[INTRODUCTION]

Born in Oporto at the end of the sixteenth century, Friar Sebastião Manrique left for the Orient before 1604, for in that year he taught at the convent of the Saint Augustine's Order in Goa. In 1628 he was chosen for the mission which this order supported in the town of Ugulim, in the kingdom of Bengal. This was the beginning of a long pilgrimage around Oriental lands, which took him mainly to Bengal, Arakan, Japan, the Philippines, Cochin-China, Macao, the Celebes [presently Sulawesi] and Orissa. From the Oriental coast of Hindustan, where he stayed in 1640, he decided to continue overland to Europe, continuing a tireless life of adventures, apparently so improper for a man of religion. In 1643, after a long circumnavigation, he arrived in Rome where he remained for several years as a representative of his order, and began the writing of an account of his extensive travels in Asia.

The vast work, Itinerário delas Missiones del India Oriental [...] ([...] the Itinerario de las Missiones Orientales[...]) was first published in Rome in 1649 in Castillian specifically to gain a wider audience. In spite of his formal, heavy style, the work was characterised by the rigour of his geographical, historical and ethnographical digressions which were essentially based on his experiences. He was an attentive observer and interested in the exotic world that he lived in for so many years. However it is likely that the Augustinian missionary had used some other written sources to add to his memoirs, as it is possible to detect in the Itinerario [...] ([...] the Itinerário [...]) some analogies with other contemporary works, namely Fernão Mendes Pinto's Peregrinaçam [...] (The Voyages and Adventures [...]) (1st edition: Lisbon, 1614), which inspired part of the passage transcribed here regarding the founding of Macao. Sebastião Manrique would finally die in 1669 in London, assassinated by one of his servants. The text transcribed here on Macao and the Chinese Empire is little known and rarely cited, perhaps because it came included in a work which apparently had nothing to do with China. This detail, in itself relevant, is combined with the fact that Sebastião Manrique explicitly quotes Chinese historical and geographical works which it is understood he read in Macao. V

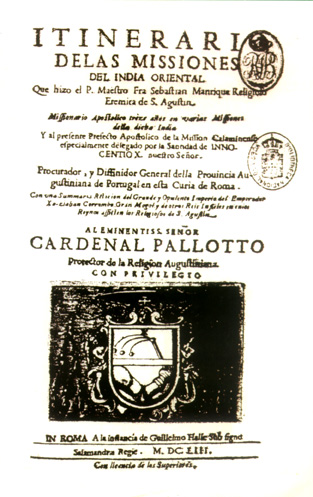

Frontispiece.

ITINERARIO / DELAS MISSIONES / DEL INDIA ORIENTAL / Que hizo el p. Mae∫tro Fra Seba∫tian Manrique Religioso / Eremita de S. Agu∫tin. / Mi∫∫ionario Apo∫tolico treze años en varias Mi∫∫iones / della dicha India / Y al pre∫ente Prefecto Apo∫tolico de la Mi∫∫ion Calaminen∫e / e∫pecialmente delegado por la Sanndad de INNO - / CENTIO X nue∫tro Señor. / Procurador, y Diffinidor General della Prouincia Au- / gu∫tiniana de Portugal en e∫ta Curia de Roma. / Com vna Summari I Relicion del Grande y Opulento Imperio del Emperador / Xs-zisban Carrambo Gran Mongol y de otros Reis Infielos en suios Reynos a∫∫isten los Religio∫os de S. Agu∫tin / AL EMINENTISS. SEÑOR / CARDENAL PALLOTTO / Protector de la Religion Augstiniana. / CON PRIVILEGIO / IN ROMA A la in∫tancia de Guillelmo Flalle Sub ∫ingd / Salamandra Regie. M.DC.IIII. / Con licencia de los Superiores.

Frontispiece.

ITINERARIO / DELAS MISSIONES / DEL INDIA ORIENTAL / Que hizo el p. Mae∫tro Fra Seba∫tian Manrique Religioso / Eremita de S. Agu∫tin. / Mi∫∫ionario Apo∫tolico treze años en varias Mi∫∫iones / della dicha India / Y al pre∫ente Prefecto Apo∫tolico de la Mi∫∫ion Calaminen∫e / e∫pecialmente delegado por la Sanndad de INNO - / CENTIO X nue∫tro Señor. / Procurador, y Diffinidor General della Prouincia Au- / gu∫tiniana de Portugal en e∫ta Curia de Roma. / Com vna Summari I Relicion del Grande y Opulento Imperio del Emperador / Xs-zisban Carrambo Gran Mongol y de otros Reis Infielos en suios Reynos a∫∫isten los Religio∫os de S. Agu∫tin / AL EMINENTISS. SEÑOR / CARDENAL PALLOTTO / Protector de la Religion Augstiniana. / CON PRIVILEGIO / IN ROMA A la in∫tancia de Guillelmo Flalle Sub ∫ingd / Salamandra Regie. M.DC.IIII. / Con licencia de los Superiores.

27

CHAPTER XLVI

How I left the Kingdom of Cochin China for the city of Macan. in the Chinese Empire; with a brief account of it and the early settlments possessed by the Portuguese in it.

[294/1] In spite of the efforts made by the Portuguese to start as soon as possible for Macan• we were unable to leave until May 29 of the same year, namely'39'.1{1}

We sailed in a Junk{2} belonging to a Portuguese from Macan named Diego Cardoso,{3} which was so heavily laden that it stuck at the harbour bar, and we were over six hours bumping on the shoals formed of Caram,2{4} a stone little harder than pumice. Here we stuck until they emptied out [294/2] all the private water-supplies of the passengers, which were kept on the deck, as is usual in such vessels.3 The Junk then floated and we passed over when the tide rose. We made but little way owing to a calm, and we became anxious about our water-supply, which was already short, as they had, as I noted above, destroyed all the private supplies, and the common supply in the tanks was not sufficient for our needs. But our slow progress was what chiefly troubled me, and from our late start there was great fear that we should not [295/1] catch any vessel that monsoon, as they would all have left. Amidst these cares, God our Lord willed that we should reach Macan on the twelfth of June, the day on which the feast of Pentecost fell that year.{5} On arrival I learnt that all the vessels had already left, and so made up my mind to the delay, making the best of what could not be helped. I disembarked with two Priests, who had come to meet me, and went to our Monastery.4{6} Next day I visited the Captain-General, Don Sebastian Lobo de Silveira,5{7} and gave him the dispatches I had brought from the Governor of the Philippines.6 After some talk he pointed out that, since I was obliged to spend the winter there, we should have time to decide which was the best route for me to take. After this reply I talked for some time to him of other matters, and then I returned to the Monastery.

At this time of the year, travel being impossible, I thought it would be out of place, since we had reached Macan, to leave China without giving some account of the city; of its foundation and rise; and of others which the early Portuguese started on this vast and magnificent Empire, of which also I propose to say something.{8}

Although other writers have described this country,7 yet they say so little on the matters I have to deal with, that I trust the Reader [295/2] will not consider me superfluous in also saying something. For I visited that country, sailed along its coasts, saw Macan, the Philippines, and Cochin-China encountering many educated Chinese, some very well acquainted with their own literature and early history.

The first settlement made by the Portuguese in China was Liampo, •{9} two hundred leagues north of Macan,8 which became a rival of the chief cities of India owing to the amount of trade and comerce carried there. But it was destroyed in a revolution in the year of 1542, when Martin Alfonzo de Soza was Viceroy of India9{10} and Rodrigo Vaspereira Marramaque was Captain of Malaca.10{10} Such Portuguese as escaped from the destruction of Liampo went a hundred leagues down the coast to Chincheo, •{11} where they started to found a settlement and carry on commerce and trade.11 They remained here until the year 1555.

The trade moved later to the island of Sanchuan,•{12}six leagues from the City of Canton.•12 and was later transferred to the island of Lampacau,•{12} six leagues from Sanchuan, to the north. Here it remained until the year 1557.

The Portuguese, at the instance of the Queves•13{13}or merchants of the province of Canton and the Viceroy or Tuton•14{14} (as he is called in Chinese), then moved to the island of Macan,15{15} [296/1] where, starting with very small beginnings, they raised a handsome City, beautiful both in its plan and in its buildings, including magnificent churches and splendid private residences.16

This City had a Cathedral Church and a Bishop and other dignitaries, as well as Parish churches. Outside it are several Monastic establishments of mendicant monks, such as Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans, and members of the Company of Jesus, as well as one monastery of the Seraphic Order. The temporal and civil government was as follows: - Under the orders of his Serene Majesty the King of Portugal, a Captain-General, a Chief Justice, and other officers, criminal and civil and revenue, such as are met in Portugal, were appointed. Every one lived as securely as if he was in the centre of Portugal itself. After its foundation the City was many years without any defences or fortifications, as the natives were afraid of the Portuguese, who had armed posts on the island and could thence enter and conquer China.17 But they saw that the Dutch and the English were making attempts to seize the island of Macan,18 and had actually come there for the very purpose in 1622 with a large fleet of big, strong ships.{16} The Portuguese, though few in number, assisted by their slaves, servants, and even their women-folk, resisted every assault most gallantly and killed over eight hundred Dutch with the loss [296/2] of only a few slaves. The Dutch had looked upon the capture of the place as certain, and had quarrelled with the English in their greed and excessive avarice over the partition of the spoil. In their flight they were well jeered, laughed at, and scoffed at by the English, for their overweening confidence.19

The Chinese Governor of the province of Canton, • on considering this event, informed his King of what had taken place and pointed out that the Portuguese were reliable people who concerned themselves only with their business engagements, while the Dutch did not do so, as they were robbers and pirates who infested all the seas and the whole world, and had the Dutch obtained possession of that island they would have been able to ravish and rob those coasts, doing irreparable harm. On receiving this information the Emperor20 gladly gave the Portuguese permission to build walls and fortify the City in any way they liked.

The territories of this great Monarchy are so fertile, and so abound in all that human desire can wish for, in the way of delights, delicacies, wealth, and all that tends to preserve bodily health, that Nature seems to have adorned her by lavishing on these vast regions all the treasures of her wonderful store: in her favoured climate, her equitable temperature; in her air so pure and sweet; in her good policy, riches [297/1] and savour, her ingenuity, vast undertakings, and the strict observance of justice. Above all, the even-handedness of her rule, so just an punctilious, that countries which equal it in other possessions are conspicuously surpassed by it in this, though they may imitate it.

Every one, therefore, who has sufficient knowledge of this country must be at a loss for words to describe the lavishness, liberality, and open-handedness with which the Divine Creator of the world has treated that nation, showering on them the riches, delicacies, and first-fruits of the earth. When I think of this I have often felt deeply distressed to recollect how ungrateful these Barbarians are for such boons from the lavish, all-powerful hand of the Lord.

For they are always offending Him by such a multitude of sins, due to their unreasoning and diabolical idolatry, and their lusts and evil ways. Thus not only is the unmentionable sin permitted publicly in China, but the infernal Priests of their idols and the false Ministers of their religion teach that such practises are great, virtuous, and meritorius acts, and thus they urge them to commit such acts by enumerating particulars and details so detestable as to be unfit for Christian or Catholic ears.21{17}

This favoured and pampered portion of the earth, [297/2] this most coveted part of the known world - I refer to China - lies below the tropic of Cancer with a sea-coast extending, according to the calculations of Chinese Cosmographers, 570 leagues from south to west. On the south it borders on the Kingdom of Cochin-China or Tunqin, and on the west on Grand Tartary, which surrounds most of China: on the east it touches the Kingdom of Botente• (or Catay• as some like to call it).22{18}

The fourth part of China is enclosed by a stupendous wall of immense strength, partly natural and partly artificial.23 I heard read, while I was in China, from the fifth volume of a Special Chronicle on the mighty buildings of that Realm, which deals with this wall, how it is stated that an ancient King, whose name I forget (owing to the loss of my notes on curious things,24 which among other articles were taken from me by the Turks in Damascus at the demand of the Jews, at the Alepo custom-house, whom the Devil himself had brought there on purpose),{19} being harassed by the continuous raids of the Tartar hordes, wished to enclose by a wall{20} the whole frontier which separated the two Kingdoms25 He convoked an assembly, therefore, at Nanquim,• which was attended by the representatives of all the cities, and villages of both States.26 He explained [298/1] his proposal to them, pointing out its utility and security to the Kingdom which would result from its erection. All the assembly agreed to the utility of this work, and the provinces subscribed ten thousand picos of silver,27{21} which are in our currency nearly fifteen million in gold: in addition they sent two hundred and thirty thousand men{22} who were to work regularly until it was completed. Of this great number of workmen thirty thousand were officials and Master-masons. After the materials for this work had been collected, it was carried out with such expedition and care that in twenty-seven years the border between the Chinese Empire and Tartary, from end to end, was shut off by a great lofty wall. According to the book quoted,{23} this stretched over three hundred and twenty-two leagues.28{24} Of this area and number of leagues eighty-one are artificial, filling up places where nature had left gaps, in valleys and passes: the wall was made equal to the mountains in height, even to the most rugged and lofty points.29 In order that the whole wall should be equal and pleasant to look at, the mountains were dressed and shaped from their skirts up, by the plumb-line and set-square, being then plastered over with the same kind of pitch and cement as was on the artificial wall, so that it all seemed to be one and the same.

In the eleventh chapter of the history referred to, the Chinese Author [298/2] says that seven hundred and fifty men worked continuously, of whom the villages of the State provided half of the Ecclesiastical Estates and the Islands of Ainam· the rest. The Emperor, Princes, Nobles, Chaenes,• Tutones,• Aaitaos,•{25} and other Judges and Governors30 also contributed to the second part. And the wall was made so strong that on account of its excellence the Chinese call it Chamfau,• that is, a strong and invincible thing.31

Throughout this great length of wall, of three hundred and twenty-two leagues, there are only five openings which give waterway to the great rivers that flow down from Tartary. These swift-moving torrents start from the ranges and mountains in that country, and after a course of a hundred leagues32{26} pay tribute to the oceans of China and Cochin-China. One of these rivers, and that the largest, known locally as the Batampina,{27}flows out through the kingdom of Sarnau, popularly style Siam, over the Cui bar.33{28} Each of the five openings made in this long wall for the passage of these rivers has two forts upon it, one that of the Grand Emperor of China and the other of the Great Kan• of Tartary,34 each castle standing within the limits [299/1] of their respective states.{29}

According to the Chronicle I have cited, each of the Chinese forts is garrisoned by seven thousand guardsmen, six thousand foot soldiers, and one thousand horse. Most of this force are strangers from various Oriental nations, such as Mogors, Corazanes,35 Persians, Champas,36 and from other neighbouring provinces on the Chinese frontiers.37{30} The Chinese employ these foreign nations because they are themselves a weak and timid race, much given up to inebriation and lust and no lovers of martial exercises.

Along the whole length of this great wall are posted detachments of soldiers, three hundred and twenty in all, each composed of five hundred men, a total of one hundred and sixty thousand [299/2] without reckoning accounts officers, paymasters, commissaries, and other officials and their attendants and guards, besides the catchpolls of the Anchalis39 and Chaenes, who have control over all those people. Added to these was that heterogeneous collection of people which is necessary to serve them.{31}

I might give account of many other matters concerning this great Monarchy, partly from what I have seen and partly from what I have heard read. But they are so extraordinary that I shrink from describing them. But the curious and intelligent Reader can gather from all I have said that a land on which God has so liberally showered the goods of the world will not be lacking in other possessions, so great as to be incomprehensible to the less-favoured people of our Europe.

Revised reprint of:

[MANRIQUE, Sebastião], Travels of Fray Sebastien Manrique 1629-1643 / A Translation of the Itinerario de las Missiones Orientales / with an Introduction and notes by Lt.- Col. C. Eckford Luard, C. I. E., M. A. / Assisted by / Father H. Hosten, S. J., 2 vols., Oxford, Hakluyt Society, vol. II, [China, India, Etc.], pp. 66-76. [No. LXI]~-vol. I, Oxford, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, MCMXXVII, second series, No. LIX (issue for 1926); vol. II, Oxford, Printed for the Hakluyt Society, MCMXXVII, second series, No. LXI (issue for 1927).

For the Portuguese translation see:

MANRIQUE, Fr. Sebastião, LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro., Itinerário das missões da Índia Oriental, in "Antologia Documental: Visões da China n a Literatura Ibérica dos Séculos XVI e XVII", in "Revista de Cultura", Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 191-195 ~- For the Portuguese modernised translation by the author of the Spanish (Castilian) original text, with words or expressions between square brackets added to clarify the meaning.

For the original source of the Portuguese translation, see:

[MANRIQUE, Sebastião], SILVEIRA, Luis ed., Itinerário de Sebastião Manrique, 2 vols., Lisboa, Agência Geral das Colónias, 1946, vol. 2, pp. 143-149 ~- Partial transcription.

NOTES

The numeration of these notes specifically refer to the section of Sebastião Manrique's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 194-195.

The prevailing numeration of these notes is indicated between curly brackets << { } >> and is cross-referenced to E. Luard and H. Hosten's English translation [EL-HH] of Sebastião Manrique's original text, indicated immediately after, in between flat brackets << [ ] >>.

The contents of these notes have been transferred in their entirety exactly as they appear in E. Luard and H. Hosten's English translation [EL-HH] of Sebastião Manrique's text, and do not follow the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

Whenever followed by a superciliary asterix << * >>, these notes' bibliographic references are alphabetically repertoried according to their author's name in this issue's SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY following the standardized formatting of the "Review of Culture".

{1} [HS, p.66, n.1] Sunday, May 29, 1639 (N. S.).

{2} [HS, p.66, n.2] Text as junco. This word junk (from the Malay word ajong, a large ship) is one of the first Indo-European words incorporated into our vocabulary. Friar Odoric uses it in 1331. See Hobson-Jobson,* s. v. Junk; Mundy uses it for "native vessel", ii. 30; see also iii. 203 (illustration); Crawford, Dict, * p.193.

{3} [HS, p.66, n.3] We know nothing more of him.

{4} [HS, p.66, n.4] The word caram has not been traced. Is it the name of the shoal or the kind of rock? The Spanish has martelando sobre unas restingas de Caram que es una piedra poco mas dura que la piedra pomis. It would therefore appear to be the name of the stone. It can scarsely be a mistake for "murram" (Hind.) which means a gravelly soil.

{5} [HS, p.67, n.5] Pentecost or Whit-Sunday. This falls on the seventh Sunday after Easter. June 12, 1639 (N. S.), was a Sunday, and hence Easter must have fallen on April 24 -a very late Easter, as the 25th April is the last possible day.

{6} [HS, p.67, n.6] Careri, who stayed there, remarks that the church was "decently built". The dormitory was unroofed by a storm when he was there (1695).

{7} [HS, p.67, n.7] Mundy* (iii. 327), writing in January 1638, states that at Malacca the "Generall of that citty" (Luiz Martin de Sousa) had visited his ship with "the New Capitaine Generall appointed for Macao who remayned here for lacke of passage". This would, according to Manrique, have been Don Sebastian Lope de Silveira, but we find from Mundy (ibid., pp. 159, 317) that it was Domingo da Camara de Noroña {Noronha [Port.]}, and Lobe de Silveira's signature, moreover, is not on the letter of protest (ibid., p.226). It is difficult to explain this, unless Manrique forgot the governor's name. Silveira was drowned in 1646.

Faria y Sousa, apparently referring to 1638, says that the King of Acheen imprisoned "Francis de Sousa and Castro, who resided there as ambassador" (Stevens, * iii, 411).

{8} [HS, pp. 67-68, n.8] The first Portuguese visited China in 1514, but were not allowed to land. Ferdinand Andrade made a formal visit in 1517, carrying with him Thomaz Pirez as ambassador. Ferdinand Andrade was succeeded by his brother Simon, whose outrageous behaviour provoked the Chinese. The Emperor Kiaht-sing• appointed a commission which adjudged Pirez to be a spy, and he and his companions were imprisoned at Canton• and finally killed in 1523.

The Portuguese next established themselves at Liampo• (Ning-po)• and at Amoy.•

By 1537 their settlements had been started at Sanchuan• Island, Lampacao,• an island north-west of the Ladrones, and also at Macao, tentatively. In 1542 Sanchuan was abandoned, the traders going to Lampacao, which by 1560 had become a large settlement.

The settlement at Macao was started in 1557 under the pretext of erecting sheds for drying goods introduced under the appellation of tribute and alledged to have been damaged in a storm. In 1573 the Chinese erected a barrier wall accross the isthmus between Macao and the island of Hiangshau.• In 1552 Xavier persuaded the Viceroy at Goa to send a second embassy, but the Governor of Malacca stopped it and refused to let it proceed. This is a significant instance of the general discipline in the Portuguese administration. A third embassy came out in 1667, but no results were obtained from it, or from subsequent embassies of 1727 and 1753. It may be added that Macao was never formally ceded to the Portuguese, and even now the relations between the two countries are indefinite. Portuguese authority within the barrier was, however, implied, though not absolutely declared, in the proposed treaty of 1862. But this the Chinese refused to ratify. "

To this day the character of Europeans is represented as that of a race of men intent alone on gains of commercial traffic and regardless altogether of the means of attainment." See Wells-Williams‚ A History of China,* 1897. Their natural suspicions had been increased by a prophecy that a "grey-eyed" people would ruin the Empire (Factory Records,* 1634-6, p.226).

{9} [HS, p.68, n.9] This is Ning-po, situated 29° 49' N., 121° 35' E., in the province of Che-kiang. · about 700 miles from Macao. The outrageous conduct of Lançarote Pereira de Ponte Luna, the Oidor {Ouvidor [Port.]} or chief magistrate, led to an attack by 60,000 Chinese. In four hours the place was destroyed. On hearing of this "one of those whom our vain presumption calls Barbarians [said], 'Let them go on, for they will soon lose as cupidinous merchants what they win as brave soldiers. They now conquer Asia; she will conquer them later on.'" Cf. Faria y Sousa‚* vol. ii, Pt. i, Chap. VIII (Stevens‚* ii. 53), 88; Hobson-Jobson, s. v. Liampo.

{10} [HS, p.68, n.10] Alfonzo de Sousa {Martim Afonso de Sousa [Port.]}was Governor from 1542 to 1545, after a distinguished career as military commander. Of Marramaque nothing is known.

Editor's addendum: Note 10 appears twice in E. Luard and H. Hosten's English translation.

{11} [HS, p.69, n. 11] The survivors of the massacre at Liampo in 1542 wore allowed to settle there in 1547. Chincheo,• as it was then called, is Fukien• province. This name is a corruption of that of the port of Tsaen-chau• or Thisiouan cheou-fou,• or else that of the port of Chang-chau,• south of it and close to Amoy. See Hobson-Jobson, s. v. Chinchew.• Faria y Sousa (op. cit., p.89) says that this settlement "came to naught in 1549", not 1555.

{12} [HS, p.69, n.12] The burial - place of St. Xavier. See Chap. XLIV, n.17. It was known as, and is still called, "St. John's Island" by English sailors. Manrique seems to be wrong in saying Sanchuan was taken over after 1555, as Sanchuan (see note 8) was abandoned in 1542 for Lampacao. See note on p.68.

Editor's addendum: Note 12 appears twice in E. Luard and H. Hosten's English translation.

{13} [HS, p.69, n.13] This is the Chinese word Kan-Pan,• that is, one who attends, a go-between, an interpreter. It appears in Mundy as "Keby". The merchants acted as agents and are therefore so termed (Mundy, iii. 209, n.3).

{14} [HS, p.69, n.14] This is the Chinese word Tu-t'ang• or Kiun-Muen,• which is usually applied to the Governor-General of a province. It is the Cantonese word takt'ang.• See Mundy, iii. p.179, n.4.

{15} [HS, pp. 69-70, n.15] Manrique consistently spells it Macan. The Chinese name is Ngao-man• or "Baygate". But another origin is also given from an idol known as Ama,• Amagau,• or Ama-kan,• and meant the "Harbour of Ama"; this was contracted to Macao (Williams, China,* p.76n.; Hobson-Jobson, s. v. Macao). Mundy, who was at Macao In 1637, gives a brief account of the place (iii. 164, 268). He says that many islands lie round Macao with "high uneven land, no trees, much grass and plenty of water-springs". He says it had many forts and was well provided with ordnance, and the people were well armed. Macao had been fortified against attacks by the Dutch in 1546. The Dutch made various attempts to take it from 1601 onwards, especially in 1622. The buildings faced the sea, half-moon-wise. On a small island called Isla Verde (Green Island) was the Jesuits' settlement. This is now known as Tu-hen-shan• or Patera Island; it forms the western part of the inner harbour of Macao. The Portuguese officials in charge were Captain-General, who controlled the military and forts, and a Procurador, who was the civil authority, together with the Oidor or chief magistrate, a Sergent-mayor or commander of the garrison, an alderman, and a judge. But Hamilton, who was there in 1703, states that the real control lay with a Mandarin at Casa Blanca, a suburb of Macao, of which the Chinese name is Chien-shan.• See Mundy, iii, Index, s. v. 'Macao"; Danvers,* ii. 214, 219.

{16} [HS, p.70, n.16] See Danvers, ii. 214, where an account of this attack is given. He states that 300 Dutch were killed.

{17} [HS, pp. 71-72, n.17] Manrique, without any acknowledgement, has taken this straight out of Mendez Pinto, possibly in part from Mendoza also. The text here is very similar to the Portuguese, and almost absolutely identical with the Spanish version of Pinto (Manrique's variations are given in brackets), "parece que la adorno la naturaleza vertiendo en aquella tierra (en estaso vastissimas provincias) el tesoro de sus muchas (prodigiosas) maravillas. La (enla) apacibilidad del clima (enel) temperamento saludable, la limpieza y suavidad de los aires, la policia, la riqueza, el gusto, los aparatos, la grandeza de sus disposiciones, la grande observacion de la justicia. Sobre todo el govierno tan igual tan justo y cuidadoso que en esta calidad (en esta parte) hace conocidas ventajas a todas las otras partes (naciones) quando en otras olgunas buenas suas otras Provincias o Monarquias (omits these words) la igualen y la imiten" (Pinto,* Chap. XCIX).

The copying continues to the end of the next paragraph, that is to the end of Pinto's chapter. Even the expressions of disgusts are Pinto's.

{18} [HS, p.72, n. 18] Cochin-China and Tonquin are taken as one kingdom here. Grand Tartary is Mongolia in Central Asia; Botente or Catay, that part of Mongolia which lies north of China. See Hobson-Jobson, s. vv. Cochin-China, Cathay.•

{19} [HS, p.72, n.19] See Chap. LXXXVIII.

{20} [HS, pp. 72-73, n.20] Here Manrique again copies from Pinto (Chap. XCI) almost verbatim. The great wall was constructed by the Emperor Chī-Hwangtī• ("Emperor the First") of the Tsin• dynasty. Some walls already existed, and he extended these so as to form a complete barrier from the sea to the great desert. This vast undertaking was completed, seven years after his death, in ten (not twenty-seven) years in B. C.204. It was accomplished, as Manrique says, by co-operation in men and money. It is called the "Wanlī Chang Chin"• or "Myriad mile Wall". It is 1,255 miles long or 1,500 including winding portions; that is, it would reach from Naples to Portugal. It is 15 feet wide at the top (Wells-Williams, The Middle Kingdom‚ * i. 29).

{21} [HS, p.73, n.21 ] Pinto gives a little more information; he says "ten thousand picos of silver, which are in our currency fifteen million in gold at the rate of one thousand five hundred ducats to each pico, as this is the current rate with them."

Yule gives a pecul (pikol), but it is a weight measure; so too in Bowrey (vide Index {Portuguese Lexicon}).

{22} [HS, p.73, n.22] Pinto has "two hundred and fifty thousand men".

{23} [HS, p.73, n.23] Pinto has "in that history". Manrique's Chronicle is imaginary of course.

{24} [HS, p.73, n.24] Pinto has "seventy joas, each joa measuring four and a half leagues of ours, or in all three hundred and fifteen leagues", instead of three hundred and twenty-two. Cogan's* version here, as throughout, paraphrases and omits.

{25} [HS, p.74, n.25] Pinto says: 'by the King, Princes, Lords, Chaenes, Anchalis,• Justices, and Governors". The wall is called Chanfacau in the Portuguese text, Chamfau in the Spanish version and also in Cogan's translation. Manrique inverts the order of certain statements and professes to quote from a specific chapter of a Chinese work; but the text is Pinto's, and is taken from the Spanish version of 1620, which was reprinted in 1627 and 1645, any of which Manrique could have used. The last Spanish edition, that of 1664, appeared after our author's work was issued.

For Tuton• see n.14. Chaenes is the Chinese Chamjan,• who was an assistant military Governor (Mundy, iii. 186, n.2). The following quotation mentions these officials: “All which they promised to solicit with Haitu• (the Lord Treasurer), Champin• (the Admirall of the forces both by land and sea...) For all that tyme both Chadjan,• the supervisor Gennerall and Toutan• or Quan Mone,• the Viceroy were absent farr off” (Ibid., p. 186).

Aaitao is for Hai-tao• or Hoi-tan.• He is clearly a magistrate or similar official. He appears also to have been a naval commander. See: Mundy, iii. 179, n.3.

{26} [HS, p.74, n.26] Pinto has "five hundred", which seems more correct.

{27} [HS, pp. 74-75, n.27] Manrique has deliberately inserted this name, which does not appear in the otherwise practically identical passage in Mendez Pinto. Thus we have, taking the Spanish version:

Pinto: "Solo uno [rio] mas caudaloso y fuerte que los otros va a saler al Reyno de Sarnau (llamado vulgarmente Sian) por la Barra de Cuy" (Chap. XCV).

Manrique: "Uno destos Rios, el mayor, y mas caudaloso a que los naturales llaman Batampina, va salir al Imperio de Sornau a que vulgarmente llaman de Siam, par la barra de Cui" [for Cui see n.28].

But we do find Batampina described by Pinto elsewhere, as he travelled up its full length. Thus (Chap. LXXXVIII) he says: "la ciudad de Nanquim• ... assentada a la largo de la ribera de aquel rio, que ellos llaman Batampina, y en nuestra lengua quiere dezir, Flor de Pescado. Este rio (segun alli me dixeron, y yo vi despues claramente) nace en Tartaria de un gran laguna que se llama Faustir," &c. The Portuguese has "Nanquim... lançada ao longo deste rio, por nome Batampina que na nosso lingua quer dizer• Flor de Peixe'." He then goes on to say that the river "Tanquiday, which name means 'The mother of Waters'... enters the sea in the Empire of Srnmau, popularly called Siam, at the bar of Cuy". Manrique has combined or confused the information in the two passages.

Pinto must refer to the Mekong by his "Tanquiday". He obviously, like Friar Odoric before him, did not clearly distinguish the waters of the rivers he passed up from those of the Great Canal, as he makes this Batimpina go from Nanking• right up to Peking.•

{28} [HS, p.75, n.28] Pinto and Manrique both say this river issues at the "Cui bar" in Siam. The mouths of rivers are called kui or kua in Cambodian.

{29} [HS, p.75, n.29] He follows Pinto, who, however, has after the words "openings made", the additional words, "which I saw". While Manrique inserts in the next paragraph, "According to the Chronicle", Pinto merely says "The Chinese King keeps in each fort..." &c.

{30} [HS, p.75, n.30] The nations Pinto gives differ. He says: "Mogors, Panchus (Pancrus in Cogan), Champas, Corocones, and Guizares of Persia, and from many other lands and Provinces bounding on that great Empire."

{31} [HS, p.76, n.31 ] This paragraph is taken verbatim from Pinto, except that for "catchpolls" (corchetes in Manrique) he has de synonym porquerones.

Anchalis• are the Ngan chah sz',• magistrates or criminal judges.

NOTES

Numeration without punctuation marks follow that of Sebastião Manrique's original text selected in Rui Loureiro's edited text in "Revista de Cultura" (Portuguese edition), Macau, 31 (2) Abril-Junho [April-June] 1997, pp. 194-195.

The spelling of Rui Loureiro's edited text [Port.] is indicated between quotation marks and in italics <<" " >> - unless the spelling of the original Portuguese text is indicated - followed by the spelling of E. Luard and H. Hosten's English translation [EL-HH], indicated immediately after, between quotation marks within parentheses <<(“ ”)>>.

1 "[...] [de Faissó] [...] " [Port.] ("{not translated}") = Haifeng• [Chin.]. After visiting Manila, in the Philippines, the author took residence in "Faissó", in the litoral of the Gulf of Tonkin, in Cochin-China.

2 "carãm" [original Span.] or 'carão' [Port.], ("pearl oyster").

3 Where were probably stored drinking water barrels necessary for all maritime crossings.

4 The residence of the Augustinians in Macao was founded in 1589.

5 Dom Sebastião Lobo da Silveira was Captain-Major of Macao from 1638-1643.

6 During the period ranging from 1580-1640 while Portugal was under Spanish rule it was common the Governor of the Philippines to send messages to Macao. Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera was Governor of the Philippines, 1635-1644.

7 The author might be referring to Friar Gaspar da Cruz' Tratado das Cousas da China [...] (Treatise in which Things of China are related at great length [...]) (See: Text 11 - Gaspar da Cruz) or, more probably, to the narrative of Friar Juan Gonzãlez de Mendonza's Historia De Las Cosas Mas Notables, Ritos Y Costumbres Del gran reYno de La China [...] (The Historie of the Great and Mightie Kingdom of China [...]) (See: Text 16 - Juan Gonzàlez de Mendoza) who also was an Augustinian missionary.

8 The historical realities of the Portuguese establishment of "Liampoo" are still presently debated. The general consensus is that the Portuguese were active between 1540 and 1548 in the foundation of a factory of that name {"desse nome"-sic} in Shuangyu• Island {"ilha" - sic}, which belongs to the Zhoushan• archipelago, offshore from the city of Ningbo.• The destruction of this factory, where merchants from various regions from the Orient usually settled in winter during their trade period, was accomplished in 1458 {sic} [in the ambit of a vast operation of the Chinese navy aiming at extinguishing piracy along the coast of China], commanded by the Viceroy Zhu Wuan.• (See: Text 22, note 1 + Text 28, note 5).

9 Martim Afonso de Sousa (°1500-†ca1570) not only explored the litoral of Brazil during the 1530-1531 famous expedition, but was also at the service of the Portuguese Crown in the Orient during many years, becoming Governor of the {Portuguese} State of India, 1542-1545.

10 Rui Vaz Pereira Marramaque effectively held the post of Captain of Malacca, 1542-1544.

11 Although the Portuguese frequently visited "Chincheu" - the coast of Fujian• province - since 1530 they never founded a permanent factory, settling in provisional encampments in a variety of different deserted islands located along the coast during the trade season. It seems that the Portuguese mercantile activities were transfered to Guangdong• province before 1549.

12 The distance between Shangchuan Dao• [Port.: Sanchoão] and Guangzhou are a mere thirty miles.

13 "queue[s]" [Span.] or "queve[s]" [Port.]("Queue[s]": the big Chinese traders of Guangdong province - according to Portuguese seventeenth century documental and literary sources. A word of controversial etimology possibly deriving from Guanghang• [Chin.].

14 "tutão" [Port.] ("Tuton") = dutang• [Chin.]: the Viceroy or governor general of a Chinese province. (See: Note 30)

15 Although contemporary texts usually make reference to the "[...] ilha de Macau [...]" (lit."[...] island of Macao [...]") in fact the settlement was situated in a peninsula.

16 The author's description coincides with the description of the facts as described by Fernão Mendes Pinto in his Peregrinaçam [...] (The Voyages and Adventures [...]). (See: Text 22 - Fernão Mendes Pinto)

17 The first fortifications of Macao seemed to have been erected by Tristão Vaz da Veiga.

(See: Text 19 - Gaspar Frutuoso, + Text 23 - Diogo Caldeira Rego)

18 The first Dutch attempts to conquer Macao took place in 1601 when two vessels commanded by J. Van Neck threatened the Portuguese settlement.

19 (See: Text 23 - Diogo Caldeira Rego)

20 "[...] gran chino [...]" [original Span.] (lit.: "[...] mighty Chin [...]") is certainly used by the author in analogy to the expression 'Grão-Mogor' [Port.] ('High Mogul') the traditional address of the Mongol sovereign.

21 It is not unusual for coeval Portuguese chroniclers to critically remark on the contemporary religions and beliefs of the Chinese. Their writings certainly attest that demonstrations of European relativism halt on the border of religious phenomena. In fact, it is difficult to judge the sincerity of the authors' judgements particularly bearing in mind that in those days, before reaching the public at large, all works were first submitted to ecclesiastic approval which was strictly zealous about the orthodoxy of the expressed ideas. Among many other accusations, missionaries repeatedly emphasised the apparently widespread loathsome habit in the Middle Kingdom of the "[...] pecado nefando [...]" (lit.: "[...] nefarious sin [...]") or sodomy. According to modern historiography although homossexual masculine practices were in reality not particularly widespread or encouraged in China, they where nonetheless permissible.

22 "Botente" [original Span.] ("Tibet").

23 The author is refering to the famous Great Wall of China.

24 The author amassed during his Oriental travels a collection of notes on "coisas curiosas" ("curious matters") and, while in Macao, was read books of Chinese history.

25 Previous unconnected sections of the later-called 'Great Wall' of China were first systematically extended and reinforced by the Emperor Huangdi• (r.221-†206BC) of the Qin dynasty in a continuous stretch five-thousand kilometres long, the so-called 'Ten-thousand li• Long Wall'.

26 "estado[s]" (lit.: "[territorial] state[s]"), meaning, 'agrupamentos socials' ('social groupings') - most probably related to the differentiation between the 'people' and 'mandarins' [Chinese government officials]. The author not being knowledgeable of the division of social strata specific of the government of China, makes a curious analogy with the situation in Portugal where [after 1640] the sovereign periodically assembled the Cortes Gerais attended by representatives of the three social strata: people, clergy and aristocracy.

27 "pico[s]" [Port.] ("pico[s]"): an Oriental (Malay and Javanese) and Chinese unit of weight of approximately sixty kilograms.

28 The 'Great Wall' of China is approximately six-thousand kilometres long. {sic}

29 During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) the so-called 'Wall' of China' was constituted by a series of 'sequential' fortifications, which streched from the Gulf of Zhili,• its eastern border, to the pass of Jiayu• or Jiayuguan• [- in the province of Gansu• -] on its western extremity.

30 "chaéns" [Port.] [singular:'chaém'] ("Chaenes" [singular: 'chaem']) = chayuan• [Chin.]: an Imperial censor invested with the functions of Imperial commissioner during his obligatory yearly inspection rounds to a number of the country's provinces.

"tutões" [Port.][singular: 'tutão' ] ("Tuton[es]"). "aitão[s]" [Port.] ("Aaitao[s]")= haidao• [Chin.]: the commander of a Chinese province's coastal defense forces with powers of jurisdiction upon foreigners.

31 The 'Great Wall' is commonly called in Chinese' Wanli Changcheng'• (lit.: 'Myriad mile wall' ).

32 The author's somehow fantasious hidrographic descriptions were most probably derived from Mendes Pinto's Peregrinaçam [...] (The Voyages and Adventures [...]). (See: Text 22 - Fernão Mendes Pinto)

33 Once again the author's narrative seem to borrow from Mendes Pinto's Peregrinaçam [...] (The Voyages and Adventures [...]), the only contemporary Portuguese chronicler who made reference to the "[...] Batampina river [...]" which, according to modern historians, might be the 'Grand Canal', a network of [navigationable, mostly artificial] watercourses crossing vast regions of west-central China.

34 The vocable 'cã' or 'cão' ["Kan" or 'Khan'], used in medieval European literature {sic} to designate the Mongol princes {sic}, became a rooted traditional appelation of the Tartar sovereigns.

35 "coraçon[es] " [original Span.] ("Corazan[es]): the natives of, an province of contemporary Persia. {presently Iran}

36 "champa[s] " [Port.] ("Champa[s]): the natives of Champa, an ancient coastal kingdom situated in eastern Indochina, and partially occupied by present Vietnam.

37 The Chinese army frequently incorporated foreign mercenaries into its ranks, mainly in their positiuons along its vast land border. Other contemporary Portuguese chroniclers such as Friar Gaspar da Cruz and Fernão Mendes Pinto equally allude to this.

This negative criticism which can also be found in other contemporary texts by Portuguese chroniclers seems to contradict the undisputable fact that several kinds of renowed martial arts originate in China. The first Portuguese obviously underestimated the military power of the Middle Kingdom, equivocally insisting on the matter of fact that the Chinese were a weak people.

39 “anchali[s]” [original Span.] or “anchaci[s]” [Port.] ("Anchali[s]") = anchashi• [Chin.]: judge of a Chinese province.

* First edition: Rome, 1649.

start p. 99

end p.