14 states that the pains of the world open the way for the intelligent man to search out refined pleasures such as "delicate food, the use of tobacco and opium, spiritual liquors". In his Macau home, the poet had a daily encounter with the "divine drug". There is little to be gained in looking to miserable descriptions or pious sentiments, false morality or a mediocre fear of degeneration. Camilo sheltered from the world but this does not mean he forgot it. Quite the opposite, he remained attentive yet cocooned against the pain, his spirit enveloped in the spiralling sweet smoke, far-removed from human ills beholding only the calm immenseness of his wisdom.

</figcaption></figure>

<p>

In order to avoid any misunderstandings, let us turn to somebody who really knew the subject:

</p>

<p>

<i>For it seemed to me as if then first I stood at a distance, and aloof from the uproar of life; as if the tumult, the fever, and the strife, were suspended; a respite granted from the secret burthens of the heart; a Sabbath of repose; a resting from human labours. Here were the hopes which blossom in the paths of life, reconciled with the peace which is in the grave; motions of the intellect as unwearied as the heavens, yet for all anxieties a halcyon calm: a tranquillity that seemed no product of inertia, but as if resulting from mighty and equal antagonisms; infinite activities, infinite repose. </i>

</p>

<p>

<i>Oh! just, subtle, and mighty opium! that to the hearts of poor an rich alike, for the wounds that will never heal, and for "the pangs that tempt the spirit to rebel," bringest an assuaging balm; eloquent opium! that with thy potent rhetoric stealest away the purposes of wrath; and to the guilty man, for one night givest back the hopes of his youth, and hands washed pure from blood; and to the proud man, a brief oblivion for</i>

</p>

<p>

<i>Wrongs unredress)

that summonest to the chancery of dreams, for the triumphs of suffering innocence, false witnesses; and confoundest perjury; and dost reverse the sentences of unrighteous judges... Thou only givest these gifts to man; and thou hast the keys of Paradise, oh, just, subtle, and mighty opium! 15

This strikingly beautiful passage from De Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium Eater reflects exactly the intoxicating power opium, its ability to reorganise the world and limit the pain felt by humans. It is followed, truly enough, by a quick descent into the torments of opium, the dreams which, at their most/terrifying, end in claustrophobia, a sensation of being walled in which we can find in the tales of Edgar Allan Poe. 16

This is the price which must be paid, not for escape into unawareness but for a different consciousness, freed from the limitations of human meanness, a multiple awareness of time and place, a place of protective light and shadow. This is how Pessanha finds "the panacea for all ills", perfectly in tune with his environment in Macau. Those who attribute the extended period of poetic inactivity (or at least the absence of any signs of output) to his opium addiction are in some ways right because, just like the chrysalis, his creativity was fermenting inside an inner heart.

Let us turn to De Quincey once again:

The opium-eater loses none of his moral sensibilities, or aspirations: he wishes and longs, as earnestly as ever, to realize what he believes possible, and feels to be exacted by duty; but his intellectual apprehension of what is possible infinitely outruns his power, not of execution only, but even of power to attempt.

The opium smoke, the magnificent, sinister sensations, form another of the threads the poet winds around himself to attain a new ordering of the world, to increase the distance -- another of the threads creating the protective casing housing the metamorphosis in which his profound disbelief prevents him from believing. He is left only the final step, the voyage in the ship which never reaches "anywhere, ever...".

THE HOUSE-FOR-DEATH

Let us return to Macau, to the house where Camilo Pessanha lived with his Chinese maid and lover... without ever officially recognising the children borne of the relationship! What kind of house was it? A house strangely detached from all Western references, a house for exile, the final refuge of a deeply embittered man whose only pleasure was Chinese art and an addiction to opium.

It is not difficult to recognise it. His final address was, for Pessanha, his own tomb, a space for dying, the home of the living corpse who dragged himself through the streets of Macau. Surrounded by barbaric wealth, Camilo lived in his home like a pharaoh in his eternal tomb. The collection itself was no more than an inextricable labyrinth, an antechamber off his own bedroom, his death bed.

There is an obvious, obsessive image in his poetry of ossification, mineralisation, a final solution for torment and pain. Living clippings of sand, Take my body and open up its veins... Turn my blood,... Saline crystals, See the living plasma in the sand... Similarly, in another poem: For the best, in the end, Is neither to hear nor to see... For them to pass over me and to feel no pain!... And I on terra firma, compact, trodden, Terribly quiet. Laughing because nothing pains me. Death, the slow prospect of mineralisation, foreseen as the only solution, the final panacea for a pain which not even opium or poetry could relieve.

Despite appearances, this is an organised tomb: two antechambers, increasingly difficult to gain entry, and the bedroom also filled with chinoiserie. The first room, for visitors, was possibly the only relic of sociability or, alternatively, the bare social minimum for gossiping outsiders.

Had it not been for the large, glistening European metal bed and a few books shoved in a wardrobe and on the chairs, we could have been in the home of any local Chinese. 17 This is an interesting point for it confirms what has been said above with all the accompanying symbolism. An old rosary hung from the headboard which, tears in his eyes, the poet told me had belonged to his late mother and which he always had by him. 18

It is good to see: once the two antechambers have been crossed, within the innermost part of his refuge, the poet lying curled up in a foetal position preserves a possession of his mother which brings him to tears every time he speaks of it. All houses have other houses constructed within them leading to a truly private space. For Camilo Pessanha, the return to his mother was his encounter with death, his last chance of purification. In death's arms, in the arms of his mother, the material being wasted slowly away, changing to mineral in an absurd mimesis of the house shell surrounding him. Finally, distance is created with regard to life itself and its accompanying pain. It is the image of his mother which he carries to his final resting place and which he cannot exorcise. Thus it casts a shadow as an archetype of disgrace and fatality.

Mother, death, regeneration. In his exile in Macau, in the cocoon of his home, in that room redolent of opium dreams, in that "east of the east of the Orient", Camilo Pessanha gave voice to his deathly dialogue in the final, lethal Orient, a larval spot for rebirth, obsessive, renewing death, the single avatar of purification.

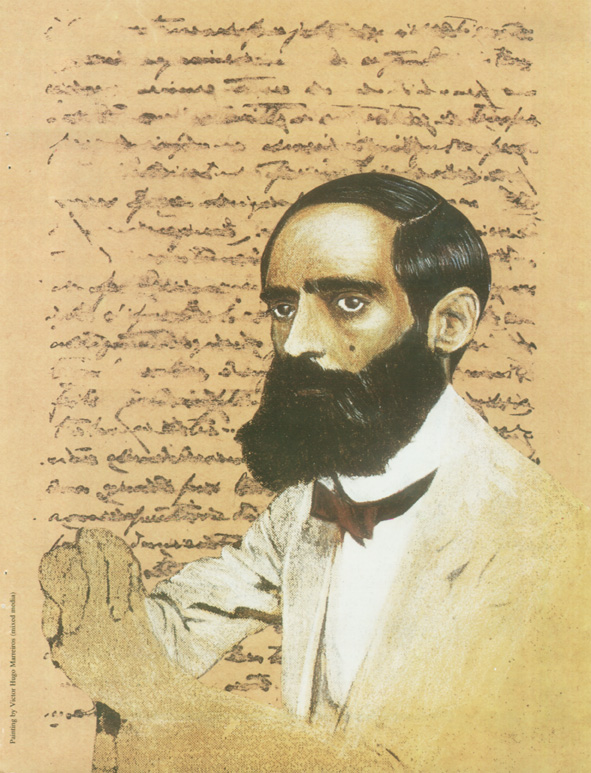

Painting by victor Hugo Marreiros (mixed media)

NOTES

1Bachelard, Gaston: La Poétique de l'espace. Presses Universitaires de France, 1957, p. 23.

2Amaro, Carlos:"Camilo Pessanha"in Pires, Daniel, Homenagem a Camilo Pessanha, ICM, 1990 (originally published in Ilustração, nº 6,16th March, 1926).

3Bachelard, Gaston: op. cit., p.46.

4"The rooms of houses are equivalent to vital organs... and the child spontaneously recognises the windows as eyes and feels the cellar and the passageways as innards..." Durand, Gilbert: As Estruturas Antropológicas do Imaginário, Presença, Lisbon, 1989, p. 168.

5There is opportunity for a complementary study on the other roles of the house, namely its place in the diachronism and persistent changes which it undergoes over the years.

6Cf. Heidegger, Martin: El Ser y el Tiempo, F. C. E., Madrid, 1984.

7Costa, Sebastião: "Camilo Pessanha"in Seara Nova, nº 85,29th April, 1926, quoted in Pires, Daniel: op. cit., p. 10.

8Costa, Sebastião, ibid., p. 9.

9Castro, Alberto Osório de: "Camilo Pessanha em Macau", Atlântico, 1942, quoted in Pires, Daniel: ibid., p. 50.

10Rego, José de Carvalho e: in Notícias de Macau, 11th February, 1968, quoted in Pires, Daniel: ibid., p. 30.

11Ibid., p. 26.

12Costa, Sebastião: ibid., p. 13.

13Quadros, António: "Introduçã à vida e obra de Camilo Pessanha" in Clepsidra e poemas diversos, Publicações Europa-América, p. 38.

14Schopenhauer, Arthur: Studies on Pessimism, Riverside Press, Edinburgh, 1937, p. 17.

15De Quincey, Thomas: Confessions of an English Opium Eater, Harmondsworth, 1971, pp. 82-83.

16For example "The Cask of Amontillado", "The Pit and the Pendulum" and "The Black Cat".

17Costa, Sebastião: ibid., p. 10.

18Costa, Sebastião: ibid..

*A distinction should be drawn between the original home and the secondary home, in other words, the space where the child discovers the world and peoples it with familiar places, objects and mysteries, and another, secondary place which man builds and inhabits which may or may not have the same spatial structure and emotional charge as the original home. This step brings into play a series of cultural rules. Camilo Pessanha's home in Macau belonged, obviously, to the second category.