The Chinese fishermen of Macau and of southern China in general are one of the most extreme examples of adaptation to the environment to be found in technologically advanced societies. In this article I will present a preliminary study of some of the relations within the triangle habitat-technology-society. From there I shall draw some conclusions about those aspects of the social structure which seem to be more or less conditioned by the environmental factors and technological innovations which have been affecting the fishing industry in recent years. I will also examine an issue discussed previously which dealt with the occasional representation of the fishing community as if it were not really Chinese (Brito Peixoto, 1987). In order to do this we must define what are the basic cultural and social criteria by which a determined group may be described as "Chinese". To finish, I shall consider to what extent the social organization of Macau's fishing community is similar to that of other Chinese fishing communities despite the fact that that of Macau has a specific and unique working environment.

I

The maritime regions of southern China and of Southeast Asia are distinguished by their extensive coastal belt and high density rainfall. They are shaped by a massive labyrinth of lakes, channels and rivers which in turn open out into deltas and estuaries. In these areas in which the gods "forgot to separate land from sea" there have long been communities and cultures which have developed a remarkable degree of ecological and economic adaptation to an aquatic environment. The rugged coastline with its wealth of resources and the rugged topography with the barrenness of the land resulting from high temperatures and heavy rainfall and aggravated by excessive agricultural exploitation of the densely populated alluvial plains may be some of the contributing factors behind this demographic movement towards the sea. Whatever the case may be, the fact remains that the people in this vast area stretching from Southeast Asia through the maritime provinces of southern China to Japan have adapted to life at sea with little difficulty. The Orang Laut of Malaysia and Indonesia, the Mawken of Burma, the Tán-ká and the Hok-lou of southern China and the various ethnic groups from Vietnam, Cambodia and Thailand which have not been categorized: throughout this area there are communities which either live in boats or use them to support water-based life-styles. Floating, in the true sense of the word, these communities have largely been ignored both anthropologically and sociologically with the result that there is an almost complete absence of data on them.

II

Most of the floating population of Canton - and certainly almost all of Macau's fishing community - belongs to the Tan-ka category. Tan-ka is the Cantonese word used to describe them but it has a depreciative connotation and so the fishermen call themselves Soi Seong Ian which means, literally, "people on water". If Tan-ka is to be accepted as a scientific term, as some Chinese writers have used it (cf. Ho, 1965; Chen, 1946), then its use should be limited only to denote that sector of the Chinese population which speaks Cantonese and which lives permanently on boats or which uses them as a means of subsistence. In fact there is a cultural opposition between "boat dwellers" and "land dwellers" which leads to an inherent sociological dismissal of the former by the latter (cf. Brito Peixoto, 1987). The "boat dwellers" resent being at the receiving end of discrimination and contempt while the "land dwellers" claim that they are physically and morally malformed and that their life-style is undesirable, beliefs which stem from the fact that formerly they were prohibited from setting foot on dry land, from marrying "land dwellers" and, as was the case with other minorities, were denied authorization to compete in the Imperial Examinations, a crucial factor affecting social mobility in Ancient China. Usually this is all justified as if the people in question were not in fact Chinese, that is, as if they did not speak Chinese or were not of Han(漢) descent which is what the other Cantonese claim. The fact remains that those who have little contact with "boat dwellers" exhibit an astonishing amount of ignorance about them and the fantastic character of many of their observations can be detected immediately. The problem of origin and disputed tribal roots can, in the absence of any conclusive data, be summarized as follows: it is most probable that the floating population is no more nor any less of Han descent than the rest of the Cantonese in southern China; there have been demographic movements from land to sea and vice versa which suggest that maritime populations are not racially different; the physical features which distinguish, for example, a fisherman (dark skin, a sloping walk, relative muscular hypertrophy in the torso and arms compared to muscular hypotrophy in the legs) can most easily be explained as a feature of the respective adaptation to an aquatic environment (Ward, 1965).

On the other hand it is still true that most of the "boat dwellers" remain illiterate; that marriage with "land dwellers" is unusual (ethnic endogamy) and that when it does occur it is a woman from the sea who marries a man from the land (hypergamy) while the reverse situation is unheard of. It is also true that the group has been the target of prejudices which have been absorbed and now constitute a part of the psychological make-up of the "boat dwellers".

fig. 2-House-boat: a stationary vessel which serves only as a residence.

fig. 2-House-boat: a stationary vessel which serves only as a residence.

III

A brief glance, even with an untrained eye, at the scene in Macau's Inner Harbour is enough to note that Chinese vessels differ markedly in appearance. An observer who is familiar with the maritime situation of southern China can rapidly identify not only the specific purpose of each of these vessels but also the exact region of origin. This is not to say that it is easy to classify them and, in fact, any attempt to do so results in a profusion of mutually contradictory terms. This situation is not wholly unrelated to the statement that "no two boats are exactly alike" (Naval Intelligence Division, 1944, p5). This is because the methods of manual production dictate that, on the one hand, "in a Chinese junk the size and form of the vessel depends largely on the size and shape of the original planks" (idem, p5) and that, on the other hand, the construction is carried out in a craftsman - client context so that specific needs give rise to differences in each vessel. Finally it is worth mentioning that in every yard the only plan which exists is inside the head of each individual craftsman. In addition to the considerable variable of appearance of the vessels there is the factor of different places of origin and regional variations in nomenclature.

The fact is that the maritime occupations undertaken are highly specialized, such as transportation of cargoes and passengers, and fishing, which means that each specific kind of operation requires different vessels and equipment. For the anthropologist it is particularly significant that this specialization not only affects the vessels but also their inhabitants. It is worth remembering that the population sector which continues to live in house-boats which are stationary (cf. fig. 2) or in stilt-houses in sheltered waters close to the bank (cf. fig. 3) constitute quite a different group. This population is often composed of former fishermen who maintain casual links with the "boat dwellers" and share the stigma which is associated with them. They tend to work, however, on land in a variety of occupations thus the water environment is no more than a home and can be seen only as an extension of the land. Sociologically this population is closer to the working classes of the "land dwellers" into which they are becoming increasingly integrated.

Likewise, it should be remembered that only a small percentage of the Tan-ka are involved in fishing. The others are engaged in various forms of transport, either at local level or between the Chinese ports and Hong Kong, and in providing a variety of services within the floating community such as selling water, food and goods (cf. fig. 4). This sector of the floating population which is concentrated around the harbours constitutes the subgroup of the Tan-ka which is most urbanized and similar to the "land dwellers". They have established many diverse links with them because they participate in the social life of the docks while they separate themselves from the the fishing community.

Thus the fishing community is not only defined by its professional specialization but it is also segmented according to the different categories of service which not only condition the style of vessel but also the life of the inhabitants. Thus a Tan-ka born on a trawler will not only spend his whole life exploiting that one maritime resource but will also marry a woman whose family is engaged in the same activity and will bring up his children in the same tradition. Apart from line fishing in shallow waters which is usually practised by all the infant and adolescent fishermen, the maritime resources are exploited according to different fishing skills which are so specialized and require such heavy investment that to transfer from one activity to another was, in the past, extremely unusual. Mechanization in the fishing sector, however, has brought increased social mobility at that level as shall be discussed later.

fig. 3 - Stilt house in Macau's Inner Harbour.

fig. 3 - Stilt house in Macau's Inner Harbour.

IV

Let us now turn our attention to the crew of these boats:

"(...) While on the subject of the crew members of these boats I should point out that the Chinese regard the boat as a permanent home in which the owner's entire family lives. The women display the true qualities of Chinese seafarers, taking on the role of cook for the whole crew. On the larger boats the crew consists exclusively of men. On the "tancar" and "chin-sán t'éang" the crew consists of no more than the family, the owner being, at times, a woman..."

(Barbosa Carmona, 1953 p43)

This pertinent observation, made in the Twenties by Admiral Carmona, at that time an outstanding lieutenant of the Portuguese Navy in Macau, foreshadows the content of this study. The home of the fisherman has, traditionally, been his own boat. Nowadays there is a tendency to establish himself on land. When fishermen use the word "ka" ( 家 ) ("home, family") they are usually referring to the vessel and its occupants. The larger boats often have hired assistants on board but, interestingly enough, they are referred to in family terms as if the crew and the working members, ideally the family, can only be viewed in terms of this structure (1).

Any extensions to the home which has been defined are done according to a common practice: the custom of mooring two boats alongside each other and linking them together (cf. fig. 5). The place chosen to moor the boats is not a mere coincidence. Parents, children and relatives, linked by fishing from the same port, often moor their boats together and join them so that the ties between the boats are translated into both literal and metaphorical family ties. The "territory" of each domestic group is mutually respected and often marked by distinctive decorations such as painting the funnels of the boats in a determined colour or with an emblem. This grouping allows the crews to circulate freely around the decks of all the boats - the men meet to decide on their plans, the women organize meals which bring several families together and the children play together. Thus shelter food and relaxation are all provided within a communal space. There are usually between two to six of these agglomerations to be seen in the Inner Harbour on any day but sometimes there can be as many as twenty during a wedding or on any other festive occasion with a sharp increase during the celebrations of the Lunar New Year. At this time the religious face of the fishing community emerges dramatically: all fishing activities come to a halt and the fleet remains in the port over several days. If all the boats were moored according to the pattern discussed, an aerial photograph taken at this time would reveal the spatial family structure of the community.

fig. 4 - Water seller in the Inner Harbour.

fig. 4 - Water seller in the Inner Harbour.

fig. 5 - Boats moored and linked together.

fig. 5 - Boats moored and linked together.

Let us consider the observations of Admiral Carmona mentioned above. If, in addition to the working members of both sexes, the boats provide a home for children and the elderly then it is plausible that there should be a relation between the kind of fishing being done and the structure of the fisherman's family. Thus the size of the family group is inevitably conditioned by the size of the vessel which, in turn, depends on the economic status of the family and the kind of fishing which is being practised. At this point it is necessary to give a brief description of some technical aspects.

The fishing techniques of southern China are diverse and manifold. For the moment I shall concentrate on some of the most significant ones. I should mention, however, that this is an area in which I am not specialised and I would advise readers who want to gain a deeper understanding to consult specialist literature. Here, a schematic outline will be sufficient.

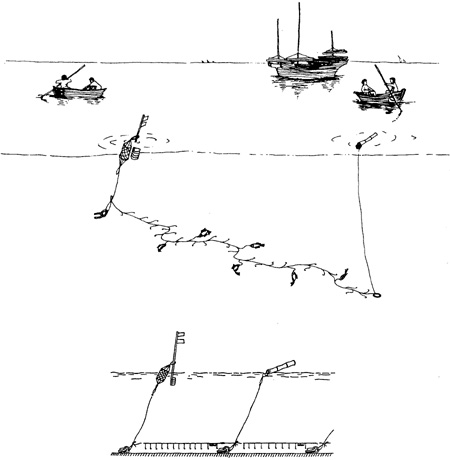

Fishing with weights: a series of lines with weights on the end of them is linked to form a long line spread parallel to the sea bed by means of ballasts and buoys (cf. fig. 6). This method requires a boat which can carry from one to five "sampans" (a kind of boat) and a large crew of experienced, knowledgeable fishermen. The advantage of this method is that the fish can be caught alive, something which is sought after in the marketplace. It fetches a high price and is served as a delicacy in the best restaurants. On the other hand it has the disadvantages of being particularly hard and tiring work as well as being labour intensive both of which pre-suppose a comparatively high financial return. In practice the economic viability of fishing with weights is connected with larger boats capable of transporting an extended family on one boat. This fishing technique is no longer seen in Macau. Part of the reason is that there has been an increase in the emigration of professional fishermen to Hong Kong where their skills bring better returns. Also this speciality is in decline due to the inability to compete with the salaries on land.

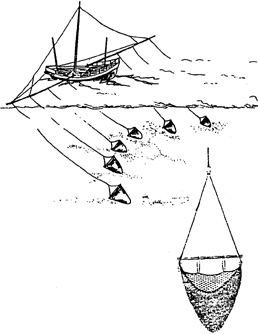

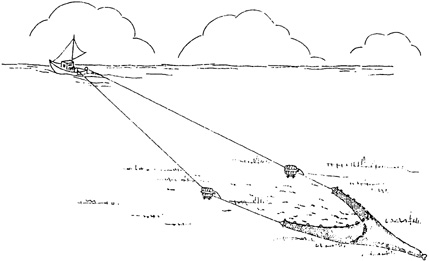

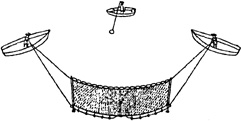

Trawling: the trawler drags a net along the sea bed which collects fish, crustaceans and molluscs. It can be done in partnership, supporting the net between two boats (cf. fig. 7), by the stern, whereby the net is kept open by two supports on each side of the stern (cf. fig. 8) or laterally whereby the net is kept open with poles (cf. fig. 9). The various kinds of trawlers compose the most modernized and most economically significant sector of Macau's and Hong Kong's fishing fleet. It is worth noting that the maritime resources to be exploited are the object of deliberate selection. For instance, fishing with weights concentrates on the nemipterus virgatus species while prawns are the main catch for Macau's fishing fleet, its large majority of lateral trawlers appropriately called shrimpers (ha teng 蝦艇 ) (Serviços de Estatística e Censos 1987). The trawlers have been successively influenced by western technology. There has been a move from the traditional model (with a low stem and high stern, originally intended for use with sails, cf. fig. 10) to a modern model (with a low, free stern adapted for use with an engine and a hoist for bringing in the nets cf. fig. 11). This development has received a considerable amount of encouragement from the government of Hong Kong not only in providing finance but also in producing designs (Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 1996-87). It is particularly relevant to this study to note that the introduction of western style designs, namely those boats destined for high sea fishing, requires sophisticated equipment and heavy economic investment which offer a greater use of space. At the same time they do not allow for the transportation of the family. In these cases the family remains on another boat, anchored in the port for this purpose, or in a room on land. In other words, the introduction of western style technology in trawling is linked to a tendency towards progressive change in the patterns of family life. On traditional boats the tendency is to maintain an extended family.

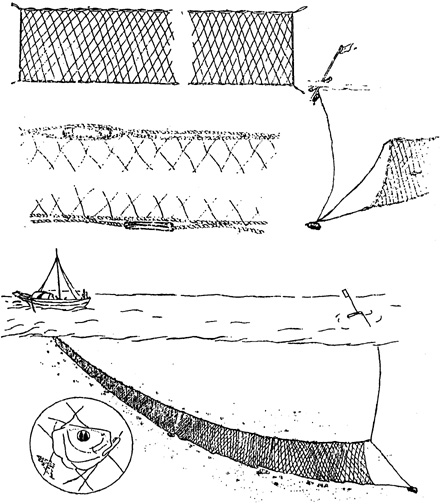

Fishing with nets: this is done by tying fish and crustaceans into the mesh of the net. There are several sizes of net depending on what is to be caught. The rectangular net is held perpendicular to the sea bed by means of ballasts and buoys. One end is tied to the boat while the other end, marked with a flag, is left to drift (cf. fig. 12). This work is done manually in shallow waters working from boats which are usually of traditional design. The boats vary in size but generally there are no paid members on board and the family is the crew.

Fishing with an enclosed net: this requires at least two boats or one boat assisted by a sampan in order to surround the shoal with a net which is then pulled from both sides. The net is held up by means of ballasts and buoys on the surface of the water. Occasionally a third sampan is used to chase the fish towards the net (cf. fig. 13). This work is carried out manually along the coastal waters. The crew consists of the family.

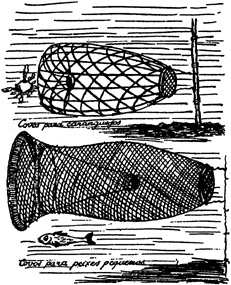

Line fishing in shallow waters and fishing with traps: The traps are made of strong nets suitable for fishing for crustaceans, functioning in a similar way to pots (cf. fig. 14). In common with line fishing in shallow waters, it is done under the constant attention of the fisherman and it can be done by one or two people on board a sampan or other small boat. At an economic level these fishing techniques are of little importance and rather than being a professional speciality they are the recourse of the least favoured sectors of society. Generally, the family has a nuclear composition.

fig. 6 - Fishing with weights.

fig. 6 - Fishing with weights.

It is obvious that there is a close correlation between the size of the family and the kind of fishing which is adopted. Where the crew consists of the family and the boat is adapted to the requirements of the particular fishing technique, more hands are needed on board and we consequently find larger families. Likewise, there is a correlation between the fishing technique and boat size and the family structure: smaller boats tend to have nuclear families while larger ones carry extended families. Also valid is the correlation which is frequently mentioned in other texts on Chinese society: that is the relation between size and the economic level of the family group. We have seen that there are fishing practices such as line fishing in shallow waters and fishing with pots which are dictated by economic necessity. The reverse is also true: economic investment may be dictated by the size of the family. A concrete example can clarify this statement: a former employee of the Government of Hong Kong recorded the case of a fisherman of high repute who rejected an offer from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries to finance the purchase of a larger boat by saying that "there aren't enough people", meaning by "people" that there were not enough people in his own family and that the idea of taking on paid crew members was unacceptable. Hence it is hardly surprising that the Tan-ka value fertility so much. If the domestic group is the unit of production, then larger families, especially with more men, have a more advantageous economic position.

V

Having found a relationship between the family and the crew's size and structure, there remains the question of a possible analogous influence on the kinds of relationships between the group members. In order to work effectively in these boats there must be a clear division of labour. There is a hierarchy of generation, age and sex meaning that power is held by the most senior man in each family. On the one hand, in practice the operation of one of these boats requires an owner who is unquestionably in control particularly in the case of emergencies. In this case, if the family is the crew, then the head of the family is the captain and consequently the traditional authority of the Chinese pater familias (ka cheong 家長 ) is further exacerbated by the functional authority which accompanies his position as owner of the boat. The distance between the "head of the family/captain" and the "family/crew" is very uneven and is displayed in an exaggerated form of authoritarianism in the father-son relationship. The issues of conflict between the father and the elder son and the latent threat presented by the latter towards the former in the Chinese family have already been analysed in other contexts (cf. Wolf, 1970). In the fishing community this situation is exacerbated. Whatever the case may be, there is a natural factor which works against the power acquired by the head of the family - the process of ageing. As time goes on, the balance of power gradually moves from father to son: formally the older man holds authority but, in practice, to the families who live from fishing, authority is usually associated with physical strength. This problem is dealt with particularly early by the Tan-ka. Although there are no available statistics on retirement it is believed that it is unusual to find owners who are older than their mid-fifties. This is justified by the fishing community itself in terms of the fact that their arduous life at sea requires a physically capable owner who does not have to be the oldest man even though that is the ideal. The transfer of power from the father usually to the oldest son amongst the "boat dwellers" takes place earlier than amongst the "land dwellers". This is a gradual process which culminates, probably, in the transfer of the registration license being made out in the son's name. It should be remembered that in Macau fishing boats are not obliged by law to be registered and many are not registered while others have licences from Macau, Hong Kong and the People's Republic of China. Also, in Macau one of the reasons for registering boats is the problem of transference of property.

fig. 7 - Trawling in pairs.

I said that the head of the family is the captain. The reverse situation where the captain easily becomes head of the family is also true. If the work of the family is the work of the crew then to take charge of the crew represents to a large extent an exercise of authority over the family activities. The oldest son may being by taking charge of the family finances and from there make the decision to install engines or to build a new boat while the father, far from the operational centre, gradually becomes relegated to the background while he may still be consulted and be listened to and have the final say on the education of the younger members or on marriage arrangements until he becomes superfluous.

As can be seen, there is a structural contradiction in this system: amongst the "boat dwellers" the traditional authority held by the head of the Chinese family is greater due to the nature of the work which they do but, at the same time, and for the very same reasons, this power is lost at an earlier stage than in Chinese families in other contexts.

VI

The logic of this argument appears to have incurred an apparent contradiction with what Admiral Carmona observed in the comment which was quoted above. This should be clarified. Let us recall his statement that:

"... On the tancar and chin-san t'eang the crew consists of no more than the family, the owner being, at times, a woman..."

(Barbosa Carmona, 1953 p43)

fig. 8 - Lateral trawling.

fig. 9 - Trawling from the stem.

It should be noted that the author elucidates on this statement in a passage in the chapter entitled Local Boats and Traffic where he confirms that the tankar "are used for the transportation of passengers within the port" and that the chin-san-t'eang "ferries between Chin-San and the other river ports nearby" (Barbosa Carmona, 1953 p43). That is to say that the tankar and the chin-san-t'eang, exceptional in that the owner is sometimes a woman, are not fishing boats. At the beginning of this article I separated the fishing community from the rest of the floating population and I have previously reported that "amongst the fishermen it is unusual to find cases where the owner of the boat is a woman for reasons of social order (in obtaining credit) and also for the physical reason that women are not adapted to fishing in open waters (the only exception to this would be line fishing in shallow waters and fishing with pots)". However, it is possible in sheltered waters for women whose husbands work on land or for their unmarried daughters to "organize passenger transportation in small boats by themselves which normally operate in waters sheltered by the port or by the harbo"rs". It was also mentioned that "the latter occupation which corresponds to the view of the harbour which land dwellers most frequently have and which is thus, for them, the most typical, is one of the Tan-ka life-styles which involves a high number of women who own their own boats and thus represent a grave distortion of the traditional role of women in Chinese society" (Brito Peixoto, 1987). Hence it is not entirely surprising that "land dwellers" should accuse the Tan-ka of being a matrilinear society (Ward 1965). It should be pointed out at once, however, that there are no data to support this supposition and, on the contrary, everything points to a strong patrilinear ideology. Thus the nuclear family is composed of a man, a woman and their offspring forming one unit of production, reproduction, food and shelter traditionally on the same boat. Marriages are patrilocal (the woman moves to go to live in the man's boat); women have a lower status than men and sons are valued more than daughters; concubinage is socially acceptable although infrequent due to economic limitations yet divorce and remarriage for widows are the object of social disapproval; inheritance is shared only among the men; when there is an extended family the male lineage is defined in terms of the nuclear family including other relatives whereas the respective women and unmarried daughters are only accepted into the stem family or the joint family. Each boat has an altar to its ancestors (defined, obviously, according to the patrilinear rule) whom they honour during Ching Ming (淸明) (2) and other cyclical festivities. All of these features are to be found in the traditional Chinese family.

In addition to the nuclear family, the Tan-ka include in their extended family groups relationships of up to four or five generations but, unlike other parts of southern China, they do not recognise other groups outside that limit as being of the same clan or of the same lineage. Family lineage as observed by Freedman (1958,1966) in the Provinces of Fuquien and Canton consisted of a group of male descendents with the same ancestor who lived together with their respective wives and unmarried daughters under the leadership of a council of elders who possessed common farming land and were linked by the worship of their ancestors who were "commemorated" in an ancestral pavillion (dzi tong 祠堂 ) where their genealogy was preserved. This form of social organization is still seen in the rural areas of Hong Kong's New Territories (Baker, 1968, 1979). The typical situation in many of the coastal villages near Macau is that of a dualistic community in which the part living on land consists of farmers, very often from the Hakka (客家) ethnic group who share the same surname, and the part living at sea consists of Tan-ka fishermen who have various surnames and have no intermediate form of social organization between the family and the community. The two sectors are linked by a complex system of exchange but they do not intermarry. In other words the Tan-ka do not have clans, nor family lineage nor, as far as is known, did they in the past in spite of the fact that, over centuries, they coexisted with population where these forms of social organization were predominant (Anderson, 1970; Ward, 1955).

fig. 10 - Traditional trawler.

fig. 11 - Modern trawler.

Why do the Tan-ka not have family lineage? Let us rephrase this question by asking under which conditions did family lineage emerge as a form of social organization in southern China. The essence of this relatively complex issue seems to be that in China collective property on land is a conditioning factor in the development of strong family lineage (Potter, 1970). The Tan-ka, by definition a floating population, had no land and their only possessions were their boats which, because of their perishable nature, did not provide a viable basis for establishing any contacts outside the extended family. Following this reasoning it is natural that they sustained themselves through the conservation of their genealogy and worshipping their ancestors was, in broad sense, a ritual sanctioning of the distribution of ancestral property (Potter, 1970). It is therefore no surprise that the Tan-ka keep no written record of their genealogy and do not worship ancestors further back than five generations. The fishermen use wooden statutettes instead of inscriptions on ancestral plaques (san chu pai 神主牌) in order to represent and worship the souls of deceased family members. The population claims that illiteracy is the reason yet there have always been other unfavoured, illiterate sectors of Chinese society who did not have this custom thus it must be due to other reasons. The statuettes are adapted for the purpose of representing five generations after which they are ritually burnt and the ashes thrown into the sea to send the spirits to their final resting place (Anderson, 1970). The "land dwellers" send their ancestral plaques to the temple after five generations have passed where they remain under the care of a priest, or else they send them to an ancestral pavillion where they can be worshipped collectively. Apart from this, in Macau the religious focus of the fishing community is the Templo da Barra (Ma Kok Miu 媽閣廟) where the divine patron of seafarers is venerated. However, this worship is a family affair and does not take on the collective expression of worship of common ancestors which is limited to those who are of the same descent.

fig. 12 - Fishing with nets.

fig. 13 - Fishing with enclosed nets.

fig. 14 - Fishing with pots.

Engravings from Lorchas, Juncos e Outros Barcos Usados no Sul da China by Admiral Artur Leonel Barbosa Carmona.

The Libraries and Documents of Macau.

Another reason for the prominence of family lineage in southern China which has been suggested is the fact that it is a region which was colonized by the Han at a relatively late date. The social organization was structured so as to provide the most efficient protection against hostile peoples as there was rarely any help from the central government (Wiens, 1954). In the case of the Tan-ka, the collective floating population probably profitted from its physical mobility whose flexiblity and independence made it difficult to organize and establish groups which were not part of the family. In addition to this, as I have already mentioned, self-sufficiency is not a characteristic of the fishing communities and in order to survive they had to cooperate with sedentary agricultural communities with whom they built up a dependant relationship. In other words, the other side of their professional specialization seems to be an inevitable complementary social relationship. This explains the importance given to close horizontal relations with elements outside the group even within the fishing community at the cost of distant vertical ties with a common ancestry which are characteristics of family lineage. It is logical that the prevalence of the former type of relation should lead to a dynamic decrease in the latter. With this in mind when discussing the issue of identity in Macau's fishing community I felt the need to discuss the larger issue of ethnic phenomena in southern China. I adopted the controversial approach that many of its characteristics are often assumed to be deeply rooted in the racial or social substrata but do not result from social interaction with other groups. Thus differences between them are, quite rightly, preserved by the positions which each one of them takes in a complementary process of development (Brito Peixoto, 1987). Lastly, it should be recognized that it is not surprising that the fishermen of southern China, with no clans or family lineage, have given rise to doubts about their "Chinese" identity. The occurence of "atrophied lineage" is not entirely unique. It has been discovered in rural communities in Taiwan (Pasternak, 1968) and, as is known, this form of social organization is also evident in Macau, Hong Kong, Singapore and other overseas Chinese communities.

VII

The image I have presented of Chinese society has been based, mostly on studies of a agrarian-based society influenced by a powerful written civilization. Traditional research on China has largely ignored a vast section of the population which, because of its specialized life-style adapted to the water, has encountered problems which other Chinese do not have to confront. Rather than being an exhaustive demonstration of this, this article is intended to illustrate some of the solutions to these problems in the spheres of family and kinship. However, despite the fact that adaptation to the environment conditions relationships of family and kin amongst the Tan-ka, this remains an unmistakably Chinese structure. It is obvious that there are many other levels of social organization of this floating population which it has not been possible to discuss here. However, the analysis of the ecological conditions and the study of the traditional technology provide an empirical base for this to be done.

Translated by João Libano

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, Eugene N.

1970 The Floating World of Castle Peak Bay. Washington D. C.: American Anthropological Association.

Au Lai-shing

1970 "The long-line fisheries of Hong Kong". Hong Kong Fisheries Bulletin, I: 5-18.

1972a "An Inventory of Demersal Fisheries in Hong Kong". Proc. Indo-Pacific Fish. Comm. 13(Ⅲ) 270-297.

1972b "The Status of the Hong Kong Trawling Industry". Proc. Indo-Pacific Fish. Comm. 13(Ⅲ) 262-269.

Baker, Hugh

1968 Sheung Shui, A Chinese Lineage Village. Palo Alto: Standford Univ. Press.

1979 Chinese Family and Kinship. London: MacMillan.

Barbosa Carmona, Artur L.

1953 Lorchas, Juncos e Outros Barcos do Sul da China.

Macau: Imprensa Oficial.

Brito Peixoto, Rui

1987 "Boat People, Land People", Review of Culture No 2, ed.

Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 9-20.

Castello Branco, D. Manuel

1981 Embarcações e Artes de Pesca. Lisboa: Lisnave.

Chen Hsu-ching

1946 Tanka Researches. Canton: Lingnam Univ. Press.

Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Gov. of Hong Kong.

1966 Annual Report. Hong Kong: Government Printer.

Freedman, Maurice

1958 Lineage Organization in Southeastern China. London: The Athlone Press.

1966 Chinese Lineage and Society. London: The Athlone Press.

Ho Ko-en

1965 "A Study of the Boat People". Journal of Oriental Studies. vol 5, no 1-2, pp 1-40

Naval Intelligence Division

1944 The Fishing Craft and Fisheries of Hong Kong. London: Admiralty.

Pasternak, Burton

1968 "Agnatic Atrophy in a Formosan Village". American Anthropologist 70: 1: 93-96.

Potter, Jack M.

1970 "Land and Lineage in Traditional China". In: M. Freedman, ed., Family and Kinship in Chinese Society. Palo Alto: Standford Univ. Press.

Sahlins. Marshall D.

1961 "The Segmentary Lineage, An Organization of Predatory Expansion". American Anthropologist. 63.

Serviços de Estatística e Censos, Gov. de Macau

1987 Inquérito às Embarcações de Pesca. Macau.

Stather, K.

1971 The Evolution of Fishing Craft in Hong Kong - 1947 to 1971. Hong Kong Fisheries Bulletin.

Ward, Barbara E.

Journal of Oriental Studies, n°1, pp 195-214.

1955 “A Hong Kong Fishing Village”.

1965 "Varieties of the Conscious Models: The Fishermen of South China". In: M. Banton, ed., The Relevance of Models for Social Anthropology. London: Tavistock, pp 113-138.

Wiens, Herold Jacob

1954 China's March Toward the Tropics. Hamden: Shoe String Press.

Wolf, Marjery

1970 Child Training and the Chinese Family. In: M. Freedman, ed., Family and Kinship in Chinese Society. Palo Alto: Standford Univ. Press.

AUTHOR'S NOTE

The research behind this article was conducted with a scholarship from the Cultural Institute of Macau to whom I am very grateful. I also extend my thanks to Macau's Marine Services for their logistic assistance and valuable clarification on naval techniques and fishing technology. Any error in the text is the sole responsibilty of the author.

The present article was produced in accordance with conditions stipulated by the ICM and represents the initial stage of a research project on Social and Cultural Anthropology on Macau's fishing community. The brief time in which it was written constituted no more than a pause for reflection during the work at present being undertaken. At the moment I have limited myself to giving an outline of the issues, providing provisional observations. To this end I have written for an informed public although not necessarily specialized in Anthropology or familiar with this particular ethnographical field.

NOTES

(1)These terms, used as a mark of respect, friendship and solidarity, are as follows: "father's eldest brother" ( a pak 阿伯). when speaking to an old man in a position of superiority to the interlocutor, A; "father's eldest brother's wife" (tai sam 大嬸 ) for an old lady in a position of superiority to A; "father's youngest brother" (a sok 阿叔) for an older man or to show deference and respect for someone of the same age; "older brother's wife" (tai sou 大嫂) for a married woman a little older than A; "older sister" (tche tche 姐姐) for a single woman older than A; "younger sister" ( mui mui妹妹) for a single woman younger than A; "older brother" (go go 哥哥 ) for a single man of the same age and to show proximity and solidarity; "younger brother" (tai tai 弟弟) for a man younger than A. This is not a complete list.

(2)Ching Ming ( 淸明 ) literally means "clear and brilliant". It refers to the water in springtime, the period when the Chinese visit their family shrines to carry out traditional rituals which are an important cyclical festivity.

* Dip. in Clinical Psychology (ISPA); Graduate in Ethnological and Anthropological Sciences (ISCSP); M. A. in Social Anthropology (King's College, Cambrigde); Scholarship holder of the ICM.

start p. 8

end p.