Given the impossibility of covering all travellers' accounts of Macau in the space of a single article, I have opted for a personal, summarised selection of what some of these visitors wrote about Macanese women, Although there is a variety of socio-anthropological information about Portuguese women in the Far East in general, in the specific case of Macau what little data exists is often ambiguous.

Strangely enough, these accounts written by predominantly non-Portuguese travellers almost always mention the women of Macau and, more often than not in the same breath, strong criticism of their counterparts in the West (or the East, depending on the nationality of the writer).

In discussing the women of Macau there is an implicit need to look at the family and socio-cultural structures of the territory and the origins of the Macanese as a group, a source of some controversy amongst historians.

The Macanese are of Portuguese descent within a strong genetic pool. They constitute a very hybrid group, mostly due to the fact that in the early years the women who were to carry the offspring of Portuguese sailors were taken to Macau from the furthest-flung corners of the globe. These women were usually slaves who had been purchased in the well-stocked markets of the Orient. The Macanese quickly became a distinguishable group in Macau, a group which was somewhat isolated in view of endogamy and a tendency for upward mobility through marriage to Europeans.

The particular situation of women in Macau seems to have been the main reason why the Macanese as a group remained set apart and retained much of its homogeneity throughout the centuries even though now many older traditions have fallen by the wayside.

A nhonha, a lady of Macau wearing the saraçabaju (Monografia de Macau, Cheong U Lam et. al.)

A nhonha, a lady of Macau wearing the saraçabaju (Monografia de Macau, Cheong U Lam et. al.)

Most of the documents which I have examined in archives, and in particular parish records in Macau, refer to the nhons or sons of Portuguese with no mention of the daughters who were always kept as part of the group of single or married women, or else in the group of female slaves with no ethnic differentiation.

Who were the women who accompanied the first Portuguese men to Macau? What was the fate of their daughters and what was their role in Macanese society?

The answers to these questions lie in the accounts of travellers who visited Macau from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries and the letters of priests who used the territory as their gateway into China and Japan.

The most detailed descriptions must be those of the Dutchman J. H. Linschoten, the Englishman Peter Mundy and the two Chinese magistrates Cheong U Lam and Ian Kuong Iam, all of which include fascinating engravings. Other travellers also left records, some in the form of letters written from Macau1, which are also invaluable in tracing the social history of the territory. In this article, however, I shall limit myself to discussing a selection of the most important sources.

In the earliest days of Macau, the adventurous life-style of the Portuguese during their voyages in the China seas2 prevented them from taking women from their homeland with them. Moreover, there were few who would have wished to go. Nevertheless, native women, slaves and concubines accompanied these sailors on their boats as was the traditional practice in the Orient. Fernão is one of those who mentions this habit.

Naturally, children were born as a result of these early relations, boys which António Bocarro described as "stronger and lustier than any others in this East".3 This strength was most probably the result of the hybrid nature of the children's inheritance and natural selection through infant mortality. Bocarro makes no mention of the daughters although they had already been discussed by Fernão Mendes Pinto when he described Liampo. 4

Fernão Mendes Pinto described a banquet given by the residents of the city in the following manner:

seated at the table they were served by very beautiful girls, richly dressed in the style of the Mandarins. For each delicacy which was brought to the table, they sang to the accompaniment of instruments which others played5, and António de Faria was served by eight girls, all of them gentlewomen, the daughters of honourable merchants who had been brought by their parents out of respect for Mateus de Brito and Tristão de Gâ. All of them were dressed as mermaids...

It is worth noting that Fernão Mendes Pinto describes the daughters of the Portuguese as "dressed like mermaids". This must be a reference to the Asian woman's saraça baju which had made its way from India through Malacca into Southeast China. This dress consisted of a skirt and a fine bodice which Linschoten, writing in the late sixteenth century (1593-95)6 also mentions in his description of the Portuguese in Goa.

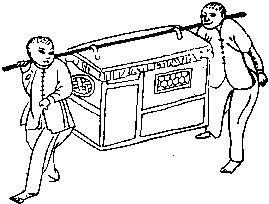

Litter for transporting a nhonhonha (op. cit., idem)

Litter for transporting a nhonhonha (op. cit., idem)

According to Linschoten: the wives of the Portuguese, Mestiços and Indian Christians are never seen, but spend the greater part of their time in domestic seclusion and only leave their homes to go to church or to visit... on which occasions they are carried in covered palanquins.

At home most of them leave their head uncovered while the upper part of their body down to their hips is concealed in a blouse of light, fine cloth which they call "baiu". Their forehead is covered by a folded cloth richly embroidered. They wear flat shoes.

This is the costume which the wives of the Portuguese founders of Macau took with them to the city.

Writing in the seventeenth century, Peter Mundy7 also described the clothing worn in Macau, including that of the Macanese women and the kimonos which the children of wealthy families used, with special reference to the precious jewels and costly decorations that were seen.

This place affoards very Many ritche Men, Cladde after the Portugall Manner. Their Weomen like to those att Goa in Sherazzees or [? and] lunghees, one over their head and other aboutt their Middle Downe to their Feete, on which they were low Chappines. This is the Ordinay habitt of the weomen of Macao. Only the better sort are carried in hand Chaires like the Sidans att London, all close covered, off which there are very Costly and ritche broughtt From Japan. Butt when they goe without itt, the Mistris is hardly knowne From the Maide or slave wenche by outtward appearance, all close covered over, butt that their Sherazzees or [? shawls are] finer.

The saide weomen when they are within Doores wear over all a Certaine large wide sleeved vest called Japan kamaones or kerimaones because it is the ordinary garment worne by Japaneses, there beeing Many Dainty ones broughtt From thence off Died silke and of others as Costly Made here by the Chinois off Ritche embrodery off coulloured silk and golde.

This kimono was probably the quimao or bajú worn by women in wealthy Macanese families perhaps when they were receiving guests in their homes. These garments were made of expensive heavy cloth and richly decorated.

Whenever they went out, the women were shut up in sedan chairs and further enveloped in their veils which is reflected in the drawings of Peter Mundy.

Compared to Peter Mundy's description of Macau, the account of the French doctor Dellon (Mundy's contemporary) concerning women's clothing in Goa indicates that the old bajus of Islamic influence were common in India while in Macau the wives of wealthier merchants preferred the Japanese or Chinese kimono. This was what gave rise to the cabaia baju which was still in use in the early years of this century.

During the eighteenth century, Macau's economic position was weakened and many men left the city, some of them taking their families with them while others abandoned them. At the same time, there was an influx of less scrupulous adventurers, many of whom had fled from Goa. With their arrival, the city sank, hand in hand with its failing fortunes, into a moral quagmire.

Sir Alexander Hamilton8, noted in the early eighteenth century that: In the city there reside some two hundred men and around fifteen hundred women, many of whom are prodigious in their ability to procreate without husbands.

Other travellers who came looking for Macau during the same century such as the sailor Nicolau Fernandes da Fonseca (1774) made the same harsh criticisms.

The Chinese magistrates Cheong U Lam and Ian Kuong Iam who came to Macau and stayed for some time during the eighteenth century, recorded their impressions in a fascinating book with lavishly detailed engravings of Portuguese types. 9 Of particular note amongst these engravings is one of a nhonha whose exotic clothing caught their attention. Their own description of this style of clothing matches up perfectly with that of Peter Mundy who also left a drawing of it in his own book.

The magistrates left a host of notes on the habits and customs of the Portuguese in Macau: The men and women of rich birth sit and eat [indicative of lives of leisure]. The poor ones are soldiers or sailors who are employed on boats. The women embroider handkerchiefs and make cakes and sweets to sustain their lives.

The descriptions of these Chinese visitors carries on in the same vein expressing admiration at the luxuries and extravagance of the Portuguese who, like Asian lords, still went out in sedan chairs and litters or on foot or horseback but always escorted by slaves bearing parasols: The women had the same habit, accompanied by slaves and almost all of them dressed in the same manner with the only difference between their clothing lying in the quality of the cloth.

Cheong U Lam and Ian Kuong Iam also noted that the men were not allowed to keep more than one wife in their home for fear she would complain to the Bishop causing certain punishment. They were referring, obviously, to the prohibition of bigamy. This reflects their entirely Sinocentric point of view, as wealthy Chinese men were able to keep several wives, living harmoniously under one roof although it was only the first who enjoyed the perks of being the head of the household and mother of all the children regardless of which wife might have been the natural mother. Confucionist morality, however, ordained that marriage should be monogamous and that the woman should be absolutely faithful to her husband. Thus the magistrates' shock at "Portuguese women not being forbidden from having other men". This may well have occurred due to the economic and moral collapse of the city which had reached such depths that it was not uncommon for the heads of families to offer their own wives and daughters to foreigners in return for some financial gain.

From the preceding discussion and examples we can draw some conclusions about the Macanese woman and society in Macau between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries.

1 The clothes worn by men changed according to European fashions while those worn by women remained largely the same for two centuries and differed from those used by European women in the period. This leads one to suppose that most, if not all, of the women in Macau were of Aisan or Euro-Asian descent.

2 These women led leisurely lives if they were members of the upper classes and all classes were marked with strong Oriental overtones.

3 The women of less well-off families busied themselves with sewing work producing mutri and escarrachada and making sweets and "confectionary".10

4 The Oriental mentality meant that many of the Euro-Asian women viewed the mores of Europe's bourgeoisie with contempt although their own Portuguese husbands were regarded as jealous and brutal.

5 In the mid-seventeenth century, when the city was suffering from the interruption of trade with Japan, many men left Macau, some of them leaving behind their families. These women sank into poverty and some as low as the oldest profession in the world which was the state in which many eighteenth-century visitors to the territory found them.

Women of Macau (drawing by Peter Mundy)

Nevertheless, we must interpret human misery in terms of material poverty. The manner in which these women were abandoned, and the harem mentality was a common feature of the Portuguese in those cities they inhabited in the Far East.

6 The disdain with which manual work was viewed by both sexes in more comfortable surroundings can, on the other hand, be seen as a reflection of the European mentality as it had developed from the Middle Ages when it was considered beneath noblemen for them to work, a humiliation and even condemnation. It was far more acceptable to be seen begging for alms that to work with one's own hands.

Confronted with these autochthonous communities, the Portuguese and those of mixed blood were unwilling to lose pride in their own language, retaining their preoccupation with their lineage11 which Bocage, who travelled throughout the Orient, satirised:

"... Mas a tua peor epidemia

O Mal que em todos dá que produz flatos

É a van, negregada senhoria."12

By the mid-nineteenth century liberal ideas from Portugal were encroaching on her overseas possessions. This, combined with the Victorian ethics of neighbouring Hong Kong, provided Macanese society with different moral concerns. Family morals which had been contemplated with utter disdain in previous centuries were once again adopted as essential in the upper classes, a move reinforced by the abolition of slavery in 1876. What had once been large families, synonymous with periods of bourgeois expansion, became smaller. Now that the dowry had also been abolished, Macanese girls enjoyed a higher degree of independance, particularly with regard to marriage. This was certainly the view of José Ignácio de Andrade in his Cartas escritas da India e da China nos anos de 1815 a 1835.13

Once the steam and packet boat routes had been set up, more European women set sail eastward in search of adventures and Macau. The rivalry between them and the Macanese women has, paradoxically, grown up to this day with the arrival of ever greater numbers of Europeans of both sexes in search of easy money.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ANDRADE, José Ignácio de (1847): Cartas escritas da India e da China nos anos de 1815 a 1835, 2 vols. Lisbon.

ARAGO, G. (1822): Promenade autour du Monde 1817-1820, 2 vols. Paris.

ARNOSO, Conde de (1816): Jornadas pelo Mundo, Oporto: Companhia Portuguesa Editora.

BARBOSA, Duarte (1813): O Livro de Duarte Barbosa--Livro em que dá relação do que viu e ouviu no Oriente, Lisbon: Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias.

BARROW, John (1804): Travels in China, London

BENYOWSKY, Mauritius Augustus (1789): The memoirs and travels of... translated from the Original Manuscript, 2 vols. Printed for G. G. J. and J. Robinson, Pater Noster Row. (There are other editions in French, German and Polish.)

BOCARRO, António (1635): Livro de todas as Fortalezas da India... ,Evora Library and District Archives, Cod. CXV-2-1.

--(1876): Década XII da História da India Compilada por António Bocarro, Lisbon: Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencias.

BONTEKOE, Willem Ysbrantz (1929): Memorable description of the East Indian Voyage 1618-26, London, George Routledge & Sons Ltd.

CAMOES, Luís de (1942): "Cartas" --Obra Completa de Luís de Camões, Lisbon.

CALDEIRA, Carlos José (1852): Apontamentos duma Viagem de Lisboa à China e da China a Lisboa, Lisbon.

CARERI, Gemelli de (1699-1700): Giro del Mondo, Naples: Stamperia di Guiseppe Roselli.

CARTERET, P. (1774): Voyage (1766-1769), 2 vols., Paris.

CHEONG U Lam and IAN, Luong Iam (1950): Monografia de Macau, trans. Luís Gonzaga Gomes, Macau: Imprensa Nacional.

COOK, James (1785): Troisième voyage de Cook..., trans. M. D., Paris: Hotel de Thon.

DELLON, M. (1685): Relation d'un voyage faite aux Indes Orientales, Paris.

DIAZ ARENAS, Rafael (1839): Viaje curioso e instructivo de Manila à Cadiz por China, Batavia, el Brasil y Portugal..., Cadiz: Imprenta de D. D. Ferós.

FONSECA, Nicolau Fernandes da: Diário de viagem-1774, quoted by Manuel Teixeira in Macau no Século XVIII, Macau: Imprensa Oficial.

FROGER, S. Francois (1926): Relation du premier voyage de français à la Chine... (1698,1699 e 1700), Leipzig.

GROSE, J. H. (1758): Voyage aux Indes Orientales..., trans. from English original, London.

DE GUIGNES, Charles Louis Joseph (1808): Voyage à Peking, Manille (...) dans l'intervale des années 1784-1801, 3 vols., Paris: Imprimerie Impériale.

HOUCKGEEST, A. E. van Braan (1798): Voyage de l'Ambassade de la Compagnie des Indes Orientales Hollandaises vers l'Empereur de la Chine dans les années 1794 & 1795, vol. 11, Philadelphia.

HAMILTON, Alexander (1727): A New Account of the East India, London.

HUBNER, Baron de (1877): Promenade autour du Monde (1871), Paris: Hachette.

LANGSDORFF (1813): Voyages and travels in various parts of the World, 2 vols., London.

LAPLACE (1833): Voyage autour du Monde (1830-1832), Paris.

LAVAL, F. Pyrard de (1944): Viagem de Francisco Pyard de Laval (1601-1611), Portuguese version corrected and annoted by Joaquim Heliodoro da Cunha Rivara, Oporto: Livraria Civilização.

LOBO, Jerónimo (1965): "O Itinerário do Pe. Jerónimo Lobo por M. Gonçalves da Costa" in Portugal em Africa, vol. 22, pp. 141-145, Lisbon.

LINSCHOTEN, J. H. de (1610): Histoire de la navigation de Jean Hugues de Linschoot [sic] Hollondais: Aux Indes Orientales, trans. from the French, Amsterdam.

MACARTNEY, (1804): Voyage dans l'lnterieur de la Chine et en Tartarie --1792,1793 et 1794, 5 vols., Paris.

MARIA, José de Jesus (1940): Azia Sinica e Japonica (1745), pub. and annotated by C. R. Boxer, vol. 11 pp. 230-32, Macau.

MELLO, Custódio de (1896): Vinte e um mezes ao redor do Planeta, Rio de Janeiro.

MOQUET, Jean (1830): Voyages, Paris.

MUNDY, Peter (1919): The Travels of Peter Mundy (1658-1667), 5 vols., ed. Sir R. C. Temple and Miss L. Anstey, London: Hakluyt Society.

NAVERY, R. de (1880): Les Voyages de Camoens, Paris.

--(1841): Nouvelle Bibliothèque des Voyages Anciens et Modernes centenant la Relation Complète ou analysèe eds voyages de Cristophe Colomb, Fernand Cortez, Pizarre, Anson, Byron..., 12 vols., Paris: Chez Duménil Editeur.

OPISSO, Alfredo (1898): A India, Barcelos.

PERCIVAL, Robert (1803): Voyage à l'Ile de Ceylan fait dans lew années 1797 à 1800, 2 vols., Paris.

PEREIRA, A. Feliciano Marques (1863): Viagemda Corveta D. João I à Capital do Japão no anno de 1860, Lisbon.

PINTO, Femão Mendes Pinto (1678): PeregrinaÇam de Fernam Mendez Pinto, Lisbon.

PRÉVOST (1790): Histoire générale des voyages, vols. 1, 5, 6, 9 and 11, Paris.

ROQUEFEUIL, Camille (1823): A voyage round the World between the years 1816-1819, London.

SCHERZER, Karl van (1861-63): Narrative..., 3 vols., London.

SOUSA, Francisco de (1710): Oriente Conquistado..., Lisbon.

STAUNTON, George (1792): An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China, London.

TAVERNIER, Jean Baptiste (1712): Les Six Voyages de... Qu'il a fait en Turquie, en Perse et aux Indes; pendant l'espace de quarante ans..., Paris.

TOWNSEND, Ebenezer (1797-1799): The Original Diary of Mr Ebenezer Townsend Jr. while on board the Supercargo of the 'Neptune', n. p.

NOTES

1Only those writers who are particularly relevant to the period in question are mentioned, which has meant that a great many writers commenting on features of life in Macau during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have been omitted.

2Peregrinaçam de Fernam Mendez Pinto, Chapter 70, p. 97.

3A. Bocarro: Livro de todas as Fortalezas da India..., Évora Library and District Archives, Cod. CXV-2-1.

4Peregrinaçam de Fernam Mendez Pinto, Chapter 70, p. 97.

5These may have been Chinese slaves or simply pei-patchai, the traditional entertainers at Chinese banquets who may have been brought from Ning-Po.

6Jean Linschoten: Histoire de la navigation de Jean Hugues de Linschoot [sic] Hollondais: Aux Indes Orientales, trans, from the French, Amsterdam, pp. 84 and 85.

7Peter Mundy: The Travels of Peter Mundy (1658-1667), 5 vols., ed. Sir R. C. Temple and Miss L. Anstey, London: Hakluyt Society, vol. 3 pp. 159 and 316 (a description of Macau in 1637). Peter Mundy arrived in Macau on July 5 1635 and returned to England in January 1638 (Manuel Teixeira: Macau através dos Séculos, Macau: Imprensa Nacional, 1977.

8Alexander Hamilton: A New Account of the East India, London.

9Cheong U Lam and Ian, Luong Iam: Monografia de Macau, trans. Luís Gonzaga Gomes, Macau: Imprensa Nacional.

10These consisted of embroidery, whitework and bead work, mutri referring to beads and escarrachada referring to sequins and gold thread.

11Many commoners were given noble titles and other honours for having served the king. In the case of Macau, these services could consist of hefty donations and not military valour.

12Referring to the mestiços of Goa. Bocage, Poesias, Lisbon 1943, p. 319.

13José Ignácio de Andrade: Cartas escritas da India e da China nos anos de 1815 a 1835, vol. 2, p. 2.

*Ph. D. (Lisbon); lecturer of Anthropology in the Institute of Social and Political Sciences; researcher attached to the Centre for Oriental Studies of the Orient Foundation; author of a wide range of publications dealing primarily with ethnography in Macau.

start p. 77

end p.