In the life of Morais we can observe a process of gradual withdrawal from Portugal and from the West in favour of voluntary isolation in the heart of an exotic and hostile world. In 1891, when he had been in Macau for three years as Second Harbour Master, he applied, as was his right every three years -and for the last time- to spend his leave in his home country. In 1898 he obtained a transfer to Kobe as the first Portuguese Consul in Japan and never again returned to Macau.

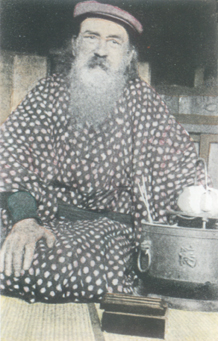

Venceslau kneeling beside the brazier (hibachi) on mats of rice straw (tatami). In front of him, a smoking box (tabako-bon) in which is placed the thin Japanese pipe (kigeru). A good portrait of the "man of the woods" in his exile's cell in Tokushima.

Venceslau kneeling beside the brazier (hibachi) on mats of rice straw (tatami). In front of him, a smoking box (tabako-bon) in which is placed the thin Japanese pipe (kigeru). A good portrait of the "man of the woods" in his exile's cell in Tokushima.

In a telegram dated 10th June 1913 he requested to the President of the Portuguese Republic to grant him immediate release from all official posts, at the same time renouncing his right to a pension. The text of the telegram read: To His Excellency the President of the Portuguese Republic: Venceslau José de Sousa, Naval Officer, in the post of Portuguese Consul in Hyogo and Osaka, Japan, hereby surrenders the Consulship, having been granted permission by the Ministry for Foreign Affairs to return to the Metropolis for reasons of health. For most important personal reasons he wishes to relinquish this post and remain in Japan where he plans to be engaged on a task incompatible with any post in the Portuguese Civil Service, including that of pensioner, possibly even incompatible with retaining Portuguese nationality. For all these reasons he begs most respectfully that your Excellency will immediately deign to accept his resignation as Consul and as an officer in the Portuguese Navy. 1 His resignation was accepted on the 8th of July. Morais had, however, left a few days earlier on the 4th of July, for Tokushima, a small town of 60,000 inhabitants on the east coast of the island of Shikoku, intending to spend the rest of his life there.

The choice of Tokushima implied a life spent in exile, far from any contact with Western culture and civilization. It also excluded any possibility of his integration into the xenophobic society in this small provincial town. Worse still, Morais was the helpless butt of terrible humiliations. The incident of the orang-outang in O Bon Odori is a good illustration of his extremely painful situation in Tokushima. The house in which he lived in Tokushima consisted of a room eight square metres with minute out-buildings on the ground floor and an upper floor of fourteen square metres: Doll's houses [are] not for me: standing up, my head almost hits the ceiling, and 1 have to use the utmost caution not to smash it all to smithereens by a hasty movement. In this description of his exile's cell, Morais inserts a visit to a travelling zoo, the principal attraction of which is an orang-outang from Borneo, in his dreadfully cramped prison behind bars. The description of the ape is a self-portrait of Morais.

It was a cold February day and the keeper had just placed a tin container full of burning charcoal in front of the cage. The orang-outang appeared exhausted, old, an expression of the deepest exhaustion, of a colossal despair, softened by an almost Christian resignation. Apathy and the narrowness of the prison forced him to spend the day sitting or lying down. He held in his hands a hammer left by the keeper as a toy, and which can be taken as a symbol for the pen of Morais the writer. After studying the hammer for a while, the orang-outang dropped it, disappointed. Then, when he decided to pull some straws from the bedding on which he lay and chew them, the keeper screamed angrily at him, threatening him with an iron bar he had just withdrawn from the brazier. The poor animal, who had already experienced the red hot iron on his skin several times, reacted with terrible gestures and dreadful expressions (...) expressions of hatred, of impotence, of hallucination. Moments, however, he slid back into his usual attitude of uncomplaining martyrdom, while the onlookers laughed, amused. Morais interpreted the Malayan name of orangoutang as 'man of the woods'. For the inhabitants of Tokushima, Morais was a kind of 'man of the woods' owing to his appearance: broad shoulders and a long hairy beard hiding half his face.

In the presence of the 'ape-man' the sensitivities of the Japanese lapsed: For Chiyo-Ko [sister of Ko-Haru, his second Japanese wife] I am the monkey... with whom, having lost the fear due to all exotic animals, her imagination allows her liberties of conduct which she has never taken, nor would she dare to take, with her peers, the Japanese". (0-Yoné e Ko-Haru, p. 146 ff).

Portrait of O-Yoné, first Japanese wife of Morais. She was married at the age of 25, when Morais was 46.

Portrait of O-Yoné, first Japanese wife of Morais. She was married at the age of 25, when Morais was 46.

What can have led Morais to take such a serious step as the retreat to Tokushima? This issue was already puzzling his contemporaries. In October 1933, the Governor of Macau asked the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Tokyo whether Morais was still sane. Tokyo commissioned a chief constable to obtain a certificate of mental health for Morais. After a personal conversation with him, the Constable finally considered him to be normal. 2

For the Japanese authorities also this Portuguese man who chose of his own free will to live in Tokushima under extremely difficult conditions, was an enigma.

After Japan declared war on Germany on the 23rd of August 1914, there were those who suspected Morais of being a spy. He was therefore interrogated by the Military Police and his movements controlled for some time.

Since Morais never openly explained the reasons for his behaviour. either in his writings or even in his private correspondence, Portuguese and Japanese biographical researchers tried very hard to decipher the mystery, and came the unanimous conclusion that it was his love for O-Yoné, his first Japanese wife, that compelled him to resign from his official post and retreat to Tokushima.

O-Yoné Kukamoto was born in Tokushima. She had been sold by her impoverished parents to a geisha house in Kobe. She knew how to sing, dance and play the shamisen. According to his Japanese biographer, Matsumoto. Morais must have met her in September 1898 in a low-class night-club district in Kobe, where clearly defined frontiers between the art of geisha and prostitution did not exist. In April 1899 Morais freed O-Yoné, paying an indemnity to the proprietor of the house. In 1900 when she was twenty-five he married her according to the Shinto rites. O-Yoné died of a heart attack in August 1912. Her ashes were transferred to Tokushima, Morais assuming the costs of the shrine.

Venceslau de Morais and Japanese girl Ko-Haru. In the front row, Saito Yuki, the mother, is seated.

Venceslau de Morais and Japanese girl Ko-Haru. In the front row, Saito Yuki, the mother, is seated.

The romantic legend of the great lover who renounced the honours and comforts of a bourgeois life in order to live near the mortal remains of his wife arose from the chapter entitled "Venceslau de Morais" in Visões da China (Images of China) by the author Jaime do Inso (1933), and was enlarged upon by Ángelo Pereira and Oldemiro César who, in 1937, published an article "The loves of Venceslau de Morais" which stated that: The deep wound [of O-Yoné's death] that had just broken his heart, led him to abandon Kobe and settle in Tokushima, where the ashes of his beloved wife rested. He also abandoned his Consular post; he resigned from being an officer in the Navy and hastily and cheaply sold off the many books of his well-chosen library, with all his belongings, except for some of particular personal value. Armando Martins Janeiro goes more deeply into this interpretation, seeing his retreat to Tokushima as a significant step in a long progress of assimilation into Japanese culture: Venceslau moved to Tokushima to live with his dead wife... It is common in Japan for the widow or widower to sell all their personal belongings and go to live beside the ashes of their spouse. Venceslau did no more than follow the old Japanese custom. Her portrait is placed on the family altar, the butsudan. The first cup of tea in the morning is for her soul, for her the first spoonful of rice from the cooking pot. Never a present is opened (...) without first placing on the butsudan the portion which belongs to the beloved soul, while murmuring "Yoroshiku o-agari kudasai" meaning 'deign to eat with pleasure'. With his many years in Japan and his sensibility towards everything Japanese, Morais had assimilated this poetic belief. Only this can explain his departure for Tokushima and his devout and serene life of poverty in the small provincial town, where not a day passed without visiting O-Yoné in her little shrine for Chionji. (0 Jardim do Encanto Perdido, p. 145).

Although there is a certain fascination in the discovery of the theme of cause and effect (death of O-Yoné: resignation and voluntary exile) when reading O Bon Odori em Tokushima, we feel that a different interpretation can be made. Clearly the shrine of O-Yoné had a certain bearing on the choice of a place to which to retire, but there are plenty of indications in Morais' writings, as well as his biographical data, that call for another explanation for his resignation and subsequent withdrawal from the western world. Nowhere in his literary work or correspondence does Morais suggest, even vaguely, that O-Yoné's death carried any weight in his resignation. Furthermore, in O Bon Odori em Tokushima he tells us that for a long time he carried on a discussion with his doppelgänger about his of residence in Japan: We pondered the matter at great length, various plans, various halts flitted through our minds; we discussed pros and cons until one of us cried out to the other something like: -fly from the living; go to Tokushima; be near this shrine with the memories of a name that is dear, that will give your nostalgia substance. If the desire to spend the rest of his life near the tomb of O-Yoné had been the reason for his resignation, this lengthy cogitation about a future place of residence makes no sense.

Japanese biographical research has revealed a number of facts which, though they cannot always be documented, throw doubts on this myth of a sacrifice for love. Whenever O-Yoné needed care, Morais would ask her sister, Yuki Saito who lived in Tokushima, for help. Yuki Saito usually brought her nineteen-year-old daughter Ko-Haru with her. There is every indication that Morais, even before the death of O-Yoné, felt strongly attracted to this girl (Tsukuda: p. 117). The Saito family was very large and poor. Ko-Haru's father worked as a cook on a boat that plied between the islands of Honshu and Shikoku. According to Japanese biographers, Morais' infatuation for Ko-Haru did not go unnoticed by Yuki: When O-Yoné died she may have hoped to marry her daughter to the Portuguese Consul in Kobe.

However, a third woman came on the scene to complicate the situation: Den-Nagahara, who appears to have played an important part in the life of Morais at the time of his resignation. After the death of O-Yoné, Morais lived with this attractive twenty-five-year old woman from Imaichi, near Matsue (Shima-ne-Ken, Izumo).

During the months they were living together, Yuki Saito tried in vain to get him to visit O-Yoné's shrine. In April 1913, Morais sent Den-Nagahara to Matsue with the mission of finding a house there in which they could live together. (Hanano, Matsumoto).

Tokushima: the shrine of O-Yoné, first wife of Morais

Tokushima: the shrine of O-Yoné, first wife of Morais

Matsue was of special interest, having at one time been the temporary residence of the late master of Japanese exoticism, Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) in whose life and works are many similarities with those of Morais. While writing of Hearn, Morais seems to have been relating his own life: from infancy Hearn had been a victim of his peers of the white race; we should also bear in mind that his delicate sensibility suffered from the spiritual vulgarity of the times seen in Western societies. Having arrived fortuitously in Japan, he settled here in this land that enchanted him, married a Japanese woman, took Japanese nationality, identified himself as far as possible with the Japanese soul (Cartas do Japão, vol. III). The last year of Hearn's life seems actually to anticipate Morais' exile in Tokushima: Of a frail physical constitution, undoubtedly still affected by the difficulties of his youth, Koisumi [Hearn's Japanese name] had been ill for some time. He lived a secluded life in Tokyo in his Japanese cottage surrounded by its delightful garden. Of a nervous and eccentric temperament and tired of the social life, he absolutely refused latterly any connection with the large foreign colony in the Metropolis.. (Cartas do Japão, vol. II, p. 221).

Morais admitted that he owed much of his literary development to Hearn: I have referred many times to Lafcadio Hearn, the greatest impressionist talent to write about Japan in a European language. In certain cases they are rather more than simple references, for in his books I have made valuable discoveries about Japanese folk-lore, some of which I have made public in my uncouth prose. I must add that I consider this plagiarism forgivable, even commendable, in view of the task I have undertaken of presenting my readers with what strikes one as most pleasing and interesting in the study of this country and this people. I was also swayed by the following reasons: the scant public acquaintance with Hearn's works in our literary world; the amazing profusion in these works of passages of indigenous folk-lore, thanks to the unusual circumstances of the author's existence; his remarkable knowledge of the Japanese language and classical literature; and his gift of great sensitivity as a research-er. (Cartas do Japão, vol. III). Had Morais chosen to settle in Matsue, he would have become in everybody's eyes the literary successor to Hearn.

The choice between Matsue/Den-Nagahara and Tokushima/Ko-Haru seems to have been difficult. According to Matsumoto, the negotiations effected with the Saito family on the 4th of July in Tokushima helped him reach a decision and when, a few days later, he returned to Kobe, he went with the firm intention of ending the relationship. On arrival he must have found a letter from DenNagahara telling him that all was ready for their future life in Matsue. She herself intended opening a tobacco shop to improve the financial situation of the new house. In his reply, Morais would have begged her pardon for changing his mind (Matsumoto). Everything points to his never seeing her again.

In the following suggested interpretation we do not seek to explain the extremely complex matter of Morais' retreat to Tokushima, but rather to open a new path to an understanding of it. We start with the premise that we need to distinguish between the real, factual life Morais lived in Japan and his fantasy life as narrated in his writings. Of his real life we know little. Anyone going through the private letters addressed to family and friends will be surprised as much by the paucity of this literary adventurer's correspondence -three or four thin volumes of letters and cards- as by its unrevealing content as regards his life in Japan. During the years of Cartas do Japão3 (1902-1913) he was living with O-Yoné, but there is no reference to her either in his private correspondence or in his literary work of this period. The most astounding thing is that not even his beloved sister, Francisca, with whom he corresponded regularly, knew of O-Yoné's existence. When she died he merely sent a postcard with the news of the death of a "domestic servant" that had greatly upset him! This is the only allusion to O-Yoné we have found in his letters over the period of fourteen years of co-habitation.

Tokushima: the shrine of Ko-Haru, second wife of Morais

Since Morais was the only Portuguese man living in Japan, it was easy for him to hide from readers, friends or family, anything he did not want known. Why, in his private correspondence did he consistently avoid mentioning his two marriages in Japan or his private life in general?

In his literary work, also, Morais avoided mentioning any sexual relationships in his life. The only passage alluding to a love affair is to be found in Saudades do Japão 1894 (Traços do Extremo-Oriente p. 164 f.) Dai Nippon 1895 is indeed a hymn of praise to the charm of Japanese women admired as a "living work of art", but Morais does not mention any specific love affair of his own. What mattered to this "decadent romantic" was giving literary expression to his fantasy life that is to his inspiration, the driving force of his life. In the autobiographical passages of his narratives he presents himself as a solitary bachelor living "in exile" outside Japanese society. Obviously, in Morais' hierarchy of values, celibacy occupies a prominent place. As he wanted his readers to see him as leading a frugal, monastic life, guided exclusively by moral and spiritual values, he avoided speaking of what he considered the imperfections and "baseness" of his real life. And he did all he could to avoid any discrepancy between his letters and his literary selfportrait.

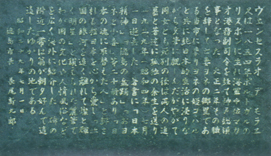

Tokushima: details of the memorial to Venceslau de Morais

It would seem that Morais wanted to impress his readers not only with the uniqueness of his life but also with his moral superiority. When he recounts in detail his role as orang-outang in Tokushima society, he does it not so much to compose a picture of a European in a backward and xenophobic town in the interior of Japan, but to underline the importance the role of victim and martyr assumes in his fantasy life. In Morais' ethics, deeply imbued with Christian values, only profoundly felt and heroically accepted suffering ennobles the individual, surrounding him with an aura of divinity (see O-Yoné e Ko-Haru p. 42). The intensity of pain, sadness and fear visible in the orangoutang's look transforms him into the protagonist of an epic poem: What a look!... In that look, what a depth of profound sorrow!... What a poem of epic anguish!... Just to see it, just to see it as I saw it, it is possible to understand such pain!... This affinity of Morais with the orang-outang does not end with the scene of the red-hot iron. The more closely he observes the "prisoner" the more familiar do its gestures become: Oh, there was no doubt, it was me!... I could see myself in the presence of that already legendary character well known as Zé Povinho that the great artist Bordalo Pinheiro so often used his pencil to sketch in the papers twenty or thirty years ago. I then had the clear impression of watching a humble man of the people, a Portuguese carpenter who had, in mockery, been allowed to bring the tools of his trade with him, condemned without trial to life sentence, until consumption... should free him!... The ape, just like the Zé-Povinho carpenter, is an allegory for the Portuguese people, exploited, devoid of rights, in other words, the working class. The fact that the protagonist in O Bon Odori em Tokushima, Morais-Joe Nobody identifies himself with the ape allows us to conclude he had come to consider his destiny as a symbol of the destiny of the people of Portugal.

From a biographical point of view, Morais settled in Tokushima voluntarily and without coercion. From the literary point of view, however, the slow death in the prison of his little house in Tokushima was the direct result of living conditions in Portugal where, as did so many others, he lacked spiritual bread, so, logically, they emigrate like the poor field-labourer who, lacking bread for his lunch, emigrates to far-off places looking for sustenance. (O-Yoné e Ko-Haru). In his private correspondence, Morais puts this idea in concrete form, blaming the powers-that-be as well as production difficulties in Portugal for his "exile": Our civilization is sinking more and more into vulgarity, egoism, insipidness. I can understand that the rich, the industrialists and even politicians love it in the interests of their own pockets but whoever is not like that and needs to live with feeling, will of necessity have to adapt himself in simplicity to primitive civilizations where there is still a basic ingenuousness, goodness and picturesqueness that ours now lacks.

The three characters featured in his literary work are himself, though idealized, mythicised; Japan equally mythicised - the title of his masterpiece of his years in Macau is Dai Nippon- and, paradoxically, Portugal. Portugal, apparently the great absentee in the work of an author who seems to have substituted his true homeland -Portugal- with a homeland of choice - Japan. The paradox is solved by remembering that Morais in fact rejects the country of the English Ultimatum of 1890 and the following decades, but venerates the Portugal of the time of the discoveries and the underlying exalted image of the country. Discovering in himself the energy and daring of heroic Portugal, he addressed his work to possible Portuguese fellow-thinkers who would understand the symbolism of the absence of Portugal, and who would be able to capture the message of his exile in Tokushima's nostalgia. Having chosen Tokushima as the stage, or altar, on which to celebrate his nostalgia for the past grandeur of Portugal, the fact that Morais never again left this little town between 1913 and 1929, even to travel in Japan, acquires some significance. Equally significant is the fact that, so far as I know, Morais never showed any desire to see his work translated into English or any other language, including Japanese.

Pedro Vicente de Couto, Morais' best friend in Japan, remembered an enlightening conversation reproduced in detail by Matsumoto. Couto was from Macau and employed by the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank in Kobe. The affection felt for him by Morais is clear from these lines written to Dias Branco on the 17th April 1913: Couto is the best of all the Macanese here, sober, honest and hard-working. You have done much more for him than all the others to whom I recommended him. For my part, thanks very much. (Osoroshi p. 46) Couto was present at all the important happenings in Morais' life, for example, his marriage to O-Yoné, and her death. Besides this, he often visited him in Tokushima. He can therefore be considered a trustworthy source of information.

In the conversation which appears to have taken place shortly before the end of 1912, Morais mentions that he will be fifty-nine years old in 1913. Speaking of the Chinese calendar which considers the age of fifty-nine as the end of the first cycle of human life (in Japanese: kanreki) and sixty as the start of the second cycle, Morais confessed that he thought of the passage from the first to the second cycle (30th of May, 1913) as a new beginning. He therefore wanted to resign from all official duties so as to be able to dedicate himself entirely to another task for as long as his health permitted. Couto understood that Morais had unshakably decided to consecrate himself exclusively to literary creation, and this was confirmed by his friend: he wanted to sacrifice his social life in exchange for total fulfillment as a writer.

The difference in dates between his birthday (30th of May) and his resignation (10th of June) is explained by the fact that the 10th of June was the day of Camões' death. In choosing this date to send his telegram of resignation, Morais indicated the nature of the high goals which would govern the second cycle of his life: he aspired to produce literary works of the highest national significance. His sixtieth birthday and the telegram of resignation are thus symbolically interwoven.

For Morais, the source of poetic inspiration in contemporary national literature was nostalgia. It is quite possible that he had known about Teixeira de Pascois and the 'Saudosismo' (Nostalgic) movement. In any case, with the "moral suicide" performed on his sixtieth birthday, Morais believed he had reached a higher level, a spacial and temporal distance, in regard to his own life. The conditions necessary for the enjoyment of absolute nostalgia were finally assembled. After two years of solitude in Tokushima, Morais was able to state: I have been living for years in the world of nostalgia, not in the other one. It is the exact mean between the earth to which I no longer belong, and the world of death which I am approaching. (O Bon Odori em Tokushima, p. 283). He also connects the "state of exile", unique in its radicalness, with the hope of creating poetical works of nostalgia which will equal or even surpass in "magnitude" (Jaime de Inso) the masterpieces of Portuguese literature. The "magnificent subject" (Inso) of O Bon Odori em Tokushima is his life in this town after his "moral suicide": What daring! What incredible daring, for a fair skinned man, a man from the countries of the white race and, above all, a Portuguese! (O Bon Odori em Tokushima, p.105)

Morais wanted to experience absolute nostalgia. He could have chosen any little Japanese town in the interior, but he chose Tokushima because the tomb of O-Yoné would act as a stage on which to celebrate the rites of the cult of nostalgia. Only after death could O-Yoné and Ko-Haru enter his literary works, not as wives or lovers but as symbolic materializations of the nostalgia they represented for the whole of Morais' past life: My mortified mentality can be compared to a great octopus bearing enormous tentacles, which extend in all directions in an anxiety to apprehend, to embrace everything that talks to him of the distant past. I have learned to love them, the dead, without distinction of race, without distinction of merit; moved only before their shrines... I feel nostalgia for those I loved, nostalgia for those I hated, nostalgia for those I saw, nostalgia for those I heard, nostalgia for everyone and everything... (O Bon Odori em Tokushima, p. 124/250f).

Eduardo Lourenço asserts that one of the characteristics of Portuguese culture in the nineteenth century is the desire to return Portugal to its ideal grandeur, so rejected by the material circumstances of its political, economic, social and cultural mediocre reality. That is to say, in literary terms, an obsession to create a movement or a work in which this symbolic renewal is achieved. The life and work of Morais constitute one of these efforts to recreate a soul - in eighteenth century mould. In March 1878, on the occasion of the commemoration of the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of the sea route to India, Morais launched in Kobe a "sacred appeal" to the people of Portugal: Awake, Portugal, awake - it is time... Awake Father!... What has come come over you... sleepy head!... to stay asleep for I don't know how many thousand days running!... Awake Father, for the sun has risen and today is a feast day for the family!... Awake, rise up, take heart and love your past, your heroes, your Camões.... In this way Morais involves himself wholly, to quote again from Eduardo Lourenço, In the long and as yet unfinished tradition of Ulysses, intellectuals in search of a country that we all possess, without succeeding to adjust therein the plausible dream we need to face the bitter illusion of reality. 3

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Venceslau de Morais, Dai Nippon-O Grande Japão, Lisbon, 3rd edition, 1972.

-, O Bon Odori em Tokushima, 2nd edition, Oporto, Companhia Portuguesa Editora, 1929.

-, Cartas do Japão, vol. II: "Um ano de Guerra (1904-1905)", Oporto, Livraria Magalhães e Moniz, 1905.

-, Cartas do Japão, vol. III: "A vida Japonesa (1905-1906)", Livraria Chardron de Lello & Irmão, Oporto, 1907.

-, Osoroshi, Lisbon, V. Abrantes, 1933.

Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido ou a aventura maravilhosa de Venceslau de Morais no Japão, Oporto, Manuel Barreira, n. d.

Eduardo Lourenço: O Labirinto da Saudade, Lisbon, Publicações Don Quixote, 1978.

Alvaro Manuel Machado: O Mito do Oriente na Literatura Portuguesa, Lisbon, Instituto de Cultura e Língua Portuguesa: "Biblioteca Breve" Collection, vol, 72, 1983.

Helmut Feldmann: Wensceslau de Morais (1854-1929) und Japan. Munich, Aschendorffsche Verlagsbuchhandlung, "Portugiesische Forschungen der Görresgesellschaft" Collection, second series, vol. 6, 1987.

NOTES

1 Quoted by Armando Martins Janeira: O Jardim do Encanto Perdido.

2 Quoted by Armando Martins Janeira: op. cit., p. 273.

3 O Labirinto da Saudade, p. 93.

*Ph. D. in Romance Philology; lecturer at the University of Cologne.

start p. 191

end p.