To complement the series of exhibitions on the Last One Hundred Years of Portuguese Painting held several months ago, the Leal Senado together with the Luís de Camões Museum produced, in conjunction with the National Art Gallery of China in Beijing, an exhibition dedicated to the ten greatest masters of Chinese Painting of the last one hundred years.

This was the first time that an exhibition of such importance and quality had been produced outside the People's Republic of China. This was thus a great honour for the Leal Senado and the Luís de Camões Museum.

The last one hundred years of Chinese history were marked by the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the Manchus. They were also marked by the establishment of the Republic, by the beginning of reforms in the feudal system and improved contacts with the West and finally, by the establishment of the People's Republic of China.

In the case of Portuguese art, it has been possible to create a series of exhibitions that deal with the different periods of Portuguese Painting in a compartmentalized manner. However, it is not possible to apply the same approach to Chinese Painting because its development has been different.

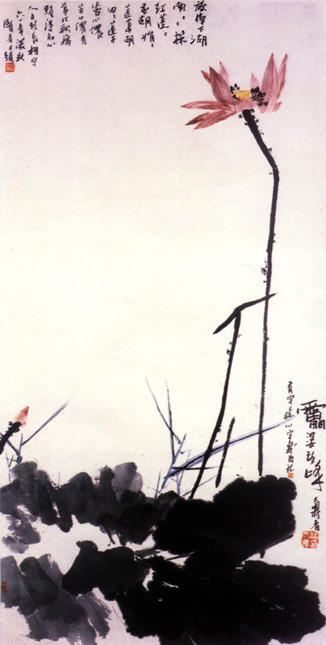

"The Red Lotus", 1961, (138.3cm x 69.1cm)-Pan Tianshou(1897-1979)

"The Red Lotus", 1961, (138.3cm x 69.1cm)-Pan Tianshou(1897-1979)

In fact, the fall of the Manchus and the creation of the Chinese Republic gave rise to winds of reform that also spread to the realm of Fine Arts. More progressive artists criticised the traditional style of painting which involved executing mere copies of the old masters. This naturally suppressed the creativity that was supposed to be part of the new order.

Many of these rebellious artists looked to the Western Academies for new theories and aesthetic formulas that appeared to herald a new wave of Chinese painting.

Therefore the last one hundred years of Chinese painting are marked by a confrontation between the Traditionalist and Reformist Schools of Painting.

However, the issue of reforms in Chinese painting, compared to reforms in the West, dates back to the Han Dynasty (200 BC - 221 AD) when Buddhism was first introduced into China from India. The setting of Buddhist roots in China exerted a deep influence on art and culture. However, as time went by, that philosophy expressed through images and colour was absorbed into the mainstream of Chinese culture and its authenticity and origins were forgotten.

During the reign of the Ming Emperor Wan Li (1573-1620), the Jesuit Mateus Ricci took to China religious paintings that stimulated the interest of some contemporary Chinese artists. Among those who could successfully combine European techniques and style with the Chinese art form, was Ceng Qing from Fujian, who is worth mentioning for starting up a new "Realist School" of drawing.

This style with its followers continued to be popular up to the beginning of the Qing Dynasty and is best seen in the paintings of Man Guoli (1672-1736) and Ding Yuntai who achieved recognition for their works. They were renowned for their portraits and for painting objects in a naturalist style combining both European and Chinese techniques.

"Lotuses in a Vase", 1934(107.5cm x 50.8cm) - Zhang Daquin (1889-1983)

"Lotuses in a Vase", 1934(107.5cm x 50.8cm) - Zhang Daquin (1889-1983)

Up until the end of the Qing Dynasty, however, the impact of European painting was minimal despite the appointment of another Jesuit, Giuseppe Castiglione, as court painter to the Emperor Kangxi. Castiglione was compelled to use traditional Chinese features in his paintings.

Wu Li, one of the greatest Chinese painters at the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, was converted to Catholicism and later became a Jesuit priest. He therefore had a fairly good understanding of European painting. To quote Wu Li:

"Similarity of form is not the objective of my paintings. They are not conditioned by set rules. This is the only way they can transmit the atmosphere I wish to portray. They (European painters) put all their efforts into conventions such as 'chiaroscuro', perspective and imitation".

This formal disapproval of the European style was shared by the vast majority of contemporary artists. Besides this, painting was dominated by most of the orthodox artists who defended the art of copying the great classical masters as the only legitimate way of learning. With the ban on foreign religions declared by the Emperor Qian Long came a rift in cultural relations between China and the West. This cultural relationship was only re-established later on.

But this new surge of interest in European culture was not the result of a merely philosophical interest but was, also, the result of socio-political circumstances in the final period of the Chinese monarchy. The re-introduction of European art at the beginning of the present century was actively supported and sought after by Chinese intellectuals.

The end of the 19th century in China was marked by the growing discredit to the corrupt and inept Qing court that led China into serious decline.

The Chinese patriots tried to save their country by implementing Westernisation and Modernisation on a huge scale. It was thus necessary to create a space in Chinese culture for the introduction of Western science and technology.

The bastion of conservatism was under intense attack from the increasing thirst for knowledge which had spread throughout the entire country, now exposed to the West through numerous open trading ports situated along the China coast.

The rise of pragmatism and the introduction of realism into Chinese painting took place at the same time and was simultaneously made known in numerous essays and articles in the Chinese press. The first illustrated magazines appeared around this time publishing the first widespread illustrations. These conveyed pictorial images to the public that dealt with art forms other than sketches, landscapes, flowers, birds or religious themes.

The functional character of the illustrations and paintings made public by the newspapers, a way of communicating ideas and describing everyday themes, was vital to the receptiveness towards European painting at that time.

In 1905, the Qing Dynasty decreed the abolition of examinations to enter the mandarinate. In their place, state-run schools were created where the curriculum included art courses. In the same year, the great educationalist, Li Duan-qing created a course in art education at Liangjiang University in Nanjing including drawing, carving, water-colour, oil painting, some aspects of Chinese painting such as landscape, flowers and birds, and technical drawing (both two-dimensional and three-dimensional) and graphic design.

The movement of art training, once established, spread rapidly as from 1908, notably in Shanghai where the European presence was particularly strong.

Countless institutions such as the Shanghai School of oil painting and the Shanghai Professional Painting School, the Shanghai University of Fine Art among others became the genuine breeding grounds of new generations of artists.

Chinese art thus entered a new phase of development and at last recognized the presence of European art. Even the Scholars, who had been traditionally conservative, criticised the orthodox schools for their conservatism which had led to the total degeneration of Chinese painting.

"The Sai Leng Pass"(74.4cm x 107.5cm) - Fu Baoshi(1904-1965)

Free expression revealed through painting was ferociously defended by the reformers who hoped to emancipate themselves from their anachronistic past. None the less it was difficult for them to change their deeply rooted habits of copying the old masters.

These reformist artists believed that art had a dual function; to reproduce social reality and to educate the people, incorporating new European-inspired techniques and aesthetic theories.

Among the most zealous reformers, it is worth mentioning Liu Haisu and Gao Jian Fu who was educated in Japan and was one of the founders of the Lingnan School in Guangdong. The majority of art schools placed their emphasis on basic foundation courses, drawing from life and promoting the observation of reality in the place of the old method of copying.

This method of training brought the roots of emancipation from what some considered a disconnected past and allowed countless possibilities for development.

Around the fifties, numerous painters combined traditional techniques in order to paint rural scenes, villages and peasants which formed the base of a social-realist style.

More recently, with the consolidation of social realism, some artists have experimented with abstract painting and new techniques composition using new formulas that have led to a split with the old realism of thousands of years.

In fact it is in Hong Kong that some more active artists, exposed to the permanent influence of the West and the East, led by Lou Shoukun, have been able to make a decisive step to break the last link with the past. One of them, Lui Guosong had an exhibition in Macau at the Leal Senado Gallery in 1985.

The exhibition offered a representative example of the work of ten of the most important Chinese artists, who, through their works, made a major contribution towards the transition from the old Chinese painting to a more contemporary approach.

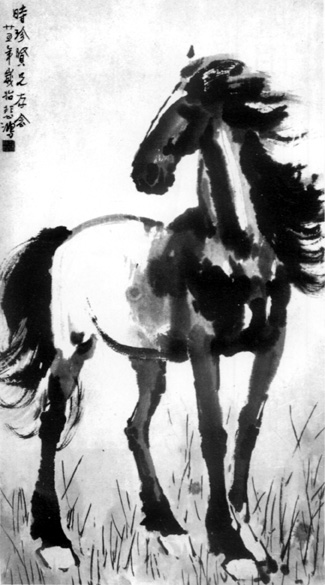

"Horses", 1936(100.2cm x 55cm) - Xu Beihong(1895-1953)

Translated by Daniel Pires

*Director of the Recreational and Cultural Services of the "Leal Senado", Curator of the Luís de Camões Museum.

start p. 63

end p.