When he arrived in Japan in 1577 1, João Rodrigues was a mere 17 years old. His initiation into adulthood coincided with his adaptation to the spheres of the real and the imaginary in the Land of the Rising Sun. His human and intellectual formation was largely wrought by contact with the people, language, culture and customs of Japan.

Rodrigues studied under the guidance of the Jesuits2 in a period when the policy of missionary adaptation proposed by Alessandro Valignano was beginning to take effect among the newcomers. In his first inspection of the Japan Mission (1579-1582) the Visitor had argued that the missionaries ought to study and speak fluent Japanese and assimilate local customs. It was therefore essential that the curriculum of the colleges embrace the teaching of Japanese literature, mores and ceremonies.

João Rodrigues is perhaps the most salient example illustrating the pertinence of this policy of adaptation. Given that he had a good grasp of the language and an in-depth knowledge of the country, he was chosen on various occasions to act as interpreter for the Superiors of the Mission. 3 His career as interpreter led him to live at close quarters with the most powerful men of Japan, Hideyoshi in particular, who frequently summoned him to the palace and spent long afternoons in conversation with him. 4

This involvement of more than thirty years with Japanese society gave him a broad knowledge not only of its customs and government, but also of its history.

It is precisely the History of Japan as told by João Rodrigues that we intend to analyze in the course of the present article.

HISTORY

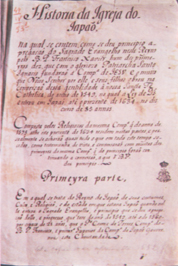

The cornerstone for our study will be a reading and commentary of the História da Igreja, 5 which is one of the most important sources for studying the Portuguese presence in the Far East and is probably the chief analysis of Japanese society and culture undertaken by a Westerner during the first century of Euro-Japanese contact.

Fróis analyzed this society in order to explain the history of the missionaries. 6 Valignano analyzed this society in order to justify the missionary model. 7 Rodrigues, in his turn, dealt with Japanese social organization, customs and values with the sole intention of spreading knowledge about Japanese civilization.

Three extracts of the História have come down to us. These are: the first introductory part, which deals specifically with Japanese civilisation, and of which we have only an eighteenth century version; the beginning of the second part, in which the author refers to the work of Father Francisco Xavier (we do not know if it is a seventeenth century version or if it belonged to the original); and the text from the seventeenth century, which describes the visit of Bishop D. Pedro Martins to Japan. 8 The truly innovatory and even modem chapters of his work are to be found in the first part. These are chapters in which Rodrigues turns to a predominantly sociological treatment of the country. He describes with detail and noteworthy discernment the living quarters, attire, physical appearance, mores, ceremonies and arts of the Japanese people. However, before addressing the customs, the author deems it fitting to describe Asiatic and Japanese geography (chapters 1 to 6) and to make a brief incursion into the history of the country9 by providing a geographical and historical background.

Rodrigues divides the history of Japan into distinct periods, characterising them in an attempt to distinguish their internal relationship. He bases his work on direct observation, old historical accounts and the knowledge he built up over long years of living with the Japanese. His is an attempt to "state the truth of what is happening".10

The periods we shall look at take in three distinct phases. Firstly, there is a look at the origins of the country, presented because, up till that point the Jesuits had only "written about the second and the third [periods]"11, and had not given readers an overall idea of Japan's development. Contrary to what the Society of Jesus had done, Tçuzzu12 writes about all the periods.

Scenes of Japanese life and customs at the time of João Rodrigues.

Scenes of Japanese life and customs at the time of João Rodrigues.

In chapter 11 of his História, João Rodrigues states that the first phase lasted from the appearance of the first king, Jimnu, in the seventh century B. C. and the first contact between Japan and China, until A. D. 1340. The second period lasted from 1340 until 1582 when Hideyoshi entered the Tenka government. 13 The third period began in 1582 and lasted until 1620. 14

THE FIRST PERIOD

João Rodrigues leaves to one side the prehistoric periods which were not included in court histories. He takes as his point of departure the period of chieftanships which were regarded as the beginning of the Japanese State.

What characterizes the first period, according to Tçuzzu, is the fact that the whole country was subject to royal authority ("the kingdom was governed by a legitimate lord and ruler, and the whole of it obeyed the true king") and there was a general consonance of customs and rites. 15 The highest echelon of the social hierarchy was occupied by two distinct groups: those who belonged to the patrician order, which governed the kingdom; and those who belonged to the military order, which defended the country under the command of the Shogun - the captain general and constable of the kingdom. For a term of three years or more, the king would send governors to the sixty eight states16 into which the country was divided for administrative purposes, and he appointed captains and garrison soldiers to administer justice in the various provinces. It fell to the monarch and governors to pass sentence on the crimes.

During the first period, social mobility was only possible within the highest echelons; "in this age the peasants and commoners always remained commoners".17 Only the sons of the nobles could advance by their services "to the various ranks of nobility and offices of the royal household".18

The king gathered "most substantial" revenues and taxes from the entire kingdom and the lords enjoyed the lands and revenues which the king bestowed on them by way of royal grant.

Idolatry passing from China and Korea spread throughout the entire country. Sumptuous temples were constructed as well as monasteries and universities "some of which had three thousand monasteries or dwellings with their superiors and disciples".19

COMPARATIVE TABLE

COMPARATIVE TABLE

style='mso-special-character:line-break'>

|

DIVISIONS OF JAPANESE HISTORY

ACCORDING TO FRANCINE HÉRAIL

Ⅰ.Proto-History

1.Chalcolithic

2.Epoch of the Great Tombs

Ⅱ.Antiquity

1.Asuka Period

2.The Regime of Codexes

3.Post-Heianic Period

Ⅲ.Middle Ages

1.Kamakura Period

2.Restoration of Kemnu

3.Muromachi Period

Ⅳ.Modern Period

1.Azuchi-Momoyama Period

|

C3rd B.C.-C3rd A.D.

C3rd-end of Cr4th

583-710

710-mid-C11th

mid-C11th-1185

1185-1333

1333-1336

1336-1573

1573-1603

|

PERIODS OF JAPANESE HISTORY

ACCORDING TO JOÃO RODRIGUES

1st period(C7th B.C.-1200/

1340)

2nd period(1200/1340-1573)

3rd period(1573-1620)

|

Throughout this period, the Japanese lived in peace and prosperity. Their customs, nobility, buildings and royal splendour flourished. The ancient chronicles and architectural ruins bear witness to this. 20

The characterization Rodrigues gives of the first period of Japanese history is heavily influenced by the angle provided by the court. He offers us two thousand years of history in which the social and political organization remained unchanged. What prevails is a king who rules over the entire land, a strong central power, a body of civil servants recruited from the leading families, an administration of the provinces which was essentially geared towards collecting taxes, a society hierarchical in the extreme.

The characteristics ascribed to the first period are not uniformly applied to the twenty centuries covering the period 660 B. C. to 1340 A. D.. During this lengthy period of time, which spans in effect the end of the Neolithic Period to the Kamakura Era, various structural modifications refashioned Nipponese society. If we adhere to Francine Hérail's periodization, it will be noted that only the period of the Great Reform (at the end of the seventh century, and the beginning of the 8th) approximates, although precisely, to the first stage described by João Rodrigues.

The origins of the Japanese state do not go back to the seventh century B. C., as a reading of the História gives to understand. Such origins are rather more recent. Rodrigues must have had access to the first official chronicles of Japan, compiled in the eighth century, when the beginning of the historical epoch was linked to the advent of the first human emperor, Jimnu Tennô, in 660 B. C. 21 However, in the present day, Jimnu is thought to have been the first chief to reach the Yanato region and impose the authority of his tribe on part of that plain in the middle of the third century A. D. 22

During the Epoch of the Great Tombs (third century, end of the 4th century), Japanese society proceeded to adopt the structure of a hierarchical cheifdom,. According to Kenzaburô Torigoe, Jimnô was the first of ten chiefs of imperial lineage to contribute to this transformation. 23

The Yamato reign has absolutely nothing in common with the first period described by Rodrigues, Certainly, among the ideas imported from China came that of creating a centralized state and the Korean venture indeed provided the Japanese governors with a motive for shoring up their powers. Nevertheless, Japan was far from constituting a national unity under the authority of an emperor. The land was divided among clans (uji) who enjoyed much autonomy. The spirits of the forebears were worshipped24, reinforcing the internal solidarity of the group and frustrating attempts at centralization.

As the Yamato kingdom grew in size, it became necessary to establish an administration covering the entire land. The sixth century was marked by struggles between the oldest powerful clans, linked tothe chieftain system (Nakatomi, Otomo and Mononobe) and the Soga family - a family in ascendance and interested in increased centralism. The Soga family overthrew their rivals and in 592 succeeded in enthroning the empress Suiko. Henceforth the kingdom of Yamato progressively took the shape of a state governed by written law. The sinicization of the country grew more emphatic.

In the two centuries that followed, the assimilation of the Chinese model went hand in hand with desire, on the part of the governing bodies, to see themselves established as authentic chiefs of the entire territory, rendering asunder the local authorities embodied in the clans.

Prince Shôtoku-Taishi (574 to 622), who was heir to Suiko and upon whom affairs of the country were incumbent, played a prominent role in the institution of centralizing principles imported from China. Amongst these principles figured that of adopting an outside religion - Buddhism 25, and the diffusion of the Confucian notion of a single central authority.

In the middle of the seventh century the Soga family lost its ascendancy in the imperial household. The new governors were thus free to forge reforms of a genuinely radical nature. Prince Nakanôoe (named heir upon whom the affairs of the country were incumbent, as was the case with Shôtoku-Taishi) and a number of former students who had lived in the Celestial Empire, sought to put into practice a socio-political system copied from the Chinese model.

The following measures feature among these brought in the Great Reform: the reaffirmation of imperial primacy (that is, the shoring up of the power of those who, fettering the emperor, concentrated his powers in their own hands)26; the consolidation of the civil service system by means of admission exams for public office; the division of the land into provinces subject to the capital; the nationalization of the land and its egalitarian distribution; and fiscal reform.

Japan underwent a gradual reorganization, from the centre (areas directly subject to the court) to the periphery (areas until then dependent on the clans). This process was completed between the end of seventh century and the first decade of the eighth century with three further innovations: the first legal code was definitively drawn up (701); the units for measurement were uniformly standardized; and coins were minted. In 710, the court settled in Nara, a city expressly built to act as the seat of central power. The imperial household retained for some brief decades executive power, having recourse to endogamy, which furnished a degree of independence in relation to the most powerful clans.

However, even within the course of the eighth century, this panorama began to change, ushering in a new era. The Fujiwara clan gained great influence at court; dominions appeared and disappeared; the bonds of patronage multiplied.

By 774, twelve of the seventeen high dignitaries of the court were members of the Fujiwara clan. Their tactic consisted in marrying women of their lineage with future emperors, who would subsequently be deposed and substituted by young princes who were sons the Fujiwara princesses. The grandfather would assume regency. Once the power of the clan was consolidated, the kampaku was established -a regency in the name of the adult emperor- a title which had its debut in 887.

Between 897 and 1086, the height of the Fujiwara hegemony, the latter busied themselves securing immediate power and crucial openings, manipulating the emperors and monopolizing the highest offices of the administration.

The imperial family and the court demonstrated a degree of force with the implanting of the system of legal codes, the division of the land into provinces and the agrarian system associated with fiscal reform. However, the geography of the country and the very structure of rural communities impeded the wholesale adoption of the Chinese model.

The former owners of the land were now governors of the districts. Officially they had forfeited possession of the land, but they acted as its authentic lords, bridging the gap between the civil servants of the central power and the local populations.

However much the State was desirous of entering into a relationship with the individual, Japanese society retained a structure based on the family and the community. This gradually led to the reawakening of regionalist tendencies. At a distance from Heian, the capital as of the end of the eighth century the land experienced fragmentation under the authority of powerful local lords.

Not unlike what was taking place in the countryside, in the capital also personal links began to prevail over respect for the law. The heights of the Fujiwara epoch ushered in the demise of centralism and the end of the system of codes.

At the end of the eleventh century the Fujiwara tactics for controlling the imperial family lost ground, and the emperor took advantage of the occasion to retrieve his authority.

In 1086, after the death of Goreizei-Tennô, there was no Fujiwara grandson to succeed him. The new emperor, Gosanjô-Tennô, following the "technique" of the Fujiwara, abdicated and placed his son Shirakawa-Tennô on the throne. Now the retired emperor was father of the reigning emperor, and had greater influence over him than the grandfathers.

Shirakawa inaugurated the governments of the retired emperors; having abdicated in 1086, he was the mentor of three successive emperors. Although the kampaku had not been abolished it was deprived of power ("the spell turned against the sorcerer"!).

The emperors' recuperation of power was temporary. The political system finished in ruin as a result of rivalries between the various pretenders to the throne and the struggles between local lords and the representatives of the court.

The rise of the warring families associated with the context described above was to be the source of radical changes in the political organization of Japan. Disputes over political power began to be conducted by means of war. For the first time, in 1159, a warrior, Taira in Kiyomori, dominated the capital. He nevertheless sought to govern the country as a member of the patrician order: he had recourse to the customary policy of weddings with members of the imperial family, rather than developing the links of solidarity and personal dependency with other warriors who would assure him of maintaining power.When the emperor decided to get rid of him, the warriors, led by Minamoto in Yoritomo, opened the way for the Japanese Middle Ages. 27 For the next four centuries, Japan would be governed by men in arms.

THE SECOND PERIOD

João Rodrigues, in his "Foreword to the Reader", states that the second period begins in around 1200 and ends with Nobunaga. These time frames fully correspond the Japanese Middle Ages (1185-1573) cf. comparative table. However, in chapter 11, he puts back the beginning of the second period to 1340 when Ashikaga Taka Uji is named Shogun.

If, on the one hand, 1200 is the date which most readily adapts to the periodization proposed by Francine Hérail, on the other, it is interesting to observe that 1340 is closer to the passing of the shogunate into the hands of the Ashikaga (1338) and consequently, to the emphatic breakdown of central authority. 28

Rodrigues claims that only at this point was there any de facto usurpation of royal power29 by Ashikaga Taka Uji and other captains, "leaving the king and the patrician order deprived of government, revenue and the lands that they guard"30 The absence of a central power proved conducive to increasingly widespread conflict and entrenched anarchy: "the whole of Japan was at war destroying each other... each man for himself".31

The king and the patrician order remained in the city of Miyako "confined and extremely poor with no revenue for their support, other than that which was given them by those who possessed the kingdoms, and the Shogun of the like by means of the honours [the king] bestowed. 32 João Rodrigues attached great importance to the fact that although they had usurped the government, the lands and the revenues, the warriors always recognized the king as their legitimate lord. No Shogun ever dared wrest the title from the emperor.

The second was a period of destruction (of the royal and patrician palaces, of the cities, of the harvests), of poverty and insecurity. Trade diminished, whilst on the land and sea routes there was a proliferation of thieves, bandits and pirates. In the absence of central government and in the climate of lawlessness, crime and teachery were rife, and retribution arbitrary.

When, in 1549, Father Francisco Xavier arrived in Japan, the second period was still under way.

In the História do Japão by Luís Fróis, there is frequent allusion to the civil war which serves as a background for the activities found in Chapter 2 of the First Part, when Fróis states that in 1549 Shimazu Yoshihisa, daimio of Satsuma, declined to assist in the removal of Xavier from Kagoshima to Kyoto on account of "some wars that there were in his kingdom".33

This author describes the civil war from the vantage points in which the missionaries were stationed (Kyushu and Kinai). However, the confrontations extend throughout the entire territory. It was an all-embracing process. The military groupings were not stable; the alliances were provisional, depending on the governing interests of the day.

Oda Nobunaga (1534-82), in a portrait by Kano Motohide. (Aichi Prefecture)

By virtue of the História by Fróis, we have some notion of the importance of the prestige of the great warriors as a binding element for coalition34, at a time when power was highly unstable.

Although João Rodrigues cites 1340 as the beginning of the second period, the crisis of Japanese central power has its origins in the middle of the twelfth century, with the crisis of 115635 and the subsequent introduction of the Bakufu36 (1185-1333). The warriors assumed power at this juncture, contributing to the progressively waning authority of the capital (that is, of the patricians).

From 1467 on -the Epoch of the Warring of the Provinces -, civil war became endemic, an the Shogun was practically altogether divested of executive powers, as had come to pass with the emperors. This period was marked by the absence of an acting central authority and by the rapid renovation, especially as of the sixteenth century, of the families of the daimyos. The daimyos came to function at a local level in a manner which was similar to that used by the court for the country as a whole in earlier epochs. The political carving-up of Japan thus grew more acute. Nevertheless, the task of inverting this process of the fragmentation of power was incumbent upon a single daimyo, strategically located in the centre of the country, gradually imposing his authority on an increasingly broad area of land. Oda Nobunaga - daimyo of Owari - took the first steps in this direction.

THE THIRD PERIOD

The third period into which João Rodrigues divides Japanese history coincides with the process of reunifying the country conducted by Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and Ieyesu (that is, with the Azuchi-Momoyama Epoch, cf. comparative table).

The author claims that the third period truly commenced only when Hideyoshi "completely subjugated the whole country".37 However, he does recognize that Nobunaga set the course for centralization.

In this period, social mobility was possible by means of armed service, the religious route or by families ties with the "Lord of Tenka". The laws, government or by customs were restored; new cities, palaces and fortresses were built; commerce flourished and seafaring saw great developments; the wealth and opulence was apparent in the attire and in the gifts offered during visits. Peace brought with it prosperity and abundance. The patricians once again became the lords of the kingdoms, enjoying new lands and titles.

Whilst throu-ghout the first and second periods the idolatry "imported" from China prospered somewhat (the Bonze possessed great revenues and magnificent temples), in the third period the Jesuit missionaries began spreading Christianity.

Unlike Fróis, João Rodrigues makes no reference to the arrival of the Portuguese in the Empire of the Rising Sun, but like him he makes no reference either to the bearing this fact had on the passage from the second to the third period of Japanese history. In effect, the spreading of the Gospel gave rise to new sources of division in the heart of Japanese society38, but the introduction of firearms into the country modified strategic concepts, aiding the action of the centralizing forces. 39 Oda Nobunaga knew better than his rivals how to take advantage of the potential of rifles and, by means of this revolutionary action, managed to invert the politicalmilitary process that had been dragging on for years, laying the foundation stones for the unification of the Japanese empire. By the time of his death in 1582, more than half of Japan was under his control.

Portrait of Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98). (Kodai-ji, Kyoto)

Previous pages: Battle of Nagashino, 1575 (details) - triumph of Nobunaga's tactical innovation, it indicates historically the triumph of firearms and the end of the Medieval Cavalry in Japan. Oda Nobunaga was the first to realize that heavy arms ought to play a defensive role. In order to maintain a continuous line of fire, he arranged the musketeers in three lines, corresponding to the three operational steps of the muskets: front loading, lighting the wick, aiming. Thus he stationed three thousand at the frontline of the combat in Nagashino.

(Tokugawa Art Museum, Nagoya).

Nobunaga protected the Jesuit missionaries, whereas he persecuted the bonzes. 40 He was well aware that the process of reunification would only take a smooth course if the focal points of private authority were terminated. Therefore he had to combat the Buddhist communities who dominated vast areas of Japan and their respective inhabitants.

Although Nobunaga's efforts were undertaken at the cost of successive wars against those who persisted in guarding their autonomy, the battles he waged during his lifetime shared the common denominator of extending of the power of a single warrior.

After Nobunaga's death, Hideyoshi succeeded in assuming leadership and brought to a conclusion the subjugation of the remaining Japanese territories between 1582 and 1591. The reunification of the country under his authority was immediately followed by an effort towards centralized bureaucracy: Hideyoshi ordered a population and cadastral census to be taken, "a means to determining the wealth of the country as a whole, establishing separate statutes for the warriors and the peasants, to better control both".41 In Hérail's words, "Hideyoshi established a kind of centralized feudal state. 42

His successor, Tokugawa leyasu, preserved a united Japan, one subject to a central power under his authority, and in 1603 he established the third bakufu.. Rodrigues gives us tidings of this transformation: "this third period after the death of the Taiko (Hideyoshi) underwent some change with the succession of Daifu (leyasu) who improved the kingdom and his state as regards housing and sustenance".43 Tçuzzu was above this event, which impeded his remarking on the deeper ruptures, but the actions of leyasu were to give rise to a long Shogun dynasty.

CONTINUITIES AND RUPTURES

Towards the end of chapter 11 of the História da Igreja do Japão, Rodrigues points to the similarities and differences of the three periods he described. He affirms that "the first is the proper and true Japan" the whole of the country is subject to the authority of the king; the second is "tyrannical and contrary to the first" - power was usurped by the warriors; and the third is, in part, similar to the 1st - a return to central power dominating the whole of Japan, living in peace and prosperity, but is also similar to the second -power was usurped by a single warrior.

Other authors of the Society of Japan who had written about Japan during the course of the civil war had no knowledge of what had come to pass previously. Thus they took this state of confusion and anarchy to be inherent to the proper and natural Japan. They thought that the country had lived in a state of continuous warring since its origins, lawless and void of central government. They concluded that although those in possession of the land were legitimate landowners, the Shogun was the king of Japan, and that the true king was a priest. 44 The image of Japan as a country permanently at war, stemming from an unawareness (or partial analysis) of Japanese reality, spread throughout the West by means of the letters of the Jesuit fathers and writings which employed these missives as their sources. 45

João Rodrigues sought to return to the origins of the Japanese state in order to better follow the evolution of the country. He presents us with a periodization imbued with the notion of degenerations and the loss of primitive qualities. The first period is the "natural" one, the "proper" and the "true" Japan, whilst the second and third fall away from the original model. This "falling away" took place when the warriors usurped "command" from the true lord46 and the central power was defeated. With the reunification of the country (third period), centralism was restored, but power did not return to the hands of the king.

It is interesting to note that the main characteristic attributed by the author to the first period (the entire land being subject to the authority of a single leader) is reconcilable only with the Period of the Great Reform. In the origins of the Japanese state, the emperors did not dominate the entire territory. This role fell to the clans. Even when imperial primacy was reaffirmed, between the end of the seventh century and the beginning of the eighth century, the intention was to shore up the authority of the court and not the emperor.

We can see that Rodrigues was clearly influenced by the perspective of the patricians. During the Ancient Period, the authority of the court was legitimized by the collusion (tacit or forced) of the figure of the emperor. It was the "power behind the throne", personified by the patricians, that in effect ruled the country.

The idea of creating a centralized state in Japan first arose at the beginning of the seventh century in the wake of the assimilation of the principal aspects of Chinese civilization (writing, thought, religion, administrative organization). The political centralization brought to bear in the Nara Epoch (710-middle of the tenth century) was the result of an effort towards sinicization. It was not an element that was "proper" and "natural" to the Land of the Rising Sun. The era and the isolation, however, donned a natural hue in the eyes of the patricians.

In chapter 11 of the História, Rodrigues attempted to fill a gap in the relations of the other missionaries, addressing the first period of Japanese history. However, it is in the description of this same 1st period that his analysis in fact reveals a number of shortcomings. In our judgement the author failed to perceive a fundamental dimension of the Nipponese political organization: the reigning emperors rarely wielded political power. This role was largely relegated to ceremonies and the arts. The description of the second and third periods, in turn, show that the author had in-depth knowledge of the period of the civil wars and the process of reunifying the country. Knowledge which came to him from the relations of the Jesuit fathers who had lived in Japan from the middle of the sixteenth century and also from direct contact with the Nipponese reality during the governments of Nobunaga, Hideyoshi and leyasu.

João Rodrigues' treatment of Japanese history is very brief and schematic, but it has the advantage of tracing the evolution of the Japanese state from its origin up to the moment when Tçuzzu leaves the country.

Rodrigues concentrated on the three periods into which he divided the history of Japan, and on overcoming the false ideas that circulated with respect to these periods. He wanted the Europeans to understand that the Empire of the Rising Sun had not always lived under the sway of the Emperors: the military conflicts and the anarchy had been only one moment in its historical evolution, and not a permanent characteristic. Before the warriors, the patrician class had governed the land. Japan, then, need never be defined again as a warring country.

The first pages dedicated by a European to the Ancient History of Japan are undertaken by Tçuzzu's hand. For the first time in the writings of the Jesuit missionaries, the Japanese Archipelago appears with a past. Beyond the chaos and the warlords.

NOTES

1In the História da Igreja do Japão, João Rodrigues states that he arrived in Japan "26 years after the Blessed Father (Francisco Xavier) had left Japan and departed for India". Since Xavier left Japan in November 1551, there can be no question about Rodrigues' having arrived in 1557. Cf. Michael Cooper, Rodrigues the Interpreter; an Early Jesuit in Japan and China, New York, Weatherhill, 1974, p. 38.

2Cooper proffers the hypothesis that Rodrigues arrived in Japan as an assistant to a merchant or an apprentice. However, he thinks it more likely that the boy had gone to that country under the protection of the missionaries. (cf. Cooper, op. cit., p.37). In 1580, Tçuzzu begins his novitiate in Usuki and the following year begins to study humanities in Funai. It is also in Funai that he commences his studies of philosophy (1583) and Theology (1585). Cf., Ibid., p. 66.

3Rodrigues was interpreter to Valignano in the Embassy of the Viceroy of India who visited Hideyoshi in 1591; he later undertook other diplomatic missions, in Tokugawa for example. Cf. Cooper, op. cit., pp. 73-75,191-192.

4Cf. Cooper, op. cit., pp. 82-83.

5In this study we are using the following edition: João Rodrigues, História da Igreja do Japão, a transcript of codex 49-IV-53(fols. 1-181) from Biblioteca do Palácio da Ajuda, prepared by João do Amaral Pinto, Notícias de Macau, 1954.

6Luis Fróis SJ, História de Japão (critical edition by José Wicki SJ), 5 vols., Lisbon, 1976-1984.

7Alessandro Valignano SJ, Sumário de las cosas de Japón (1583), (critical edition by José Lúis Alvarez-Taladriz), Tokyo, US, 1954.

8Josef Franz Schütte, "A História inédita dos Bispos da Igreja do Japão do pe. João Rodrigues Tçuzzu SJ." in Congresso Internacional de História dos Descobrimentos, Actas, 5 vols., Lisbon, vol. V, 1st part, pp. 297-328.

9"Before speaking of the customs of this kingdom (...) it is necessary to bear in mind (...) that there were three different periods in Japan (...) and we must now write about all three." In João Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, pp. 177-178.

10Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, p. 178.

11Ibid., p. 178.

12Tçuzzu is a derivative of the Japanese word tsuji, meaning: interpreter. Cf. Cooper, op. cit., p. 69.

13In the "Foreword to the Reader", however, Rodrigues had presented as chronological demarcation points of the first period the years 660 B. C. and 1200 A. D., and of the second period the years 1200 and 1582.

14The information gathered under the "Foreword to the Reader" is concomitant with that of chapter 11.

15Cf. Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, p. 178.

16In the Administrative Charter of Japan from the beginning of the Heian Era (824), the country is registered as divided into 68 provinces. Cf. Francine Hérail, Histoire du Japon. Des origenes à la fin de Meiji. Matérieux pour I'étude de la langue et de la civilization japonaise, Paris, Publications Orientalistes de France, 1988, pp. 82 and 83.

17Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, p. 179.

18Ibid., p. 179.

19Ibid., p. 180.

20Rodrigues states that "Marco Polo mentions the Japanese royal palaces" in his Book, Cf. Ibid., p. 180.

21In Japan, at the beginning of the eighth century, 60 year cycles began to be used to measure time. It seems that it was at this point that the ancient chronology of Japan was fixed, In effect, the year 601 was a "year of metal and the rooster", a combination which was considered to bring with it enormous changes, the beginning of a new era. On the other hand, the masters of the calendar recognized the existence of a kind of 'greater year' formed by 21 cycles of 60 years which gaves 1260 years. Now, this greater year would have been the measure used in the seventh century to recede 1260 years and establish the year 660 B. C., the date of the rise of Jimnu-Tennô according to the "Chronicles of Japan", as the departure point which officially initiates national history. Cf. Hérail, op. cit., p. 21.

22Cf. Ibid., p. 48.

23Cf. Kenzaburô Torigoe, "Between the Gods and the Emperors; a new reconstruction of the Early History of Japan", in Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyko Bunko, Toyko, No. 33, 1975, pp. 23-83.

24Shintoism (a religious spirit closely bound in with the Japanese) is a type of animism, in which recognition is given to the power of the supernatural forces of Nature and further to the spirits of the ancestors. This religion originating in the Land of the Rising Sun joined its inhabitants with the surrounding nature but also helped to bolster family ties. Regarding this topic, see, for example, Edmond Rochedieu, O Xintoísmo, Lisbon, 1982.

25Buddhism is a universalistic religion, unlike the cult of the clan divinities. Regarding this topic, see, for example Henri Arvon, Le Bouddhisme, Paris, PUP, 1979.

26Contrary to claims made by Tçuzzu, centralization in Japan almost always resulted in a reaffirmation of the power of the court and not of the emperor.

27As in the West, the Japanese Middle Ages was marked by internal wars, instability of the power base, the bolstering of the ties of personal solidarity, and a preponderance of warriors. Cf. Michel Vié, Histoire du Japon, Paris, 1983, p. 47.

28The second period of the history of Japan to which Rodrigues makes reference in chap. 11 is concomitant with the Japanese Middle Ages as of the shogunate of Ashikaga (i. e. the Japanese Middle Ages after the resounding failure of centralism).

29"in about the year of the Lord 1130 the first civil wars broke out (...) the seed of later rebellion; however, they never usurped the rule and dominion of the proper king, as later came to pass". Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, pp. 180-181.

30Ibid., p.181.

31Ibid., p.181.

32Ibid., p.181.

33Luís Fróis, op. cit., vol. I, p. 24.

34In relation to this topic, the following study was used: João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, A unificação política do Império Nipónico segundo a "Historia do Japão" de Luís Fróis, p.4.

35 This crisis begins in the court, but results in a war for political power.

36Taken literally, bakufu means "government of the garrison" in allusion to the general quarter where the Shogun administration made its base; by extension it designates the very regime and military institutions that governed Japan from 1185 to 1868.

37Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, p. 184.

38João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, op. cit., pp. 8-10.

39In this regard, consult: João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, A introdução das armas de fogo no Japão pelos portugueses a luz da "História do Japão" de Luís Fróis, Instituto Oriental, Lisbon, 1992.

40Cf. João Paulo Oliveira e Costa, A unificação política do Império Nipónico segundo a "História do Japão" de Luís Fróis, p. 5.

41Hérail, op. cit., p. 284.

42Ibid., p. 285.

43Rodrigues, op. cit., chap. 11, p. 190.

44Ibid., p. 184.

45Ibid., p.184.

46Ibid., p. 188.

*Graduate in History from F. C. S. H. of the Universidade Nova de Lisboa. Currently first year M. A. student in Contemporary History of F. C. S. H. at U. N. L.

start p. 103

end p.