THE JAPAN OF VENCESLAU DE MORAIS

The books written by Venceslau give an intimate idea of his impressions and his life in Japan. But despite this intimate approach, there is the feeling that certain subjects are missing, and that he does not give us the full intimacy of his feelings.

Armando Martins Janeira, in O Jardim do Encanto Perdido

The work of Venceslau de Morais deals almost exclusively with one subject: Japan. He also wrote about Siam, China and Macau, but Japan was without doubt his favourite topic: Dai-Nippon, the Great Japan!... Once again, fellow country men, I have in hand my favourite subject.

Japan was his subject, but he was fully convinced that his strength as a writer came from Portugal - his Latin temperament, and his inquisitive, critical, compassionate eyes, the foreigner caught in the contemplation of the most delightful of spectacles, that his pen described with all the colour and lilt of his mother tongue. 1 Venceslau was deeply attached to his country but, beyond this, he felt a passion, a deep love for Japan, that reveals a passionate life and a thorough understanding... of the character, customs, life and wisdom of the Japanese people. Some details demonstrate his closeness to the Japanese and a perception and highly tuned sensitivity towards things Japanese. 2

Venceslau de Morais aged 49 (1903)

Venceslau de Morais aged 49 (1903)

His works include a variety of topics: whoever has patiently read my works will have noted that... I have been entertained in writing light, sentimental, impressionistic descriptions of the Japanese landscape, art and the Japanese woman; and I can imagine that to many this association of ideas will have appeared incoherent. Concerned with a wide variety of aspects involving culture, life and the land itself, Venceslau de Morais reveals his taste and understanding for the traditions, habits, customs and the whole culture of a people whom he loved deeply: it is interesting to note in Venceslau de Morais, as we read into his works, how varied and deep is his understanding of the Japanese... and a serious, systematic approach is not his style as a writer: "the only books for me are those composed of scattered notes, daily jottings and brief impressions, etc".3

Scattered notes, jottings on paper and impressions. Travel stories or chronicles, descriptions of landscapes, itineraries, the whole work of Venceslau de Morais is a report, like a diary or book of memoirs, which narrates events, outlines considerations on a wide variety of topics, and tells stories and legends. Written randomly, the result of the pleasure he took in writing, talking and speaking: speaking in which I am the first to recognise the vociferousness of topics dealt with at the whim of a Bohemian pen, with the lack of ceremony of those who ignore whether the time is ripe or if they are tedious... the work of Venceslau de Morais is the meeting of East and West, the confrontation between two worlds where union is possible although Venceslau himself recognises on many occasions the impossibility of total integration, because of the incompatibility of race, countenance and sentiment, with whom a pact is impossible, and even an approach itself becomes suspicious. But as Celina Silva observes in the preface to Dai-Nippon: the intimacy of Venceslau de Morais' understanding of the Japanese people illustrates the possibility of a harmonious synthesis of Eastern and Western values. The impossible was overcome. The barrier faded. The vast, rich, harmonious and original work of this Latin fascinated by the Great Japan, and only this work achieved that which his long and expectant life and travels in Japan denied him: his full integration in Dai-Nippon! Today, and ever more! 4

Martins Janeira explains in O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, that the spiritual biography of Venceslau can be sensed in his works; but the same is no longer possible if we try and look for his real biography, his daily life-style and routine. Venceslau did not leave us with his biography; Venceslau's works are not essentially biographical, although they do give descriptions of a biographical nature, intimate impressions, small revelations, randomly written notes. The writer's work as a whole is, rather than a literary discourse, a description of the daily life of the author, his impressions, memoirs, his life story, related in small chronicles or letters but in which, despite his tone of confidence, his most inner sentiments are not revealed; Venceslau speaks of himself, in talking of Japan; he describes his life in Japan by describing Japan and its people as well.

What is important is to observe not the life as a specific whole, but the meaning attached to it by the narrator. To write a life story is not a question of chronologically presenting the events experienced, but expressing a feeling for what has been experienced; and what it is interesting to observe is the way in which the subject-narrator tries to tell his story as an on-going, unwinding whole, of a series of events, like a desired or selected itinerary. Through the eyes of the narrator we look not at him but at the world he describes, or, more precisely, at 'his world'. The experience and interaction between the 'I' and the 'world' reveals to us a 'particular I' and 'a personalised world', that is a given universe personalised in a specific way, revealed through the formation of a specific subject. 6 In examining the works of Venceslau de Morais from a biographical perspective, the aim is to observe his life in Japan, particularly the view transmitted to us by the author. It is not an attempt to reconstruct the author's life in Japan, to chronologically describe an individual experience; the aim is to observe his life and travels in the country and his view of the Japanese world, that is, trying through narrative discourse to understand his 'experience': the world which he describes is 'his' world.

This is a short study of the life of Venceslau de Morais in Japan based only on his written works concerning Japan, covering 'periods' or more precisely 'spaces in time' corresponding to a specific 'time' and 'space' according to the context in which his works were produced. Although Venceslau de Morais frequently uses the same topics and the same subjects, his work does, however, develop as a result of new interpretations and views, and because of greater detail made possible through long years of acquaintance. It is this development in time and space that we propose to observe in selecting three periods that are significant because in a certain way they represent a break with previous periods, periods which are related to a specific time and space, in which the works were produced:

Firstly, we will look at an initial period, or 'period of travel', the 'space in time' when the author lived in Macau (1889-1899), when Morais' knowledge of Japan was the result of his travels throughout the country;

We will then move on to a second period corresponding to the 'space in time' in Morais' life in Japan when he had official responsibilities as the Portuguese Consul in Hyogo and previously in Osaka and Kobe (1899-1913);

Finally, we will examine a third period or 'space in time' when he lived in Tokushima (1913-1929) when he decided to withdraw from official life and permanently adopt a Japanese life-style.

THE INITIAL PERIOD: SAUDADES DO JAPÃO7

Personally, I must confess that in these farflung corners of the world, where destiny has led me, picking out Japan in particular, so attractive because of its own originality, it is the primitive landscape and the intimate countenance that attracts me; and the more I feel part of these people, the more I feel Japanese, the more I am bewitched by this undefinable strangeness, which is, when all is said and done, the best of what I have met with on my travels.

A period of travel: Venceslau de Morais is the fascinated traveler who randomly describes his impressions while traveling and where he includes the enchantment inspired in him by Japan:

There is an undeniable pleasure, although bitter, in listing in the mind, recording all that once enchanted us. These pages have no other explanation; they reflect a satisfaction, almost a personal need; and certainly they will not affect the reader with the same interest as they do me, for whom they are suggestive not because of these pallid sketches, nor these random notes, but because of the memories they recall. (Traços do Extremo Oriente, chapter "Saudades do Japão", 1894). Dai-Nippon is included in the works produced during this period. Written, like the Traços, after his travels to Japan, his literary production during this period is found in his travel chronicles. He was a seasoned traveler, but particularly in Japan. He first proved himself a writer in Japan, because it is here that his fascination was inspired by the country and the Japanese people, and that his writing is at its finest, leading him to attempt to transmit and communicate all his feelings, enthusiasm and passion.

Bust of Venceslau de Morais in a garden in Kobe

Bust of Venceslau de Morais in a garden in Kobe

Dai-Nippon, published in 1897, by the Geographical Society of Lisbon, is also the result of travels to Japan. Martins Janeira, in referring to Dai-Nippon and the Relances, says that: all that is in these books is quite dead today, with the exception of some landscapes which are picturesque and of local interest... if they possessed any scientific value, it has been entirely lost as a result of recent studies on Japanese culture and ethnography. 8 He criticises them for their primitive approach, the choice of material, the awkward style, and the lack and confusion of opinions: the hybrid tone of books relating facts and with subjective narrative, immediately raises reservations with regard to the objective credit they merit. 9 However, despite this relating of facts and a subjective tone - particularly the latter, not only in these books but throughout his works10- Venceslau de Morais is sensitive in approach and has a perception of detail in describing the life and people of Japan. In particular, he reveals his world and his view of the Japanese world. Furthermore, and as Jorge Dias11 observes: it is, however, in Dai-Nippon that one of the great prose writers of the Portuguese language is revealed, in the best travel book published in Portugal since the era of the Discoveries.

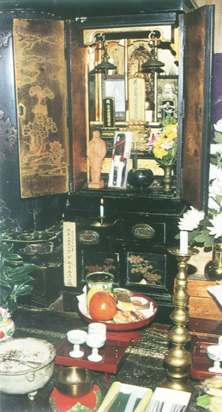

Altar dedicated to Morais in the Temple of Tokai (Tokushima); note the small statue of the writer and the photograph of O-Yoné

Altar dedicated to Morais in the Temple of Tokai (Tokushima); note the small statue of the writer and the photograph of O-Yoné

Altar dedicated to Morais in the Temple of Tokai (Tokushima).

Altar dedicated to Morais in the Temple of Tokai (Tokushima).

In the initial period of his travels, while staying in Macau, Venceslau de Morais visited China and Japan several times. He began to write short chronicles, impressions of life in Macau or about his travels in China, where he gradually became familiar with the people and Chinese society. But he never felt a true fascination for China and his disenchantment occasionally leads him to use a rather harsh tone. He has little to say by way of praise about China and its people. He compares Japan with China and the disenchantment is greater: the contrast was truly surprising in a person who had lived for so many years in China, used to the monotony of Chinese decoration, the dryness of its coastline, the filth of its villages, where a shoal of people flounder, ugly to a degree, hostile to the European to a degree, and which Loti named... the yellow hell.

From his very first visit, Japan fascinated him: I arrived in Japan. I loved it to the point of delirium, I drank it as one drinks a nectar; this enchantment sharpens his interest in Japanese life and society, its traditions and ancient cults, its people, the Japanese woman, the landscape. There is an abyss between China and Japan, comparable to leaving a cave and walking into a garden.

Travels: destiny led me to the land of Japan. Japan, that I visited some months ago, for the second time in my life. A thousand memories of Japan still jostle in my mind; they fill me with that nostalgia which comes whenever anything is lost, that has passed never to return; in this case the nostalgia is ever deeper, because it involves the charms of a country more attractive than others, because of its suave landscapes, the pure blue of its fortunate sky, because of its people, interesting because of legendary tradition, because of their temperament, because of their manner nowadays; and with whose intimate way of life, in the solitude of its villages or the bustle of its cities, I associated my Bohemian existence for many a day.

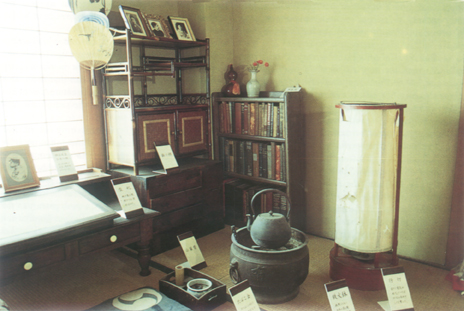

Venceslau de Morais Museum in Tokushima.

Copy of his room with personal belongings.

Venceslau de Morais Museum in Tokushima.

Copy of his room with personal belongings.

Bohemian existence: in his detailed descriptions of the chayas, the geishas, the saké served by "gentle musumés", the sound of the shamisen played by a geisha. The period when he traveled in discovery of Japan unfolds, when his fascination for the country, its people, Japanese women -there is no woman more delicate than these musumés- is manifest, right from the very moment when he first sets foot on Japanese soil. He gives us a detailed description of one of his visits to a chaya, where in the company of O-ko-Yoné, his geisha, (whom he called "Senhora Baguinho de Arroz", [Mrs Grain of Rice]) he spent long hours attracted by the gentleness of her company... desirous of interweaving the name of a woman into the golden web of my impressions:

The rustle of silk, the smack of wood against wood, the muffled sound of shuffled footsteps; and O-ko-Yoné-san, Senhora Baguinho-deArroz, leaving her sandals at the entrance to the room, came to me, a smile on her lips, like a tiny household fairy. A gentle apparition!... Gentle, but not only gentle. Her dusky colour, slightness, that ever sweet, cherry shaped mouth, jet black hair and eyebrows, brown eyes and the graceful movement of a gazelle. She arrived with the tool of her trade in hand (the instrument with which she earned her daily bread, if indeed she ate bread), the shamisen, the native guitar. She knelt. One by one the chords were tuned, releasing isolated notes. A murmur left her lips. Her fingers touched the strings in a thousand tiny movements. She fixed her gaze on me and smiled. There were brief interruptions, to smoke her silver pipe, to dab her lips with the fine silk handkerchief.... She finally ended her singing in a soft harmony; and the chords of the shamisen trembled as they were struck by the ivory spatula, wielded by her nervous hand.... They served me dinner; exotic delights... O-ko-Yoné-san did not eat, as custom dictated; she took only sake, the local rice wine; and in friendly fashion, every now and again, we exchanged cups, which in this country is a sign of friendship.

His incursions into Bohemia were not restricted to chayas and the company of geishas. In Tokyo, he visited Yoshiwara, accompanied by Edmond de Goncourt, whose book Outamaro, he was then reading:

A visit to Yoshiwara by night, the famous brothel, which, believe me, I approached full of a vague respect and undefinable emotion.

Do not find this odd. A few days before I had browsed through a book by Goncourt, Outamaro, a study of the painter Outamaro, some of the most exciting pages on Japanese life that I know of;... and it was to Yoshiwara that I went, and when I arrived in a rick-shaw, with only the poor coolie for a guide, who in a gesture pointed out the bright lights standing out against the darkness of the night, like a stupendous magic apotheosis.

Venceslau was so fascinated by Japanese woman that he dedicated many a page to her, the musumé, throughout his work; it is not exactly the beauty of the Japanese woman that fascinates him but rather her delicacy, her gestures, her gentle nature and her kind, and at the same time submissive, appearance:

The charm of the musumé is in her company;... but the charm of the musumé is in this, as in everything; it is in the exotic nature of her individuality, of her whole way of being and feeling; her slightest gesture alone is for us a surprise, a revelation. A sentiment he reiterates: the charm lies particularly in her gestures; for example, in the way she curves her hand when she raises the little teacup or the faichis to her lips, when she moves her fan, when her fingers play the guitar, when she embroiders; in the leg she folds on the silk cushion; on the foot that arches, or that toyfully plays, dangling and naked, or which she fits into the sandal with a special gift for touch in those tiny, clearly defined fingers.

And there is also the musumé's clothing -her kimono, with the obi, this wide band at the waist, with its colours and the shapes it adopts on the body of a woman- which charm him and about which he gives us some beautiful, sensual descriptions:

there are the kimonos and obis, in unimaginable colours, which lovingly clasp the shape of the body. Kimonos, with overlapping bands on the front, leaving bare a delicious acute angle (never has geometry been so poetic!) at the neck and breasts; leaving the arms bare, in the finest of sculpture, emerging from the undulating curves of the long pagoda sleeves; then falling in gentle folds, these kimonos, fall in a bell-shaped sheath, until they kiss the heels, allowing a glimpse of white naked feet, held by crimson velvet clasps within the black lacquered sandals. The obi is a different colour, affording the beauty of contrasts, and within its overlapping folds the Japanese girl keeps her little purse, her amulets, the pipe in its ivory case and a thousand tiny trivialities for her use; but the obi is there for a particular aesthetic reason, which escapes us, unless we interpret it as that which makes the musumé look vaguely reminiscent of a large exotic flower, an orchid from a garden of dreams, with curling petals standing out from the stem, trembling in the breeze which are the enormous ties which fall from the waist.

He speaks little of the Japanese man, considering him aesthetically far inferior to the woman, and, humorously, he observes: casting an eye on these latter subjects, we come to an interesting conclusion, that Japan would be much nicer if there were no Japanese men; and his presence is only forgiven for their merit, which no-one can deny, of producing daughters, of unwittingly contributing towards perpetuating the musumés.

Venceslau is enraptured not only by the charm of the musumé but also by the landscape: "whims of scenery that no-one can imagine", the people: "this great tribe of delicate people, known as the Japanese family", art: "the originality of Japanese painting, which to the European who does not know how to view it, or does not wish to view it, appears ridiculous". All these inspire him to find descriptions.

He covers both countryside and town. He goes to Nikko: "Nikko, prodigious Nikko!", to Kamakura and Enoshima, among other places, whose scenery and temples fascinate him. He visits places of worship, Shinto and Buddhist temples and mixes with the people, curious at "the strange customs of Japan": the new, the unexpected, although in the simplest intimacies of Japanese life, I am attracted and bewitched; and therefore you will understand my long, tiring travels, all over the place, not even I know where, blending in with the wave of people, following them to the most obscure, most absurd places.

He travels by train from Yokohama to Osaka: a long train journey, over miles of track, which I took several times between Yokohama and Osaka, is something of extreme interest, for the rapid glimpse of the passing landscape, and the forced intimacy with the good sons of the sun. He is concerned also with observing his fellow passengers: I used to buy my ticket, settle myself on the train, carefully choosing my observation post... I then took a curious look at the neighbours in the carriage, relating his impressions of the Japanese, their habits and customs. He also glances at the landscape, describes the rice paddies, villages, people and the little houses made out of wood and paper.

Arriving in Osaka, he is out and about day and night, part of the crowd, observing urban life, its trade with its "self-important little shops", the trades, festivities, the throng of people in the streets, and the winding alleys and canals of the city:

I think I have never used my legs so much before to the service of my curiosity; with a map in my pocket, consulted frequently, getting to know the labyrinth of narrow streets...; I visited temples and chayas, I wandered through the fields, and I confess, I came to imagine that the unconcerned Bohemia of my existence would never end, living solely through my eyes, in a continuous rapture of objects.

From Osaka he goes to Kyoto: temples, temples, and more temples; and the bonzes that scurry around and the flow of pilgrims... and when hours have passed, and you droop with fatigue, the coolie adds (your all-in-one guide, cicerone, the indefatigable narrator of national legend), that there are still another twenty or thirty temples to see, and to miss them would be to discredit you as a tourist.

In Nara, the visitor is moved in visiting the Daibutsu: He fills the whole space with his gigantic shape and with his, soul; seated on the symbolic lotus flower, with his right hand raised and open, the left resting on his knee, in the ample folds of his mantle, imposingly natural, the verdigris deposited over the centuries has left him with the soft appearance of velvet. The majesty of his gesture, which almost blesses, and even more the expression of sublime insouciance, sublime peace, that irradiates all around, emanates the strength that moves me.

And finally the farewell: already it is farewell to Japan, the last Sayonara... 'Sayonara'. Did you know that this is the sweetest word in the Japanese language, and the one to which the ear of the foreigner adapts immediately? Sayonara, adeus, au revoir; it is far more than just that. You cannot imagine the charm of the musumé when she rises on the straw mat, in a flurry of chasteness, humility, with simulated nostalgia, and whispers the sacred word. The first sayonara you receive enraptures you. The last, when you bid Japan farewell, quite likely never to return, saddens you, invades your whole being with the tremor of great inner emotions. It is truly difficult to bid Japan farewell.

He returns to Japan, however, on short trips at the service of the government of Macau. And he returns for good in 1899, when he is appointed Portuguese Consul in Hyogo and Osaka.

THE SECOND PERIOD: OS SERÕES NO JAPÃO13

[I]n love with this country, which is suggestively bewitching -how can you not be swept away by it! - my mind escaped me in the rapture of relating its enchantment.

The second period is the 'space in time' of life in Japan when Venceslau had the official responsibility of being Consul of Portugal in Hyogo, and later in Osaka and Kobe (1899-1913). It was in 1898, when the position of Harbour Master of the port of Macau was filled by an official less qualified than himself, that he asked the Portuguese government to appoint him Consul in Japan. In Kobe he tried to live in a truly Japanese environment, and in this way managed to penetrate Japanese life, changing his whole existence and maintaining only the official side of his life imposed by his responsibilities as Portuguese Consul. It was during this period that he met O-Yoné, a geisha from Osaka whom he married in 1900, in a Shinto ceremony. He says little or almost nothing about O-Yoné, apart from a few vague references and he talks of her as his cook or servant: my cook, O-Yoné-san (Senhora Bago de Arroz), knows that I like chestnuts and also knows that I like to listen to stories: two innocent pastimes. Yesterday at dinner, when she served ma a plate of chestnuts, she told me the following story.... Only later, after retiring from his official life and going to live in Tokushima, does Venceslau refer frequently to O-Yoné, particularly in his book O-Yoné e Ko-Haru, telling us of a visit to the tomb of Atsumori in the company of O-Yoné, a little before her death:

The penultimate visit I made to that place left me, as never before, with lasting impressions. It was the last outing I took with poor O-Yoné. It was the twentieth of June 1912, a beautiful day, and quite magnificent. I convinced her to accompany me and to see the tomb of Atsumori with her own eyes, as like all Japanese, she knew his story only too well. Off we went. O-Yoné, who usually stayed at home, feeling somewhat unwell, without knowing the cause, was livened by the event, and happy to feel the tepid breezes, and looked longingly at the exuberance of the landscape. For many months her face had shown the marks of some sign of morbidity, but she smiled sweetly. I served as guide... we gazed respectfully on the tomb of Atsumori. It was this intimate, spontaneous respect that inspires all sepulchres, no matter what the religious belief... Before taking our farewell of the place, we visited a small shop nearby, where a friendly creature offered pilgrims some special refreshment, in honour of Atsumori, mixed with other curiosities of the place. O-Yoné tasted these refreshments and bought some delicious peaches, eating one immediately, and offering me another, taking the rest home; laughing, happy with her outing...

Exactly two months later, that is on the 20th of August, poor O-Yoné died.

It is not easy to follow his life during this period because, due to his official position as Portuguese Consul, his writings are more impersonal. He does not talk of himself or his life apart from some occasional, brief descriptions, his home, outings or visits to some chaya. He does, however, talk to us of Japan, his feelings, his awareness of all that surrounds him, the beautiful landscapes, the sacred places, the rites, the festivities, the people and their culture.

This is no longer the occasional traveler who describes the impressions of his travels; but we still have the foreigner engrossed in the people and the country. His writings still bear the characteristics of his travel journals, short trips and outings to different places (always in Japan) and brief narratives on different aspects of life and culture of the Japanese people. He now gives us a different interpretation, another look at Japan and its people. He shows a concern for specifying details, in going more deeply into topics, despite retaining the same chronicle style, aiming these tales at readers in his own country. It is this need to look more deeply into the topics. born of his curiosity and love. nurtured by the object selected. transmitting Venceslau himself in his Serões.

Whoever has spent a few years in Japan and who has gazed with amazement, interest and love on this gentlest of exotic scenes, naturally experiences the desire to delve more deeply and look for greater detail. In view of such a task, the deeper one delves into the subject chosen, the more it seems impossible to understand it, to understand Japan and its people, to finally penetrate the dense mystery that surrounds it. However, every now and again, a fleeting glimpse of things flashes through the mind, sufficiently intense, however, to delight with a surprise. In this way the researcher develops a passion for his subject, becomes enthusiastic with the small discoveries he makes. He then thinks, in a sweet flash of altruism, that he can transmit his passion, his enthusiasm to others, to distant fellow countrymen... which, he rarely will achieve. From this is conceived the idea to write, to communicate in writing the feelings experienced: this quickly leads to the monograph, come to light in a newspaper article or book, which, in most cases, will bore the unforewarned reader to tears.

His literary production while he lived in Japan is defined by the narrative nature of his writing, including mainly reports, impressions, feelings, descriptions of customs, facts and events. The articles written between 1902 and 1913 for the newspaper O Comércio do Porto -"Cartas do Japão" and "A Vida Japonesa"- and "Os Serões no Japão" short chronicles contributed between 1906 and 1909 to the Lisbon magazine Os Serões and which later (in 1926) were published together in a book, date from this period. Venceslau himself confirms that they are simple loose notes, gathered together at random, with the only purpose of arousing some interest without being too tiresome -as they are brief- for readers in my country. Also dating from this period are "Paisagens da China e do Japão" (Landscapes of China and Japan, brief texts on Japanese life, customs and Japanese legends), written in around 1900 and published in 1906, and O Culto do Chá, published in 1905, in Kobe in which he describes the importance of tea in Japanese life. Some years later, in talking of O Culto do Chá, he tells of a trip to Uji, the land of tea: a small provincial city where some years ago I was inspired to write a small book about tea... I am deeply attached to the little book for private reasons. As for Uji, I never returned there after the book was published. Gratitude, if for no other reason, behooves me to return. Therefore I recently made this trip, at a pleasant time of year -in May- when the precious leaves of tea are being harvested; and can you imagine the excitement, the love with which I gazed again on these familiar landscapes and faces, aspects of the work which I observed closely, everything in fact to which I owe the fairly fortunate production of my literary whim.

Cover of Cartas Japão. Lisbin.

Sociedade Editora Arthur Brandão & Ca., n. d..

Cover of Cartas Japão. Lisbin.

Sociedade Editora Arthur Brandão & Ca., n. d..

Despite his official position, Venceslau is not deprived of his travels, his short trips, and particularly his mingling with the people, to go with the chusma to festivities, temples, "to the most picturesque of places", on a pilgrimage to see the fields of kiku (chrysanthemums) growing, to see the almond blossom, the sakuras (cherry trees), the azaleas: it is a pleasure for people to leave the town and travel out to the fields where the kiku grow, in their thousands, blooming in a multi-coloured show...; there were visits to the Nunobiki waterfalls, near Kobe, where in "short rests, the chayas, rest for a few moments, sip a cup of tea, and peacefully contemplate the scene, and where authentic musumés, of flesh and blood, elegant and smiling, welcome you with curtseys and gentle words in many tongues -'good morning', 'bonjour'- bringing you a cup of tea or glass of beer, cakes, and fruit. Beyond is the stand for photographs and illustrated postcards, tempting to the eye and your pocket book. There are festivities, the crowds passing by, the coloured clothing of the musumés, and the happiness of the people with whom he wishes to mingle, which he describes, enchanted, as glimpsing people, at night, the dazzling scene, illuminated by thousands of lanterns, animated by the dense crowd, seated on benches, laughing, singing, playing music, drinking, taking light refreshment.

From his frequent visits to Buddhist and Shinto temples, in Os Serões no Japão he gives us interesting descriptions of these religious places, comparing Japanese temples with Western temples: in the design of the Western temple the vertical line prevails, starting from the ground and rising to the heavens, the graphic symbol of the believers' faith; in the Japanese temple the preference is for the horizontal line, bearing witness to love for the earth, creation, the conscience satisfied with fate... the gods claim a garden; the architect is above all concerned first with the choice of a tranquil location, the enveloping grace of nearby trees, a neighbouring stream, the surrounding vista. But Venceslau not only observes religious places and their architecture, but also the believers, the pilgrims: I confess, it is worth observing the throng of faithful; mingling with the people, he enters the temples, attends religious ceremonies where they pray in chorus, chanting, with a hypnotic rhythm, which impresses, moves... recalling the sound of a voice, the sound of the waves, in their constant flow as they break on the sands, along golden beaches; accompanying the crowd, I enter a temple here and there with a pious gaze (add this sin to the many others I bear)... where the Shinto divinities are worshipped.

Venceslau de Morais, like Lafcadio Hearn, criticises the Westernisation of Japan, supporting Japanese nationalistic ideas and countering the effects of opening Japan up to the Western world: a host of foreign habits and customs has entered and is entering Japan, which is quite horrifying!... The trend towards change has been manifest for some time; but now it has become a positive fever, frenzy, delirium.

He fears the introduction of a stream of Western civilisation within the Empire, with its string of vices, and disbeliefs because this is, without a doubt, a terrible factor in disintegration; but he has faith in the Japanese people who, although outwardly seem susceptible to all new suggestions, the Japanese soul, gifted with so many fine attributes, such high standing values, will remain unchanged and untouchable, and above all he trusts in the social and religious institutions; while there are still Shinto temples in Japan and believers attending them, I feel that this country will be a privileged nation, united by strong bonds of sentimentality and protected from the major social dangers spreading across Europe and America. He frequently emphasises the successes, attributes and qualities of Japanese society -or what he considers as such- but he omits its problems and its social tensions. He is a conservative and somewhat impartial observer. Japan fascinates him because of its traditions, ancestral customs and not only because of the beauty of its landscape or the Japanese woman. He looks in rapture, describes what he sees and feels, but he omits or tries to reduce the social problems of Japanese society. The effect of progress, the opening up of Japan, which slowly disappeared with westernisation, appeared to him as a major risk that might upset the values of Japanese society, although he is convinced that this extraordinary people, that has given the world renowned examples of its wisdom and which in the space of little over thirty years was able to rise from its mysterious isolation to become a modern civilisation... clearly understands its situation and the correct route to follow towards its gradual growth as a nation.

His fascination with "the daughter of Nippon", the musumé he describes, exalting her physical beauty: her hands -dainty hands, and her feet- dainty feet; her charm: the charm that resides in her, is not derived from sexual characteristics; it is rather more a colourful charm of lines, murmuring undulations of silk and satin; or even the charm of a flower, the charm of an insect, or that of a bird with multicoloured plumage. It is not only the charm of the musumé that he describes; now his gaze stretches further and tries to apprehend the feminine condition, in the family and Japanese society. For Venceslau de Morais -a conservative, for whom the new social ideas of the West are a sad degeneration of Western society- the role of the woman, her true kingdom, where she displays her finest features, is within the family, because her place in the social field is minute; the man is the head of the family, he is the leader, he is the king; the woman obeys him.

Musumés, the supreme enchantment of Japan!... I myself confess that I was brought here by the tiny white hand of a musumé, who led me by the wrist and never abandoned me... It is she who guides me by the path of this country of seductions, pointing out the cherry blossom, the woods of green pine, the temples on feast days, legendary places, the little paper houses, this happy people. Where else will she lead me?... I do not know; randomly, to conclude the excursion that has already been long, to some tiny village cemetery, all in exquisite serenity, full of mossy stones with half faded inscriptions, full of red azaleas, butterflies in flight to the chirping of crickets; inviting me then to rest there, on the pillow of soft earth, which I take to be my right.

THIRD PERIOD: FROM KETO-JIN TO MORAIS-SAN O CULTO DA SAUDADE14

Japan was the country in which I most lived by the spirit, where my thinking individuality most saw the horizons of reasoning and understanding extend, where my emotive strength breathed most in the presence of the delights of nature and art. Japan was then the altar of this my new cult -the religion of nostalgia- certainly the last that I shall love and revere.

The third period or 'space in time of his life in Tokushima lasts from 1913 to 1929. In 1913, Venceslau asked to be relieved of his duties as Portuguese Consul in Kobe and went to live in Tokushima. 15 The incompatibility of his official position with his private life worried him. He began cutting off his ties with Portugal, breaking away from disillusion, the injustice of the Portuguese government and the death of O-Yoné in 1912, led him to take this decision. He decided to give up the official life and finally live a Japanese life style in the country: Happy is the man who, in his declining years, and already at the end of the journey, having provided his round of activities, as best he knew how or as best he could, to his country, finds in himself the possibility, pretexts and courage to renounce all his duties and all his rights, withdrawing into isolation, poor, forgotten, shrouded in the just indifference of his fellow countrymen. I found this possibility and these pretexts and I had the courage and, therefore, not greatly blessed by the kind hand of fortune during my lifetime, I now feel satisfied with destiny, and content with the moral suicide that I have committed. The idea of returning to Portugal to enjoy his retirement was abandoned after the death of O-Yoné. He followed Japanese tradition and withdrew to Tokushima, O-Yoné's native land.

My reason for preferring Tokushima for my retirement is easy to explain. A short time ago -less than two years-, on a certain afternoon in August, someone taking my hands within hers, made me a fleeting request. Poor creature, with a large family -mother, brothers and sisters- all, however, absent and, quite frankly, scarcely interested in her well being. She knew only too well that I was the only person who, from the heart, could try and satisfy her desires, no matter how complicated they were. She asked me to protect her life...

And I did not satisfy her request; it was not in my power to do so. She whispered some words of resignation, clasped my hands in a last effort (do I still feel this hand clasp?...) and let herself die...

On the day following her passing away, her body was cremated in the Kobe crematorium... and the ashes taken to Tokushima, the native land of the poor departed creature, and placed there under a stone in a single grave in one of the several cemeteries of the town.

After some months, I found myself one day in Kobe completely independent, completely alone, with no responsibilities, no duties, and because of this forced to take an immediate decision.

I then murmured to myself: count the coppers you have in your purse and then measure the limits you can place on your whims. You are free, forge on... Flee the living, go to Tokushima, close to that tomb which recalls a dear name, which brings you nostalgia.

Man, with regard to his sentimental life -the only one that can still open up horizons- can only live in two ways, in hope and in nostalgia; when the end of the voyage of existence is drawing near, all hope is dissipated, and it is logical to seek consolation in nostalgia.

And so I came to Tokushima.

However, despite the death of O-Yoné having had a considerable influence on this decision, particularly in the choice of location, it is a mistake to imagine, as we have thought and written, that Venceslau then spent his time dwelling only on the morbid recollections of the diseased. In Japan, as in China, the dead live; only the transitory body perishes, but the soul, the strength of personality, which gives and receives affection, continues to exist in the home, mingling with the reading of books, intervening, watching, protecting.... It is common in Japan for the widower or widow to sell everything to go and live close to the ashes of the spouse. Venceslau did no more than follow the Japanese custom. 16

His decision to retire from official life can be seen as a liberation: I think now to steep myself in unspoken suggestions of independence, freedom, peace, faced by simple country scenes, far from the confines of a sophisticated life, false appearances, as life is in large civilised areas, for which my contrite soul has for some time now been decidedly incompatible.

Now he is free to dedicate all his time to his occupations as a writer... free to launch himself into this genuine source of Japanese life, to drink from the lustrous, virgin waters. Now he can speak about himself without reservation17

[I]mprovising, in the last quarter of my life, in this isolation of Tokushima, my mind is faced by full freedom of action. I can do as I please, and think as I please. This is the moment in Venceslau's life when his writings are most personal (with the exception of his set of "Relances" (Glimpses): Relance da História do Japão (1924) and Relance da Alma Japonesa (1925)), his work during this period is like an intimate diary, in which he talks about himself, his life and the daily routine in Tokushima. He writes Bon Odori em Tokushima (1914-15) with its subtitle "a notebook of intimate impressions". This is a literary style characteristic of Japan, nikki or a notebook of intimate impressions, which Venceslau adopts to describe his impressions of people and life in Tokushima, and also himself, his home and his daily routine. It is, as he himself states, in beginning to date his impressions that he decides to give them the style of a diary, similar to the literary style of impressions, separate notes, which clearly deal with the time even the season of the year, in which they were written. Then he wrote Ko-Haru (1916), first published as a booklet and later in serial form in the newspaper O Comércio do Porto. Ko-Haru was later included in his book O-Yoné e Ko-Haru (published in 1923). This is a more personal book. He is no longer the observer who "observes from outside", but he now describes his deepest impressions, feelings and memories, his daily life in the city of Tokushima. Now he is the principal protagonist.

In retiring to Tokushima, "a great city with village customs", on the island of Shikoku, he renounces everything. Not quite everything: In exchanging my residence (home and office) in Kobe for this simple retreat in Tokushima, I wisely discarded the kaleidoscopic mountain of things that I had accumulated in almost sixty years of my life. But a tiny portion remained to me, tiny in size, but of great value, which, at all costs, I would not, and could not divest myself of: and it is this tiny remainder which I gaze upon and which fills, against all the rules of fine Japanese taste, my exiled retreat.... But am I by chance Japanese? No, certainly not. You do not cast off a race, you do not cast off a country. And there is nothing here that smells of sentimentality. You do not, and cannot, cast off ancestral inheritance, tendencies, preferences, the legacy of innumerable centuries, passed down through an infinity of predecessors, although the whims of destiny carry us to the far corners of the globe. Here, then, isolated completely from the civilisation of the whites, I will not seek to be one of them, I will not cease to be white, to be Portuguese. in colour and sentiment, denouncing my individuality down to the smallest peculiarities. Scrupulously. he chooses both his books (among them Camões. Fernão Mendes Pinto and Lafcadio Hearn), and his memories: trivia, futilities, reducing everything to memories... My mortified mentality can be compared to a great octopus bearing enormous tentacles, which extend in all directions in an anxiety to apprehend, to embrace everything that talks to him of the distant past. And it is there, in that provincial city, that he spends the remaining years of his life. It is in this land of gods and Buddhas, in Tokushima. where I came to establish my shelter, where I came to seek peace and tranquillity, for body and mind. What daring! What incredible daring, for a fair skinned man, a man from the countries of the white race and, above all, a Portuguese!. There he lived with Ko-Haru and was converted to Buddhism. Martins Janeira is of the opinion that conversion to Buddhism was a question of adopting Buddhist precepts as a way of penetrating more deeply into the Japanese soul and of this proof is given in his last books, which become ever deeper as he becomes involved in Buddhist ideas, whether expressed in classical literature or in acts as they are manifest in the life of the Japanese family. 18On the other hand, might this conversion to Buddhism not also have been an attempt to be more easily accepted by the Japanese family?

About Ko-Haru he writes: I knew Ko-Haru well, I was chatting to her a few days ago... Ko-Haru was a slender, dusky, happy, lively girl who seemed to advertise health. She could not be called a beauty, she was far from that. She had charm, however, in her tall slender form, in her easy going gestures like those of a child in the street and it was usually in the street that she thrived, in her gentle open stare, her smile in which her mouth at any moment curved, revealing two rows of sparkling white teeth. the perfect shape of her hands and feet. Above all she was intelligent, more so than the vast majority of women of her humble social level; with a fine artistic temperament, inquisitive, interested, easily impressed with the beauties of nature; and with a soupçon of dream-like poetry fermenting within, in the innermost corner of that bright brain. Ko-Haru died of tuberculosis at the age of twenty three. Venceslau stayed with the sick girl from the day she entered a hospital in Tokushima, until her death:

On the afternoon of the first day of Bon-odori (dance of the festival of the dead) in Tokushima, that is, on 12th August 1916, Ko-Haru was carried on a stretcher, at her own special request, from her home to a hospital in Tokushima... Ko-Haru was usually alone, having only her suffering for company. I spent a few hours with her daily. Relations and acquaintances were rare. Her own father, mother and sisters showed little care... [a fact] that intensely revolted my sympathetic nature as a European, although, after giving thought to this, it seemed natural and in harmony with the universal laws of creation. At the start, I thought that parents would sacrifice everything and everyone -self interest and attention to healthy children- to give help to a sick child, who was suffering. I was entirely misled... Ko-Haru became the weakling, who had to be abandoned, to the benefit of the healthy, expectant offspring. I alone remained to care for her.

The monk Yue Washino, at Tokai Temple in Tokushima.

He knew Morais and now officiates in his worship.

After Ko-Haru's death on 2nd October 1916, he was completely alone, living on memories and nostalgia: it is always nostalgia, always nostalgia that comes to worry us!, living on memories of the past, living on the memories of the two women he had loved:

It was, as I said, on one of the these last nights in June, around nine o'clock, a dark humid night, dripping moisture, irritatingly warm and oppressive.

I had left home, and visited two familiar tombs in the same cemetery, done some shopping and returned home again, tired, irritated, ill at ease to which certainly the inclement weather contributed...

Having visited the busy streets of Tokushima, I returned to my quiet neighbourhood, almost a village, which surrounded my small home. A little later, I arrived at my own street, which is absolutely secluded, plunged in shadow and silence... Now I reach my door. I reach into my pockets for the key to the protective lock, which protects me from possible visits by thieves. I find the key but, blinded by the shadows. ill at ease because of the disconsolation I feel, by the weight of my parcels, the fatigue that irritates me, the drizzle wetting me, I make struggled attempts and endless maneuvers without getting the key into the lock to open the door... Then, from the thick branch of the only tree, an oak, that stands solid and watchful at the entrance to the house, the bluish light of a glow worm glimmered and began to flicker around me, so close to my hands and the key, that it allowed me to easily fit my key into the lock and to enter my house.

Blessed insect, that appeared like that, in the wide curve of a casual flight, to so gently help me! Casual? And why not premeditated?... I begin a train of strange conjecture. In this great city of Tokushima, which has around 70,000 inhabitants, two single creatures, no-one else, two local women, daughters of the people, of the same family, aunt and niece, O-Yoné and Ko-Haru, would, if they still existed be able to carry out the difficult task of coming from afar, dragging their sandals through the mud, a transparent paper lantern held in their fingers, to light my way and help me open my door. But these two creatures can no longer come here, and will never come here again; they no longer exist, they both died... no, they can no longer come here, they will never come here again... but that insect, do the Japanese not believe that their dead can return to earth, incarnated in other bodies, a bird for example, an insect for example, although retaining the effective memory of their previous existence...

After this last interrogation, about which my mind wandered, I felt anguish weigh so heavily on me, that my heart suddenly began to palpitate. It lasted but a moment. Then, more serene, I could not contain these words: Was it O-Yoné?... Was it Ko-Haru?...

And in another passage he describes his daily reading and his dinner on a feast day alone, or rather, in the company of his cat and with the memories of his loved ones, his sister, O-Yoné and Ko-Haru:

It was the first day of January of 1919... A feast day. I was at home alone, which is often the case; alone, with my cat, with my chickens and with other animals of lesser importance... Fine, a feast day. I had already swept the house, already fed the animals and already taken care of other humble tasks. Now, I must break coal, light the fire and prepare my dinner -dinner for a festival, apparently- Well then, hands to work...

When I tasted my dinner, my knees on the mat, alone with my cat, I noticed that the cat showed a considerable fondness for the sardines, but turned up his nose at the cabbage soup: a question of education. Alone, said I but to be more truthful, I should rather record that accompanying me, as they always accompany me, but on that feast day even more so, were the memories of my absent sister and the memories of my dead. At a certain point I caught myself smiling, in this way responding to certain smiles that I imagine came from afar and were directed at me: smiles, slightly mocking, from my sister, as I was eating the sardines; smiles slightly mocking from my departed O-Yoné and Ko-Haru, as I savoured the cabbage soup...

On the twentieth day of every month, the anniversary of O-Yoné, he received a visit in his home from the Buddhist bonze, an ama-san, who comes to pray at the butsudan, the altar for the dead; prayers for some poor little entities, whose spirits it is thought people to a certain extent the small house where I live; prayers of a religious cult, which is not my religion, mine is another, -and what would my religion do here? - but which was their religion, the religion of the poor departed little entities, the religion that wrapped them in beliefs throughout their entire life.

He lives alone, Ah, solitude! A vast dry parched field peopled by ghosts in a land which does not understand him and which calls him Ketô-jin (bearded savage): here, in Tokushima, on my lonely walks, sometimes the local urchins and simple people shout an insult as I pass by "tôjin!" or "ketô jin". This has happened to me before in other parts of Japan, but less frequently. But these six year olds who smile at me would certainly not want or know how to offend me.

Despite his solitude, his disillusions, and incomprehension of the native people, there is not a word in any of his works which is offensive or hostile to the Japanese people and his love of Japan continues. But in talking of Lafcadio Hearn would he not also be talking of himself when he says that: in prolonged contact with exoticism, the European man recognises, generally too late and in disappointment, that a major moral barrier separates him from the people with whom he wishes to live, whom he wants to love and by whom he wants to be loved? Like Hearn, Venceslau was a man of passion, with a sensitive, delicate temperament. But where Lafcadio Hearn finally showed a certain bitterness towards the country and people that had captivated him, Venceslau shows no feelings of hostility nor any lessening of his esteem and love for the Japanese people, despite his obvious disappointment and misgivings about never having been accepted by Japan: and so insinuating was the impression that enveloped me in an environment of benevolence and blessing, leading me to smile at people I met in the street, also gaining a smile in exchange, which I would interpret, grateful, as a warm greeting... only later did I recognise that I was illuding myself and that the smiles of this good people of Tokushima, distrustful, conservative, cordially detesting the European, simply expressed scorn and aversion for the white man.

A year after settling in Tokushima he states that he does not regret the step he has taken: during the first year of exile and recognition, no serious incident occurred to bring down the edifice of my insipidity. Practically the whole time has been spent in the silent work of adaptation, required for the environment and special conditions of my new surroundings... but suffering always, finding only some pleasure in feeling myself closer to natural scenes and in, perhaps, better understanding them. However, I do not regret my moral suicide, rather I am increasingly convinced I am in the only environment which is in some way compatible with the state of my soul and with the conditions of the desolate existence into which I have fatally fallen.

In O-Yoné e Ko-Haru, more particularly in the chapter headed "The Barrel of Litter at the Chiyo on-Ji cemetery", Venceslau de Morais with the objective of giving a few friends a brief outline of my insignificant personality, paints a selfportrait, in his solitude, desires and fears, particularly this fear of not being accepted, not even after his death, in the Japanese family:

[T]he individual that I had before my eyes, with an air of abandoning himself, others and everything else, gave every undeniable sign of one of these poor devils, of one of these pariahs whom the West throws every now and again to exotic, distant lands, because they are wanted nowhere and by noone; some Joe Nobody, a shipwreck of life, who has probably done a thousand tasks and suffered a thousand set-backs in a life of adventure: now asking destiny for no more than a little peace and a glimmer of soothing sun, on the foreign soil on which he finds himself.

The man wore a modest suit of blue flannel, ill-fitting to the body, ragged and dusty, with a plentiful covering of cat's hairs stuck to the surface of the material, revealing that the careful hands of a woman no longer shook his clothes or kept them in order. He wore a grey cap on his head. His wrinkled hand supported by a rough walking stick. His hair, long and curly, fell down his back. A long unkempt beard framed his face, occasionally stirring in the breeze. His hair was still fair; the beard was almost completely white, but that white that has something of straw colour, that never achieves complete whiteness in those beards that were in younger days fair...

Passing the street urchins, at that hour plentiful, some shouted at him "ketô-jin!" (bearded savage!), others, playful, made him a military salute, sticking their tongues out at the same time. Even the little girls made the same mocking gesture; but... so gentle is the grace of their sex in Japan, that the same scorn becomes playful and more like a caress. The old man smiled faintly at all of that, with what intention it is hard to say, either in gratitude or irritated: but, suddenly, I noticed that he stretched out his hand to touch the head of a little girl close to him, lightly stroking her pitch black hair....

The old man, no doubt familiar with the place, left the Tenjin temple on his left and resolutely made for a dark lane... A few steps on, we find him in a vast cemetery. By this time he had realised that I was following him. He stopped, waited until I drew near and spoke to me in Portuguese in more or less the following words:

"I note that your curiosity leads you to follow me and to wonder what brings me here. I will satisfy your curiosity immediately. First of all: do you know the name of this cemetery, that has a small adjoining temple? This is the Chiyo on-Ji cemetery... Let us move on a little. I want to show you two tombs of two women that I knew well. There they are. To the right the tomb of O-Yoné, who has been dead for seven years: and here, nearby, is the tomb of Ko-Haru, her niece, who has been dead for close to three years. I had both of these tombs built; I owe this pious commemoration to the memory of the two of them. It is these two wretched friends that I come here to visit frequently. Note that when a person has no living friends, they find in their dead friends a gentle consolation to their suffering... and now, let me add that it is in this same cemetery of Chiyo on-Ji that I desire a sepulchre to be built one day for my ashes, after cremation, as is the custom here; not isolated but accompanied by other ashes; it is odd to confess it -he laughed at the childishness- but although used to solitude for many years, the solitude of the tomb fills me with horror. When I came to Tokushima, of the two tombs I showed you, only O-Yoné's tomb was built. The idea then occurred to me that my ashes would find a good shelter close to hers, beneath the same urn; but such a favour was quickly denied me by her near relatives, her mother and brother, who broke into a vociferous religious fury, as if it were a sacrilege, an ignoble pollution... which is the most striking example of racial intolerance that Japan, in my long years of experience, has shown me. Some time later, Ko-Haru died, and this sepulchre that you see here was built for her. And so I asked her mother: "And do you also deny that my ashes rest in the tomb of Ko-Haru?" "No, I do not deny that", she promised me. Well, this business has been shelved, to be dealt with at the proper time; but I confess that such a promise inspired little faith in me. Shortly afterwards, Ko-Haru's father died. And soon after that Ko-Haru's son died (death shows a predilection for those poor people). And zap! zap! Ko-Haru's tomb was opened twice to receive those two additions of ashes; not that her mother told me, perhaps out of correct courtesy, but I myself noticed what had happened, as I saw fresh signs of rites performed for the last two deaths on the tomb. And I began to think: Now, Ko-Haru's mother, affected by the poverty in which she lives, the indolence and apathy she professes for all events in life, is perhaps a kind of impartial thinker, free of preconceived ideas, superstition and everything else. For her the tomb of her daughter is like a barrel of litter at the Chiyo on-Ji cemetery, where she thinks it is her right to empty all the leftover waste, that is, the ashes of all her dead... One more handful of ashes -mine- would not cause an enormous disturbance, in the circumstances I have described; particularly if the favour were given gracious retribution with a few silver coins from my spoils. However, I begin to believe in the sincerity of the promise made and to convince myself that perhaps, Ko-Haru's tomb will again open one day to receive my remains".

The old man made me a gesture of one who has nothing more to say. I understood. I extended my hand in farewell, gave him my name and asked him his. Without hesitation he replied: Venceslau de Morais.

He died on the 1st of July 1929, in his home at Tokushima. In his will, dated 12 August 1919, he asks to be cremated and buried according to Buddhist rites, showing his concern and fear of not being admitted -a ketô-jin- in a Japanese cemetery, a sacred place reserved for the sons of Japan. He was not refused this last wish. He was cremated and his ashes deposited in the Chiyo on-Ji cemetery beside those of Ko-Haru.

Nowadays in Tokushima the people respect him, and respectfully refer to him as Morais-San.

ONE LAST GLANCE

We know that, despite all, our travels, reading and meeting other people like us, are means of enhancement that cannot be denied.

Marguerite Yourcenar

From subject-traveler to subject-wanderer, from ketô-jin to Morais-San or Porutugaru-San: Venceslau de Morais, who made Dai-Nippon the desired, inner object of his work, is an impassioned narrator who inspires passion, whose work is the pleasure of speaking, narrating, communicating, his view, his impressions and his feelings. Refusing methodical, realistic or scientific (or rather pseudo-scientific) discourse, he prefers the intimate narrative, "glimpsing" impressions, "talking" at random: I write intimate impressions, in a wandering pilgrimage of the thoughts, a pilgrimage which I particularly like but which no doubt is almost sterile to those who have the patience to accompany me. Methodical explanation offsets subjective perception, from the pleasure of writing to the delight of inspiration, and his vast works are almost a single text, as he himself wanted and for which he had already imagined a title: Album de Exotismos Japoneses, a work in which the same topics are constantly repeated, but the desired object -Japan- always remains the same, although developing, and dynamic: the vitality of Morais' works comes from his increasingly deeper penetration into the Japanese soul and in apprehending and defining the cosmorama of its innumerable facets. 19

Venceslau de Morais' life in Japan is an on-going developing itinerary, and his work reflects this continuity in time and space, and the interruptions made to it. In the early years of contact with Japan, Venceslau gives us a view of exotic Japan, in a description written by the traveler fascinated, moved by a passion for the exotic, the picturesque and the marvels of land and people; no doubt it is a superficial view, but rich and fascinating. His view of the Japanese world deepens as he lives more closely with the people; and finally it becomes more profound, richer and above all more personal in the last years of his life, as a result of his long, desired life with the Japanese people.

As was said at the beginning of this article, the aim is not to give a chronological report on the life of Morais in Japan, but to observe his life and his view of the Japanese world through his writings. Here only an attempt is made to suggest an interpretation of the life of Venceslau in Dai-Nippon, supported by his works. A more detailed examination of his view of Japan will be the object of a different article, "The view of the Japanese World in Venceslau de Morais" from which information was taken to write this first, brief introduction.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

This article is part of a larger work, "A Visão do mundo japonês em Venceslau de Morais" (The view of the Japanese world in Venceslau de Morais), in which it is suggested that the view of the Japanese world described by the subject-narrator should be observed through his writings. In this article we have merely attempted to suggest an interpretation of the life of Venceslau de Morais in Japan, an interpretation based on his writings published in books, establishing a relationship between his works and the author's life in Japan.

NOTES

1 Armando Martins Janeira, in the introduction to Os Serões no Japão, 2nd. edition, Parceria A. M. Pereira, Lda., 1973.

2 Armando Martins Janeira, in the introduction to Os Serões no Japão.

3 Armando Martins Janeira, in Os Serões...

4 Celina Silva, in the introduction to Dai-Nippon, Livraria Civilização Editora, Oporto, 1983, page 23.

5 Terminology should be explained regarding the concept of história de vida: English has two precise words - 'story' and 'history'; by 'life story' we mean the 'story of a life' as the narrator lived it and described it; French adopts the expression récit de vie with the same meaning as it is used in 'life story'. By 'life history' is meant the history of a personal life, based not only on what the subject-narrator left, but which includes the use of a series of documents and sources other than the subject-narrator. Here the expression história de vida is used meaning 'life story' or 'récit de vie' that is, the 'história de vida' as it is related to us by the subject-narrator.

6 On biographical method consult Daniel Bertaux, "L'approche biographique. Sa validité méthodologique, ses potentialités", Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie, special number. "Histoires de Vie et Vie Sociale", volume LXIX - 1980 and Franco Ferraroti, Histoire et Histoires de Vie. La méthode biographique dans les sciences sociales. Paris, Librairie des Méridiens, 1983.

7 The statements and writings of Venceslau de Morais which referred to the 'initial period' were selected from the book Traços do Extremo Oriente, the chapter "Saudades do Japão", Livraria Barateira, Lisbon, 2nd. edition, 1946.

8 Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, page 192.

9 Armando Martins Janeira, op. cit., page 192.

10 All biographical works (biographies, memoirs, life stories) are always subjective: biographical narration is a human act, in which the experience and interaction between the 'I' and the 'world' reveals a 'special I' and a 'personalised world', meaning that this human practice which is the biography, tales of life, or memoirs, is a synthetic activity, an active totalisation of the social context; or, in the words of Ferraroti, "loin d'être l'élément le plus simple du social - son atome irréductible - l'individu est également une synthèse complexe des éléments sociaux", and this human act of biographical narration comes from the individual as a social being, as a "complex synthesis of social elements", in a specific social context. This is the social context that Venceslau de Morais chose to live in, which he tried to convey in his writings, and at which we should look, although. Obviously, this universe is revealed to us through the formation of a particular subject in the form of a 'personalised world'.

11 Jorge Dias, "A perspectiva Portuguesa do Japão", Boletim do Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 2, Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, page 107.

12 Venceslau de Morais was born in Lisbon on May 30th, 1854. He chose the army as a career, but then left the army to join the navy; he completed his training as a naval officer at the Naval Academy in 1875 and went to Macau in this capacity in 1888 where he was appointed Harbour Master of Macau in 1891. He remained there until 1899. As a naval officer he travelled several times to Japan where he settled in 1899 when he was appointed Portuguese Consul in Hyogo and Osaka. For the life and work of Venceslau de Morais, consult the works of Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido ou a aventura maravilhosa de Venceslau de Morais no Japão, one of the most exhaustive and interesting biographies of Morais.

13 The writings which refer to the "second period" were selected from the following books: Os Serões no Japão, Parceria A. M. Pereira, Lda., 2nd. edition, 1973: A Vida Japonesa (1905 -1906), Livraria Chardron de Lello & Irmão, Oporto, 1985; Cartas do Japão, 2nd. series (1907-1908), Lisbon, Portugal-Brazil, Soc. Editora; Cartas do Japão, 1st. series (1902-1904), Lisbon, Parceria, 1977.

14 The writings that refer to the "third period" were selected from the following works: O Bon Odori em Tokushima, Oporto, Companhia Portuguesa Editora, 2nd. edition: O-Yoné e Ko-Haru, Oporto, edition published by A Renascença Portuguesa, 1923.

15 His request asking for immediate resignation as Consul and officer in the Portuguese navy dates from June 10th, 1913: in this request Venceslau de Morais invokes "most important personal reasons" in his private life and states that he wishes "to remain in Japan, where [I] expect to be engaged on a a task incompatible with any post in the Portuguese Civil Service, even in retirement, possibly even incompatible with retaining Portuguese nationality". Was Venceslau de Morais perhaps contemplating taking Japanese nationality, as Lafcadio Hearn had done?

16 Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, Oporto, Livraria Simão Lopes, page 87.

17 Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, Oporto, Livraria Simão Lopes, pp. 185-186.

18 Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, Oporto, Livraria Simão Lopes, page 151.

19 Armando Martins Janeira, O Jardim do Encanto Perdido, Oporto, Livraria Simão Lopes, page 103.

*Graduate in Sociology from the I. S. C. T. E.; student of the life and works of Venceslau de Morais. Currently researcher in the Programme for the Arts and Traditional Skills, Interministerial Programme, Lisbon.

start p. 173

end p.