There is a little-known city in the south of China1, close to Hong Kong, sitting on the Pearl River Estuary which, nevertheless, enjoys an absolutely unique position in the world. It is known internationally as Macau, as Ou-Mun in Guangdong Province and Ao-Men in the rest of China2.

Since 1979 it has been designated as Chinese territory to be administered by the Portuguese until the 19th of December, 1999. On this date it will pass into the People' s Republic of China at the beginning of a transition period which will last for fifty years. During this time, both the Portuguese language and laws will remain in force, at the same time, of course, as their Chinese counterparts.

This situation, the result of diplomatic talks and agreements signed by both countries, also reflects the profound changes which have taken place in both countries since the 1970's. In Portugal, one of the main consequences of the 25th of April Revolution in 1974 was to bring to a close an inadequate colonial policy in its African and Asian territories. This facilitated a more open dialogue with the other nations of the world, particularly with China with whom diplomatic relations were re-initiated on the 8th of February, 1979. The internal changes taking place in China itself, which led, in 1983, to Deng Xiaoping's policy of one country, two systems aimed at the reintegration of Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, created an atmosphere in which the complex issue of Macau's sovereignty could be resolved. This was formally settled with the signing of the Sino-Portuguese Joint Agreement on the 26th of March 1987 and ratified the following year.

Why, however, is Macau's administration Portuguese? Macau itself is a small area of land measuring 17.5 square kilometres where three hundred and fifty thousand people (3-4% of them Portuguese or of Portuguese origin) live3.

We only have accounts, both Chinese and Portuguese, dating from a relatively late date (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries).

Here we risk getting entangled in a complex historiographical issue unless we can refrain from falling in with preconceptions and centralized and/ or politically biased explanations. Even if we take a more academic approach, which in my opinion is also fruitless, and try to base our argument on concrete proof which could clarify the issues once and for all, it is highly unlikely that there is (or ever has been) any written document stating that Macau was donated, or even rented, to the Portuguese by China in the sixteenth century.

Obviously I do not dismiss the value of evidence contained in documental sources. However, we all know that in the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese settled in Macau (and until much later on) chronicles and even reports were produced with a strong political, religious, even national bias both in the East and the West. That is to say, the chroniclers, travellers, administrators, missionaries, and mandarins did not keep themselves to the task of simply reporting the facts. They flavoured their accounts with their own values, opinions and explanations, in line with their mentalities, customs, civilisational rules and the intentions of their countries and/or religion.

Let us take a look at José Mattoso:

Until the emergence of structural history, and especially after the appearance of the history of mentalities, historians were not aware that archives had this function of operating a selective work from the materials left to posterity. Until fairly recently, historians were still perceiving the contents of archives as being legitimate documentary texts. In other words, they were seen as satisfying the needs of current intercommunication and were not in fact understood to be monumental texts produced by the powers-that-be to perpetuate memorable events in an attempt to perpetuate that same power. Consequently, there were no doubts raised as to the veracity of the documents from archives so long as they had been shown to be genuine....

There was no notion that archives themselves were a tool for moulding the memory, a tool wielded by the powers-that-be. 4

Rocha Pinto also discusses this point with regard to travel literature:

The overwhelming majority of written material does not correspond to the logic of historical construction as informed by the hegemonic ideology of the chronicles. It uses narrative as a structure and tries to preserve history for future generations (as in official chronicles) even though these documents were no longer merely passive receptacles for national sagas because, by now, their authors were aware of personal experience and extended their vision of the world through personal and emotional perspectives, providing a background of social commentaries even though the reports were often commissioned by third parties.

None of the above prevents the majority of written material from becoming, from the outset, an enemy to be defeated through scholasticism and the dominant classes. 5

LOOK NOW TO THE SAGES OF THE SCRIPTURES

WHICH SECRETS ARE THESE FROM NATURE?

Luís de Camões, in Os Lusíadas (1572)

On the other hand, the Humanist movement6, in its early stages in the West, and which was to culminate in the universalisation7 of Man which marks the trends of our own century, was still far from being a given, assumed fact.

In Europe, Catholics and Protestants sparred against each other in religious squabbles; the Inquisition was persecuting Jews and defenders of 'outrageous' ideas which opposed the truth as proclaimed by kings and popes. At the same time, the voyages of Portuguese and Spanish navigators were opening the eyes of the West to a new perception of the world. They gazed in amazement, respect and curiosity at the new8 (synonymous with different) peoples9 about whom, until then, they had only10 heard legends and fantastic tales11. Similarly in China, an empire with an ancient civilisation and culture which had been reluctant to let foreign influence permeate its borders (not least because of the barrier created by ideographic, monosyllabic, and equally impermeable language), regarded these barbarians as strange. Their encroachments were rejected because their behaviour, culture, modes of thinking and acting were disturbing elements far from the standardised civilisational habits and social, political and philosophical principles of the prevailing Confucianism which guided and upheld the traditional values of China.

These, then, were the patterns of thought in place at the time of the first contacts between the Portuguese and the Chinese in the early sixteenth century. By this point, Western man had already passed, in Rocha Pinto's words, "from an absolute to a relative position in space12, at the expense of a mythical space".13

The Portuguese came from a small, underpopulated14 country with few financial resources. Located in the westernmost point of Europe15 and the Iberian Peninsula which it shared with the recently unified Kingdom of Castile16, Portugal had long been trying to gain control of the seas. After all, half of Portugal's borders are on the sea. The Portuguese were pioneers in Europe and they did succeed in fending off Castile in taking charge of the seas. They were motivated, it is true, by commercial and religious purposes, but they also responded to the draw of adventure and curiosity. They reached the furthest point known to Europe since antiquity, Cathay17 which until then had been as mythical as it was fascinating. Then they travelled on to the Lequias (Kingdom of Ryuku) in Japan of whose culture, civilisation, organisation and government they really knew little or nothing at all. At the same time, they were involved in dismembering the powerful commercial and religious rule of Islam18.

China had recently closed her doors following a period of equally glorious maritime expansion and adventure under the Ming dynasty emperor Yung-le (1403-1424). During this period his most outstanding navigator Zheng He (1371-1433) had reached the eastern coast of Africa. Yung-le's reign was also marked by the increased prosperity arising from foreign trade activities19 in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. The main features of this were polarisation, imperial monopolism and a policy of paying tribute. From the fifteenth century onwards, however, China turned towards restructuring and stabilizing within its own borders, demonstrating great concern with defence and taxing of the coastal areas. In the absence of a uniform policy (for policy read 'desire') on foreign trade, China would long vacillate between permission and prohibition. The truth remains that the interests of the coastal areas, which were traditionally involved in this trade (which was carried on illegally) were closely connected with this movement, particularly because these regions had been in conflict with the Chinese hinterland which was traditionally agricultural.

In my opinion, it is precisely because of this situation, and because of the Portuguese ability to adapt and communicate with their surroundings in other words the sometimes tacit, sometimes explicit understanding between the Portuguese and the Chinese, which has allowed Macau to continue for over four hundred years. Macau is perhaps one of only a handful of places in the world which have borne witness to the coexistence of two entirely different cultures which have managed to retain their own identities over the centuries. It may be that the secret of this plural history lies in the parallel legal and institutional entitlements which, although they have been adapted, have existed within the same territory for so long.

YOU SHALL ASK FOR THE CHINS,

AND FROM WHENCE THEY COME.

D. Manuel, King of Portugal (1508)

Once they had managed to get past the massive obstacle presented by the Cape of Good Hope(which the Portuguese navigator Bartolomeu Dais succeeded in doing in 1487) and on to the coasts of India with Vasco da Gama's armada of 1498, adventurers tried to set up commercial contacts along the China coast. The king of Portugal, Dom Manuel, was extremely interested in making contact with China as can be seen in the instructions which he handed to Diogo Lopes in 1508 for the first Portuguese expedition to Malacca:

You shall ask for the Chins, from whence they come and how far off[it lies], how often they visit Malacca and the other places where they trade, the goods they carry, how many ships come each year, how are they made, if they will come next year, if they have factories or houses in Malacca or any other land, if they are wealthy merchants, if they are weak men or warriors, of they have weapons or artillery, what they wear, if they are corpulent, and any other information about them, whether they are pagans or Christians, if their land is great, if they have more than one king, if any Moors or other people who do not share their laws or beliefs live amongst them, if they are not Christians, what is their faith, what customs they follow, where their land lies and which are its boundaries" .20

As early as 1513, Jorge Álvares set off for Malacca, strategic port which was extremely important for trade in the Far East. Formerly, Malacca had paid tribute to the Kingdom of Great Clarity but it had been conquered by the Portuguese in 1511. By the time he dropped anchor in Taman21, where he was to die and be buried some years later, Álvares must have been the first of many Portuguese to travel to China in the sixteenth century.

What is known about this period, between then and the 1550s when the first Western references were made to Macau, and the Portuguese began to establish a settlement between 1552 and 155722 on the little peninsula known as Hoi-Keang (Hao Ching Ao23) at the mouth of the Pearl River, is really very vague and diffuse despite the fact that there are references to Tomé Pires's embassy to China and the accounts written by Fernão Mendes Pinto. 24 Tomé Pires disappeared without trace after having failed to establish commercial and diplomatic contacts between Portugal and the Celestial Empire. As was to happen with the next embassy in 1521, this time led by Martim Afonso de Melo Coutinho who came from Lisbon and not India, Tomé Pires was unable to make contact with the emperor although he had a lengthy, comfortable stay in Canton.

Those were long years of journeying, adventures, violence, clashes, and personal voyages which lay below the surface of these pioneering activities. They were years of clandestine, unlawful contacts (and because of this there are so few documents) with a power which was only too aware and proud of its ancient political, institutional social and cultural values. China was divided between those who supported foreign trade (particularly the Province of Canton) and those who supported total isolation for the country. In the end, this situation resulted in not only allowing the Portuguese to settle in this tiny spot on the edge of the vast Chinese empire, but also managing the way in which they lived there, a move which was sparked off by China's own interests, both on a regional and national level.

The Portuguese settlement gradually took on a more permanent nature and became what is now known as Macau, City of the Name of God in China even though all trade with Westerners had been prohibited in 1522.

The way in which this change occurred, a change which resulted in the Portuguese being allowed to remain for over four hundred years on land belonging to the Celestial Empire, is another story which gives rise to controversy and never-ending discussions.

Because there is an absence of documentary material as we have seen, it is impossible to reconcile the differing versions proffered by and even within each country. Some people insist that Macau was donated in perpetuity to the Portuguese as a reward for having aided the Guangdong authorities in ridding the coastal waters of the pirates which had, for so long, been wreaking havoc in the area. This event took place when the Captain-major of the China voyage managed to establish trading links and peaceful relations with China in 1554. Others claim that the Portuguese were allowed to stay because they paid an annual rent while yet others, particularly Chinese writers from the middle of this century, are of the opinion that what happened was a case of territorial usurpation. These views are, naturally, coloured by the different interpretations given to facts in different historical periods and also by the variations in nationality and convictions of those who defend them25.

THE FAT-LONG KEI WERE THEN ABLE

TO COME IN A DISORDERLY FASHION...

AS TIME WENT ON, THEIR PRESENCE

BECAME A RECOGNISED FACT.

Tcheong-U-Lum and Ian-Kuong-Iam

Ou-Mun Kei-Leok (XVIIIth century)

What we know for certain is that the Portuguese did come and settle in this little harbour near a temple dedicated to the goddess Neong-Ma (Neang-Ma, Tin Hau or A-Ma). The area was known as the Bay of A-Ma; changing to A-Ma-ao or A-Ma-ngao from which some experts26 think it gained its Western name, not, it must be said, without some controversy.

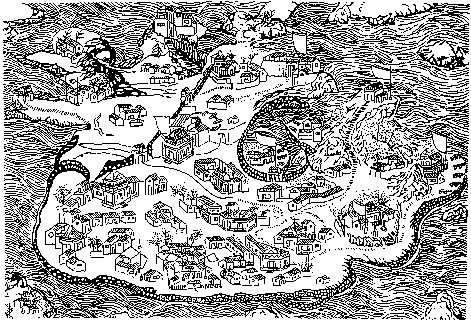

Chinese Woodblock view of Macau from the Ou-Mun Kei-Leok

Chinese Woodblock view of Macau from the Ou-Mun Kei-Leok

Once in Macau, the Portuguese laid the foundations for a longlasting, profitable trading relationship with the Far East. They slowly made their way into China and traded between China and Japan for almost a century (1543-1639). These activities left a cultural and civilisational mark on this part of the world through commerce, religion, technology, gun-powder and love. They were helped from a very early stage by the representatives of the Catholic Church which had made Macau a diocese in 1576. It was thanks to the Jesuits, in particular, that Catholicism spread so widely throughout the Orient, including Japan and China, in addition to the contribution made by Western culture and civilisation in themselves. The Jesuits made Macau the centre of their activities, with the focal point being what is commonly referred to as the College of St. Paul. The famous facade which dates from a later period (around 1640) than the construction of the Church of the Mother of God itself (built between 1601 and 1602) still stands witness to their actions. The main section of the church was destroyed in a fire on the 26th of January, 1835. The extent of their contribution can easily be seen when we look at figures such as St. Francis Xavier who died in Sanchuan, China in 1552 and Matthew Ricci the distinguished mathematician and cartographer who gained acceptance in the inner sanctuary of the imperial court of China.

In the very beginning27, the Portuguese were the only Westerners in this region and their language was adopted as a new lingua franca28 of the Orient. This Portuguese was a simplified, variable version of the mother tongue because it was combined with other languages of the region, particularly Malayan and Indian languages from coastal areas, for instance Gujerati, Marathi and Konkani. Portuguese was not only used for writing official documents concerning contacts between peoples in the East and the West, but it was also employed in communication between the latter, in other words between the Dutch, the English, the Danes, Spaniards and so on. Portuguese was current from India to the Mauritius Islands, from Sumatra to Japan, Batavia to Sri Lanka, Celebes to Bicobar and even within China, not forgetting Thailand and Burma as well29.

From the seventeenth century onwards, the Portuguese were involved in conflicts with the Dutch (who had taken Malacca in 1641) and the English over the profitable monopoly on trading silk for silver. There was great competition for the chance to take products ranging from tea, porcelain and furniture to silk and even in later years manpower30 from a distant, exotic and refined Orient to European markets. Macau thus became the target of successive attacks by the Dutch. The most violent attack came on the 24th of June, 1662, and the Portuguese victory is still celebrated on this day. In turn, the English, who held the reins of technological progress which, with introduction of the steam engine, gave them the opportunity to revolutionise transportation and production across the world, began to monopolise China's foreign trade. They used Macau, taking advantage of the old alliance with Portugal, to gain entry to the empire. This was the situation in the early nineteenth century, a situation in which they would be the victors of the Opium War of 184231.

As early as 1808, when they were engaged in above-mentioned disputes with China, the English had tried to set up a military post in the small harbour under the pretext that a French boat had been given shelter in Macau. Later, and once they had won, the English, closely followed by almost all the foreign powers, installed themselves on the Yangtse River in Shanghai and other cities in the south of China. They were to further increase their imperialist economy in 1841 with the creation of Hong Kong, a city which would become one of the word's most important financial markets. The presence of this other European power in the Far East had a major effect on the economic stability and society of Macau. This was what had already happened two centuries earlier as a result of Japan's prohibition on the foreign trade which had been the reason for Macau's existence, growth and the presence of the Portuguese there.

This blow to Macau was followed by a period in which China demanded increasing control and monetary compensations which lasted until the introduction of a more assertive colonial rule, symbolised by Governor Ferreira do Amaral32 and facilitated by the international situation and the dependence created by military defeat in China. One of the more flagrant examples of this was the creation of a Chinese customs house in Macau, the Ho-pu in 1688, and the order for a mandarin, the Tso-tang, to be stationed in Macau in 1736. These meaures led not only to a heavier financial burden for both the Portuguese and locals living in Macau, but also to political, economic, social, racial and even religious conflicts. In an attempt to bring this situation to a peaceful conclusion by negotiating, clarifying and regulating it, Portugal sent three embassies to Peking. The first one went in 1667 led by Manuel de Saldanha, the next in 1726 led by Metelo de Sousa e Menezes, and the third in 1752 led by Pacheco de Sampaio. None of these was sucessful. It was only in 1887, after over two decades of negotiations, that the Lisbon Protocol Agreement was signed, agreed and ratified in the Treaty of Commerce and Friendship signed by Portugal and China on the 28th of August of the following year. This Treaty recognises the Portuguese occupation of the territory of Macau in perpetuity but, as it was done on the basis of the international situation with which China was confronted, both this and other treaties were later to be denounced.

Even so, the issues inherent to the territorial boundaries of Macau which had first been raised with the building of the Portas do Cerco33 border gate in 1573 (a clear indication from China of the interest in keeping the trading post open but tightly controlled), would remain unsolved until our own century. Of most significance is the fact that it was common law which ruled both this and other issues.

This lack of definition did not in any way prevent Macau (classed as a city in 1586) from adopting markedly Portuguese forms of government and sovereignty. This was obvious in the organisation of municipal power with the city council, the Senado da Câmara, later called the Leal Senado which was established in 1583. Judicial powers were appointed in 1587 and there was a progressive strengthening of central control in the form of a Captain-General, and later the governor. Macau was part of the Estado da Índia34, the representative of the Crown, until the 20th of April 1844. From then on, Macau, along with Timor and Solor, became one of Portugal's overseas provinces.

From the late eighteenth century onwards, the city expanded until it gained its present shape. The boundaries of the city have changed due to constant land reclamation and also because of the huge influx of people (mostly from China) which has increased the population significantly. This has led to a change in the appearance, architecture, daily life, customs, atmosphere and most importantly the economy of the city. This trend became most obvious in 1937 with the Japanese invasion of China and during the Second World War when Hong Kong was captured by the Japanese in 1941.

The city of Macau grows day by day at an astonishing rate. Since 1974, the city has been linked to the island of Taipa by the Nobre de Carvalho35 Bridge and Coloane was joined to Taipa by a causeway in 1968. The territory, which now attracts tourists from all over the world who come to gamble and, from 1954, to see the Formula III Grand Prix, is hardly the same quiet little place where Sun Yat Sen took refuge before announcing the formation of the Chinese Republic on the 10th of October, 1911 and becoming the first provisional president when it was officially proclaimed on the 1st of January, 1912.

Macau has borne witness to all of this because, under Portuguese administration, it has managed to resist the mercantile, imperialistic trends which had conquered and dominated new markets. It has managed to resist the upheavals which have taken place this century and the internal changes on China's own political stage. Naturally, there have been reverberations, and Macau has had to change with the times, times which have generated their own changes at every level, not least to Macau's unique status in the world.

The territory is now preparing for the transition procedure which was started in 1985. The definitive hand-over will take place in the year 2049 when Macau will be absorbed into China once and for all.

NOTES

1Macau is located on the South China coast around sixty kilometres southwest of Hong Kong, at 22o 06' 40"N to 22o 13' 01"N and 113o 34' 77"E and 113o 35' 20"E.

2According to T'ien-Tse Chang, Sino-Portuguese Trade from 1514 to 1644. A synthesis of Portuguese and Chinese sources, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1934, p. 87, the most appropriate Chinese name is Hao-ching-ao meaning the Bay of Hao-ching. cf. p. 6.

3According to the initial results of the most recent population census taken on the 31st of August 1991. These figures have been disputed, which is not surprising when we take into account Macau's floating population which also includes a component of boat dwellers and also the fact that previous estimates had put the population at around 460 thousand inhabitants.

4"Os Arquivos Oficiais e a Construção Social do Passado" in A Escrita da História. Teoria e Métodos, Lx, Editorial Estampa, 1988, p. 91.

5A Viagem. Memória e Espaço, Cadernos da Revista História Económica e Social, (11-12), Lx., Sá da Costa, 1989, p. 91.

See also the introduction to Rafaella D'Intino to his anthology Enformação das Cousas da China. Textos do Séc. XVI, Lx., Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda, 1989, pp. XⅢ-XXⅢ

6Cf., for example, the introduction to Vitorino Magalhães Godinho to Joáo Rocha Pinto's work, particularly the passage on pp. 10-11.

7João Rocha Pinto, op. cit., p. 27.

8 Even though this view was ab initio characterised by the immediacy of the description and, at times, mediated by an enmeshing of myth and magic with an intuitive interpretation of perceived reality as Rocha Pinto points out, op. cit., pp. 52, 71, 74 and 75.

9Various authors, including Rafaella D'Intino, (op. cit., pp. XⅢ-XXⅢ) have developed the notion that the scanty information on China received by Western culture-particularly from the highly influential reports from missionaries, most especially the Jesuits - provided writers in the West from the sixteenth century onwards with the concept of a Utopia (cf. note 17), in which they formalised the expectations created in the imagination of the Western mind by what was possibly the most significant myth of Christianity: that of the kingdom of Prester John. Cf. also Suma Oriental by Tomé Pires (ed. by Armando Cortesão, in an edition which includes the Livro de Francisco Rodrigues, Coimbra, Universidade de Coimbra, 1978, pp. 252 et. seq. ) which, although it was published at an earlier date, was possibly not so widely circulated as the work cited above.

Some years later, in 1563, Garcia da Orta recorded similar observations although they were not obtained first hand. For over thirty years Garcia da Orta lived in India, working as a doctor and devoting himself to the study and description of medicinal plants (he was posthumously condemned by the Inquisition). He published his results in Colóquio dos Simples e Drogas e Cousas Medicinais da India in which he mentions the Chinese empire:

Due to their leisurely lifestyle, the inhabitants of this region are prone to overeating...

They are the Chinese of Asiatic Schita, who are regarded, nevertheless, as a barbarian people but respected as being very industrious in their business and manual labour. In literary knowledge they are greatly superior to any other region. They have written laws similar to the Imperial Law as can be seen from a book with their laws which, from what I have heard, can be found amongst these Indians...

I have also heard tell that they have different levels of education and awards and the government of the king and the entire kingdom is entrusted to learned gentlemen. Their paintings show men reading in an elevated position and those listening clustered round their feet. The methods they use for printing are so ancient their origins are lost in the mists of time and they have always been used by them.

Translated from the Versão Portuguesa do Epítome Latino dos Colóquios dos Simples de Garcia da Orta, by Jaime Walter and Father Manuel Alves, Lx., Junta da Investigação do Ultramar, 1964, pp. 168 and 173.

10Cf. also those contacts made between China and Europe prior to the sixteenth century which are not always taken into account but have been collected by Benjamim Videira Pires in Os Extremos Conciliam-se (Transculturação em Macau), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 1988, particularly chapters Ⅰ to Ⅲ, pp. 11-33.

11Cf. for example, the comments of the Florentine Brunetto Latini (writing in 1260) in his book Tresor about India: In India the air is so good that there are two harvests each year and, in the winter, there is a sweet, pleasant wind. Because the Indians have never been expelled from their lands, there are five thousand cities, all well populated... To the east lies the land of the pepper, crossed by a great river; on one side there are elephants and other wild animals, on the other men and a great quantity of precious stones, apud Augusto Reis Machado in his introduction to op. cit., p. 8.

There is also information about silk, although the silk worm had already been introduced to the West as is explained by Rafaella D'Intino, op. cit., note 8 to p. XⅢ: Seres che difoglie e di scorze d' arbore, per forza d' acqua, fa una lana ond' elli vestono loro corpi.

12Op. cit., p. 51.

13Cf. Vitorino Magalhães Godinho, "Entre Mito e Utopia: Os Descobrimentos, Construção do Espaço e Invenção da Humanidade nos Séculos XV e XVI" in Revista de História Económica e Social, Lx., (12), July-December 1983, pp. 1-43.

14It had a population of around half a million in 1500 in a Europe with around 95 million. Apud Costa Pinto, op. cir., p. 66.

15For more on the fifteenth century European expansion as a collective task (although still subject to different paces and temporal variations) and the result of systematic planning, cf. the summary and bibliography in Rocha Pinto, op. cit., particularly pp. 63-67, 71-75 and 96.

16The Treaty of Tordesillas signed after lengthy negotiations between Portugal and Castile on June 7, 1494, signified the carving up of the New World on the authority of Pope Alexander VI. All territories to the east of the meridian lying 370 leagues from Cape Verde were given to Portugal while Castile kept those to the west.

17The name, also written as Citeu, Khitai or Khata was derived from the Kitans (Qitañ), the Manchu people who dominated northern China from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. This was how China came to be known in the West from the Mongol empire onwards (1278-1368), particularly due to Marco Polo's experience. In ancient times, from Pliny, Strabo and Ptolemy onwards and up until the Middle Ages, China was known as Seres from the Latin word sericum meaning silk. It was only in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries that-this territory was identified as China (cf. Eduardo Brazão, Em Demanda do Cataio. A Viagem de Bento de Goes a China (1603-1607), Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, 2nd edition, 1989). The name China may have been derived from the Ch'in dynasty in the 3rd century BC (cf. Samuel Couling, Encyclopaedia Sinica, Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, 1991, p. 96).

Throughout the Middle Ages and up until the times of the Portuguese expansion, Cathay symbolised the ideal kingdom and society because of its tolerance and wealth even though its exact location varied over the centuries, starting off as a myth which was then transferred to China (cf. Rafaella D'Intino, op. cit., pp. XV-XXIII and XXX-XXXVIII).

18Cf. Videira Pires, op. cit., pp. 13-14.

19I have followed the line of thought presented by Roderich Ptak in his talk on "The Early Ming System and the Estado da India Compared" given in Macau on the 27th of September 1991 and later published in Review of Culture nºs 13/14, pp. 21-32.

20Apud. António da Silva Rego, A Presença de Portugal em Macau, Lx., Agência Geral das Colónias, 1946, pp. 1-2.

21J. M. Braga, "Tamão dos Portugueses" in Boletim Eclesiástico da Diocese de Macau, Macau (424), July 1939, pp. 945-957, identifies the location of Tamão as being Lin Tin Island.

In Echo Macaense (Macau 1893, p. 392) Braga refuted the opinion of Antlers Ljungstedt presented in his Historical Sketch of the Portuguese Settlements in China...: Tamão on the northwest coast of San-Shan, was a renowned harbor, to which foreign and Chinese merchants resorted for the sake of disposing of their respective investments. John de Barros and other historians designate it often by the Malay word Beneagá or Veneagá, which signifies a mart or place for mercantile business (Viking Hong Kong Publications, 1992, p. 6). Braga claimed that this opinion had misinformed many historians such as Danvers, Mayers, Morse, Colomban, J. J. More, Levy Gomes, Montalto de Jesus and even Samuel Couling who, in his Encylopaedia Sinica describes it as: the harbour on the north-west side of the island of Sancian, St. John or San Shan, the only spot where foreign trade was permitted till 1554, when Lampacau was substituted. The name is sometimes used for the whole island. (cit., p. 542).

22Chinese writers generally place the date of the founding of Macau as 1553, the 32nd year of Chia-ching (vide, for example Yuan Ban Jian and Yuan Gui Xiu, A Concise History of Macau, Hong Kong, Zhong Liu Publisher, 1988, pp. 12-15) when the Portuguese first dropped anchor in Macau. This is also the view of Tcheong-U-Lam and Ian-Kuong-Iam in Ou-Mun Kei-Leok. Monografia de Macau although Luís Gonzaga Gomes in his Portuguese translation (Macau, Tipografia Mandarim, 1979) indicates the year incorrectly as 1554 (p. 104) when the Chinese versions of the same work quoted by K. C. Fok and T'ien-Tse Chang, op. cit., p. 91 mentioned the year as 1553.

A good compilation of Chinese sources on this subject and about the ensuing debate on the strategy to be adopted with regard to the Portuguese in Macau is contained in the article by the above-mentioned K. C. Fok, "The Ming Debate on how to Accommodate the Portuguese and the Emergence of the Macao Formula", Review of Culture (13/14) cit., pp. 328-344.

23For different names such as Hoi-Kiang, Ho-Keang, Ho-Keng and in the absence of any in-depth comparative study on the different Chinese names for Macau and other places, consult José Maria Braga's extremely well documented work entitled "The Western Pioneers and Their Discovery of Hong Kong", in Boletim do Institute Português de Hong Kong, Hong Kong, (2), September 1949, pp. 7-214, particularly note 110 on p. 173 and pp. 103-104.

24Contained in Peregrinação [...] published posthumously in 1614 in which the author (c. 1510-1583) recalls his travels through the Orient from 1537-1558 which he first went to as a young man in search of his fortune.

For an in-depth understanding of the work I recommend the works of Christovam Ayres, Jordão de Freitas, Armando Cortesão, Fidelino de Figueiredo, Hernâni Cidade, Jorge Schurhammer and Costa Pimpão and particularly the Introduction to the 8th complete edition (in Portuguese) of Peregrinação (Oporto, Portucalense Editora, 1944) (I, pp. IX-LXXXVIII).

There are several versions in English, such as the translation published by Henry Coger in 1653 and re-edited in 1969, Voyages and Adventures of Fernand Mendes Pinto. Written originally by himself in the Portuguese tongue, and dedicated to the Majesty of Philip, King of Spain.... The only faithful translation, however, and one presented with abundant notes is that by Rebecca Catz, The Travels of Mendes Pinto. Fernão Mendes Pinto, (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989). Catz is also responsible for showing the lack of proof in the opinions linking Fernao Mendes Pinto to piracy (cf. "Pinto a pirate? Absurd!", Review of Culture, Macau (5), April/June 1988, pp. 65-70.

25The best Western syntheses on this subject are António da Silva Rego's book (cited in note 20) and Luis Gonzaga Gomes' later article "Teses Divergentes sobre a Origem da Cidade de Macau" in Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camóes, Macau, vol. III (2), Summer 1969, pp. 123-141.

26Cf. Graciete Batalha, "This Name, Macau..." in Review of Culture, Macau (1), April-June, 1987, pp. 7-15; Luís Gonzaga Gomes, "Diversos Nomes de Macau" in Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, Macau, vol. III (1), Spring 1969, pp. 57-72; Charles Ralph Boxer, Fidalgos no Extremo Oriente, Macau, Fundação Oriente/Museu e Centro de Estudos Marítimos de Macau, 1990, pp. 16-17 and Manuel Teixeira, Primórdios de Macau, Macau, Instituto Cultural de Macau, pp. 11-12. See also note 23.

27Similarly, during the initial stages of Portuguese settlement in Macau, the great Portuguese poet Luis de Camões who travelled in the Far East from 1553 to 1569 must have passed through Macau. His stay in Macau (according to some as a superintendent of orphans and the dead) has still not been proven and is a matter of extensive debate. Cf. F. G. Bell Aubrey, Luís de Camões, London, Univ. of Oxford, 1923 which, according to Charles Boxer (Camões e Diogo do Couto: Irmãos em Armas e nas Letras, Lx., offprint from Ocidente magazine, special issue, November 1972) was still the best study on Camões travels in Asia. Also the issue of Boletim do Instituto Luis de Camões commemorating the fourth centenary of the poet's death (Macau, vol. XIV (1/4), Spring/Winter 1980. Camões (1524/5-1580) was very learned and well-acquainted with the classics. Nevertheless, he chose to follow a career as a soldier which took him to Morocco where, after a battle, he lost the use of his right eye. He was dissolute, bohemian and unsuited to this kind of life and there are many references to uprisings and mutinies in which he was involved, often for reasons of love. Because of this, he was frequently imprisoned and exiled, both in Portugal and India. This is reflected in his work where, on a par with an undeniable lyricism, there is a bitter tension between his hopes and merit and how Fortune always succeeds in denying him the means to bring them to fruition. This tension is expressed in a masterly bucolic genre and a nostalgia for what is immaterial.

Camões is best remembered for his epic poem in the classical Greek tradition, Os Lusíadas (translated as The Lusiads by William Atkinson in Penguin, 1987), which has become a symbol of the Portuguese nation. Portugal celebrates its national day on the day of Camões' death: the 10th of June.

28Replacing the former which had been predominantly Malay and Arab, spoken by the crews who sailed the Indian Ocean.

29This was how many Portuguese words entered Oriental languages, particularly Japanese and Malay. Cf. David Lopes, A Expansão da Língua Portuguesa no Oriente durante os Séculos XVI, XVII e XVIII, Barcelos, Portugalense Editora, 1969, 2nd ed.; Luis de Matos, "O Português - Língua Franca no Oriente" in Colóquios Sobre as Províncias do Oriente, 2 (81), Lx., Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1968, pp. 11-23; J. M. Braga, "Notes on the Lingua Franca of the East" in Renascimento, Macau vol. I, April 1943, pp. 404-412.

The Instituto Cultural de Macau has also published an important foundation study in this area, written by Maria Isabel Tomás: Os Crioulos Portugueses do Oriente. Uma bibliografia, 1992.

30In other words the traffic in coolies which, after the abolition of the slave trade in the British colonies and America developed through Macau from 1851 onwards, mainly organised by foreign companies although the name of the Macanese Jose Vicente Jorge (103-1858) is connected to the initial stages (cf. the article by Manuel Teixeira"The so-called Portuguese slave trade in Macau" in Boletim do Instituto Luís de Camões, Macau, vol. X (1/2), Spring/Summer 1976, pp. 75-97).

For more on this subject, see Andrade Corvo's article "Coolie Emigration" in Review of Culture, 7/8, Oct. 88-Mar. 89, pp. 47-52.

31The Opium War is used to describe a series of conflicts between China and Great Britain lasting from 1839 to 1842 which flared up again in 1856 lasting until 1860. The signing of the Nanking Treaty on August 29th 1842 which saw the leasing of Hong Kong to Great Britain, the payment of a hefty fine and the recognition of two equal states which from thence forward would deal with each other on an equal basis, signified a critical blow to the Middle Kingdom's isolationist policy.

Its population weakened by opium addiction (traded over long decades by the British in exchange for Chinese products which had traditionally been bought with silver); its military forces defeated; forced to become an equal member of the international community, China entered into a phase of major foreign dependence from which it was freed only in the twentieth century.

32Invested in April 1846, he was assassinated by a group of Chinese on August 22nd 1849 after having attracted a great deal of hostility from the Chinese community by ordering the graves in Mong Ha district to be removed to make way for new avenues.

33Initially opened on a monthly and then a daily basis, they were not only a way of taxing and controlling the circulation of goods and peoples between Macau and China, they also prevented any territorial expansion of Macau.

34This was the name given to the political, economic, financial, administrative, judicial, military and religious power over territories, factories, fortresses or simple trading posts under Portuguese control which stretched from the Cape of Good Hope to the Far East and which, from 1505 onwards, the king of Portugal handed over to the viceroys and governors of India.

35 Governor of Macau from late 1966 to 1974 who was responsible for its construction.

*A graduate in History from Lisbon's Universidade Clássica, Tereza Sena took her MA in XIXth and XXth century Portuguese History at the same city's Universidade Nova. She has contributed many articles to historical reviews and papers and is currently Head of the Research and Studies Department in Macau's Cultural Institute.

start p. 92

end p.