FOREWORD

The following summary of the history of Macao is, I suppose, Luís Gonzaga Gomes' last work. It was commissioned to him during Garcia Leandro's government, when there was the intention of including the History of Macao in the High School history programs of the Colony's schools, giving it a special relevance. Shortly after finishing his work, Luís Gomes died, and consequently was not able to give his study the didactic structure of a work meant to be used as a school book.

The work is not divided in chapters nor periods, it has no spaces to give it air and breath, no images to illustrate it. So, in a first approach, it may give a feeling of heaviness. Its reading, however, immediately shatters this first impression, and the way the author regards the historical development of his homeland, giving a special relevance to events and characters which he considered outstanding, may even surprise us. Scholars will, eventually, analyze the rigour of the work or its critical depth; nevertheless, this is a work which increases the richness of regional culture, and it would be a veritable waste to leave it unpublished. Therefore, the Cultural Institute of Macao renders a service which is, beyond any doubt, of great value to the land and city which justifies its existence. In doing so, it also renders homage to someone who was an outstanding figure of Macao; someone who deeply, lovingly and beyond self interest, worked so that his homeland would have its own original cultural expression.

Túlio Tomás

The Portuguese settled in Macao more than four centuries ago. This city, which rapidly grew and developed, remained for a long time the meeting place of two civilizations: Western and Eastern.

Other Western peoples attempted, through other routes and through other latitudes, to establish relationships with the Chinese. However, being extremely jealous of their civilization and culture, which they considered superior to all others, the Chinese refused any contact with the outside world.

From Goa, the Portuguese started a search for new food products and goods. Thus, they tried to establish contacts with the Far Eastern peoples, specially with the Chinese. So, fifteen years after Vasco da Gama's discovery of the sea route to India, Jorge Álvares anchored in the Bay of Tunmen 屯门 (Port.: Tamão, or Guang.: Tâm-Mun), in the Island of Neilingting 內零汀 (Port.: Lin Tin, or Guang: Leng Teng), an isolated island were the ships of Malacca, Manila, Borneo and Luozhou 罗洲 (Port.: Léquias, or Guang.: Loo Choo) Islands were allowed to come.

Jorge Álvares was warmly welcomed and he was followed by other Portuguese merchants. With the mission of opening trade with China, granted to him by King Dom Manuel I [of Portugal], Fernão Peres de Andrade, commanding a fleet of eight vessels, arrived, on the 20th of August 1517, at the Lemtem (Guang.: Lin Tin) Island, which the Portuguese henceforth called Island of Veniaga. Aboard one of the ships was the first Portuguese Ambassador to the Celestial Empire, the Kingdom's chemist Tomé Pires, who in spite of having been received in the Court at Beijing, never met the Zhengde Emperor [r. 1506-† 1521] who had died only three months after his arrival in the Chinese capital. Due to xenophobic conspiracy, Tomé Pires was forced to return to Guangzhou. He died in China, because the condition for his release, and for the release of his attendants, was the restitution of Malacca to the Malays.

Despite this failure, a new Embassy was sent to China in 1521. It was leaded by Martim Afonso de Melo, who had to return to Malacca after his fleet was defeated by the Chinese Navy.

After that, Chinese ports were closed to Portuguese commerce, but eventually the more obstinate Portuguese merchants managed to establish outposts in Ningbo 宁波 (Port.: Liampó, or Guang.: Neng-Po), in the North of China, on the coast of the Province of Zhejiang 浙江 (Guang.: Che Kiang) and in Zhangzhou (Port.: Chincheu, or Guang.: Tcheong Tchau) in the province of Fujian福建(Port.: Fukien, or Guang: Fak Kin). The existence of those settlements was short because the merchants of Guangzhou were more interested in diverting the Portuguese traders to the ports of the Province of Guangdong. Thus, with Leonel de Sousa, in 1553, Portuguese merchants were authorized by the Chinese to settle in Shangchuan 上川岛 (Port.: Sanchoão, or Guang.: Seong-Tch'un) and Langbaiao 浪白滘 (Port.: Lampacao, or Guang: Leng-Pak-Kau), changing soon after to Macao, a small peninsula located to the south of the Island of Xiangshan 香山 (Port.: Tchong-San, or Guang.: Heong San trans.: Perfumed Mountain). The small fishing village, which according to tradition was given to the Portuguese in exchange for the defeat of a famous and powerful pirate called Zhang Xilao 张西老 (Guang.: Tchang Si Lau), was known by the Chinese as Haojing 濠镜(Guang.: Hou Keang, trans.: Mirror of the Well). The Portuguese originally called just 'povoação'('settlement') and, later on, called it 'Cidade do Nome de Deus de Macau'('City of the Holy Name of God of Macao'). The name 'Macao' derives from 'Ma Ou' 妈澳, which is pronounced 'Ma Ao'妈澳 in Mandarin and means 'the Bay of the Goddess Ma'妈澳 or Ni Ma 尼妈 (Guang: Néong-Má)-- the Chinese patron Goddess of sailors and seamen, worshipped in the [Port.:] Templo da Barra (lit.: Mouth of the River Temple).

The date which is generally accepted for the foundation of Macao is the year of 1557, but according to Chinese sources the small cidade (burgh), transformed into a feitoria (factory) by the Portuguese, had already been regularly visited by merchants of that nationality since the year 1535.

We believe that the Lusitan traders organized the first [annual] 'Fair of Macao' in 1558, and, according to tradition, the great national poet Luís de Camões performed the duties of Provedor Mor dos Defuntos e Ausentes (Head Purveyor of the Deceased and the Absent) in this still incipient city.

In the beginning, these traders used to set up their improvised and provisory tents of palm tree leaves or straw each December, but as commerce with the Chinese became more intense due to the fact that they were strictly forbidden to leaving their country, and that the access to the port of Guangzhou was closed to foreign trade, Macao quickly evolved from a simple settlement to an important commercial port, with fine buildings and splendid churches.

One of the most outstanding reasons for the development of Macao was the commerce between the Chinese and Japanese in which the Portuguese played the role of intermediary, since the Chinese could not have any kind of commerce with the Japanese, and these could not touch Chinese soil, for China and Japan were at war with each other as a consequence of the unrestrained pillage by Japanese pirates all along the Chinese coast.

Thus, the Portuguese merchants enjoyed exclusiveness in the acquisition, transport and sale of Chinese silk, which was eagerly sought by the Japanese. The gold and silver obtained from this transaction was then taken to India and China, where there was a great demand for those precious metals. The profits of this commerce -- to which was added the trade of spices and aromatic woods from Indonesia and cloth from India -- were immense.

From 1550 onwards, the commerce with China and Japan became a monopoly, the trading rights of which were granted by the King of Portugal or on his behalf by the Viceroy of [the Portuguese State of] India, to any nobleman who excelled in services to the Crown or to the nation. The title granted was that of 'Capitão-Mor das Viagens da China e do Japão' ('Captain-Major of the Voyages to China and Japan'), or simply 'Capitão-Mor das Viagens do Japão' ('Captain-Major of the Voyages to Japan').The holder of this title had the right to transfer his privileges to someone else.

This Captain-Major was ahead of all the fleets and establecimentos (emporia) from Malacca to Japan, being also the Official Representative of Portugal to the Chinese and Japanese authorities.

Normally, the starting point for these voyages was Goa, with a stop in Malacca, or occasionally in Jakarta -- which was then known as Batavia -- before sailing to the coast of China.

Being the only existing authority, the 'Captain-Major of the Voyage to Japan' was in charge of the affairs of the Portuguese during his stay in Macao, trying as best as he could to maintain order among the turbulent and undisciplined people who were always ready to start bloody fights.

As time went by, some matters appeared which could not wait for the Captain-Major's return from his trips to Japan. Thus, a kind of mercantile republic or free city was formed, whose political matters were then directed by three representatives of the population, chosen by vote, who had the title of 'eleitos' ('elected') and could perform administrative and judicial duties, therefore, what we had in 1560 in Macao was an embryonic municipality.

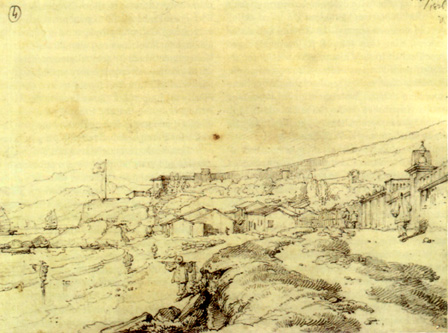

Praia Grande towards Bom Parto Fort.

GEORGE CHINNERY (°London, 1774 - †Macao, 1852).

1826. Pencil on paper. 19.0 cm x 26.1 cm.

Geography Society of Lisbon Collection [no. 4], Lisbon.

Praia Grande towards Bom Parto Fort.

GEORGE CHINNERY (°London, 1774 - †Macao, 1852).

1826. Pencil on paper. 19.0 cm x 26.1 cm.

Geography Society of Lisbon Collection [no. 4], Lisbon.

In 1562, one of the 'eleitos' were chosen to be 'Capitão de Terra' ('Land Captain'). The expenses made with the fairs were covered by a voluntary collection, and there was also a tax on goods coming from [the Portuguese State of] India. Once the expenses were paid, the remaining amount was proportionally returned according to the share each one had contributed to the common treasury, which was called 'caldeirão' ('caldron').

In order to convert the African and Asian peoples, King Dom João III [of Portugal] urged Pope Paul III to send him missionaries of the recently founded Society of Jesus. However, only Fr. Francisco Xavier was sent to India, from there proceeding to Japan, where he achieved astonishing results. Xavier died on the 2nd of December 1552 on the Island of Sangchuan, without fulfilling his desire of missionary work in China.

The Jesuits reached great importance and influence in Macao, frequently interfering in complex administrative problems and quarrelsome political matters, thus saving the fragile existence of Macao in some moments of great danger. Due to the fact that the majority of seafarers and merchants were uncultured people, it was natural that they tried to listen to wiser people, seeking their advise.

Diogo Pereira, who had been sent as Ambassador to obtain the Chinese Emperor's permission for the entry of missionaries, found so many difficulties on the part of the Chinese Authorities that he simply called-off his Embassy. Pereira was able to foresee that the immunity of his position would not be respected, as had happened to the unfortunate Tomé Pires, and decided to stay in Macao where he was elected 'Land Captain'. However, this post was abolished in 1563 because his unofficial election caused deep displeasure at the Royal Court in Lisbon.

Nevertheless, Diogo Pereira did hold the post of 'Land Captain' until 1587, when he unselfishly renounced it in favour of João Pereira, who had arrived from Sunda at the same time as Luís de Melo. Both men had become rich from the commerce of Japan, and both had power to control the inhabitants of Macao. As a result, two parties soon formed, whose rivalry was on the verge of turning into a bloody fight.

Immediately after the city of Guangzhou was besieged by pirates, the Chinese accepted the Portuguese offer of help.

At their own expense, Luís de Melo and Diogo Pereira organized two separate fleets which easily defeated the pirates. In exchange for that help they wanted the Chinese to allow the entrance of the Portuguese Embassy and to grant permission for the exercise of Catholic propaganda in China. And although Fr. Francisco Peres was allowed to work in Guangzhou, where he held religious debates with the Mandarins, nevertheless they replied that it was not usual to allow foreigners to live in China. Finally the Emperor of China wrote to the King of Portugal, saying that the Embassy could not be tolerated due to the fear caused by the disorders which the Portuguese had made in the past years.

Despite the fact that Macao was unconditionally donated to the Portuguese as a gift exempt of any obligation and free from any Chinese jurisdictional influence, the Portuguese soon got used to suborn the Chinese venal Authorities with presents, known as 'sagoates', which soon became an annual obligation called 'foro do chão' (land tax). After the Mandarins' corruption was brought to light, this suborn was officialized as an annual tax of five-hundred taéis, to be paid to the Chinese Government. This continued until 1849, when it was abolished by the Governor José Ferreira do Amaral.

In the year 1565, the Jesuits built the first church. It was a wooden construction, to which was attached a small monastery used as a hospital for the missionaries travelling to Japan. Three years after, in 1568, Bp. Dom Belchior Carneiro arrived in Macao. He was a dynamic man with an entrepreneurial spirit, and in 1569 he founded the Hospital de São Rafael (St. Raphael's Hospital), which included a leprosy hospice, the Santa Casa da Misericórdia (Misericordy) and the Hospital de São Lázaro (St. Lazarus' Hospital) for the Chinese converts.

In 1575, the Diocese of Macao was created, with Leonardo de Sá as its first Bishop. To comply with the Papal Edict of Gregorio XIII, the Igreja de Nossa Senhora da Esperança de S. Lázaro (Church of Our Lady of Hope of St. Lazarus) became the Sé (Cathedral). Due to this fact, the reception ceremony of any newly appointed Bishop takes place there.

The construction of the Convento de São Francisco (St. Francis Convent) dates from 1579,and it is the responsibility of Spanish or Castillian monks. For that reason, it is called Jiasilan 嘉思栏 (Guang.: Ká-si-lan -- the phonetic interpretation of the Port.: castelhano, or trans.: castillian).

With the settlement of the Portuguese in Macao, the Mandarinate spread its authority to the lands surrounding the city and, in 1621, the village of Qianshan 前山 (Guang.: Tchin-Sán), the closest to the northern border of the peninsula, was transformed in a military stronghold, becoming, in 1640, a military post with five hundred men. In 1573 or 1575, with the pretext of stopping the black slave fugitives from entering their territory, the Chinese built a wall on the isthmus, in the place where today we find the Portas do Cerco (Border Gate). In fact, they feared the Portuguese would expand their dominion to the Xiangshan Island nowadays called Zhongshan (Guang.: Tchong-Sán). The wall also had the purpose of fiscalizing the goods which came in and out of the city -- allowing the collection of taxes and the control of the supply flow.

Meanwhile, Spanish religious from the Philippines tried to penetrate China, therefore causing deep concern amongst the Portuguese, both clergymen -- who would have to face unavoidable competition in their work of expansion of Faith and conversion -- and merchants -- who would be powerless to avoid the outbreak of commercial rivalry.

As a consequence, in 1580, the Portuguese made a plight in order to be granted the status of Metropolitan City to Macao, but this demand was not granted.

In 1582, the Viceroy Tchan-Soi of the two Provinces of Guandong and Guangxi 广西, requested the presence, in Zhaoqing 肇庆 (Guang.: Sin Yeng), which was then the Vice-Royal seat of the most important civilian and ecclesiastic authorities of Macao. He alleged that in spite of the donation made by the Emperor of China, the Portuguese did not have Sovereignty Rights over the territory of Macao. Being impossible to avoid such a request, due to the strong pressure of the Chinese, but at the same time being highly suspected, for fear of a trap, to send Dom João de Almeida and Dom Leonardo de Sá Fernandes, it was decided to send in their place the experienced Judge Matias Penela and the Italian Jesuit Michele Ruggieri, taking luxurious gifts which immediately brought down the aggressive arrogance of the Viceroy.

In this way, the status of Macao became clearer, and more stable. Nevertheless, the Viceroy recommended them not to obey the Mandarins' orders, so as to avoid any misunderstanding. **

On the 31 st of May 1582, Fr. Alonso Sanchez arrived in Macao, sent by the Governor of Manila, Dom Gonzalo Ronquillo de Penalosa, to proclaim the acclamation of [King Felipe II of Spain] Filipe I [of Portugal], which was a consequence of the unification of the two Crowns of Portugal and Castille [Spain] in 1580, following the disastrous defeat of Ksar-el-Kebir (Port.: Alcácer-Quibir) where the last King [Dom Sebastião] of the Avis Dynasty died.

Providentially, Fr. Alonzo Sanchez, who, before arriving in Macao, was forced to stay in Guangzhou because of the shipwreck of the ship in which he had sailed from Manila, had written from that city to the Father Visitor of the Society of Jesus, Fr. Alessandro Valignano who was in Macao to accompany the Japanese Ambassadors of the King of Bungo to Pope Xisto V. In this letter, Fr. Valignano was asked to do his utmost to persuade local public opinion to have faith in the Iberian unification and accept the reality of the situation.

The acknowledgment of King Felipe II of Spain as the King of Portugal was celebrated with great caution, for as Macao had been donated to the Portuguese by the Chinese, there were fears that they would react violently.

With the fusion of the two Crowns of Portugal and Castille [sic], the Spanish also started to do commerce in Macao. In this situation, it was easy to foresee a declared hostility on the Chinese part, who wanted to maintain relations solely with the Portuguese. For this reason, Captain-Major Dom João de Almeida wrote a letter of congratulations to the Governor of Manila for the union of the two Crowns, insisting in the fact that no Spanish citizen should be allowed to travel to Macao, and also underlining that the commerce between Manila and Macao should be as far as possible discrete, so as to avoid the aggressive Chinese antagonism. And, to avoid Chinese suspicion, Fr. Alonso Sanchez, instead of returning directly to Manila, sailed first to Japan, and from there embarked for the Philippines.

The Spanish domination was never felt in Macao, nor the Castillian flag ever hoisted, and this happened not as much for political convenience, but because, in the Cortes of Tomar [hist.: assembly of the three estates in 1581, it was unmistakably made clear that all the Portuguese possessions overseas were to keep the national administration and flag.

The official acknowledgment of Felipe II of Spain as King [Fiilipe I] of Portugal took place only on the 18th of December 1582. In order to evade the fact that they had to deal with a foreign authority inside their own country, and also not to loose 'face', the Chinese granted, in 1584, the title of second-class Mandarin to the Procurator of the Senate, who henceforth should be addressed as Yimu 夷目 (Guang.: I-môk, or trans.: Superintendent of Foreigners).

However, despite the promises made at the Cortes de Tomar, as the Castillian and Government of Manila insisted in interfering in the affairs of the Macao Administration, Bp. Dom Leonardo de Sá Fernandes called a General Council of the most important citizens which decided that the city should be ruled by a Senatorial Administration, with a Council called 'Senado da Câmara' ('Senate of the Chamber'), based on the municipal privileges enjoyed by the other metropolitan cities, and which should be composed of three elected vereadores (Aldermen), two juízes ordinários (Judges) and a procurador da cidade (City Procurator).

On the 10th April 1586, the Viceroy of India, Dom Duarte de Meneses, Earl of Tarouca, approved by order of Filipe I the request made in 1580 to his predecessor by the citizens of Macao, being officially recognized the election of the Aldermen, the Judges and the Officers of the Chamber, and therefore, the very existence of the Senado Municipal (Municipal Senate).

The election for the Senate was initially divided in specific areas or departments, and it took place every three years.

All the Portuguese, whether born in Macao or in other Portuguese territories, had the right to vote, as long as they met the legal requirements. The Portuguese born outside Macao were, however, required to be married and living or established in Macao. After the elected were known, their election had to wait for the confirmation of the Viceroy of [the Portuguese State of] India.

The City Procurator was the representative of the Senate in all Chinese affairs, next to the Chinese Authorities of Xiangshan, being also a kind of first instance Judge, for the quarrels between the Portuguese and the Chinese, with the power to sentence in minor cases. The more serious cases, if concerning the Chinese, were sent to the District Mandarin. If concerning the Portuguese, then they were sent to the juiz de direito (Jurisdiction Judge).

When there were serious affairs to be dealt with, a General Council of Ecclesiastic Authorities and high ranking citizens -- most of them former Senators -- was called to decide the measures that should be taken. At the head of these General Councils was the 'Land-Captain' who had the right of casting vote.

With the fusion of the Crowns of Portugal and Castille, the hostility of the enemies of Castille towards the Portuguese overseas territories, namely Macao -- which enjoyed the exclusiveness of the commerce with China and Japan -- became stronger. The unique prosperity of Macao was the target of Dutch covetousness, and several times they tried to conquer the city. The most serious attempt occurred on the 24th of June 1622, when the Dutch managed to disembark on the old Praia de Cacilhas (Cacilhas Beach) -- which today is reclaimed land -- a force of eight-hundred men from the armada of thirteen ships commanded by Cornelis Reijersen, who had under his orders a total of one-thousand-eight-hundred men. A force of about one hundred and fifty Portuguese and mixed-blooded, commanded by António Rodrigues Cavalinho, was the only barrier to the Dutch attack, and, during this action, the Dutch Admiral was shot in the stomach, being forced to abandon the fight and take refuge aboard ship. The loss of forty men during the disembarkation was not enough to discourage the Dutch, who under the leadership of Captain Hans Ruffijn, organized two companies to protect the beach, in the case of a retreat. With six hundred musketeers he went as far as the Monte da Guia (Guia Hill), where a cannon ball, shot by Fr. Giacomo Rho from the Fortaleza de S. Paulo (St. Paul's Fortress) [nowadays called Fortaleza do Monte (Mount Fort)] -- which was not yet finished--, caused the explosion of a gunpowder barrel, with devastating results among the Dutch column, whose soldiers, taken by panic, tried to flee chased by Captain-Major Lopo Sarmento de Carvalho and his men. The two companies at Cacilhas Beach, scared by the desperate attempt to escape of Captain Hans Ruffian's men, ran for the boats, without firing a shot. The day of this spectacular victory was chosen to be the City's Day.

In the year previous to this Dutch invasion -- in October 1621 -- the Chinese requested, by order of the Emperor, the help of one hundred men and artillery to fight the Tartar invaders. Thirty men and four artillery pieces were sent from Macao, arriving in Beijing in May 1622. This small force returned without any loss.

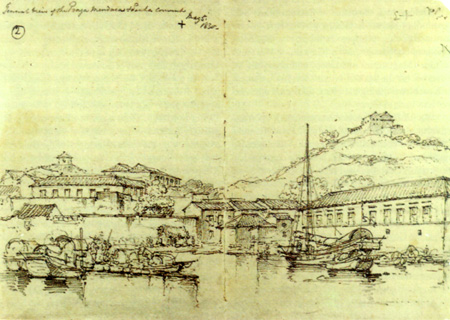

General view of Praya Manduco and Penha command (Praia do Manduco and Penha).

GEORGE CHINNERY (°London, 1774- +Macao, 1852).

1830. Pencil on paper, 18.2 cm x 25.9 cm.

Geography Society of Lisbon Collection [no. 2], Lisbon.

After the unrest caused by the invasion, the citizens of Macao asked for a governador (Governor),and, on the 17th of July 1623, Dom Francisco Mascarenhas took the office of Captain-Major and Governor of Macao. In fact, he was the first Governor since Francisco Lopes Carrasco, who had been appointed capitão de guerra (Captain-of-War) and ouvidor (Magistrate) of Macao, and promoted to Governor on the 28th of November 1615, caused such problems during his office that, soon after, he was sent back to Goa.

As for Dom Francisco Mascarenhas, upon his arrival in Macao, he established the St. Paul's Fortress -- which had been built by the Jesuits -- occupied by a garrison of Castillian soldiers under the command of the Spanish Captain Don Francisco da Silva. Soon after, when the Spaniard returned to Manila with his men, he asked Dom Francisco Mascarenhas to "[...] keep his soldiers both in Mount and Guia fortresses [...]", which in fact happened until the population rose against the Governor. The Fortress' gates were then closed by the priests, to prevent the soldiers from going inside. The Jesuit priests also shot five blasts against the hillock [where the church is] of S. Agostinho (St. Augustin), where Dom Francisco Mascarenhas was at the time. In spite of a Government full of accidents, and faced with the constant opposition of the citizens, Dom Francisco Mascarenhas was able to finish his three years, being afterwards followed by Dom Filipe Lobo, against whom there were quite a number of complaints at the Senate.

Discontented with the arbitrary behaviour of those two Governments, the citizens finally urged the King to abolish the post of Captain-Major and Governor, so that the city could be once again governed by the 'Captain-Major of the Voyages to Japan', this request, however, was not granted.

On the 31st of May 1642 António Fialho Ferreira arrived in Macao, with the news of the success of the 1640 Revolution and the acclamation of King Dom Joäo IV. This news was, at first, received with a certain scepticism, but, a few weeks later, the doubts were cast away and there were huge popular celebrations, which included bullfights, thanks-giving masses, processions, etc..

The city had at that time around forty-thousand inhabitants including refugees from the Civil Wars in China. Of the six hundred Portuguese inhabitants, a great number were new Christians, the Inquisition hardly having been felt because of political reasons and in particular the desire to avoid creating new problems with the Chinese. Macao retained, at that time, a certain level of prosperty having kept the commerce with Manila and other parts of Southeast Asia.

In those days, the population was mainly composed of seafarers and merchants -- men of highly irregular behaviour and undisciplined, who sought shelter in Macao. Thus, without a clear reason, but possibly for lack of payment, there was a military rebellion, with the soldiers taking over the Guia Fortress and pointing its guns at the building of the Senate. Afterwards, the residence of the Governor and Captain-Major, Dom Diogo Coutinho Docem, was attacked and, eventually, he was killed by the soldiers.

Macao was clearly declining. China, after destroying the Ming dynasty [1644], was now raising all possible kinds of obstacles to foreign influence. To worsen the situation of an impoverished Macao, there was a terrible outbreak of plague, which claimed more than seven thousand victims, completely paralyzing commerce. Meanwhile, a man called Zhang Zhilong 张芝龙 (Guang.: Ching Chi Lung) -- who had been a house servant in Macao, under the Christian name of Nicolau Iquão -- became a fearful pirate, with a powerful armada and numerous men. Although he tried to expel the Manchu invaders, these managed to attract him to Beijing with all sorts of promises, where he was imprisoned upon his arrival. Zheng Chenggong 郑成功 (Port.: Koxinga, or Guang.: Chin Chon Kong), his son, swore to avenge him and in 1662 the threat reached such proportions that the Kangxi Emperor [r.1662-†1722] ordered under penalty of death, the evacuation of all the coastal population thirty leagues inland, including the Portuguese of Macao, who were ordered to destroy the fortresses, so they would not fall into the hands of the terrible Zhen Chengkong. However, the Jesuits at the Beijing Imperial Court arranged for the suspension of the Decree in what concerned Macao.

The economic situation of the city became so worrying that in 1660 a huge loan had to be requested from the King of Siam. This was not repaid until 1722.

Meanwhile, the Mandarinate tried to extort as much as possible, to the point of imposing the end of all sea traffic and allowing the opening of the Border Gates only once every fortnight.

To cope with all these difficulties, the Senate requested the Viceroy of [the Portuguese State of] India to send in 1667 a rich Embassy to the Kangxi Emperor. The Embassy was warmly received, and the Ambassador Manuel Saldanha succeded in obtaining a few privileges as well as the recognition of the Portuguese monopoly of the commerce with China, through Guangzhou. Unfortunately, the Macanese did not enjoy this monopoly for long: in 1685 an Imperial Edict was issued, stating that China was now opened to commerce with any foreign nation. The interference of the Mandarins was constant and their demands endless. In 1688 they imposed the establishment of the Hebo 河舶 (Guang.: ho-pu, or trans.: Chinese Customs), under the excuse of avoiding the voyage of the long distance ships all the way to Guangzhou. But of course, the true intention was to have a share in the profits of the Macanese citizens.

Throughout the eighteenth century, the existence of Macao remained a troubled one. There was the usual prepotency of the Chinese Authorities, dissidence among the several religious Orders, misunderstandings between the Governor and the Senate and problems of all sorts.

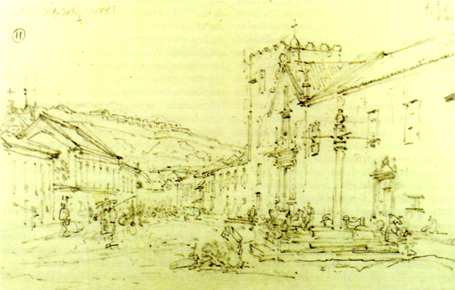

São Francisco Fort with Guia Fort in the distance.

GEORGE CHINNERY (°London, 1774-†Macao. 1852).

1833. Pencil on paper. 17.7 cm x 27.2 cm.

Geography Society of Lisbon Collection [no. 8]. Lisbon.

In 1719, through a Decree of the Emperor Kangxi, Macao became exempt of all tributes. So, in only two years the number of ships grew from eight to twenty-one and, in 1725, the Yongzheng Emperor [r. 1713-†1735] limited the number of ships to twenty-five. This Emperor received, on the 10th of January 1726, the Ambassador Alexandre Metelo de Sousa Menezes, who had been sent by the King Dom Joäo V at the request of the Senate. Menezes demanded the attenuation of the persecution suffered by Christians and missionaries in China. However, the Ambassador was not even able to convince the Chinese Emperor to reduce the severe treatment of the Christian residents of Macao.

There was, then, an upsurge of Chinese oppression against Macao and in 1736 the imposition of native authority. King Dom José I was asked to send a new Ambassador, Dom Francisco Xavier Assis Pacheco. This Ambassador was magnificently received in Beijing at the court of Qianlong Emperor [r.1736-1795] on the 1st of May 1753. However, in spite of five weeks of banquets and parties the Ambassador left the Chinese capital with rich gifts but no positive results.

During the Napoleonic Wars, and as a consequence of an Anglo-Portuguese alliance, the British tried to occupy several Portuguese Colonies, in order to protect them from the French. Thus, with the approval of the Goa Government, the Marquis of Wellesley sent a ship with British troops to Macao, but their services were not accepted by the Governor José Manuel Pinto, who avoided serious problems as a Spanish frigate had just arrived with the news of the Amiens Peace. With the confirmation of this news from Bombay, the only solution for the British was to abandon the waters of Macao.

A second attempt on the part of the British to occupy Macao was in 1808. Magistrate Manuel de Arriaga Brum da Silveira complained to the Prince Regent that two British vessels had invaded Macao, offending Customs Officers and causing serious losses in commerce

Two months after, on the 11th of September 1808, a British fleet, commanded by Admiral Drury, appeared in the waters of Macao, requesting authorization to disembark from the Governor Bernardo Aleixo de Lemos e Faria. The Governor refused the disembarkation of the British forces. But a group of three hundred men attacked and occupied the Fortress of Guia and the Fortaleza do Bomparto (Bomparto Fortress), the remaining British troops occupying the old Seminary, the buildings of the East Indies Company and the tents at Campo da Vitória and several quays. The disturbances caused by the undisciplined British troops, breaking into houses and destroying Chinese graves, provoked a very hostile reaction from the population, mainly the Chinese. With the pretext of protecting himself from a Chinese attack, the Admiral tried to occupy the Mount Fort. After all the concilliatory measures failed, Lemos Faria declined all the responsibilities and Arriaga managed to manouvre the Mandarins in such a way that they strongly opposed the British occupation. The situation became so unbearable to Admiral Drury, that he decided to leave for Guangzhou, in order to get the [Chinese] Viceroy's support for his cause. But, as he was not welcomed he was forced to return to Macao, where the threat of hunger and war forced him once again to leave the city in December 1808, as the Jiaqing Emperor [r. 1796-† 1820] had ordered.

The city had hardly recovered from these incidents with the British, when it was forced to help the Chinese Authorities, threatened by Zhang Baozai 张宝仔 (Guang.: Kam Pau Sai), the chief of the terrible Chinese pirates, who had become extremely powerful and was already a menace to the Chinese [Qing] dynasty itself. Struggling with heavy economic difficulties, the Portuguese negotiator of the joint Luso-Chinese force managed to arm six ships with one hundred and eighteen guns, and equip them with a garrison of seven hundred and thirty men, under the command of Artillery Captain José Pinto Alcoforado de Azevedo e Souza. After several battles near Lantao, the fleet of Zhang Baozai, composed of more than sixteen thousand men and one thousand two hundred guns, was defeated on the 21st of January 1810. However, Zhang Baozai surrendered to Arriaga because he refused to surrender to the Chinese Authorities. As expected, they did not honour the promises made to Macao, and the Jiaqing Emperor, granted the degree of Mandarin to Zhang Baozai, on the 10th of April 1810.

Due to the opposition of the Chinese, Lucas José Alvarenga, was appointed for the second time Governor of Macao in 1814 and was able to assume his position. In fact, he tried to stop the expedition against the pirates of Zhang Baozai and he frustrated the complete capitulation of Zhang Baozai in Macao.

With the proclamation of a Constitutional Government at the metropolis, there were fights between the Constitutionalists and the Conservatives in Macao, the latter being under the leadership of Magistrate Arriaga. Macao demanded the restoration of the old senatorial system, the dissolution of the Prince Regent's batallion -- created in 1820 -- and its substitution by a Municipal Guard, as well as the exemption of having to subsidize the Governments of Goa and Timor. It also wanted all the civilian and military positions to be held by Macanese. On the 15th of February 1822 the new Constitution was acclaimed by the citizens in a meeting in the Chamber, but the adoption of the much wanted reform was postponed, for they still had to wait for the Orders of the King. This delay did not please them and there was a party which maintained that the Constitution should not have been acclaimed in a Government where the official elements of an anti-Contitutional nature were predominant. But, after bitter argument, Arriaga renouced to his duties, in order to be more free to deal with the Chinese. Lieutenant-Colonel Paulo da Silva Barbosa assumed the leadership of the more progressive elements of the Liberal Party, proposing the election of a new Municipality.

Amidst great unrest, the August 19th elections took place, Barbosa voting the prerogatives of the Senate, with legislative, executive and judicial powers. At the time, the Governor of Macao was José Osório de Castro de Albuquerque, who, lacking support, had to submit, Arriaga being arrested for conspiracy and sent to Lisbon to be judged there. Albuquerque did not accept the position of Military Governor which he was offered, preferring to return to the Kingdom. Arriaga, who was supposed to travel with him, managed, at the last minute, to escape to Guangzhou, where he informed the Viceroy as to the events in Macao.

Santa Casa da Misericórdia.

GEORGE CHINNERY (°London. 1774 - †Macao, 1852).

1833. Pencil on paper. 17.8 cm x 27.1 cm.

Geography Society of Lisbon Collection [no. 11]. Lisbon.

To reestablish the former regime in Macao,the Viceroy Dom Manuel da Câmara sent, from Goa, the frigate Salamandra with troops. The Senate gave Barbosa the mission of going to Lisbon to protest against the despotic and arbitrary decision of the Viceroy, but he did not leave Macao, for five days later -- on the 16th of June 1823, the Salamandra arrived in Macao. The Senate advised the ship to leave, and although Barbosa had ordered that in case of disembarkation Mount Fort should open fire, the Commander of the Salamandra decided to send his troops ashore, while in Guangzhou Arriaga convinced the Viceroy of the need to send supplies to the ship. The Viceroy informed the Emperor that Arriaga was an honest man and the sole person capable of re-establishing the order in Macao. Meanwhile, the proclamations of Garcês Palha, Commander of the Salamandra, led the Constitutional Party to abandon the cause of Barbosa, and a new Provisory Government presided by the Bishop of Chacim was formd Arriaga enjoyed further popularity, but soon after he died, at the age of forty-eight. The Salamandra returned to Goa, with Barbosa and his political allies. Garcês Palha returned to Macao in 1825, as Governor.

The fights that occured in Macao further increased the oppression by the Chinese Authorities. In 1829, the White House [i. e., Hebo, or: Chinese Customs] Mandarin prohibited the Chinese merchants from selling copper to the Portuguese. In the following year, the importation of sulphur and salt was also prohibited and, in the same year, the Viceroy of Guangdong decided not to allow any European woman to live in Guangzhou, therefore, they moved to Macao.

Three outstanding foreign personalities lived in Macao in those days: the English painter George Chinnery, who produced a fantastic number of oil paintings and drawings depicting all sorts of views of Macao and its people; the sinologist Robert Morrison, who was the first translator of the Bible into Chinese; and Sir Andrew Ljungstedt, the chief of the Swedish factory and author of a history of Macao. A new colonial regime emerged with the political reforms in the Metropolis and, of course, this had consequences in Macao, where a Royal Decree, in 1835, enforced the new measures. Then, on the 22nd of February 1835, the Senate was dissolved by the Governor Bernardo José Soares Andrea, who was invested with the ample powers of a civilian Governor, the Senate being restricted to Municipal affairs. On the 24th of October 1834 this Governor enforced a decree which abolished the religious orders, although its full execution would only take place in September of the following year. Upon his return to the Metropolis, the Macanese offered him a sword, as a sign of their gratitude. He was so honest that instead of taking a fortune with him, left with only five Patacas, refusing all the comforts which his friends had prepared for his return voyage.

In 1844, Macao was finally liberated from the ruinous custody of Goa, becaming a fully independent province, together with the Islands of Timor and Solor.

The foundation of the British colony of Hong Kong in 1842 and its fast development was one of the reasons for the decadence of Macao.

On April 21st 1846, João Ferreira do Amaral assumed the government of Macao. He was a great administrator, establishing military garrisons in the Islands of Taipa and Coloane to protect the Chinese population against the frequent attacks from pirates. The abolishment of the Hebo and the opening of roads, which forced the removal of Chinese graves, won him a deep antipathy on the Chinese side wich resulted in his murder on the afternoon of the 22nd of August 1849, while riding his horse in the company of his assistant at the isthmus of the Border Gates. As a consequence of his murder, Chinese troops gathered at Passaleão, with the purpose of invading Macao, but the fort was taken by a young Macanese Artillery Tenant, Nicolau Vicente Mesquita, leading twenty-six men with a mortar. After that, the interferences of the Chinese Authorities in the neighbouring district totally ceased in Macao.

After this event, Macao once again enjoyed a certain prosperity, as a consequence of a period of rebellion in the Province of Guangdong, being a city full of wealthy Chinese refugees, who invested their money mainly in the manufacturing and commerce of silk and tea.

On the 13th of August 1862, the Governor Isidoro de Guimarães, got the Chinese to sign a Fifty-Four Article Treaty at Tiajin, in which Macao was recognized as a Portuguese colony but when, in May 1864, the Governor and Minister José Rodrigues Coelho do Amaral arrived in that city to ratify it, there was a bitter argument concerning Article Nine, because the Chinese Delegates considered that Macao could never cease to be Chinese territory and, therefore, Coelho do Amaral returned to Macao, addressing a protest to the Ministers of other powers in Beijing. Only in March 1887, did the Governor and Minister Tomás de Sousa Rosa manage to estabish the Treaty of Friendship and Commerce, the Second Article of which reads: "China confirms, in its totality, the Second Article of the Lisbon Protocol which refers to the perpetual occupation and Government of Macao by Portugal"[…]", the delimitation of borders was left to a future special convention.

In the year 1890 an Agreement was established with China in which the land between the Border Gates and the medium parallel of Aposhi 阿婆石 (Guang.: Apó-Siak) was considered neutral. In 1908 the Naval Officer Diogo de Sá, along with Engineer Miranda Guedes, started the demarcation works, which were not accepted by China which accused them of not being impartial, due to their high positions in Macao. In 1901, José de Azevedo Castelo Branco negotiated a Treaty which was not ratified, since it was disadvantageous for us [the Portuguese]. General Joaquim Machado, assisted by Norton de Matos and Demétrio Cinati, who followed them in 1909, was similarly unlucky. China did not accept the arbitration of The Hague, as it had been proposed.

In 1920 the Government of Macao signed a highly inconvenient Agreement with the Government of Guangzhou concerning the Porto Interior (Inner Harbour). But, in 1922, at the Washington Conference, the Portuguese Delegates, Vicount of Alte and Ernesto de Vasconcelos, almost reached a solution for the problem of delimitation, although it was decided to take the matter to the League of Nations, the final solution being once again postponed regarding what China had agreed upon in the Treaty of 1887.

In 1923, Dr. Rodrigo Rodrigues, who governed Macao, almost saw the delimitation signed by the founder of the Chinese Republic, Dr. Sun Zhongshan 孫中山 (Guang.: Sun Yat Sen), who lived in Macao and worked at the Kiang wu Hospital 鏡湖醫院 (Guang.: Kiang Wu). Unfortunately, the negotiations did not produce the desired results due to the existence of two Governments in China, one in the North, the other in the South.

After the implementation of the Republic, all the governors [of Macao] have made an effort of improving the city in several aspects. With the financial and administrative autonomy reached after the Revolution of April 1974 [in Lisbon], there are good hopes that Macao will enter the era of prosperity, which for so long it has been looking for.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Rui Cascais Parada

CHINESE GLOSSARY

Aposhi 阿婆石

Fujian 福建

Guangdong 广东

Guangxi 广西

Haojing 濠镜

Hebo 河舶

Jiasilan 嘉思栏

Jinghu 镜湖医院

Lanbaijiao 浪白滘

Luozhou 罗洲

Ma Ao 妈澳

Neilingting 內零汀

Ni Ma 尼妈

Ningbo 宁波

Qianshan 前山

Shangchuandao 上川島

Sun Zhongshan 孙中山

Tunmen 屯门

Xiangshan 香山

Yimu 夷目

Zhang Baozai 张宝仔

Zhang Xilao 张西老

Zhaoqing 肇庆

Zhejiang 浙江

Zheng Chenggong 郑成功

Zhang Zhilong 张芝龙

**T'IEN Tse Chang, Sino-Portuguese trade from 1514 to 1644, p.99 -- "This dramatic scene, disgraceful as it was to the Chinese Mandarinate, gave the Portuguese colony at Macao a legal status [...]."

* Historian and researcher on the History of Macao. Author of numerous articles and publications on related topics. Sinologist.

start p. 131

end p.