§1. INTRODUCTION

From the late sixteenth to the early eighteenth century, the Jesuits had been sending the most eminent of their Order to China, through Macao, to spread the Christian Faith. Since the Portuguese were the first Europeans to arrive by sea, every Bishop had to be presented by the Portuguese Government, and every missionary had to sail on a Portuguese ship. Macao, "the Rome of the Far East and the Mother of missions in Asia," rightly deserves her title; Macao has upheld the motto of the Portugese explorers: "to propagate the Faith and the Empire and, to bring the Gospel of Jesus Christ and to win souls for the Church."1 Transported by the Portuguese and carried by Jesuit missionaries, the incidental relation between spreading Christianity and disseminating the ideals of Baroque Culture is manifested by the architecture of the Church of St. Paul(1602-1627).

The presence of St. Paul's residual facade provides us with a discursive space for historical imagination and a spatial discourse for collective memory: imagining and remembering from its corporeal image. Its discursive presence recalls the Portuguese maritime expansion and, through it, the incidental transportation of Christianity to China; its spatial history indirectly narrates the Jesuitic development of their concept of perspectival space through which they transformed the Artistic realms of the World. St. Paul's stone facade remains a dramatic edifice of time and space which enunciates an academic anecdote of architectural theories transpired through Macao.

Seen in isolation, the St. Paul's façade devices and elements often look "puzzling enough" in their own way, but related to a Baroque architectural structure "they [have an] essential [...] purpose" encoding a narrative system of geometry expressed through the manipulation of light, surface texture and perspectival effects. 2 Involving the spectator's perceptual senses in the Baroque Church design and portraying religious narratives on its walls had an intentionally evangelistic aim at epiphany. The geometric ensemble 'forged' a theatrical and emotional 'assault' on the spectators, enmeshing them in a spatial geometry whose lines, never still, intended to lead them from one enclave to the next, involving them in a drama depicted via a series of pictorial reliefs, confusing the spatial domains of Art, structure, illusion, and reality. The Baroque artists desired to enter into the multiplicity of phenomena in perpetual becoming; their compositions were dynamic and tended to expand outside their designated boundaries; their lexicon of elements, forms and devices were affiliated with a 'hidden' narrative system of geometry and were inseparable from each other. Such architectural denominators contributed and reflected the Jesuitic involvement in their contemporary exchange of ideas between the Orient and the Occident.

§2. THE ART AND SCIENCE OF THEOLOGY

Catholicism of the Counter-Reformation possessed an effective mechanism in its ability to use visual communication. Through the emotional stimuli of Divine imagery of Art, the believer was lead to grasp the meaning of the liturgical teachings of the Church. Two types of imaginative processes were then employed by the Jesuits: one which developed from the writen and spoken forms of expression leading to visual imagery and another which departed from visual images conducting to verbal expression. Great emphasis was particularly given to cultivate their members power of imagining from words to visual images. At the very beginning of his Ejercicios espirituales (Spiritual Exercises) Ignatius of Loyola (°1491-†1556) prescribes internal ordering before proceeding to "visual composition seeing the place" in terms that might be instructions for the mise-en-scène of a theatrical performance:

"The first prelude is composition seeing the place. It should be noted at this point that when the meditation or contemplation is on a visible object, for example, contemplating Christ our Lord during His life on Earth, for He is visible, the composition will consist of seeing with imagination's eye the physical place where the object that we wish to contemplate is present. By the physical place I mean, for instance, a temple or mountain where Jesus or Our Lady is, depending on the subject of the contemplation."3

The reference here to a locus and an imago is obvious of the two basic ingredients of the Ars memorativa (The Art of Memory). For Ignatius, "composition" is involved with internal ordering to proceed to meditation in the memory theater as practiced in the sixteenth century. This Prelude is to be the first step in every meditation throughout the four Spiritual "weeks", with adaptations to suit the subject matter and the specific objective of each week. In the first day of the second week the Spiritual Exercises opens up a vast visionary panorama:

"The first point is to see all the different people on the face of the earth, so varied in dress and in behavior. Some are white and others black, some at peace and others at war; some weeping and others laughing; some well and others sick; some being born and others dying, [...].

Second, to see and consider the Three Divine Persons seated on the Royal throne of the Divine Majesty, how they behold the entire face and vastness of the Earth and all the people in such great blindness, and how they die and go down into Hell.

Allegorical frontespiece.

In: NADAL, Hieronymus, S. J., Evangelicœ historiœ imaginœs [...] auctore Hironymo Natali [...], Antuerpiæ, Societatis Iesu, 1593, title page.

Allegorical frontespiece.

In: NADAL, Hieronymus, S. J., Evangelicœ historiœ imaginœs [...] auctore Hironymo Natali [...], Antuerpiæ, Societatis Iesu, 1593, title page.

Third, I will see our Lady and the angel who greets Her. I will reflect, that I may draw profit from such sight."4

Then Ignatius goes on to invite the readers to visualize the Temple of Jerusalem, the synagogues in which Christ preached, and the towns through which He passed. The overwhelming importance which Ignatius accords to the sense of sight in following Cicero's percept, above all, his insistence the use of "corporeal similitudes" to his imagines provide evident links with the Ars memorativa, not in its Classical notion, but as transformed in the Middle Ages to serve purely religious ends, particularly by St. Thomas Aquinas. 5 The Ignatian meditations call for the exercise of artificial memory rather than of natural memory in the mnemotechnical notion of the Ars memorativa. The loci and imagines of the Spiritual Exercises are based on the Scriptural narrative. The loci, for instance, consist of a variety of places, each appropriate to the meditation in question. They do not consist, as in the Ars memorativa, of a specific temple, theater, or similar setting in which mnemonic notae or imagines are placed, to be plucked out subsequently at the appropriate time. Ignatius provides memory 'points'; through language describes how to imagine, but the images to be imagined are absent from the Spiritual Exercises. His insistence on meditation in the "memory theater" has one clear aim: to bring out the pure image, the uncontaminated image, the image in perfect solitude, the original image, the Divine image. The image obtained through meditation in the "memory theater" is the perfect image, for it is in it and through it that God's signs will appear. The image will turn to language and return to the public domain. What distinguishes Ignatian procedure, even with regard to the forms of devotion of his own time, is the shift from the word to the visual image as a way of attaining knowledge of the most profound meaning.

The Annunciation

In: NADAL, Hieronymus, S. J., Evangelicœ historiœ imaginœs [...] auctore Hironymo Natali [...], Antuerpiæ, Societatis Iesu, 1593

The Annunciation

In: NADAL, Hieronymus, S. J., Evangelicœ historiœ imaginœs [...] auctore Hironymo Natali [...], Antuerpiæ, Societatis Iesu, 1593

More intriguing, the Jesuit liturgical teachings reverse the direction of meditation stated in the Spiritual Exercises: from a given image - proposed by the Church itself and not first 'imagined' by the believer - to arrive at a liturgical meaning. The point of departure and the point of arrival are previously established by a given 'image', but, in the middle, "there opens up a field of infinite possibilities in the application of the individual imagination, in how one depicts characters, places and scenes in motion."6 This notion of memory is best illustrated by Hieronymus Nadal's (° 1507-†1580) supervision of the engravings' contents in his liturgical book Evangelicœ historiœ imagines[...] (Images of Spiritual History[...]) in which Biblical scenes are illustrated in perspective and by which the believers begin to have accesses to 'imagining' and 'remembering', as practiced by a sixteenth-century scholastic man, like Ignatius. A Jesuit missionary, such as Matteo Ricci (°1552-†1610), had to rely on Nadal's book to pedagogically demonstrate the 'image' of God in his liturgical teachings and to assure the Chinese that the notion of God was not only real but that God was, indeed, omnipresent. 7 With memory objects acting as images' substitutes, Jesuitic Art placed particular emphasis in the Classical and mnemotechnical use of the Ars memorativa for religious purposes. Jesuitic visual communication emphasize a development of perspective in religious painting thus playing an important role in propagation of the liturgy credo. Especially the science of perspective and its technics and techniques have an analogous relationship with the Ignatian's composition of visual imagery, in which adequate and faithful depictions of Biblical scenes are instrumental in guiding the believer's Spiritual life. Although the Jesuits never claimed an Art imbued with a style of their own, they have ennobled theories and practices of perspective in their religious architecture and literature. 8

§3. THE SCIENCE AND THEOLOGY OF ART

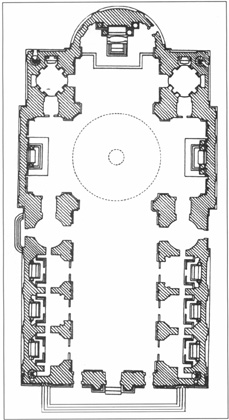

Baroque Culture was intimately bound up with the Counter-Reformation and in particular with the Society of Jesus alliance of Art with science and religion. Examining the volumetric concept of the Gesù, in Rome - the first Jesuit Church designed by the Jesuit priest Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola (°1507-†1573) - one may find how the Jesuits were concerned with the science of acoustics and optical effects in their sermons. This concern was reflected in the Gesù's Church plan which ennacts a lecture-hall-like geometry derived from a combination of a central core (its monumental dome) and a basilica nave (reduced, however, to a single gallery; the side aisles being replaced by contiguous chapels). The façade of the Gesù - finished by Giacomo della Porta (°1532-†1602), in 1575 - came to serve served as a prototype for many later Baroque Churches, including St. Paul's, in Macao.

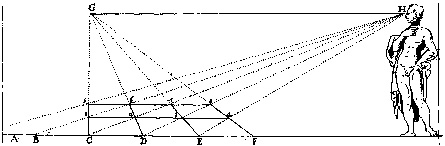

Demonstration of the second regola (rule), or the distance-point method.

In: VIGNOLA, Giacomo Barozzi da, Le due regole della prospettiva practica, Roma, 1583.

It does not exist any 'image' in the 'construction' because it does not exist any framed 'window' through which one can observe.

Demonstration of the second regola (rule), or the distance-point method.

In: VIGNOLA, Giacomo Barozzi da, Le due regole della prospettiva practica, Roma, 1583.

It does not exist any 'image' in the 'construction' because it does not exist any framed 'window' through which one can observe.

Not only had Vignola established a Jesuit model for the Baroque Church using geometrical orderings but, in 1583, he also explained "Jesuitic perspective" as the 'distance-point method' of linear perspective - also known, in contemporary terms, as 'the workshop method'. The 'distance-point method' divides lines to obtain ratios between them without defining vanishing points. This technique could be manipulated to produce a unified central perspective without designating an enframement, as favored by Alberti's Quattrocento vanishing-point perspective. Although Vignola's Treatises: Regole (Rome, 1562) and Le due regole della prospettiva practica (Rome, 1583), were more practical than Serlios' Books I to V (1584-1547), and had better illustrations with clearer procedures, the 'distance-point method' was unable to convince Italian commentators to imagine perspectival effects without constructing a-priori the picture frame. Nonetheless, the 'distance-point method' became favoured in the artists workshops of Northern Europe and proved effective in construing a cartographic vision of a new World expanded by the voyages of the Age of Discovery. 9

Through the science of perspective, the Jesuits were able to merge Art and science, astronomy and architecture to Christianity thus ordering nature and "supernature" in geometrical relationships, and represent terrestrial and celestial spaces in ruled pictorial terms. The Jesuitic use of linear perspective derived from a unique way of thinking that embraced the entire Universe, from the infinite to the infinitesimal, being considered a crucial constituent of comprehensive knowledge. For the Jesuits, it was significant to assert that Divine infinity could be pictorially represented in tangible spaces without recurring to a predetermined vanishing point. The 'invention' of Illusionism alluded to movement, flight, instability, metamorphosis, magnificence and paradise.

In La perspective pratiquée par un Parisien, religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus, Jean Dubreuil expressed that a Jesuit ecclesiastical function was to 'control' the World through perspectival order. With Dubreuil, then, "every natural and architectural phenomenon that could be reduced to perspective would be so reduced; every form of unconcealed change being submitted to the general discipline of perspective."10 Moreover, the good "religieux de la Compagnie de Jesus" was concerned with the application of perspectival decoration to every aspect of his life as well as to theater. The minutiae with which Serlio worked out the vanishing points of his Treatises' perspective exercises had little to do with Vitruvius guidelines in his Ten Books on Architecture and more to do with the maturation of the Baroque illusionistic stage. He certainly paved the way for the Jesuits to merge their ecclesiastical illusions with a theatrically ficticious representation of space.

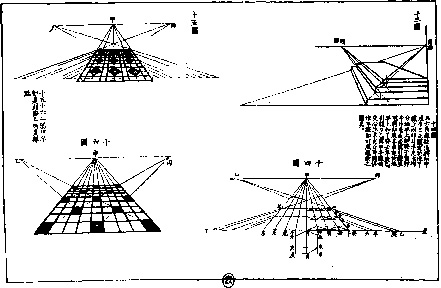

Depiction of a perspectival construction according to Giuseppe Castiglione.

In: NIAN XI YAO, Shixue (Visual Techniques), first edited in 1729 and reprinted in 1735.

Derived from Andrea Pozzo's Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum.

Depiction of a perspectival construction according to Giuseppe Castiglione.

In: NIAN XI YAO, Shixue (Visual Techniques), first edited in 1729 and reprinted in 1735.

Derived from Andrea Pozzo's Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum.

With scientific conviction in religion, Andrea Pozzo (° 1642-†1709), after Jean Dubreuil, was a self-proclaimed "lover of perspective". His dizzying illusionism epitomized Jesuit ecclesiastical 'illusions' as 'theaters' of the World. Pozzo's Treatises, Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum, two independent volumes, published in 1693 and 1700, included engravings of his real and ephemeral architecture. In Pozzo's eyes, the whole point of illusion was to be able to miraculously coalesce the distorted chaos of shapes into a coherent revelation, when viewed from a determined location. In his writings Pozzo firmly stated that he intended "with a Resolution, to draw all the lines thereof to that true Point: the Glory of God."11

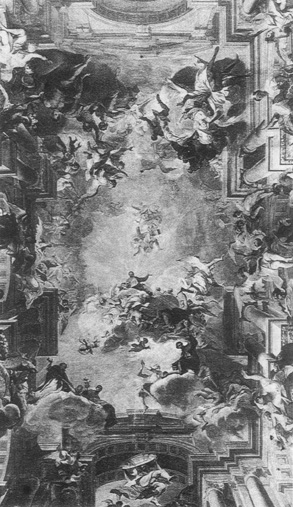

In Pozzo's theater design, the point of infinity in the stage scenery, alluded to by the angled flats, mirrored the privileged location of the Royal box where the single-point-viewing perspective incarnated the epiphany of the ideal. In the case of the nave vault, The Glory of St. Ignatius (1688-1694; Rome, S. Ignazio), the perspectival vanishing point coincides with the pictorial position of the Son of God who, in Pozzo's own words, "send[s] forth a ray of light into the heart of Ignatius, which is then transmitted by him to the most distant regions of the four parts of the World."12 As a virtuoso of Illusionism and master of that famous Italian perspectival trucage known as di sotto in su (from below upwards). In St. Ignazio, Pozzo excelled his talents bringing the pictorially depicted Paradise down to within sixty feet of the nave's floor, thus emulating the motto of the Society of Jesus: Ad majorem dei gloriam (To the Greater Glory of God). The frescoed nave vault contains a perspectival system of optical dynamics acting as a conically expanding core of vision, its pictorially represented rays of spiritual energy - as they surge from the composition's central focus - radiate to the peoples of the World through strategically pictorially positioned Jesuit missionaries.

Plan of the Gesù (ca 1568-1575), in Rome, by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola

Plan of the Gesù (ca 1568-1575), in Rome, by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola

The term, Arti del disegno, from which the nomenclature Beaux Arts probably derived, was originated by Giorgio Vasari (°1511-†1574), who initiated it as the guiding concept for his well-known collection of artists and architects biographies. The notion of Arti del disegno marked a change in artistic theory which found its institutional expression, in 1563, when in Florence, again under the personal influence of Vasari, painters, sculptors and architects severed their working methods with some craftsmen's guilds and formed the Accademia del Disegno (Academy of Design) - the first of its kind, pioneering a model for later similar institutions in Italy and other countries. 13 The idea that disegno could serve as the foundation for Art and science was born out of the debates between the Platonism of Florence and the Aristotelianism of Padua, in the late sixteenth century. At first, the notion of disegno was directed to the kind of drawings that referred not to the appearance of things but to a selectivity and ordering prescribed by the judgement of the artist and in particular to the ordering of the human body. Establishing disegno as the basis for rendering things selected from nature allowed an artist to command an eye to nature, the real, and another to beauty, the ideal.

Federico Zuccaro's L' Idea de' pittori, scultori e architetti (1607) has been regarded as the last contemporary literary chronicle- cum -Treatise on Italian Renaissance Art and as the furthest theoretical development of the idea of disegno. 14

Federico Zuccaro (°1542-†1609) was the founder of the Accademia di San Luca, in Rome. 15 For Zuccaro, disegno (which means drawing, or more specifically, drawing through lines) should become the foundation of all Arts. Once this scientific foundation was established, the Arts (with their characteristic rules and procedures) would then be free to find their adequate places among all human activities. Zuccaro defined a 'line' as a "simple lineamento, circumscription, measurement and shape of whatever real or imagined thing [- as the] proper body" and visible substance of disegno interno. 'Line' was "simply the operation of forming something [; it] declares and expresses [an] ideal image [formed in the mind, and is called disegno because [it] signifies and shows, to sense and intellect, the form of the thing formed in the mind and impressed in the idea." 'Line' stood between the true disegno interno - which is in the concetto formed by the soul - and its realization in the colours of painting or the stone of sculpture. 16 For Zuccaro, not only did knowledge arose from sensation, but it was also necessary for all sciences to assume sensible form.

Andrea Pozzo: The "corridoio" (1608).

A small frescoed gallery adjacent to the accomodations of St. Ignatius, in the Gestù College, in Rome.

The distorted perspectivation of the imagery frescoed on the straight parallel walls of the gallery continuing throughout its coved vault give an illusion of a symmetrically correct space.

Andrea Pozzo: The "corridoio" (1608).

A small frescoed gallery adjacent to the accomodations of St. Ignatius, in the Gestù College, in Rome.

The distorted perspectivation of the imagery frescoed on the straight parallel walls of the gallery continuing throughout its coved vault give an illusion of a symmetrically correct space.

Zuccaro depicted an Allegory of disegno on the ceiling of one of the rooms in his house, the so-called Sala del Disegno. The ceiling painting is a sharply foreshortened, bearded Allegory of Disegno, surrounded by the female Allegories of the three Arts of Disegno: Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. Disegno is depicted haloed by three wreaths symbolizing the trinitarian unity of the three Arts and gazes upward to a higher source of light, toward which he seems to be ascending. At the apex of the composition, medallioned inscriptions read: "light of the intellect and life of activities; one light shining in three." Disegno is humanly characterized as a light-form, derived from the ultimate and central light of the Divine grace, which, as a light to the intellect, must be higher than the bearded Allegory which, in his own terms, equally is a light that becomes refracted in the subordinate lights of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture. 17 Zuccaro offered the belief that disegno was the creative force of the human mind, evident in all our activities; activities which include the sensation and the conduct of life to the most marvelous achievements of Art and the loftiest feats of speculation, a mirror of the Divine creativity, of the ordained World, continually regenerating this human creative force into existence. It is therefore not difficult to imagine that Zuccaro's adaptation of Aristotelian psychology and Platonic ordering to formulate the idea of disegno in painting, sculpture and architecture had far-reaching implications for both pedagogy and propaganda, thus appearing with increasing frequency in Counter-Reformation Art literature and its derived applications. 18 Naturally, the Jesuits embraced the idea of disegno and its flourishing practices in the recently founded Academies, in Italy. Deriving intellect from the absolute light of God, defining 'line' as the essential element of Divine order and codifying the World into a geometrical hierarchy containing a disciplined, constructed and quantifiable idea of Art, particularly suited Jesuit metaphysics and the logic of which Matteo Ricci and his followers wished to model the mathematical sciences and, ultimately, their missions.

§4. THE ART OF SCIENCE AND THEOLOGY

Matteo Ricci, the founder of the Society of Jesus China mission, was the first to realize that, in order to spread the Christian Faith, to enlarge his audience and above all, to convert the Chinese literati and high officials, it was advisable to present himself not as a humble missionary who had taken the vow of poverty but as a radiant Ambassador of Western science. 19 Ricci was sure that if the Emperor's Mandarin scholar-bureaucrats became convinced of the superiority of Western science, they would similarly succumb to the logic of Roman Catholic Christianity. 20 To do so with China, with its millions of souls for Christ, would mean achieving the greatest Christian victory since the conversion of the Roman Empire. The triumph of Christianity over Buddhism, in China, could easily be obtained by demonstrating the impeccable power of Western science through intellectual inquiry into Catholicism. Without any hesitation, Ricci brought two important books to China: Hieronymus Nadal's Evangelicœ historiœ imagines [...] and an anotated and illustrated copy of Euclid's Elements of Geometry by a Jesuit mathematician, Christopher Clavius (°1537-†1612). 21 Like all missionary Orders in the sixteenth century, the Jesuits were concerned that their converts might misinterpret Christian images and worship them just as they had worshipped their idols. Ricci's intention, therefore, was to employ drawings and paintings only as a liturgical means of conveying Christian messages, especially to these literati unable to understand verbal expression of Divine meaning. Ricci's aim was to convince the Chinese that Christ was indeed the 'living' God through the perspectival 'realism' of such drawings as those in Nadal's book, and to provide the new converts with 'given' images thus achieving a liturgical meaning for God. Unfortunately, Ricci not being an artist, was incompetent to demonstrate Renaissance perspective and chiaroscuro, nor was he able to present the discovery of disegno from the recently founded Academies of Florence and Bologna.

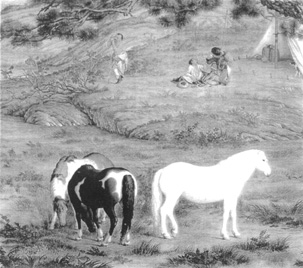

After completing his noviciate at the Jesuit monastery at Coimbra, Giuseppe Castiglione (°1688-†1766) sailed on a Portuguese ship, tracing Matteo Ricci's footsteps, and arrived in Macao in July 1715, the fifty-fourth year of Kangxi'sreign(r.1662-†1722). Four months later, Castiglione was presented to the Kangxi Emperor, under the aegis of Fr. Matteo Ripa (°1682-†1745) whose knowledge of Chinese enabled him to act as a Court interpreter and painter. 22 Castiglione was immediately employed as a Court painter to work alongside Chinese painters and was given the Chinese name, Lang Shining. No Jesuit in China could articulate the Western science of Art as effective as Castiglione, a disciple of Andrea Pozzo. Being employed in the Court, Castiglione secured a privileged position to demonstrate the idea of disegno and to incorporate techniques of perspective and chiaroscuro into Chinese painting. During Yongzheng's reign, Castiglione assisted Nianxiyao, Superintendent of Customs and Director of the Jingdejan Porcelain Kilns, to adapt Andrea Pozzo's Treatise Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum into Chinese with the title of Shishu (Visual Techniques). This Chinese Treatise was first published in 1729 and reissued in 1735. Nianxiyao stated in his preface to the Shishu that he studied the subtleties of European Painting, especially those of creating the illusion of three dimensions by shadows, under the guidance of Lang Shining. 23

Andrea Pozzo:

The Glory of St. Ignatius (1688-1694), nave vault, S. Ignazio, Rome.

Andrea Pozzo:

The Glory of St. Ignatius (1688-1694), nave vault, S. Ignazio, Rome.

Before Castiglione's presence in Court, no Chinese painter employed the chiaroscuro method in painting, nor did they attempt to present any perspectival effects similiar to those of Renaissance perspective. One of many differences between Chinese and European paintings lies in the conceptual understanding of line and its functions in representation. Through appropriating line as a conceptual apparatus, the development of disegno had provided Renaissance perspective and chiaroscuro with a scientific foundation to separate line as an irreducible element of geometrical construction from an essential form of pictorial representation. Although the techniques of Chinese traditional painting are based primarily on lines, this linear technique is integrated with calligraphy within which lines are essential forms of pictorial representation. Both Chinese painting and calligraphy elaborate on the 'strength' of brush work and its variations of line-forms. To the Chinese, permeated by Daoist teaching, the term 'still-life' has no meaning. To them there are no inanimate objects (including lines); everything has its vitality and spirit, qilian which must be made to 'resound' in painting. In Chinese painting, the function of lines does not illustrate the same conceptual representation as they do in Renaissance realism or Baroque naturalism. Armed with the sciences of mathematics and physics, the Western painter followed linear perspective, observed chiaroscuro, sought to draw buildings in accordance with architectonics and strove for anatomic accuracy in portraying human figures. In contrast, the creative process of Chinese painting corresponds with the literary mind of the literati.

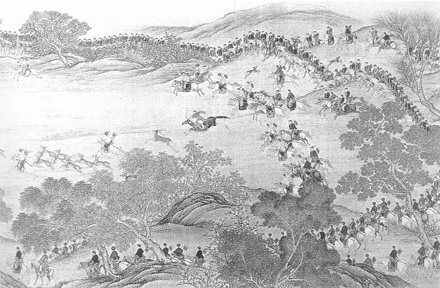

Giuseppe Castiglione: One-hundred Horses - detail.

Painting on silk. 94.5 cm x 776.2 cm. National Museum, Taibei. This masterpiece is a good example of the use of chiaroscuro - an unsual technique in China - to create depth of field via the depiction of shadows.

When the Jesuits first presented their Western style paintings to the Emperor, he and his courtiers all admired the theatrical effect of perspective shown in those works. 24 But the Qianglong Emperor, of a later time, did not appreciate Western techniques. He ordered Castiglione to learn Chinese painting techniques and, eventually, Castiglione developed a totally novel style. And so, to satisfy the Imperial demands, Castiglione added some Chinese techniques of line-work to his Western representation of objects and ideas through the Art of disegno, perspectival effects and chiaroscuro. 25 In Qianglong's Court, Castiglione' s artistic performance was more that of an illustrator than an artist. His talent and knowledge of painting was directed to documenting historical events such as the battles in Upper Asia, Kashgaria, Turkkestan, Zungaria (in 1759 under the name of Sinkiang or New Territory), and the Emperor's ceremonies such as the famous Mulan scrolls, recording the Emperor's annual hunting event. 26 Nevertheless, before Castiglione, the Jesuits could not effectively articulate the idea of disegno as the foundation for representation in art. Although religious illustrations were first brought to China by Ricci, no Jesuit was as talented a painter as Castiglione in being able to demonstrate the idea of disegno as a theory of perspective geometry in painting. Through his sophisticated techniques of perspective and based on Pozzo's Treatises, Castiglione confronted the Chinese conception of pictorial representation by introducing the science of Art through his religious understanding of disegno.

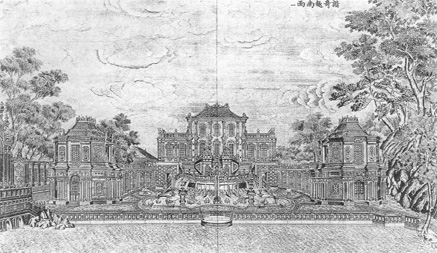

As an architect, Castiglione was an effective agent of Baroque architecture in the construction of the European section of the Yuanmingyuan(Garden of Perfect Clarity), built from 1747 to 1760. It is interesting to note why the role of architect fell to Castiglione who was known above all as a painter and draftsman. The Emperor assumed that Castiglione possessed the same abilities of traditional Chinese literati who were equipped with an impeccable knowledge of science, Art, humanity, and engineering, and were capable of construing and constructing the Emperor's imagination into tangible form. To assist them in this work, the Jesuits sent away to Europe for a certain number of works on architecture, among them Le premier volume des plus excellents batiments de France (1576-1579) by Jacques Androuet Du Cerceau (° 1520-†ca 1584), three versions (Latin, French and Italian) of Vitruvius' De Architectura and Treatises on construction. 27

Giuseppe Castiglione: Qianglong hunting deers, in the Mulan fourth scroll - detail.

Painting on silk. 77.0 cm x 270.0 cm. Musée Guimet, Paris

The Yuanmingyuan's European style Pavilions were begun, in 1747, after drawings by Castiglione, whose knowledge of the Art of disegno and idea of perspectival geometry fundamentally acted for the positioning of allegorical figures and devices in, of and among the buildings so to obtain every possible perspectival effect. 28 The designs submitted to the Emperor by Castiglione were of a fascinating Baroque. As far as one may judge from the ruins and the decorative fragments from the Pavilions which still may be seen at Yuanmingyuan and in some Beijing gardens, Castiglione might have drawn his main inspiration from Italian mature Baroque architecture. Some of the façades with their curving lines and their enormous volutes over the doorways and windows remind one of Borromini's architectural vocabulary and decorative devices, others of Genovese palazzi from the late sixteenth century. 29 Althought the French influence is, on the whole, directly less apparent in the external appearance of the pavilions, the sources of the gardens' landscape design are clearly evident in reference to the park of Versailles. 30 The Pavilions most difficult construction procedure was the installation of theatrical machinery and more specifically, that activating the exuberant waterworks displays. Castiglione had to rely on Michel Benoist (° 1715-† 1774) to engineer the mechanics of the hidraulic works for Qianlong called for palaces "in the manner of the European barbarians"31 in the midst of a multitude of jets of water, cascades and fountains.

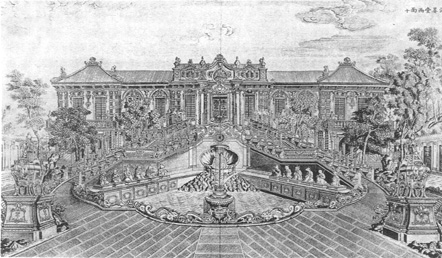

The Xieqiqu (Pavilion of Delight and Harmony), in the Yuanmingyuan.

One of a Collection of eighteen century Engravings. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris

The Yuanmingyuan garden complex comprised three major precincts. In the first stood the Xieqiqu (Pavilion of Delight and Harmony). This building "would bear comparison with the châteaux of Versailles and Saint-Cloud".32 All of marble and majolica, with Corinthian motifs, its central edifice was linked by two symmetrical glazed galleries to two smaller flanking pavilions, intended for musicians. But what most enchanted the Emperor was the complex of fountains. From his window, seated on his throne and surrounded by his concubines, the Emperor could contemplate jets of water spat out by bronze sheep and wild geese. A bridge over pools led to the second precinct where there was a maze and a central kiosk, all of marble. This European maze was called the Huayuanmen (Garden Gate). On the day of the Feast of Lanterns the Emperor held a lantern race for the young girls of his Court. Each of them carried a yellow-silk-lantern with a lit candle attached to its tip; the first to reach the kiosk receiving a gift from the Emperor. In the center of the complex rose the Hayuangtang (Pavilion of the Calm Sea), so-called on account of its vast water reservoir strategically placed on a raised terrace so as to feed a number of fountains and cascades. The architecture of this building, despite numerous Italian Baroque details, was recognizably inspired by the Versailles Palace cour d' honneur and its Trianon de Porcelaine(Porcelain Pavilion) which, ironically, was regarded in Europe as a "Chinese style" folly. 33 Qianlong particularly prized the extraordinary water-clock decorating the foot of the Hayuangtang's facade monumental staircase. Indeed, it was Benoist¨s major hydraulic's tour de force: Twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac: a rat, a bull, a tiger, a hare, a dragon, a snake, a horse, a goat, a monkey, a cock, a dog, and a boar spat out water, one after the other, in turn, for an hour. At midday alone, the water spurted from all the animals mouths.

Castiglione also built other ancillary pavilions, such as the Hushuilou (Pavilion of Gathering Waters), which concealed yet another hydraulic automata. The elevations of the Yangquelong (Sparrows Aviary) were covered with paintings of boats and pheasants and here the Emperor's peacocks and other rare and precious birds were reared. For this building, Castiglione designed a wrought-iron door with a jigsaw pattern cast in wrought-iron greatly appreciated by the Emperor.

"A place is created by natural spirits and treasured by Heaven which provides a space for [the] King to wander and to rest."34 - these were the words that the Qianlong Emperor wrote in praise of the Yuangmingyuan's Western style garden and pavilions, thus surmising their extreme beauty. It is obvious that everything in these buildings demonstrated a deep admiration for theatrical effects, particularly the architectural motifs devoided of all functionality blending with a Baroque profusion of superfluous ornaments. The pavilions proliferation of colours recalled certain Italian or Portuguese palaces, but their roofs, covered with yellow, blue or green tiles complied with the Chinese tradition. Composite as it was, the total effect, a hybrid Chinese Baroque, was nonetheless elegant. It was impossible, as the Jesuits put it, not to "admire the art with which this irregularity was carried out".35

The Hayuangtang (Pavilion of the Calm Sea), in the Yuanmingyuan.

One of a Collection of eighteen century Engravings. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

In 1860, when the Franco-British troops, led by General Cousin-Montauban and Lord Elgin, pillaged the Imperial Summer Palace, North of Beijing, the soldiers found a profusion of jewels, gold snuff boxes, porcelain dishes, table-services and sumptuous costumes in which they dressed themselves. It was a wild masquerade. The soldiers enjoyed, taking extreme delight, the remarkable collections of automata which the Chinese emperors had received from Western sovereigns. "The second night we spent in the Summer Palace was impossible, crazy, giddy," the Count d'Herisson wrote in his diary. "Every trooper had his bird, his music box, his alarm clock and his rabbit [...] Everywhere bells were ringing."36 The pillage lasted two days and ended with a fire. The delirious soldiery tore down tapestries threaded with silver to try to put out the blaze.

The extraordinary Summer Palace of the Emperors of China with their curious toys, mechanicalmonkeys, automata-dancers and cymbal-playing rabbits, went up in flames, while the singing birds warbled madly in their golden cages. [...] A unique testimony of the Yuanmingyuan's past magnificence are twenty copper-plates made, in 1786 by Imperial command, by two pupils of Castiglione.

On the 5th of August 1774 news reached China of the arrest and imprisonment of the Jesuits Father General, Fr. Laurent de Ricci and the Papal proclamation of the dissolution of the Society of Jesus. Foreign missionaries were never to regain the privileged positions the Jesuits had formerly enjoyed at the Imperial Court. During the following century the Europeans employed very different methods to impose their will: the cannon took the place of the sermon.

§5. EPILOGUE

Historians repeatedly raise the issue: What has the West really contributed to the Civilization of the East, especially China, in the last three centuries? Joseph Needham noted in Science and Civilization in China that the Jesuits brought Four engineering Principles, to China: (1) the screw in the form of the Archimedean water-raiser, (2) the Ctesibian double force-pump for liquids, (3) the crankshaft and (4) the clockworks. 37 In The Heritage of Giotto's Geometry, Samuel Y. Edgerton contended that the Jesuits introduced to the Chinese the Renaissance linear perspective and Baroque chiaroscuro, which had largely contributed, in Europe, to democratize the progress of trade skills and technical knowledge. 38 In fact, Needham and Edgerton's approaches to the same issue share a common ground, in that, the visible realms of technology and science became both an important contrast and connection between the West and the East.

Their differences reflect the anthropocentric development of architectural thinking and its practices in the West, specifically recognizing the power of drawing as an epistemological process. Regardless of metaphysical debates between Aristotelianism and Platonism, the West was able to depict the conceptual in the domain of the perceptual and to transform the invisible into the realm of the visible, through the procedures of drawing developed by architectural thinking. In the case of machinery invention, drawing realized the formation of ideas through experimentation. For instance, Francesco di Giorgio Martini's (° 1439-† 1501) Treatises, containing drawings of experimental machines (at one time owned by Leonardo), had become in the seventeenth century one of the most influential engineering books in all Western Europe. The Jesuits brought Martini's ideas, in drawings, to China.

Through a drawn rendering, an object and its parts can be defined by spatial sequences, controlled by geometrical parameters and measured by projective scales. Without the invention of drawing, Needham's Four Principles would have had conceptual and perceptual difficulties to achieve further technical invention and advancement. Without the science of drawing, disegno, linear perspective and chiaroscuro might only produce 'realistic' effects and would not be as influential as Edgerton proclaimed. Without the construction of the European complex of the Yuanmingyuan, the science and Art of disegno might not have been seeded the soil of China. With the 'luck' of historical coincidence, the Jesuits were able to foster worldwide the Baroque development of architectural thinking, and the idea of disegno as the foundation of Arts and more specifically, to promote these in China as theological and scientific imports.

How does Macao testify to a history of Oriental and Occidental connections? I contend that Macao has been a "Baroque theater of the World." Portugal's maritime expansion transported the agents of Baroque thinking to the Orient- the Jesuits - where they conceptualized the World as a Divine system displayed, visualized and manifested through the architectural Orders. Jesuit history alludes to the belief that architecture was once viewed as both a practise and a discipline of inquiry into multiple modes of thinking. Vitruvius' Ten Books on Architecture are the ultimate source for the renewed scripts of this 'drama'. The Jesuits assumed that architecture expressed the 'language' by which God first 'inscribed' His natural laws of the Universe. History becomes present when architecture enacts its imagination. As the first and last European settlement in the East, Macao has grown as a City of exchanges and will continue to foster a fecund exchange of ideas. The enframing proscenium of the St. Paul's Church façade remains as a constant reminder of an incomplete episode of enduring Occidental and Oriental connections.

CHINESE GLOSSARY

qiyun 氣韻

Xieqiqu 諧奇趣

Huayuanmen 花園門

Haiyantang 海晏堂

Huishilou 畜水樓

Jingdezheng 景德鎭

Lang Shining 朗世寧

Mulan 木蘭

Nian Xiyao 年希堯

Shishu 視術

Yuanmingyuan 圓明園

Yangquelong 養雀籠

NOTES

1 TEIXEIRA, Manuel, The Church in Macau, in: Ed. CREMER, Rolf, Macau: City of Commerce and Culture, Hong Kong, UEA Press, 1987, p.43.

2 GOMBRICH, Ernst H., The Story of Art, London, Phaidon Press, 1950, p.290.

3 NICOLAS, Antonio T. de, Ignatius de Loyola: Power of Imagining, Albany, State University of New York, 1986, p. 116 - For a hermeneutic of St. Ignatius of Loyola using a new translation of his Spiritual Exercises, his Spiritual Diary, his Autobiography and some of his letters.

4 Ibidem., p.125.

5 TAYLOR, René, Hermetism and Mystical Architecture in the Society of Jesus, in: Ed. WITTKOWER, Rudolf - JAFFE, Irma B., "Baroque Art: The Jesuit Contribution", New York, NY University Press, 1972, pp.63-97 - For a full discussion.

See: YATES, Frances A., Medieval Memory and the Formation of Imagery, Chicago, Chicago University Press, pp.82-104.

6 CALVINO, Italo, Visibility, Cambridge, Massachussets, Harvard University Press, 1988, p.86.

7 SPENCE, Jonathan, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, New York, Viking, 1984, pp.62-63 - For a discussion on Ricci's use of Nadal's book and his construction on the "memory theatre", in China.

8 WITTKOWER, Rudolf, Problems of the Theme, in: Ed. WITTKOWER Rudolf - JAFFE, Irma B., "Baroque Art: The Jesuit Contribution", New York, NY University Press, 1972, pp. 1-15.

9 ALPERS, Sveltana, The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1983, pp.26-71.

10 LAWRENSON, Thomas Edward, The French Stage and Playhouse in the XVIIth Century: A Study in the Advent of the Italian Order, New York, AMS Press, 1986, p. 178; KEMP, Martin, The Science of Art: Optical Themes in Western Art from Brunelleschi to Seurat, New Haven, Yale University Press, 1990, p. 122.

11 POZZO, Andrea, Perspective in Architecture and Painting, New York, Dover, 1989 [An unabridged reprint of the English-and-Latin edition of the 1693 Perspectiva Pictorum et Architectorum ].

12 KEMP, Martin, op. cit., p.139.

13 KRISTELLER, Paul Oskar, Renaissance Thought and the Arts, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1990, p. 182.

The common understanding of disegno was referred to as the 'science' of Art in drawing; not to be confused with the English term 'design' of the late eighteenth century. The Design- cum -Art Academies followed the pattern of the literary Academies that had been existence for some time, and replaced the older workshop tradition with a regular kind of instruction that included such scientific subjects as geometry and anatomy.

14 SUMMERS, David, The Judgment of Sense: Rennaisance Naturalism and the Rise of Aesthetics, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press,1987.

15 MUNDY, E. James, Ren aissance into Baroque: Italian master drawings by the Zuccari, 1550-1600, Milwaukee, Milwaukee Art Museum, 1989, p.9 - Unlike his brother Taddeo; "one feels that Federico's approach to his art was the conceptual one of an intellectual and a theorist: that painting and drawing were not for him a natural and inevitable means of expression, but his starting-point was an abstract idea around which, so to speak, he drew a line."

16 SUMMERS, David, op. cit., p.300.

17 Ibidem., p.285.

18 Ibidem., p.299.

19 SPENCE, Jonathan, op. cit. - For a discussion of the early Jesuits in the China mission.

20 BOXER, Charles, Jesuits at the Court of Peking, in: "History Today", (41) May 1991, pp.41-47 - For a summary.

21 Clavius was the first to accept the telescope as a scientific instrument and stressed that its revelations could no longer be ignored. The course of the struggle between geocentric and heliocentric cosmologies was changed irrevocably by the advent of the telescope. In 1574, Clavius analyzed and translated Euclid's Elements of Geometry into Latin. An eminent mathematician at the Jesuit Collegio della Propaganda Fide, in Rome, Clavius was asked to validate Galileo's claims. He was also responsible for the reformation of the Calendar, named in honour of Pope Gregorio XIII, which went into effect in Europe, in 1582.

22 Matteo Ripa, an Italian Jesuit who arrived in China, in 1708, later settled at the Court of the Emperor Kangxi, in Beijing. In 1713, he was summoned to the Emperor's Summer Palace, at Jehol, to execute thirty-six engravings of this Imperial estate. His meticulous record of the Imperial property's lavish gardens and huge landscaped grounds, arrived at a most opportune moment in the West, contributing for the advent of the the European "Chinese style."

In 1732, upon his return to his hometown, Ripa founded a College for Chinese, the Collegio de' Cinese, in Naples.

See: CONNER, Patrick, Oriental Architecture in the West, London, Thames and Hudson, 1979, p.42 By 1743, in Beijing, there twenty-two Jesuits, ten Frenchmen and twelve Portuguese, Italians and Germans. Seven of these twenty-two Jesuits were employed exclusively in the service of the Emperor, the others being associated the Court's activities.

See: BEURDELEY, Cécile and Michel, Giuseppe Castiglione: A Jesuit Painter at the Court of the Chinese Emperor, Rutland, Charles E. Tuttle, 1971, p.45.

23 Ibidem., p.37.

24 Catholicism took root in China for the first time during the late Ming Dynasty. In 1600 (Wanli: 28), Matteo Ricci offered a memorial to the Emperor, accompanied by various Christian gifts, including pictures of Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary. These were the earliest 'modern' Western paintings to appear in the Imperial Court of China. A chinese record of these paintings states that: "[...] the faces and draperies [of the depicted protagonists] look like mirrored reflections; the images seem to be able to move as if alive; the highly representational effect is far beyond a Chinese painter's capacity [...]". While in contemporary eighteenth century Western painting, the use of perspectival techniques and chiaroscuro emphasise the outward volumetric appearance of the represented 'reality', Chinese painting traditional techniques tended to elaborate the 'resonance' and 'inner spirit' of what is being depicted.

25 LOEHR, George Robert, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766): Pittore di Corte di Ch'ien-lung, Imperatore della Cina, Roma, Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1940, pp.37-8.

26 BEURDELEY, Cécile and Michel, op. cit., p. 152 - The authors transcribe an exerpt from the 16th of May 1969, "Daily Mail" quoting part of a lecture delivered by Archbp. Lo Kuang, on the occasion of an exhibition of Castiglione's paintings:

"The horses and the flowers painted by Giuseppe Castiglione are exactly like what they are in reality: it is a photograph and that is all; there is neither the spirit nor the rhythm of Chinese painting [...] If he studied Chinese painting it was so facilitate the propagation of his religion and that is praiseworthy. Although he remained in Peking for fifty years, he never learned to write Chinese. That is why the images of the Saints which he painted for the Churches of Peking and its suburbs were not signed by him. The signatures they bear in Chinese characters are not by his hand. His painting has not influenced Chinese painting."

27 Ibidem., pp.66-67; LOEHR, George Robert, op. cit., p.78.

28 ADAM, Maurice, Yuen Ming Yuen: L' oeuvre Architecturale des Anciens Jesuites au XVIII Siècle, Pei-ping, Imprimerie des Lazaristes, 1936 - For a description of these perspectival devices.

29 SIRÉN, Osvald, The Imperial Palaces of Peking, New York, AMS Press [reprint of: Paris, G. van Oest, 1926], 1976, p.47.

30 LOEHR, George Robert, op. cit., p.86.

31 Michel Benoist studied astronomy in Paris. He designed and constructed the hydraulic machines and fountains at the Yuanmingyuan. He died in Beijing, in 1774, after learning of the supression of the Society of Jesus.

32 BEURDELEY, Cécile and Michel, op. cit., p.68.

33 In 1670, it appeared, as if by magic, the first building of a new kind in Europe; a small pavilion in the "Chinese style": the Trianon de Porcelaine. This folly was built by King Louis XIV of France, in the gardens of the new vast grounds he had recently aquired, adjacent to little village of Trianon, to the Northwest of his Palace, at Versailles. In 1687, the Pavilion de Porcelaine was pulled down because it had become too small to hold the lavish Court parties. Althought the Pavilion was modeled after the Pagoda of Porcelain, in Nanjing (known in Europe through Nieuhoff's illustrations), the engravings which visually record its presence, do not testify for a Chinese structure.

See: RYKWERT, Joseph, The First Moderns: The Architects of the Eighteenth Century, Cambridge/Massachussets, MIT Press, 1980, pp. 19-22.

34 Collected Works of Giuseppe Castiglione, Taipei, National Palace Museum 1983, p. 12.

35 BEURDELEY, Cécile and Michel, op. cit., p.74.

36 Idem.

37 NEEDHAM, Joseph, Science and Civilization in China, 7 vols. [to follow], Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1954-1995; 1954, vol.1, pp.241-243

38 EDGERTON, Samuel Y., The Heritage of Giotto's Geometry, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991.

* Researcher on the Architectural Manifestation of Historical Consciousness and in techné in the Art of Making. Ph. D in Architecture from the Institute of Technology, Georgia. Lecturer in the Department of Architecture at the State University of New York, Buffalo. Fellow of the World Academy of Art and Science. The essay presented in this edition is part of his current interest in the Cultural Invention of Baroque.

start p. 185

end p.