, evoking ideal truth. In seventeenth century Versailles, colour, smell, light, water games, fireworks, and indeed, the full richness of mythology played a major role in symbolic representation. Consequently, Castiglione's construction of the European section of Yuanmingyuan seed the Baroque science and art in the soil of China. With the 'luck' of historical coincidence, the Jesuits were able to foster Baroque development of architectural thinking, specifically the idea of disegno as the foundation of arts and graphic procedures of constructing linear perspective as Western architectural theory, and carried them to China as theological and scientific imports. After the seventeenth century, modern philosophy rejected the texts of Aristotle and modern science replaced the Book of Genesis with 'the book of nature' whose text became immutable geometrical figures and numbers.

§4. DISTANCE POINT IN CONFIGURATION: DEVELOPMENT OF JESUIT PERSPECTIVE IN ARCHITECTURE

Baroque culture was intimately bound to the Counter-Reformation and in particular, the Jesuit order which allied art with science and religion. For example, the concern with acoustics and optical effects in Jesuit sermons is reflected in the church plan of the Gesù in Rome, the first Jesuit church designed by the Jesuit priest Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (01507-†1573). Vignola established a lecture-hall-like geometry derived from a combination of the central plan (the grand scale of the dome) and the basilica plan (reduced, however, to a single nave, the side aisles replaced by chapels).

The facade of the Gesù was finished by Giacomo della Porta (01532-†1602) in 1575 and served as a prototype for many later Baroque churches, including St. Paul's (1602-1627) in Macao.

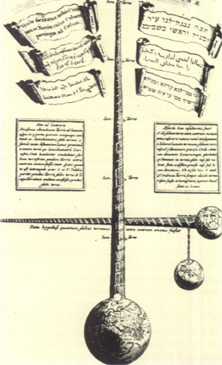

Athanasius Kircher, the interior organization of Noah's Ark.

In: KIRCHER, Athanasius, La Chine d'Athanase Kirchere.

De la Compagnie de Jesus, ilustrée De plusieurs Monuments tant Sacrés que Profanes, Et de quantité de la Nature et de l'Art […], Amstelodami, Johannem Jenssenium àWaesberge [...], 1670.

Athanasius Kircher, the interior organization of Noah's Ark.

In: KIRCHER, Athanasius, La Chine d'Athanase Kirchere.

De la Compagnie de Jesus, ilustrée De plusieurs Monuments tant Sacrés que Profanes, Et de quantité de la Nature et de l'Art […], Amstelodami, Johannem Jenssenium àWaesberge [...], 1670.

Not only had Vignola established a Jesuit model for the Baroque church using geometrical orderings, but he explicated "Jesuit perspective" in Le due regole della prospettiva practica (Rome, 1583) as the distance-point method of linear perspective, known in contemporary terms as the workshop method, or the office method which divides lines to obtain ratios between them without defining precise locations of vanishing points. This technique could be manipulated to produce a unified central perspective without designating the picture frame favoured by Alberti's techniques of vanishing-point perspective. The distance-point method was particularly "[…] favoured in the artist's workshop of northern Europe and proved effective in construing a cartographic vision of the world […]" for the Age of Discovery. 19

Through the science of perspective, the Je-suits were able to unite Christianity with art and science, such as in astronomy and architecture, by ordering nature and supernature in geometrical relationship and representing terrestrial space and celestial space in pictorial space. Linear perspective was applied to a unique way of thinking that took in the entire universe from the infinite to the infinitesimal; it was a crucial constituent of total knowledge. For the Jesuits, it was significant to discover that the Divine infinity could be represented in pictorial, finite space without defining a vanishing point, as well as designating a picture frame. Hence, trompe l'oeil became a technique associated with Jesuit perspective to allude to flight, movement, instability, metamorphosis, magnificence, and paradise.

In La perspective pratique par un Parisien, religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus (3 vols., Paris, 1642-1649), Jean Dubreuil started a Jesuit ecclesiastic function to direct the world through perspective order. With Dubreuil "[…] every natural and architectural phenomenon that can be reduced to perspective is so reduced and every form of unconcealed change is submitted to the general discipline of perspective […]."20

Moroever, the good "religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus" was concerned with the application of perspective decoration to every aspect of his life, as well as to the theatre, the representation of life. Evidently, the care with which Sebastiano Serlio worked out the vanishing points of his perspective had little to do with Vitruvius and more to do with the maturation of the Baroque perspective; stage, but he certainly opened the domain for Jesuits to contribute their ecclesiastic illusions to the theatrical representation of space.

A self-proclaimed "lover of perspective", Andrea Pozzo (01642-†1709) epitomized Jesuit ecclesiastic illusions as 'theatres' or the world with scientific conviction in religion and his dizzying trompe l'oeil. In the Preface of his Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum treatises, Pozzo firmly announced that he intended "[…] with a Resolution to draw all the lines thereof to that true point, the Glory of God." In the engravings of both his real and ephemeral architecture, illusion was miraculously to coalesce the distorted chaos of shapes into a coherent revelation when viewed from the proper position.

The Deluge - depicting Noah's Arch on the background.

In: KIRCHER, Athanasius, La Chine d'Athanase Kirchere.

De la Compagnie de Jesus, ilustrée De plusieurs Monuments, tant Sacrés que Profanes, Et de quantité de la Nature et de l'Art […], Amstelodami, Johannem Jenssenium à Waesberge […], 1670.

In Pozzo's proposal for theatre design, the point of infinity in stage scenery, alluded to by angels flats, mirrored the privileged location of the royal box where the single-point-viewing perspective incarnated the epiphany of the ideal;. In the case of the nave vault of St. Ignazio, in Rome, "The Glory of St. Ignatius" (1688-1694), the perspective point is actually the Son of God, who in Pozzo's own words "[…] send[s] forth a ray of light into the heart of Ignatius, which is then transmitted by him to the most distant regions of the four parts of the world."21 As a virtuoso of trompe l'oeil and of that famous Italian perspective known as di sotto in su (from below up-wards), Pozzo brought Paradise down to within sixty feet of the Earth ad majorem dei gloriam (To the Greater Glory of God), the motto of the Society of Jesus. As it surged to its central focus, the perspectives system of optical dynamics served as the radiantly core of vision while the rays of spiritual energy radiated to people of the world through Jesuit missionaries.

§5. THE DISTANCE POINT IN TRANSLATION: JESUIT PERSPECTIVE IN CHINA

Matteo Ricci was the first to realize that in order to spread the Christian faith, enlarge his audience, and above all, convert the high officials (the Chinese literati), it was advisable to present himself as a radiant ambassador of Western science rather than as a humble missionary who had taken the vow of poverty. 22 With such apparent purposes, Ricci brought two important books to China: the aforementioned Evangelicae historiae imagines […] by Hieronymus Nadal and the annotated and illustrated copy of Euclid's Elements of Geometry by Jesuit mathematician Cristoforo Clavio (01537-†1612). 23

Like all missionary orders in the sixteenth century, the Jesuits were concerned that their converts might misinterpret Christian images and worship them just as they had worshipped their idols. Ricci's intention, therefore, was to employ drawings and paintings as a liturgical means of conveying Christian messages, especially to those literati unable to understand verbal expression of divine meaning. Ricci's aims were to convince the Chinese through the perspectival 'realism' of drawings in Nadal's book that Christ is indeed the 'living' God and to provide the converts with 'given' images to imagine and obtain the liturgical meaning for God. 24

Unfortunately, Ricci was incompetent to demonstrate Renaissance perspective and chiaroscuro, as well as unable to present the discovery of disegno from the recently founded academies of Florence and Bologna.

After completing his novitiate at the Jesuit monastery at Coimbra, Giuseppe Castiglione sailed on a Portuguese ship, tracing Matteo Ricci's footsepts, and arrived in Macao in July 1715, Kangxi· year 54, Four months later, Castiglione was presented to the emperor under the aegis of Fr. Matteo Ripa (01682-†1745)25 working alongside Chinese painters and given the Chinese name of Lang Shihning. · Employed in the Court, Castiglione secured a privileged position to incorporate techniques of perspective and chiaroscuro into Chinese painting.

Athanasius Kircher, the Tower of Babel.

In: KIRCHER, Athanasius, Turris Babel, Amstelodami, Johannem Jenssenium à Waesberge […], 1679.

No other Jesuit in China could articulate the Western science of art as effectively as Castiglione, a disciple of Andrea Pozzo. Before Castiglione's presence in Court, no other Chinese painter employed the chiaroscuro method in painting, nor did they attempt to present any perspectival effects typical of the Renaissance perspective. In Qianlong'· s Court, Castiglione's artistic performance was more of an illustrator than an artist. His talent and knowledge of painting was directed to document historical events such as battles in Upper Asia, Kashgaria, Turkestan and Zungaria, and the Emperor's ceremonies such as the famous "Mulan"· scrolls (each: 27.00 x -0.77 metres) recording the Emperor's annual hunting event. Castiglione was effective in articulating sophisticated techniques of perspective. Through deciphering Pozzo's treatises, Castiglione confronted the Chinese conception of painting and picture by integrating the science of art with his religious understanding of disegno.

During Yongzheng's· reign Castiglione assisted Nian Xiyao, · Superintendent of Customs and Director of the Porcelain Works in Jingdezhen, · to adapt Andrea Pozzo's treatises Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum into Chinese with the title Shixue (Visual Techniques), which appeared in 1729 and was reissued in 1735. In his Preface to Shixue, Nian Xiyao stated that he studied the subtleties of Chinese painting, especially the illusion of three dimensions by shadows under the guidance of the Western master Lang Shihning, i. e., Castiglione.27 The term linear perspective was first regarded as a special kind of visualization; its Chinese translation, xianfa, · did not denote any perspectival effects. 'Xianfa' literally means 'linear method' and relates more to the idea of disegno than linear perspective.

One of the many differences between Chinese and European ideas of paintings lies in the fundamental understanding of 'line' and its functions in representation. Although the techniques of Chinese literati painting are" based primarily on lines, this linear technique is integrated with calligraphy within whose lines are essential forms of pictorial representation. Both Chinese literati painting and calligraphy elaborate on the 'strength' of brush work and its variations of line-forms. To the Chinese, permeated by Daoist teaching, the term 'still-life' has no meaning. There are no inanimate objects (including lines); everything has its vitality and spirit. Chinese painting tends to manifest the possibility of depicting the expression, rather than representation, of being. The Chinese postulate the impossibility of addressing permanent being through impermanent becoming. The function of lines in Chinese paintings do not illustrate the same conceptual representation as they do in Renaissance realism or Baroque naturalism. In contrast, by appropriating line as a conceptual apparatus, the development of disegno had provided Renaissance perspective and chiaroscuro with a scientific foundation to distinguish line as an irreducible element of geometrical construction from an essential form of pictorial, graphic presentation. The Western painter, armed with the sciences of mathematics and physics, followed linear perspective, observed chiaroscuro, and sought to draw buildings in accordance with architectonics and strove for anatomic accuracy in portraying human figures.

Athanasius Kircher, displacement of the earth's centre of gravity by the Tower of Babel.

In: KIRCHER, Athanasius, Turris Babel, Amstelodami, Johannem Jenssenium à Waesberge […], 1679.

The Xingting 行亭(Garden Gate) pavilion.

Present-day restored condition.

Photograph taken in 1995.

As an architect, Castiglione was an effective agent of Baroque architecture in the construction of the European section of the Xiyanglou, ·which took place from 1747 to 1760. The European palaces at the Yuanmingyuan were begun in 1747 after drawings by Castiglione, whose knowledge of perspective geometry served as the foundation for positioning allegorical figures and devices in/of/among buildings to obtain every possible perspectival effect: a design process followed his graphic procedures of constructing linear perspective.28 The site plan of this European garden appropriated a central axis by which routes and passages were organized to emphasize a series of perspective spectacles. Remarkably, the eastern section of the garden was faithfully grouped for constructing the scenery of the Baroque perspective stage. From Xianfashanmen· (Perspective Gate) to Xianfashan· (Perspective Hill), the linear progression of perspective views finally led to a long rectangular Xianfahu· (Perspective Lake). The Emperor could sit at the western end of the lake and enjoy as European street presented by a Baroque stage at the eastern end.

The final building designs submitted to the emperor by Castiglione were a fascinating kind of Baroque. As far as one may judge from the ruins and the decorative fragments which still may be seen at the XiyanIou and in some Beijing parks and gardens, Castiglione might have drawn his main inspiration from Baroque Italian architecture. "Some of the curving façades with their curving lines and their enormous volutes over the doorways and windows remind one of Borrominesque buildings, other of Genovese palaces from the late sixteeenth century."29 "The French influence is, on the whole less apparent […]"30 in building design, but evident in reference to Versailles for the European sources of landscape.

"A place is created by natural spirits and treasured by Heaven which provides a space for [the] King to wander and rest […],"31 according to comments from the Qianlong emperor when surmising the extreme beauty of the XingyanIou after its construction. Evidently everything in these buildings demonstrated a deep admiration for theatrical spectacles: architectural motifs stimulating abounding of all senses, a Baroque profusion of superfluous ornaments. However, composite it was, the total effect of Chinese Baroque was nonetheless elegant. It was impossible, said the Jesuits, not to "[…] admire the art with which this irregularity was carried out […]."32

On the 5th of August 1774, news reached China of the arrest and imprisonment of the General of the Jesuits, Fr. Laurent de Ricci, and the papal proclamation of the dissolution of the Society of Jesus. Foreign missionaries were never to regain the privileged positions the Jesuits had formerly enjoyed at the Imperial Court. In the following century the Europeans employed very different methods to impose their will; the cannon took the place of the sermon. When the Franco-British troops led by Lord Elgin and General Cousin-Montauban pillaged Castigione's Summer Palaces in 1869, the 'Arabian Nights' places of the emperors of China and their curious toys, monkeys, automata-dancers, cymbalplaying rabbits, went up in flames. Even the memories of buildings dedicated to the refinements of pleasure has vanished. The only existing witness to this magnificence are twenty copper-plates made in 1786, by two pupils of Castiglione under the supervision of the Emperor.

The Xingting 行亭(Garden Gate) pavilion.

Corner detail showing the engaged Tuscan columns and the Chinese style projecting eaves.

Photograph taken in 1995.

CONCLUSION

For nearly two-hundred years, from 1582 to 1773, the Jesuits had a privileged position in the Middle Flowery Kingdom, enabling them to act as cultural interpreters between East and West. Their presence in China mirrored the unique period of enlightened intellectual inquiry in the West, as the Age of Reason flourished throughout in Europe. 'Jesuit Perspective' was developed for obtaining the epiphany of symbolic images, thoughts and places while it was cultivated by the Faith to reveal absolute knowledge through sense. When "Jesuit Perspective" was practised as an architectural theory to establish the geometric order of the world, the Jesuits confronted the Chinese with a unique, perspectival view of the world. In China, "Jesuit Perspective" has consequently rationalized and democratized the visible realms of technology and science, which were once an important contrast and a significant connection between East and West. The differences reflected the anthropocentric view of architectural thinking and its practises in the West. More importantly, the West recognizes the construction of drawings of an epistemological process to depict the conceptual in the domain of the perceptual and, consequently, to transform the invisible into the realm of the visible.

NOTES

1 POZZO, Andrea, Perspective in Architecture and Painting: An unabridge reprint of the English-and-Latin edition of the 1693 "Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum", New York, Dover, 1989.

2 NICOLAS, Antonio T. de, Ignatius de Loyola: Power of Imagining, S. J. Albany, State University of New York, 1986, p. 116 - For a hermeneutic of St. Ignatius of Loyola using a new translation of his Spiritual Exercises, his Spiritual Diary, his Autobiography and some of his letters.

3 CALVINO, Italo, Six Memos for the Next Millennium, Cambridge/Massachussets, Harvard University Press, 1988, p.86.

4 SPENCE, Jonathan, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, New York, Penguin Books, 1984, pp.62-63 - For a discussion of Ricci's use of Nadal's book and his construction of the "memory theatre" in China.

5 TAYLOR, René, Hermetism and Mystical Architecture in the Society of Jesus, in WITTKOWER, Rudolf-JAFFE, Irma B., eds., "Baroque Art: The Jesuit Contribution", New York, New York University Press, 1972, pp.63-97; YATES, Frances, The Art of Memory, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1966, pp.82-104.

6 LACH, Donald F., The Preface of Leibniz' Novissima Sinica, Honolulu, University of Hawaii Press, 1957 -The author suggests that the 1699 edition, a revision of the 1697 text, was published in Leipzig. Neither edition gives the name of a publisher nor the place of publication.

The Novissima Sinica is the only book Leibniz (01614-†1716) ever published on a subject which was of consuming interest to him from about 1689 until his death twenty-seven years later. Only the Preface of the Novissima Sinica may be attributed to Leibniz's pen. The remainder of the book is a diverse collection of materials, primarily by Jesuits in China, which came into his hands by diverse routes. The Preface was first translated by Donald F. Lach. His translation was slightly revised and collected by Daniel J. Cook and Henry Rosemont's mentioned work.

See: COOK, Daniel J. - ROSEMONT, Henry Jr., trans., Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Writings on China, Chicago, Open Court Publishing Company, 1994, p.46 - The authors' emphasis is in bold print.

7 Ibidem., p.50 - Authors' emphasis in bold.

8 LOEMKER, L. E., ed. and trans., Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Philosophical Papers and Letters, 2 vols., Chicago, 1956 - From where the mentioned works were extracted.

In his Studies in a Geometry of Situation, Leibniz proposed a science of extension to integrate Geometry and Algebra.

9 COOK, Daniel J. - ROSEMONT, Henry Jr., trans., op. cit., p.11 - Where the authors discuss the connection between Leibniz and Kircher.

10 KIRCHER, Athanasius, TUYL, Charles D. van, China monumentis qua sacra qua profana ilustra, Muskogee, Indian University Press, 1987.

11 TAYLOR, René, op. cit., pp.63-89.

12 Kircher refers to his previous publication Œdipus Ægyptiacus (Rome, 1652).

13 KIRCHER, Athanasius, 1987, op. cit., p.214.

14 SUMMERS, David, The Judgment of Sense: Renais sance Naturalism and the Rise of Aesthetics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987, pp.137-138.

15 Ibidem., p.184.

16 LOEMKER, L. E., ed. and trans., op. cit.

17 SUMMERS, David, op. cit., p. 182.

18 PÉREZ-GÓMEZ, Alberto, Architecture and the Crisis of Modern Science, Cambridge/Massachusetts, MIT Press, 1983, pp. 165-201 - Chapter Perspective, Gardening and Architectural Education.

19 ALPERS, Svetlana, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1983, pp.26-71.

20 LAWRENSON, T. E., The French Stage and Playhouse in the XVIIIth Century: A Study in the Advent of the Italian Order, New York, AMS Press, 1986, p.178; KEMP, Martin, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat, Yale/New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990, p. 122.

21 Ibidem., p.139

22 SPENCE, Jonathan, op. cit. - For a discussion on the early Jesuit mission in China.

23 Cristoforo Clavios was an eminent mathematician at the Collegio della Propaganda Fide, in Rome, Who was asked to validate Galileo's claims. Clavios was the first to accept the telescope as a scientific instrument and stressed that its revelations could no longer be ignored. The course of the struggle between geocentric and heliocentric cosmologies was changed irrevocably by the telescope. Clavios analyzed and translated Euclid's Elements into Latin in 1574. He also reformed the calendar named in honour of Pope Gregorius XIII which went into effect in Europe in 1582.

24 VANDERSTAPPEN, Harrie, S. V. D., Chinese Art and the Jesuits in Peking, in RONAN, Charles E., S. J. - OH, Bonnie, B. C., eds., "East Meets West: The Jesuits in China, 1582-1773", Chicago, Loyola University Press, 1988, pp. 103-126, p. 122 - "They used art to illustrate Christian doctrine, and whatever artistic merit these illustrations had was, in the eyes of the Chinese, easily overshadowed by the strange and new technical qualities they saw. That seems borne out by the emphasis in Chinese reactions to the use of perspective and to modeling in light and dark combined with lifelikeness, and by the fascination they developed for cartography, topography and maps, and, finally, the measurement of distance and time in astronomy, clock work, time pieces, and configurations of the calendar."

25 Matteo Ripa, an Italian Jesuit who arrived in China in 1708 and was at the Court of the Kangxi Emperor, was sent to the emperor's Summer Palace and gardens at Jehol to execute thirty six engravings of the imperial estate. In 1713, his authentic record of the huge and lavish imperial gardens must have arrived at the most opportune moment in Europe for 'Chinese style'. Returning to Naples, he founded a college for Chinese in 1732.

See: CONNER, Patrick, Oriental Architecture in the West, London, Thames and Hudson, 1979.

It was common for Jesuits to be employed by the Imperial Court. By 1743 there were twenty-two Jesuits in Beijing: ten French and twelve Portuguese, Italians and Germans. Seven of these twenty-two Jesuits were employed exclusively in the service of the emperor and the rest of the were associated with the Court's activities.

Also see: BEURDELEY, Cécile - BEURDELEY, Michel, Giuseppe Castiglione: A Jesuit Painter at the Court of the Chinese Emperors, Rutland, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1971.

26 Ibidem., p.152 - The authors quoting Archbishop Lo Kuang on the occasion of the exhibition of Castiglione's paintings: "The horses and the flowers painted by Giuseppe Castiglione are exactly what they are in reality; it is a photograph and that is all; there is neither the spirit nor the rhythm of Chinese painting […]. If he studied Chinese painting it was to facilitate the propagation of his religion and that is praiseworthy.. Although he remained in Peking [Beijing] for fifty years, he never learned to write Chinese. That is why the images of the saints which he painted for the churches of Peking and its suburbs are not signed by him. The signatures they bear in Chinese characters are not by his hand. His painting has not influenced Chinese painting."

27 The text reads "Lang Si-ning" rather than "Shih-ning". It might be Nien's mistake in pronunciation.

28 ADAM, Maurice, Yuen Ming Yuen: L'oeuvre Architecturale des Anciens Jésuites au XVIIIème Siècle, Pei-ping, Imprimerie des Lazaristes, 1936, pp.23-40.

29 SIRÉN, Osvald, The Imperial Palaces of Pekin, New York, AMS Press, 1976, p.47 [1st edition: Paris, G. van Oest, 1926].

30 LOHER, George Robert, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766): Pittore di Corte di Ch'ien-lung, Imperatore della Cina, Roma, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1940, p.86.

31 Collected works of Giuseppe Castiglione, Taipei, National Palace Museum, 1983, p. 12.

32 BEURDELEY, Cécile - BEURDELEY, Michel, op. cit., p.74.

* Researcher on the Architectural Manifestation of Historical Consciousness and in techné in the Art of Making. Ph. D. in Architecture from the Institute of Technology, Georgia. Lecturer in the Department of Architecture at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science. The essay presented in this edition is part of his current interest in the Cultural Invention of Baroque.

start p. 155

end p.