"Querem alguns que seja palavra Arabica. Em Castelhano, Naipes vai o mesmo que Cartas de Jugar; dizem que se chamão assim da primeira cifra que tiverão, na qual se encerravam o nome do inventor: era hum N, hum P, que significava Nicolau Pepin. [...] Entre nós Naipe, he o metal ou a cor das cartas [...]."

("Some are of the opinion that is an Arabic word. In Castilian, Naipes (Suits) stands for Cartas de Jugar (Playing Cards); and some say that they are so called because when they were printed for the first time they displayed the name of their inventor: an N and a P, meaning Nicolas Pepin. [...] Amongst us Naipe (Suit), stands for the pip or the colour of the cards [...].").

Don Raphael Bluteau, Voccabulario

Portuguez-Latino, 1716

§ 1. THE CONQUIM, THE MANILHA, AND THE SOLO OF MACAO

According to what the majority of historians admit today, the Saracens were the ones to bring from the Orient, in the seventh and eighth centuries, the suits of cards which would soon conquer Europe and be integrated in the cultural complexes of the various groups which came to occupy the countries known to us today. It is highly likely that the Iberian Peninsula was the gateway of these games to the Occident.

Bullet (1757)1 and Rives(1780), 2 for instance, say that"[...] the origin of European card games can be traced to Spain, which received them through the Moors from the Orient, and from India." Some researchers base this hypothesis on the fact that the oldest, or one of the oldest, Iberian card games, known as 'D'el hombre', can be compared with the Indian game of 'Ganjiva'.3 However, other authors, as for example Stewart Cullins, 4 consider that the cradle of game cards is in China, and that the Indian game is of European origin, having been taken from the Occident to India, after being re-created from Chinese cards.

This possibility has been highly contested due to the lack of documents on the subject. But the truth is that only in a time where the existence of social unrest, resulting from the passion for gambling, began to take place, did the Authorities take the matter in hand, thus producing the first registers in the form of prohibitions or condemning laws.

According to Salvini, 5 it is very likely that chess games, as well as card games, were introduced in Europe at the same time, following the Moorish tide of invasions.

Once in Spain, in 710AD, the Arabs continued their march towards France, managing to penetrate into Languedoc. Inspite of having been repelled at Poitiers, they settled in the South of Spain until 1492. Perhaps for this reason, many authors admit that the Moors were the ones to have introduced the game called 'Hombre' ('Man'), an ancient Spanish card game similar in many aspects to the Indian game 'Gangiva' ,6 which resulted in the famous French 'Quadrille'. Like this one, other forms of playing were, probably, introduced by the Arabs and Berbers during their occupation. Which of these forms survived? And under which forms?

According to coeval documents, the use of the game of naipes (suits) in Italy goes back to the end of the thirteenth century, and it was dated, in the rest of Europe, to the first half of the fourteenth century. Thence, some authors attribute to the Italian Peninsula, and not the Iberian, the European focus of irradiation of card games. 7

In his Istoria della Citta di Viterbo, Covelluzo already mentions the use of numbered cards, instead of figurative ones, in Italy in 1379.

He writes: "In this year of great unrest a card game known as 'Naib' was introduced in Viterbo by the Saracens."8 However, one should note that the Hebrew word for witchcraft is 'naibi' (a word which to may have given the Iberian term 'naipes') and that the first cards known in Europe are figurative, of the 'Tarot' kind used by gypsies for divination, a fact that apparently points to diverse sources and epochs of introduction.

In a register of Payments of the Accounts Chamber of the King Charles VI of France, dated 1392, it is stated that the painter Jacquemin Guigonneur painted three sets of card games "in gold" and several colours and symbols for that monarch, of which a few cards are kept at the Bibliothéque Nationale (National Library), in Paris.

These cards, among the oldest known in Europe, were of the 'Tarot' kind, and it is likely that being the gypsies fortunetellers, they brought them from the Orient through Persia, Arabia and/ or Egypt to Italy, from where they were introduced into Europe. However, it seems possible to refute this theory for in France, in Flanders, in the Lower Countries, in Germany and Italy, card games were already known before 1350, while the greatest known European gypsy immigration is posterior, dating back to the fifteenth century.

Nevertheless, we should not reject the possibility that through the Silk Road the numbered cards of the Orient reached the Near-East and afterwards Europe, via different routes and different periods of time. Not only merchants but also the Crusaders, 9 or even sailors, could have been vehicles of transmission. Italy still claims for itself the introduction of card games in Europe through the port of Venice, which had already been frequented for many years by a great number of Oriental seafarers. But what kind of card games were those?

In the middle of the fifteenth century in Catalonia, two kinds of suits were known: 'Moorish suits' and 'plain suits'. Would these correspond, respectively, to 'numbered card decks' and 'figurative decks', or to 'tarot decks'? 10 The question of which of these two kinds of decks conquered Europe first is still opened.

In Spain, there are several legends relative to the invention of card games.

According to one of them, registered by Francisco de Luque Fajardo, 11 the inventor of the naipes (suits) was from Madrid, known as Villán or Villa, 12 who ended up in the fire for the crime of coining fake money. This more or less legendary figure was so popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that sometimes it was evoked with swearing and blasphemy by Iberian players as their 'protective deity'.

It is possible to believe that suits were already known before the fourteenth century in the Iberian Peninsula, through Moorish introduction, but the truth is that they are not mentioned either in the Libro de los juegos (Book of the Games) of Alfonso el Sabio (the Sag), nor on the Ordenamiento primero que hizo el rey don Alfonso em razon de las tafurerias en la era de mil tresientos e quarenta annos (The first Ordinance made by King Don Afonso because of the [?] on the year of one-thousand-three-hundred-and-forty). They are only mentioned on the Ordenanzas de la Orden de la Banda (Ordnances of the Order of the Banda), in 1332, imposed by Alfonso of Castille, and through which "[...] Knights were forbidden to play suits."

Also in the fourteenth century Portuguese Ordenações Afonsinas (Afonsine Ordnances) 13 [1521], where the Laws of the former reigns were compiled, dice games and other games which are not described were forbidden, but no card games or suits are mentioned.

In the Ordenações Filipinas (Philippine Ordinances)14 [1595-1603], later ratified by King Dom João IV, it was also forbidden, in the beginning, "[...] for anyone of any condition to play, keep at home or carry cards, to manufacture them, import or sell them." This prohibition of card games was later abolished through th Royal Decree of the 17th March 1605. Similarly, in Castille, the game was finally authorized, while cards were included in the Royal Monopoly.

Dice games, however, remained forbidden by the Decrees of the 24th March 1656 and the 28th October 1696. The penalties incurred for infraction included, besides a fine of forty cruzados, a year of exile in Africa.

Before the existence of these prohibitions, it is a known fact that the garitos (gambling houses) paid high sums to the King. Apparently, gambling was a right of lordship until the reign of Dom Afonso IV, who prohibited games and the already vicious practice of gambling. At that time the most widespread form of gambling was the dice game.

In Portugal the playing of dice and cards is, nevertheless, a very ancient practice. Gil Vicente (ca1465-ca1537), on his Auto dos Físicos (Auto of the Physicians) mentions that Master Fernão cultivated them, although physicians were not allowed to amuse themselves with games of fortune, whether cards, dice or other similar games.

Through this document one may conclude that in the Iberian Peninsula, even after the Moorish invaders' retreat, the passion for card games lasted through the centuries, in spite of the several prohibitions and threats, on the part of both civilian and Ecclesiastic Authorities, to which were submitted those who played them, as a consequence of the excesses to which gambling lead.

According to several voyage accounts, we know that during the expansion period, Portuguese and Spanish carried with them dice and cards, in their more or less light luggage, in order to while away the long hours spent at sea. Many times prohibited and condemned by the Church, it is common knowledge that inspite of being considered an "[...] invention of the Devil [...]", 15 these games always managed to resist all condemnations, defying even Eternal Damnation.

Therefore, it is not surprising that on the occasion of storms at sea, and with this risk of loss to the ship, the sinful decks of cards were thrown over the side while kneeling and begging for Divine pardon, as some religious described in their journals and letters sent to the respective Orders. 16

What is sure is that wherever the Portuguese and the Spanish arrived, card games ensued, and with them the traditional Iberian passion for gambling. 17

As examples of this dissemination we may point out the 'Conquien', which was found among the South American Indians and which we have found in Macao, still present in the memories of our older informers of the sixties and seventies, under the designation of 'Conquim', together with other games, like the 'Manila' and the 'Solo', which are locally considered to be of very ancient origin, keeping trace rules of the old Iberian game of 'Homem'.

To reinforce this thesis, there are very curious accounts which resulted from the meeting of cultures, such as, for instance, the existence of Japanese decks of cards with rules unknown to the Portuguese, used as a substract of Western type cards, with symbols roughly painted immediately before use. 18

Today, the existence of Iberian decks older than 1600 is unknown, but there is no question as to their existence before that date, as we have demonstrated above.

This fact is further reinforced by the affirmation of Henry René d' Allemagne19, an authority on French card games, according to whom these games must have entered France from Spain, brought by the Knights of Du Guesclin, when they went to the Peninsula around 1367, to fight against King Dom Pedro I O Cruel (the Cruel) [°1320, r.1357, †1367], of Portugal.

Whatever the history of the introduction of game cards in the Iberian Peninsula, the fact is that, circa 1540, the Flemish author Pascasius Justus — who travelled in Spain and wrote a small book of memoirs — registered the "[...] Iberians passion for card games."

In addition, since the fifteenth century the cities of Toulouse, Thiers and specially Rouen, exported game cards to Portugal and Spain, carried on board the busiest commercial ships. The demand was surely great, for they were also produced in Portugal at that time, at the workshop of Inferrera21. Those cards, contemporary of the French ones, were printed by means of wooden blocks, in orange and black, the paper being similar to that used in the cards of Limoges. 22

On those cards, of which a few remain at the London Museum, in London, and at the Bibliothéque Nationale, in Paris, the 'Aces' were represented by a big "A" in the centre, while the 'marks' were depicted in the mouth of dragons. One should note that in the decks of the ancient game of 'Homem', which spread from Spain to Europe, there was no 'Queen', in compliance with the Oriental custom. In its place there was a 'Knight' or 'Jack'. It was a game for three persons, thence the appearance, at the time, of special triangular tables, such was its popularity. Is it possible to think that the expansion phenomenon was responsible for the popularity of card games?

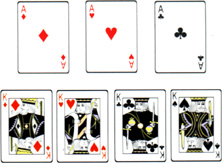

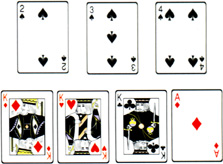

The 'Peninsular cards', forty-eight in each deck, were marked according to four series of suits: 23 'Cups' (Port. and Castill.: 'copas'),'Spades' (Port.: 'espadas'), 'Coins' (Port.: 'oiros'), and 'Clubs' (Port.: 'paus', or Castill.: 'mocas' or 'bastões'). 24With the spreading of the different kinds of European decks, depicting the greatest variety of symbols, the modern and universal 'Diamonds' ['Coins'] (◆),'Clubs' ['Clubs'] ( ), 'Hearts' [ 'Cups'] (

), 'Hearts' [ 'Cups'] ( ), and 'Spades' ['Spades'] (

), and 'Spades' ['Spades'] ( ), lost all and any connection to its initial figurative representation.

), lost all and any connection to its initial figurative representation.

The truth is that when comparing the different symbols depicted on the first known cards, in Europe, to the Chinese and Indian cards widespread in Persia and, probably, all over the Middle East, we are lead to defend its introduction through that way and not through a direct Far Eastern itinerary.

Of the comparison between the symbols of Indian cards, representing the figurations of the 'ten avatars of Vishnu'; with the European symbols, we find in fact, motives which could have given 'lily flowers' or 'acorns', suggesting 'Coins' ['Diamonds']; 'snakes', which might have suggested 'Clubs'; symbols suggesting ball-bells or others still, like the 'bows and arrows of Rama Chandra', suggesting 'Cups' ['Hearts']; 25 and finally the true 'swords' or 'Spades'. Likewise, we may admit that the 'flame', a symbol of vital force, was the source of inspiration for the stylized 'leaves' which resulted in the symbol which, later on, replaced the 'Spades' but kept its name.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the unification of symbols seems to be already an accomplished fact in Europe. The initial difference was probably a result of the several interpretations of the Hindu, Persian or even Chinese motives of the original cards,

§2. ANCIENT EUROPEAN CARD GAMES IN MACAO

Nowadays, it is commonplace to link the idea of gambling to Macao, an historical fatality which resulted, in the early times, from the way it was populated, as well as from the great political and administrative autonomy which the territory enjoyed. Later, when the Portuguese were expelled from Japan, and commerce was not enough to cover the City's expenses, it became a form of economic survival.

Once fortune games were forbidden in Guangdong, the more or less clandestine, more or less visible, fever for gambling transferred to Macao some of the favorite games of the Chinese, and in the last century the city was already known as the 'Monte Carlo of the Orient', "L 'enfer du Jeu", and other similar names.

Through a Decree dated to the 27th October 1877, the establishment of 'Fantan'26'Azar' (lit.: bad luck) and 'Carteado' (lit.: card dealing) gambling houses in Macao was declared free, subject only to the payment of a license. Thus, gambling became one of the city's official sources of revenue.

This form of entertainment, which today is one of the touristic elements of Macao, was already established, even before its liberalization, as one of the characteristics of the territory, at least since the seventeenth century, when Jean-Baptiste Tavernier visited the Orient. 27

On the account of his third voyage, this author tells us the story of the gentleman Monsieur Du Belloy, a lover of gambling and pleasure:

"Du Belloy souhaite qu' on le laissât aller à Macao, ce que luy fut accordé. Il avoit appris qu' une partie de la noblesse se retiroit en ce lieu-lá aprés avoir beaucoup gaigné au négoce qu'elle recevoit assez bien les étrangers, qu' elle aimoit fort le jeu, ce qui estoit la plus forte passion de du Belloy." This Frenchman of good lineage, was, by the way, granted the satisfaction of his pretension because of a distinguished career in arms at the service of the Portuguese. Unfortunately he ended up being arrested in Macao and sent to Goa to be present before the Tribunal of the Holy Inquisition for having cursed a religious image, blaming it for his ill luck whenever he lost. In fact, his bad luck turned to good, for he managed to escape during the voyage.

Giving credit to this description of Macao, as a land of gambling and pleasure, and pointing to card games as one of those practiced there, we found, in the Biblioteca da Academia de Ciências (Library of the Academy of Sciences) in Lisbon, a seventeenth century manuscript which prohibited the use of cards depicting ecclesiastic symbols, of the same kind as those in use in that city at the time. 28

What kind of card games where then played in Macao?

We could not find any written elements that allow us to reconstitute neither the rules, nor the names of those games.

However, using the collective memory of the Portuguese of Macao, and analyzing the card games' rules which were played there during the sixties and seventies — or those which the older citizens could still recall — we found three games that by comparison to the more remote ones which were described for the Iberian Peninsula, seem to point, at least, to a rather ancient introduction on that territory.

These three games, almost completely abandoned by the beginning of the twentieth century — replaced by 'Poker', 'Bridge' and 'Canasta' — were known by the names of 'Manilha', 'Conquim', and 'Solo'.

Before making a brief description of the rules of these three Iberian games of Macao, we think it may be interesting to register the names given locally to the four suits:

'Diamonds' ['Coins'] (◆) = (Port.: quadrados, or lit.: squares).

'Clubs' ['Clubs'] ( ) = (Port.: flores, or lit.: flowers).

) = (Port.: flores, or lit.: flowers).

'Hearts' [ 'Cups'] ( ) = (Port.: corações vermelhos, or lit.: red hearts).

) = (Port.: corações vermelhos, or lit.: red hearts).

'Spades' ['Spades'] ( ) = (Port.: corações pretos, or lit.: black hearts).

) = (Port.: corações pretos, or lit.: black hearts).

These names which survived in the local dialect seem to point to a big difference in the names by which the four suits of cards were known in Macao, which is not strange, since there was no uniformity to designate them in Europe and because the gamblers who in that city of the Orient who gave themselves, since the earliest times, to the passion of gambling came from a great variety of nations.

Next, we shall describe the rules of those three oldest games we found in Macao, comparing them to the Iberian versions.

§3. THE 'MANILHA'

In Macao, in the local colourful dialect the Western cards were, and are still, known by 'cartas manila' or 'cartas manilha', in opposition to the more widespread Chinese cards, called 'cartas-chinas'.

Some informers believe that this name,'cartas manila' or plainly, 'manilha', is due to the fact that they were introduced via the Philippines, a theory we do not subscribe to because our sailors already knew and used these cards in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

Even if we would accept the possibility that the vulgarization of card games happened later, it would be more likely that it would have been made via the Kingdom of Portugal-Goa-Macao and via Spanish influence through the Philippines, although that route was used indirectly, by way of Japan, for commercial trade.

It is our belief that the name 'cartas manilha', 29 corresponds to the more common form of playing, that followed its introduction or that, afterwards, became more popular in Macao, i. e., to the Chinese way of naming card decks. Following this theory, we searched, among the Macanese and among the Christian population of Mallaca, a game called 'Manilha', and we found it. Although greatly forgotten by the majority of the informers, it was finally described and demonstrated. We were told that in former times it used to be very popular among the local Portuguese.

The 'cartas manilha' of Macao are, as mentioned before, the common Western cards which conquered the Iberian Peninsula, and are today reproduced according to a French model of the nineteenth century.

One should note that the Spanish word 'naipes' (suits) used to designate card games, was also used by the Portuguese and in Macao for the 'cartas-manilha'. Such a fact could lead to re-thinking its possible introduction via the Philippines, but the truth is that 'naipes' is an ancient term, common to both Portuguese and Castillian, and possibly it was the word used in the Kingdom of Portugal, when game cards where taken to Macao. Moreover, such a name was afterwards replaced there by the word 'cartas' (i. e., 'cartas chinas', 'cartas de bafá', 'cartas de pau', and 'cartas manilha').

The 'Manilha' is in fact a very ancient game and it seems that it was introduced in Portugal via Spain. Therefore, we should not reject that it was taken to Macao via the Philippines, thence the local confusion concerning the name 'Manilha' or 'Manila' and the extension to the very source of introduction of the card games.

In Macao, the 'Manilha' had already by the sixties and seventies lost part of its former popularity, although it was still possible to find many people, aged forty to fifty, who knew its rules. In Malacca, the game of 'Manila' has also survived, as a Portuguese tradition, among the Christian population which, like in Macao gives to the Western cards the name of 'cartas manila'.30

Let us then compare the rules of the 'Manilha' in Macao with the ones used in Portugal under the name of 'Brinca' (lit.: play), still in the beginning of this century.

Number of players = Four, in two teams of two partners.

Finality of the game = To get the 'Aces' and score the greatest possible number of points.

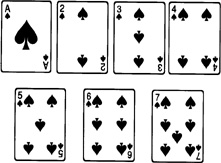

Rules of the game = First, all the 'tens' are excluded from the deck because card 'nine' — the 'manilha' — is the highest. Following this, one of the players shuffles the deck and the person seated to his left breaks the cards.

The player who shuffled the cards starts to deal them, by the right, four by four, to each player, until everyone gets twelve cards. The player who shuffled and dealt the cards is the first to play.

Generally, the games are played between partners: two against two. Partners should sit facing each other, for by slight movements of the face and eyes they may exchange precious information about the respective games, although this is considered somewhat unfair.

The strongest card is the 'nine'— the 'manilha' — from which the name derives. It is followed by the 'Ace', the 'King', the 'Jack' and the 'Queen'.

The last card of the deck has an open value and it constitutes the trump. It belongs to the first player, who will be the first to throw a card on the table.

Rounds are played one after the other. Each player must follow the suit and to cover the card played by his predecessor. If the player does not have a card big enough for that, the player may play a lesser card or 'cut' with a trump.

If a player is particularly favored by luck, holding a great number of trumps, he may use them to draw out the adversaries' trumps, forcing them to cover, or to follow, the cards of the suit that was played (from the lesser to the highest card, of course). Locally this called to 'desdentar as pessoas' (lit.: 'break the teeth') of the adversary.

As we have said, each player is forced to cover the game of his predecessor, he must only follow the suit. If the round is won by his partner, and as in any game based on point counting, it is convenient to play the 'Ace' or the highest card one is holding. In this case, it is not necessary to 'cut' the game because the cards that are won by one's partner all go to the same pile.

The fundamental difference between the 'Manilha' and the local 'Bisca' (Pop.: catch) is, according to our informers, 31 in the fact that one is not forced to follow the suit or cover the predecessor's game. The contrary of 'Manilha', in which these are almost the sole rules. Another difference consists in the number of cards distributed to each player, 32 which in the 'Bisca' may vary between three and five. Furthermore, the stongest card in the 'Bisca', the card called 'manilha', is the 'seven', not the 'nine'.

Counting the points = Once the game finishes the points are counted.

The values of the cards are the following:

— 'Nine' ('manilha') = five points.

— 'Ace' = four points.

—'King' = three points.

—'Jack' = two points.

—'Queen' = one point.

The remaining cards have no value and constitute the so called 'base' ('base'), whenever they fullfill a round.

The counting is made round by round, i. e., each group of four cards that were played is counted.

There are several cases to take into account:

1. 'Full round' (Port.: 'vaza cheia') = which is constituted by for of the higher cards. For example, three figures and one 'Ace', or two figures, one 'Ace' and the 'manilha', etc.

This kind of round is worth the sum of each card's value plus one bonus point.

2. Four cards without value count for one point.

3. For each 'base' — one, two or three cards without value — a point is counted, besides the values which correspond to the remaining cards, i. e., 'Jack', 'Queen', 'four', 'two' = four points.

Each game finishes when one of the groups of players (partners) adds thirty-six points, which may correspond to several games.

If, by the end of two consecutive games, a group of partners does not achieve a victory, the partners will be exchanged.

Since the aim of the game is to score the greater number of points, one should try to win the rounds with the strongest cards.

One of the skills of the players consists in 'fugir o 'Ás' para não ser comido pela 'manilha" ('hiding the 'Ace' from the 'manilha''). Great attention is required in order to calculate the opponent's game and to play accordingly.

In Macao, we have also found the following version of the 'Manilha': 33

Number of players = It is played by partners (two by two) who must try to understand each others games by the cards that are played.

Finality of the game = The win, achieving thirty-six points or more. When this result is obtained the one game is finished.

Rules of the game = Before beginning the game, all the cards from 'two' to 'five' are removed from the deck.

In this case, each person receives only seven cards, the last one having an open value, and being the trump (like in the 'Bisca').

As each round is played the players must follow the suit.

Counting the points = Once the game finishes the points are counted.

The values of the cards are the following:

— 'Nine' ('manilha') = five points.

— 'Ace' = four points.

— 'King' = three points.

— 'Jack' = two points.

— 'Queen' = two points.

§4. THE 'CONQUIM'

In the Sixties, only a scarce number of people of Macao could still remember the rules of the 'Conquim' or 'Conquem'. Nevertheless, the older citizens said that, in their childhood, this was still a very popular game among the Portuguese born in Macao. One of our best informers, 34 who was the only one able to reproduce with a certain logic the several steps of this game, considered it to be of English origin due to the strangeness of its name, which he took for a local corrupted version of the word 'King'.

On the contrary, we think that it is a very ancient Iberian game, spread throughout the world by sailors and first settlers. If this is not the case, how then to explain that the word 'Coquim' which, by the way, is not of Chinese origin (the Chinese do not know the word nor the game), is also present among the North American Indian populations, together with other unmistakable traces of an Iberian introduction of card games?

We suppose that the Macanese name for this game comes from the word 'Conquien', a Spanish card game adopted by the American and transformed from the 'Rami'. It is natural that it was introduced in Macao from the Philippines, but it might have been directly introduced by the Portuguese.

According to S. Cullin, the 'Coquien' he found among the American Indians is a card game which the local tradition attributes to the sailors of Columbus. 35

Number of players = Four.

Number of cards = A common deck of fifty-two cards, of which seven are distributed, one by one, to each player. 36

Finality of the game = To be able to make certain combinations.

Rules of the game = The player who deals the cards, picks one at random from the pile he laid on the table. If the card is considered a good one, the player may keep it for himself, replacing it by one of those he holds.

To win the game, it is necessary to make one of the following combinations:

1. Four equal cards of the same kind and three equal cards of a different kind, i. e., four 'Kings' and three 'Aces'.

2. Three equal cards of the same value, and a sequence of four, i. e., three 'Kings' and one 'Ace', a 'two', a 'three', and a 'four', regardless of the suits. 37

3. Two sequences: one of four cards from 'one' to 'four', of the same 'suit', and another of three cards, from 'five' to 'seven', of the same 'suit' or of any other 'suit'.

4. A series of seven cards, all of the same“suit”, i. e., “three”, “four”, “five”, “six”, “seven”, “eight” and“nine”, or still “seven”, “eight”, “nine”, “ten”, “four”, “five”, and “six”. 38 In this case, the player who manages to obtain this unlikely association of cards, will win a double victory.

As the rounds are played, each participant throws a card to the table and picks from the pile one of the 'fechadas' ('closed') ones, like it happens with the majority of this kind of games. Once one of the sequences mentioned above is obtained, all the players must show their respective games in order to proceed with the counting.

Counting the points = In the uncomplete games the combinations which were initiated are separated from the remaining cards. The counting of the number value of these remaining cards (number value of the marks, and ten points for each figure — 'King', 'Queen' and 'Jack'), without distinction 39 will establish the value of the payments. Therefore, the smaller the number of points, the smaller the loss of each player who did not manage to complete a sequence. Each of the losing players, will have to pay the winner a previously agreed amount (in sapecas or senes), which is multiplied by the number of points resulting from the addition of the remaining cards.

Let us consider, for instance, the case of a player who lost and showed, at the end of the game, three equal cards, denouncing that he was trying to form a sequence of four, for he had 'Ace', 'three', 'four', 'five' and 'eight'. These remaining cards, which do not form a sequence as yet, add up to seventeen points (1+3+5+8). If the game had been agreed to be paid at ten senes per point (an extremely strong game for the time), 40 this player would have to pay one pataca and seventy senes to the winner.

Due to its purpose, i. e, to convert the alloted cards into certain groups (which the French call 'hasards' (lit.: 'random') — this game is similar to the 'Má-chéok', to the several kinds of 'Rami' (games which are also played in Macao), to the 'Picquet' and even to 'Poker'. However, only the 'Conquim', the 'Rami' and the 'Mé-chéok', may be considered as games with the aim of forming certain combinations. And, probably for that reason they found so many followers in Macao.

If, for instance, a player obtains thirty points and there was an agreement to pay one sene per point, he will have to pay thirty senes to the winner.

According to other informers, the 'Rami' was a game similar to the 'Conquem' or 'Conquim', which was played with ten cards distributed to each player. The only way of winning was to complete the ten groups, either playing with 'abertas' ('open') or 'closed' cards. In the second case, the riskier, winner is doubly paid.

In the 'Conquim' only four persons could play, whereas the 'Rami' could be played by any number. Two decks were used if the cards of only one were not enough for such a great number of players.

The counting is also different from the 'Conquim' for, as we have said, it is possible to win either with open or closed cards.

Generally, one only opens the game when the combinations are complete.

When a player wins the 'Conquim', his adversaries pay him only the equivalent to the number of added points, not counting the combinations previously completed, and which correspond to cards which are unmatched.

In the 'Rami', the points of the 'closed' cards are counted, regardless of the game that was made, i. e., of the groups already completed. So, when a player picks a great number of cards from the table and one thinks his going to win, each player should start to open the groups that are already formed for, like that, he will loose less. The counting of the 'Rami' is made by games. Successive games are played and the points of each player are added at the end of each game. In the beginning a limit of one thousand points, for instance, is established.

As the players reach the one-thousand points, they are excluded from the game. The last one — the one who manages to add less points — will be the winner of the game.

§5. THE 'SOLO'

This game was also very popular in Macao, being still played there in the beginning of this century.

Number of players = Four. However, the one who deals the cards does not play. Two of the remaining players associate against the third one, thence the name given to the game.

The value of the cards is the same as in the 'Manilha'. Albeit, in the 'Solo' one has to take into account the relative value of the suits, like in 'Bridge', that value is:

'Spades' ( ) = First.

) = First.

'Hearts' ( ) = Second.

) = Second.

'Diamonds' (◆) = Third.

'Clubs' ( ) = Fourth.

) = Fourth.

Rules of the game = Each player gets twelve cards and must order them according to their relative values, taking into account the figures and suits. Whoever verifies he has a good game, i. e, no more than five rounds to loose, says: — "I request [...].", saying, then, the name of the suits of which he/she has the best and the biggest number of cards; if another player considers that his/her own game is also strong he may "request" and if his suit is stronger than the one of the first player to speak, he will be the 'solo' and his 'suit' will be the trump.

The other two players ally against him. If none of the players considers he has enough game to defy his adversaries, the game will not be done and the cards are shuffled again and dealt by the player who seats to the right of the player who dealt the cards in the previous game.

The rules of this game are similar to the 'Manilha', and the final points are counted in the same way.

This game, which was somewhat simplified in Macao, corresponds to the famous 'Hombre' game — the Spanish card game which Pierre Berloquin considers to be "[...] one of the possible limits of all the rounds games [..]". It represents a build up of the feudal hierarchy. Different ranks for the 'Black' and the 'Red', for the trump and the other suits. Napoleon Bonaparte favoured the 'Hombre' for four partners, which resulted in the famous European 'Quadrille' of the last century, hoping to compete with the English fashion of playing 'Whist'. 41

Let us compare the 'Solo' with the Iberian 'Hombre'.

The 'Hombre' was considered the Spanish game par excellence, much in the same way as the 'Whist' was characteristically English, and the 'Monte' (lit.: mount) characteristically Portuguese. The hierarchy and the protocol are complex. The high cards are all-mighty over the low ones. In this game is reflected a society dominated by a proud and despotic aristocracy.

From the point of view of the nature of games, the 'Hombre' is one of the possible limits of bidding games.

The original rules were simplified and the game that reached us is longer, and for that reason, as complex. The number of players used to be three, but in France, Napoleon transformed this game in a foursome to compete with the 'Whist' of the British, his enemies.

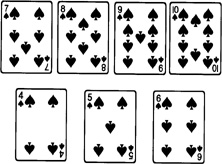

Finality of the game = The finality of the game is to make the maximum of bids. Only forty cards are used, i. e., the fifty-two of a complete deck except for the four 'tens', 'nines', and 'eights'.

The order also changes according to the colour:

'Spades' and 'Clubs': 'King', 'Queen', 'Jack', 'seven', 'six', 'five', 'four', 'three', and 'two'.

'Diamonds' and 'Hearts': 'King', 'Queen', 'Jack', 'Ace', 'two', 'three', 'four', 'five', 'six', and 'seven'.

The trump adds its own influence to this series.

The 'Ace' of 'Spades', or 'spadille', is the stongest card.

The third card of the trump is always the 'Ace' of 'Clubs'.

The second card of trump, or 'manille', is the smallest of the cards of the colour chosen for trump. This card is a 'seven' or a 'two', depending if the trump is 'Black' or 'Red'. When the trump is 'Red', the 'Ace' goes over the 'King' and is called 'ponte' ('bridge'). These three cards are the 'matadores' ('killers'). The gains are made with chips. Each player has one-hundred chips at the beginning of the game as well as a small jar.

Before the cards are dealt, each one of the participants in the game places nine chips inside the jar. Following this, the dealer distributes nine cards — three by three — to each of the players.

One of them — a man — declares that he will make a greater number of rounds than his adversaries, who in their turn will unite against him. After this defy, each one of the others, starting from the one to the left of the dealer, must say if he wants to be the 'homem' ('man'). If he passes, he will have to put six chips in the jar. If he accepts, will state the colour of the trump and choose one of the three following alternatives:

1. To play 'sem tomar' ('without taking'): The player picks up five cards without discarding. His adversaries may discard.

2. To play 'tomando' ('taking'): The player has the right to pick up more cards than his adversaries, keeping the right to discard.

When the three players pass, the cards are dealt again, and the amount in the jar will increase with new entries.

The 'homem' ('man') will be the first to discard, if the second alternative was chosen. If it is the first, the players will start discarding starting from the one to his left. Each one throw as many cards as he wishes and pick the same number from the pile.

3. The player to the left of the dealer throws the first card. The cards must be thrown according to the request colour. The 'killers' cannot be forced to play by the trumps of lesser value. Only a higher trump will force a lower one to be discarded.

The two partners who play against the 'homem' are allowed, by using short sentences — beginning by the word 'gano', for instance, 'gano de rei' (lit.: the 'King's 'gano"), or a similar sentence — avoid that when his neighbour plays a 'Queen' the next will play the 'King'. In Macao, the meaning of the word 'gano' was unknown.

The 'homem' wins when he manages to make more rounds than is companions, i. e., when he collects more cards. If they play by the second alternative, the 'pote' ('jar') wins. If they play by the first alternative the 'homem' receives twelve chips plus one more for each 'killing' of each adversary.

If the 'homem' is able to accomplish the 'vale' ( i. e., all the rounds), he should receive, apart from the jar, half of its contents from each of his adversaries.

If the 'homem' looses, being unable to collect the greater number of cards, he must add to the jar the same amount it contains (in the first of the cases mentioned above). In the second case, he must also pay, to each of the others, the double of what he would have received had he won the challenge of the initial contract.

In our opinion, this game is a clearly a version of the extremely old Iberian game of 'D' el hombre'.

§6. [CONCLUSION]

For all we have shown, it seems possible to conclude that, throughout time, there was a double course of card games: first from the Orient to Occident, and then in the opposite direction.

On this second route, the role of the Portuguese and Castillian during the Golden Age of their expansion is, in fact, undeniable in the worldwide spreading of card games.

The ethnographic data collected in Macao, where Chinese and Occidental card games are played side by side — often with hybrid rules — clearly testify to that.

Moreover, the adoption of cards from Europe by the Chinese is very recent.

This late introduction is underlined by the name for which they are known: 'Po ká' ('Poká cards') a name derived from 'Poker'. A combination game similar to the Oriental games, that was introduced along with them.

Thence the interest that the collecting of the rules of the old Occidental card games preserved in the collective memory of the Portuguese descent Macanese deserved from us, when in the sixties and seventies we undergone our field work on that colony.

It is one of the testimonies of a vanishing cultural identity.

§7. [EPILOGUE]

Anonymous, forbidden, considered sinful, the card games, the ancient Iberian suits took gamblers before the Tribunals of the Holy Inquisition, but they also served as entertainment and motive for social cohesion for the dreamers on the remotest places on Earth, exiled from a Europe which was to small.

Translated from the Portuguese by: Rui Cascais Parada

NOTES

1 BULLET, A., Recherches Historiques sur les Cartes à Jouer, Lyon, 1757.

2 RIVE, Abbé, Éclairissements Historiques et Critiques sur l' Invention des Cartes à Jouer, Paris, Chez Didot, 1779.

3 HARGRAVE, Catherine Perry, A History of Playing Cards, New York, Dover Publications Inc., 1966, p.247.

4 CULLIN, Stewart, The game of Ma Jong: its origin and significance, Offprint of "The Brooklin Museum Quarterly", New York, Oct. 1906, p. 10

5 HARGRAVE, Catherine Perry, op. cit., p. 247 — On Salvini from eighteenth century Florence, Italy.

6 This game, similar to the 'Quadrille' of the end of the last century, is a card game that went from Spain to the rest of Europe. It was very popular in the English Court of the eighteenth century, where it was played in a triangular shaped table.

7 BULLET, A., op. cit., and BRUNET, J., in 1886 and 1898, admit a possible Catalunian origin of card games, comparing them with those of India and China. They analyze the likely relationships between Oriental and European cards. Other authors consider that cards entered in Europe through Genoa or a port on the Iberian Peninsula.

8 COVELLUZO, 1480.

9 Richard Lionheart, according to an old manuscript of the British Museum, brought chess to from Palestine to England.

10 On a miniature of the fifteenth century, in the Bibliothéque de Rouen, France, it is possible to see several people playing cards with numbered decks and figures of kings.

11 FAJARDO, Francisco de Luque, Fiel desengaño contra la ociosidad y los juegos, Sevilla, 1603.

12 CUEVA, Juan de la, De los inventores de las cosas — According to the author, Villan was natural of Barcelona and a child of humble origin.

13 Ordenações do Senhor Rey D. Afonso V, Lisboa, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, [n. d.], bk. V, tit. XLII — Facsimile reproduction of the edition printed in Coimbra, by the Real Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, 1792.

14 Ordenações do Reino de Portugal recopiladas por mandado de El-Rey D. Philippe I de Portugal, Lisboa, Pedro Craesbeck Imp., 1603, bk. V, tit. LXXXII.

15 St. Bernard of Siena, in a sermon given in Bologna, in 1423, said that card games were invented by the Devil. Thence, maybe, their quick spreading and popularity. During the fifteenth century, renewed and more violent ecclesiastic attacks resulted, so it seems, in a greater taste for the forbidden fruit — the game of suits.

16 PLATTNER, Félix Alfred, Quand L'Europe cerchait l'Asie, Paris, Casterman, 1954.

17 PERES, Damião, Viagens e naufrágios célebres dos séculos XVI, XVII e XVIII, 4 vols., Porto, 1937-1938

18 HARGRAVE, Catherine Perry, op. cit., p.248 — In the fifteenth century, Toulouse, Thiers and Rouen manufactured great quantities of card games to supply Portuguese, Spanish and Flemish ships.

19 ALLEMAGNE, Henry René d', Les cartes à jouer du Quatorzième au Vintième Siècles, Paris, Hachette et Cie., 1906.

20 HARGRAVE, Catherine Perry, op. cit., p.17.

21 Idem.

22 In Belgium there is a Museum of Turnhot, located in a sixteenth century manor, where several kinds of playing cards are displayed alongside with the instruments for its manufacture. The reason for the choice of this particular place lies on its centuries old tradition in card manufacturing — cards that were destined both to Western and Eastern countries.

23 We should not mistake the Portuguese acception for the Spanish, which corresponds to the ensemble of cards in general, at least since the eighteenth century.

24 One should note that 'palos' was the Castillian name of the four suits or series.

25 The symbol of incarnation is a vessel of water. The colour of Vishnu is blue. A colour that appeared on the first European cards, together with red or orange and instead of black.

26 SILVA, João José da, Repertório Alphabetico e Chronologico ou Indice Remissivo da Legislação Ultramarina desde a Epocha das Descobertas até 1882, Macau 1886, p.16.

27 TAVERNIER, J. B., Les six voyages de Jean Baptiste Tavernier, l' écuyer du Baron de Aubone, Qu'il à fait en Turquie, en Perse et aux Indes [...], Paris, 1712.

28 BACL: Série Vermelha (Red Series), MS. 223. —PIEDADE, Barreto Justiniano Augusto da, Summario Chronologico da Legislacão Portuguesa desde as Ordenações do reino de 1603 até às de 1860, Margão, Typ. do Ultramar, 1864.

29 The 'manille' is, in the popular Spanish 'hombre' the smallest card in suit which is considered the trump. To Bluteau (eighteenth century) the 'manille' was also a lesser card.

30 This is what the Christian of Mallaca say of the 'Manilha':

— "E jogo cristã." (—"Its a Christian game.").

It is played by four persons with decks of fifty-two cards, of which the tens are excluded. Twelve cards are distributed to each person, the final card is the trump. Each player is forced to follow the suit covering or cutting with trump. At the end the 'ôlo' (points) are counted:

— 'Nine' ('manila') = five points.

— 'Ace' ('as') = four points.

— 'King' ('Rei') = three points.

— 'Jack' ('cabalo') = two points.

— 'Queen' ('sota') = one point.

Each group of different cards in a round is worth one point.

31 Dona Celeste Araújo, Dona Alzira Rocha, Dona Alice Gutierres, and Mr. Francisco da Silva Paula

32 In my childhood in Portugal, we played the 'Bisca' with similar rules to the 'Manilha' of Macao, but only with three hand cards and the 'Ace' being the strongest card followed by the 'manilha' of any suit.

33 Informers: Dona Bárbara de Jesus and Dona Júlia Remédios — two old ladies in the Asilo da Nossa Senhora da Misericórdia (Asylum of Our Lady of Misericordy), and an anonymous visiting relative.

34 Mr. Constâncio José Gracias.

35 CULLIN, Stewart, op. cit. — According to the author, the North American Indians received playing cards via the Spanish, which seems to be prooved not only by the symbols but also by the names given there to the different suits.

36 The number seven has a special place in Western magic and superstition.

37 Some informers consider that this sequence must be of the same suit, whilst others do not. According to some this sequence must be 'Ace', 'two', 'three', 'four', and according to others it may be, for instance, 'five', 'six', 'seven', 'eight'.

38 Not all the informers agree that this sequence should be doubly paid.

39 The lack of distinction between the values of the figures is also one of the elements pointing to the antiquity of this game.

40 Gambling used to be done with sapecas or with senes (Chinese copper coins with our without a central whole).

41 BERLOQUIN, Pierre, Le livre des jeux, Paris, Stock, 1970.

* Ph. D (Lisbon). Lecturer in Anthropology, Instituto de Ciências Sociais e Políticas (Institute of Social and Political Sciences), Lisbon. Consultant of the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Fundação Oriente (Orient Foundation). Author of a wide range of publications dealing, primarily, with Ethnography in Macao. Member of the International Association of Anthropology and other Institutions.

start p. 87

end p.