In the Library of Kyoto University for Foreign Studies there is a rare book entitled Le Japon de nos Jours by Georges Bousquet, a French jurist who lived in Japan from 1872 to 1876. Both Edmond de Goncourt and Aluísio Azevedo consulted this book. It is indeed very rare and only specialized libraries in France have it. Its author is not even mentioned in any bibliographical dictionary of the XIXth or XXth centuries. Even the most comprehensive works do not make any bibliographical reference, although they mention his presence in Japan as a jurist. According to his own account, Bousquet was called upon to become the legal advisor to the Japanese government in early 1872. His book reflects a distant and objective observer. Luiz Dantas, a Brazilian researcher makes the following comment: 'In 1870, Le Japon de nos Jours was like a summary and update of information on Japan, thanks to its volume and variety of subjects dealt with, covering a basic knowledge of Japanese geography and history, as well as political and artistic considerations. The book refers to numerous French, British and German authors and contemporary publications like English newspapers published in Edo (today's Tokyo) or Yokohama. Therefore, it is really a reference book as it covers a wide range of subjects, updated information and enriched by the author's own experience as a traveller. The interest in Georges Bousquet's Le Japon de nos Jours is based on the use that Aluísio Azevedo made of it as a source of information which led him to follow Bousquet's book structure when writing his own book. In fact, the five chapters into which the manuscript of O Japão is divided, follows the same contents as the introduction of George Bouquet's work. O Japão is a contemplation of the country's history, from its mythical origins to the civil war before the Meiji Restoration in 1863.'(1)

Prior to arriving in Macau, Bousquet made extensive comments on the Japanese civilization. He noted the Kwannon-Sama cult and the Phallic cult which was quite widespread in Japan, mainly around Nikko. He admired Nikko's winter beauty: 'Those who have seen Nikko only in summer do not have the slightest idea of its winter charm, with its ice and snow under the sun.'(2) Bousquet was of the opinion that during the isolation imposed by Tokugawa, Japan was happy: 'Their civilization is not so developed or advanced as ours but it is complete and logical. They are happy. Our contact, our customs, our industrial machines make them curious and willing to learn. Will they be happier after losing their ignorance? Only the future can give an answer to this question.' (3) This comment shows signs of a longing for the past, for the ancient Japan, and this feeling was shared by other people like Lafcadio Hearn, Wenceslau de Morais and Edmond de Goncourt.

Kyoto seemed very melancholic to Bousquet, as opposed to Osaka's vitality. He made a plaintive comment that: 'Kyoto, the old capital of mikados, the nest of the Empire from where science, manners and arts imported from China spread in ancient times.' (4) In a more mundane remark he referred to the Japanese prodigality as a result of Buddhism: 'Around us, everything fades away, life is an illusion. What is durable on earth is the centuries old question asked by Buddhism.' (5) He pointed out the Japanese humour similar to that of Aristophanes: 'They have a high sense of humour, the ability to take advantage of frivolousness and stress the grotesque side of the human being.' (6) But he also referred to the great ability of the Japanese to pretend and lie. As to Christianity, Bousquet makes a remark which was to be repeated later by Morais and Hearn: 'Japan did not know intolerance, it was taught to them, a sinister lesson which would turn against those who had taught it.'(7)

From Japan, Bousquet reached China and the stillness of this country impressed him. To him, Canton was: 'A huge cesspool which comprised, within its walls, a very dense, ugly and gross population.' (8)

Bousquet then left for Macau aboard the Spark. The trip took ten hours and the route was full of pirates so that passengers travelled armed. Bousquet recalled that Macau was the oldest European settlement in China as it was founded in 1556. It was granted by Emperor Chi-tsang in exchange for the services rendered against the pirates. In 1877, the colony had thirty five thousand inhabitants, five thousand of whom were of Portuguese blood. He recalled the bygone power of Macau and its decadence after the establishment of Hong Kong: 'Even before arriving in Macau, we hear that this powerful city whose influence used to spread as far as China and Japan, is no longer as powerful as before. The Portuguese settlement was to experience all sorts of calamities: the first was the 1842 treaty which granted Hong Kong to the British, who soon transformed it into a Free Port. This diverted traffic to Hong Kong, as in Macau ships faced a poor harbour and demanding customs. In 1846 the Queen of Portugal abolished customs duties, but to no avail, since the Free Port role had been taken up by others; also, several campaigns on the part of the press and British diplomacy stopped the traffic of coolies which was indeed the city's wealth: finally, a fierce typhoon, followed by a huge fire destroyed the whole city from which it is still trying to recover.' (9)

Bousquet described Macau, with its picturesque hills 'planted in the middle of the sea, like a lighthouse at the end of a long dike.'

He stressed the Western features of Macau: 'As soon as you land in Macau you feel like you have travelled four thousand miles and suddenly you go from China to Europe. The upper part of the city looks like a provincial town of the South of France, with its empty and disorganized streets, clustered houses, churches and convents. In fact, we face true Catholicism with its See, four churches and many chapels. None of them is really a monument. The Praia area reaches the sea on its eastern side; here we can find the most beautiful houses, most of them destroyed by the typhoon of 1874 and now being rebuilt.' With its many fortresses, Macau was almost impregnable. Its officers spoke French fluently. Bousquet was biased towards the French and stated that: 'In these distant places, we tend to regard these people as compatriots, since they are also Latin people and are excluded by the British.'(10)

Bousquet referred also to the people of Macau: 'The population of Macau is an interesting blend. The Portuguese born in Europe are few- in general they are civil and military officers as well as some traders; there are also the Macanese, those people born in China of Portuguese parents and the Mestizos, a blend of Portuguese and Chinese blood, amounting to between four and five thousand. Finally, the Chinese who have learned different manners due to their contacts with foreigners, engage in trading and other similar activities. There are also dangerous bandits, despite the reinforcements received by the police. It is impossible to rout out the pirates who seek shelter in the city. As for the Mestizos, they either look very much like the Chinese or the Portuguese and live away from the European society; they engage in all sorts of business and keep a close grip on their women'. All social classes used to meet in gambling rooms. Foreigners would sometimes join in: 'Some Europeans from Hong Kong come to Macau, just to try their luck. '(11)

One Sunday, Bousquet attended the Feast of St. Joseph. The altar was decorated with flowers and lights, and Governor D. José Maria Lobo d'Ávila presided. The garrison presented arms and the crowd bowed to the priests' speeches. Attending this universal cult, celebrated with splendour, made Bousquet feel as though he were back home.

Like all foreigners, Bousquet paid a visit to the Macau Grotto and accepted that Camões had resided in Macau: 'In 1550, after being expelled from Portugal and arrested in Goa due to some court intrigues, the poet sought shelter here. In the middle of a garden, on a rocky mass from where one can see the great extent of the sea there is a grotto; rumour has it that it was in this grotto that the poet wrote The Lusiads. If its current owner had not painted the grotto walls white and erected a bust with some poetic transcriptions, this tradition could very well arouse some kind of melancholic appeal. It would be a hard task to give an account of the graffiti written on the walls in all languages. It is therefore sad to witness how anonymous people dare write their names near the name of a great man.' (12)

Street in front of St. Domingos' Church (1836) by G. Chinnery (Paint and sepia on paper, 19.5 x 28 cm; Luís de Camões Museum Collection).

Street in front of St. Domingos' Church (1836) by G. Chinnery (Paint and sepia on paper, 19.5 x 28 cm; Luís de Camões Museum Collection).

Next, Bousquet referred to the effects of the typhoon and the barracks from where Chinese workers left for Peru: 'It is now known that the Portuguese government gave up this kind of trade, thanks to the influence of England. In fact, the abuses performed during the trade of these miserable people, who often fell victim to deceit, should be put to an end. Since this industry has just moved to Hong Kong, it would have been much better to have kept it in Macau.'(13)

At that time, the public garden near Praia Grande used to attract strollers. However, as it was the rainy season the Portuguese ladies, the beauty of whom Bousquet praised, did not wish to spoil their fashionable Parisian clothes. The Frenchman also admired France's elegance, pleasures and attractions: 'Macau used to be a city of pleasure, but the wheel of fortune changed all that. The elegant life had to wait for better days. In this colony, one can feel the pleasure of sound social contacts (...) Foreigners are welcome, people speak of their memories back home. Despite its misfortune, France still enjoys moral prestige and has much intellectual influence. Our literature, arts, theatre and mainly Paris, the magical Paris which is known all over the world, is the topic of conversation among our Latin neighbours. ' French literature was known in Macau: 'It is easy to prove that there is no intellectual culture without reading French writers like Victor Hugo and Musset, the verses of whom keep the same splendour when recited by a Portuguese lady. The habit of giving the host the opportunity to address his guests at the end of the meal is enchanting indeed. The first toast goes to France. This toast is made with real fervour. The night ends at the governor's house, drinking tea.' (14)

Bousquet ended his story of Macau by praising the glory of Macau and the Portuguese colonization: 'The impression that I have of Macau is that of a powerful energy fighting against fate, trying to win back a place which used to be the glory of its colonial empire; upon departure, one wishes that the Portuguese government's efforts will be successful. The Portuguese and British deal with the Chinese differently. The former prefer persuasion rather than force. Even though I do not wish to judge the merits of either approach, and taking into account that the Portuguese have been in Macau for two centuries and the British only thirty years in Hong Kong, I would say that I prefer the results achieved in Macau. The inhabitants of Macau seem more docile and less constrained than those of Hong Kong. '(15)

Camões Grotto (Photogravure by P. Marinho taken from a photo taken in 1873 (?) by Hong Kong's Chin Atay. Supplied by Macau's Dr. Lourenço Pereira Marques, in 'Ta-Ssi-Yang-Kuo',

FINAL NOTES

Georges Bousquet explained the nature of his mission: 'Called upon in early 1872 to take up the post of legal advisor to the Japanese government, I came to stay for four years in Japan and I never missed the opportunity of learning about the lives of the people unknown to me. Their civilization is much older, as refined and less mature than ours. Impressed with the difference between its places and those of our Western culture, I was led to look into the structure of the nation, its aesthetic and moral manifestations.' (Avant-Propos, I p.3).

Bousquet also wrote a few pages about the history of the Portuguese in Japan: 'Mendez Pinto, a Portuguese adventurer, is said to be the first European to have reached Japan (1542). The friendly reception given to him by some 'daimyos' who were eager to learn how to use fire-arms made his countrymen return to Japan, soon bringing the Jesuit priests who were already in Macau. The major Portuguese settlement was Hirado on the west coast of Kyushu.' (p.32)

Bousquet praised the riches and harmony of the Tokugawa regime: 'And if people's happiness is based on stillness there has never been a golden age like this one, anywhere on earth.'

Bousquet always admired the beauty of Japan, hating the Western clothes used by the Japanese. He also wrote of his experiences with the habit of 'lying': 'People lie for fun, negligence, disdain, boredom, shyness, amusement. They lie so much and so well that they do it as a habit.' As regards the customs, he noted the lack of courtship: 'There is no courtship here: our expressions of love make them shrug their shoulders.' (p.96) He also described the use of the seppuku (ritual suicide).

He referred to Kamakura, Hakone, Edo and Osaka. He wrote a description of Kyoto: 'Kyoto is a large wooden Versailles, symmetrical, sad, dying, abandoned by life which has taken refuge at Yedo. Everywhere there are signs of pleasure, as opposed to the lack of signs of work: luxurious shopping, silk, gewgaws, tea houses, guitar concerts, the grandeur of a withered, decadent Babylon.' Bousquet's enthusiasm was aroused by Nikko: 'This is a huge and empty mountain, where a large avenue, bordered with centuries old trees, climbs the snowy basalt summits. The sound of rivers and waterfalls is everywhere. Government officials rest there and it is there that the most powerful man in Japan wants to rest when he becomes a god (...) Nikko's mausoleums are more important than any other temple in Japan, due to their magnificence and preservation: even in Kyoto, despite the wealth of this sacred city, nothing can compare with them. But what makes Nikko superior, is the impression of mightiness provided by the surroundings. At the bottom of the Gangen-sama temple the human soul feels lifted and crushed. We are surprised with the stones, the colossal roofs and the wonderful trees, which seem to be in eternal mourning. '(p.216)

Ladies wearing the dó followed by servants with parasols in Macau, by G. Chinnery (ink and paper 17.8 x 21.1 cm, Luís de Camões Museum Collection).

A review on Azevedo's O Japão was released in 1985: 'At the time the West was very interested in those islands which now form the Japanese nation. Europeans were very keen on Japan. Aluísio Azevedo became sensible to the country's traditions and efforts to preserve its identity. Like many other historians and chroniclers on Japan, our novelist marvelled about the legendary persons who helped in the formation of those people and to him the opening of the commercial transactions with the West, which was only possible thanks to the arrogance of Commodore Perry, who was working for the Americans, was a means of corrupting the local principles and finish ing the peace achieved after centuries of wars.

The discovery of Japanese art was a tremendous inspiration to the European Impressionist Movement. Eager for Eastern exoticism, the Western civilization was attracted to everything related to Japan.

In his O Japão Aluísio Azevedo writes five chapters about 'an impenetrable world of traditions accumulated throughout twenty two centuries of isolation'. He gives us an account of the people's history from the mythical stages to the inception of the Shogun regime, and its extinction in 1867. He refers to the rare contacts between Western people and Japan, Marco Polo's sources, the exciting report of Fernão Mendes Pinto, the Jesuits' work, especially that of St. Francis Xavier, the Portuguese and Dutch presence, and the tragedy of the Christians (...) The book is well designed and there are some notes by Luís Dantas entitled 'Chaves para Compreender O Japão de Aluísio Azevedo (Key to Aluísio Azevedo's O Japão).' These notes correct and complement the novelist's work, in "0 Japão de Aluísio Azevedo," Suplemento Literário de Minas Gerais Aluísio Azevedo's O Japão, Minas Gerais' Literary Supplement) by Fábio Lucas, no. 971, dated 11th May 1985, p.10.

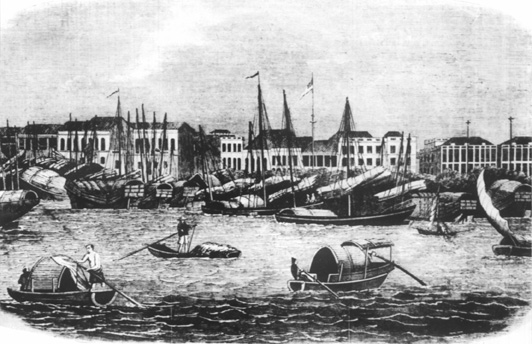

Foreign settlements in Canton. (In 'Illustrated London News of 18th July, 1857. Published in Hong Kong Illustrated - Views and News, 1840-1890).

NOTES

(1) Luiz Dantas: "Apresentação: in Aluísio Azevedo O Japão, (São Paulo, Roswitha Kempf/Editores, 1984), pp.7-41).

(2)Georges Bousquet: Le Japon de nos Jours et les Échelles de L'Extrême Orient Ouvrage contenant toris cartes (Paris, Librairie Hachette etc Ce., 1877), I, p.219.

(3)Idem, p.227.

(4)Idem, p.228.

(5)Idem, p.245.

(6)Idem, p.394.

(7)Idem, II, p. 115.

(8)Idem, p.332.

(9)Idem, p.334.

(10)Idem, p.336.

(11)Idem, p.337.

(12)Idem, p.338.

(13)Idem, p.339.

(14)Idem, p.340.

(15)Idem, p.341.

start p. 76

end p.