As was proposed in the first issue, RC will have a regular section on "Anthology" and/or "Archives", which will comprise texts which merit publication or re-editing because of their documentary value. The following text was to be published in RC2 but had to be omitted due to its length. We are now pleased to present Luís Gonzaga Gomes, a great figure of Macau, to the public and to offer our readers a text which, more than being of historic interest, is a colourful story of turbulent intrigue. These events deserve a special place in the amazing chronicles of the Portuguese struggle against the hordes of pirates in the China seas.

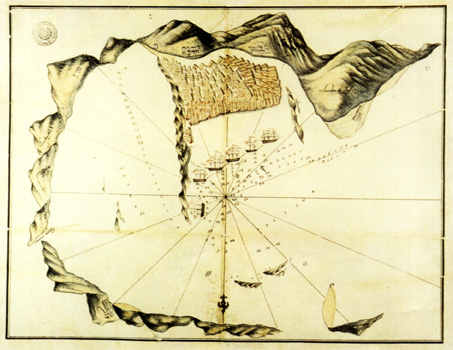

Map of the Naval Confrontation in Boca do Tigre

(c. 1810; painted manuscript; Overseas Historical Archives)

Shows naval combat between a Portuguese fleet of six boats, one hundred and eighteen cannons and seven hundred and thirty men and the pirate fleet of Kam-Pau-Sai of around three hundred war junks, one and a half thousand guns and around twenty thousand men.

Map of the Naval Confrontation in Boca do Tigre

(c. 1810; painted manuscript; Overseas Historical Archives)

Shows naval combat between a Portuguese fleet of six boats, one hundred and eighteen cannons and seven hundred and thirty men and the pirate fleet of Kam-Pau-Sai of around three hundred war junks, one and a half thousand guns and around twenty thousand men.

Kam-Pau-Sai had taken up piracy once more, having temporarily given up his idea of invading the mainland, when he discovered that the fearful Pereira Barreto had gone to Brasil. This convinced him that there was a fair chance of his becoming leader of the country. Consequently, he tried to instigate an uprising in Canton Province because that was where there was greatest discontent amongst the people and thus greatest opportunity of gaining support for his cause.

The Viceroy of Canton Province hurriedly attempted to organize an army and prepare a new fleet to counteract the incipient uprising and planned invasion of his territory.

On the 15th of August, 1791, the mandarin of Xiang Shan made an official request to the Senate of Macau to prepare and equip two ships to patrol the Lintin coast and assist the Chinese authorities to keep the neighbouring waters clear. The Senate did not wish to grant this request until it had been officially confirmed by the Viceroy of Canton Province and authorized by the emperor. The purpose of this was to oblige them, in return, to re-establish the former rights of the city such as constructing buildings without the authorization of the mandarins, the right to judge the city's Chinese delinquents and the freedom to visit Canton port at any time. In addition to this they wanted to be freed from the payment to the emperor of taxes which came from boats which anchored in Macau's harbour.

The negotiations stalled. There was fear that the mandarin of Xiang Shan would not be able to fulfill any of his promises and, in view of the fact that it had not been authorized by the emperor, the Senate wanted the Chinese authorities to fund the expedition.

In 1792, when the pirates had stepped up their activites, the mandarin of Xiang Shan made the same request again. The Senate replied that help would be given when the following rights had been recognized: the former entitlement of the Portuguese to the peninsula up to the frontier with China, Lapa (Ribeira Grande and Pequena, and Oitem) and Bugio Island; to allow Chinese people to live in Macau and to expel them when they misbehaved; to confiscate property' and goods from Chinese debtors in order to force them to comply with their obligations towards the merchants; to punish Chinese residents guilty of committing any crime and to sentence to death those who murdered any Christian; to allow residents of Macau to visit Canton and trade there freely provided they held a license issued by the Senate Attorney; for the Portuguese to present claims for compensation against any mandarin through the Attorney.

As usual, the mandarin was evasive in his replies and the negotiations failed again.

Kam-Pau-Sai took advantage of this period of calm to make up the losses inflicted by the ships "Princesa Carlota" and "Belisário" and then returned to his activities with such ferocity that the mandarin of Xiang Shan had no option other than to plead with the Portuguese for help. Governor José Lucas de Alvarenga discussed this issue in the Senate session of the 10th of February, 1810.

According to the vote entered in the minutes by D. António de Eça it is evident that the situation had worsened with the appearance of a new factor which could seriously endanger Macau's interests.

English merchants were supplying gun-powder, ammunition and other war materials to the pirates. Eager to obtain advantages and privileges from the Chinese in their trade, they made it known that they were prepared to help in the fight against the pirates. In fact, the English ship "Mercury" bearing the Union Jack arrived in Macau from Canton fully equipped to fight the pirates. Rumour had it that another English brigate was being prepared for the same purpose. Taking both this and the fact that there was an urgent need to restore public confidence and re-start trading activities which had been interrupted because of piracy into consideration, the Senate was forced to make a decision otherwise the prestige of the Portuguese would be damaged as well as possibly negative consequences which could follow the English intervention.

Magistrate Arriaga proposed that an expedition be organized with the Senate's brigate "Princesa Carlota" and the war ships "Belisário”, "Angélica" and "Conceição" whose owners were prepared to lend them for a month if the Chinese traders in Macau paid all the necessary expenses and the wages and food of the crew.

With this, the request of the mandarin of Xiang Shan was answered. The objectives of the expedition were:

1. to force the pirates to retreat into adjacent waters;

2. to open the channel for the benefit of trade and the public revenue and

3. to prevent the implementation of plans which would jeopardize the city's interests, such as the acceptance of help from the British. Magistrate Arriaga was of the opinion that priority should be given to eliminating any ideas encouraged by foreigners that the Chinese could question the ability of the Portuguese to defeat the pirates, ideas which were at that time delaying the completion of an agreement between the Viceroy of Canton and Macau.

The Government had chosen Magistrate Arriaga to negotiate an agreement with the Chinese authorities because of his dynamic personality and the fact that the Chinese trusted him. However, due to mutual distrust, it had been taking a long time to close the agreement. The distrust disappeared when the Viceroy realized, with horror, that trustworthy information which had been passed on to him had been proved with disturbing events and that the empire was in real danger not least from the Buddhist priests who supported Kam-Pau-Sai. They were in a position to subvert the entire country by destroying the people's confidence. Using superstition and intrigues, they could turn the people into dangerous fanatics capable of believing that Kam-Pau-Sai was the legitimate emperor of China.

Magistrate Arriaga held a position of great influence amongst the members of the Senate. They gave him carte-blanche to negotiate as he thought fit and he rewarded their expectations by convincing the Viceroy of Canton to reject the offer of free help from the British East Indies Company which was ready, at the beginning of 1810, to send a fleet to fight against the pirates. He also succeeded in persuading the Viceroy to start negotiations with Macau requesting the city to offer the same services and using him to represent the local authorities.

Arriaga then prepared an extremely detailed memorandum addressed to the Viceroy of Canton stressing all the advantages which would be gained from an agreement with the Portuguese. A Portuguese merchant acted as intermediary, taking the document to a trusted employee in the Viceroy's cabinet who arranged for it to reach the Viceroy. As soon as the memorandum had been duly received and Macau learned that the Viceroy had appointed three emissaries to go to Macau to negotiate with Arriaga, the intermediary was rewarded with the sum of fifty Patacas, at that time a considerable amount of money.

All aspects of the issue were discussed in great detail during the lengthy negotiations which took place in Macau. The end result was the following convention:

"Both His Excellency the Viceroy of Canton and Guangshi Province and the Governor of Macau are convinced that the Chinese pirates who plague the waters around Canton and Macau must be eliminated before public confidence and safe navigation in the area can be assured. They have both agreed to set up a coast guard service which will be equipped and manned by both governments. To this end they have appointed the following persons to act as their representatives: His Excellency the Viceroy of Canton has appointed the mandarins Chu, Pom from Xiang Shan and Shing-Kei-Chi from Nanpey; the Governor of Macau has appointed Miguel de Arriaga Brun da Silveira, Magistrate of Macau and Knight of the Order of Christ, and José Joaquim de Barros, Commander of the Police Force and Knight of the Order of Christ. After exchanging their respective symbols of office, they agreed on the following clauses:

Article I. A coast guard comprising six armed Portuguese ships in conjunction with the Imperial Fleet shall be set up immediately. It shall patrol from Paul, Boca do Tigre up to this city and from here across the gulf to Xiang Shan thus preventing pirates from entering the channels where they have been on the rampage, destroying and ravaging the coastal villages and towns.

Article II. The Chinese Government undertakes to pay the sum of eighty thousand taels for the expenses of the Portuguese ships. This sum shall be due even if the expedition fails.

Article III. The Government of Macau shall provide the crew, weapons, ammunition, etc. for the six ships with the greatest haste possible.

Article IV. Both Governments and their respective forces shall cooperate in carrying out this expedition.

Article V. All booty confiscated from the captured pirates shall by equally divided between the Portuguese and Chinese Fleets.

Article VI. All the former privileges of Macau shall be restored on successful completion of this expedition.

Article VII. This Convention shall be ratifed with the signatures of the official representatives of both Governments.

In testimony whereof, we have hereunto subscribed our names and applied our seals of office this 23rd day of November, 1809 - Miguel de Arriaga Brun da Silveira, José Joaquim de Barros, sealed by the mandarins Shing-Kei-Chi, Chu and Pom."

As was proved by the afore-mentioned vote registered by D. António de Eça, Magistrate Arriaga had tried to "protect the city, freedom of movement and national pride without incurring any loss to the public monies since the objective was to prevent the city from becoming a mercenary of an Asian nation, an action which would undoubtedly be contrary to the wishes of His Majesty the King and against the interests of the city. The City bore the costs for two ships while the Chinese contributed eighty thousand for the remaining four ships thus ensuring that the reputation of the City continued untarnished".

The eighty thousand taels from the Chinese Government was intended to pay for the crew, weapons and provisions over a period of six months.

When the Senate signed the agreement they were convinced that the six ships were only just adequate to fight against the pirates and exile them to adjacent waters. It was the Senate's belief that in order to defeat the pirates for once and for all, reinforcements would be needed. In view of this, on the 16th of November, 1890, a few days before the Convention was signed, the Senate wrote an urgent letter to the Viceroy of India requesting him to send the brig "S. João Baptista" captained by an officer who had already been in Macau with a crew of Portuguese and, given that there was a shortage of soldiers in the city, one hundred and twenty native soldiers to join a body of three hundred soldiers with officers from Portugal.

The Senate also requested twenty barrels of gunpowder, eighteen nine calibre cannons, six fourteen calibre cannons, six twenty four calibre cannons, twelve six calibre cannons, twelve eighteen and thirty six calibre howitzers together with the necessary equipment, five hundred rifles with bayonets and cartridge boxes, four hundred grenades, one hundred tarpaulins, fifty sail cloths, twenty five barrels of tar and hemp ropes. That which could not be carried by the "S. João Baptista" was to be transported on the brig "Activo".

On the 13th of March, 1807, the Prince Regent had ordered the Viceroy of India to send between one hundred and fifty and two hundred Portuguese soldiers to Macau on the frigate "Princesa do Brasil". Fearing that help would not arrive in time the Senate asked Manila to send Philippine sailors. This request was immediately fulfilled.

In the meantime, as the Senate was only in possession of one brig, "Princesa Carlota", another five ships had to be made ready in accordance with the first clause in the Convention. They were armed and crewed with around one hundred Portuguese and Macanese sailors, the only reliable men in the city at the time and six hundred and thirty Asians. The total expenses for the expedition amounted to twelve thousand Patacas and once the Senate's financial resources had been exhausted, Arriaga used his personal credit to obtain massive loans, from the major merchants, principally António Pereira Tovar and Felix José Coimbra.

Arriaga, invested with the powers of Superintendant of the Navy by Governor José Lucas de Alvarenga, fitted out the ships and prepared them to set sail within only five days. The British East Indies Company supplied a large proportion of the ammunition.

The Portuguese fleet consisted of the following ships: the "Inconquistável" weighing four hundred tons with twenty six cannons, a crew of one hundred and sixty men and skippered by Artillery Captain José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa; the "Conceição" with eighteen cannons and one hundred and thirty men commanded by Luís Carlos de Miranda; the "Indiana" with twenty four cannons and one hundred and twenty men commanded by Anacleto José da Silva; the "Belisário" with eighteen cannons and one hundred and twenty men commanded by José Alves; the "S. Miguel" with sixteen cannons and one hundred men commanded by Second-Lieutenant José Felix dos Remédios and the "Princesa Carlota" with sixteen cannons and one hundred men under the command of the famous António José Gonçalves Carocha. All in all there were one hundred and eighteen cannons and seven hundred and thirty men. Joined to the Chinese Imperial Fleet of sixty war ships with one thousand, two hundred cannons and eighteen thousand soldiers and sailors, this was the largest show of naval strength ever seen in the seas around Macau.

On the 29th of November, 1809, the fleet sailed out of Macau in search of the pirates. The pirates fled only from the Portuguese and not the Imperial Fleet. The Imperial Fleet stayed away from the action either because they supported the pirates or feared them. Some of the enemy junks which thought they were strong enough to fight against the Portuguese failed to escape. Some of them were burned, others were sunk. Around two hundred junks, the majority, were put to flight.

There was another battle on the 11th of December. This time it took place very close to Macau and the pirate fleet was divided into three groups. Once again the pirates failed to get the better of the Portuguese and, after losing fifteen ships, they were forced to take refuge in distant waters.

Very wisely, Kam-Pau-Sai realized that he could not afford to be weakened. He stopped sending his boats to collect money and food. Food was an essential asset as his fleet was composed of a huge number of men who would not suffer hunger in silence. Since he feared only the Portuguese, he sent emissaries to the Commander-in-Chief to propose a deal whereby the pirates would respect the Portuguese ships. Alcoforado rejected it indignantly and took advantage of the situation to demand that Kam-Pau-Sai surrender to the Emperor with the promise from the Chinese authorities that he would be pardoned and compensated with a high rank in the Imperial Fleet.

On the 18th of December Kam-Pau-Sai sent the arrogant reply that he feared nothing and added that he wanted peace with the Portuguese provided they did not interfere with his business.

In an attempt to persuade Kam-Pau-Sai's followers to surrender, the Chinese announced an Imperial decree on the 12th of January, 1810, promising absolute pardon for any of the rebels if they surrendered. Very few, however, responded to the promise of pardon.

In spite of all the intrigues and seductive promises made by the authorities, nothing could persuade the rebels to give in. The only effective method to change their minds was the strength of the Portuguese weapons.

There was another confrontation on the 15th of January. When A-Paul-Sai saw that a retreat was impossible he called an emergency meeting of all the other black flag chiefs. They were all in agreement that it was useless to try to resist the terrible Portuguese ships which were blocking their way out. They resolved to send emissaries to speak with Arriaga as they refused to negotiate their surrender with any other mediator. Under certain conditions they were prepared to hand over one hundred war junks and thirty ancillary lorchas along with eight thousand insurgents.

Arriaga succeeded in convincing the Chinese authorities of the advantages of accepting their surrender and made them comply with the rebel's demands.

New attempts were made to convince Kam-Pau-Sai to surrender but, despite the fact that his relative and right hand man had defected along with many other rebels, he himself had not given up hope. The attempts were to no avail. He continued to send his ships to fight against the Portuguese. His captains displayed remarkable heroism. When they could not escape they preferred to sink with their ships rather than surrender. Astonished with the heroic persistence of the valiant commander, Alcoforado tried once more to persuade Kam-Pau-Sai with new proposals, highlighting his courage and bravery as well as that of his men.

On the 26th of February Kam-Pau-Sai replied in the following terms:

"Yesterday I received a very persuasive message from you in which you state your desire to meet with me in Macau. I thank you for the compliment. I reign from the seas just as from the centre of a kingdom, wielding the sceptre of power and governing all those who obey me. I am therefore extremely busy. Government is no easy task and for that reason I am, unfortunately, unable to accept your invitation. At present my sole aim is to regain control of this territory and I shall not rest until I have accomplished it. I would be able to achieve my objective sooner if you were willing to lend me four ships. In return I should give you two or three provinces of your own choice. Please trust my offer. As regards the ships, if you cannot send them to me immediately then do so at your own convenience. Many people have advised me to surrender to a Tartar. These are nothing more than vain exhortations. While I am in command of this red flag fleet I shall do my utmost to gain the Imperial Throne. I have already ordered my fleet to sail to Boca do Tigre and defeat the usurpor's army. I have several other matters to communicate to you but I am not able to do so at present. The above should serve to inform you of my true intentions".

Had Alcoforado been able or had the Government of Macau agreed to help Kam-Pau-Sai to conquer the Chinese imperial throne, an easy task had the four ships been lent to him, Portugal's position in the East would have improved and the world political situation of the time would have undergone a great change. The Portuguese, however, were not, nor had they ever been throughout their history, interested in treason. They respected the Convention which had been signed by Arriaga and the representatives of the Chinese Government and left unturned a page of history which would otherwise have had profound and widespread consequences.

In view of Kam-Pau-Sai's refusal to surrender, Alcoforado realized that gentle persuasion was ineffectual and he returned to open hostilities.

Kam-Pau-Sai replied with a new strategy. He sent a small group of smaller and faster boats with the aim of distracting Alcoforado. Meanwhile the bulk of the fleet with better ammunition was sent to the narrow shallow channels where they could not be attacked by the Portuguese ships. With great caution Kam-Pau-Sai forced American and British gunners who had been captured together with their ships, to teach his crews how to use cannons in preparation for the decisive battle.

The cunning British traders continued to supply the pirates with ammunition and weapons in the hope that if the Portuguese were defeated then the Chinese authorities would be forced to turn to them for help.

The pirates believed that the 21st of January, 1810, was the most favourable day for them to confront the Macanese fleet. On the appointed day the latter was lying in wait off Lantau when a forest of masts draped with red flags appeared on the East.

Kam-Pau-Sai had decided to play his last card. He had brought almost all of his fleet: three hundred war junks, one and a half thousand cannons and over twenty thousand men lined up in three orderly divisions. This formidable naval power never seen before in the China seas was to be defeated by just six ships with one hundred and eighteen cannons and seven hundred and thirty men. The massive imbalance would have caused any commander to hesitate especially when the enemy forces were brave and hardy warriors who were accustomed to fighting to death. In addition to this they were led by a clever, courageous and desperate commander.

This was to be a fight of life or death. Arriaga was perfectly well aware that the future of Macau, Portugal's reputation and China's fate were all at stake. The enemy fleet was moving closer. Alcoforado, the bravest of them all, stood fearless and calm on the quarter-deck of the "Inconquistável", in complete control of himself and watching the pirates' boats with an eagle eye.

As soon as Alcoforado thought the right moment had arrived he waved his shining sword in the air as a sign to start battle. Immediately the air shook with the din of hundreds of cannons spurting out gunpowder.

The Portuguese ships advanced boldly within rifle shot distance of the first line of the enemy boats showing complete disregard for their defensive shots. At this distance a barrage of fire from the Portuguese artillery would have been enough to demast any of the boats and force them to flee. Some of the more daring pirate junks came alongside the Portuguese ships and put them under cross fire. Extensive deaths and damages were caused by the junks which poured out all their ammuntion from both directions. In the thick smoke it was impossible to distinguish between the ships of friends and foe.

Confident of his abililties as a strategist, Kam-Pau-Sai divided his fleet into six and sent each group to attack the six Portuguese ships separately. He was convinced that if they were isolated then they could be destroyed one by one. However, he did not realize the consequences of each of the Portuguese ships being situated in the centre of a ring of pirate boats. Firing from any angle the junks ran the risk of shooting at and damaging their own boats while the Portuguese ships had a much better chance of hitting any target as they were in the centre of the action.

At the height of the battle the "Conceição" was chased towards a reef where she ran aground. The pirates were delighted, sure that this was the beginning of a victory for them. When they tried to board the ship, however, the crew fought back fiercely and they suffered tremendous losses. Realizing that there was danger from all sides and that the ship was grounded, Luís Carlos de Miranda told his crew that there was no option but to comply with their duty and to give up their lives for the cause. The sailors gave up trying to manoeuvre the ship and grabbed onto weapons and loaded cannons in the fight against the enemy. After over an hour of intense fighting the pirates gave up hopes of defeating them. The rising tide and the light wind filled the sails of the ship and enabled her to dislodge herself and move into a better position beside the "Belisário".

It was António José Gonçalves Carocha, commander of the "Princesa Carlota", who was destined to make the decisive move. He had already carried out remarkable feats of bravery when, in the midst of the confusion he caught sight of the floating tabernacle or pagoda-ship through the dense smoke. Appreciating the effect which her loss would have on the superstitious pirates he lost no time. He turned on her and, despite the heroism displayed by all the boats which were escorting her, he did not stop until she had been sunk along with all the Buddhist priests who were on board. Carocha's outstanding feat completely demoralized the enemy. When they saw the debris of their gods exploding into the air they panicked and retreated in total confusion paying no attention to Kam-Pau-Sai's orders or his example. They fled into the shallow waters of Xiang Shan Bay where they could not be followed by the Portuguese. They were now, however, blocked at Boca do Tigre.

Shaken by this enormous and inconceivable defeat Kam-Pau-Sai had to face up to the fact that fate had dealt him a hard blow. His hopes and ambitions had been shattered.

He would never be Emperor of China. He decided to surrender on the 21st of February on the condition that Arriaga was present during the negotiations as the guarantor of the surrender agreement. Such was the prestige of the famous intermediary, one of the greatest figures in the history of Macau, that the Chinese had complete faith in his impartiality and sense of justice.

As soon as the authorities in Macau learned of Kam-Pau-Sai's decision, they tried at once to contact the Viceroy of Canton with the news. In turn he informed the Emperor of the good news in order to gain his permission to open the negotiations. In the meantime the pirate fleet was blocked in at Boca do Tigre.

When the Convention which allowed the Government of Macau and the Chinese authorities to cooperate in mounting the expedition against the pirates was signed, João Baptista de Guimarães Peixoto had just arrived in Macau. Arriaga had already completed his six year term as Magistrate and Peixoto was to be his replacement. Fearing that the plans would fail if Arriaga were not present, the Senate wrote to Peixoto requesting him to postpone taking up office in order not to prejudice the forthcoming enterprise.

When Peixoto received the letter he became so furious that, in spite of being ill, he demanded to be sworn in as soon as possible. He was staying in Arriaga's home at the time and it took all his patience and tact to calm Peixoto down. In the end Peixoto was sworn in on a day appointed by Arriaga.

Even though Peixoto had stated a few days previously that the expedition would still be directed by Arriaga, as soon as he was sworn in he joined forces with Governor José Lucas de Alvarenga to create obstacles in the organization of the expedition. When Kam-Pau-Sai was defeated Peixoto attempted to remove Arriaga from the surrender negotiations and replace him with the Bishop of Peking. The Bishop refused to participate claiming that the Viceroy of Canton did not know him and he was not familiar with all the details of the situation.

When the mandarins found out that Peixoto was trying to substitute Arriaga in the negotiation process they informed the Government of Macau that they would have nothing to do with Peixoto. Arriaga was the only one who had a complete knowledge of the affair and, apart from that, Kam-Pau-Sai had declared that he would surrender to none other than him. The Portuguese were of the same opinion. They had little confidence in the new Magistrate: his bad reputation in India had reached Macau before he did and his behaviour in Macau had turned people against him.

In the meantime, while Kam-Pau-Sai's fleet was blocked, Governor José Lucas de Alvarenga lost the valuable moment when he could have drawn the greatest advantages from the Chinese authorities. As is shown by the Senate report of the 30th of December, 1810, he was enjoying himself with the Viceroy D. Bernardo Jose Maria de Lorena e Silveira, Count of Sarzedas "sending orders to the Commander-in-Chief who was sensible enough to ensure that they were not carried out otherwise all the efforts put into the expedition would have been wasted".

During the period when his boats were blocked, Kam-Pau-Sai requested Alcoforado to give him the honour of visiting him as he wanted to have the pleasure of meeting such a distiguished general. Alcoforado was willing to meet the request as he also was very interested in meeting his opponent the pirate chief face to face. He ordered a boat to be prepared. His officers, however, reminded him of the danger of going to meet Kam-Pau-Sai alone: there could be a trap, he could be risking his own life to no avail. Alcoforado called a meeting of the other commanders and told them about the invitation.

They all agreed that he should not accept Kam-Pau-Sai's invitation. Alcoforado did not know the meaning of fear and told them that he was very grateful for their concern but he could not turn Kam-Pau-Sai down. He believed the Portuguese reputation was at stake. The pirates would interpret any refusal as faint-heartedness from him and as the first sign of weakness from the Macanese fleet.

Alcoforado asked them to take revenge if the pirates killed him, said farewell to everybody and fearlessly boarded the boat which was to take him to the enemy fleet.

Absolutely calm, his face expressing no emotion whatsoever, he passed by the first pirate boat with no problem. He continued up to Kam-Pau-Sai's junk where he was welcomed with the clashing of cymbals and a gun salute. Kam-Pau-Sai received his guest at the gangway with great deference and, according to Chinese custom, he led Alcoforado by the hand into his cabin whereupon they both exchanged the most charming pleasantries. Whether it was because he wanted to surprise Alcoforado and impress him with his gallantry, or as a gesture of genuine admiration for his opponent, Kam-Pau-Sai wanted to show his indebtedness at having been honoured with a visit from the Commander-in-Chief of the Macanese fleet, he offered to free all the American and British soldiers who had been serving as gunners either because they had been forced into it or because they had been seduced by the promise of precious rewards.

Kam-Pau-Sai assured Alcoforado that having been on the receiving end of the Portuguese' bravery and courage, he had no desire to have them as enemies. He also hinted that it would be easy for him to break the blockade and risk another battle in order to escape with his swiftest boats to waters where they would be safe from the Portuguese. However, the honour of the visit had made him so delighted and he held Arriaga's promise in such high esteem that he was resolved to surrender with all of his fleet.

Alcoforado repeated Arriaga's promise. He regretted that personally he was unable to accept the surrender but he would do everything in his power to please Kam-Pau-Sai. He also added that he had orders to destroy Kam-Pau-Sai's fleet should he try to break the blockade.

They carried on a cordial exchange, each trying to outdo the other in etiquette and finally Alcoforado was unable to prevent Kam-Pau-Sai from accompanying him to his boat. When he returned to his ship all the Macanese fleet gave him a gun salute and the sailors climbed up the masts to greet him.

In the meantime Arriaga had gone to Xiang Shan in the lorcha "Leão Temível". In a meeting with the Viceroy of Canton and other imperial emissaries and mandarins from the province it was agreed that Kam-Pau-Sai's surrender would take place in Macau. It was also agreed that the pirate fleet would display their red flags as far as the Barra Fortress where they would then be lowered. Unfortunately the Government of the time was led by Captain José Lucas de Alvarenga, a graduate in Law from Coimbra University, a feeble but vain man from Minas Gerais who proudly emphasized the fact that he was the first Brasilian to govern Macau. In his heavy and ponderous Account of the Six Month Expedition (1809-1810) Organized by the Government of Macau to Help the Chinese Empire Fight the Chinese Insurgent Pirates (Rio de Janeiro, 1828), Alvarenga arrogantly claimed exclusive credit for the glory of the victory over Kam-Pau-Sai.

Alvarenga, possibly motivated by jealousy, forgot the interests of Macau and Portugal. His cowardice and stupidity prevented the population of Macau from enjoying the great victory of the Macanese fleet.

José Ignácio Andrade visited Macau twice and in his Account of the Victory of Macau over the Chinese Pirates (2nd edition, Lisbon, 1835), written and published in José Lucas de Alvarenga's lifetime, he described him as "a coward and inexperienced in Chinese customs". He considered Alvarenga's fears that Kam-Pau-Sai would attack Macau once his ships had reached the Inner Harbour as totally unfounded.

In view of this, Arriaga was obliged to carry on the talks outside the city walls in the Mong Ha Pagoda. This pagoda later became famous as the place where the first Sino-American treaty was signed in 1844. Arriaga called a meeting with the mandarins Chu and Pom and together they agreed on the day on which the Emperor's representatives were to meet in Xiang Shan.

Arriaga was received at the meeting with great pomp and honours. During the meeting the mandarins learned the news of Alcoforado's astonishing bravery. The Chinese authorities were amazed that he had gone to meet Kam-Pau-Sai. This, and their deep respect for Arriaga, led them to agree with almost everything he suggested.

In the end they decided that the surrender should take place in Fu Iong Sa near the city of Xiang Shan. Kam-Pau-Sai was to appear there with all his fleet. The Governor of Macau was to instruct Alcoforado to lift the blockade. As usual, however, Alvarenga delayed in giving the order.

By the following day Kam-Pau-Sai had already been informed by the mandarins that he should leave with his fleet for Xiang Shan. When they weighed anchor and started to sail towards the agreed location Kam-Pau-Sai saw that the Portuguese fleet was manoeuvering in a hostile manner. Alcoforado had still not received any instructions from Governor Alvarenga to lift the blockade and he thought that the pirates were attempting an escape. This mistake could have had disastrous consequences had Kam-Pau-Sai not realized that there was some kind of misunderstanding and ordered his ships to anchor again.

When the delegates at the meeting heard of this misunderstanding, Arriaga was rushed to Macau to convince Governor Alvarenga that his fears were unfounded. At the same time the Chinese delegates decided to meet Alcoforado and inform him of the decision which had been made with Arriaga.

When Alcoforado saw the two respectable Chinese men dressed in long yellow tunics come on board his ship, he immediatedly realized that they were persons of high rank since only members of the imperial family were permitted to wear that colour. They were treated with the greatest courtesy. The two representatives asked Alcoforado not to jeopardize the promise which had been made by them and Arriaga and to allow Kam-Pau-Sai to proceed to Fu Iong Sa with his fleet.

Alcoforado replied that he was greatly honoured with their visit and he had every wish to be of assistance to them but he could not violate the military laws of his country. The Government had ordered him to attack the enemy's fleet if it tried to escape and he would do so unless his Government ordered him to do otherwise.

The mandarins insisted in their request and advised Alcoforado that most of Fuquien Province supported Kam-Pau-Sai. This province was populated mainly by seafarers who could easily equip a new fleet to break the blockade and continue the war.

Meanwhile, Arriaga's visit to Governor Alvarenga had paid off. After lengthy arguments he had convinced him to allow Kam-Pau-Sai's fleet to leave. He persuadded him to send the orders to Alcoforado. The orders reached Alcoforado while the Chinese representatives were still on his boat.

When the mandarins heard that the orders had come from the Government of Macau they were very pleased. They took leave of Alcoforado and returned to the meeting place where they met Arriaga. As soon as he had convinced Governor Alvarenga of the need to lift the blockade he had gone back to the meeting place to tell the mandarins of the good news.

Following the lifting of the blockade Kam-Pau-Sai saw no reason to change his mind despite the misunderstanding. He accepted all the explanations which were offered with no sign of hard feelings. On the next day, the 12th of April, 1810, he went to a previously agreed place to start discussing his surrender.

The reasons for his surrender are still unknown. Kam-Pau-Sai was the leader of insurgents and pirates and up to that point had shown no fear of fighting. Although his fleet had suffered some damage it would still have been able to break the blockade. He could also count on help from the strong division which he had sent to Fuquien to collect taxes. When it returned the small Macanese fleet would have been under attack from both directions. Despite all of this he still decided to surrender himself and his fleet. Could it have been that his conscience finally told him to stop the useless sacrifice of more men? This is highly unlikely as Kam-Pau-Sai had never had any scruples whatsoever about attacking and ransacking villages quite heartlessly or capturing and looting Chinese or foreign ships.

Was it superstition? The sinking of the pagoda ship could have made him believe that the gods had deserted him. Another reason may be that he had finally been convinced that he would be better off accepting the post of a high-ranking mandarin in China and collaborating with the rulers of the country rather than continuing with his adventurous life as a pirate and a rebel.

The last reason was probably the most likely. He could surrender once he could take advantage of the solemn promise made by the Chinese authorities to make him admiral of the Imperial Fleet, a promise which was guaranteed by Arriaga in whom he had total confidence.

In spite of being a pirate leader, the mandarins treated Kam-Pau-Sai very courteously. Hence, when Kam-Pau-Sai's fleet anchored in Fu Iong Sa the Chinese authorities sent messengers to greet him and to invite him to take part in the surrender negotiations. When Kam-Pau-Sai entered the meeting room he immediately went up to Arriaga who was easily recognizable because of his different clothes and physical appearance. He told him that there were serious reasons which had led to his surrender and to negotiate with him. In accordance with Arriaga's promise he was prepared to exchange his life as a rebel leader for that of mandarin. He added that he was delighted to have the opportunity of meeting Arriaga in person.

Kam-Pau-Sai then turned to the mandarins. He told them that as they had already experienced his terrible strength over fourteen years, that he had only been defeated because of the Portuguese forces then he hoped they would treat him as a free and fearless man. Once he had had his say he sat down and listened to the conditions which were to be imposed.

During the discussions he was told that it would be necessary to impose a severe punishment on some of his cruellest and most wicked men. Kam-Pau-Sai had no objections to this and offered the names of fourteen villains whom he considered should be beheaded for committing atrocities without his consent.

Once this matter was settled the negotiations ended quickly. Kam-Pau-Sai confessed that he still had another eighty war junks which he had sent to Fuquien to collect taxes before going to attack the Macanese fleet. He would order them to come back and surrender. Viceroy Pak of Canton then read him a decree whereby all his crimes and those of his men were forgiven and which declared that from that day on they would all be treated as loyal subjects of the Empire.

It is not known what led Arriaga to behave as generously as he did when the confiscated goods were shared out. Some say he demanded no more than one thousand, two hundred of the pirates' cannons which were sent as a gift to D. João VI to be used in the battle against Napoleon. Others say that Macau received only fifty cannons. The fact remains that, according to Article V of the Convention, there should have been an equal division of the goods.

In his book "Historical Sketches of Portuguese Settlements in China", Andrew Ljungstedt who was in Macau at the time related that "the fifty bronze and iron cannons which Arriaga sent as a gift to the Prince Regent of Portugal were not war booty even though Andrade claims the opposite. They were the cannons which had been purchased to arm the chartered ships which took part in the expedition against the pirates. Nor were the cannons sent on the "Ulysses" as Andrade says but instead on the "Maria I". It is said that the cannons were not even worth the freight paid for them in Rio de Janeiro.

Bearing in mind that Macau had been forced to maintain war ships to fight the pirates since 1801 and that the maintenance costs were an increasing burden each year with a peak in 1810, not even half of the booty, that is one hundred and eighty boats, one thousand, six hundred cannons and three and a half thousand guns, would have been sufficient compensation for the costs which the city had incurred from 1804 to 1810 (370,000 Patacas). The share to which Macau was entitled would have been sufficient to pay off some of the debts which had been incurred".

Kam-Pau-Sai surrendered with exactly two hundred and eighty junks, many of which must have been loaded with loot, sixteen thousand men, five thousand women, seven thousand swords and spears and one thousand, two hundred cannons of various calibres.

This was all handed over to the Chinese without so much as a word. If Kam-Pau-Sai had surrendered in Macau rather than in Fu Iong Sa things would certainly have been different. Thus the Chinese did not comply with Article I of the Convention which required the imperial fleet to cooperate with the six Portuguese ships in defeating the local pirates. Not a single boat from the imperial fleet was present at any of the confrontations with Kam-Pau-Sai and yet they were the only ones to benefit from the treasures.

The following letter, from the Senate to the Viceroy of India on the 30th of December, 1810, gives a clearer picture of the difficulties which were encountered during the negotiations. Referring to the obstacles created by Peixoto and Alvarenga the Senate wrote that "Arriaga believed that the public interest would be prejudiced if the matter were disclosed. In the name of his King and country he requested that he should be provided with a boat. There would have been a public outrage had the Government refused his request so he was given the "'Princesa Carlota". Despite the fact that he had no permission from the Government, he set off immediately to meet the Viceroy of Canton and from there went directly to A-Pau-Sai's flag ship.

There he encountered new obstacles with the subaltern Mandarins. He suddenly fell seriously ill and was obliged to return home. Unable to conclude his deal with the Viceroy of Canton, A-Pau-Sai left Boca do Tigre in exasperation with his fleet and headed for the village of Hy-an-san. There the negotiations were resumed and when Arriaga heard of these developments he went to mediate between the two sides even though he was not yet fully recovered. Although he could not represent the city of Macau he completed the negotiations to the satisfaction of both sides. He also mentioned the installation of the Bishop of Peking and the return of Macau's lost privileges. He himself will inform Your Excellency of these matters".

The surrender was completed on the 15th of April, 1810 and the signing of the relevant agreement took place five days later on the 20th. Kam-Pau-Sai then told Arriaga that he wished to visit Macau and meet those who defeated him.

On his return to Macau, the population welcomed Arriaga with great joy as the man responsible for the victory. A solemn "Te Deum" was sung in gratitude for the splendid victory of the Portuguese fleet. All night cannon salutes from the fortresses and the tolling of the church bells were heard against the background of the illuminated city.

As a lesson for all, the fourteen villains were beheaded and their skulls were left to rot away on spikes along the isthmus linking Macau to Xiang Shan. The general pardon published in Xiang Shan excluded one hundred and twenty six pirates who were executed, one hundred and fifty one who were exiled for life and sixty who were exiled for two years.

In May news reached Macau than the eighty war junks which had been sent to Fuquien to collect duties were refusing to surrender. The chief of the dissidents was unwilling to carry out the promise which Kam-Pau-Sai had made in the surrender agreement. Kam-Pau-Sai was of the opinion that he should not issue the order a second time and asked the Chinese authorities to provide him with sixty junks crewed by men whom he trusted to go and win the rebels over. He offered his own life and his two sons as hostages as a token of his trustworthiness.

Although Kam-Pau-Sai had until this point acted extremely honourably and sincerely, the Viceroy of Canton did not trust him with the fleet he had requested. Instead he ordered two hundred boats to be prepared, equipped with weapons from Kam-Pau-Sai's fleet and sent them to meet the insurgents. Soon after, this large and bulky fleet had to take refuge in Macau as the pirates had once again defeated them.

News of the defeat reached Canton. Much though his pride had been wounded, the Viceroy sought Arriaga's advice on whether he should accept Kam-Pau-Sai's offer. Arriaga told him that if he were in the Viceroy's position he would not hesitate in making use of the pirate leader without taking his two sons hostage.

The Viceroy delayed his decision no longer. He ordered that Kam-Pau-Sai should be given everything he needed. The new admiral of Canton left everyone in the dark as to how he was intending to proceed. He went to Macau where everything was ready for his reception. On an arranged day the commanders of the Portuguese ships and the most distinguished residents of the city met in Arriaga's house. They hardly had time to greet each other before Kam-Pau-Sai was announced.

Following the complex Chinese style exchange of greetings, Kam-Pau-Sai declared his pleasure at meeting the brave and courageous captains who had defeated him. He asked if the valiant captain of the "Leão Temível" was present. António José Gonçalves Carocha was pointed out to him. Kam-Pau-Sai went up to him and held out his arms as he told Arriaga that this was the man who had done him greater damage than all the Macanese fleet. He added, "I was defeated, but who attempting to fight the Portuguese fleet under your command could be victorious?”.

During his stay in Macau, the courteous manner in which Arriaga treated him pleased Kam-Pau-Sai very much. By the time he left to fight the insurgent fleet he had been deeply moved by their hospitality. He sent a message to the insurgents saying that he was now an admiral of the imperial fleet and sent them the following proclamation:

"Comrades and friends. I know you doubted my order: you did right. You thought of course that it was a trick or that I had been forced to write it. That was not the case. I signed it because I wanted to. If you still have any doubts just listen to my own words. I shall tell you why I surrendered. In this world we can choose between two paths, the good and the evil. All of us want to follow the good path but early mistakes sometimes lead us to the evil one. Formerly I advised you to follow me but I had still not found the good path. Now I know that I was doing evil against the good of the majority.

The Empire has a massive population and our cause serves only a tiny minority. You cannot deny that it is excessive ambition which leads a few to try to take control of what belongs to the majority. It is against the laws of the Empire and against the laws of the gods. We must all work for the greater happiness of mankind. We were doing quite the opposite, destroying that happiness. Now that you have seen the truth I hope you will reconsider and choose the right path. Should you insist on doing otherwise then you shall be on the receiving end of my strength for the first time".

The insurgents, however, refused to accept Kam-Pau-Sai's argument. They reacted with arrogance and scorn and Kam-Pau-Sai was obliged to conquer them by force. In order to show Arriaga and the citizens of Macau that he had not broken his promise, Kam-Pau-Sai brought the captured boats and their crews back to the Territory. The captured boats were in terrible condition and they spent many days in the city being repaired before leaving for Canton.

On his way to Canton, Kam-Pau-Sai was received at Boca do Tigre by countless boats which escorted him triumphantly as far as the port in Canton city. On his arrival he was showered with honours. There was great joy in the city as the people realized they were freed from the terrible pirates for once and for all. The Viceroy enthusiastically recommended the new admiral to the Emperor. The Emperor requested that Kam-Pau-Sai should go to an audience in Peking as he wanted to meet him. There the Emperor gave him an even greater honour by making the former pirate chief a state councillor as a reward not only for keeping his word but also for his knowledge and expertise.

In all the battles against Kam-Pau-Sai the Portuguese fleet suffered only the death of one slave and a few wounded. Nothing could ever compensate them for the tremendous efforts they had made. The Chinese never repaid the remainder of their contribution (they had paid only fifty five thousand of the eighty thousand taels which had been agreed upon). The Chinese also failed to keep their promise to return the former privileges of the city. Macau's huge naval enterprise had been possible only due to the loans granted by the richest traders in the city. These amounted to over four hundred and eighty thousand taels which were never repaid.

Not only did Macau benefit from the destruction of the pirate fleets but also the Chinese and foreigners. The British East Indies Company lost no time in informing its head office that the China seas were now safe and that international trade could now be developed.

In commemoration of the sacrifice and heroism involved in the great victory, Governor Alvarenga proposed that the events should be inscribed in Chinese and Portuguese on two memorial stones which would be put on the Senate building. However, the proposal was quickly forgotten. The city is still indebted to those heroes. António José Gonçalves Carocha has not been commemorated in any way. Only Arriaga had a street named after him at a much later date.

Soon after the victory, the hard-working Captain José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Sousa who led the Macanese fleet so brilliantly was rewarded with the post of Governor and Captain of the Islands of Solor and Timor. As regards António José Gonçalves Carocha, his request "to be granted responsibility for the 'Leão Temível' as she is not being used, together with her cannons and I Shall be in charge of both and will always be at the disposal of Your Excellency" was approved.

Arriaga's triumphant victory was celebrated on the 3rd of June, 1810. On this day the following song, written by the Macanese citizen José Baptista de Miranda e Lima, was performed in praise of his virtues:

Hoped for and dreamed of so often,

Shaded 'neath branches of an olive tree,

Thanks to the bountiful Lord Above,

I return to my beloved city.

Enemy flags shall never again

Be seen on the distant horizons,

Nor shall we hear in surrounding seas

The terrible clamour of cannons.

The cannon balls of death which erstwhile

Caused pain and distress and true horror,

Are loaded today in our cannons

To add to the feasting great splendour.

The name of this Portuguese hero

Is never to fade from our memories.

Let's crown his head with a laurel wreath.

And rejoice in this victory of victories.

Take now this crown from your grateful city,

Though it is hardly an object of laud,

Another one better will rest on your locks,

When you reach Heaven, the Kingdom of God.

For the service which he had done for Macau,

Magistrate Arriaga was given unlimited tenure in

the courts of the Territory until his death at an early

age.

Translated by José Vieira

INSTITUTO CULTURAL DE MACAU

Macau is a work of culture.

The hands of two peoples have raised it. Stone by stone.

Writers, researchers, poets, have built a Memory for it.

They have given it a Soul. Page by page.

The book is exciting. The book continues. In books, Macau lives on.

To publish is to give more soul to the future. Page by page.

REVIEW OF CULTURE No 3-ICM

Price: single copy - 30 Patacas; 500 Escudos; 4 US Dollars

annual subscription-100 Patacas; 2,000 Escudos 13 US Dollars Circulation: 2,000 copies

*Writer, historian, researcher and ethnographer on Macau; sinologist. This text was published by the author in the newspaper "Notícias de Macau" and was included in a later anthology "Páginas da História de Macau".

start p. 119

end p.