The first Portuguese contacts with the Kingdom of Siam date from the beginning of the sixteenth century, more precisely the year 1511, contemporaneous with the siege of Malacca conducted by Governor Alfonso de Albuquerque. The latter knew that Siam was at that time the most important state in the region and moreover, that it was engaged in war with the Sultanate of Malacca which, once its vassal, had been in a state of revolt since the final quarter of the fifteenth century. In fact, in the light of this knowledge, Alfonso de Albuquerque decided to send an emissary to the city of Ayutthaya, the Siamese capital, in order to forge friendly relations between Portugal and Siam and win the support of that state with respect to Portuguese activities in Malacca.

This mission was conferred on Duarte Fernandes. Above and beyond political objectives, it also had, of course, a commercial goal, this being one of the chief motives behind Portuguese exploration of the East: Siam seemed at first sight to be a potentially fine future trading partner.

The embassy of Duarte Fernandes received a friendly welcome from the King of Siam, Ramathibodi II (1491-1597), who must have immediately realized that the Portuguese, well-equipped with firearms, constituted a new force to be reckoned with in the Asiatic world, with whom then, it was preferable to maintain healthy relations. Hence he resolved to send a Siamese embassy to Malacca in return for the Portuguese initiative.

Alfonso de Albuquerque took immediate advantage of Ramathibodi II's positive response by sending a new diplomatic mission to Ayutthaya at the beginning of 1512, on this occasion composed of seven Portuguese under the leadership of António Miranda de Azevedo.

The embassy of António Miranda de Azevedo also met with a good reception from the King of Siam, who accepted the Portuguese proposals for friendship and trade. 1

Once good Luso-Siamese rapport had been established, the way was open for the development of commercial relations. The King of Siam took the first initiative, sending a junk laden with rice to Malacca in 1513. The Captain of that city, Rui de Brito Patalim, immediately made the most of the opportunity and sent to Siam three junks armed by the governor and chief of Malacca. 2

However, the Portuguese authorities were quick to realize that trade with Ayutthaya was not as productive as the kingdom's sheer size had initially suggested. In fact, Siam was a predominantly agrarian state, and commercial activity was little developed and restricted by royal monopoly, mainly with respect to international trade. In addition to this, Siam was not a state that produced valuable merchandise, such as spices, which was what most interested the Portuguese Crown. Indeed, Siamese merchandise was limited to provisions (chiefly rice),balsam, lacquer, aloes-wood, sappan-wood, musk, tin, lead, some gold and silver, ivory, deer skins and silk fabrics, products of little importance for the inter-continental traffic in which the Royal Exchequer was involved.

Thus, once the Portuguese had consolidated their presence in Malacca, the Portuguese authorities quickly lost interest in commerce with Siam, allowing trade in that kingdom to be freely exploited by private merchants.

If the rich spice trade constituted the chief motive behind the Portuguese Crown's interest in the East, then the commerce of Asiatic merchandise similarly became the main objective of all the Portuguese voyaging to the East Indies. In truth, all these men quickly began to develop commercial interests, both in conjunction with the execution of royal duties or other functions, and exclusively dedicated to mercantile activities.

For those Portuguese whose interests were exclusively limited to the Asiatic zone, trade with Siam offered many attractions. Hence, the opening left by the Portuguese authorities would be rapidly capitalized on by the private merchants, especially after the substitution of Alfonso de Albuquerque by Lopo Soares de Albergaria in the government of India in 1515. As early as 1516, the private merchants began to converge on Siamese lands, where they were well-received by the respective monarchs, for whom their presence constituted a means of access to the advanced military technology of the Portuguese.

In spite of the lack of documentation, the Portuguese presence in Siam continued by all accounts to grow throughout the first half of the sixteenth century, related on the one hand to the traffic operating out of the coastal ports of western Siam, especially Tenasserim, Tavoy and Phuket (Iunçalão), and on the other hand the east coast, otherwise known as the Gulf of Siam.

On the Siamese east coast, comprising in particular the cities of Ayutthaya and Nakhom Si Thammarat (Lugor), the commercial activities of the Portuguese were closely linked to the China trade. The Chinese merchants had always frequented the Kingdom of Siam, where they would sell the coveted silks and porcelains of the Celestial Empire and obtain tin, ivory and sappan-wood. The merchandise brought by the Chinese was not, clearly, consumed in its totality by the Siamese, and there was always a certain amount left over which could be acquired by merchants proceeding from other regions. The Portuguese traders, also keen to obtain the valuable Chinese merchandise, soon realized that Siam occupied a privileged position in that trade. Thus, whether for the acquisition of Chinese merchandise in Siam or Siamese goods to be directly traded in China, the Portuguese merchants began to seek out the ports on the kingdom's east coast.

To take the narrative of Diogo do Couto at face value, the first Portuguese landing in Japan in 1554, led by António da Mota, Francisco Zeimoto and Antonio Peixoto, was the result of an abortive commercial voyage to China from the port of Siam (Ayutthaya), which came amiss in adverse weather conditions. This accidental voyage would prove most profitable since these three Portuguese men did good trade in Japan, making their way later to Malacca with news of their success. 3

Henceforth the Portuguese were aware of the rich trade to be had with Japan, whose principal merchandise was silver, a metal of great importance in commerce with China. This brought confirmation of a piece of news that was doubtless already circulating among the private traders, to the effect that Siamese goods, namely sappan-wood, ivory and deer skins, were in great demand in the Japanese empire. 4

As this news spread among Portuguese traders, it no doubt provoked the growth in trade with the eastern ports of the Siamese coast, as reflected by the presence of more than a hundred individuals in Ayutthaya at the end of the first half of the sixteenth century. 5

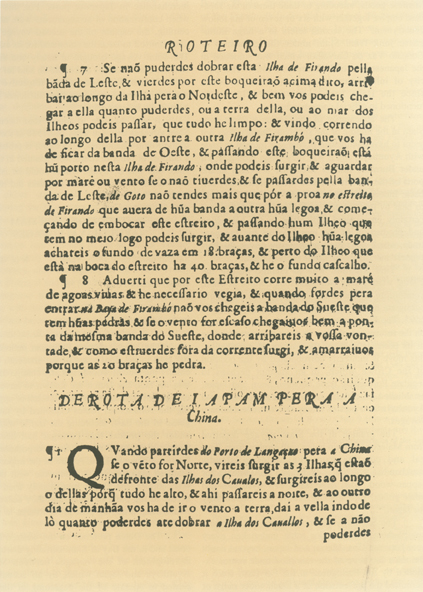

Sailing instructions for Japan, by Vicente Rodrigues & Pilots, the first to be printed in Portugal.

Sailing instructions for Japan, by Vicente Rodrigues & Pilots, the first to be printed in Portugal.

Concrete information about Portuguese trade between Japan and Siam is unfortunately somewhat scarce. In fact, it was possible to locate only two references to this trade. The first, related by Fernão Mendes Pinto, tells us that the author of Peregrinação was in Ayutthaya around 1547, after traveling from Sunda in the company of two Portuguese who continued on to Japan and who had lent him one hundred cruzados with which he purchased Siamese goods, intending to trade them in the Japanese empire together with six or seven of his fellow countrymen. 6 The second refers to a large Portuguese junk from Siam under the command of Gonçalo Vaz de Carvalho, which was stationed in the Japanese port of Yokoseura in 1563. 7 This paucity of information is comprehensible, however, since the issue here is private traffic, rarely mentioned in official correspondence.

The appearance of the Burmese threat over Siam in the middle of the sixteenth century does not seem to have diminished Portuguese interest in trade with Ayutthaya, and it was only when the latter fell under Burmese rule in 1569 that activities in the ports of the western Siamese coast suffered any setback. Indeed the destruction and expulsions brought to bear by the Burmese gave rise to instability, and certainly engendered difficulties in the harvesting and production of the merchandise for Japanese trade, which must have temporarily driven the Portuguese merchants out of the ports of Siam.

This situation was to change during the 1580s, when prince Naresuan took control in Siam, conducting a liberation campaign which would culminate in the withdrawal of Burmese tutelage in 1593. The Portuguese merchants rapidly capitalized on the resurgence of Siam in order to resume trading in its ports. In spite of the paucity of information, this move is indirectly corroborated by the position of the Crown which, in an attempt perhaps to regulate Portuguese trade between Siam and Japan, established an official route between Malacca and Ayutthaya as a part of the system of concessionary voyages. 8

The grantee of the Siam voyage departed from Malacca in a ship laden with clothes from Bengal and cowries from the Maldive Islands, merchandise which was exchanged in Ayutthaya for sappan-wood, lead, deer skins, raw dyed silk and other goods, subsequently setting sail immediately for Japan. 9

The Siam voyage soon became an important complement to the major route undertaken every year between Goa, Macau and Japan, beyond doubt the most lucrative of the maritime trade routes exploited by the Portuguese in the Far East, since it permitted the presentation of a much wider range of merchandise in Japanese ports. For this reason, when confirmation of arrangements were not forthcoming, the captain of the second voyage took it upon himself to issue the command for its execution. The Siam voyage brought in nearly one thousand, five hundred cruzados and could be sold for the sum of five hundred cruzados if the respective grantee was not interested or did not have sufficient funds to carry it out independently. 10

It was possible to locate four licences for Siam voyages between 1584 and 1588 in the records of the Royal Chanceries, although it is probable that a number of other licences were granted in the East, since this was a voyage which could be issued by the Viceroy in India, whose registers did not reach Portugal. 11

INSTRUCTIONS FOR SIAM

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>INSTRUCTIONS FOR SIAM

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>

style="mso-spacerun: yes"> (AYUTTHAYA) VOYAGES

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>NAME OF GRANTEE

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>YEAR

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Nō OF VOYAGES

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Diogo Pereira Tibao

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>1584

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>2

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Luís Borges

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>1584

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>3

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>António Ribeiro

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>1586

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>3

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>Pedro Alves

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>1588

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>2

lang=EN-US style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt;font-family:

宋体;mso-fareast-font-family:黑体'>

|

style='font-size:10.5pt;mso-bidi-font-size:12.0pt'>

The arrival of new European nations in the Far East in the final years of the sixteenth century, chiefly the Dutch, would radically change this situation. In fact, the Dutch are known to have rapidly engaged in fighting with the intention of appropriating the commercial routes exploited by the Portuguese in the East, including the traffic with Japan, under the pretext that Portugal had become an enemy of Holland due to its incorporation in the Spanish Crown in 1580. Aware of the importance of Siamese merchandise in commerce with the Japanese empire, the Dutch immediately tried to gain access to the ports of Siam, and they succeeded in establishing a trading post in Ayutthaya in the year 1608.

The Dutch presence on the western Siamese coast and in the Bay of Siam certainly disrupted the development of the voyages between Malacca, Ayutthaya and Japan which, by all accounts, had ceased to operate by the beginning of the seventeenth century. 12 Two decades later, in 1625, and at the behest of the King of Siam, Song Tham (1610-1628), who was not greatly enamoured of the increasing Dutch dominion of the seas of the region, the Portuguese Crown endeavoured to re-institute the voyages to Ayutthaya. 13 This attempt cannot have met with much success, nevertheless, because no candidates came forward for the respective undertaking, doubtless deterred by the fear of loosing their goods to Dutch hands, 14 and there is no record of any voyage being accomplished until 1639, when the Japanese administration closed Japan to the Portuguese for religious reasons.

As regards private commerce between Siam and Japan, it certainly did not escape Dutch intervenation either, and in all likelihood it was abandoned during the first years of the seventeenth century, when the Portuguese merchants stationed in Ayutthaya preferred to dedicate themselves to shorter routes less exposed to the so-called 'enemy of Europe'. Only in the second half of the seventeenth century, after the signing of the Peace Treaty between Portugal and the United Provinces in 1669, did Portuguese traders from Siam begin to trade regularly with the Dutch in Batavia.

When Japan was closed to Portuguese traders, the importance of Siamese merchandise in the Japan trade was not forgotten. Indeed, the Portuguese authorities were well aware of it and they knew that commerce with Siam was one of the most important pillars on which Dutch trade with Japan rested. On launching a campaign during his governorship to induce the Asiatic rulers to close their domains to the Dutch, viceroy Dom Filipe de Mascarenhas paid special attention to Siam. He sent Francisco Cutrim Magalhães as ambassador to Ayutthaya in 1646 with the task of convincing King Prasat Thong (1629-1626) to expel the 'enemies of Europe' from his ports and to develop on his own account direct commerce between Siam and Japan. 15

This grand plan of Dom Filipe de Mascarenhas was aimed at destroying Dutch commerce with Japan, whilst simultaneously guaranteeing Portuguese access to Japanese silver by dint of the intermediary services of Siam, should the Japanese empire remain closed to the Portuguese. However, the plan met with no success whatsoever because King Prasat Thong, doubtless aware of the shortcomings of the Estado da Índia, did not expel the 'enemy of Europe' from his dominions. Japan was to remain closed to the Portuguese, and Portuguese commerce between Siam and the Japanese empire was never to be recovered.

LISBON, OCTOBER 21ST 1588

LICENCE FOR TWO JOURNEYS FROM SIAM TO JAPAN GRANTED TO PEDRO ALVES

LISBON, TORRE DO TOMBO NATIONAL ARCHIVES, CHANCELLERY OF DOM FILIPE I, PERQUISITES, BOOK 16, FOL. 207.

[1]Don Felippe etc: I make known to those who see this my Letter, that having Respect for the services which Pedro Alves has rendered me in the regions of India, I deem it good and it pleases me to grant him two voyages from Siam to Japan in the absence of those provided before the 12th of March of the preceding year of 1587, in which I granted him these voyages and they were included for him in the list dispatched the same year to the said regions; whereof he signed, as witnessed by don Duarte de Meneses of my state council and my viceroy; and he will have with each of the said two voyages all the profits and perquisites that those who before him undertook these voyages had and have and which directly appertain to him.

I hereby notify my present or future Viceroy or Governor of the Indian regions, and the Chancellor of my Exchequer therein, that as soon as in the said manner they can admit the same Pedro Alves into the said voyages, they will give him possession thereof and leave him serving therein one after another, having the profits and perquisites which directly appertain to him as said, without imposing any obligation or embargo whatsoever, because such is my grant. And the Chancellor of my Exchequer will cause him to swear on the Oath of the Holy Evangelist that while undertaking these [voyages], he will well and truly guard in all my service and the parts his right; whereof a record will be made in the margins of this [letter] which will be registered in the books of the Council of India and the enacting thereof at four months from this present date, and in the aforementioned list which is in India; in the record of this grant a note will be made by the appropriate official of how I made [the grant] through this letter, which goes by two routes, of which this is the first and accomplished, nullifies the other, in the copy of the aforesaid list it was duly noted how the said grant was effected.

Manuel Marques made it in Lisbon on the 21st of October of the year of the birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ one thousand five hundred and eighty eight.

Pero de Padua had it written.

[1] - In the margin "Pedro Alves".

NOTES

1 Details about the Portuguese embassies to Siam can be found in Maria da Conceição Flores, "Os Portugueses e o Sião no século XVI", MA Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Studies of the Universidade Nova, Lisbon, 1991, pp.26-31.

2 Idem, p. 35.

3 See Diogo do Couto, Asia, Decade V, Book 8, Chap. 12.

4 The Portuguese merchants who frequented the Chinese coastline certainly knew that it was easy to trade Siamese merchandise in Japan. In fact, although the ports of China had been closed to the Japanese by the Ming administration in 1480 owing to the numerous acts of piracy they were accused of committing, Chinese merchants continued to feed the great Japanese desire for the silks of the 'Celestial Empire', and for other merchandise including sappan-wood, ivory and deer hide brought by the latter from Siam, a kingdom they had traded with for many years, benefiting from the relationship of vassalage that had linked Ayutthaya to China since its constitution as a state. Thus, the voyage of António da Mota, António Peixoto and Francisco Zeimoto might not have been as accidental as Diogo de Couto leads us to believe.

5 To judge by the figures Fernão Mendes Pinto supplies us with in his Peregrinação, there were one hundred and sixty Portuguese in Siam (principally in Ayutthaya) around 1545 and in 1547 one hundred and thirty. See Peregrinação, chaps. 181 and 183. Diogo do Couto is more accurate and cites the existence of fifty Portuguese in the Siamese capital at the time of the invasion of Siam and the siege of Ayutthaya by the Burmese in 1549. See Asia, Decade VI, Book 7, Chap. 9. However, it ought to be emphasized that some Portuguese merchants may have abandoned Ayutthaya in fear of the consequences of the said attack.

6 See Fernão Mendes Pinto, Peregrinação, Chap. 183.

7 See Charles R. Boxer, The Great Ship of Amacon, Cultural Institute of Macau, Macau, 1988, p. 29.

8 The system of licensed voyages had become common practice by the second half of the sixteenth century when the Portuguese Crown, having little interest in instituting voyages at its own cost in the East, resolved to concede the respective licences to private individuals as recompense for services rendered. These voyages were carried out in private ships and the grantees did not receive any salary from the Royal Treasury. The licences were generally conferred for two voyages as a safeguard against any mishap that could affect the execution of the first. The grantee was not obliged to undertake the voyage, and could turn to the services of a third party or even sell the voyage if he was not interested in having doing it himself.

9 See Livro das Cidades e Fortalezas que a Coroa de Portugal tem nas partes da India, e das Capitanias e mais Cargos que nelas há, e da importancia delles, ed. Francisco Mendes da Luz, Centre for Overseas Historical Studies, Lisbon, 1960, ff. 97-98v.

10 Idem.

11 See Torre do Tombo National Archives, Chancelerias Regias, Chanceleria de Dom Filipe I, Doações, Book 4, ff. 313-314v., Book 5, ff. 157-158v., Book 15, f. 436 (a document already included in Maria Conceição Flores, op. cit., p. 289) and Book 16, f. 207. This last document is most interesting because it expressly refers to the licence of two voyages from Siam to Japan, hence it is transcribed in the appendix with my thanks to doctor Paulo Pinto who located the document.

12 See "Carta de D. Felipe III a D. Francisco da Gama, Lisboa, 20 de Março de 1625", in Maria da Conceição Flores, op. cit., pg. 293.

13 Idem. and "Carta de D. Filipe III a D. Francisco de Mascarenhas, Lisboa, 24 de Fevereiro de 1627", in Maria da Conceição Flores, op. cit., p. 294.

14 See "Carta de Francisco da Gama ao Rei D. Filipe III, Goa, 15 de Janeiro de 1626", Torre do Tombo National Archives, Documentos Remetidos da India, Book 22, f. 83.

15 See "Regimento para Francisco Cutrim de Magalhães que vai por embaixador ao Rei do Sião, Goa, 3 de Agosto de 1646", Portuguese Overseas Film Library, Livros dos Segredos, Book No. 1, ff. 83-84.

*MA in the History of the Discoveries and Portuguese Expansion (Faculty of Social Sciences, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon). Recipient of a research scholarship from the Orient Foundation.

start p. 17

end p.