Throughout history, Portugal has always placed herself at the forefront of political and social ideas. Portugal has always been able to learn from her mistakes, make up for what is lacking and to forge ahead, jumping from the tail to the head of the vanguard in intermittent steps. These steps maybe explain why such a small nation has retained its independence over eight hundred years, reaching out to an empire covering half the world.

Portugal led the civilized world in abolishing the death penalty and was also one of the leaders in bringing an end to slavery.

Nevertheless, it is in this area that the Portuguese still carry the bulk of the blame for the trade in slaves across the Atlantic to the Americas.

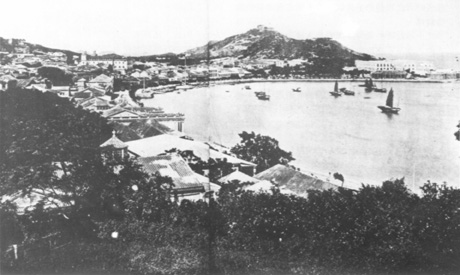

The Praia Grande, seen from the southern tip, c. 1870. To the right, in front of S. Francisco, the scaffolding of the Military Club in the early stages of construction (China, the Land and its People, Early Photographs by John Thompson, revised and edited by John Warner, 1979).

The Praia Grande, seen from the southern tip, c. 1870. To the right, in front of S. Francisco, the scaffolding of the Military Club in the early stages of construction (China, the Land and its People, Early Photographs by John Thompson, revised and edited by John Warner, 1979).

Portugal was a very late starter as far as liberalism was concerned, but once her revolution was over, the nation was presented with the most progressive constitution to be found in a Europe which was in itself very liberal.

The world, however, remembers more of the 1823 Vila Francada counter revolution to abolish to constitutional régime in Brazil, than the September Revolution which re-established the Constitution. History has preserved the image of D. Miguel, an illiterate bull-fighter, as the outstanding figure of the first quarter of the eighteenth century, rather than the liberal D. Pedro, an enlightened mason. Setting aside the controversial aspects of this still recent period, the manner in which Portugal withdrew from Brazil, with no conditions and no reserves, left the image of having condemned a defenceless nation to the higher forces of destiny rather than protecting it.

The Portuguese process of error and review has meant that there have been blemishes which in the opinion of other countries, motivated largely by political interests, continue uncorrected, although facts would indicate quite the opposite.

Once the glorious fifteenth century had come to a close, Macau sank into oblivion only to return to the minds of the international community three centuries later, when there was no longer enough Japanese silver to show off the wealth which came from the little balls of opium, destroying the energy of an entire empire. The XIXth century revived Macau, marking the territory as a centre for vice and an example of disregard for international norms.

While the opium trade had earned Macau international condemnation, the issue of the coolie trade attracted a level of attention which surpassed regional limits and reached the newspapers, chancelleries, parliaments and streets of an educated Europe which had just put an end to trafficking in slaves. This was the first time that humanitarian interests had taken precedence over financial ones on such a great scale.

The coolie trade began to gather steam from the end of the first half of the XIXth century. This was the point at which the abolition of slavery had begun to bite and there was a severe shortage of manpower in the huge sugar cane, cotton and other plantations.

Many South American countries then began to take in young Chinese fleeing from the misery of rice-paddies devastated by floods and the overwhelming lack of opportunities afforded by a country in the midst of violent political and social upheavals.

The opening of the Chinese ports, following the second Opium War, meant that there was not only a door into the country for Western industry, but also a door out for those who yearned to leave the most heavily populated country in the world and search for subsistence on other shores.

While Central and South America required manpower for the plantations, North America was crying out for men to work on the railways, the new mining industries and even the huge cotton farms being set up in California. Australia was in the same situation but on a smaller scale.

Not enough people were choosing to leave China, however, to satisfy these needs, and it was here that the emigration agent came into existence, completely disregarding all values in human relationships.

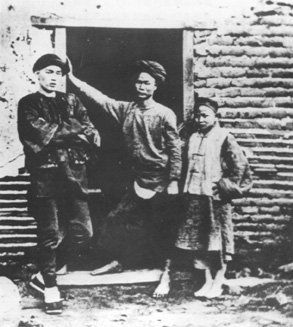

Group of Chinese men in Amoy, southeast Fuquien Province (idem, ib, ob cit.)

Group of Chinese men in Amoy, southeast Fuquien Province (idem, ib, ob cit.)

In accordance with Eastern mentality, which seeks an intermediary in even the most unusual situations, the trade of emigration agent for the Americas grew and flourished, giving rise to an anomalous situation in which the article being traded was a human being, just as the case had been not so long beforehand with slavery.

Western powers were still very sensitive and anxious to rid themselves of any sense of blame connected to their history of slavery. Given the victory of the Northern troops in the American Civil War, they felt they were in a position to react to a situation with which they were unhappy.

This reaction, led by England, was not entirely free from political and economic motives, namely competition from other powers against the British Empire. Nevertheless, it is true that the moral issues regarding the trade in coolies rated more highly than the underlying material considerations of the government in London.

Traditionally, the Chinese emperors discouraged emigration and they went so far as to consider it an act of betrayal which could be punishable by death. Consequently, the heavy apparatus of Imperial China was mounted in opposition to the American 'El Dorado', and a prohibition against leaving China was rapidly put in motion. The only remaining door out was through Macau's Inner Harbour. Just as Macau had previously been the only service port for taking opium into China, the coolies came to be processed only through Macau.

Statistics show a clear picture of the increased role of the Portuguese colony in a business in which Macau was once again nothing more than a middleman.

(idem ib ob cit: China The Land and its People)

(idem ib ob cit: China The Land and its People)

In 1856, two thousand, four hundred and ninety three emigrants left via Macau, the number reaching ten thousand, seven hundred and twelve ten years later. By 1873, there were over thirteen thousand emigrants but this was the year when the international community was to point an accusing finger at the Portuguese government of Macau.

Before the foreign nations could join together against the degrading trade by sending humiliating ultimata, Portugal decided to bring to an end a troublesome situation in which not even the profits were enough to make the shame worthwhile.

A campaign against trafficking in coolies was initiated without a moment's hesistation by Andrade Corvo, one of the few Portuguese politicians who dedicated his public life to the cause of the colonies. The move attracted the support of governors Ponte e Horta, Sérgio de Sousa and mainly the Viscount of S. Januário. The emigration of coolies had given rise to a variety of new professions in Macau, connected with the recruitment of Chinese youths for the foreign contractors who anchored in the Inner Harbour to wait for them.

Despite the sudden increase in trade, however, it was still not particularly profitable for Macau. As João Andade Corvo was to write: "For Macau, emigration has not brought economic development. Rather, it seems to have engulfed all activity in the colony, eradicating natural sources of wealth. Macau could and should be a vast emporium, a market open to world trade with China. Instead of holding this position, there is hardly any trading done in Macau other than that essential for its own needs and a limited amount of coastal trade. Imports arrive on large vessels and exports, mainly opium, leave on Chinese boats." Along the same train of thought, the Viscount of S. Januário, Governor of Macau and Timor stated in 1873: "The Portuguese nation suffers much from emigration and is not the party to reap the most gain from it. This movement in workers enriches, principally, the foreign countries (Hispania, Peru and so on). It is dominated by foreign capital and brings wealth to foreign companies and agents. All the same, it does serve to increase Macau's revenue and causes a certain amount of business and movement of funds within the territory, to the benefit of the population."

On a moral level, the position of the thousands of young coolies who waited in Macau for their turn to embark was little different from that inflicted on the African slaves, despite regulations published by the government.

The agents, usually in the service of other people who in turn worked for one of the eight foreign companies legally registered in Macau, would set off for the Chinese mainland in search of candidates for emigration. The need to meet preset demands and the financial losses which would accompany a failure to do so led the agents to use all kinds of tricks to entice young men, little more than adolescents, away from their families in the villages. The promises of untold wealth and the guarantees of a safe return were staple lines fed by the agents, who thus managed to fill the warehouses in Macau, where the candidates were deposited. Once in Macau, any dissenter regretting his decision would be locked up. Then, in return for a fixed sum of money, another coolie, using his name, would declare before a committee of the Portuguese government that he accepted the conditions of the contract and was emigrating under his own free will. The fate of the majority of these emigrants, more often than not under duress, was to arrive in Peru or Cuba where, as Eça de Queirós was to point out, the lack of labour was so acute that the mills were completely dependent on the influx of immigrants from Macau.

Although Macau had legislation intended to protect the rights of the coolies, the situation was in fact uncontrollable. The extent of the problem inside China was revealed by a Chinese deputation to the governor of Hong Kong in 1872, in which some of the tricks used by the agents to make the coolies leave their villages for lands of milk and honey, playing on their ignorance, were detailed. The report they submitted stated: "Sometimes, when these villagers have been tempted by fraudulent bait, they change their minds and when they arrive at their destination and realise their position they do not want to leave. They are immediately locked up in a separate house and punished severely with whips. Then they are taken to a shed where a supposedly official agent awaits them and interrogates them until they finally declare that they want to emigrate. If they say they do not want to go, they are immediately punished for having accepted money (during contracting) and refusing to fulfill their side of the contract. The coolie agent follows them everywhere and relates their story. The supposed official agent sentences them to a heavier punishment. Then they are taken somewhere else and the punishment is repeated. They are whipped again and again until they show they are willing to emigrate and only then does it stop. On the following day, they are taken to the true official agent to be examined.

These coolies from the countryside, terrorized by the treatment meted out to them, are forced to give their consent. Many of them have never even seen a foreigner before, let alone travelled outside their own country, even to Macau. When they are far from home they want to rebel but they have no method of doing so. Who can help them? Perhaps somebody might secretly tell them that they should flee, but then orders are given for them to be tied up and taken to another shed where they suffer the same treatment. They are whipped pitilessly until they can do nothing but accept their fate".

The abuses which were rampant outside Macau also proved to be impossible to control inside the city. A countless number of tricks allowed the agents to avoid observing laws and regulations and they were even able to avoid direct checks from the authorities. At the same time, the coolies were loaded like cattle onto ships anchored outside Macau waters, while the Portuguese government issued meticulous regulations relating to hygiene, space, water and light in transportation.

In spite of this, statistics revealed by the British parliament on mortality levels in the transportation of coolies are enlightening. From January, 1847, until December, 1857, of the twenty three thousand, nine hundred and twenty eight coolies who left China, three thousand, three hundred and forty two died, in other words a mortality rate of 14%. The Portuguese Consul in Peru wrote a letter to the governor of Macau at around the same time, stating that up to half the passengers and sometimes even more than that died, being the victims of scurvy and other diseases.

A poignant example of the tragedy being lived out occurred in the mid-1870's with the case of the ship Dolores Ugarte from San Salvador. The Dolores Ugarte set off from Macau with a load of six hundred coolies, destined for the port of Callao in Central America. The ship could only hold eight hundred tons and was carrying an excessive number of passengers. These demonstrated their desire to mutiny right at the beginning and so they were confined to a narrow space below deck. For the first three weeks the coolies were transported like prisoners, but then they were allowed to go above deck in groups of fifty for an hour of exercise each day under the watchful guard of armed crew members. In spite of these precautions, there were disturbances, and in one of these eighteen coolies were simply thrown overboard. To make the situation even worse, food and water were running short and the coolies were given miserable rations. They were forced to use what little money they had to buy mugs of water from the greedy crew. Disease spread like wildfire through the tragic human cargo and the boat had to stop in Hawaii to deposit huge numbers of bodies. The Hawaiian newspapers denounced what had happened and the horrific descriptions of the unhappy fate of the blinded, maimed and deceased victims of starvation, typhoid, scurvy and dysentry reached across the world.

Later, the Dolores Ugarte anchored in Callao and the Portuguese Consul of Peru sent the following report to the governor of Macau: "The Salvadorean frigate "Dolores Ugarte" anchored in the port of Callao after a voyage from Macau carrying on board four hundred and eighty-six of the six hundred and five Chinese settlers taken on in the port of origin. Forty-three had to disembark in Honolulu due to illness where they have been detained, and seventy-six died on the voyage from natural causes. From information collected by this consulate, it seems that the passengers were well treated throughout their journey."

At around the same time, Eça de Queirós, the writer, had been appointed Portuguese Consul to Habana, his first diplomatic mission. He was to write the following account of the treatment of arrivals in Cuba: "Eighteen months ago, a Chinese man arrived on the island (Cuba) not as a settler, but as a free subject of Macau. A doctor by profession, he had come employed in this capacity on a boat of emigrants. The unfortunate man was arrested by the police as soon as he stepped ashore as a settler with no papers. He has been held in the garrison for eighteen months and recently managed to come to the consulate and demand his rights as a Portuguese citizen. He has been overworked and is terrified. One month ago, I made an offical complaint requesting for him to be freed immediately, but so far there has been absolutely no response and the poor man continues in the garrison ".

Eça de Queirós, who "always adopted the approach of a disinterested spectator observing with irony and a superficial smile", was not able to remain aloof from the dramatic situation confronting him daily and which he had insufficient powers to ameliorate. He wrote vigorous directives to the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Portugal, describing the situation and demanding measures to remedy it.

The diplomat-writer exposed the precedures employed by those who owned the settlers and the tacit consent of the authorities, reminding them that the Cuban owners "on the eve of losing their slaves, are attempting to wreak their revenge by replacing indigenous slaves with imported slave settlers".

He recognised by the early 1870's that the Asian labourers were living in inhumane conditions: "Over eighty thousand defenceless settlers with no rights, were left to be exploited by their owners because of tyrannical legislation, the whims of the authorities and the requirements of the councils. The Portuguese consulate can do nothing to modify this injustice despite its zealous desire to do so... ".

On his first diplomatic mission, Eça was to describe the "new slavery" of the "New World" in the following terms:

"As you know, this legislation is dominated by two major factors: 1. The settlers who arrived on this island prior to 1861 are freemen and entitled to a foreigner's identity card and to use this to contract freely for a price to which they agree and so on. 2. The settlers who arrived here after 1861 and who have completed their first contract must leave the island within a space of two months or make a second contract for another six years.

This is the law: let us now examine how arbitrary it is when put into practise. An old regulation states that every settler who has completed his first contract shall be handed over by his owner to the local authorities who shall then lock him up in the "store". The "store" is one of the most characteristic institutions of this legislation. Each provincial capital has its own "store", consisting of long sheds or huts where the settlers who have completed their first contract are shut up as if they were in prison, awaiting a new contract. The store has two purposes. Firstly, it prevents wastage of labour in the intervening period between contracts. Secondly, it prevents the settler from making a free contract, leaving the island covertly, escaping into the interior or freeing himself from the control of the plantation owners and working on council contracts in return for nothing and under a guard as watchful as it would need to be for felons. The "stores" are for the most part lacking in hygiene, decency, order and humanity. The supply of food for the settlers is tendered out to tavern owners who then profit while the settler suffers hunger. And these miserable souls are kept in these conditions until an owner goes to the "store" to reclaim a certain number of hands to tie to a second contract. Thus the "store" is an abject interval between two slaveries."

This was the situation as Eça de Queirós described it, but in fact the coolies were protected under law by the Portuguese government and held documents to prove this. However, legislation and reality were two quite separate issues as the writer pointed out:

"The stores hold a large proportion of the settlers who arrived here before 1861 and who are thus entitled to a Portuguese identity card. Becausethey are under a prison régime, however, they may not reclaim their card and thus they lose all its legal benefits. So we can see that the law frees them and the regulations enslave them. It is also the case that a large part of those who arrived before 1861 are now working on a second contract in the interior and, as they cannot come to Habana to prove claim to their rights, for there are few planters who would let them lose two or three days work to come to the city, they also fail to benefit from the regulation which favours them. So, with one part of these settlers in the store and another part on the plantations, only a small number have access to their card and the guarantees of free labour."

Having outlined the realities of the situation, Eça went on to present his minister with a strong argument urging him to come to the rescue of the thousands of workers who were dying in Cuba: "The shortage of manpower on the island is acute. Many factories have stopped production. As the slaves are freed, the need for settlers will grow. The importers do not want to go to Hong Kong or Canton for them as the English government will only allow them to be contracted for five years and so they are forced to go to Macau. The day when Macau closes its doors to emigration, the bells will toll for the sugar industry in Cuba. Cuba's dependance on Macau is the reason why any demands that the government of His Majesty makes will be accepted.

I beg you to deal with the matters I have brought to your attention as you will. Reforms will mean that the government of His Majesty can bring justice to the one hundred thousand settlers and offer a dignified response to former accusations. I am sure Spain will also see the justice in this reform and the nation which if freeing its own slaves cannot logically enslave its settlers."

The defence of the settlers unleashed by Eça de Queirós in distant Cuba had major repercussions in Lisbon and the minister responsible, Andrade Corvo, set himself to taking radical measures. He had been convinced that the existing legislation was ineffective in view of the complete failure of the regulations to protect anybody or even to save Portugal's face in the international community.

His intention was to put an end to the emigration of coolies from Macau and thus eradicate a disgrace which had been going on for more than a decade.

Moreover, everybody was united on the need to close this chapter of history. The position of the Leal Senado is a prime example of this stance given that here was a body which tended to comply or to negotiate terms before taking up a position on any issue.

The senate's attitude towards the coolie trade is expressed in a council report in response to a petition signed by a large number of Portuguese and Chinese who were protesting against the monopolisation of the way in which coolies were contracted in Macau.

The petitioners defended the legitimacy of their business and also the free competition with the resulting fluctuations in price produced by this.

The Leal Senado, however, leaving the legal questions aside for them to be dealt with by the relevant authorities, took up a clear position in defence of the "good name, honour and morals of the council" in its role as "promoter of the true wellbeing of the population ".

The report was quite emphatic as to the fact that Macau was becoming impoverished by emigration and it stated: "Emigration, as a result of the disgraceful abuses which have been made, has brought upon Macau a terrible reputation, the hatred of the Chinese, the disdain of the Europeans and enmity from the neighbouring districts of the city."

The report went on to state that: "It is immoral to consider emigration as a trade as this turns men into merchandise. It is equally immoral to put a price on an emigrant's head, the reason for this being obvious. It is even more immoral to have high and low prices as competition, or any increase in traffic, has negative effects here as well as in Peru and Cuba. Here it increases the incentives for committing crimes and so is immoral. There it increases the work of the settler and so is barbaric and unjust. The blame for such a deplorable situation lies, contrary to the opinion and advice of respectable people, in having allowed the emigration trade to clasp so many of the inhabitants of this city to its breast, and that the prosperity of the city should have been handed over to such an economic absurdity".

The report ended on a resounding note: "In the opinion of this senate, in protestation against the desired intentions of the petitioners who want to turn emigration into a business and thus into slavery, the only useful step which can be taken to safeguard the emigration which is taking place here is to ensure that it really is emigration as Your Excellency would wish it to be and in accordance with the desires of the Portuguese Government. It must thus be put on a firm foundation of liberty and free volition on the part of the emigrants with an equitable and fair contract and a guarantee that it will be respected. Any dealings with agents should be completely prohibited as this is exactly the hinge upon which this trade in men, slavery in fact, rests".

(idem ib ob cit: China The Land and its people)

By refusing to comply with the petition, the Leal Senado marked, without a shadow of a doubt,its whole-hearted condemnation of a business which directly and indirectly was contributing to the livelihood of an average of nine thousand people, a number which assumes its real proportions when we bear in mind that the total population of the territory by the 1870's was around twenty thousand.

Despite the fact that at least one hundred and thirty "Portuguese were involved in the traffic of coolies in the 1870's, the five contracting companies which existed in Macau were, according to Robertson, British Consul in Canton, either from South American countries or from the United States of America, while the ships which carried them were almost entirely from other countries.

In 1847, João de Andrade Corvo, Secretary of State for the Navy and Colonies, put an end to this national disgrace in the name of the "integrity and honour of the Nation". It had just been too similar to slavery which had been progressively abolished from 1858 onwards.

The Viscount of S. Januário put the lid on the business in accordance with orders received from Lisbon on the 27th of March, 1873. He anticipated a "certain crisis" but recognised that what was taking place was "a great reform, dictated by morals, by a desire to maintain international relations and by the dignity of the nation which, while the fault was not ours, it is true that by allowing this system of emigration to be carried out through our port with the sanction of the Portuguese Government on the contracts made here, meant that we were highly responsible".

When the coolie trade ended, Macau was no longer of interest to the rest of the world. The city gradually became less and less in contact with the outside world other than Hong Kong and ultimately it was Hong Kong that prospered.

Translated by Marie Imelda MacLeod

This photograph and the ones beforehand were taken between 1868 and 1872 by John Thompson as part of a photo report which showed the West the first images of inner China. Street urchins and opium addicts were the special domain of the coolie agents (idem ib).

* Reporter and researcher on Macau's history.

start p. 39

end p.