THE FIRST CONTACTS

Information about China was passed to us for the first time by Marco Polo and although it was not very clear it was a novelty. However, only a few centuries later, through the Portuguese who were accustomed to discovering new places, we came to have more knowledge of the Celestial Empire.

As discoveries were progressing, new posts were established to support new ventures. Malacca was an example of such a post which served as a back-up to reach China. The Portuguese took control of Malacca in 1511 and this was of major importance in the first contacts with the Middle Empire, because it was there that the Portuguese started to think of reaching China.

After the discovery of the maritime route to India, King Manuel I learned of a people - the Chinese - whose features were different from those of any other known people. This information supported Marco Polo's reports and made the King very anxious. Then, on the 13th of February 1508, he sent Diogo Lopes de Sequeira with instructions to discover new land between S. Lourenzo Island and Malacca, as well as collect information on China, its people, trade and religion.

Meanwhile, Afonso de Albuquerque, who had just conquered Malacca, met there some Chinese who were very well treated. This great captain gave them all the necessary means to return to their homeland. It is yet to be known whether that move had any connection with King Manuel's wish to collect information on China.

Soon after the discovery of the maritime route to India and when they were still recovering from this major expedition, the Portuguese were already planning to reach China, a country whose wealth was as yet closed to the newly-born European capitalism.

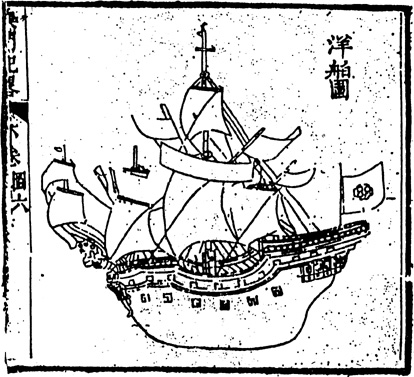

After all the preparations had been finalised, Jorge Álvares left for China from Malacca. Although this was not an economic or commercial expedition, nevertheless we know that the explorers had this in mind. The prime goal was to collect information on China's geographic location and its major trading ports. So it is believed that on this first expedition they reached Canton, the most important trading port in China.

Jorge Álvares reached Tamão, in the Pearl River Delta, in 1513 and there he erected a stone monument with the Portuguese Coat of Arms. It was extremely important to establish lasting contacts with China. Thus in 1516, Jorge de Albuquerque, Governor of Malacca, sent Rafael Perestrelo, an Italian working for Portugal, to try once again to enter China, but this time with commercial objectives. Rafael Perestrelo reached Canton and became very enthusiastic with what he saw. On his return, he convinced the Portuguese authorities that sending an embassy to China would be advantageous.

As Perestrelo's suggestions were accepted, an expedition left from Lisbon with the purpose of establishing diplomatic relations with China. The leader of this mission was Fernão Peres de Andrade who had the pompous title of 'Commander of the China Voyage'. Tomé Pires, pharmacist and naturalist, was sent as Ambassador.

In August 1517, after the last preparations had been made in Goa and Malacca, the fleet reached Taman Island. From there they left on the last stage of their voyage and finally arrived in Canton. Tomé Pires and his entourage were left there with letters and presents for the Chinese Emperor.

The commercial activity was successfully carried out by Fernão Peres. Keen to find out as much as possible, he sent one of his men to explore the Chinese coast up to Shant'ou, since he wanted information about Liu-Kiu Island (Taiwan) which was later called 'Formosa' by the Portuguese.

However, the diplomatic mission was disastrous because of the behaviour of Simão Peres de Andrade, Fernão Peres de Andrade's brother. When sent to Tamão to look for Tomé Peres, Simão Peres built a fortress and attacked some Chinese ships. Because of this, the Chinese authorities several times postponed any audience with the Ambassador and his entourage.

The case was worsened further because the Chinese did not accept the style in which the letter presented by Tomé Pires was written. They argued that it did not conform to the humble principles required by the Chinese Court (1).

Furthermore, the King of Bintan, a protégé of the Emperor of China, asked the Emperor not to give the Portuguese an audience because they had taken Malacca away from him. He warned the Emperor that he should be on his guard as the new arrivals wanted to collect extensive information on the country and then conquer part of it. Shocked with these reports, the Chinese sent Tomé Pires to prison where he finally died.

The hatred for anything that was foreign increased. An imperial decree ordered all foreigners to be expelled and prevented any trading with them from taking place. The Port of Canton was also closed to foreign ships.

But the Portuguese did not give up. They decided to go on with their objectives. They had travelled so far to expand their commerce, civilization and religion and they would not give up.

However, there were no signs of improvement. Martim Afonso de Melo was sent to try a peace, friendship and commerce treaty with China but he was received as an enemy and was forced to retreat with heavy losses.

This hostility lasted from 1522 to 1554. Yet in spite of this, the Portuguese continued to sail the Chinese seas and visit Chinese ports, during which time they carried out their trade. A substantial underground traffic operated with the complacent approval of the Chinese subaltern authorities. This can be explained by the fact that as in any feudal type of government, the central power was exercised by the provincial governors or mandarins who were in fact absolute rulers. It was then that the Portuguese set up some settlements on the Chinese coast, such as the Liampo and Shant'ou settlements.

Shant'ou grew quickly. But all commercial relations were brought to a halt since the mandarins feared that such a fast growth would show the central government their connivance with the Portuguese merchants. The war with the Portuguese broke out and only thirty out of five hundred Portuguese settlers in Shant'ou survived.

There were new trading prospects when Japan was discovered in 1542. At the time, traffic between China and Japan was mutually disallowed and the Portuguese took advantage of that. Besides, the Portuguese held exclusive rights for the circulation and trade of products.

Conditions improved and the Portuguese returned to Liampo and Shant'ou, which recorded a spectacular growth, thanks to trade with Japan.

However, in 1548 the Portuguese were once again expelled from those two settlements when the Chinese authorities felt that China was not making any profit. Showing again no signs of giving up, the Portuguese moved to the South from where they would be expelled too.

Everybody profited from the Portuguese legal or illegal trade. In the latter it was necessary to find an uncompromising solution. As regards the Chinese provincial authorites, they began to be more flexible because they were profiting from the illegal trade.

Around 1550, Sino-Portuguese trade experienced some improvements when the mandarins of Canton authorized the Portuguese to set up a settlement on Sanchuang Island in the Pearl River Delta. Later, the Portuguese left Sanchuang Island and settled on Lampacau Island, midway between Sanchuang and Macau.

As Sino-Portuguese relations were easing, the setting up of a settlement in Macau, a small piece of land in the Pearl River outfall, was drawing closer. Macau would then become the landmark of Portuguese presence in the Far East.

The Portuguese were allowed to settle in Macau by the Governor of Canton, upon a request presented by Captain Leonel de Sousa. With this, trading and sailing relations between Portugal and China were regularized.

The first contacts of the Portuguese with Macau, a small fishing village, date back to this period (1550-1557).

THE PORTUGUESE SETTLEMENT IN MACAU

When the Portuguese reached Macau, this territory was insignificant to the Chinese. China was busy governing its huge country and attached no importance whatsoever to the tiny coastal peninsula.

Trading activities in Macau were insignificant compared with those between Chinese provinces. Besides, sea trade did not constitute part of the Chinese economic activities because it called for contacts with foreigners. This can explain why, at the time, inland cities were prosperous while coastal villages were dependant upon the wishes of local mandarins.

The coastal people had a different lifestyle. Basically they were fishing people and engaged in small trading activities. No wonder the Chinese central government did not pay attention to the arrival of the Portuguese in Macau.

Portuguese attempts to establish trading ties with China's southern metropolis, Canton, faced countless problems. A series of misunderstandings were to make efforts void. As there were no stable trading relations, illegal commerce emerged in several coastal provinces like Kuangtung, Fukien and Chekiang, thanks to the mandarins' hidden support.

Both countries were unhappy with this situation but it lasted until 1554. It was then that the Chinese and Portuguese tried to reach an agreement on Sanchuang Island by means of a small commercial exchange.

Once again, trade was short-lived. The Portuguese realized the situation and built some precarious huts for their trading activities which used to take place from August to November every year. As they would not accept this situation, around 1555 they moved eastward and settled on Lampacau Island.

There was, however, a prosperous future for the Portuguese. They were going towards Macau where prosperity and safety awaited them. Between 1553 and 1554 the Portuguese were still on Sanchuang and Lampacau (2). Therefore it can be said that it is likely that the Portuguese first reached Macau between 1555 and 1557. After that time Macau soon grew from a fishing village to a town of merchants.

Until Leonel de Sousa and the mandarin of Canton reached an agreement, Sino-Portuguese trade was more or less illegal. Trading relations started to improve only after that agreement was reached.

It is an interesting question as to why the Chinese allowed the Portuguese to settle then, when not so long before they were strongly opposed to their settling in China. One reason, it is believed, is that they were allowed to settle because in response to a request by the southern mandarins the Portuguese succeeded in expelling the pirates who were jeopardizing Chinese interests in the region. Thus the Portuguese ensured peace and safety to navigation in the region.

Meanwhile, the Chinese started to understand that they could profit from foreign trade and at the same time they also realised that isolation was not beneficial. China wanted to profit most from foreign trade but was not interested in becoming involved in its negative aspects. Allowing the Portuguese to settle in Macau was therefore a solution to this problem. Macau would then be a neutral area through which China could take advantage of foreign trade without putting its cultural, religious and moral principles at stake.

The circulation and trading monopoly was held by the Portuguese for one hundred and thirty years, from 1555 until 1685. They were the sole owners of the luctrative trade between China, the Philippines, Thailand, Malacca, India and Europe until Emperor Kung-he opened up Chinese trade to the rest of the world.

THE POLITICAL-ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK OF MACAU

The first people to settle in Macau were composed of Portuguese from the motherland, those born in India (known as Mestizos), Christian Chinese with Portuguese blood, pagan Chinese, black slaves, Timorese, Thai, Japanese and Malaysians. The population grew rapidly and soon reached sixteen thousand, two hundred, excluding women and children. We can see, then, the foundations of a government in Macau, when in 1620 Diogo Pereira was elected to the post of 'Capitão da Terra' or 'Land Captain'.

As the government became more complex, more posts were set up. A Justice of the Peace post was set up in 1582 and Matias Penela filled the vacancy. Penela performed his duties in accordance with a 32-clause Regulation issued in Madrid on the 16th February 1587. This regulation was very clear and in Clause 1 it stated: 'He will take note of all civic affairs and crimes' (3).

The ever-growing importance of Macau, in terms of population, trade and wealth called for its upgrading from village to city status. That happened on the 10th of April 1586, pursuant to a charter granted by the Viceroy of India, D. Duarte de Meneses, Count of Tarouca. All its privileges, honours, etc. were similar to those of the city of Évora. Later, a Royal Charter dated 18th April 1596 (4) confirmed these privileges and honours.

On the 24th of January 1603, King Filipe II issued a charter granting Macau the privilege to elect the judge and clerk of the court every three years as happened in the Indian cities. (5)

The city was developing and an ever growing mercantile bourgeoisie was taking over the government through the Senate.

JURIDICAL GROUNDS OF THE PORTUGUESE SETTLEMENT IN MACAU

There are different opinions about the juridical grounds of the Portuguese settlement in Macau. It can, however, be said that Portuguese and foreign historians believe that the Portuguese settlement in Macau was a reward given by the Chinese in exchange for the help the Portuguese gave them in expelling pirates from the South China seas.

In order to have an opinion about the real juridical grounds of the Portuguese settlement in Macau, it would be useful to look into various juridical stances governing foreign ownership of a territory in the light of international law:

- Macau was conquered by the Portuguese and China never agreed to it;

- Macau was given to the Portuguese by the mandarins of Canton, but without the agreement of the Peking Court;

- Macau was given to the Portuguese by both Canton and Peking;

- Macau was given to the Portuguese directly by Peking.

Let us focus on each of the above assumptions.

There is no reason to believe that the first assumption is real. Neither is the second one, since granting territories to foreign powers is not the business of a provincial governor. This must be done by the central government in accordance with the appropriate formalities. As regards the last two assumptions, it can be anticipated that the fourth was not the grounds for the Portuguese settlement in Macau because in a feudal society like that of China, it is unlikely that the Portuguese could ever reach the central government and start direct discussions with an emperor who despised everything that came from abroad. The third assumption is the most probable one and special attention should be paid to it.

Only a joint action following the hierarchy of Chinese society could lead to the granting of Macau to the Portuguese. The Canton authorities - the governor or mandarin and his acolytes - who had full knowledge of the matter, advised and helped Peking to take the final decision.

Although it has yet to be produced, there should be some kind of document granting Macau to the Portuguese. Otherwise, the Portuguese would have been regarded as invaders or trespassers and as such they could have been expelled at any time.

In the light of this, it is believed that such a document, authorizing the Portuguese to settle in Macau existed, but it may have disappeared.

There are two documents in the Ajuda Library which can be of help in clarifying this point:

- The first document states that the Emperor of China granted Macau to the Portuguese in exchange for 'five hundred fine silver taels' (6), after they expelled the pirates from the Canton region;

- The second manuscript states that Macau was granted to the Portuguese by the governors or mandarins of Canton (7).

Some refer to it as a concession. In this case there should be a concessionary document written by the Emperor or the Mandarin of Canton, or both. It is, however, certain that Macau was subject to a concession but it is not known for sure how it materialized. Besides, without a document certifying the concession, the Portuguese would not feel secure. Mandarins changed periodically and every time this happened, the concession would have to be renewed and that would pose many problems.

The settlement of Macau was not a colonial one because settlers were so few when compared with the locals. A concession in exchange for a royalty is also unlikely, otherwise Portugal could not have had full powers over it.

The conditions in which the Portuguese settled in China prior to 1557, when they moved from island to island and settlement to settlement (according to the laws of the country), and after that, when they settled in Macau, are very clearly differentiated.

This matter should be further analysed in order to collect more data which could lead us to clarify some issues:

- In his work entitled Ásia Portuguesa (8), Faria e Sousa states that the concession of Macau was given by the Chinese authorities to the Portuguese as a reward for expelling the pirates from the Canton region;

- Father Juán de la Concepción, in his book L'Histoire Générale des Philippines states the same:. "In recognition of the extraordinary service rendered by the Portuguese (expelling the pirates from the region of Canton) in very serious conditions, the Emperor allowed the Portuguese to settle in Macau on a permanent basis";

- This opinion is further supported by Álvaro Semedo (9). A few more comments supporting this assumption could be added:

- The Italian priest Du Halde, in his work Description de la Chine, supports the same idea;

- The same assumption is backed by Sonnerat, a purser in the French Navy on the Chinese seas (10);

- And even Reynal who is known by his anti-Portuguese sentiments, could not find a different explanation.

However, the above assumptions are now strongly opposed by modern authors. They resent the testimony left by renowned historians and instead they support biased reports by Chinese writers. They base their position on a text from a chronicle of Hianshan island which was translated by Morrison and included in the Chinese Repository.

The renowned French sinologist Abel Rémusat does not agree with the translation of the chronicle made by Morrison because, so he says, he changed substantially the chronicle contents due to preconceptions: According to Abel Rémusat the correct translation should be:

"In the 32nd year of Kin Thsing (1553), foreign ships (Portuguese) anchored at Hao-King. Those who disembarked said that they had been caught in a storm and the sea had soaked all the goods that they had taken as tributes. Therefore, they wanted to dry them on Hao-King beach. Wong-pe, the commander in charge of the area, allowed them to do this.

They built only some huts. However, as the merchants wanted to do business, little by little they started to build brick, wooden and stone houses. This was how the foreigners (Portuguese) managed to enter the empire illegally. They started to settle in Macau in the Wong-pe period (11)".

To support their position the modern authors argue that: -

The Government of Macau paid the Chinese government a rent or charge for a long period of time;

The mandarins often interfered in Macau's government;

The Chinese government had a customs house in Macau to charge duties on ships and goods.

However, in the light of international law these situations are known as 'International Easement' which does not make void the concession, but limits the sovereignty instead. However, in order to go deeper into this subject, we must collect some more information.

From a Chinese point of view, Macau could have been given away as a result of the liberalism of the mandarins of Canton, with the approval of the Emperor, or as a concession subject to a rent or charge. As regards the first assumption it may give ownership rights to the party to whom the territory was granted. On the other hand, the second assumption is very doubtful because if a rent is paid it means the tenant does not own the territory subject to concession. Going back to the first assumption, it can also be said that ownership may be cancelled as soon as the party who granted it so wishes. These unclear situations help us to understand why the Macau authorities were dependant upon the mandarins.

It should be also noted that China had been closed from international circles for centuries and therefore international law regulations on the acquisition of territories did not apply to it.

After China decided to be part of the International Community (1858 and 1860) (12), it would be pertinent to discuss the forms of territorial ownership and sovereignty in the light of international law: cession, conquest, long-term occupation and prescription.

It would be useful to analyse each one of them in order to have a better understanding. If we are to believe that the concession of Macau was made after the Portuguese expelled the pirates from the South China seas, then it was a cession even though the relevant document is yet to be found. In addition, if the Portuguese were not sure of their rights over Macau, they would have acted differently. On the other hand, if the Chinese did not have the same thought, they would not have let the Portuguese stay on a permanent basis.

As regards the conquest, it is hard to accept it because the Portuguese expelled the pirates from the South China seas and Macau with help from the Chinese.

Long-term occupation is yet another form of ownership. When a foreign country occupies a territory for a long period of time, that foreign country gains the right to own it providing the following occurs:-

- The territory does not belong to anybody or has been abandoned;

- Occupants intend to stay indefinitely in the territory.

Besides, Lisbon did not give the first Portuguese settlers in Macau permission to conquer it. Therefore, it could not be called a conquest, but a peaceful occupation instead. China has never complained about the Portuguese presence in Macau although it would have been very easy to do so.

Another sign that China accepted the Portuguese is that when they opened Canton and other ports to European trade they did not let them stay there on a permanent basis. Besides, with the construction of a wall on the strait linking the peninsula to the mainland, China accepted that Macau was independent from it.

Portuguese sovereignty gained public recognition when European nations sought Lisbon's permission to set up their consulates in Macau.

RESTRICTIONS ON THE PORTUGUESE SOVEREIGNTY OF MACAU

Some facts that we mentioned earlier are very often used to refute the Portuguese sovereignty of Macau, such as:-

- the payment of a rent or charge to the Chinese authorities;

- the actual power that the mandarins of Canton had over Macau which was translated into jurisdictional acts;

- the setting up of a secondary mandarinate to resolve matters involving Chinese people;

- the collection by the Chinese of duties on goods and ships in Macau;

- the Chinese attempt to force the royal galleons to pay tonnage duties because they argued that those were freighters rather than war ships;

- the embargo on a Portuguese armada in Macau, in 1637, as the Chinese alleged that one of its ships was bigger than the legal size;

- the fact that all Portuguese nationals had to use their passport whenever they wanted to leave the city;

- the Portuguese had to conform to some of the Chinese laws, and an example of that was the mourning on the death of Emperor Kung-he's mother.

Although all these facts must be taken into consideration, they were not important enough to invalidate the sovereignty in general.

The privileges and favours enjoyed by the Portuguese when compared to other foreign people, namely in terms of navigation and trade, made Macau a unique trading gateway between China and Western countries. The mandarins then became jealous of the wealth generated in Macau, and imposed all sorts of measures to exploit the Macau merchants. In order to put those merchants under pressure the mandarins prohibited the Chinese from supplying food and rendering services.

Some facts give grounds to what we described above: the governor of Kwantung Province was against the setting up of a court and of administering justice by the Portuguese. He argued that when the Portuguese were authorized to settle in Macau those matters had not been discussed. However, as the Macau Senate offered him some money, the governor calmed down.

As the territory's wealth grew, the mandarins imposed more demands and attempts to make Macau more dependent on them were also growing. The territory's fate was in their hands because many things depended on the Chinese; they supplied caulkers, masons, tailors, blacksmiths and food. Once Macau lacked these resources it would be an easy prey for the mandarins.

Those adverse conditions made void all forms of ownership recognized by both the international community and China. The only solution for the mandarins was to wait for a better tomorrow.

The Senate met many times to try to meet the mandarins' demands. There was no other solution but 'to accept or die'.

CONCLUSION

We have focused on the most significant episodes in the history of a small territory and also some episodes which date back to the early years of the 16th century when some Portuguese ventured to the East. Those men were unfolding the history of Portugal.

In fact, compared to the other Portuguese colonies, the history of Macau is more difficult to tell because two very different civilizations crossed each other. This generated conflicts which called for mutual understanding throughout the years in order to achieve a peaceful environment between the two people. Despite all developments, the pattern of life in Macau is not very different to that in China. It was impossible to resist the weight of the Chinese influence.

The story of Macau/Portugal is coming to an end. The last outpost of the Portuguese Empire is going to disappear. And what of Macau's future? We foresee a peaceful and prosperous future.

PRINTED SOURCES

BOXER, C. R., notes and comments - A cidade de Macau e a queda da Dinastia Ming. Macau, Escola Tipgráfica do Orfanato, 1938.

BOXER, C. R., comp. - Macau na época da Restauração. Macau, Imprensa Nacional, 1942.

BRAGA, J. M., notes - O primeiro acordo lusochinês: realizado por Leonel de Sousa em 1554. Macau 1938.

CORTESÃO, Armando - A propósito do ilustre boticário quinhentista Tomé Pires. Coimbra, 1964.

FREITAS, Jordão de - Macau: materiais para a sua história no séc. XVI. Macau, Instituto Cultural, 1988.

Memoire sur la souveraineté territoriale du Portugal à Macau. Lisbon, Imprensa Nacional, 1882.

REGO, António da Silva - 'A presença de Portugal em Macau. Lisbon, Agência Geral das Colónias, 1946.

Translated by José Vieira

REMARKS

(1) The ostentation of the Chinese emperors can be seen in the reply that Quienlong gave to the English emissary, Macartney in the 18th century: "We order the King of England to take into consideration our remarks. Your envoy knelt down in front of our throne. With benevolence, we read your message and we were happy to learn that you are respectfully humble. However, your request for your subjects to live on a permanent basis in Peking and trade in my ports is unacceptable because it goes against the unchangeable uses of my court", in Alain Peyrefitte, 'Choc des cultures entre communautés', Revue des Sciences morales et politiques, p. 107.

(2) Letter written by Fernão Mendes Pinto on 20th of November, 1555, in Arquivo Histórico Português, VIII, pp. 213/214, and in Fernão Mendes Pinto, by Cristóvão Ayres, pp. 78/82, quoted by Charles Boxer in Descrição de Macau, p. 16.

(3) Overseas Historical Archives - Macau, sundry documents, box 1, doc. no. 1.

(4) Macau Historical Archives - Film Library, Cabinet I, Drawer I (Foral de Macau).

(5) Overseas Historical Archives - Macau, sundry documents, box 1, doc. no. 2.

(6) Ajuda Library 51 - VIII - 40, pp. 232/234: "Relação do Princípio que teve a cidade de Macau e como se sustentou até ao presente", quoted by A. da Silva Rego in A presença de Portugal em Macau (Lisbon, A. G. C., 1946).

(7) Ajuda Library 49-V-5, folio 348.

(8) Book III, part III, chapter XXI.

(9)Relação da China, part II, chapter I,1643 edition.

(10)Voyage aux Indes Orientales et à la Chine, book II, page 7, quoted in Memoire sur la souveraineté territorial du Portugal à Macau.

(11)Memoire sur la souveraineté territorial du Portugal à Macau, page 18.

(12) Peyrefitte, Alain, in 'Choc des cultures entre communnautés: les Occidentaux en Chine, XVIII et XIX siècles', page 112: "It was during the war that England and France fought against China between 1858 and 1860, that the latter came to recognize the principle of equality of countries."

* Graduate in Social and Political Sciences, Theology, Philosophy and Documentary Sciences. Currently heads Macau's Historical Archives.

start p. 3

end p.