In one of his many self-portraits, Chinnery offers this unusual angle of himself in middle age.

In one of his many self-portraits, Chinnery offers this unusual angle of himself in middle age.

Exile: for some the kiss of death; for others a new lease of life.

George Chinnery was a British artist who sailed into Macau in 1825. He was at the height of his artistic career, aged 51, and had turned his back on the chances of ever rising higher in public esteem in his own country.

His contemporaries basked in the benevolent climate of post Regency England.

Following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, England's standing in the world was probably at its highest point as the United States of America grappled with the aftermath of the revolution and France sought to regain its composure after its flirtation with imperial adventures in Europe and Russia.

Into the powdered, pampered salons of London, Britain's aristocracy followed the follies of its happy-go-lucky Prince Regent in an orgy of high living and free spending from which the circle of favoured artists prospered with many others who catered to their whims.

Chinnery would undoubtedly have won a share of the commissions and with a modicum of self-discipline he could have challenged the artistic establishment of the day to undertake some of the major portraits of that time.

He had begun his career in London with great promise in the 1790s, moved to Ireland where he was active both as a portraitist and a teacher, winning many accolades. He had then travelled to India in 1802 in search of new experiences and to exploit family connections to gain new commissions. Life was good and the high and mighty of the land flocked to his studio, though more often he to their stately homes, surrounded by opulence and luxury.

But any chance of returning to England from India was thrown to the winds when Chinnery broke down under the strain of marital tensions and a family breakdown, an extra-maritial affair which produced two children, the death of his much-loved son, combined with a failure to complete several assignments that had come his way in his final years in British India.

Hounded by debt collectors, unable to live with his much maligned wife, harassed by clients demanding completion of portraits, Chinnery cracked under the pressures and fled the country and the judicial reach of the East India Company's authority in India.

In 1825, he took a ship heading east, testing the waters no doubt at Penang, Malacca and Singapore, before heading for the intriguing port of Macau where a benevolent Portuguese rule prevailed and offered a haven for businessmen of many countries trading with China.

He travelled on the 1,425-ton Hythe, commanded by Captain J. Wilson, and owned by the President of the Select Committee of the East India Company in China, Mr Charles Marjoribanks. Chinnery travelled with an Indian servant and if he did any painting or sketching en route none is known to have survived.

He was a notoriously bad sailor anyway and in his depressed state of mind he would have had little inclination to have taken out his sketchbook to record the many exotic scenes he saw.

Conscious of the persistence of debt-collectors wherever the writ of the East India Company's authority ran, Chinnery quickly realised there was no security in the Straits Settlements of Malaya, being subordinate to rule from India. Singapore had been founded only a few years earlier by Sir Stamford Raffles and as yet offered few of the creature comforts a pampered Chinnery would have demanded. Macau alone offered the refuge he sought.

Furthermore, Macau had everything he could ask for -- an established city with most of the comforts he needed, a small expatriate English-speaking community with whom he could socialise, an abundant scope for his artistic talents for Macau and its environs were not only picturesque but were endowed with an exotic diversity of life.

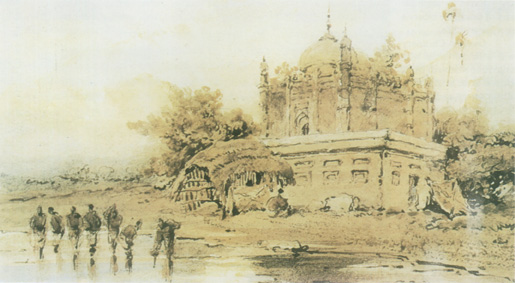

Chinnery travelled extensively in India on foot and by river always busily sketching the passing scene. The above is a watercolour from one of his many expeditions to the interior.

Chinnery travelled extensively in India on foot and by river always busily sketching the passing scene. The above is a watercolour from one of his many expeditions to the interior.

Long before setting foot there, Chinnery had heard of Macau while spending a short vacation with the missionary, Dr Joshua Marshman, in Serampore, India. Far from being the back of beyond, it enjoyed regular contacts with seafarers and travellers from many parts of the world, and was an increasingly important hub of trade between China and the West.

China indeed had been a regular stop on the trade routes for more than a century and Portuguese Macau was the one foothold which Europeans were allowed to live in. During the trading season, when the northerly monsoon blew, they were permitted to occupy their offices in nearby Canton to conduct trade. Then they returned to Macau for the summer where most maintained large and lavish homes.

The wealth there was considerable; a small elite of Chinese middlemen known as the Co-Hong were alone permitted to deal with the Europeans. Traders from America, Britain, Sweden, Spain, and other parts of Europe were well established there and maintained a lifestyle almost regal in its splendour.

But if Chinnery envisaged rich pickings, he himself was very dependent on a few wealthy patrons, particularly among the British community in Macau. Far from queuing up at his door to have their portraits painted, they were for the most part shrewd and calculating men, initially a little suspicious of the newcomer and in that small community well aware of his reputation in India as a fitful artist and an absconding debtor. The newspapers from Calcutta were as avidly read in Macau as later generations would thirst for The Times of London.

A gregarious, affable and sociable man, however, Chinnery gradually built contacts and allayed suspicions. He lodged with one British family for a short period after his arrival before setting up his own studio. But to begin with, his studio was the streets of Macau. He would perch himself on a wall or set up a seat beneath the shade of a Banyan tree and sketch people and places with a verve and fluency that evoked curiosity, interest and ultimately appreciation.

Slowly, the invitations began arriving, at first to breakfast from early morning walkers who stopped to glance over his shoulder. His ability was unquestioned and his hosts soon discovered his ability was phenomenal. Breakfast in these days was never the niggardly slice of toast and porridge but a sumptuous affair, often rice and curried meat, washed down with cups of tea, fruit and other local delicacies.

Macau in 1825 had a small population. The Portuguese establishment presided over a mixed society which could not have numbered more than a few thousand; early maps show the outlines of a network of streets in the centre of the city; many of the major buildings of that time survive to this day.

Chinnery's drawings show the concentration of buildings lining the bay on what is today the Pray a Grande. Before the sea wall, there was at one end a small area of beach on which fishermen would land their catch. Vistors, such as Miss Harriet Low from Boston, Massachusetts, testify to the large numbers who lived on boats and who made their livelihood from the sea as fishermen or ferrymen. They either lived aboard their boats or pulled them ashore and built shelters around them.

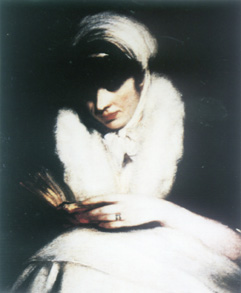

Harriet Low, a young American visitor to Macau during Chinnery's residence in the city, poses for what is widely regarded as one of his most attractive portraits in oils.

Harriet Low, a young American visitor to Macau during Chinnery's residence in the city, poses for what is widely regarded as one of his most attractive portraits in oils.

In the foreign community, which included British merchants, most employed by the East India Company, and some private traders of various nationalities, there were 74 listed, of whom about half were Parsees. Many had wives and families. The diversity of their activities ensured employment for many hundreds of people, some as personal servants, commercial employees, boatmen, tea and silk buyers, silver dealers, compradors and others. Nearby, at Lintin Island, the opium traffic was a major enterprise in which many of the Macau-based merchants were engaged.

Marianne Chinnery, in her early days in Ireland, wearing a wedding ring and reading a book, sits for her husband, a study in contemplation.

Marianne Chinnery, in her early days in Ireland, wearing a wedding ring and reading a book, sits for her husband, a study in contemplation.

Never, it seems, was Chinnery attracted to a life of commerce. The prospect of making a few dollars on the side, much as a contemporary might make it on the stock exchange or through property speculation, may have occurred to Chinnery but not only was he limited in his means, with little access to credit, but he was obliged to remit money to support his wife and to pay his debts in India; this he did through his friends at Magniac & Co, William Jardine and James Matheson, who were also among his early patrons. This left him little or nothing to risk on commercial deals and he needed everything to keep body and soul together and to ensure a supply of paints, canvas, pencils, ink and paper.

We get some idea of the life Chinnery led from the drawings which survive his residence in Macau. In London's Victoria and Albert Museum there are seven large scrapbooks with more than 1,200 sheets containing about 10,000 drawings; this is just one of a number of collections which survive.

These were the drawings which Chinnery could not bear to throw away. He kept them all in several camphor wood trunks which were found after his death and sold by order of the Macau court to meet his debts.

An auction was held of his possessions and though the details were not known, it can be assumed that his paintings fetched good prices, but his drawings (which today sell for $5,000 to $50,000 each) were passed in at "firesale" prices probably by the trunk-load.

His landlords, the Catholic Mission of Peking, recovered outstanding rents from his estate. Others with claims probably included compradors, food suppliers and victuallers, tailors and tradesmen.

Some of these drawings came into the possession of James Orange, a leading architect in Hong Kong, and one of the founders of the firm of Leigh & Orange. He was also instrumental in acquiring the significant collection of China coast art (including Chinnery paintings and sketches) from a former Chinese Maritime Customs Officer, Mr Wyndham O. Law. This was bought by Sir Paul Chater, and is today in the possession of the Hong Kong Museum of History.

There are other major collections in the archives of the Hong Kong & Shanghai Bank where apart from the biggest and best collection of paintings and water colours there are several albums of drawings; another is in the Toyo Bunko in Tokyo, formerly belonging to Dr G. E. Morrison of Peking, the London Times correspondent there. Another large collection exists in the Geographical Society of Lisbon (and was exhibited in Macau in 1985), and another at the Birmingham Art Gallery in the United Kingdom.

Several Hong Kong residents have built up significant collections bought at auction in recent years.

Most of the drawings in the Victoria and Albert collection are dated at least with the year and some with days and months, coupled with notes in Gurney shorthand; some are even signed with initials or, rarely, with his full name. Most have been drawn with a pencil but quite a few are in ink.

The drawings show how Chinnery lived out his days in the heat, humidity and the often cold and windy weather that Macau, Canton and Hong Kong experienced -- for once he moved to Macau, these were the only other areas the visited. Missionaries and diplomats ventured to Peking but businessmen were confined to Macau at least until after the Opium War and the opening of the so-called Treaty Ports from which deregulated trade was permitted between Chinese and foreigners.

Chinnery sketched with a determination and discipline that evokes admiration. There were times when he suffered from boils or other minor ailments when he put aside his sketchbook. There are indications that he was a hypochondriac but he was no drinker and while he may have smoked opium there is no evidence that he was more than an occasional user. His peccadilloes therefore do not appear to have contributed to his health problems.

On the other hand, he was a glutton, by his own admission eating enormous quantities of food whenever possible, yet the doctor who conducted his autopsy after his death found his stomach "wonderfully healthy". In fact he died of a stroke at the age of 78.

But even in his old age there can be found drawings and paintings dated in these years and his visit to Hong Kong at the age of 72 in 1846 produced a number of remarkable sketches and paintings --mainly water colours -- for a number of customers who had moved from Macau following the establishment of the British colony in 1841.

Chinnery, however, hated the summer heat of Hong Kong -- something he never complained about in Macau or Canton. He also found it a dusty, insect-infested, noisy place with an incessant sound of hammering, despite the comfortable quarters of Jardine, Matheson at East Point. Nor was the sea journey across the Pearl River estuary much to his liking, a lorcha taking up to 12 hours in those days.

Chinnery was not a good sailor at the best of times; having travelled half-way around the world there are no scenes of shipboard life, rigging, masts, billowing sails, deck activities that attest to his seamanship and we can only assume that he spent his time at sea as a landlubber lying down below decks.

In spite of this, Chinnery sketched and painted thousands of junks and Indian river craft and there is a landscape of a pagoda on the banks of the Pearl River, and many of river-side temples in India, which could only have been sketched from the deck of a passing vessel. Given the choice of a river boat and a horse or bullock-drawn cart along bumpy village paths Chinnery knew the lesser of two evils.

He was not just a hypochondriac who probably was prone to seasickness, but always apt to exaggerate. He was a notorious story-teller and an amusing raconteur who half-believed some of his fantasies. In these stories he could be hero or villain-but more often the former.

He feigned (but probably also felt) a fear that his wife might track him down and took elaborate steps to avoid contact with her, even on one occasion rushing upriver to Canton to avoid her reported arrival in Macau; the truth was she was nowhere near Macau, having returned to England from India.

Ungraciously he also ridiculed her "ugliness". Yet in her youth she was demure and attractive, as Chinnery's portrait of her shows. If anyone was ugly in later life it was Chinnery himself who was described by one of his sitters (Miss Harriet Low) as "one of the ugliest men in existence."

Yet in spite of this he was ever a ladies' man, dashing, reckless, witty and undoubtedly capable of great charm and courtesy -- even if his achievements fell short of his aspirations.

Of his abilities as an artist, Chinnery was convinced that he was numbered among Britain's top five, an illusion he carried with him after more than a quarter of a century away from the wider world of art and artists. For while he continued to send some of his outstanding paintings to be exhibited at the Royal Academy, he had no way of knowing the quality of his British or European competitors.

While at one time an artist of great promise, having studied under Sir Joshua Reynolds, Chinnery cut himself off from the influences and opportunities that might have won him acclaim with men like Sir Thomas Lawrence and J. M. W. Turner.

Chinnery strove to maintain his standards but in exile he remained largely a traditionalist and he lacked the competitive edge to aspire to greater heights. His most serious opposition came from a talented Chinese painter named Lamqua or Guan Qiaochang, active in Macau and Canton, who while always able to undercut him in price was not comparable in technique or experience.

Chinnery may have nurtured a hope that he might return to the London scene one day but as he moved through his sixth decade he realised how temperamentally unsuited he was to the hurly-burly of a busy city, how difficult it would be to cope with life, keep his wife at arm's length, and maintain a lifestyle comparable with that enjoyed in Macau. And, perish the thought, the idea of three months at sea put paid to any notion of ending his exile.

Happily for Macau he never tired of the subject and the quality of draftsmanship never flagged. One scene that he painted endlessly was the beautiful Bay of Macau, in all its moods. But he put just as much skill into a pencil or ink sketch of a church or temple, a group of street gamblers, or a blacksmith at work, a pig grovelling in the mud, a cat lapping a saucer of milk or a dog scratching its ear. But whether it was a village hovel or a stately mansion, no city has been sketched in such detail by a leading artist as Macau was during Chinnery's 27 years there.

Most of the sketches bear descriptions prepared by the Victoria and Albert Museum. In some cases Chinnery left an index for his albums but in others he wrote shorthand notes on his drawings; otherwise they were identified by contemporary experts. Thus there are drawings of subjects such as "Steps near the Franciscan Church", "Part of the Great Joss House", and "Architectural details of the Church of St Domingo". There are numerous street scenes outside the same church, usually filled with hawkers, much as it is today. There is another entitled "Scene in Macau with the Misericordia Church to the right". Another is entitled "Village at the foot of the hill below the College of San José, Macau". Another is entitled "Governor's House and Pedro Fort, Macau".

Self-portrait of the artist as he sits in front of his canvas.

Other buildings described are "Part of the Citadel and Franciscan Fort, with part of Mr Whiteman's house ('the 40-pillared house')" and "Large archway in the centre nave of St Paul's Church, Macau, after it was burnt (December, 1835)". Another was "Mr Barreto's house, Macau" and "Misericordia Church and Senate House". Yet another was "The Rev. Mr Vatchell's house (formerly Mr Thornhill's)". The Rev George Harvey Vatchell was the Chaplain to the East India Company's factory in Canton, while Mr Thornhill was one of the Company's writers. Mr John C. Whiteman was the senior partner of the firm of Whiteman & Co in the 1830s, dealing in cotton yam and calico amongst other goods.

It is interesting to note that Mr Whiteman was the subject of a diplomatic incident between the British, Portuguese and Chinese authorities. Having established his firm in 1830 and having no house in Macau he and his wife resided in the factories in Canton.

When finally they left on February 1, 1831, Whiteman rented a house from the San José College. At first the Governor of the day, Snr João Cabral de Estifique, gave his permission to the arrangement. The next day he withdrew it on the grounds that "the most explicit instructions had been received from Lisbon to prevent the residence of private British merchants in Macau, since the interference of British merchants had been destructive to the prosperity of Macau".

Whiteman appealed and the President of the Select Committee of the EIC, Mr Charles Marjoribanks, met the Governor the next day but he refused to change the order.

The allusion to the "interference of British merchants which had been destructive to the prosperity of Macau" apparently referred to the Chinese pressure on the Macau administration to stamp out the opium trade. British merchants, however, had build up such a big business that they were unwilling to forfeit it and transferred their operations to the island of Lintin, near the southern tip of Lantao, where it flourished for many years.

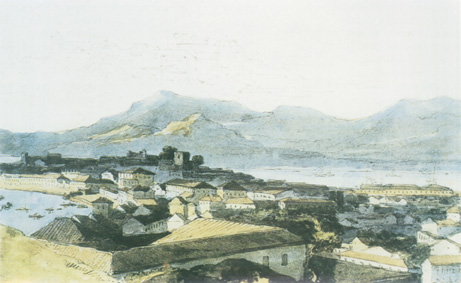

A water-colour of the peninsula and township of Macau, with Lappa Island in the background.

The outcome of the dispute over Whiteman's house is not known. He was still in business two years later and Chinnery was still describing the 40-pillared-house rented from San José College as Whiteman's. His name, however, disappeared from the records of the East India Company in later years, without explanation.

Another sketch to appear in the Victoria and Albert collection is of "Dr Colledge's original hospital in Macau" dated 1829. Thomas Richardson Colledge had arrived two years earlier as assistant surgeon to the EIC factory. He was then 31 and his salary was £1,000 a year. One of his first acts was to open a free clinic devoting himself mainly to eye diseases. Harriet Low wrote in her diary: "Everybody loves him and speaks well of him."

Street scene showing people at their daily tasks in the centre of the city with Monte Fortress in the background.

Although Harriet Low showered her warmest sentiments on him, she confined them to the privacy of her diary and in 1831 the handsome young doctor fell in love with Harriet's bosom friend, Caroline Matilda Shillaber, then on a visit to Macau. Chinnery painted both of them, one showing a young Chinese lad kneeling and holding up a letter of thanks to the doctor for restoring the sight of an aged parent. When asked whether the young Chinese boy shown in the painting had managed to keep still during the sittings for the portrait, Chinnery quipped: "The rock of Gibraltar is calf's foot jelly compared to him."

Sadly, three of the Colledge's children died in Macau and are buried in the old Protestant Cemetery next to Camõens Garden. In 1837, Colledge founded the Medical Missionary Society in China and continued to be President until his death in 1879. He also became a Fellow of the Royal Society and a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons.

Another of Chinnery's illustrations of 1831 is entitled "The Casa, in the gardens of which is Camõens' Cave (the residence of Lady Pereira)", while another, dated 1826, is of the house in Canton of the wealthy Chinese Hong merchant, Chinqua, whose retirement in 1827 and the sale of his grossly overvalued firm to another Hong Merchant, created a crisis in Sino-Western trade.

There are also drawings by some of Chinnery's pupils, including some by Harriet Daniell, of various Macau scenes. Chinnery supplemented his income by giving lessons to several European and Portuguese residents, including Marciano Baptista, the celebrated local artist.

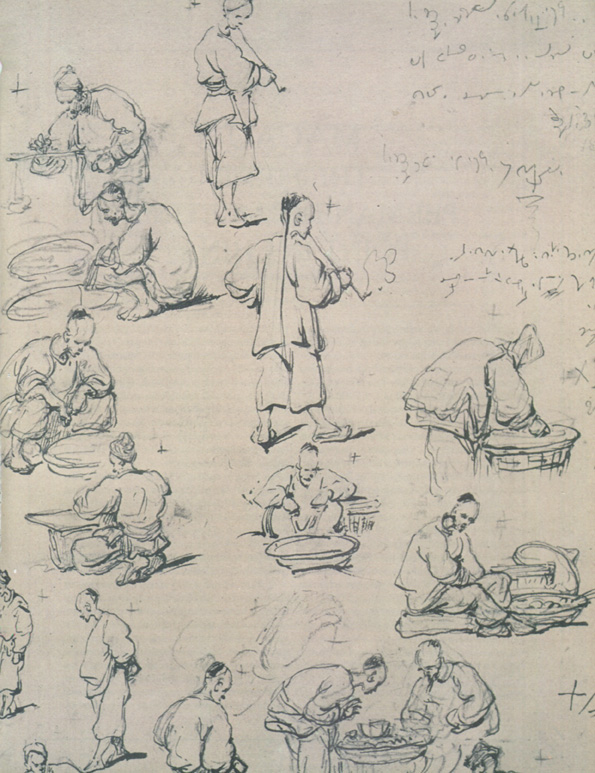

By far the largest number of sketches are of the people of Macau in their daily lives, covering almost every activity. Many of these were later turned into water-colours or oil paintings and they provide a kaleidoscope of the local scene in all its variety.

They date from a few months after his arrival in Macau to a few years before his death in 1852, though drawings in other collections show he was still active in his 78th year. However, a surviving letter written shortly before his death tells of increasing ill-health --"the confusion and the swimming in the head I the most complain of." In spite of this he had his palette set in case he was able to use it.

He passed away on May 30, 1852, having enjoyed a rich, full and busy life even if his artistic ambitions fell some way short of the expectations entertained in earlier years.

South China nevertheless is much the richer for his presence and Macau benefited most of all in the illustrative record that survives -- alas today mainly in foreign archives. Chinnery, exile though he was, was no Gauguin, and his paintings, while deservedly popular and rising in value, are of more historic than artistic importance. Here was the Macau of old, Canton in the heyday of the China trade and Hong Kong in its infancy -- a world so changed.

Sketches of Chinese engaged in a variety of activities.

*Robin Hutcheon was born in Shanghai. He lived for over thirty years in Hong Kong working, for almost two decades, as the Editor of the South China Morning Post. He has published five books including the biography of the French artist Auguste Borget.

start p. 83

end p.