[INTRODUCTION]

The Dominican, Friar Domingo Fernández Navarrete [°1618-†1686] left Spain on route to the Philippines in 1646, reaching that far off archipelago in the Far East about two years later. After a long period of intense missionary activity, he departed from Manila in 1657 on his way back to Europe. However unforeseen incidents on their course led them to Makasar [presently Ujung Pandang] in the Celebes [presently Sulawesi] where, at that time, a prosperous Portuguese trading community existed which had inherited part of Malacca's [presently Melaka] trade after it had been conquered by the Dutch in 1641. Fernández Navarrete set off in a Portuguese ship which was heading towards Macao with an important contingent of Jesuits on board. Once they arrived at the Chinese coast, the Spanish Friar decided to join a small Dominican mission which was established in Fu'an,• in Fujian• province. He stayed on there until 1664 which was the time when the Imperial authorities unleashed one of the cycles of persecution against Catholicism. Fernández Navarrete then became part of a group of Dominicans and Jesuits who were detained in Guangzhou• for several years, finally managing to return to Macao in 1670. From there he set off again on his travels inboard Portuguese ships, this time en route to India, and eventually ended up arriving in Lisbon in March of 1672.

After a visit to Rome, to make the High Pontifice aware of the missionary situation in China, Fernández Navarrete settled in Madrid, devoting his time to the writing of a long collection of texts on China and missionaries' activities in that vast Empire. In 1676 he published the Tratados Historicos, Politicos, Ethicos, y Religiosos de la Monarchia de China [...] (The Travels and Controversies [...]), in the Spanish capital. It was a voluminous compendium based on his Asian experiences, and also on notes which he had written down plus different material which he had had access to, including mainly translations of Chinese documents.

Fernández Navarrete's Tratados [...] (Travels and Controversies [...]) would bring to the fore the secret polemics which the Society of Jesus had with other religious orders regarding the methods of missionising used in China, unleashing the famous 'Chinese Rites Controversy'. The Spanish Dominican, based on a wide knowledge of the area, vehemently questioned the legitimacy of adaptations of the 'Rites', and even doctrines, made by the Jesuits active in China mission. Equally the work became a popular compendium of information on China, India and the Celebes, regions which the author had had the opportunity to visit. The accounts on China formed the work's basic nucleus, not only for their great volume and extraordinary conciseness, but also for the fact that Navarrete presented a very positive image of the Chinese Empire, which in many respects was considered as superior to the Catholic powers in Europe at the time. Curiously Fernandez Navarrete's work was never translated into Portuguese in spite of it containing valuable information about Portuguese presence in Macao and in the Far East in general.

28

CHAPTER XVII

Of the City Of Macao, Its Situation, Strength, and Other Particulars

2. The Chineses from all antiquity had prohibited the admitting of Strangers into their Kingdom and Trading with them, tho for some years Covetousness prevailing, they have sail'd to Japan, Manila, Siam, and other parts within the Straits of Sincapura, and of Governador1 in the Sea of Malaca,2 as I have observ'd before: but all this has always been an infringement of their antient Law, the Mandarines of the Coast coniving at it for their private again.{1} This is the reason why when the Portugueses began to sail those Seas and to trade with China they had no safe Port there nor any way to secure one. They were some years in the Island Xan Choang,•3 where St. Francis Xavierius dy'd; some years they went to the Province of Fo Kien,•4 another while to the City Ning Po• in the province of Che Kiang,• whence they were twice expel'd, and the second time ill treated.5 They attempted the place where Macao now stands, but without success; they return'd, and the Mandarines of Canton sending advice to the Emperor, he order'd they should remain there undistrb'd, paying Tribute and Customs for their Merchandize. Thus they settled there, and had continued till my time the term of 130 years.6 Many of the Inhabitants of Macao say that place was given them because having undertaken the task they were then successful in expelling thence certain Robbers, who did much harm to the neighbouring Chineses; and hence they infer that the Place is their own.7 The Chineses, however, disown this claim and so does the Tartar who is now Lord of China.8{2}And if the Grant was upon condition they should pay Tribute and Custom for Merchandize, as they have always done, how are they owners there? At best they are like the Chineses, among whom no Man is absolute Master of a foot of Land.

3. The place is a little neck of Land running off from the Island9 and so small, that including all within the Wall the Chineses have there, it will not make a League in circumference. In this small compass there are Ascents and Descents, Hills and Dales, and all is but Rocks and Sand. Here the Merchants began to build: The first Church and Monastery built there was of our Order, of the Invocation of Our Lady of the Rosary, and the Portugueses still preserve it.10{3} Afterwards there went thither Fathers of the Society of Jesus,11 and of the Orders of St. Francis and St. Augustin. Some Years after they founded a Convent of St. Clare, and carry'd Nuns to it from that of St. Clare in Manila: The Foundation was made without his Majesty's leave and he resented it when it came to his ears; and not without reason, for a Country of Infidels, and so small a footing is not proper for Nuns. That Convent has of late Years been a great trouble to the City. Before I proceed any further, I will here set down what was told me by the Licentiate Cadenas, a grave Priest of that City. When the Tartars conquer'd China, those Nuns fearing lest they might also come over into Macao, and some disaster might befal them, petition'd the City to send them to some other place. Having weigh'd and consider'd the Matter, they answer'd, 'That the Reverend Sisters need not to be in care, for if any thing happen'd, they would presently repair to their Convent with a couple of Bar rels of Gunpowder, and blow them all up, which would deliver hem from any ill Designs of the Tartars." An excellent method of comforting the poor afflicted Creatures.{4}

4. There are in the City five Monasteries, three Parish-Churches, the House and Church of the Misericordia, the Hospital of St. Lazarus, and Jesuit Seminary; one great Fort, and seven little ones.{5} The Plan is very bad, because it was built by piecemeal. It was afterwards made a Bishop's See; the first Bishop was of my Order,12 and till my time no other Proprietor has been consecrated to it.{6} It shall be argued in another place, whether that Lord-Bishop has a Spiritual Jurisdiction over all China, or not; as also whether Tunquin13 and Cochinchina belong to him. At present it is certain they do not, for his Holiness has divided China into three Bishopricks, under whom are Tunqin, Conchinchina, and the Island Hermosa. And tho the Portuguese Resident at Rome oppos'd it, he could not prevail.

5. That City throve so much with the Trade of Japan and Manila that it grew vastly rich, but never would vie with Manila,14 nor is there comparison between the two Citys for all their Analogies. I find as much difference in all respects, betwixt them, as is betwixt Madrid and Vallecas (much the same as between London and Hammersmith) and somewhat more, for the People of Manila are free, and those of Macao slaves [to the Chinese].15

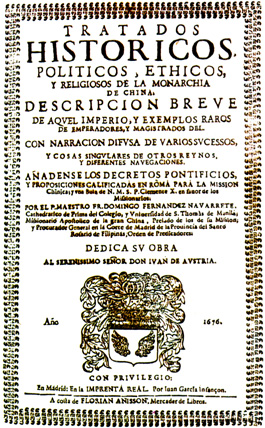

Frontispiece.

In: TRATADOS / HISTORICOS / POLITICOS, ETHICOS,/Y RELIGIOSOS DE LA MONARCHIA DE CHINA. / DESCRIPCION BREVE / DE AQVEL IMPERIO; Y EXEMPLOS RAROS DE EMPERADORES, Y MAGISTRADOS DEL. / CON NARRACION DIFVSA DE VARIOS SVCESSOS, / Y COSAS SINGVLARES DE OTROS REYNOS; / Y DIFERENTES NAVEGACIONES. / AÑADENSE LOS DECRETOS PONTIFICIOS, / Y PROPOSICIONES CALIFICADAS EN ROMA PARA LA MISSION / Chinica; y vna Bula de N. M. S. P. Clemente X, en favor de los / Mi∫sionarios. / POR EL P. MAESTRO FR. DOMINGO FERNANDEZ NAVARRETE, Cathedratico de Prima del Colegio, y Vniuer∫idad de S. Thomas de Manila; / Mi∫sionario Apo∫tolico de la gran China, Prelado de los de Ju Mi∫sion; y Procurador General en la Corte de Madrid de la Prouincia del Santo / Ro∫ario de Filipinas / Orden de Predicadores; DEDICA SV OBRA / AL SERENISSIMO SEÑOR DON IVAN DE AVSTRIA. / AÑO 1676. / CON PRIVILEGIO: / En Madrid: En la IMPRENTA REAL. Por Juan Garcia Infançon. / A co∫∫ta de FLORIAN ANISSON, Mercador de Libros.

Frontispiece.

In: TRATADOS / HISTORICOS / POLITICOS, ETHICOS,/Y RELIGIOSOS DE LA MONARCHIA DE CHINA. / DESCRIPCION BREVE / DE AQVEL IMPERIO; Y EXEMPLOS RAROS DE EMPERADORES, Y MAGISTRADOS DEL. / CON NARRACION DIFVSA DE VARIOS SVCESSOS, / Y COSAS SINGVLARES DE OTROS REYNOS; / Y DIFERENTES NAVEGACIONES. / AÑADENSE LOS DECRETOS PONTIFICIOS, / Y PROPOSICIONES CALIFICADAS EN ROMA PARA LA MISSION / Chinica; y vna Bula de N. M. S. P. Clemente X, en favor de los / Mi∫sionarios. / POR EL P. MAESTRO FR. DOMINGO FERNANDEZ NAVARRETE, Cathedratico de Prima del Colegio, y Vniuer∫idad de S. Thomas de Manila; / Mi∫sionario Apo∫tolico de la gran China, Prelado de los de Ju Mi∫sion; y Procurador General en la Corte de Madrid de la Prouincia del Santo / Ro∫ario de Filipinas / Orden de Predicadores; DEDICA SV OBRA / AL SERENISSIMO SEÑOR DON IVAN DE AVSTRIA. / AÑO 1676. / CON PRIVILEGIO: / En Madrid: En la IMPRENTA REAL. Por Juan Garcia Infançon. / A co∫∫ta de FLORIAN ANISSON, Mercador de Libros.

6. I take it for granted, that what Emanuel Leal da Fonseca, Knight of the Order of Christ, said in my hearing, upon Maunday Thursday [1659] at night, in our Monastery of Macao, is certainly true, 'That the [Spanish] Governor of Manila had more Employments to give than the Portuguese Viceroy at Goa, even before the Dutch had taken so much from them.16{7} It is also certain that his Majesty has more Lands and Subjects in the Philippine Islands, than the Portuguese had sixty Years ago throughout all India. These things are unquestionable.

7. The Trade of Japan failing, Macao began to decay; and that of Manila ceasing, it almost fell to the ground.17 I was told so in that City, and it was visible in the Wants they endur'd. The Monasteries which some Years before maintain'd 24 Religious, in my time with much difficulty and in poverty maintain'd three. So the two Trades of Japan and Manila being at an end, they took up with Sandal of Timor, Ateca18 of Siam, Rosamulla,19 Rota,20 and such-like Commodities, which the Chineses bought, and they took Silks, Calicoes, and other Merchandize in exchange, which they sold at Siam and Macasar21 to the Spaniards by a third hand.{8}

8. Macao ever paid Ground-rent for the Houses and Churches to the Chinese, and Anchorage for Shipping. As soon as any Ship or Pink22 comes into Harbour, a Mandarine presently comes from the Metropolis, and takes the Gage of it, and receives the Duty according to his computation of the Burden.{9} When the Ship goes out, he takes the dimensions again, and receives fresh Custom. Every Year their Measures alter. Is this any think like being absolute Masters of that Place? The Portuguese have lost what territories they had, and would appropriate to themselves what is none of their own.23

9. They complain and alledg in Canton, (nay the Ambassador Emanuel de Saldanha24 said to my face), that our King employ'd all his Stregth in the West-Indies, and suffer'd the East to decline, because it belong'd to Portugal. But I confuted him with my answer, and said, first, If the King of Spain was Lord of Both Indies, and his Grandeur consisted in maintaining his Dominion from East to West, why should he suffer that to decline which he possess'd as absolute Lord and Master? For that would be lessening his own Greatness, which he so much valu'd.

10. Secondly, When Don John de Sylva was Governor of the Philippine Islands, [1609-16] his Majesty order'd all the Force of Manila and Goa should rendezvous at Malaca, and that the Governor and Viceroy should go aboard in Person, in order to fall upon Jacatra, and drive the Dutch quite out of India25 [1616]. Governor de Sylva came with five mighty Ships (and it is well known that one of these Manila Ships can defeat 5 or 6 European Ships); he brought also the best Men in the Islands, Ammunition, Provisions, and all Necessaries. He arriv'd at Malaca, where he awaited Viceroy of Goa two Years, but he is not to come yet! Don John de Sylva went away sad and troubled to Siam, where he was forced to fight furiously some Ships of the Country and Japan. After which he dy'd for grief and disappointment: many more dy'd and the rest returned to Manila, having been at vast Expense. All that ever spoke of this Subject say, that if his Majesty's Orders had been obey'd, the Dutch had infallibly been ruin'd and expell'd India.{10}

11. Thirdly, About the Year 1640, one Meneses, a Gentleman of Goa came to Macao, in his way to Japan, whither he was going Ambassador. He proceeded no further, because of the ill success of another Embassy26 the Year before. This Gentleman talking with Frier Anthony of St. Mary, a Franciscan, of the Power of the Dutch in India, told him, that our King27 had writ into India, to acquaint them that if they thought fit he would send them a strong Fleet, and in it Don Fadrique of Toledo, as Viceroy of Goa, Malaca, and Manila, who would scour the Sea, and make it safe to them to sail from East to West. 'We Portuguese would not accept of what was offer'd for our good," said Meneses, 'and that was the reason we are in such a poor condition. ' And when told this the Ambassador Emanuel de Saldanha answer'd me, 'I did not know all that.'

12. While in Canton upon Midsummer day I was invited with a Portuguese, Father Gouvea, and two others of the Society to visit the Ambassador. The said Father Gouvea28 maliciously insinuating, That the Spanish King could not recover Brasil, and their new King29 [Afonso VI] had done it: The Ambassador said, 'I was a Soldier in that migthy, tho unfortunate, Fleet King Philip the Fourth30 sent out for that purpose. The Portuguese General was Dom Fernao de Mascarenhas,31 Count de la Torre, who was in fault that it was not recover'd.'{11} The Spanish Commander was to keep the Sea, the Count to act ashore, and to that purpose had 13000 chosen Men. The Spanish General offer'd him 3000 Musquetiers of his Men; he several times desir'd the Count to land, and he would secure the Sea, but the Count never durst.' 'It was his fault,' concluded the Ambassador, 'that Brasil was not recover'd.' I was very well pleas'd to hear it, and what is it now they complain of? I often heard it said, that Malaca was lost during our King's Government in the Year 1630. Bento Pereira de Faria the Ambassador's Secretary, said before all Portugueses then at Canton who were in that Error, 'It is not so Fathers, for the Revolt of Portugal was in December 1640, and Malacca was lost the following Year.' I was well pleas'd and consol'd at the Answer.32

13. Discoursing about the loss of Mascate, Emmanuel de Fonseca a worthy Portuguese, told me at Canton. That it had been lost because contrary to our King's Orders they had tolerated a Synagogue of Jews there. Avarice made them permit those infamous People there.{12}

14. At Diu, said the same Man, they allow'd of a moorish Mosque on the same account, and contrary to his Majesty's Commands. Speaking of the Loss of Ceilon [1658] a barefooted Franciscan gave the Account I get down in another Chapter. I afterwards heard it over again, That it was well it was lost, for otherwise Fire must needs have fallen from Heaven, and consumed it all.

15. Talking about some Towns along the Coast, Father Torrente, one of the Jesuits in Canton, said, the Portuguese Commanders us'd horrid Injustice towards the Natives.

16. Upon discourse of the loosing of Ormuz the Jesuit Father Ferrari related, That he being in Malaca, heard some who had been present at the Action, and among them the Enemy's Admiral, say, 'If the Portugueses the day after the Fight had come upon us again, they had certainly catch'd us all, for we were undone, but instead they went off, and left us Conquerors and possess'd of all.'{13}

17. The Portuguese Jesuit Father Antony Gouvea talking at Canton of the loss of India, said‚ God had taken it from them for two Reasons: one was, the inhumane usage of the Natives, especially by the Portuguese Women, towards the Black Women, and the other for their Lust.

18. These and such-like things friar de Angelis might have inserted in his General History; what the Spaniards did in America we know and abhor. It is unreasonable to see the Faults of others, and be blind to our own.

19. We being altogether at Canton, there was some discourse with the Ambassador's Gentlemen concerning the loss of Cochin33 [1663]. The Portuguese Fathers of the Society imputed it to ill Fortune, and to the Natives assisting the Dutch. A Layman who was by took up the business and said, 'Alas, Fathers, we Portuguese are the most barbarous People in the World, we have neither Sense, Reason, nor Government.' He went on with more to this purpose, and concluded, 'They overcame, slew, and took that Country from us, as from base and mean People. The Society was much blam'd for all the other Religious Orders spent all they had to relieve the Soldiers and Townsmen, but the Society not one grain of Rice. The Dutch entred the place, and took all they had.'

20. We talk'd of the miserable condition Macao was in of late Years (I design'd this City for the subject Matter of this Chapter; but because one thing draaws on another, and all tends to make known what I saw and heard in these parts, it is convenient to write all) the Ambassador's Secretary said to Father Gouvea, 'Father, the truth of it is, that Brother [Manoel dos] Reyes, and his Chinese Friend Li Pe Ming, are the cause of the ruin of Macao.' He had not a word to answer. All this has been inserted here, to prove the Portuguese have no reason to complain, that our [Spanish] king was the cause of losing India.34

21. The miserable State and wretched Condition of the Portugueses do now, and have liv'd some Years in those parts, might make them sensible, if Prejudice did not blind them, that their own Sins, and not those of others, have brought all these Misfortunes upon them. They liv'd some Years at Macasar, in great subjection to the Mahometans, neither the Laity nor Clergy had the least Authority,35 so the Governor of the Bishoprick of Malaca who resided there told me, his name was Paul d'Acosta.36 Upon Maunday Thursday [1658], when I was in the Church [in Macassar], a Company of Moors came into the Church, and went up the Sepulcher to see what was in the Monstrance, no body stirring to oppose them.

When they search'd for any Criminal, the Sumbane37 sent five or six thousand Moors, who look'd into the privatest Closet, without sparing any place. They had always to watch at night to secure themselves against the Moors, who stole all they had. They told me above 4,000 Christians had turn'd Mahometans in that Country. When expell'd by the Dutch,38 some of them went over to Camboxa, submittig themselves to such another King, others to Siam, where they live in ill repute, and despis'd by the Natives and Chineses that are there. Some would fain get away from thence, but are not suffered by the King, who says, they are his Slaves; and the reason is, because some Portuguese have borrow'd Mony of the King to trade, and pawn'd their Bodies for it. The King easily lent it them, as it is his Maxim: "That all who in that manner receive his Mony, are his Slaves, and have not the least Liberty left them.'

22. Those Portuguese who liv'd in Cochinchina and Tunqin were expel'd thence. In the Year 1667, this which I shall now relate happen'd in Conchinchina: The Women there being too free and immodest, as soon as any Ship arrives, they presently go aboard to invite the Men; nay, they even make it an Article of Marriage with their own Countrymen, that when Ships come in, they shall be left to their own Will, and have liberty to do what they please. This I was told, and Father Macret who had been a Missioner there affirm'd it to me to be true.{14}A Vessel from Macao came to that Kingdom, and during its stay there, the Portuguese had so openly to do with those Infidel Harlots, that when they were ready to sail, the Women complain'd to the King, that they did not pay them what they own'd them for the use of their Bodys. So the King order'd the vessel should not stir till that Debt was paid. A rare Example given by Christians, and a great help to the conversion of those Infidels! Another time they were so lewd in that Kingdom, that one about the King said to him, 'Sir, we know how to deal with these People, the Dutch are satisfy'd with one Woman, but the Portuguese of Macao are not satisfy'd with many.' Frier de Angelis should note these Virtues of his Countrymen.'{15}

23. Whilst the Government was in the [Ming] Chineses39 the People of Macao own'd themselves their Subjects but now the Tartars rule and so they are, and do confess themselves to be their Subjects. When the City has any business, they go in a Body with Rods in their hands to the Mandarine who resides a League from thence and they petition him on their Knees. The Mandarine in his Answer writes thus: 'This barbarous and brutal People desires such and such a thing, let it be granted,' or 'refus'd them'. Thus they return in great state to the City, and their Fidalgos or Noblemen with the Badg of the Knighthood of the Order of Christ hanging at their Breasts, have gone upon these Errands; and I know one there to this day of the same rank, who was carry'd to Canton, with two Chains about his neck. He was put into Prison, and got off for 6000 Ducats in Silver. If their King knew these things, it is almost incredible that he should allow of them.{16}

24. Ever since the Tartars made the People retire from the Seacoast up the Inland, {in order to free themselves from the incursions of the 'hairy' Chinese - as already described in the first Treatise}40 they began to use rigor with Macao. At a quarter of a League distance from that City, where the narrow part of that neck of Land is, the Chinese many years ago built a Wall from Sea to Sea, in the middle of it is a Gate with a Tower over it, where there is always a Guard so that the People of Macao may not pass across, nor the Chineses to them.{17}41 The Chinese have sometimes had their liberty, but the Portugueses were never permitted to go up the Country. Of late Years the Gate was shut; at first they open'd it every five days, when the Portuguese bought Provisions; afterwards it grew stricter, and was only open'd twice a Month. Then the rich, were but very few, could buy a Fortnights Store; the Poor perish'd, and many have starv'd. Then Orders came again that it should be open'd every five days and the Chineses sell them Provisions at what rate they please.42

25. The Chineses have always liv'd in Macao, they exercise Mechanick Trades, and are in the nature of Factors to the Citizens. They have often gone away with all their Trust. Sometimes the Chinese Government has obliged them to depart Macao, which has much ruin'd that City because many Inhabitants and some Monasteries have nothing of their own, but a few little Houses that the Chineses live in and when they were gone they lost the Rent of them.

26. It would take up much time and paper to write but a small Epitome of the Broils, Uproars, Quarrels and Extravagancies there have been in Macao.{18} Among other things {19}

Among other things our Ennemy [Yang Kuang-hsien]• alleg'd in his Memorials to the Emperor, one was that Father Adam43 had 30,000 Men conceal'd at Macao to invade China. No doubt but it was a great folly. He added, that some twenty years before the City had rais'd Walls, which were demolis'd by the Emperor's Command. This was true. In another Memorial, he accus'd us, that the Europeans resorting to Japan, had attempted to usurp that Kingdom, for which many were punish'd, and the rest banish'd; and that we had possessed our selves of the Philippine Islands. But never any particular King in Europe was mention'd; nor was there any naming of Religious Orders, or Religious. They always made use of the general name of Europe and Europeans.

27. The two [Chinese] Councils of Rites and War, put in a Memorial [to the Emperor] advising it was convenient the People of Macao should return to their own Country. The Government answer'd in the Emperor's name. That since they had liv'd there so many Years, it was not convenient to send them away, but that they should be brought into the Metropolis, for as much as their own Subjects had been drawn from the Sea-coast to the Inland. This was the beginning of much debate and confusion. The [Canton] Mandarines made great Profit from the Inhabitants of Macao, and would not have them change their habitation. At the Court they insisted on what has been said, and order'd a place should be assign'd them to live in. One was appointed near the River of Canton, the worst that possibly could be found. Notice was given to Macao, the City divided into two Factions. The Natives and Mungrels were for going, the Portuguese against it. The Supreme Government beset them by Sea, order'd their Ships to be burnt, accordingly the were burnt before their Faces, and they seiz'd Goods seven had brought the foregoing Year.

28. We at Canton, and they at Macao, were in great confusion, things growing worse and worse every day.{20} The City of Macao promis'sd the Supreme Governour of Canton 20000 Ducats, if he could prevail that they might continue in their City. Self-Interest mov'd him to use all his Power to obtain it, and he obtain'd leave for them to stay, but that they should not trade at Sea. The governour then demanded the promis'd Money but they answer'd they would pay it if he got them leave to trade. This inrag'd the Governour, who became a very Tiger and now endeavour'd to do them all the mischief he could. He shut up the Gate in the Wall, allowing it to be open'd but twice a Month. It pleas'd God, or rather it was his permission, that the Governour, having been at variance with the Petty King, hang'd himself the 9th of January 1668, upon which Macao recover'd some hopes of bettering its condition. {21} Meantime in Canton the business of the Ambassador [Saldanha] was at a stand: he was full of trouble, especially because he had brought by 2800 Pieces of Eight with him, and had above ninety Persons to maintain out of it. 44 Macao could assist him but little, and afterwards excus'd it self from even that. All men complain'd of the Society [of Jesus] which had advis'd and project'd the Embassy. True it is, that this Complaint being made before me those who were in Canton, Fr. John Dominick Gabiani45 a Piemontese answer'd; 'Gentlemen, not all the Society had a hand in this Embassy, only some in particular Persons had; you are not before to condemn the whole Society.' Pereira, the Secretary, who was all fire, reply'd, 'We do not blame the Society in Rome, France and Madrid, but that in China. Your Reverences procur'd this Embassy, as also that Macao should bear the charge of it, the which has ruin'd us; it is for this therefore that the Complaints is made here, and not before the Fathers in Europe.' One of the great griefs of the Portuguese had, was to see and hear how they us'd their Ambassador. They call'd him 'a Mandarine, that was going to pay Tribute and do homage on the part of the Petty King of Portugal'. When he went up to the Imperial City, there was a Flag or Banner upon his Boat, with two large Characters on it, which according to our way of speaking signify'd, 'This Man comes to Homage.'{22} All Ambassadors that go to China must bear with this, or they will not be admitted.

Revised reprint of:

[NAVARRETE, Domingo Fernández de,] The Travels and Controversies of Friar Domingo Navarrete 1618-1686 / Edited from manuscript and printed sources by J. S. Cummins, 2 vols., Cambridge, Hakluyt Society at the University Press, 1962, vol. II, pp. 260-273 [No. CXIX] - vol. I, Cambridge, Published for the Hakluyt Society, second series No. CXVIII (issued for 1960); vol. II, Cambridge, Published for the Hakluyt Society, second series, No. CXIX (Issued for 1960).

For the Portuguese translation see:

NAVARRETE, Doming Fernández, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Tratados Históricos, Politicos, Éticos e Religiosos da Monarquia da China, in "Antologia Documental: Visóes da China na Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 198-204 - For the Portuguese modernised translation by the author of the Spanish (Castilian) original text, with words or expressions in between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese translation, see:

NAVARRETE, Friar Domingo Fernández de, Tratados Historicos, Politicos, Ethicos y Religiosos de la Monarchia de China. Descripcion Breve de Aqvel Imperio, y Exemplos Raros de Emperadores, y Magistrados del. Con Narracion Difvsa de Otros Reynos, y Diferentes Navegaciones. [...], Madrid, Imprenta Real, Por Juan Garcia Infançon, 1676, Tratado [Treatise] 6, pp. 362-368 - Partial translation from Spanish.

NOTES

The numeration of these notes specifically refer to the section of Domingo Navarrete's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 203-204.

The prevailing numeration of these notes is indicated between curly brackets << { } >> and is cross-referenced to J. S. Cummins' English translation [JSC] of Domingo Navarrete's original text, indicated immediately after, in between flat brackets << [ ] >>.

The contents of these notes have been transferred in their entirety exactly as they appear in J. S. Cummins' English translation [JSC] of Domingo Navarrete's text, and do not follow the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

Whenever followed by a superciliary asterix << * >>, these notes' bibliographic references are alphabetically repertoried according to their author's name in this issue's SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY following the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

{1} [JSC, p.260, n. 1] Many of the troubles between Macao and Peking• were the result of scheming and self-interest on the part of the mandarins at Canton, who made a handsome profit out of the official trade-post at Macao; other trading, e. g. with Japan and Java was carried on by Fukienese smugglers. It is this last that Navarrete accuses the mandarins of conniving at.

{2} [JSC, p.261, n.1] For the establishment of Macao, see Boxer, South China‚* xxxv-xxxvii; and for 'fact and fancy in the history of Macao", see Boxer, Fidalgos.*

{3} [JSC, p.261, n.2] For the history of the Dominicans in Macao see: J. M. Braga, 'A Igreja de S. Domingos e os dominicanos em Macau',* BEM, XXXVI (1939), 749-74.

{4} [JSC, p.262, n. 1] For an account of the establishment in Manila of the parent-house of these Franciscan nuns, see Blair,* XXII, 104-107; XXXV, 294-9 and the studies by L. Pérez and F. Lejarza* in Archivo Ibero-americano, XVIII (1922), 225-43; XVI (ns), (1956), 42-60. The nuns in Macao were briskly dismissed by Hamilton* (II, 116) as 'devout Ladies, out of Conceit with the Troubles and Cares of the World.' If Navarrete is right, they had not yet escaped. After Portugal regained her independance from Spain (1640), the Spanish left Macao for Manila; the official order regarding the nuns' transportation to Manila, and commanding all proper treatment for them, is at GOA, Livro dos Regimentos e Instruções,* No. 4, ff. 67-8, dated 6 May 1643. For their subsequent history see A. Meersman, 'The chapter-lists of the Madre de Deus Province in India, 1569-1790',* Studia, No. VI (1960), 165.

{5} [JSC, p.262, n.2] On the Misericordia, 'one of the redeeming figures of Portuguese imperialism in Asia', see Boxer, Fidalgos, 217-20, and also J. C. Soares, Macau e a Assistência; panorama médico-social * (Lisbon, 1950).

{6} [JSC, p.262, n.3] Macao was raised to a Bishopric by Gregory XIII (Super specula militantis Ecclesiae) on 23 January 1576. But the question who was the first Bishop is not as clear as Navarrete suggests. The early history of the diocese is both confused and tempestuous (M. Teixeira, Macau e a sua diocese* (Macao, 1940), II, 55 ff.).

{7} [JSC, p.263, n. 1 ] The Dominican priory of Macao seems to have been a centre of pro-Castilian tendencies (Braga, 755-7).

{8} [JSC, p.263, n.2] 'Ateca' is teak; 'Rosamulla' (anglicè, Rose-mallows) is liquid Storax (Hobson-Jobson‚* 770; Hamilton, II, 122). 'Rota' is rattan (Dalgado,* II, 260; and cf. Hamilton, II, 114; 'They make Bowls, Cups and Tables of Rottans, and cover them very neatly with Lack of divers Colours, and gild them').

{9} [JSC, p.263, n.3] 'The Forts are governed by a Captain-general, and the City by a Burgher, called Procuradore, but, in Reality, both are governed by a Chinese Mandareen, who resides about a League out of the City, at a Place called Casa Branca' (Hamilton, II, 116).

{10} [JSC, p.264, n. 1] Costa* (333-4) gives a more coherent version of this affair.

{11} [JSC, p.265, n.1] Torre's 'sole qualifications appear to have been his aristocratic birth and the fact that nobody else wanted the post' (C. R. Boxer, The Dutch in Brazil * (Oxford, 1957), 89).

{12} [JSC, p.266, n.1] Muscat, the centre of Portuguese power in the Persian Gulf after the loss of Ormus, was lost in January 1650.

{13} [JSC, p.266, n.2] Ormus was captured (1622) by English ships, commanded by Captains Blyth and Weddell (EF‚* 1622-3, vii ff.), acting in conjunction with a Persian army.

{14} [JSC, p.268, n.1] There seems no other authority for the statement that Macret was in Conchinchina; see Pfister,* 368.

{15} [JSC, p.268, n.2] Even discounting Navarrete's nationalistic bias, 'everyone blamed the Portuguese as bringing down the tone of moral life in any place' (S. Asaratnam. 'Some Aspects...',* Tamil Culture, VII (1958), 14), and many other travellers came to the same conclusion: Manucci* (IV, 90) heard in Goa that the Portuguese were a 'small nation of madmen and troublesome fellows' and himself adds 'It seems to me he was largely right.' Carré* (passim) complains of Portuguese 'arrogance, decadence, slothfulness, dissolute lives, meanness, tyranny, jealousy', etc. Tavernier* (I,151-2) complains that the Portuguese were 'no sooner passed the Cape of Good Hope than they all become Gentlemen and add Dom to their names and as they change their status so also change their nature'. Manucci (III, 134) echoes this. See also the Imperial Gazetteer of India (Oxford, 1907-9), XII, 252 ft.

{16} [JSC, p.269, n.1] This is borne out of Hamilton's experience of Macao (II, 118); in the interests of trade the merchants were ready to submit but others were sometimes for resisting (cf. the attitude of the fire-eating Vicar-General of Macao, friar Dos Anjos, as described in Gama's Diary‚* I, 113).

{17} [JSC, p.269, n.2] The 'neck of Land' was a sandbank called the 'Stem of the Water-Lily'; across this the 'Kuan-cha'• wall was built and the Ch'ien-shan fortress erected at Ch'ien-shan• (Casa Branca). After 1664 the garrison was raised to 2,000 soldiers and a strict watch maintained over the passage to Macao (Fu, 'Two Embassies',* 77). A day-to-day account of the situation inside the bockaded city is given in Gama's Diary. See also Rouleau,* 'Siqueira', 28 ff.

{18} [JSC, p.270, n.1] It is hardly surprising that Navarrete's normally fluent pen flinched before this task, for Macao seems to have been in almost perpetual state of anarchy. The English Factor's report of 1649 was not unique: 'the Portugalls in Maccaw... having lately murdered the Captaine Generall... and Maccaw itself soe distracted amongst themselves that they are dailie spilling one anothers blood' (Boxer, Fidalgos, 154). See also A. Marques Pereira, Ephemerides Commemorativas da historia de Macau* (Macao, 1868), 98-9.

{19} [JSC, p.270, n.2] This episode in the history of the Church Militant took place in 1623 and the quarrel arose when the Jesuits refused to recognize the Dominican Vicar-General António do Rosario. It is not certain if the priory was actually bombarded. There is an account in GOA, Ordens Regias* No. 3, ff. 295-300; see also Boxer, Fidalgos, 97, and Teixeira, II, 103-4.

{20} [JSC, p.271, n.1] For an account of the state of Macao at this time, see Boxer, Azia Sinica‚* II, 86-92, and Gama.

{21} [JSC, p.272, n.1] Lu Hsing-tsu,• Viceroy of Liang-kuang,• hanged himself fearing punishment after having been denounced for cruelty by the 'Prince who Pacifies the South', Shang K'o-hsi, • (Fu, Two Embassies', 78). Navarrete gives more detail at T 77 ;* see also Gama, II, 748, and cf. p. cxiv above.

{22} [JSC, p.273, n.1] The two characters are identified (Fu, 'Two Embassies', 83) as cháo-kung• (to pay hommage and present tribute) or as kung-shih• (tributary envoy).

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that of Domingo Navarrete's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 203-204.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics <<“ “ >> - unless the spelling of the original Spanish [Span.] text is indicated - followed by the spelling of J. S. Cummins' English translation [JSC], indicated immediately after, between quotation marks within parentheses <<(" ") >>.

1 “Governador” [Port.] ("Governador"): a non-identified Strait.

2 “[...] mar Malaio., [...]” (lit.: '[...] Sea of Malaysia [...]' or "[...] Sea of Malaca, [...]"): meaning in this context, the southernmost expanse of the South China Sea.

3 "Xan Choang” [original Span.] 'Sanchoão' [Port.] ("Xan Choang") = Shangxhuan Dao• [Chin.]: an island regularly visited by the Portuguese between ca1548-1554.

4 “Foquiem” [Span.] 'Chincheu' [Port.] ("Fo Kien") = Fujian• [Chin.]: in this context, the coast of this province, where Portuguese traded between 1530 and 1549.

5 The Portuguese were expelled from “Liampoo” [Port.: 'Liampó'] in 1548-1549 in the ambit of a vast operation of the Chinese navy aiming at extinguishing piracy along the coast of China.

6 The author visited Macao in 1658 and 1570.

7 (See: Text 10 - João de Escobar)

8 The Qing dynasty (1644-1912), of Manchu ancestry, came to power in 1644, but the instability in southernmost regions of China were only appeased several years later.

9 "[...] daquela ilha [...]" ("[...] the Island [...]"). Although contemporary text usually make reference to the "[...] ilha de Macao [...]" (lit.: "[...] island of Macao [...]") in fact the settlement is situated in a peninsula.

10 The author was a Dominican Friar. The first three Dominicans arrived in Macao in 1587 building in the settlement a small convent, but in 1590 they were compelled to leave the city and surrender the property to the care of Portuguese members of the Order.

11 Fathers of the Society of Jesus were established in Macao since the very first days of the foundation of the settlement.

12 The first effective Bishop of the Diocese of Macao was Dom Melchior Carneiro S. J., (1568-1581), Apostolic Vicar in China and Japan; the second was Dom Leonardo de Sá of the Order of Cister and O. M. C., (1581-†1597), First Tutelary Bishop; the third one being Dom João Pinto da Piedade, a Dominican, (1608-1626), Bishop of Macao, resigned in 1623. The author is most probably making reference to Dom João Pinto da Piedade.

13 “Iunquin” [original Span.] 'Tonquim' [Port.] ("Tunquin"): most probably the kingdom of Tonkin, of present day Vietnam.

14 An opinion certainly not subscribed by all contemporary traders from Macao.

15 A reference to the total dependence of Macao from the authorities of the Guangdong• province, which situation was in contrast to the absolute independence of Manila from the other Eastern Asia powers.

16 This computation of the extent of Spanish domains was not rigorous, and did not include the territories under the jurisprudence of the {Portuguese} State of India stretching from the eastern coast of Africa to Macao.

17 The trade between Macao and Japan definitely ceased in 1639. The Restauration coup in metropolitain Portugal in following year [- making Portugual independant from Spain -] caused a temporary trade decrease between Macao and Manila.

18 "areca" [original Span.], 'areta' or 'areca' [Port.] ("Ateca"), 'areca', 'areca nut' (Lat.: Areca catechu) or 'betel-nut': a nut much used in the composition of 'betel', a chewing mixture of pounced areca-nuts, lime, oyster powder and other aromatic substances roled in a betel leaf, with stimulating and astrigent properties much appreciated in the Far East.

19 "roçamalha" [Port.] ("Rosamulla"): a liquid resin. A kind of medicinal unguent obtain from heating and squeezing the of the Liquidambar orientalis, a tree common in certain regions of the Far East.

20 "rota " [Port.] ("Rota"): a plant from the same species as the palm trees, with which are manufactured ropes, mats, sails and multiple other artifacts.

21 "Macáçar" [Port.] ("Macasar", 'Macassar' or 'Makasar') {presently Ujung Pandang}: an important port in the southern coast of the Celebes Island {presently Sulawesi}, where an important Portuguese community thrived until the second half of the seventeenth century. (See: Text 25, note 13)

22 "patacho[s]" [Port.] ("Pink"): vessel with two or three masts similar in structure to the Portuguese nao [Port.: 'nau']. {sic}

23 The statements of the author must be understood as a criticism to the alledged allegations which he heard from the Macanese regarding Portuguese sovereignty of Macao.

24 Dom Manuel de Saldanha was in charge of the Portuguese embassy (1667-1670) sent to the Chinese Emperor {Kangxi} in Beijing, in an attempt to consolidate the position of the Portuguese in Macao.

25 Don Juan da Silva was Governor of the Philippines, 1609-1616. The Luso-Spanish expedition of 1615 against the Dutch - which had established their Oriental headquarters in Jakarta, in the Island of Java - was conceived in a during during which the Crowns of Portugal and Spain were under the rule of King Felipe II of Spain (Filipe I of Portugal) [°1527-r.1554(S)/r.1580 (P)-†1598]. Dom Jerónimo de Azevedo was at the time Viceroy of the {Portuguese} State of India, 1611-1617.

26 The Portuguese were formally forbidden to trade with Japan in 1639. In an attempt to re-establish the profitable trade between Macao and Japan, Macao sent an embassy to Japan in the following year but the Portuguese envoys and much of their retinue were sumarily executed in Nagasaki by the Japanese authorities.

27 King Felipe IV of Spain (Filipe III of Portugal) [°1605-r. 1621 (P)/r. 1640(S)-†1665) ruled over Portugal during the first nineteen years of his reign.

28 "[...] padre Gouveia [...]" ("[...] Father Gouvea [...]"): Fr. António Gouveia (°1592-†1677), S. J., a religious of the China mission.

29 "[...] novo [monarca]." ("[...] the new King [...]"): King Dom João IV (°1604-r.1640-†1656), of the Braganza dynasty. During the reign of this sovereign the Portuguese once again took full control of the coastal regions of South America and Africa, in both sides of South Atlantic, obliging the Dutch to withdraw from Brazil and Angola.

30 The author is making reference to the armada sent by the Portuguese government to Brazil in 1639, commanded by the Count of Torre and defeated by the Dutch.

31 "[...], fulano Mascarenhas, [...]" [Port.] ("[...] Dom Fernao de Mascarenhas, [...]"): Dom Fernando de Mascarenhas.

32 "Malaca" [Port.] ("Malacca") {presently Melaka} was conquered by the Dutch in 1641. Luso-Spanish resentment was greatly felt in the city at that time.

33 The city of Cochin was conquered by the Dutch in 1664.

34 During the time of the 'Iberian Union' (1580-1640), the Dutch and the English being at war with Spain, intensified their incursions against the Portuguese possessions in the Far East and attempted to cease Portuguese navigation in the seas of the Orient.

35 After the fall of Malacca to the Dutch in 1641, many Portuguese residents and some Catholic missionary Orders moved to Makasar {presently Ujung Pandang}, where they maintained friendly relations with the Muslim rulers, religious discrepancies being relegated to a secondary position in favour of prevailing trade interests.

36 Although residing during that period in Makasar, Fr. Paulo da Costa remained the Governor of the Bishopric of Malacca between 1641 and 1660, when he departed to Macao, Cambodia and {the Portuguese State of } India. The author was in Makasar in 1657-1658 where he most probably met the prelate.

37 "Sumbanco" [Port.] ("Sumbane" or 'Karaeng Sumanna'): one of the ruling princes of Makasar.

38 The Dutch conquered Makasar in 1660.

39 "[...] os chineses [...] " ("[...] the [Ming] Chineses [...]"): during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644).

40 The author is refering to the Imperial Edict of 1662, which determined that in order to estinguish the attacks of Chinese sea pirates, all population living near the coast of China had to abandon their residences and move inland.

41 "[...] uma porta corn uma torre por cima [...]" ("[...] a Gate with a Tower over it, [...]"): the so called 'Portas do Cerco' [Port.] ('Border Gate' or 'Barrier Gate').

42 Although at first the Chinese authorities stubbornly tried to make the Portuguese to comply with the Imperial Edict of 1662, they finally condescended with great reluctance to allow the Portuguese to remain in Macao.

43 The German Johannes Adam Schall von Bell (°1592-†1666), S. J., was one of the eminent Fathers of the China mission. He was to become an intimate friend of the {Shunzi• (r. 1644-†1661) and Kangxi• (r. 1662-†1722)} Emperors of China and was confered with the prestigious position of Director of the Astronomical Bureau, in Beijing.

44 As it frequently happened to most other foreign embassies to the Court of China, that of Dom Manuel de Saldanha was no exception, having to wait in Guangzhou• during several months before proceeding to Beijing.

45 "Giovanni Domenico Gaiati" ("John Dominick Gabiani"): an Italian Jesuit, born in 1593, of which only scant information is available.

*First edition: Madrid, 1676.

start p. 109

end p.