PREVIOUS PAGE:

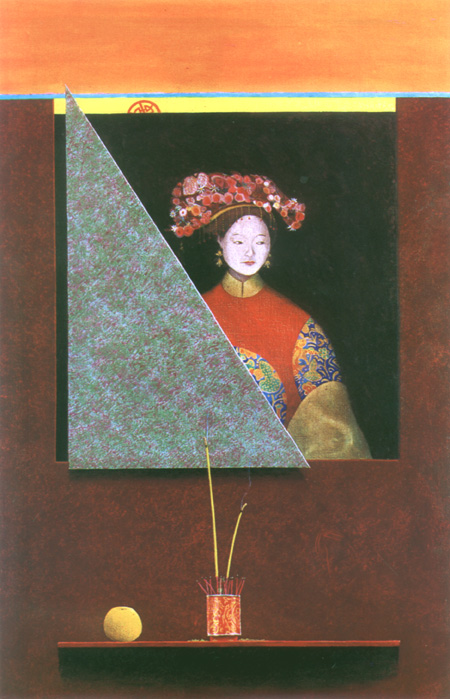

A Noiva Manchu (The Manchu Bride) - detail.

NUNO BARRETO.

1995. Oil on canvas. 118.0 cm x 164.0 cm.

Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation Collection), Lisbon

PREVIOUS PAGE:

A Noiva Manchu (The Manchu Bride) - detail.

NUNO BARRETO.

1995. Oil on canvas. 118.0 cm x 164.0 cm.

Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation Collection), Lisbon

"When from my sorrow

The lengthy imagination my eyes soothe

In my dreams that soul emerges

For me it was a dream in this life.

There is such a longing

Where the sight stretches and languishes

I run after her; and she seems

To part even more from me

I shout: - Don't run way, gentle shadow!

She, the eyes set on me, in tender fear

As saying that it can be no more.

Once more she runs away; I shout again: -Dina...

And before she says a word, I awake up and see

That not even a short delusion I can have."1

Luís de Camões

It was a day of military departure, in Macao, in the 1960s. In the wooden pontoon of the Outer Harbour stretched a shadow of khaki uniforms. The tarred hull of the barge swayed with the tide, and the coolies started to untie the knots of the thick ropes for the departure. Faraway, where the bottom of the river was deeper, wrapped in the mist of every day, stood the boat that would take to Mozambique and Portugal the returning military, whose duty had been served. Haste and confusion; sacks, bags, last minute parcels. The red headpieces of the African soldiers had already departed. The shouts of the coolies synchronized the barge departure manoeuvre, crossed with the orders from the officers. Suddenly, among that disorderly noise made of whispers, laughter, strong hugs, to which was added the monotonous sound of the brownish waves combing the pier, sounded an anguished cry:

- "Mammie!"

Over the ochre shoulder with golden stripes of a sergeant, who was almost running to the barge about to depart, came into view the blond head and the small raised arm of a child who struggled and constantly repeated:

- "Mammie!"

The sound faded like the vision attenuated amidst the mass of uniforms shouldering together in the boat that was shoving off.

On the ground lay torn papers, remains already without name, maybe crumpled remains of longing.

The badly jointed old planks of the pontoon, now revealed the brown water of the river where more remains floated. It was what was left behind by the ones leaving: remains.

Standing close to me was a young woman. She was a Eurasian with traits predominantly Western, pretty, wearing a red minape2 in which were lost the tears running down her face, a face that smiled until a while ago, when courageously she waved to the little departing daughter.

-"Mammie!"

Even today I can hear the echo of that cry.

It was then, that for the first time I paid attention to the Macanese woman, Eurasian and 'illusive', sometimes so disrespected because of being so badly understood by the passing men arriving from the West.

If there are various documents where it is possible to collect social anthropologic information relative to the Portuguese women of the East, relative to Macao, these are scarce and often ambiguous. The writers who wrote about them spoke only of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, of slaves that had to be expelled from the Colony, "of men who lived in sin", of orphans who needed to be protected and married-off.

In accounting for the actual numbers of these women, they are globally referred to, contrary to the men who are registered as sons and grandsons of Portuguese, nhons3 and natives of the Colony. The women were only described relative to their civil status: married women or maidens, or as res nulla.

Two Chinese Mandarins sent to Macao to investigate the situation of the City and its residents considered two groups of Portuguese women "[...] in accordance with the colour of their skin [...]": whites (the mistresses) and blacks (the slaves and/ or maids). These accounts date from the eighteenth century4 when most of the slave women were from Timor, the blacks being more rare due to the difference in the prices of the respective purchases. Then, the City was impoverished and lived from the trading voyages to Timor and to some ports of India and Cochin-China, far way from the years of wealth that had faded by the end of the seventeenth century,

Curiously, it is in the accounts of the travelers, mainly foreign travelers, where we find references to the women of Macao, though such accounts are rarely exempt from a strong ethnocentrism.

Which women would have accompanied the first Portuguese men to Macao? What would have been the fate of their daughters and what place would they have occupied in Macanese society?

Resorting to the letters of the Ecclesiastics and the annals of the Jesuit missionaries5 who opened from Macao the door to China, and as well as the accounts of the travelers passing through Macao between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, we can have some knowledge about these anonymous women, to whom the Portuguese owed so much when they settled in Macao.

In the beginning, the Portuguese adventurous life in the China seas, documented by various coeval reports such as the letters written from Guangzhou by Cristovão Vieira and Vasco Calvo6 and even the Peregrinação by Femão Mendes Pinto, 7 make us believe that they were only accompanied by slaves or occasional frivolous women to whom Fernão Mendes Pinto refers in the description of a shipwreck. However, according to that same source, in Liampó [Liangbo], the Settlement that preceded the one of Macao, "[...] there were [...] three-hundred men married with Portuguese and mestizo women".

Who were these Portuguese women to whom Fernão Mendes Pinto refers, as Portugal forbade the embarkation of European women to the East except in very special cases?

We do not believe that Portuguese women from the Kingdom, either went to Goa or were born there, nor were they taken to China by men who made from life a true adventure. Besides, when the said orphans of the King started to be sent to Goa, by Royal Decree their marriages should be contracted only with chosen men and "not with soldiers of fortune". In what concerns the girls born in Goa, daughters of those European mothers, they would be the ones with good dowries and therefore their marriages would also never be with those kind of men. The same would be considered in what concerned the legitimate daughters of the Portuguese and the natives of the territory.

Besides, there were many Macanese girls who took their vows in Goa, in Saint Monica's Convent, maybe precisely because their parents or tutors did not find for them desirable husbands.

In accordance with historical sources, in the first years of the settlement of the Portuguese in Macao, the majority of men had only a temporary residence there.

However, in 1563, Fr. Francisco de Sousa, when describing a procession in the Settlement of Macao, says that"[..] the girls were at the windows with garlands in their hair and silver plates full of roses and vials of roseate water which they threw over the canopy and the passing people".8 A similar thing took place in Goa and possibly in other settlements in the East. The same writer also says that, on that same date,"[...] some orphans and many Christians of the Colony who for a long time had lived in sin were married. More than four-hundred-and-fifty expensive women slaves were shipped to India and in the last vessel that sailed to Malacca there were two-hundred who were the most dangerous and most difficult to throw away."

From this report it seems that it can be confirmed that the women who accompanied the first Portuguese men to China were slaves bought in the Eastern markets, slaves that also followed them in their boats, in the Eastern traditional commercial trading manner. The orphans to which Fr. Francisco de Sousa refers would possibly be the daughters of the Portuguese, the Eurasians who lived in the concubinage system.

The missionaries, moralizing mission was difficult and so many were the abuses that in the Diocese of Goa Constitution, published in 1568, the marriages of the Portuguese were regulated in the praças do Oriente (Eastern Settlements), especially the men who were already married in the Kingdom and did not intend, or could not return there, to avoid the crime of bigamy. 9

In the small trading voyages, the women accompanying the Portuguese in their boats - and, not rarely, sold in different ports - continued to be constant, and soon they were also taking Chinese women who had been bought, from Macao to Goa, and possibly their half-cast daughters, besides thejapoas (Japanese) the cheapest slaves by the end of the sixteenth century.

The abuses shocked the Catholic Church and the complaints soon began.

So, in 1607 Portuguese men were prohibited to take along women in the ships, unless they were traveling with some mistress authorized to board the vessel. This prohibition was proclaimed in all Asian market places including Macao, but the truth is that the trade of slaves from Japan, muitsai (Chinese)10 and after, timoras (from Timor) and probably women of other ethnic groups continued for quite a long time, even until the abolition of slavery by the end of the nineteenth century.

Besides, such facts can be confirmed by the reading of various regulations either from the Kingdom, the diocese, or from the Chinese authorities, in order to curb such trade. According to Fr. Gabriel de Matos, one of the things that shocked the Mandarins was to see the Portuguese "[...] captivate Chinese women, buying or selling them abroad [...]. Sometimes [...] boats loaded with boys and girls sailed to other kingdoms." In the seventeenth century, the Fr. Caetano Lopes also protested in writing against this type of slavery. 11

In 1617, the aitao12 of Guangdong published a Decree by the Wanli Emperor (r.1573-†1620) in ' which the Portuguese were prohibited from "[...] buying any subject in the Chinese Empire." However, through bribing the Mandarin and trafficking with less scrupulous Chinese it seems that this decree was not always obeyed.

In addition, already in the sixteenth century the Kingdom had intervened in the repression of the trade of slaves in the East. This was because, from the markets in the Arabian countries to the famous markets of Goa, the Portuguese could buy women slaves native from many parts of Africa and Asia, incrementing this trade in such a way that, after 1520, the Portuguese King Dom Manuel I prohibited "[...] bringing to Europe slaves of any caste [...]"; a prohibition reiterated in 1571 by the King Dom Sebastião.

In 1595, because of the sequence of complaints from the Chinese authorities against the Portuguese who bought girls of that kind to be their maids and exported them as slaves, sanctions where established such as: fines of one-thousand cruzados13 and two years of fixed residence in Daman, in the Portuguese State of India.

However, the trade of the muitsai continued, with many men concealing their crimes under the cover of a charitable intention: conversion to Christianity, through baptism. The truth is that feminine infanticide was a current practice in China, and then many Chinese through misery, instead of killing their daughters, sold them to the Portuguese. Others stole them or bought them from their fellow countrymen to resell them in Macao. This trade of stolen or resold children seems to have been the way most used to buy muitsai, because many Chinese, maybe the majority, were afraid of their deceased ancestors revenge in case of their progenies change of religion, adopting the one of the "barbarians," if the children were sold directly to them. However, there were many Chinese who had no scruples whatsoever about trading chidren in Macao and thus huge profits were made in these dealings.

In 1624, the Portuguese Kingdom legislated again, prohibiting the purchase of Chinese children. However, that Law again continued to be ignored in Macao. The men who lived there, almost all still rich and powerful, paid little attention to the rules of the Kingdom, used as they were to be practically self-governed, far way from the jurisdiction of Goa, and having as leader of their Senate a group of people who were not always detainers of the virtues required from a 'homem bom' ('good man'). 14

Josef Wicki15 says that in the sixteenth century it was common to hear stories about men living in Malacca (from where Saint Francis Xavier had departed without making many conversions in its inhabitants), that, being married "[..] who had three or four concubines and, many, half a dozen".

The situation was the same in all the Eastern Settlements, in what concerned the family institution of the Portuguese majority. In 1715, the 'Pai dos Cristãos' ('Pastoral Priest', or lit.: Father of the Christians - the Bishop of Macao) prohibited once more the purchase of women slaves and the sending of muitsai from Macao to Goa, or any other place.

Along with Ecclesiastic censures and pressure from Chinese authorities16there also continued the prohibitions from the Kingdom, in reality without much practical effect.

In the eighteenth century, with the decadent commerce and increased hardships, Timor became one of the new sources of slave supply, which led in 1747 to a new prohibition by the Bishop of Macao, relative to the transportation of "[...] Timor women and other women [...]" to the City of Macao. The Senate pronounced against this Ecclesiastic prohibition, as their members felt hardship in their businesses and domestic economy.

It was finally in 1758 that the Marquis of Pombal [Prime Minister of Portugal] gave the deepest blow against the slavery of Chinese girls, proclaiming that within twenty hours freedom should be given to all those who were still captive.

However, this situation was only later definitively solved, by the Law of the 23rd of February 1869, which led to the extinction of slavery in all Portuguese domains.

To escape the multiple prohibitions implying punishment to whoever enslaved Chinese girls, the prohibited condition of slavery led to the creation of a new category in the family structure of the Portuguese of Macao -the criações. 17 This category was maintained through the whole of the nineteenth century and continued in the first decades of the twentieth century. The criações were already mentioned in the wills of the Portuguese of Macao, at least in the beginning of the eighteenth century, as can be verified in the documents existing in Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Misericordy) of Macao. 18

In the 1960s we still knew Macanese ladies in Macao who had been criações19 of wealthy local families. They were not slaves but they were also not totally free.

Also at that time, there was also still talk of nhons, nhins, 20 and nhonhonha, 21amas, 22aias and bichas, 23 reflecting varying social positions of Macanese women, Eurasian and Chinese and even of other ethnic groups integrated into the local families.

The criações were the children bought or the illegitimate daughters and sons of the head of the family or his progeny nhons. They had a status that was not quite like the bicha, or old slave or servant, but was also not afilhada24 as we understand this phenomena in metropolitan Portugal and which still exists in many of the country's villages.

The slave women and their daughters (who were also slaves or could be freed by the most generous masters) were for a long time quite numerous in Macao. This caused a great imbalance in the sex-ratio and led to foreign travelers registering in their narratives comments of an uncomplimentary nature in relation to Macanese women.

The slaves were bought, inherited, sold or offered at their masters will. The last timoras25 and their freed progeny lived in the beginning of this century, in the precincts most probably depreciatively known as Baixo Monte (lit.: Low Hill), side by side with Chinese, mostly refugees.

In the seventeenth century, Peter Mundy26 described Macao as being still in its golden age and referred to the Macanese women and to the kimonos the children of the wealthiest families wore at home, noting the "[..] precious jewels and the expensive trimmings. [And he added...] In this place, there are many rich men, who dress in the manner of Portugal. Their wives, like the ones of Goa, dress in fine cotton fabrics and condês, these over the head and the others from the middle of the body down to the feet, and they put on flat slippers. 27 This is the common dress of the women of Macao. Only the ones of higher class are carried in portable chairs, like the sedan chairs in London, all totally covered, some of which are quite expensive and magnificent, brought from Japan. But when they go out without them, the mistress hardly differentiates from the maid or slave in their external aspect, all totally covered, but their sherazees are of the best quality [...]. Those women, inside the house, wear on top a blouse of very wide sleeves, called Japanese kamono or kerimono [kimono], because it is the ordinary clothing used by the Japanese, with many being elegant, brought from there, of dyed silk, and others so expensive like those, made here by the Chinese, with rich coloured embroidery and gold [...]."

This kimono must correspond to the quimão28 or baju29 the Macanese women of the wealthy families ordered in non-transparent fabrics, expensive and showily embroidered or garnished with lace. The poorer women wore garments of striped pano elefante30 or cotton. We still saw in Macao, in the 1960s, old Portuguese descendant ladies wearing this garments

When they went out, the women were confined in their sedan chairs, carried on shoulders, and wrapped in their saraças, 31 as depicted in the drawings with which Peter Mundy illustrated his narration and that can be seen in one of the oldest maps of Macao, sketched by Theodore de Bry and published in Germany, in 1598.

Comparing the narration of Peter Mundy with that of another contemporay, the one that the French Doctor Dellon left to us, also in the seventeenth century, regarding the clothing of the women of Goa, it seems that the old bajus of Islamic influence predominated in the Portuguese State of India and Malacca, while in Macao the women of the most wealthy merchants preferred the kimonos of Japanese style or even Chinese. However, this attire characteristic of the Portuguese women in the East, so different from the motherland women, seems to point to the prevalence of the half-caste and various non-European women ethnic groups in Macao. In favour of this hypothesis advocates the fact of that the male attire developing with the time, followed the fashion of Portugal with slight differences of Indian influence like the banianes32 and Moorish trousers used by the men, mainly by the nhons in the blazing summer of Macao. These nhons and nhonhona were the descendants of the Portuguese from the Kingdom, the nhim being the married women, and generally pertaining to a wealthy socialeconomic status. There were also the aias, women also descending from the Portuguese but from a lower social class who were contracted as ladies-in-waiting for the daughters of the wealthier families and who followed them when they got married, becoming a part of the new household. Besides the aias, each child of a wealthy Macanese family had their Chinese ama, who might nurse the child or not, but for whom she was responsible. Many of these amas became part of the important families until their death, if they so wished, some of them being catechized and baptized, sometimes when already quite old. 33

During the eighteenth century, the city being quite impoverished, there started to arrive deportees and soldiers of fortune, unscrupulous people, fleeing from Goa. Thus moral degradation soon followed the economic degradation.

For instance, in the first quarter of the eighteenth century Sir Alexander Hamilton wrote: "There were in the whole city about 200 men [...] and about 1.500 women, many of them quite prolific to procreate children without husbands."34

Other travelers passing through Macao in 1774, for example, the mariner Nicolau Fernandes da Fonseca expressed the same critical opinion.

At the same time, the magistrates Yin Guangren and Zhan Rulin, already mentioned here, who in the eighteenth century visited and stayed for some time in Macao inserted, in a curious xylographed monograph, 35 drawings rich in detail representing Portuguese types and referred to the differences of the social economic status of the Portuguese of Macao, saying: "The men and women of the wealthy families sit and eat (meaning: they lived in the idleness). The poor are soldiers or sailors working on the boats for someone else. The women earn their lives embroidering handkerchiefs and belts and making cakes and desserts."

Among these drawings stand out the picture of a nhonha (ill. l) whose attire must have drawn their attention for its exoticism, which corresponds exactly to the drawings left by Peter Mundy in his book and the clothes used by the Christian Goanese and Malay women, still by the end of the nineteenth century.

The description of these Chinese travelers continue to exalt the luxury and extravagance of the Portuguese who, like the grand Asian masters, continued to travel by sedan chair, palanquin, on foot or on horseback, but always protected by parasols carried by slaves. "The women did the same, followed by female slaves, almost all dressed in a similar way, being only distinguished by the quality of the fabrics." Yin Guangren and Zhan Rulin also wrote that the [Portuguese] men were not allowed to keep at home more than one wife, because the wife would complain to the Bishop and the men would be punished. They obviously refer to bigamy being forbidden. This view is purely sinocentric because a wealthy Chinese could keep in harmony, in his home, various wives. However, the first wife enjoyed the privileges of the mistress of the house and of mother of all the children. The Confucianist morality maintained therefore the monogamous marriage, requiring, however, from the wife an absolute fidelity to the husband but not requiring reciprocity. Thus a Chinese magistrate was shocked by "[...] the Portuguese women not being forbidden to have more than one man." And this because at that time the city's moral and economic misery had reached such degradation that even the householders themselves gave away the wives and their own daughters to foreigners to obtain some profit. The Macanese girls, raised in a certain way in a 'harem' environment, could not have the same moral concepts as those of the Christian girls of Europe, nor the same vision of chastity.

The life of the Macanese women was an idle life, when belonging to the more favoured classes, and liberally Easternized to a higher or lower degree, depending on the respective social classes.

Contrarily to the wealthier nhins and their daughters and closest relatives, the women of the less favoured classes engaged in mutri36 and escarrachada37 needlework and in the confection of desserts and candy, or found jobs as chambermaids. They were also renowned as good chacha38 midwives, assisting the Portuguese families in rivalry with the Chinese midwives.

In defense of the prejudice of Portuguese from the Kingdom and foreigners against the morality of Macanese women, we should bear in mind the poor social and economic conditions in which these women were raised. In addition, and most importantly, we must also consider the kind of behaviour expected of the numerous slaves, both before and after their release from slavery.

If it is true that the Easternized mentality of the Eurasian women led them in a certain way to despise certain values of the European bourgeois classes Judaic-Christian morality. Despite Portuguese husbands being considered jealous and brutal, the truth is that the fault of the dissolute behaviour of some of the women must be imputed to the men with whom they lived. In the middle of the seventeenth century, when the city was impoverished due to the collapse of the trade with Japan, many Portuguese men left Macao and their families behind, with no means of survival. It is therefore easy to blame material misery, together with the 'harem' mentality the Portuguese maintained in the Eastern cities, for the fact that many women, mainly criações and released slaves, led dissolute lifestyles which were criticised by so many eighteenth century travelers.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, liberal ideas from the Kingdom of Portugal spread to the overseas cities and after the foundation of Hong Kong and the influence of Victorian ethics, new behaviour and values influenced Macanese society. The familial morality, so despised in the previous centuries, became a rigorism in high society which the definitive abolition of slavery in 1876 reinforced. The big families which always occurred during periods of bourgeois expansion, started to disappear. The Macanese girls started to enjoy some independence, mainly in relation to marriage, as the dowry was abolished. José Ignácio de Andrade mentioned this in his Cartas escritas da Índia e da China. 39

After the inauguration of the steam boat lines the numbers of European women venturing on long journeys greatly increased and so many more eventually arrived in Macao. Rivalry began to separate these new arrivals from the Macanese women, In fact, not so long ago rivalry increased when there was an influx of Europeans of both sexes into the colony.

Today, when the eurocentrism of the nineteenth century no longer makes sense, when previously the fei-pó40 or ngâu-poó41 was regarded as the fat woman with a moustache, big nose and huge feet by the Macanese women and the local woman regarded as 'pug-face', 'slant eyed' or despised for her creole way of speaking Portuguese, the rivalry still remains, even if not so ostensibly expressed as before. Why?

We know Macanese women of all ages and social classes. We socialize with them and have learned to admire them. Their natural politeness, good taste and elegance in dressing, the amiable and polite manner in which they welcome us into their homes, decorated with furniture and trinkets in hybrid style, are enough to charm us. Intelligent, cunning, or showy when they wish to be, with a well-defined personality and a lot of tenderness behind that mystery peculiar to someone who intentionally does not reveal herself, they indeed hold domain in their households where husbands have surrendered to their rule.

Macanese women so badly known among us, Eurasian, some with no close Chinese ancestry, but whom almost all confound with Chinese and some times insult or despise.

These are pretty and delicate women loved by many European men who married them and took them back to Portugal. Many still looked in the 1960s and 1970s with eyes reflecting their ethnocentric mentality and not able to understand their premature emancipation through the influence of the Shanghai and Hong Kong foreign communities.

Wrongly understood women capable of much love, innocently trusting the ngau 's deceiving words, women that in many cases, in the twentieth century, remained single in Macao like many others who remained single; orphans in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries with the disbandment by men whose only interest was to extract profit and pleasure from Macao.

In the harbour of Macao we heard one afternoon in the 1960s the anguished cry of a child who was leaving:

-"Mammie!"

We saw the contracted shadow of the Macanese woman, wrapped in her red minape trying to hide behind a smile her frustration of being unloved because of being so badly understood.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Manuela Ribeiro

NOTES

1"Quando das minhas mágoas a comprida

Maginação os olhos me adormece,

Em sonhos aquela alma me aparece,

Que pera mim foi sonho nesta vida.

Há ua soidade, onde estendida

A vista por o campo desfalece,

Corro após ela; e ela então parece

Que mais de mim se alonga, compelida.

Brado: -Não me fujais, sombra benina! _

Ela, os olhos em im em brando pejo,

Como quem diz que já não pode ser,

Torna a fugir-me; torno a bradar:-Dina...

E antes que diga mene, acordo, e vejo

Que nem um breve engano posso ter."

Luís de Camões

2Min náp =孕孕 (minape) Chinese dress or jacket padded with cotton or natural silk threads, in Guangdongnese.

3Nhom or nhum = Youngman or master, in Macanese dialect.

Nhonha = Single girl, young married lady, mademoiselle or miss, in Macanese Dialect.

Names given to the children of Eurasian parents.

4TCHEONG-Ü-Lam (Zhan Rulin) - IAN-Kuong-Iâm (Yin Guangren), Ou-Mun Kei-Lok: Monografia de Macau, (Edição de Quinzena de Macau [...], Lisboa) Macau, [Leal Senado] Tipografia Martinho, 1979.

5Biblioteca da Ajuda, Lisboa (Library of the Royal Palace of Ajuda, Lisbon): Jesuítas na Ásia (Jesuits in Asia) - Terminus a quo 1541, terminus ad quem 1649 - Yearly Reports.

6LOUREIRO, Rui Manuel, intro. and annot., Cartas dos cativos de Cantão: Cristóvão Vieira e Vasco Calvo (1524?), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1992.

7PINTO, Fernão Menes, Peregrinaçam de Fernam Mendez Pinto, em que se da conta de muytas e muyto estranhas couzas [...], Lisboa, Pedro Crasbeek, 1614 [reprint: Peregrinação, Porto, Lello & Irmãos, 1984].

8SOUSA, Francisco de, Oriente Conquistado a Jesu Christo Pelos Padres da Companhia de Jesu da Provincia de Goa [...], Lisboa, na officina de Valentim da Costa Deslandes, 1710.

9Biblioteca da Academia de Ciências, Lisboa (Library of the Academy of Science, Lisbon): MSS Constituição do Bispado de Goa, Goa, 1568.

10Mui chai =孕孕(meizi). Younger little sister, in Guandongnese. It is an affectionate way of concealing the situation of a Chinese female child, normally acquired by purchase.

11Biblioteca Pública e Arquivo Distrital, Évora (Evora Public Library and Regional Archive, Evora): Cod. 115, fols 81-89.

12Aitao or aitão = General of the Sea. Official position correspondent to Commander [Mandarin] of the Army and the People for Maritime Defence.

13Cruzado = Old Portuguese coin which circulated from the reign of King Dom Afonso V to that of Dom João VI.

14It was requested from a 'homem bom' ('good man') to be of 'pure blood', older than thirty-five years, married in Macao and with wealth to keep the decorum in his family.

15WICKI, Josef, S. J., Documenta Indica [...], in "Monumenta Historica Societatis Iesu", 19 vols. [to follow], Roma, 1944-1988 [Vols. 1-13 are edited by WICKY alone. Vols. 14-16 are edited by WICKI and GOMES, John, S. J.].

16In the Court of the Magistrate of Mong Há was placed in the eighteenth century an engraved stone, a replica of one that in the previous century (1613 and after in 1617) had been placed in the Senado (Senate) and on which were engraved various Legislation articles concerning both Chinese and Portuguese. One of these articles was precisely the prohibition of the muitsai traffic.

17Criação or creola = Lit.: Breeding, meaning: slave woman of an ethnic group, but not Chinese.

18Hospital for indigent persons.

19Should be noted here the differences established between the criações and slaves. It is possible that they were also employed as maids among the Eurasian women of less fortunate social classes, as still happened in Macao during the nineteenth century. It was from this class that generally came the aias (chambermaids) who followed a wealthy Macanese girl to the husband and/or father-in-law's home, upon marriage.

20Nhim= Little girl, in Macanese dialect.

21Nhonhonha = Plural of nhonha. See: Note 3.

22Ama= Chinese nanny, in Guangdongnese.

23Bicha = Lit.: Animals, meaning: young Chinese woman slaves.

24Afilhada = God-daughter, in Portuguese.

25Timoras = Pop.: woman slaves from the Island of Timor.

26MUNDY, Peter, Travels of Peter Mundy (1608-1667), London, Hakluyt Society, 1919, p.316.

27This 'mythical' attire must be the saraça-baju that, from India passing by Malacca to the Southeast of China, the Asian women used as clothing. It was formed by a cloth from the waist down and a little bodice of a quite delicate fabric to which Linschoten, by the end of the fifteenth century also refers, when describing the wives of the Portuguese of Goa.

28Quimão or queimão = Same as kimono, in Macanese dialect.

29Baju = Outer garment, a coat, a jacket, in Macanese dialect.

30'Pano elefante' = Lit.: 'Elephant cloth'. Was the name locally given to the cotton fabric imported from Goa and whose mark was an elephant. There was white pano elefante (delicate), thick pano elefante (similar to raw fabric), and striped pano elefante.

31Saraça = Colourfully printed shawl or veil, in Macanese Dialect.

32Baniane = Pajama top, in Macanese dialect. Loose top worn by the men at home; sometimes a long tunic similar to the those of the Indian merchants.

33Biblioteca da Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa, Lisboa (Library of the Geography Society of Lisbon, Lisbon): maço (pack) 15 - Diário do macaense António Pereira da Silveira - Espólio de (Bequest of) João Feliciano Marques Pereira.

34ANDRADE, José Ignácio de, Cartas escritas da Índia e da China, nos anos de 1815 a 1835,2 vols., Lisboa, 1847.

35See: Note 4.

36Mutri = Glass beads, in Macanese dialect.

37Escarrachada = Sequins embroidery, in Macanese dialect.

38Chacha or daias = Old women, in Macanese dialect. In old-age the Macanese midwives (Portuguese-Asian mestizo) received this affectionate name that prevailed until the 1960's.

39ANDRADE, José Ignácio de, op. cit., vol.2.

40Fei pó =孕孕 Pop.: a fat, big nosed, big footed... hairy, moustached and, above all, presumptuous woman, in Guangdongnese.

41Ngâu pó= 孕(niu po). Lit.: woman ox. Pej.: ox's wife, or simply, cow; derogative of metropolitan Portuguese woman, in Guangdongnese.

*Ph. D (Lisbon). Lecturer in Anthropology, Instituto de Ciências Sociais e Políticas (Institute of Social and Political Sciences), Lisbon. Consultant of the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation). Author of a wide range of publications dealing, primarily, with Ethnography in Macao. Member of the International Association of Anthropology and other Institutions.

start p. 7

end p.