§1. INTRODUCTION

Perhaps the most characteristic aspect of the Jesuit presence in China in the seventeenth century is in its relationship to the Imperial Calendar and to the Astronomical Bureau. This is particularly the case since the establishment, in 1629, of a Liju (Calendrical Bureau), for the introduction of contemporary Western calendrical lore, with the inclusion of all its mathematical and mechanical auxiliary sciences. This led, in 1644, to the acceptance of the xifa (Western rule), as the only one authorized, thanks to Johannes Adam Schall von Bell, S. J., who became the first regular Director of the Astronomical Bureau, in Beijng. It was he who, in 1660, invited Ferdinand Verbiest, then thirty seven years old, to Beijing, to become instructed in the various aspects of the Directorship and to eventually succeed him. Schall's main motive for this choice may have been a certain reputation of Verbiest of being a good mathematician, thanks to much private study, deepened during his professorship in Mathematics at the Jesuit Colégio das Artes, in Coimbra. Also, it is possible that a certain predilection of A. Schall for fellow fathers from German speaking or culturally related countries may have been the decisive factor in his choice. 1

Instrument made under the supervision of Ferdinand Verbiest, in 1669.

Used as an aid to the explanations to the Kangxi Emperor.

In: China: hemel en Aarde, Bruxelles, 1988, p. 395 - detail.

Instrument made under the supervision of Ferdinand Verbiest, in 1669.

Used as an aid to the explanations to the Kangxi Emperor.

In: China: hemel en Aarde, Bruxelles, 1988, p. 395 - detail.

Be that as it may, it was during the years 1660-1665 that Verbiest was prepared by Schall for his manifold duties at the Astronomical Bureau, himself well-versed in this function for about twenty years. Direct evidence on Verbiest's activities in these formative years is rather scarce. However, from the information available it appears that he was well prepared to defend the orthodoxy of the position of Director of the Astronomical Bureau against various attacks both from Europe and by his fellow Fathers, in China. This is demonstrated by his apologies for Schall. 2 In the same field, two decades later, in February 1685, he claimed in unequivocal terms that he was the author of the Minli bijiehuo, which was published in 1661/1662 under the name and authority of Schall. On a more technical level, he was already mentioned as Schall's helper during a difficult mechanical operation as early as 1661 - and again in 1663 -, anticipating his various engineering tasks on the Emperor's behalf, outside the scope of the normal duties of a Bureau Director. The most splendid testimony of his growing acquaintance with practical astronomy is a recently found introduction to his yixiangtu drawings of 1674, already dated in 1664. This proves that the future successor of Schall progressed quickly in the field of instrument building and it may be assumed that the founding of a new Astronomical Observatory, with instruments of a European type (ie: in the Tychonian tradition), was already being planned and prepared as early as 1664. Such plans, if they were really made at such an early date, were brutally interrupted by the Yang guangsheng episode (1665-early 1669), which implied, inter alia, a brutal if temporary return to the former Chinese calendar and its calculation methods. In 1665, during the Jesuit trial Verbiest demonstrated (16th of January 1665) his expertise in the area of eclipse prediction, having been instructed by his master Adam Schall. 4 When, between Christmas 1668 and February 1669, several gnomon tests and astronomical predictions again clearly demonstrated the technical superiority of Western astronomical lore over its contemporary Chinese counterpart, Verbiest and his two fellow Fathers were liberated, himself being nominated, after a complex bureaucratic procedure, to the office of Director of the Astronomical Bureau, with Schall's case as precedent.

Before illustrating the various tasks of this important function, I would like to dwell briefly on the true meaning of Verbiest's title and his real position within the Bureau on the basis of information provided by the petitions recently released by the research of W. Vande Walle.

Detail of the instrument made under the supervision of Ferdinand Verbiest.

It is inscribed: "Kangxi, eighth year, Summer. Made by his subject Ferdinand Verbiest and others."

In: China: hemel en Aarde, Bruxelles, 1988, p. 395 - detail.

Detail of the instrument made under the supervision of Ferdinand Verbiest.

It is inscribed: "Kangxi, eighth year, Summer. Made by his subject Ferdinand Verbiest and others."

In: China: hemel en Aarde, Bruxelles, 1988, p. 395 - detail.

It appears that, after a first proposition of the Liju was cancelled by the Emperor, a new proposal being formulated on the 23rd of March 1669, pleading for a promotion of Verbiest to the 'rank' and 'class' of Vice-Director of the Jianfu (Bureau). This proposition, endorsed by the Emperor on the 23rd of March 1669, was eventually transposed by the Ministry of Personnel into a nomination to the brevet 'rank 9'of Vice-Director "in charge of the affairs of the Bureau" and endorsed by the Emperor on the 1 st of April 1669. However, for reasons connected with his vows as a Jesuit priest, Verbiest could not accept even this 'semi-official' position and tried to refuse the title, to which he eventually succeeded three months later, on the 12th of July 1669, 5 when the Emperor - in a bureaucratic gesture almost without precedent - charged him with the Affairs of the Bureau, without the formal rank this normally implied. The office itself was described as zhili lifa, (ie: "[responsible for] the method of calendar calculation"). This apparently remained so until the end of his life in spite of several other attempts by the Emperor and in spite of some unclear references to such a promotion in later times. In fact, there are allusions to this complex bureaucratic process in documents written at that time, but the final result, with its delicate distinction between the actual authority and the bureaucratic formulation was simplified by summarizing it in the term praefectus, after the precedent of Schall. This general term receives - always after the same model - a further qualification, either Tribunalis Astronomici (referring to the Astronomical nomical Bureau) or Academiae Astronomicae (preferring a reference to the Western Astronomical School), thus avoiding the term 'tribunal' with all its unwelcome juridic associations. 6 With this appointment, Verbiest now became responsible for the whole of the Astronomical Bureau, which by tradition was subordinated to the Liju (Ministry of Rites), but in his time became independent of it, 7 although the meaning of this remark is still unclear. It is also possible that some parts of the Bureau' s body, namely the Geomantic Department within the Chronology Section (cf. §5), operated independently of the Director. As for the Bureau's structure, it may have been roughly the same as in late Qing times, as described by John Porter. On the other hand, several low-ranking officials are occasionally mentioned, 8 which do not figure in Porter's stemma. Some other deviations from this model may also be possible. Verbiest's attitude towards his personnel, which he had to introduce, again, to the Western Rule (cf. §6), is characterized by concern for a good remuneration and promotion prospects (eg: petitions), for only then, in his view, could they become motivated to fruitful cooperation (cf. §6). On the other hand, the response by the staff members to this appeal was twofold: several officials were christianised, but others silently waited for an opportunity to discredit the position of their Western Director and his Rule, as was proved on the occasion of the lunar eclipse of 1681. 9

In the following chapter, I will describe Verbiest's regular duties within the Bureau mainly on the basis of European sources, such as his Latin Treatises, the Astronomia Europœa and other Latin evidence, occasionally completed with information from Chinese sources, especially concerning the Verbiest petitions.

§2. THE CALENDARS

The production, promulgation and distributon of the annual calendar(s) were entirely under the jurisdiction of the Shixian ke or Like (Calendrical Section). Through the qualification zhili lifa, the calendar and its reform were part of Verbiest's original duties, his appointment implying for the calendar's calculation the return to Western Rules - introduced in 1644, and abolished again during the Yang guangsheng period - and the re-training of the officials in this sense (cf. §6).

The calendar was henceforth produced in the buildings of the Liju (Western School), adjacent to the Xitang Residence. 10 This was certainly not only a matter of practical convenience, but also a gesture of high symbolic value; there hardly could be imagined any better proof of the Jesuit control over the Chinese calendar than this topographic location of its production centre.

Voyages du Pere Verbiest a la suite De L'Empereur De La Chine dans la Tartarie Orientale.

In: DU HALDE, Jean-Baptiste, S. J., Description de la Chine, A La Haye, 1736, vol. 1, p.95.

Voyages du Pere Verbiest a la suite De L'Empereur De La Chine dans la Tartarie Orientale.

In: DU HALDE, Jean-Baptiste, S. J., Description de la Chine, A La Haye, 1736, vol. 1, p.95.

The work itself existed mainly in an adaptation - through mathematical derivation and conversion - of the European tables. These tables were available eg: in the famous Argoli edition, explicitly indicated as the basis of Verbiest's calendars, 11 of which even the copy used - as the user's marks testify! - is still preserved; 12besides Argoli, several other tables were also used. The main part of the calculations has a repetitive character and therefore we may surmise that Verbiest entrusted this to the trained officials of the Calendrical Section, his own intervention being restricted to a final check!? This, at least, is what he himself claims to have done with the "Perpetual Calendar".13

Several distinct types of calendars were produced each year. In accordance with Verbiest' s own presentation, mainly in the Astronomia Europœa, these can be listed and identified as follows:

(a) the Minli (Calendarium vulgare), this is the common name of the Huangli (Official Calendar) of the early Qing until the reign of the Xianlong Emperor (° 1736-† 1799) when, for taboo reasons, it was dropped and replaced by the name shixianshu. 14 Verbiest's description15 thus contains an interesting glimpse of the original designation. This description only concerns the first part of this calendar, the lifa (the strictly calendrical part), but omits any further reference to the bush (second part), with the "election of the (in)auspicious days", either because it did not fall under his responsibility (cf. §6) or to avoid vehement reactions from his European readers. The involvement of the Jesuits in this part of calendar making was indeed the subject of much discussion, at least after Schall' s time. The calendar was printed for general distribution.

(b) The Shangweili (Calendarium planetarum)16 which, according to the first draft of the Astronomia Europœa - the Compendium Historicum (1675/1676)17 - was only distributed to the Courtiers and the Ministries of Beijing. In 1680, an official demand by the Bureau for a more general distribution - in order to counter the impact of the non-official Tungshu calendars -18 was denied.

(c) The third calendar, only available in manuscript, and offered exclusively to the Emperor19 - the Shangli20 or Shangweili. 21

The three calendars, here described in a text of 1679/1680 - of which the first draft dates back to 1675/1676 -, conform well with Morgan's description which is based on an official text of 1699 published in the Taqing huidian. 22 This is reminiscent of the case of another official text, published in the same Taqing huidian, 23 which deals with the procedure of the promulgation and the distribution of the calendars at Court, on the 1st of the 10th month of each reigning year, which in turn seems, in general and even in many details, prefigured by a description in the Astronomia Europœa. 24 In both cases, Verbiest is demonstrably close to the official texts of some decades later. Therefore, an earlier version of the latter could have been the substratum of these Latin descriptions, giving these Verbiest chapters a semi-documentary value.

The timing of the calendar production is described in the Astronomia Europaea, 25 where it again corresponds substantially with the prescriptions of 1699 in the Taqing huidian. 26 In both sources it is said that:

(a) on the 1st of the 2nd month of each reigning year, a model of the Minli calendar of the next year had to be shown to the Emperor, for approval;

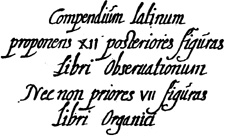

Calligraphic frontespiece.

In: VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., Compendium latinum proponens XII posteriores figuras Libri Observationum nec non priores VII figuras Libri Organici. A work in two volumes: the Liber organicus astronomiae europaeae, Beijing, 1668; and the Astronomia Europaea, Beijing, 1674, title page - detail.

This work contains illustrations of the astronomical instruments installed in the Observatory of Beijing, under the supervision of Verbiest, including a general view of the Observatory and each of the six instruments. The text describes the methods and the mechanical principles used for the construction of the instruments and the building.

Verbiest was one of the only four missionaries who were given the permission to stay in Beijing after all the others were banished from the capital to become practically confined to Guangzhou, following the death of Adam Schall. In the same period, efforts were made to purge the Chinese calendar from Western influence and precision. The resulting mistakes were so evident that eventually they drew the attention of the Kangxi Emperor, who appointed Verbiest as the Director of the Astronomical Bureau.

Calligraphic frontespiece.

In: VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., Compendium latinum proponens XII posteriores figuras Libri Observationum nec non priores VII figuras Libri Organici. A work in two volumes: the Liber organicus astronomiae europaeae, Beijing, 1668; and the Astronomia Europaea, Beijing, 1674, title page - detail.

This work contains illustrations of the astronomical instruments installed in the Observatory of Beijing, under the supervision of Verbiest, including a general view of the Observatory and each of the six instruments. The text describes the methods and the mechanical principles used for the construction of the instruments and the building.

Verbiest was one of the only four missionaries who were given the permission to stay in Beijing after all the others were banished from the capital to become practically confined to Guangzhou, following the death of Adam Schall. In the same period, efforts were made to purge the Chinese calendar from Western influence and precision. The resulting mistakes were so evident that eventually they drew the attention of the Kangxi Emperor, who appointed Verbiest as the Director of the Astronomical Bureau.

(b) on the 1st of the 4th month of each reigning year, one or two copies of this authorized, official Minli had to be sent to each of the Provinces, to be copied and printed there;

(c) on the 1st of the 10th month of each reigning year, the printed calendar was distributed simultaneously at Court and in the Provincial capitals; in Beijing, a manuscript copy, the Shangweili, being exclusively reserved for the Emperor.

The preparation of this distribution also included the translation of the calendars. While the Chinese Mandarins received the Chinese version, Manchu Mandarins were given a Manchu version, and Mongol officials a Mongol rendition. 27 These translations were made by a separate pool of translators within the Astronomical Bureau, of which the Manchu translators are mentioned once by Schall. 28 Only after successfully achieving his Manchu studies was Verbiest able to exercise a certain supervision over this translation process.

Eventually the printing of the calendars, at least those for the Court and the Beijing area, also came under the responsibility of the Calendrial Section and its Director. This took place before the 4th month of the previous year29 or in that same month. 30 The other calendars were produced individually in the Provinces, on the basis of a possibly printed copy of the official Minli (Court calendar). Theoretically, these too, fell under the responsibility of the Astronomical Bureau and its Director, but occasionally Verbiest expressed his frustration about the lack of any serious control on forgeries, produced and distributed throughout the Provinces.

A letter signed by Ferdinand Verbiest, in which he thanks the benefactors of the China mission.

It contains elegant references to the etiquette of the Court of Beijing and to the importance of Astronomy to Christianity.

A letter signed by Ferdinand Verbiest, in which he thanks the benefactors of the China mission.

It contains elegant references to the etiquette of the Court of Beijing and to the importance of Astronomy to Christianity.

As for their number, I have only indirect information. The number of two-million-and-two-hundred-thousand, in Morgan, 31 as compared with the two-million-and-three-hundred-thousand, mentioned by Smith, 32 must, of course, include the officially authorized copies throughout the whole Chinese Empire. Occasionally we receive some glimpse of the costs of the whole operation. Thus, in 1677 height-hundred taels were paid by the Emperor for the paper needed to print the calendar of the next year. 33 On the other hand, in 1670, the printing for the Bureau Director amounted to thirty taels. 34 Both numbers may refer only to the calendar for the Court and the Beijing area.

About eighteen annual calendars were produced under Verbiest's responsibility (1670/1688). The very first Calendar, drawn up by himself and officially accepted, was that of the 9th year of the Kangxi reign (starting on the 21st of January 1670), which he signed as Jianfu. 35 It will normally have been printed in KX 8:4** (ie: year of 1669: month of May), only two months after he was appointed "[...] in charge of the Calendar"! This first Calendar is to my knowledge not preserved; the items I am acquainted with can be listed and provisionally classified as follows:

(a) Copies of a Minli calendar: A Chinese version of the Minli of 1673, in London; 36 a Manchu version of the calendar of KX 19 (1680/1681), in Berlin; 37 another Manchu calendar of KX 21 (1682/ 1683), also in Berlin. 38 Apparently, a Mongol version of a Minli calendar is, in Copenhagen; 39 its characterization as a Minli steming from the original, handwritten Latin frontispiece (probably by the hand of Verbiest himself): "Hic liber / exhibet Ingressum solis in 12 signa et / semisigna zodiaca ad determinatos / dies cujusque mensis lunaris juxta characteres et idioma Tartarorum [...]" ). 40 In the Mongol title, its chronological setting is placed more exactly in KX 19 (1680/1681).

(b) Copies of the Ch'i cheng, planet calendar or ephemerids: the bilingual planet calendars of KX 10 (1671/1672)41 is mentioned without reference, as is the case for the Chinese calendar of KX 13 (1674/ /1675), 42 KX 15 (1676/1677)43 and KX 18(1679/1680); 44 the Chinese version of the calendar of KX 22 (1683/1684) is in Berlin; 45 that of KX 23 (1684/1685) in Indiana University, the Lilly Library; 46 finally, the Chinese Ch'i cheng of KX 25 (1686/1687) are in the Munich University Library47 and in the Brussels Bibliothèque Royale. 48

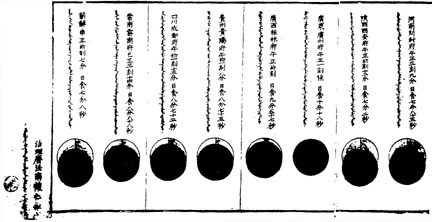

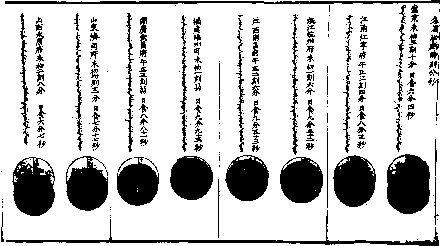

Verbiest's famous prediction of the solar eclipse,

Verbiest's famous prediction of the solar eclipse,

Most of these specimens display an original Latin title page; the most elaborate of them being found on the Chinese and Manchu ephemerids of 1686: "Ephemerides Tartaricae 7 planetarum anni 1686 Tartarice, id est cujusque longitudo, latitudo, hora et minutum, ingressus in novum signum, directio, statio, retrogratio, hora aspectuum praecipuorum, dies apparitionis et occultationis tam matutinae quam vespertinae, distantia eorum ab apogaeo et nodis etc. Summa calculata ad mediam noctem praecedentem sub meridiano Pekinensi a R. P. Ferdinando Verbiest, Societatis Jesu, in regia Pekinensi astronomiae praefecto".

The Latin texts of the former years (eg: 1678) are much shorter. Maybe this transition from a smaller into a much more elaborated formula, giving full technical details, is directly connected with the arrival of Fr. A. Thomas, at Beijing, and his involvement in the work of the Astronomical Bureau. At any rate, his presence in Beijing is behind the sending of a copy (now in Indiana University) of the calendar KX 23 (1684) to Douai, and of a copy (now in Brussels) of the Chinese and Manchu version of the KX 26 (1686) to the Jesuit Residence in Paris.

(c) The Liber conjunctionum lunae cum planetis et planetarum inter se [...] of KX 13 (1674/1675), preserved in the Paris Bibliothèque Nationale49 should display a copy of a Shangweili, 50 but because of its poor physical condition, Bosmans doubts whether this copy was ever presented to the Emperor.

Last but not least, the Kangxi yongnian lifa (Perpetual Calendar) must be mentioned. It concerns a non-recurring issue, for which the initiative was taken by the Emperor himself, at an unknown moment in the early 1670s. Another incitement was the insinuation by Chinese officials that he would be unwilling to communicate the finesses of his calendrical knowledge. 51 Its only purpose was to extend the astronomical tables of the seven planets, published as part of the xinfa lizhu, for the next two-thousand years, guaranteeing the stability of the Manchu Empire ad infinitum. In this case, too, Verbiest delegated the repetitive calculations to his staff. 52 When finished, in 1674, the printing process took another three or four years, the whole being presented on the 27th of August 1678, in thirty two chüan. 53

which occured on the 29th of April 1669, with schematic illustrations showing how the eclipse would be seen in any of the seventeen [sic] Provinces of China.

In: HEE, Louis Van, Ferdinand Verbiest, Bruges, 1913, pp.20-22 • Bibliothèque Royale de Bruxelles.

which occured on the 29th of April 1669, with schematic illustrations showing how the eclipse would be seen in any of the seventeen [sic] Provinces of China.

In: HEE, Louis Van, Ferdinand Verbiest, Bruges, 1913, pp.20-22 • Bibliothèque Royale de Bruxelles.

After his second calendar, Verbiest signed all calendars in his capacity of zhili lifa (responsible for the calendar's making). After the precedent of Schall, 54 this signature was put at the very end of the calendar, 55 clearly restricting his responsibility exclusively to its calendrical part and distancing himself from the buzhu (astrological parts) followed the names of his collaborators. 56

§3. PREDICTION

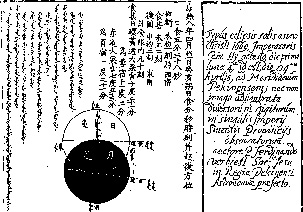

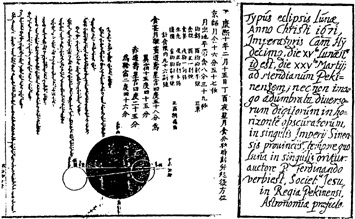

The prediction of solar and lunar eclipses was a product of calculation, and was therefore in the jurisdiction of the Calendrical Section57. The arrival of each eclipse had to be notified six months in advance58 following a strict bureaucratic route. The other preparations were also strictly prescribed. 59 The distribution, within the capital and throughout the Provinces, of an eclipse chart, in order to visualize the evolution of the predicted eclipse, was probably an innovation of Verbiest. I have no information on any earlier copies. In spite of his former experience in this field, 60 all the specimens preserved were issued after Verbiest's appointment as Director, namely:

(a) one map of a solar eclipse (that of the 29th (30th) of April 1669), in the Munich University Library61 and in the Brussels Bibliothèque Royale; 62

(b) two maps of a lunar eclipse (that of the 25th of March 1671 and that of the 6th of June 1686), both in the Munich University Library. 63

These three maps are bilingual (Chinese and Manchu) and provided with a Latin frontispiece. All three were calculated from Beijing ("admeridianum Pekinensem"). Only recently, Nicole Halsberghe has discovered a description of the lunar eclipse of the 11th of February 1683, calculated in Shengjing (ie: Mukden) at 42° latitude. All appearances to the contrary, there can be no direct relation between this piece and Verbiest's journey through Western Tartary of the same year.

Verbiest's famous prediction of the solar eclipse, which occurred on the 29th of April 1669.

Bibliothèque Royale de Bruxelles.

Verbiest's famous prediction of the solar eclipse, which occurred on the 29th of April 1669.

Bibliothèque Royale de Bruxelles.

Another type of document, emanating from Verbiest as Director of the Astronomical Section, are the 'astro-meteorological reports', forecasting the "future disposition of the Heavens [...] and the change in the atmosphere, including its consequences like plague or other diseases, food shortage, etc, indicating also the days on which wind, lightning, rain, snow and other similar phenomena will appear".64 Indeed, according to an anecdote preserved only in Dunyn-Szpot, 65 the Emperor even at his very first meeting with Verbiest had inquired after his ability to present the tianxiang (figura caeli), later - from KX 8 1669/1670) onwards - ordering Verbiest to "investigate the practical applications of astronomy". The latter had both interpreted and restricted the Imperial order in the sense of contemporary Catholic tolerance in the field of astrology. Thus his predictions were of purely meteorological character, limited to the weather forecast and the prediction of the weather's impact on the people and the country (astrologia meteorologica). This is not only proved by the aforementioned paragraph from the Astronomia Europœa, but also by the Yutui Jiyan (Notes on the Verifications of the Predictions), of 1681, 66 which Latin subtitle, Praedictiones temporis, pluviorum, ventorum et eiusmodi, probably is by the hand of Verbiest. Here, we find the reflection of Verbiest's weather forecasts for each year between KX 8 (1669/1670) and KX 19 (1680/1681). Only from 1677 onwards, probably in answer to some legal complaint, 67 did Verbiest publish a new kind of report, of which two-hundred-and- three specimens were recently discovered in the Ming-Qing Archives of Beijing, all issued between 1677 and 1688 - the year in which Verbiest died. Here too, a strong relation with the documents described in Astronomia Europœa68 appears, with "a comprehensive view of the celestial situation, a discussion on the meteorological conditions and accompanying weather aspects, the impact on health, agriculture, political and social conditions, etc, and a reference to similar predictions in divination books";69 the figura caeli in this case being represented by an astro-meteorological diagram which directly imitates contemporary occidental models.

§4. OBSERVATION AND VERIFICATION

Both the verification of the eclipse predictions and the meteorological forecasts, and the observation of the other celestial and meteorological phenomena belonged to the duties of the Tianwen ke (Astronomical Section). They were normally performed by the officials and the students of the Astronomical Section, 70 and had to be done daily and nightly, mainly on the Lingtai (Specula Astroptica or Astronomical Platform) on the Eastern edge of the Beijing City walls.

In case of an eclipse, it was Verbiest himself, accompanied by the other chief members of his staff and by several officials of the Liju, who made the verification, 71 the other 'Mandarins' of the Astronomical Bureau waiting, either in the courtyard of the Liju (solar eclipse) or in the court of the Taichangsi (lunar eclipse). In the meantime, the Emperor, for whom eclipses were of considerable importance, followed these phenomena from inside the Palace, being provided by Verbiest with appropriate instruments. 72 In spite of Verbiest's doubts, due to the uncertainties of the European (Tychonian) tables he was working with, the predictions turned out to be accurate. Any deviation, indeed, would give cause to new opposition from Verbiest's ever alert enemies, as proved by the incident on the occasion of the lunar eclipse of the 4th of March 168173

As for the meteorological predictions, Verbiest's Yutui Jiyan must be mentioned again, as this booklet contains not only Verbiest's forecasts, but also an important closing formula of the official in charge, who reports that, after verification, all the predictions were approved. In consequence, they were filed in the Annals.

Verbiest's famous prediction of the lunar eclipse, which occurred on the 25th of March 1671.

The observors attention was also directed to other 'anomalies' in the Heavens, 74 making no distinction between 'celestial' phenomena, such as sun spots, and meteorological occurrences, such as solar haloes. 75

All nocturnal observations made in the absence of Verbiest by the four shifts of five observors (or five shifts of four observors each) were to be accurately described and reported to him each morning, in a special book, signed by the respective observors. 76 On the basis of this information, Verbiest had to decide whether the phenomenon observed was important enough to be petitioned to the Emperor or not, 77 and to be filed in the Archives. Nothing of all this seems preserved, except some meteorological observations, occasionally jotted down in the margin of several books in the Jesuit Library of Beijing. 78

§5. TIME KEEPING, ELECTION AND ASTROLOGICAL COMPUTATION

These aspects were the work of the louke ke (Water Clock or Chronology Section) of the Bureau. The responsibility of its officials concerned:

(a) the maintenance of the water clocks throughout the Court, for instance on the occasion of an eclipse, and the indication of time, daily and nightly, both within the Palace and in the other parts of the City. 79 In addition:

(b) another part is involved in the indication of auspicious and non auspicious days ('election') for all kinds of human actions, and for other geomantic decisions. 80 Much of the latter information was incorporated in the annual calendar, especially in the second part of the Minli, called buzhu. Although this 'geomantic' section probably worked independently of the Director's responsibility, 81 Verbiest, as early as 1661, had shown the characters xifa after the signature of the Jesuit Head of the Astronomical Bureau explicitly restricting his responsibility to the strictly calendrical part. 82 Moreover, in his previously mentioned Minli bijiehuo of 1661, he tried to remove each superstitious aspect of the buzhu additions in the calendar. 83 Quite logically, by a petition of the 26th of July 1669, very soon after his appointment as the Director of the Bureau, Verbiest tried to cancel these and other superstitious elements, such as the practice of a houqi. In that same year, he dealt further with this topic in three treatises, 84 namely the Wangzhanbian ([Essay on the] Refutation of the Mendacious Astrology), the Wangzebian ([Essay on the] Choice of Propitious Days) and the Wangtui jixiong zhibian ([Essay on the] Repudiation of Astrologic Predictions).

§6. INSTRUCTION

Almost immediately after his appointment, and fully in accordance with his newly acquired responsibilities, as the need for competent personnel was great Verbiest began instructing the officials and students of the Bureau in the secrets of the "new (Western) rule". He even tried to reintegrate former staff members who had been purged during the Yang guangsheng period. A first clear reference to the number of staff employed is found in a letter, dated the 23rd of January 1670, where its number is calculated as "one-hundred and more".85 One year later, on the 1st of January 1671, a new situation was created by the promotion of eighty new Manchu tianwen sheng (students in the Astronomy Section), ten from each Banner School, due to the intervention of F. Verbiest near the Emperor. Probably the most informative source regarding these promotions 86 also contains much other interesting information on the organisation of these lessons. They were given in the Liju, near the Xitang, to the students of each section separately, in rotation, namely, four times a month on a fixed day. The number of students amounted at that time to three-hundred. This number and the position and remuneration of his staff reflects the extraordinary 'revival' of the Astronomical studies and their new appeal. Some years later, however, the number decreased to the more reasonable figure of one-hundred-and-sixty to two-hundred in 1677, 87 which is almost in accordance with the regular number of about one-hundred-and-thirty, as given for the late Qing situation, by Porter. 88

In fact, all Verbiest's Chinese Treatises on Western science may have had the implicit or explicit pedagogic aim to preserve his instruction for future generations; moreover, on some occasions, such as the achievement of the Perpetual Calendar (cf., §2), the Chinese eagerly encouraged him to put the best of his knowledge at their disposal in this way. Pedagogic considerations may have been of particular weight in the case of his yixiangzhui - with the illustrations in the yixiangtu -, as it warranted the Western influence on the Chinese Astronomical Observatory.

§7. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

All in all, this overview may demonstrate that Verbiest had a firm grip on the Astronomical Bureau's main activities, in spite of an always slumbering opposition looking for an opportunity to discredit him, even though he was obliged to respect some Chinese institutions, albeit with disgust. After all, he was responsible for the Calendrical and the Astronomical Sections, which ensured his own position at Court, as well as the position of the China mission. His own missionary influence is limited to the corpus of the Bureau staff where, indeed, many prominent members were christianised. This is the basis both of his own understanding of Chinese sensibilities and his concern for their spiritual anguish in the Rites Controversy, and his position in that dispute. This, however, may be demonstrated in another contribution.

CHINESE GLOSSARY

buzhu 補註

Daqing huidian 大淸會典

houqi 候氣

Huangli 黃曆

Jianfu 監副

Kangxi yongnian lifa 康熙永年曆法

libulifa 禮部曆法

lifa 曆法

Liju 曆局

Like 曆科

Lingtai 靈臺

louke ke 漏刻科

Minli 民曆

Minli bujiehuo 民曆補解惑

qizhengli 七政曆

Shangli 上曆

Shangweili 上位曆

Shengjing 盛京

Shixian ke 時憲科

Shixianshu 時憲晝

Taichangsi 太常寺

Tianwen ke 天文科

Tianwen sheng 天文生

tianxiang 天象

Wangtui jixiong zhibian 妄推吉凶之辯

Wangzebian 妄擇辯

Wangzhanbian 妄占辯

xifa 西法

xifa lizhu 西法曆註

Xitang 西堂

Yang guangsheng 楊光生

yixiangzhi 儀象志

yixiangtu 儀像圖

Yutui jiyan 預推紀験

zhili lifa 治理曆法

NOTES

1 GOLVERS, Nöel, The Astronomia Europœa of Ferdinand Verbiest (Dillingen, 1687). Text, Translation, Notes and Commentaries, in: "Monumenta Serica Monograph Series", Nettetal, Steyler Verlag, (28) 1993, pp.18-19.

2 JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., Correspondance de Ferdinand Verbiest, directeur de l' observatoire de Pékin, Bruxelles, Palais des Académies, 1938, p.41ff.

3 BA: JA, 49. IV.63, fol. 458ro.

4 GABIANI, G., Incrementa Sinicae Ecclesiae, Viennae, typis L. Voigt, 1673.

5 JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p.161.

6 GOLVERS, Nöel, op. cit., p.215, n. 4.

7 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., Astronomia Europœa sub imperatore Tartaro Sinico Cám H'y [...], Dilingæ, J. C. Bencard, 1687, p.13.

8 As in: JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., pp.162, 164.

9 Ibidem., pp.355-356.

10 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.21.

11 Ibidem., p.23.

12 BÉRNARD-MAÎTRE, Henri, S. J., F. Verbiest, continuateur de l'oeuvre scientifique d'A. Schall, in: "Monumenta Serica", Bonn, (5) 1940, p.111.

13 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J.,, op. cit., p.33.

14 MORGAN, C., De l'authenticité des calendriers Qing, in: "Journal Asiatique", Paris, (271) 1983, p.372.

15 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p. 22.

16 Ibidem., p. 23 - For its full description.

17 GOLVERS, Nöel, op. cit., pp.28 -29.

18 HUANG, Yilong, L'attitude des missionnaires jésuites face à l'astrologie et ã la divination chinoises, in: "Mémoires de 1' Institut des Hautes Études Chinoises", Paris, (5) 1993, p.93.

19 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.23.

20 MORGAN, C., op. cit., p.372.

21 SMITH, R. J., Fortune-Tellers and Philosophers. Divination in Traditional Chinese Society, Boulder et al., Westview Press, 1991, p.76.

22 Ed. Ta Ching hui tien, 1908 [reprint], Taipei, Shangwu, [n. d.,] chap. 161, pp.2a-4a.

23 Ibidem., chap. 36, pp. 4b-5a.

24 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., pp.25-26;

GOLVERS, Nöel, op. cit., p.222, n.1.

25 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., pp.22-23, 25.

26 MORGAN, C., op. cit., p.370 ff.

27 SMITH, R. J., op. cit., p.75.

28 SCHALL, Johann Adam, S. J. Relation Historique. Texte latin avec traduction française du P. P. Bornet, SJ., Tientsin, Hautes Études, 1942, p. 167.

29 Ibidem., p.25.

30 JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p.161.

31 MORGAN, C., op. cit., p.374.

32 SMITH, R. J., op. cit., p.75.

33 PIH, Irene, Le Père Gabriel de Magalhães, Paris, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1979, p. 196.

34 JOSSON, H.- WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p. 163.

35 Ibidem., p.161.

36 BL: 15298 a.29; MORGAN, C., op. cit, p. 383.

37 FUCHS, Walter, Chinesische und mandjurische Handschriften und seltene Drucke, Wiesbaden, F. Steiner Verlag, 1966, no240.

38 Ibidem., no 241.

39 KB: Mong. 522; HEISSIG, Walther - BAWDEN, Charles, Catalogue of Mongol Books, Manuscripts and Xylographs in the Royal Library, Købnhavn, 1971, p. 183.

40 Compare with: VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., pp.22-23.

41 PFISTER, Louis, S. J., Notices biographiques et bibliographiques sur les Jésuites de l' ancienne mission de Chine, 1552-1773, Chang-hai, Imprimerie de la mission catholique, 1934, vol. 1, p.356, no 20.

42 Ibidem., vol.1, p.356, no 21.

43 Ibidem., vol.1, p.356, no 22.

44 Ibidem., vol.1, p.356, no 23. See: CARTON, C., Notice biographique sur le Père F. Verbiest, Bruges, Vandecasteele-Werbrouck, 1839, pp.71-72 - Vaguely referring to Paris.

45 FUCHS, Walter, op. cit., no 125.

46 CROUCH, Archibald Roy, Christianity in China, New York, 1989, IN-15/1; PFISTER, Louis, S. J., op. cit., vol. 1, pp.356-57 - With its Manchu translation noted, without reference.

47 UB: 2° P. or.17.

48 BNP: chap.4926 - In accordance with: Verbiest, Ferdinand, S. J.,, op. cit., p.23.

49 VAN HEE, L., Ferdinand Verbiest, écrivain chinois 1623-1688. Bruges, L. de Planche, 1913, 8428 C/LP. Idem., 8011 C/LP - In a Manchu version.

50 VAN HEE, L., op. cit., pp. 16-17; BOSMANS, H., op. cit., pp. 279-280 - For its description.

51 ARSI: Jap.-Sin., 109, II fols.127-128.

52 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.33.

53 GOLVERS, Nöel, op. cit, pp.236-237, ns.12-14.

54 VÄTH, A., Johann Adam Schall von Bell S. J. Neue Auflage, in: "Monumenta Serica Monograph Series", Nettetal, Steyler Verlag, (25) 1991, pp.271-272; JOSSON, H. -WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p.73.

55 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., pp. 19-20.

56 MORGAN, C., op. cit., p.367; FUCHS, Walter, op. cit., nn.240, 242.

57 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.32.

58 Ibidem., p.30.

59 Ibidem., p.31.

60 GABIANI, G., op. cit., p.229 ff.

61 UB: 2° P. or.32,33.

62 VAN HEE, L., op. cit., 31074 C/LP.

63 UB: 2° P. or.35, and UB: 2° P. or. 34 - Respectivelly.

64 VERBIEST, F., op. cit., p.29.

65 ARSI: Jap.-Sin., 104, fol.206ro.

66 Ibidem., 45a.

67 HUANG, Yilong, op. cit., p. 100.

68 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.29.

69 KONNINGS, P., Astronomical Reports Offered by F. Verbiest S. J. to the Chinese Emperor, in: INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE IN CHINA, Cambridge, June 1990 - Oral communication.

70 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., pp.48-49.

71 Ibidem., p.31.

72 Ibidem., p.32.

73 JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., pp.355- 356.

74 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.48.

75 Ibidem., pp.93-94.

76 Ibidem., p.48.

77 Idem.

78 BÉRNARD-MAÎTRE, Henri, op. cit., p. 111.

79 VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.33.

80 Idem.

81 VÄTH, A., op. cit., p.273.

82JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p.65 ff.

83VAN HEE, L., op. cit., pp.35-36.

84Ibidem., pp.37-44.

85JOSSON, H. - WILLAERT, L., op. cit., p. 162.

86BA: JA, 49. V.16, no89, fol.411vo.

87VERBIEST, Ferdinand, S. J., op. cit., p.49.

88PORTER, John, Bureaucracy and Science in Early Modern China: the Imperial Astronomical Bureau in the Ch'ing Period, in: "Journal of Oriental Studies", Hong Kong, (18) 1980, p.64.

* Researcher on the Jesuit Missions in China in the seventeenth century and on the life and work of Ferdinand Verbiest, S. J.; Ph. D in Classical Philology (Leuven). Professor of Latin (Hervelee-Leuven). Member of the Verbiest Project and researcher of the Verbiest Foundation. Author of several articles and publications on Verbiest and contributor to the Verbiest Courier.

**The traditional Chinese calendrical year does not coincide with the conventional European calendrical year. In the text the dash sign (/) connects dates of an official Chinese Imperial period; and the hyphen (-) connects dates related to the common Western almanac. In referring to KX entry dates, the notations in the text follow the established norm; for instance: KX 4:8 stands for the fourth month (May) in the eighth year (1669) of the Kangxi reign (Kangxi [K'ang-hsi] being the official name for the reign period of Emperor Hsüan-yeh).

start p. 201

end p.