A pair of shallow saucers decorated with 'painted' enamel outdoor scenes depicting European protagonists.

Qianlong period.

A pair of shallow saucers decorated with 'painted' enamel outdoor scenes depicting European protagonists.

Qianlong period.  11.9 cm.

In: porcelana Chinesa de Exportaçã: Diálogo entre Dois Mundos [Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado, 1992, ill. no96.

11.9 cm.

In: porcelana Chinesa de Exportaçã: Diálogo entre Dois Mundos [Catalogue], Macau, Leal Senado, 1992, ill. no96.

Amongst the millions of objects which represent the art production efforts of the of the hard-working Chinese people — which had already reached a high degree of aesthetic culture in archaic times — are rare multiple objects of different shapes and obviously intended for varied purposes, which the less discerning would immediately classify as porcelain wares. The difference, however is obvious even to the less discerning connoisseurs.

These objects, whose bodies are in fact made of metal, expose surfaces covered by a smooth and diaphanous vitreous substance, a compound of silica, minium and potassium to which were added, during fusion, metalic oxides as colouring agents. These objects are generically named 'enamels'.

A number of researchers agree that the vocable ‘smaltum’ was first employed by an anonymous author in a biography of Lion IV (°847-†855), who vanquished the Sarracens at the mouth of the Tiber river and founded the city of Lion, nowadays called the Vatican. This word appears again in the following century, more rigorously contextualized in the Diversarum Artium Schedula, a practical treatise of coeval industrial arts written by the artist monk Theophilus. The author describes the procedures used those days by the Byzantine enamel workshops, those techniques being so identical to the Chinese that it remains speculative as to the existence of a unique source for both the geographically remote Western Byzantine and Eastern Chinese enamel artistries.

It has been nonetheless ascertained that Byzantium was not the cradle of the art of enamels because specimens have been found in major trading nucleus of Occidental Asia, which antedate the foundation of the city. Apparently, even in these remote times, the popularity of enamels was considerable, influencing a number of Celtic masterworks found in Ireland ascribed to the dawn of Christianity on those distant shores.

Although there are samples of enamels produced in Byzantium as early as the times of Justinian, the industry of enamels was only consistently developed in the city as a local technique after the fall of the West Roman Empire reaching the summit of its craftsmanship during the Middle Ages.

It was only during the fourteenth century that the Byzantine enamels started to be consistently exported beyond the borders of the Empire.

It is quite possible that the first enamel objects reached China through its northern regions, being brought in the loot of Chengji Sihan·(Ghengis Kahn) hordes returning from their westernmost incursions through the Asian continent. But it is also probable that Armenian and Persian merchants introduced enamel objects into China as high value art items traded in exchange for native products of the Middle Kingdom.

One way or another, it as been convincingly proved that Arabian merchants traded enamel objects in Guangzhou, the native name for these wares being dashichan· (Arabian wares).

It seems that the systematic manufacture of enamels only started being developed in China during the fourteenth century. Chinese researchers point out that only the second edition of the famous Gegu Yaolun· dating from 1459 includes a section dedicated to dashichan, the first edition of the treatise, published in 1387, making no reference to enamels.

It is interesting to note that at a later date enamels became generically known in China as falangyao· (French wares). Based on the analysis of the etymon of the word several hypothesis have been put forward about the origins of these objects and their manufacturing techniques, a possible interpretation of the vocable justifying eventual foreign sources.

Some scholars support the thesis that ‘falang’ is a Chinese adaptation of the Western word ‘Franci’ — a word used in dynastic China in reference to Christian related matters first used in the southern provinces of the Empire, and ultimately derived from the name of the country ‘France’. Other sinologists, such as Hirth, state that the word has association with Bethlehem, the birth-place of the Holy Saviour. Bushell, one of the greatest authorities on Chinese Art states in his book Chinese Pottery and Porcelains that ‘folin’ or ‘fulin’ (according to the Beijing pronunciation) first appeared as a Chinese term during the fist decade of the seventh century alternatively meaning Dashin, · the traditional name given in China to the capital of the Holy Roman Empire of the East.

He argues that the term- 'folin' corresponds to the name Polin, the toponymic appelation of Constantinople during the Middle Ages.

The curious book by Rockhill, The Journals of Friar William Rubruk, describes a meeting in Karakorum, Mongolia, between the monk and the French jeweller and silversmith Guillaume Boucher, who might have been the first artist to produce enamels at the Mongol court. Those days, Karakorum was a thriving metropolis and the meeting point of delegates from foreign potentates, Catholic and Nestorian missionaries, merchants of all sorts and intrepid Europen adventurers. Most writers of Chinese art follow the idea that in fact, ‘falang’ is just an oral corruption of the name ‘Guillaume’.

We find it difficult to accept such a hypothesis due to the disparity between the two sounds, unless ‘falang’ was the Chinese name given to Guillaume Boucher in the Middle Kingdom, similarly to what happened with the Jesuits, such as Matteo Ricci who became known as Li Madou· or Ferdinand Verbiest as Nan Huairen. Ìt must be noted that ‘falang’ is written with the radical 王 which is an abbreviation of the word yu· (jade), which confirms the word being related to a substance and not to a place [or name].

There is a passage in the Taoshuo· published in 1774, that states that the "dashishan"· are similar to the objects manufactured in "Falang". This statement seems to conclusively resolve the arguments about the Chinese origins of the term ‘enamel’ in favour of those who associate it with the early city of Polin, later Byzantium, then Constantinople, and nowadays Istanbul.

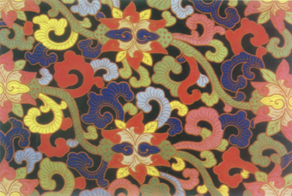

Flagpole pedestal decorated with mixed cloisonné and plique-à-jour enamels — detail.

The metal surface of the plique-à-jour work overpainted black.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 17.

Flagpole pedestal decorated with mixed cloisonné and plique-à-jour enamels — detail.

The metal surface of the plique-à-jour work overpainted black.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 17.

Enamels are not highly regarded by the Chinese in general. Not only are they detrimentally considered as the result of a foreign imported technique but also their matt luster and the uneveness of their surface are considered coarse and not a match for the translucent shine and the homogeneity of porcelain. The reference that the Gegu Yaolun makes to enamel jars, urns, caskets and bowls is far from being enthusiastic, saying that their flamboyant colourings hardly arouse the interest of literati, being more appropriate to adorn the ladies' quarters.

Enamels can be either transparent or opaque. The first can be obtained by melting all the component ingredients at an even temperature, while the second ais obtained by adding a mixture of tin and calcinated lead to the original component ingredients.

They are usually categorised as champlevé, cloisonné, basse taille, plique-à-jour or simply 'painted', according to their different manufacturing procedures.

The champlevé technique or layered enamel technique is made by chiselling deep incisions on a metal ground in such a way that the contours of the desired patterns to be filled with the enamel paste are defined by the rising edges of metal. Molten enamel is then poured into those cavities, the shapes of the final pattern being the defined by their raised metal contours.

The cloisonné technique of incrusted enamel technique diverges from the champlevé on the structuring of the coloured compartments or cloisons — in French — which are defined by filiform partitions of metal welded to a continuous metal sheet. These filiform partitions are usually numerous allowing fora multiplicity of small scale complex pattern fields which, in the intial manufacturing stage, are filled with multicoloured powders. After all the receptacles are filled with powder the whole object is fired several times until the glaze reaches an optimal result. After cooling, the entire surface of the object is then finely polished with a mixture of ground pumice an charcoal. A final touch is given by firing gold leaf to the exposed edges of the metal filiform partitions.

In the taille basse technique the pattern is incrusted in low relief in the metal surface which constitutes the overall shape of the object. Molten enamel is then poured into the excavated patterns, the final result being a continuous leveled surface of dried molten enamel and that of the original metal sheet.

The plique-à-jour technique or translucent cloisonné technique is in every way the same as the already described cloisonné technique the only difference being that the ground metal support surface is detached immediately after the cooling of the enamel, fully exposing the true colourings of the enameled partitions of the object's body.

The 'painted" technique consits in consistently pouring the coloured enamels over the entire surface of the metal ground.

The Chinese only adopted two methods of manufacturing enamels: the cloisonné and the 'painted'.

The first known enamels produced in China were all produced in the cloisonné technique and date from the Yuan· dynasty (1280-1368). Extremely few examples of this period have survived to the present.

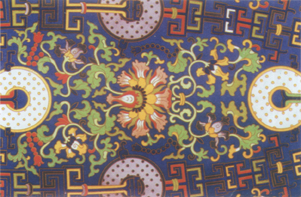

Jar decorated with cloisonné enamel patterns — detail.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 36.

Jar decorated with cloisonné enamel patterns — detail.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 36.

The peak of enamel production and artistry in China was during the reign of the Jingtai· emperor (r. 1450-† 1457), of the Ming· dynasty. Numerous objects bearing the reign mark of this emperor have survived to the present. These pieces coincide with the fall of Contantinople to the Ottoman Turks, in 1453, which oresulted in an extraordinary influx of Western immigrants into the Chinese empire. This might be the reason why enamels are still known by certain traders as ‘jingtailan’·— bearing in mind that ‘lan’, and not ‘lóng’, is the correct character in this case.

The enamel objects from this period are boldly innovative in the overall configuration of their compositions, and unrivalled for the outstandingly patient and rigorous minutiae of its patterns, remarkable for the depth and purity of their colourings.

For instance, there is not one blue but two tones of blue: a darker deeper but extremely vibrant blue, and a celestial azure with a subtly tenuous greenish pigmentation. The vermillion is punicaceous; the yellow, extremely pure; the green, applied with extreme moderation; the rouge d’or merely circumstantial. Black and white colour patterns were suppressed due to the impossibility of successfully achieving the shine and the depth of the former and the immaculateness of its radiant brightness (which in most examples is adulterated and frosted).

Despite the best examples of this period being stunningly visual in the harmoniously distributed variety of tonal colourings and impressive in the overall careful distribution of their decorative elements, at closer inspection they reveal hair-like craquelures and countless tiny air pockets derived from the heteregeneous distribution of the enamels and by deficient heating and melting techniques.

Although not the most artistically pleasing, the most technically achieved enamels date from the periods of extreme production of the reigns of Kangxi, · Yongzheng· and Qianlong, · conspicuously surpassing those of the Ming.

Despite the repetitiveness of their shapes, the best enamels dating from the Kangxi period (r. 1662-† 1722) are remarkable for their audacious conception, and their excellent chromatic range. Their decoration is more sparse and more original.

The best enamels dating from the Yongzheng period (r. 1723-†1755) are quasi-identical to those of the previous period.

The best enamels dating from the Kin-Lông period (r. 1736-† 1795) acheived technical perfection. Their patterns were scrupulously selected deliberately matching the integral design of the decorations which, in turn, reveal having been conceived in rigorous synchronism with the shapes and proportions of the objects, the overall vision of these exquisite works of art expressing their masterful englobing conception. The manufacturers of this period managed to overcome the firing technical problems unresolved during the Ming dynasty, and if the shine and brightness of the colours of the enamels remained unsurpassable, the novelty of applied bronze mounts luxuruously gilt is their major outstanding characteristic. The lavishness of the multilayered gold-leaf appliques has been unrivaled by modern replicas which use electrical rather than direct firing procedures for gilding.

Vase decorated with ‘painted’ enamel patterns over a copper ground — detail.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 59.

But, ultimately and regardless of the technical achievements which enabled metalic moulds to become increasingly thin, enamels never managed to capture the voluptuous touch and sonority of the most perfect porcelains. Deprived of this extreme refinement and conscious of the foreign connotations related to the origins of this art technique, the neophobic spirit of the Chinese always prejudiced against imported tastes, maintained from the very start an in-built rejection to enamelled objects.

The splendid munificence of these three emperors of the Qing dynasty included an incessant foundation of new temples and monasteries which sumptuous furnishings required a continuous production of lavish objects. This increasing demand for cult objects gave rise to a developing manufacture of enamel objects. The production of enamels was particularly refined during the Qianlong reign when it became costumary to cast by imperial command, hieratic distichs of copper, silver and gold grounds.

This was a flourishing period when masterpieces of exceedingly perfect craftsmanship and highly aesthetic compositions by talented regional artists gave full vent to the excesses of the times and competed to leave to posterity innumerous works of art. Dishes, goblets, vases, plates, saucers, plaques with laudatory sayings — richly framed and resting on intricately carved stands made of previous woods — perfume bottles and all possibly imaginable objects were produced in enamel.

However, when the imperial patronage declined, the excitment for the import of enamels from surrounding tributary countries slackened and so the enthusiasm for the production of this art, gradually but inexorably, abated. By 1795, the last year of the Qianlong reign, with commissions being extremely few and far apart, the production of enamels in China reached an alltime low of difficult recovery. Devoid of incentives, enamel artists lacked the inspiration and the drive to manufacture objects expressive of their truly creative capacities.

By the end of the eighteenth century, on the antipodes of the world, in Limoges, a town in southeast France, French jewellers had discovered a revolutionary method which no longer required the filiform metalic compartmentalisation of receptacles, until then a necessary requirement of enameling. The novel procedure consisted on spreading a uniform layer of vitreous glaze directly over the metal support ground, firing it, painting any required pattern over this glazed surface, spreading over it a new uniform layer of transparent enamel and finally firing the lot at a temperature that would solidify the outer surface without damaging the underlayers.

Léonard Limousin became the supreme master of a remarkable pleiad of enamel artists which placed Limoges in the map of sixteenth century world cultural centres. With the arrival of the Jesuits in China, objects produced in this novel technique were to be rapidly copied by Chinese enamel manufacturers. The first objects made in China this technique date from the reign of Yongzheng (r. 1723-†1755).

'Painted' enamels became known in China as 'yangci'· (foreign porcelain), a name obviously derived from their imported origins.

The connoisseurs of Chinese enamels subdivide the ‘yangci’ into two different categories: those manufactures at the Zaobanchu, · at the Imperial Palace, in Beijing, and those produced in the province of Guangdong.

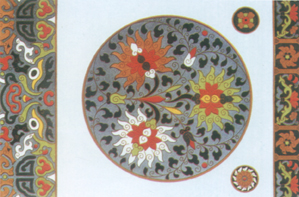

Details of several cloisonné enamel patterns.

In: JONES, Owen, The Grammar of Chinese Ornament [...], London. Studio Editions, 1987, ill. no 61.

The very first ‘yangci’ usually depict European life scenes in environments with protagonists dressed in the European fashions of the time or straightforward Chinese themes. The quality of most Guangdongnese production, made commercially and mainly for export purposes, is remarkly inferior to the finely crafted and relatively few pieces specifically made for the Court.

The Jesuits became expert artists in the production of these types of enamels depicting European themes. Chinese followers copied the Western religious' originals blending degenerated European figures with Chinese faces with a plethora of dissonant scenarios.

During the reign of the French king Louis XIV, his prime-minister cardinal Mazarin created a royal trading company called ‘Compagnie de la Chine’. This company was in charge of ordering the manufacture, in China, of large tableware porcelain sets bearing the royal coat-of-arms of the French king for the supply of the French Crown.

These porcelains were made at the kilns of Jingdezhen· and taken overland to Guangzhou where they were painted and finally glazed before being shipped to France. Many of these tableware porcelain sets had matching pieces of enamel, such as sugar bowls, teapots, etc.

This first royal order spread in Europe a craze for such tableware. Numerous orders from many European countries ensued, prescribing an obligatory depiction of the coat-of arms of the destined commissioner, either on the the rim or on the central partition of the porcelain pieces. Many enamels with matching coats-of-arms and same period decoration confirm that they were specifically made to be included in such sets; also determining their date of production, origin, and the mass-produced sophistication of manufactured artistry of contemporary southern China.

However, this was no more than a temporary fashion, the lusciousness of the ‘painted’ enamels merely fulfilling foreign demand without creating an impact on the tastes and the ingrained psychological parti-pris of the Chinese diletanti.

In fact, as soon as the European market was satiated by this trend the ‘erudite’ production of artistic enamels was discontinued, the overwhelming majority of the enamels manufactured during the last century exclusively aiming at a commercially orientated market endlessly churning trivial patterns destined to be sold to undiscerning ‘tourists’ eager to acquire not a cheap but unquestionably ‘typical’ Chinese souvenir.

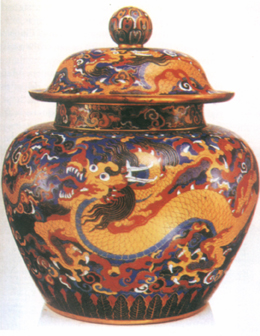

Cloisonné jar.

Ming Dynasty.

In: GOEPPER, Roger, La Chine Ancienne, [Paris], Bordas, 1988 p.363.

* Historian and researcher on the History of Macao. Author of numerous articles and publications on related topics. Sinologist.

start p. 149

end p.