-I- URBAN GAMES

She had received a gift from the gods: a gift hard and shining as a diamond: it was that she lived with the man she loved. Yes, to live with the loved man is a flashing, unquiet gift of the gods. At every moment she realised, astounded, that she lived with the man she loved, and that she exposed herself in all the crudeness and fragility in the daily gestures.

He lived, light as a sunny day, giving life and grace to the hours, moving his admirable body, at once powerful and delicate, among the inert things. From the armpits' shells, she picked up the resinous fragrance of an unheard cedar forest. He lived, dense and alien, an imposing presence filtered by the days without account. He went out with his friends often. Later or sooner, he always came back. In the bath, he would order, with that voice that had the tone of a cello: -"Wash my back!" Intent, she would make the foam slide along the smooth, tense skin. Coolly, she admired that skin almost cold, dry and soft as a new petal. He hummed, enjoying the water. He had the emotion easy and harsh, and he never gave thanks for anything. Kneeling down she would dry his feet with the immaculate towel. The day had its moments of mute adoration.

She belonged to him. He owned her with that passionate rigor with which he enjoyed his belongings: his car, his collection of watches, and his beautiful plastic and iron guns with which, on Saturday afternoons, he played war-games at the abandoned firecracker's factory, near the Taipa road.

He knew himself to be adored; but he never thought of her.

She wove the daily routine, in order not to fall into plenitude. Ecstasy kills. Plenitude corrodes. At the week-ends, alone, she would go for a walk, devising itineraries at random. The round, filled-as-an-egg city helped her to stay anonymous. She walked in the crowd, trying to feel the breath of the many others. To breathe at the rhythm of the passersby is an exalting urban game. Like to guess the desire in the eyes of those who hold hands. Or to spell tenderly the wrong Portuguese of the advertisements, as if written by a loafing, naughty child: LOVO DE PORCELANA E LOUCA DE SENG LONG; CENTRO DE CORAÇAO DESIGN; COBERTORES DE SEDE PURA; LOJA DOS PASSARINHOS QUADRUPEDES; 1a) a sea of consented mistakes, luminous of nonsense and neon. Without knowing why, in this writing with no rules I read a pacifying message: it is allowed to make mistakes. The city will not fall down because of it. BRINQUETOS E BICICRETES; ARTIGOS DE VESTIARIU REUNIAO E CIAL. 2a) She would read it, breathe deeply and happily go away.

One of her favourite routes is to go down the stairs of São Paulo's ruins and, through the narrow back-street alleys, to reach the Junk Hawker's street. Between the stony churchyard and the Mount fortress, the children burst pops and let loose their soap bubbles. It smells of newly cut grass. An old fortune-teller reads one's fate under the acacia. The facade is a mystery, standing up in the air without other walls. High petal of stone. Door of an invisible cathedral built by a wise fire that made into ashes the gilded woodcarvings and the waste of the lath-and-plaster walls. In times past, a multitude of monks and faithful went piously down the polished steps, but long ago the typhoons scattered the last echoes of the whispers of the cults. The old legends of catacombs with a thousand frowns, of hidden sacred treasures, linger deeply, subterranean, under the stairs, and also in old people's tales. Something must be written somewhere. Somewhere in the skin of the city. Indeed, all that moves, vibrates, oscillates, walks, rolls and expands itself over the tense urban skin draws and traces a monumental, imperishable writing.

Squatted in the middle of the street, the woman shuffled through the trifles of the junk hawkers. She would construe dim silver signals: minuscule thimbles, thin enamel hairpins, delicate sticks to scrape the tongue. One day, she found a crucifix; she bought it for six Patacas. Another day, she found two more; the cross of one of them was broken. She bought both. On the following Saturday she came back; there were more of them; she bought them. She passed the afternoon of Sunday washing them, brushing them, polishing them with metal cleaner. She wrapped all of them in a square piece of silk. Lost in her thoughts, she looked for a box where she could put those and maybe others.

I stash the crucifixes one by one in a lacquered tiger's eye coloured box. Without a shadow of a doubt, these are crucifixes that come from rosaries or chaplets, for a frail chaplet could not uphold the black wood of this log, and the figure of Christ must be made of lead; in the knees and in the soft chest, and in the place of the absent thorns, filed and polished no one knows by which devoted hands, one can see the blaze of the lead under the worn-out copper-coloured plated metal.

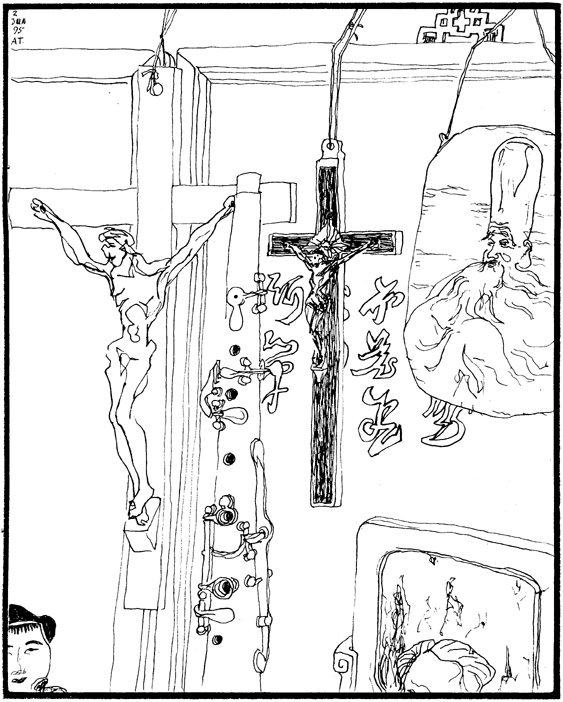

Sem título(untitled).

ADALBERTO TENREIRO

1995. Ball pen on paper.19.1cm×24.1 cm

Sem título(untitled).

ADALBERTO TENREIRO

1995. Ball pen on paper.19.1cm×24.1 cm

I already have eighteen Christs, some bigger and some smaller, even a minuscule one, made of carved, rosy silver, that must have a copper league; yet it was not oxidised when I picked it from among the pinchbecks inside a cracked bowl, lying in the floor of the Junk Hawker's Street. I removed the dust veil with the tip of my finger, it already shone, and it keeps shining until today, delicate as a little piece of lace. Maybe it came from a girl's chaplet, maybe, who knows. One of the most beautiful and mysterious items seems made of bronze; the cross has inlaid wood, held by the big nails that flatten and pierce the hands of the Lord. Behind the head it has a triangular brightness; still visible are the almost vanished beams of the light that emanated from the divine face - what a face! What remains from it is a delicate, feminine oval looking without eyes to his right hand. The polished neck seems to eternalise a most deep inspiration, what will happen when the Lord will rest and deflate the chest in the deepest sigh that anybody ever heaved. The fine waist moves a jot, taking to the right - oh, mystery - an opulent, motherlike hip. I know that the illusion is due to the fact that the prayers touched, caressed, rubbed until wearing-out the narrow pleats of the sash that protected the human nudity of the divine saviour represented here. But the image troubles me and this feminine Christ irresistibly reminds me that God is Father and Mother, and that Christ and the Mother Church are no more than One, amen.

From where do thus these fallen crosses come from? From São Lázaro or Santo Agostinho? From the Cemetery of São Miguel or from the works in the Ruins? I do not know; I only know that I buy them in the street, I rifle through the junk scattered in the plastic spread in the ground: old coins, brooches without pins, watches without bracelets, unmatched earrings, amulets, chromes, almanacs of years past. And sometimes crucifixes.- "Gei-do chin-a?" - "Sap man." - "Sap man? Hou gwai. Peng-di, dac, m'dac?" - "Dac-la! Leung go, sap-I man."3a) These two seem to have been shaped by the same hands except that in one, the brightness is round, and it does not have the ribbon showing INRI. Some have the extremities of the cross shaped as a lily; the encyclopaedia states that it is the cross of St. James. This one, stretched as an icon on a flat cross, is only three centimeters long, has his fingers separated in groups of two and the slender muscles of his arms and shoulders perfectly shaped. One can count the ribs, and the tense abdominal muscles in the concave arch of the abdomen show an intense pain. The crimped knees, the closed eyelids, the line of the nose, the curve of the lip, infinitely sad, were carved with such rigor and precision that one always sees the same touching expression, regardless of the perspective from where one looks. Above and below the line of the arms, it reads: STAT CRUX DUM VOLVITUR ORBIS.

In none of them could I see made somewhere. None of them shows a punch from a workshop or a mark from a craftsman. In any European city, they would be no more than old pious objects. In this one, called of the Name of God, they proclaim the magic fascination of martyrdom, and the astounding mystery of the holy nakedness.

- "Ana!" he called from the threshold of the room. Only a silence answered him, one that he took for a minor betrayal, an unfair sulkiness. The voices of players, down there at the Tap Seac field, and the chirping of children in the playground of neighbouring schools, came to him, filtered by the distance.

- "Ana Luisa!" he called again, lacking conviction now. He straightened himself when he met his own look in the mirror. Lost in his thoughts, he undressed and put on his bathing robe. Smiling, he swore a harmless curse in Cantonese; but immediately after he crimped his mouth for a strong Portuguese swear. He put away his bathing robe and entered the shower. He cursed again: the one who would pass him the clean towel was not there. Where could she be gone? - he wondered, astonished. He dried himself with the towel that he had used in the morning. Without knowing why, he felt slightly guilty. Lately, he had slightly neglected testing the effectiveness of his power, of the soft power of seduction. He looked at his immaculate nakedness in the mirror. Like a pebble, like a crystal. The innocent nakedness in the intimacy of the empty room. The useless nakedness, without the mute admiration of the woman's eyes. He found himself puerile, and got dressed quickly.

-"She felt like wandering around!" he said aloud, intimately attentive to the fact that this was only part of the truth. Suddenly intrigued, he looked round the room with enquiring eyes. He opened two drawers, touched the impeccable order of the white clothes. He opened a cabinet and smiled to the perfect lines of his toy guns. Suddenly, with an involuntary hand, he took from the top of the cabinet the lacquered yellow box. He stopped, suspended in the act of opening it. He felt its weight and found himself wondering; if they were watches, the beat of the hidden mechanisms would already be heard. He walked to the penumbra of the corridor, holding the box on his hand.

Piled on top of each other, polished and solemn, at the bottom of the box lined with a piece of silk, and without any understandable order, were the old crucifixes.

- "Jesus!" he swore again, now in English. - "Where this come from? Is it possible that she became sanctimonious without me noticing it?"

He went to the balcony, he looked, without seeing them, at the houses and at the quiet boats in the dimmed copper water. The day was falling behind the mountains of China. Vaguely troubled, he lighted a cigarette. He wondered whether he should go out for dinner or wait until she came back... or simply not eat.

His perplexity lasted the time of a cigarette. Although his friends expected him to show up only in two hours time, he took his pager, his wallet, his car's keys and radio, and he went out into the night.

-II- THE WOMAN ON THE VERANDAH OVERLOOKING THE RIVER

In bed, when she closed her eyes, she saw the darkness of her eyelids studded with moving stars. She did not know where those trembling stars came from, from the boredom of a long and mute loneliness, or from the tense and strangled words of the quiet silence of the passing days. For how long had she not written or spoken? She stretched her body between the fresh, soft sheets, brought from old Europe, knitted by hand long ago. Despite the loneliness, she felt her body slim and alive, within her own heat.

She fell into the easy sleep of those who have the flowing of time as an ally. She woke up in the middle of the night, rose numbly, suddenly attacked by a dense, viscous and noxious odour. She walked to the bathroom, to see if the unusual smell came from there, from the depths of the vertical pipes of three floors, with four flats per floor.

After all, the gauge of the VCR black box was at four in the morning. Already a pale silk rectangle emerged from the river, climbed up to the verandah, glued to the large window, drawing like a painting the tall bamboo leaves, the camellia and the dwarf jasmines.

The putrid smell did not come from the bathroom. She stopped in the middle of the room, her nightdress wrinkled, her hair rumpled, flakes of sleep leaving her defenceless and stupid. She was reminded of antique engravings, far away, in childhood, belonging to an old aunt who lived in seclusion at Santa Clara. She was reminded of precocious readings from pious old books, found among the dust and shadows of the attic. It was written. Succubus and incubus invaded, sometimes during inauspicious nights, the rooms of lonely sleepy women. Pestilent smells of uncertain origin always announced hidden demons.

She shook her hair and opened the window wide, suddenly laughing at the dead beliefs that memory hides, even if we do not believe them. It was just that. A dirty, insidious and mean wind, made overlasting rubbish dance on the street corners. In the cages of a thousand verandahs, birds sang, muted. Although it was the late May, one could not see even a tiny bud in the branches of the red acacias. Another day was beginning, warm and slow.

She decided to go back to bed. Until seven o'clock she would still have almost three hours sleep. She saw herself sideways in the mirror of her bedroom. A magic mirror bought for a hundred patacas at the tin-tins, at the beginning of the Year of the Rabbit. There she was that unknown woman, framed in an innocent garland of carved peonies. In the bathroom mirror she saw herself as she was: dull skin and premature wrinkles. Eyes sunken from looking inside herself, by ritualised tedium. However, in the mirror of peonies her eyes were shining like sands from other places, and everything in that picture brought back the memory of beaches, dunes, the two blue infinites of water and sky, sometimes cut by limpid, drastic wings.

Everything strident like trumpets bugles, by force of that divine impetuosity which changed into beauty there on the borders of the Mediterranean world. Where I was born, she thought with nostalgia, returning to the window. She look extensively at the mountains of China, on the other side of the Pearl River. The geometry of shadowy roofs still appeasing. The fragile green, green lacework of the trees in a few backyards, everything torn away by the vertical mass, oppressed by very new buildings, always growing, like a hope which changed into condemnation. She painfully loved this involuntary town, made of layers of different people. Born on the fringe of two antagonist civilisations? Bacco and Confucius? Christ and Lao Zi? Damn antropohistory, thought the agonized woman. Around her the bamboo skyscrapers were growing and thousands of caged birds woke up, calling out, warbling or chirping, shaking their nice cages, still covered by nocturnal white covers.

Macao does not waken up because Macao never sleeps. She too, slept less lately, wanting eagerly for dawn. She would then go to work, already smiling and smelling of expensive soap, on the outside keeping the serene rituals of the day, and inside with the strained heart of those who live awakening to the secret rhythm of a hidden clepsidra.

In the afternoon she would go to the Academy, newly buily in an old, restored building. The skill of the architect, versed in fengshui, and the firecrackers on the opening day could not exorcise the ghost of the family. A long time ago there lived there a woman who died of betrayed love, dressed in red so that she could make sure of many, many centuries of haunting. Neither the hexagonal mirror, nor the aquarium with goldfish at the entrance, on the advise of the bonzo, could sustain the discreet flow of strange things: ragged pieces of songs from the time of Cixi, losses, voices, misunderstandings and the gradual madness of the women living in the House.

But the woman aon the verandah at dawn, feared none of this. Since childhood she had been used to the atmosphere of old houses, with their tales and ghosts. She went there regularly to engrave the controlled fever of the days on the copper. Walking to and fro among the resin box and acid chamber, wet paper and the hieratic English press. The other engravers were attentive and silent. And the permanent teacher, mellifluous and confucian, more confucian than Confucius. Making with his own hands, for the submissive beginner students, the carvings for the competition - a fierce fight for prestige with the Hong Kong teachers. Confucius said: friendliness is more precious than integrity. That he himself, chosen by the heavens will not deny the use ofobscure means to make sure that the Workshop would never fall into the hands of his enemies. And she, like a sister, would support him in everything with loyal devotion, and abandon those stupid, moral scruples, not well fitted into this part of the world. Had she lost trust in him? Had not his mother given him the name of Valuable Omen.

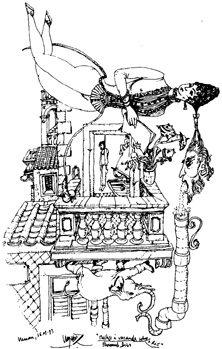

Mulher á varanda sobre o rio (The Woman on the Verandah overlooking the River).

CARLOS MARREIROS

1995. Ink drawing on paper.

And the woman will return to sit again with them, drink tea and eat rice. And Guangdong Duck, and Wa-wa Fish. And her hair will fall straight and long down her back, and her skin will look like the colour of old ivory. And, grateful, she will learn what is learned when in love, with frenzied but lucid love; not enchanted but obstinate; not a person, nor a city, but the proper circumstance of just being, breathing, like a tiny animal in the middle of a crowd. In which, slowly and inexorably, the name and person are diluted and lost.

Morning grows, without splendour or freshness. The woman is still wandering on the verandah. Ah! But tomorrow it will rain heavily and the merciful rain will wash the dark dust, throw away the rubbish, return the radiance and solemn glory to the pagoda trees. She will then go to Lou Lim Iok garden, and will sit in the Red Pavilion, seeing the willow trees almost touching the lake. Then, like in those novels of the colonial era, a man will come with a book, obsidian eyes and the hands of a calligrapher. He will sit next to her, with his thin fingers showing the characters, and in a beautiful, antique Portuguese tone will say that in the year one-hundred before Christ, Su Wu composed this poem. He was going to war against the Huns, on the edge of the Gobi desert, and the words he wrote are still alive as though he were them today. With his finger on the brown pages, and with half a smile which is all that is permitted, he will painfully translate the poem, apologizing for his immense inaccuracy in his arduous search for words nearer to the feeling, as it can never be near to the music. And he will read:

"In our wedlock we are man and wife,

Our love is never broken by doubt.

Let us enjoy once more such life,

Because tomorrow I'll set out.

Thinking of the long way, I'll go,

I rise and see how old is night.

Dim in the sky all the stars grow;

I'll part from you before dayligh

Away to battlefield I'll hie,

I know not when we'll meet again.

Holding your hand, I give a sigh;

Letting it go, mey teardrops rain.

Try to love spring's delightful view;

Do not forget our happy days!

Safe and sound, I'll come back to you;

E'en dead, my sopuld with you e'er stays."1b)

No, the woman is not seated on the bench of the Red Pavilion and no literate young man is reading poems of the Han Dynasty. It is just that the morning is beginning, entangled in dirty wind, and this woman has a delirious imagination. What does it matter, possessions, thousands of hawkers enter through the Portas do Cerco [Border Gates] with their fish, pigs, vegetables, salted goods and countless fresh, moist, rosebuds.

Yes, the appeasement comes when we realise we are alive, transplanted but alive, and that this feeling of having left the feet on the other side of the world is the mother of all exaltation and melancholia.

The woman, already awake, leaves the verandah overlooking the river and goes to work. She is innocent, un-named, among the crowd of little children and parents on their way to school, of old men with cages going to the gardens, of taiji learners, of florists sweetly saying mai-fa mai-fa, 2b) of car-washers with vertical featherdusters like Don Quixote.

Ah! Everything is right as always she said to the indifferent beggar who writes eternal characters in ochre on the pavements.

-III- POISON

It is half past seven. The night has fallen completely. The sky wears a deep black; although yesterday, when I arrived, all the stars shone, huge and cold like gemstones.

The wind makes the coconut trees moan and the palm-leafed roofs crackle; and the continuous wailing of the sea, the shrieks of the domestic imprisoned monkeys, the heartrending, periodic appeal of an unknown bird, the choir of crickets, cicadas, frogs and toads make my sleep, which arrives late, restless and brief.

Yesterday I dreamt of you, dreams of rupture and farewell, I repeatedly awoke without knowing where I was, the reality stranger than the dream; icons on the wood walls, our Lady of Perpetual Help, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, a huge rosary. The mosquitonet, falling from the ceiling as a tent of purple gauze, lends to the objects a screened, rose colour.

This morning I dedicate some time to observing the objects on the table: one kerosene lamp with a pink glass; a novel by Agatha Christie, Vallon, and the book of the national hero, Noli Me Tangere, with its used, dirty cover; a magazine of architecture, a pack of cards with pornographic figures, a blue rosary inside a transparent plastic box. Objects without a reverse, avaars of a reality without symbols. Some belong to the owners of the house, others lay were abndoned by the holiday-makers. Everything so intriguing and almost hostile. Over the plastic a pattern of big bluish-green fruits, with a yellow halo in a distorted impression. If you were here, they would torment me as goads, because I would try in vain to see them as you would.

For one night I live here and wake up at six in the morning with the strident singing of the roosters, the cries of children, vigorous sweeps in the earth paths, the barking of dogs, the chattering of the parrots inside their cages in the small restaurant at the top of the narrow pebbled staircase. I wake up and I feel like for ever before and after, this was my room, under the palmleafed roof of a house-on-stilts, on the craggy slope above the sea, in the middle of the coconut tree's plantation. And like this strangeness that makes me look at everything around, and the precious embroidery made by all of them together, was due not to the fact that I arrived only yesterday, but to a chronic sight disorder.

Blue sea, I say to myself. Holidays, blue sea, white sand, corals and shells, coconut trees. Green mountains in the mist, slim boats cutting through the water, old songs of the Pacific. But with my eyes of frosted glass, all I see is dull. I know that you are waiting for me and that you practise in front of the mirror the words with which you will summon me; I will be the only one to hear the echoes of the tumultuous farewell, in the courtyard of the Peak Garden. Solitude is a minor affliction. If you were here, everything would be transformed. I do not even know how I would see what I see so simply now.

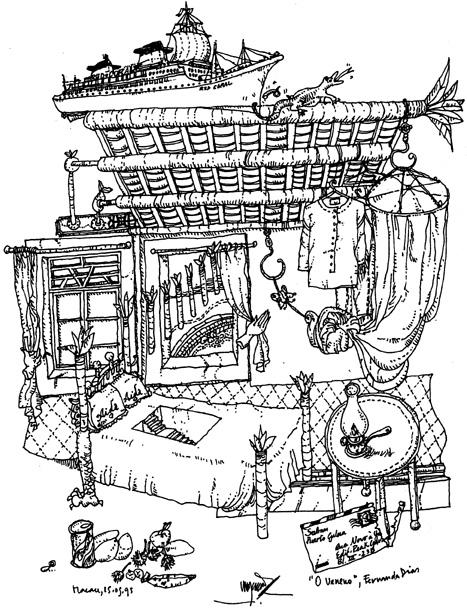

O Veneno(Poison).

CARLOS MARREIROS

1995. Ink drawing on paper.

I enter the room next to mine, thinking that it is not occupied. I am surprised by the strict cleanliness and by an unnamed perfume, almost imperceptible. Between the two windows with muslin curtains, a wardrobe made of embossed wood with its two mirrors, one long and narrow, the other round, at eye-level, surrounded by naїve roses. On the table without a plastic cover, the eternal kerosene lamp. The white mosquito-net tied in a big knot above the bed. Over the white bedcover, two cushions embroidered with stitches forming small buds, making a new wine coloured name on the raw cotton: Aida. In a rope tied to the two wood beams in the corner where the roof bends, some hangers with clothes. I look at them without touching them, as if in a museum. A long, faded pair of jeans. A white blouse with no more fripperies than a row of buttons and some slim pleats. An earth-coloured sweater. A grosgrain ochre dress, without pockets or buttons, falling straight. Everything so strict and clearly functional, I think without believing it. But thus it is. Whoever lives here, or whoever was temporarily here, most evidently likes clear and austere things. And the form and size of these clothes show clearly that a slender and agile body inhabited them.

In the heat of ripe fruits, in a paradise full of mosquitoes and twittering sounds, someone lives in an intolerable perfection. I look at everything around, I look intently again, I look for an ugly spot in that clarity, I do not know exactly what. A comb with hair? A pinchbeck necklace? Any mean, feminine small thing, which would triumphantly break that harmony. But I do not see anything except strict indispensable things, in a halo of rigorous hygiene, from an unaffected, uninteresting life.

Then, suddenly, like someone who wears a lead jacket, I become conscious of my body, while I imagine that girl, who can not be anything but beautiful. Light and healthy skin, tea colour eyes, cello colour hair. The gestures, slow; the smile, rare and serene. And a mysterious and restrained life for ever far from the scope of the delirium of my imagination.

A deaf anger and a visceral fright trouble my sight. I kneel down on the patchwork carpet. Like in a dream, I listen to your voice, husky by the desire for another one. The music of terror sounds foolishly in my ears, dragging tatters of past humiliation. I know, with an old wisdom of many years, that I am going to suffer without remission. Real pains and others - imagined with a cruel refinement. With a bitter taste in my mouth, I open the drawer, which creaks with the innocence of old tales. I see only white underwear, without laces or ribbons. I close the drawer, astounded because I dared to spy on that intimacy. As I stand up, the room slides under my feet, turns around me, the plan of the cartoon is changing, everything newly drawn by Marreiros, outside the coconut tree plantation, the blue sea, a boat called Red Coral in the sand.

I come back slowly to my room, I take the already addressed envelope, Rua Nova б Guia, "Peak Garden Building", Block III, 2 B, Macao, I tear to pieces three sheets filled with a scattered, almost illegible handwriting, I tear to pieces the envelope also, sender: Sabang, Puerto Galera. I know that you will come, if you receive this letter. I imagine you at sunset, sitting on the narrow verandah, drinking Coca Cola, listening to your music. The peaceful fat geckoes chasing mosquitoes around the lantern. The mangoes and the jack-fruits in the fruit-dish, exhaling the strong nocturnal smell. A bunch of girls springing like little birds over the Red Coral. Then that indefinable girl will pass like a breeze, on the way to the beach. The girl that I never saw. She will pass, polished and shining like a sea shell. With no words and no past. The velvety night of the Pacific, opening in the dark, sweet as traps corollas. And me dying again the ignominious death of jealousy. More than being betrayed, it is the invention of betrayal that hurts. I tear the letter to pieces with a slow determination. Ferociously, I consider the solitude of the white nights to be. For I will not tell you to come. For what intrigues me will attract you. A deaf, malign drum, would sound in the palm plantation. Standing, behind you, with my hand on your shoulder and my breath in your hair, inside me the bleary love would slowly turn into poison.

All Three Short Stories translated from the Portuguese by: Ana Pinto de Almeida

1a)Most probably a consequence of the lack of knowledge of Portuguese language by the Chinese, the nonsense of these phrases results from orthographic misspelling of Portuguese, thus giving rise to a number of ludicrous interpretations.

LOVO DE PORCELANA E LOUCA DE SENG LONG (Port.: Louзa de porcelana e louзa de Seng Long; trans.: Porcelain Wares and Seng Song Wares). "LOVO" has no meaning in Portuguese but most probably is an orthographic misspelling of 'Louзa'. "LOUCA" as written (i. e.: 'louca') means in Portuguese 'a mad woman', the second half of the sentence thus literally meaning 'a mad woman from Seng Song'.

CENTRO DE CORAÇAO DESIGN (Port.: Centro de decoraзгo e design; trans.: Decoration and Design Centre). "DE CORAЗAO" as written in two separate words (i. e.: de coraзгo) literally means in Portuguese 'of heart'. Amongst several possible, a more immediate interpretation could be 'the centre of a heart called Design'.

COBERTORES DE SEDE PURA (Port.: Cobertores de seda pura; trans.: Pure Silk Quilts). "SEDE" as written (i. e.: 'sede') means in Portuguese 'thirst', the sentence thus literally meaning 'Pure Thirst Quilts'.

LOJA DOS PASSARINHOS QUADRUPEDES (Port.: Loja dos passarinhos quadrъedes; literaly trans.: The Shop of Little Birds with Four Feet). Self explanatory.

2a)BRINQUETOS E BICICRETES (Port.: Brinquedos e bicicletes; trans.: Toys and Bicycles). The change of a "d" for a "t" in the first word and an "1" for an "r" in the second word possibly derives from the difficulty the Chinese have in orally pronouncing some Portuguese consonants, swapping them for others, as is the case with the "t" for a"d" and "r" for an "l". In this case, possibly due to an excess of zeal in correcting the oral pronounciation of these two words (i. e.: "brinqueTos" and "bicicRetes"), the process has been reversed, resulting in the orthographic misspelling of the word.

ARTIGOS DE VESTIARIU REUNIAO E CIAL (Port.: Artigos de Vestuбrio "'Reuniгo" C[ompanhia] l[nternacional] A[nуnima] L[imitada]; literally trans.: Clothing Items "Reunion" and C[ompany] I[nternational] A[nonymous] L[imited]). Self explanatory.

3a)-"Gei-do chin-a?" -多少钱? (-"How much does it cost.?")

- "Sap man." -朗奕(- "Ten Patacas.")

- "Sap man?" - 朗孩(- "Ten Patacas?")

- Hou gwai. Peng-di dac, m'dac. -很贵. 便宜,好不好? (-"It's too expensive. Can you make it any cheaper?")

- "Dac-la! Leung go, sap-I man." 好啦, 两个十二元. (-"Oh well! Two for twelve Patacas then.")

1b)SU Wu苏武 To my Wife, in: XU Yuan Zhong trans. - vers.,"Song of the Immortals: An Anthology of Classical Chinese Poetry", Beijing, New World Press, 1994, pp.21-22.

别妻

结发为夫妻, 恩爱两不疑。

欢娱在今夕, 燕婉及良时。

征夫怀往路, 起视夜何其。

参辰皆已没, 去去从此辞。

行役在战场, 相见未有期。

握手一长叹, 泪为生别滋。

努力爱春华, 莫忘欢乐时。

生当复来归, 死当长相思。

2b)Mai-fa mai-fa 买花 买花(mai hua maihua) (buy flowers buy flowers).

*Author of Horas de Papel (Paper Hours), published in the "Poesia em Papel de Arroz" ("Ricepaper Poetry") Collection of Livros do Oriente. Top Award winner of the competition Prзemios Macau de Conto 1992 (Macau Fiction Awards 1992), with the short stories Dias do Beco de Prosperidade (Days of the Prosperity Alleyway) e Rompimento (Rupture) published in the magazine "MacaU", in October and December 1992, and "Devaneio em Hac-Sб (Hac-Sб Reverie)", published in the periodical "Face", in July 1993.

start p. 157

end p.