The aesthetic characteristics of traditional Chinese painting cannot be discussed without first clarifying the concepts of "form" and "spirit" and "rules" and "ideas" which constitute the two essential and profound polarities in Chinese art. Understanding this is the key to understanding Chinese art.

All nations have their own aesthetic perception, that is, their own criteria for appreciating Beauty. This conditions the search for and the creation of Beauty. Therefore, art must reflect this defined aesthetic concept. It is manifested directly through this concept which is, in turn, enriched and improved through the progress of art, seen in the course of its evolution throughout history.

A rich accumulation of aesthetic principles lies behind traditional Chinese painting. Even before the Qin Dynasty (221-206 B. C.), scholars were writing books with direct and indirect references to paintings. Although fragmentary, these references represent classical, academic thoughts. For example, Confucius proposed that "only finished silken cloth can be used for painting"; Han Feizi maintained that it was "easier to paint spirits than dogs and horses"; Zhuangzi claimed that "taking one's clothes off and sitting with one's legs wide open will make one feel more at ease". These opinions on painting stimulated quality, naturalism and the expression of refined feeling. They had a far-reaching influence and can be considered the first teachings on Chinese art.

"Song of the Clear sky" (detail) in cursive hand by Xu Wei (Ming Dynasty).

"Song of the Clear sky" (detail) in cursive hand by Xu Wei (Ming Dynasty).

From the Qin, Han, Wei and Jin Dynasties to the Tang Dynasty there was a continuous evolution in artistic production. During this time the compilation of texts on art was established. These texts were discussed and analysed, making for a proliferation of works on the aesthetics of painting. Included in these works are: "On Painting"; "A Critique on the Most Famous Paintings of the Wei Dynasty (220-265) and the Jin Dynasty (317-420)"; "Remarks on the Painting of the Mountain Yun Tai" by Gu Kai of the East Jin Dynasty; "Comments on Paintings" by Song Wang Wei of the South Dynasty (420-586); "A Critique on Ancient Chinese Paintings" by Xiehe of the South Qi Dynasty; "Comments on Paintings" by Yan Zong of the Tang Dynasty; "Analysis of the Theories of Painting" by Pei Xaioyuan; "Famous Portraits from the Tang Dynasty" by Zhu Jing Xuan of the mid Tang Dynasty and "Famous Paintings from Previous Dynasties" by Zhang Yen Yuan of the late Tang Dynasty.

From the Sung Dynasty onward, scholars gradually began to produce more and more paintings, emphasizing the harmony between the artistic spirit and the tools of expression. Studying the "form" and "spirit" led to a closer understanding of the mysteries of Nature. Thus flowers, birds, mountains and rivers were increasingly featured in paintings. Consequently the work of the scholars developed in step with that of the Imperial Academy of Art, auguring well for artistic creation. A great number of high quality paintings were produced, some of them of incomparable standard. This artistic explosion automatically stimulated a greater interest in studying the aesthetics of painting.

More than two dozen books were written during that Dynasty, providing a rich accumulation of aesthetic theories on Chinese painting. Some of the most important ones are mentioned here: "A Theoretical Analysis of Painting" by Tong Yu; "Illustrious Portraits of Yi Zhou" by Huan Xufu; "A Catalogue of Well-known Paintings" by Guo Ruoxu; "The History of Painting" by Mi Shi; "Marvels of Nature" by Guo Xi senior and junior and "A Complete Collection of Landscape Paintings" by Zao Han.

This advance in aesthetic notions resulted in a collection of classified theories during the Yang, Ming and Qing Dynasties along with countless numbers of precious works of art. This led Chinese pictorial art to much greater heights. After evolving over thousands of years, Chinese painting was to attain a mature and perfected aesthetic concept with unique characteristics.

In discussing the characteristics of Chinese painting one must concentrate on the following two pairs of relations: "form" and "spirit" and "rules" and "ideas".

"Retreat in Fu Chun Mountain" by Huang Gongwang (Yuan Dynasty).

"Retreat in Fu Chun Mountain" by Huang Gongwang (Yuan Dynasty).

"Form" and "spirit" should, in principle, be in harmony with each other. Many valuable examples of this combination were produced in China. However, there was some difference in opinion as to which was more important. For example, Han Feizi supported the prevalence of "form" in painting. In his story about a dialogue between King Qi and a painter he maintained that it was much easier to paint spirits than dogs and horses as the latter had known forms while the former did not as they had never been seen. Gu Kaizi did not share his opinion. He considered the primary objective of painting to be the expression of "spirit". When he painted Ji Kang's verse "The Flight of the Swan is Seen While Playing Music" he remarked that it was easier to make music than to see a swan in flight.

The disagreement between these two scholars reflects the divergence of artistic tendencies that existed. The Imperial Academy of Art of the Sung Dynasty, which inherited the artistic style of Huang Quan (c. 903-965), favoured faithful reproduction in painting. Once the Emperor Zhao Ji summoned the court artists to paint a peacock taking off in flight. All the paintings showed the bird with its right foot lifted. The emperor criticized them: "You are all mistaken". The artists were flabbergasted, unaware of the reason. The emperor explained: "The peacock lifts its left foot before flying into the sky". This example demonstrates the extent to which the Imperial Academy classified the quality of paintings according to rigid, formal rules.

However, from the moment that scholars started to dominate in painting, the expression of "spirit" became the principle criterion for the appreciation of art. The development of art depends, firstly, on the ability to represent form and only after that can spirit be expressed. The history of art indicates that, in its primitive phase, painting was characterized by the effort to imitate natural forms by "first drawing the outlines and then applying colour".

Before the Tang Dynasty painters had devoted themselves to the search for "form" in an attempt to portray faithfully the appearance of objects and people. The portrayal of "spirit", which functions at a higher artistic level, signifies a great advance on the representation of "form".

During the Tang and Sung Dynasties artists explored further and deeper thus involving a greater and more confident use of "spirit". This was expressed in the works of all the masters of the Yuan Dynasty who gradually freed themselves from the yoke of imitation.

The open, strange, elegant and melancholic landscape paintings of the "Group of Four" (Huang Gongwang, Wu Meng, Ni Zan and Zheu) marked an expansion of innovative trends. Traditional Chinese painting reached its peak during the Ming and Ching Dynasties. Over the centuries the application of outlines and single brushstrokes became accepted artistic techniques which freed the painters from boring imitation and allowed them to express their innermost feelings and emotions.

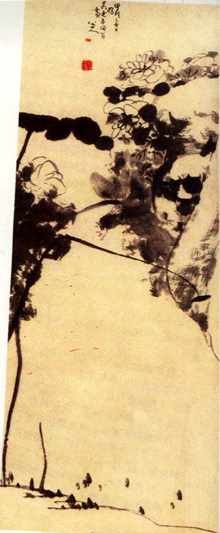

For confirmation of this it is sufficient to contemplate the expressive and rigourous brush and ink paintings of flowers by Xu Wei, or the proud, cold paintings of fish, birds and strange rocks high on barren hills painted by Badashanren.

It should be remembered that the priority given to "spirit" in painting did not exclude attention to formal details. Su Shi‚ a great artist and calligrapher, wrote the following comment on a painting: "Huang Quan painted a bird in flight, its legs and its neck stretched out. It is, however, impossible for a bird to fly like this. Observation confirms that, by scorning detail, he failed to represent reality. This should certainly not happen to any painter, let alone a master! The learned should ask questions in order to learn". The severe stance taken by Su Shi with regard to the combination of "form" and "spirit" forms part of the excellent tradition in Chinese painting.

"Rules" and "ideas", the selection of subjects, laws regarding composition and colour etc. all follow very concrete rules. For example, "generals with short stout necks and women with delicate, small shoulders" dictates the model for the human figure. The proportions should be determined according to the following pattern: the mountains should be largest, then the trees followed by horses and, finally, people. "Yellowish red" was the colour of Autumn, "greenish red", the colour of flowers, "purplish black", the colour of death, "golden pink" for shining objects, ordains the application of colour. "The peak of the greatest mountain should be the highest, the mountains in the background should be lower and the trees nearby should be straight and strong although different in form and size" conditions the composition.

Moreover, the techniques related to the accomplishment of the designs were confined by many rules. Thus, before starting to paint, special attention was to be given to the type of brush and the density of the ink so as to achieve the greatest harmony between the brushstrokes and the quantity of ink used. For example, greater poeticism is achieved when the brush is wetter whereas a drier brush produces a stronger, harsher result. Obtaining certain tones and hues needed to express correctly and suggestively the intended ideas, required a lot of care when dipping the brush in the ink.

"Huangshan Mountain" (detail) by Dao Ji (Qing Dynasty).

Great artists are never governed by rules. Yet, before the brush is applied there must always be a complete and clear conception which govern the rhythm of the brush as it moves over the silk. According to Zhang Yan Yuan in the Tang Dynasty, ideas meant thoughts, feelings, spirit and emotions which predetermine the rules and condition the application of the brush strokes. However, the mere existence of prepared ideas is not enough. The work must be the result of an uninterrupted flow. Lack of concentration results in poor artistic effects of little artistic quality.

There are some who say that the primacy of "ideas" in Chinese painting depends on the uniqueness of its tools. Unlike Western oil painting which can be corrected on canvas as the artist wishes, Chinese artists have to be firm and decisive with their brush strokes while painting because once their work is done there is no opportunity for corrections.

Nevertheless, it should be remembered that the prime objective of Chinese art, just as in lyrical poetry, is the expression of ideas born from feelings. When a painting lacks this spiritual quality it has no potential to move people.

In this article we have discussed the core aesthetic concept in Chinese painting: the representation of "spirit" with "form" and of "ideas" according to "rules". "Spirit", "form", "ideas" and "rules" are the four components that always co-exist in Chinese painting. Harmony between feelings and scenery, the objective and the subjective results in a pattern of aesthetic notions in Chinese painting: the beauty of the single perspective, the beauty of the lines, the beauty of the range of blacks and the beauty of the implicit symbolism.

FOUR ARTISTS BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Huang Gong Wang (1269-1358) of the Yuan Dynasty. His original name was Lou Jen and he came from Changshu. He was adopted by Huang, a ninety-year-old man from Yungja Province and was given the family name. As Huang's first name indicates (Gong means "old man" and Wang means "wish"), the old man had long wished for a son. He was also nicknamed "the absent-minded monk".

Huang was extremely talented in both calligraphy and music. He spent the last years of his life alone, telling fortunes and travelling frequently between Hangzhou and Songjiang.

His works are considered to be simple but profound and full of energy. His most famous painting is "Home in Mount Fu Chun".

Xu Wei (1521-1593) of the Ming Dynasty. Nicknamed "Buddhist Qing Teng", he came from Shaoxing where his studio (Qing Teng Studio) is still preserved. His paintings of mountains, rivers and flowers reflect an artistic freedom and his calligraphy is vigorous and energetic. His works have always been greatly admired.

Towards the end of his life he became mentally unstable and he died at the age of seventy three.

Badashanren (1626-1705?) of the Qing Dynasty. His true name was Zhu Da and he came from Nan Chang in Jiangxi Province. He was a descendant of Zhu Quan, King of the Ning Kingdom during the Ming Dynasty. When the kingdom was destroyed he became a monk. Later he left the order and founded the Qing Yunpu Buddhist Academy in Nan Chang, calling himself "Badashanren". He was an expert in calligraphy and developed his own style. His paintings are much admired, especially those of birds and flowers. They are simple but full of emotion. With a few strokes he managed to convey an intense emotional energy with an undercurrent of bitterness.

Dao Ji (1603-?) of the Qing Dynasty. This was the Buddhist name of Zhu Ruoji, a descendant of a monarch of the Jingjiang reign during the Ming Dynasty. When his father was killed by the King of Tang he felt it was his duty to become a monk and he changed his name to Yuan Ji, cognomen of Shi Tao. He was also known as Old Ching Sang and "bitter cucumber monk". He specialized in poetry and "li shu" (ancient Chinese calligraphy from the Han Dynasty). All of his paintings are very creative and they often include calligraphy. He also wrote some theses on painting.

Translated by Bert Hugh

"Lotus" by Badashanren(Qing Dynasty)

* Art lecturer in the University of Beijing

start p. 67

end p.